Where does the gang originate?

MS-13’s home base is in El Salvador.

Experts say the violent culture of the gang comes out of the at-times lawlessness of the country, where police and the army and street gangs in poorer neighborhoods have waged fights for control with almost no holds barred.

When did they show up on Long Island and where have they spread?

For the most part, MS-13 gang members who come to the United States settle in areas where there are already Salvadoran communities — on Long Island in Brentwood, Central Islip, Huntington Station, Hempstead and Freeport.

The street gang has existed for decades, but the recent uptick in activity on Long Island has been linked by officials to the surge in immigrant teens who have come into the country as unaccompanied minors since 2015. Suffolk County ranks near the top in the nation for the number of children who cross the border illegally, according to recent statistics. The gang sees them as potential recruits.

Officials stressed that not all unaccompanied minors are gang members.

How many members are there on Long Island?

Authorities in Nassau County have identified close to 500 MS-13 members, 300 of whom are still active, police said.

Suffolk County currently has about 300 confirmed members of the gang, along with another 200 associates identified, police said.

How many have been charged with crimes?

The situation is fluid. In January, 17 MS-13 members were arraigned in Nassau County and charged in connection with crimes that ranged from murder and drug trafficking to conspiracy and weapons possession. Swept up in the 21-count indictment was Miguel Angel Corea Diaz, the man who Nassau County District Attorney Madeline Singas identified as the leader of East Coast operations for the gang.

Suffolk police have made 330 arrests of 220 individuals since the Brentwood murders of two teenage girls in September 2016, according to District Attorney Timothy Sini, the county’s police commissioner until early January.

How has the gang evolved?

Experts believe the recent eruption of gang violence on Long Island is due to a new and more deadly profile of MS-13. At the heart of that profile are newcomers from Central America eager to make their mark within an immigrant gang already known for its code of brutality and violence and its weapon of choice, the machete.

These newcomers have found a niche in MS-13 on Long Island — replacing those who have been arrested — and are focused on proving themselves to be even more violent than established gang members.

Experts say MS-13 members commit violence for its own sake, in large part as a way to carve out and control the turf they consider theirs, purging it of rival gang members and others perceived as having disrespected MS-13.

What is the profile of an MS-13 gang member?

Increasingly, new recruits to the gang are young.

The machete is their principal weapon, in part because of its savagery, but also because it is commonly available and used for agriculture in Central America, authorities say. It is cheaper to purchase both there and in the United States, where guns are harder to obtain and more expensive, several experts say.

How do they make money?

A member of MS-13 usually puts in an eight-hour day at a low-paying job, sources say — but then is required to go out at night and “put in work,” or hunt down perceived enemies.

Recently arrested members of the gang have been employed as restaurant workers, car washers, landscapers, salad makers and sheet-metal platers, sources said.

But the gang cannot survive without money, Homeland Security Special Agent in Charge Angel M. Melendez said. The gang has a “sophisticated financial network that supports nefarious activities” through prostitution, extortion and collection of dues.

Who does MS-13 target?

The gang is thought to target perceived rivals in immigrant communities. They can either be those perceived to have disrespected the gang, rival gang members, witnesses to crimes and anyone believed to cooperate with law enforcement, Nassau District Attorney Madeline Singas has said.

Most of the victims on Long Island have been young Latinos and blacks, many of school age, authorities say.

Who have their victims been so far?

MS-13 is responsible for 25 fatalities since January 2016, according to Suffolk and Nassau police.

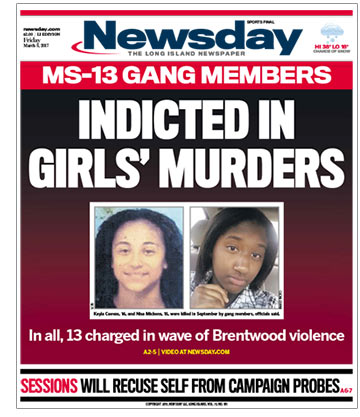

The brutal beating deaths of two teenage girls in Brentwood in September 2016 shone a light on the violent nature of MS-13.

Kayla Cuevas, 16, was “involved in a series of disputes” in person and over social media with MS-13 members and associates in the months before the killings, prosecutors said in court papers. She and her best friend, Nisa Mickens, 15, were killed by four MS-13 gang members who had gone “hunting for rival gang members to kill” when they came across Cuevas and Mickens, court papers said.

At least one recent victim, Jose Pena, 18, was a member of the gang. He was suspected of being an informant.

In January 2017, the body of Julio Cesar Gonzales-Espantzay, 19, of Valley Stream, was found in the Massapequa Preserve stabbed with machetes and shot, according to court records.

In April 2017, a quadruple homicide in Central Islip was linked to the gang. The victims were Justin Llivicura, 16, of East Patchogue; Jorge Tigre, 18, of Bellport; Michael Lopez Banegas, 20, of Brentwood; and his cousin, Jefferson Villalobos, 18, of Pompano Beach, Florida, who had arrived on Long Island for a visit just days earlier.

The four were targeted by MS-13 because they had disrespected the gang and belonged to a rival organization, according to court documents. But only one of the four victims was friendly with MS-13 members and associates and was the main target, Suffolk police officials said.

The body of Angel Soler, 16, of Roosevelt, was found Oct. 19 in woods in the Roosevelt-Baldwin area. Federal and local investigators believe Soler was killed by MS-13 members, according to sources.

The remains of Kerin Pineda, 20, were found in thick woods near the Merrick-Freeport border and the remains of Javier Castillo, 16, of Central Islip, were found in Cow Meadow Park and Preserve in Freeport, also in October, authorities said. The FBI identified the remains of two men in November, officials said.

What can be done to curb the gang?

The gang has been identified as a top priority for the FBI.

Officials have said gathering intelligence is key to the effort. But prevention is also critical including in schools, and officials are focusing on that as well.

Suffolk police, the FBI and other law enforcement agencies have responded to suspected gang killings by beefing up their presence in Central Islip, Brentwood and other Long Island communities where MS-13 is active, since the quadruple homicide in April. State and county leaders, meanwhile, have poured millions of dollars into social services and gang-intervention programs aimed at eliminating MS-13’s most important asset, its recruits.

The 2019 budget approved by state lawmakers includes $16 million for social service programs to combat gangs in Nassau and Suffolk, including $3 million to Catholic Charities for case management of unaccompanied immigrant children who move to Long Island and are vulnerable to MS-13 recruitment.

Where else in the country is MS-13 a problem?

MS-13 has 10,000 members in at least 40 states, according to Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who spoke about the gang on Long Island in April 2017.

What do you think about legalizing pot in New York?

Support for decriminalizing marijuana and making it available for sale in New York is gaining political momentum.

What are your views on legalizing pot?

Submit your responseThank you for your submission. Check back soon to see if it was posted.

NEWSLETTER SIGNUP TEST

How well do you know the Fire Island ferry?

Each year, hundreds of thousands of passengers rely on the Fire Island ferry to carry them from Long Island’s South Shore to Fire Island’s beaches.

Since 1948, the Fire Island Ferries company has seen changes in ownership, rough seas and a controversy or two, but the motors start each day, ready to travel across the Great South Bay as the largest of three of Long Island’s long-standing ferry providers.

In interviews, the company’s owners and employees shared their memories of the 70 years that transformed the ferry from ragtag salvage boats running from Bay Shore to Ocean Beach to a modern fleet that serves eight Fire Island communities.

Watch the videos below to find out more about the ferry’s past and test your Fire Island knowledge with reporters Laura Blasey and Rachelle Blidner and Fire Island Ferries president Timothy Mooney.

How did the ferry get started?

In 1947, founders Elmer Patterson, Bill White and Ed Davis won a bid to operate the Ocean Beach ferry terminal because the original ferry operator failed to submit one after 25 years in business, company officials said. Watch Laura Blasey explain.

What kinds of boats made up the first fleet?

Founder Elmer Patterson scrambled to put a fleet together. Among the vessels he salvaged were Prohibition-era rum runners, upgraded with surplus engines from the military. Watch Timothy Mooney describe the fleet.

How did the original fleet operate?

The ferry originally didn’t have a schedule. The boats continually made trips between shores, but sometimes service was canceled abruptly because the boats lacked equipment to navigate in foggy or icy weather, ferry officials said. Rachelle Blidner shares the ferry’s past.

Did any of the ferries sink?

Fire Island Ferries is proud of its record of never having to abandon ship, but it came close in 1976, when the Fire Island Queen got stuck on a sandbar in the Captree channel, according to Edwin Mooney Jr.’s book, “Ferries to Fire Island: 1856-2003.” Rachelle Blidner explains.

How did the Fire Island Ferries expand?

For the May 1, 1948 maiden voyage, there was only one destination: Ocean Beach. Today, the company carries passengers to eight Fire Island communities. Watch Timothy Mooney share more.

Which celebrities have been spotted onboard?

Even for celebrities, the ferry was the preferred way to travel to Fire Island. Famous faces aboard the boats included Marilyn Monroe, Liz Claiborne, Martin Luther King Jr., Milton Berle, Ethel Merman and Joseph Heller, ferry officials said. Laura Blasey explains.

How did the company find enough parking as they expanded?

Open space along the Great South Bay is hard to find. The founders had to create their own by dredging and filling a channel on unused swampland before the current Bay Shore terminal opened in 1952, Timothy Mooney said. Rachelle Blidner has the answer.

What name were unruly passengers given last year?

When company officials canceled the 1 a.m. boat from Ocean Beach in 2017, they placed the blame on drunken customers in a company Facebook post. The passengers got into fights and increased security costs, the company said. Watch Rachelle Blidner explain.

What’s the “death boat”?

When the weekend ends, so does the vacation for 9-to-5 workers. The first ferry back to Bay Shore left at 5:50 a.m. in the summer, earning it the nickname “death boat” from ferry employees, Edwin Mooney Jr. said. Watch Laura Blasey explain.

Nassau crime by category in early 2018

Most major crimes were down in the first 11 weeks of 2018 in Nassau County, but there were increases in rape, commercial robbery and grand larceny, according to data provided by the Nassau County Police Department.

As a group, major crimes were down 0.33 percent, but lesser crimes were up 1.32 percent, bringing the total number of crimes reported in Nassau to 7,594, up 0.98 percent from the 7,520 crimes reported in 2017. The period measured goes from January 1 to April 23 in each year. Posted on April 24, 2018

Murder and sex crimes

Murders dropped from three down to one, but rape went from zero to three. There were nine crime in these four categories in 2018.

- 2018

- 2017

Other major crimes

Many more crimes in these categories, so note the change in scale compared to the first chart.

You can read more here. JavaScript charts via amCharts.com.

The numbers

| Crime | 2017 | 2018 | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murder | 3 | 1 | -66.67 |

| Rape | 0 | 3 | – |

| Criminal sexual act | 3 | 3 | 0.00 |

| Sexual abuse | 5 | 2 | -60.00 |

| Robbery, commercial | 43 | 52 | 20.93 |

| Robbery, other | 74 | 65 | -12.16 |

| Assault, felony | 112 | 109 | -2.68 |

| Assault, misdemeanor | 202 | 183 | -9.41 |

| Burglary, residence | 148 | 118 | -20.27 |

| Burglary, other | 110 | 87 | -20.91 |

| Stolen vehicles | 127 | 118 | -7.09 |

| Grand larceny | 900 | 962 | 6.89 |

| Total major crimes | 1,525 | 1,520 | -0.33 |

| All other crime reports | 5,995 | 6,074 | 1.32 |

| Total crime reports | 7,520 | 7,594 | 0.98 |

LI’s March unemployment rates

The overall unemployment rate on Long Island for March 2018 rose to 4.6 percent, 0.4 percentage points above where it was in March 2017, according to data from the state’s Department of Labor.

Southampton Town had the highest rate, 7 percent (up 0.7 points), and the Town of Riverhead had the biggest increase, going up 0.9 points to 6.5 percent. In Nassau, Hempstead Village had the highest rate, up 0.5 points to 6.7 percent. Click on the bar chart for details, or check on the tables below. Posted April 24, 2018.

The jobless rates in Long Island towns and villages

Details on the local unemployment rates

| March 2018 | Labor Force | Employed | Unemployed | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nassau-Suffolk | 1,464,100 | 1,397,300 | 66,800 | 4.6 |

| Nassau County | 694,700 | 665,200 | 29,500 | 4.2 |

| Freeport Village | 22,600 | 21,300 | 1,300 | 5.6 |

| Glen Cove City | 14,100 | 13,300 | 700 | 5.2 |

| Hempstead Town | 395,800 | 378,200 | 17,600 | 4.4 |

| Hempstead Village | 27,700 | 25,800 | 1,800 | 6.7 |

| Long Beach City | 19,500 | 18,700 | 800 | 3.9 |

| North Hempstead Town | 112,200 | 107,800 | 4,500 | 4.0 |

| Oyster Bay Town | 153,100 | 147,200 | 5,900 | 3.8 |

| Rockville Centre Village | 12,100 | 11,700 | 500 | 3.8 |

| Valley Stream Village | 19,400 | 18,500 | 900 | 4.5 |

| Suffolk County | 769,400 | 732,100 | 37,300 | 4.9 |

| Babylon Town | 110,000 | 104,700 | 5,300 | 4.8 |

| Brookhaven Town | 251,000 | 239,300 | 11,700 | 4.7 |

| Huntington Town | 103,100 | 98,700 | 4,400 | 4.3 |

| Islip Town | 176,400 | 168,100 | 8,300 | 4.7 |

| Lindenhurst Village | 15,000 | 14,400 | 600 | 3.9 |

| Riverhead Town | 16,100 | 15,100 | 1,100 | 6.5 |

| Smithtown Town | 59,000 | 56,700 | 2,300 | 3.9 |

| Southampton Town | 29,500 | 27,400 | 2,100 | 7.0 |

| New York City | 4,246,000 | 4,068,100 | 177,900 | 4.2 |

| New York State | 9,633,500 | 9,175,100 | 458,400 | 4.8 |

| Feb. 2018 | Labor Force | Employed | Unemployed | Rate (%) |

| Nassau-Suffolk | 1,459,700 | 1,385,600 | 74,100 | 5.1 |

| Nassau County | 691,800 | 659,300 | 32,500 | 4.7 |

| Freeport Village | 22,500 | 21,100 | 1,400 | 6.0 |

| Glen Cove City | 14,000 | 13,200 | 800 | 5.9 |

| Hempstead Town | 394,000 | 374,800 | 19,200 | 4.9 |

| Hempstead Village | 27,600 | 25,600 | 2,000 | 7.2 |

| Long Beach City | 19,400 | 18,600 | 800 | 4.1 |

| North Hempstead Town | 111,800 | 106,800 | 5,000 | 4.5 |

| Oyster Bay Town | 152,600 | 145,900 | 6,700 | 4.4 |

| Rockville Centre Village | 12,100 | 11,600 | 500 | 4.1 |

| Valley Stream Village | 19,200 | 18,300 | 900 | 4.7 |

| Suffolk County | 767,900 | 726,300 | 41,600 | 5.4 |

| Babylon Town | 109,700 | 103,900 | 5,900 | 5.4 |

| Brookhaven Town | 250,500 | 237,400 | 13,100 | 5.2 |

| Huntington Town | 102,800 | 97,900 | 4,900 | 4.8 |

| Islip Town | 176,000 | 166,800 | 9,200 | 5.2 |

| Lindenhurst Village | 14,900 | 14,300 | 700 | 4.4 |

| Riverhead Town | 16,100 | 15,000 | 1,200 | 7.3 |

| Smithtown Town | 58,900 | 56,300 | 2,600 | 4.4 |

| Southampton Town | 29,400 | 27,200 | 2,300 | 7.7 |

| New York City | 4,273,900 | 4,088,300 | 185,600 | 4.3 |

| New York State | 9,676,200 | 9,180,900 | 495,300 | 5.1 |

| March 2017 | Labor Force | Employed | Unemployed | Rate (%) |

| Nassau-Suffolk | 1,482,600 | 1,419,700 | 62,900 | 4.2 |

| Nassau County | 703,600 | 676,000 | 27,600 | 3.9 |

| Freeport Village | 22,900 | 21,700 | 1,300 | 5.6 |

| Glen Cove City | 14,200 | 13,500 | 700 | 4.9 |

| Hempstead Town | 400,900 | 384,300 | 16,600 | 4.1 |

| Hempstead Village | 28,000 | 26,200 | 1,700 | 6.2 |

| Long Beach City | 19,800 | 19,000 | 700 | 3.6 |

| North Hempstead Town | 113,600 | 109,500 | 4,100 | 3.6 |

| Oyster Bay Town | 155,100 | 149,600 | 5,500 | 3.6 |

| Rockville Centre Village | 12,300 | 11,900 | 400 | 3.6 |

| Valley Stream Village | 19,600 | 18,800 | 800 | 4.0 |

| Suffolk County | 779,000 | 743,700 | 35,200 | 4.5 |

| Babylon Town | 111,500 | 106,400 | 5,100 | 4.6 |

| Brookhaven Town | 254,100 | 243,100 | 11,000 | 4.3 |

| Huntington Town | 104,500 | 100,200 | 4,200 | 4.0 |

| Islip Town | 178,700 | 170,800 | 8,000 | 4.5 |

| Lindenhurst Village | 15,300 | 14,600 | 600 | 4.2 |

| Riverhead Town | 16,200 | 15,300 | 900 | 5.6 |

| Smithtown Town | 59,800 | 57,600 | 2,100 | 3.6 |

| Southampton Town | 29,700 | 27,800 | 1,900 | 6.3 |

| New York City | 4,240,500 | 4,052,500 | 188,000 | 4.4 |

| New York State | 9,711,000 | 9,258,000 | 453,000 | 4.7 |

Kickstarter projects on Long Island

As of May 2, there have been 641 Kickstarter projects based on, or dealing with, Long Island, according to data posted on the crowdfunding site. Roughly one in four of them succeeded in reaching its stated goal, which amounted to more than $984,000. The rest of the projects, seeking a combined total of more than $33 million, were canceled, suspended or designated as a failure. There are three Long Island projects that were ongoing as of May 2.

The two charts below show the number of successful and failed or canceled projects, as well as the total of all the goals set in each category. This was posted on May 3, 2018.

How the 641 Long Island projects worked out

About 27 percent met their stated money goals. The rest were called off or failed.

How those 641 LI projects broke down by goal amounts

The 173 successful projects were aiming to raise less than 3 percent of all the LI money goals.

Top dozen successful LI projects

The biggest goals that were achieved. Some projects surpassed their stated goal.

A new Erick Sermon album: I’m launching a new label with an album featuring Method Man, Pharrell Williams, Big K.R.I.T, Styles P, and Redman among others. Goal: $60,000

Lithology Brewing Co. Campaign to Expand Beer Production: Award Winning Lithology Brewing is expanding production of our innovative craft beer. Be a part of it! Goal: $35,000

The Gathering: Reuniting Pioneering Artists of Magic: Rediscover over 35 of the original artists of Magic: The Gathering reunited to create new paintings for this limited release art book. Goal: $32,000

Condzella Hops Unites L.I. Farmers and Local Breweries: Long Island Farmer Imports a German Hops Harvesting Machine for Cooperative Use with Local Hop Farms to Support Local Breweries. Goal: $27,000

Moustache Brewing Co.- We’re growing a moustache!: A small craft brewery serving Long Island and NYC. We are passionate about creating, sharing and educating people about craft beer. Goal: $25,000

Undocumented: The Life Story of Dr. Harold Fernandez: The true story of a cardiac surgeon who came to the U.S. as a young undocumented immigrant. An American tale of struggle and triumph. Goal: $25,000

Help Get the Wheels Rolling for the Elegant Eats Food Truck: Funding is needed so the Elegant Eats Food Truck can start serving healthy flavorful meals across Long Island, NY. Goal: $22,500

A New Album by Bryce Larsen: I am really happy with the way that I relate to music right now and I want to capture this fleeting moment in an album, the right way. Goal: $20,000

Destination Unknown Beer Company: DUB CO is excited to add to the already amazing craft beer movement hitting Long Island. With your help we can increase our production! Goal: $20,000

Join The Walking Tree in Releasing Their First Full Record!: Partner with The Walking Tree to raise $18,000 in 30 days! We need your help in releasing this record for free through Come&Live! Goal: $18,000

The Brick Studio: The Brick Studio is a forming 501(c)(3) nonprofit art collective organization located in Rocky Point, N.Y. Help us to get started! Goal: $18,000

Hua Mulan–A Bilingual EBook: A Bilingual EBook Version of a Classic Chinese Story with Audio in English and Chinese Goal: $17,000

You can read more about crowdfunding on Long Island.

Suffolk’s plan to clean its waterways could cost about $20,000 per household — and that’s just one hurdle

Suffolk County has launched an ambitious plan to clean the region’s waters by getting homeowners to abandon cesspools and septic systems in favor of advanced and more costly treatment technology, but the effort is hitting technical and political hurdles, a review by Newsday/News 12 has found.

County-ordered tests show that only one of the four advanced systems approved by Suffolk in 2016 and 2017 has routinely met the threshold county officials set for reducing nitrogen, a key contributor to the polluting of Long Island’s waterways.

A fifth system, approved this year, also met the standard, although in a single round of the ongoing testing, county officials said.

Additionally, county officials have encountered resistance from legislators who say they fear a voter backlash over the increased per-household cost of improving wastewater treatment.

“Alternative on-site wastewater treatment” systems — in essence, mini sewage-treatment plants that would be placed in thousands of yards across Suffolk County — are more effective than traditional cesspools and septics but, at an average of just under $20,000, are also at least twice as costly and require more maintenance.

What’s in the water? Flush with questions

Watch “Flush with Questions,” a News 12/Newsday exclusive report, Thursday on News 12 Long Island — as local as local news gets.

“Clearly we want to see the whole universe of these performing better,” Walter Dawydiak, Suffolk’s director of the Division of Environmental Quality, said during a February conference call with environmentalists, builders, officials and others involved in the effort.

But he emphasized that the results were still encouraging

“Even the worst of these systems is showing 50 percent removal [of nitrogen],” he said later.

Most homes and businesses in the counties surrounding New York City, including Nassau, are connected to sewer systems. Nearly 75 percent of Suffolk homes, though, do not have sewer service. Suffolk officials estimated that some 252,000 cesspools — holding tanks that eventually leech untreated waste directly into the ground — are in place in the county. An additional 108,000 properties are served by traditional septic systems, which offer better overall treatment but do little to reduce nitrogen.

That decades-long legacy of nitrogen-rich waste moving from homes largely unfiltered to the ecosystem has in part led to harmful algal blooms, loss of shellfish stocks, degraded wetlands and lower oxygen levels in Long Island’s surface waters, including its bays, rivers and Long Island Sound.

Individual systems

Nearly 75 percent of Suffolk County relies on cesspools and septic systems to treat its waste. Officials say the nitrogen from those systems is degrading water quality. Here’s a look at what is in use now and the advanced technology the county is pushing. Dollar figures are the initial costs of each system.

Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone labeled nitrogen as “public water enemy No. 1” in 2015 and released a wide-ranging water-resources management plan to reverse declining water quality, which included the advanced systems. That same year, the county started a pilot demonstration program to test some of these systems, selecting homeowners via lottery to get equipment installed at no cost.

In 2016 Bellone and the legislature amended the county sanitary code, outlining how the advanced systems would be tested, and setting rules for the average amount of nitrogen the new technology could release before being approved for widespread use.

Suffolk officials settled on 19 milligrams of nitrogen per liter, limits also used in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, where officials have been battling for more than 20 years to reduce nitrogen levels in wastewater. That level of nitrogen is less than a third of what is usually found in raw sewage, but also nearly twice the state’s standard for what can be released by a large municipal sewage-treatment plant — the type to which sewer pipes are connected.

Supporters hailed the change, saying it had been a long time coming and necessary. They noted that for more than 50 years it’s been known that disposing of waste into groundwater is not wise for the environmental and economic well-being of an island where tourism and recreation are big business.

“This is as big or bigger than any other major policy issue that the Island has confronted,” said Kevin McDonald, conservation project director for public lands at The Nature Conservancy on Long Island. “Any of these systems on their worst day can’t be worse than what we have now,” he added. “Even if they only perform at 50 percent that’s better than what we’re doing now.”

Bellone declined to be interviewed, instead referring questions about the Newsday/News 12 review to Deputy County Executive Peter Scully.

The county’s so-called water czar, Scully said manufacturers will be given a chance to make adjustments to make their systems more effective, but over the long-term, if they can’t meet the standard they won’t be approved for general use in Suffolk County.

“It’s very early in the process and the dataset is small but the county is forcing the manufacturers to meet a standard that is very difficult to meet,” he said. “But the standard is in place for a reason.”

As the county studies how the technologies perform, five systems that made it through the first round of testing are provisionally approved for sale. Read the rest of the story.

Where is the money for these systems coming from? Grants and loan programs are available to help with the added expense, but that money is limited.

Expense is a major concern when it comes to the advanced wastewater treatment systems that are a big part of Suffolk County’s program to reduce nitrogen heading from homes to waterways and drinking aquifers.

The units cost two to four times more than a conventional wastewater system to install and hundreds of dollars extra each year to operate and maintain.

County and state governments have set up grants to offset about half the initial costs, and made loans available to cover the other half. East End towns, funded by town-approved taxes on real estate transactions, have their own grant programs.

That money is limited, though, and additional funding sources will have to be found; the money set aside so far will cover only a couple thousand of the systems in a county where an estimated 252,000 properties still rely on low-tech cesspools.

The added costs

Suffolk County officials say average installation costs of the innovative and advanced systems run $19,200. Builders, installers and engineers said the price tag can be as high as $25,000 to $30,000 for some houses where soil composition and other site conditions might make the work difficult.

That’s compared to about $5,000 to $10,000 to install a traditional septic tank and cesspool, installers said, and as little as $2,000 for a cesspool alone.

In addition to upfront costs and maintenance, the advanced systems also have electrical components that add to utility bills.

In general, the first three years of maintenance costs are included by manufacturers in the installation price. But after that, residents will be required to have an annual contract that will cost between $250 to $300 a year, according to the county.

“If you want to optimize your performance you have to take care of it,” said Justin Jobin, environmental projects coordinator in the Suffolk County health department.

Operators in other states where the systems are already in place say costs can run significant higher.

Annual maintenance contracts range between $500 and $2,000 at Cape Cod, Massachusetts-based Bennett Environmental Associates Inc., according to Samantha Farrenkopf, wastewater program manager for the company, which maintains systems for homeowners and files necessary compliance documents. Joe Martins, owner of Accu Sepcheck in Cape Cod, said contracts are between $500 and $1,800 a year.

The pumps, blowers, air compressors and other equipment use electricity — from $57 to $266 per year, depending on the model, the system manufacturers have told Suffolk officials.

Those parts can also break, and replacements can cost from $11 for a Fiberglas air blower to thousands of dollars for some components, according to out-of-state operators.

Homeowners can kill off the microorganisms that play a key role in nitrogen reduction in the systems by using excessive bleach or flushing chemotherapy drugs, for example. Jobin said systems typically rebound on their own and pumpouts aren’t normally needed.

Under the rules established by county officials, once the systems receive final approval, they will have to be tested every three years for water quality, which will cost about $200, according to local installers. Suffolk officials said that they believed the price for testing, which they said was closer to $100, is included in the price of the operations and maintenance agreement.

Not all systems have the same demands, maintenance needs or costs. A Fuji Clean USA system, which was approved by the county in January, has barely any moving parts and uses technology developed in Japan in the 1960s.

Where is the money coming from?

For installation, purchase and other upfront costs, the county will provide $10,000 to $11,000 for about 1,000 homeowners who receive grants — up to $10 million over five years.

New York State has also allocated $10 million to help the county expand its grant program and pay for up to half the costs of a system. East Hampton, Southampton and Shelter Island are also offering grants of up to $16,000 for residents who qualify based on need, funded from town-approved taxes on real estate transactions.

Mitchell Pally, CEO of the Long Island Builders Institute, a home-builders industry group, said given the increased costs of the advanced systems, homeowners — especially those of modest means — will need help.

“You need the subsidy to make it palatable to people, especially if you’re going to require them to do it,” he said.

How to fund that subsidy in a sustained way is likely to be the subject of policy debates among officials leery of adding to the burden of property owners.

County Executive Steve Bellone in 2016 proposed asking voters to institute a fee on water usage, which would have cost an average family between $73 and $126 a year, to help fund water-improvement projects including advanced systems and sewers. The idea was quashed when state lawmakers in both parties worried the money could be diverted and said they weren’t consulted until shortly before the executive’s administration announced its plan.

County officials, environmental advocates and business groups are discussing the creation of a Suffolk-wide district to administer and fund water-quality programs, including advanced systems and sewers. How it would collect money is to be determined, Scully said.

Proponents of the systems say they expect the costs per unit to go down as more of the units get approved for sale in the county, more installers get certified and engineers get accustomed to putting them in the ground.

“Why wouldn’t this market behave like any other market, that went from emerging to infant to very mature?” said Kevin McDonald, policy and finance adviser to the Long Island branch of The Nature Conservancy, an environmental conservation group.

The East End is already embracing the new septic technology. Local officials say the move shows the county and residents that clean water is a priority.

Officials on Long Island’s East End are moving aggressively to require the installation of advanced nitrogen-reducing septic systems, even as Suffolk County assesses the effectiveness of the technology in cleaning the region’s surface waters.

The Town of East Hampton began in January of this year mandating that advanced systems be installed in all new residential and commercial construction sites or where an existing structure is undergoing an expansion of at least 50 percent.

Southampton is requiring them to be installed in new residential construction or expansions of existing homes in designated areas near bays and streams. Farther to the west, Brookhaven Town has a similar rule, although one limited solely to new construction.

The Shelter Island Town board in May will discuss a proposal to require the advanced systems in construction of all new homes larger than 1,500 square feet.

Advanced on-site wastewater treatment systems are key to Suffolk County’s ambitious plan to reduce the nitrogen pollution that leads to harmful algal blooms, loss of shellfish stocks, degraded wetlands and lower oxygen levels in Long Island’s bays, rivers and Long Island Sound.

But rather than requiring their installation, the county has so far relied on government grants and other financial incentives to persuade homeowners to abandon the cesspools and septic systems that predominate in the region. The advanced systems have an average price of nearly $20,000, at least twice the cost of traditional waste-disposal systems, which do little to limit nitrogen.

The local officials say that their support for a mandate is as much about pushing the county to act as it is about getting residents to participate in programs to restore the environment. Read the rest of the story.

How did a place like Suffolk County end up with such a subpar septic system? Cost overruns, a scandal and a murder, for starters.

Suffolk County officials had plans half a century ago for sewers throughout much of the county, from Smithtown and Huntington to Southold and East Hampton.

The reality today is that nearly 75 percent of homes in Suffolk County — some 360,000 residences — are not connected to sewers and rely instead on septic tanks and/or cesspools, through which wastewater flows into the ground and Long Island’s bays, rivers and the sound.

What happened? How does Suffolk — an upscale suburban area just outside one of the world’s major cities — find itself struggling with a problem the rest of the region handled decades ago?

The answer lies in the history of the Southwest Sewer District project of the 1970s, one of Long Island’s biggest scandals. It was supposed to be a first step in establishing the county’s sewer infrastructure, but the program was so plagued by cost overruns, mismanagement and corruption that until 10 years ago, all proposed sewer projects had become politically toxic, observers said.

And by the time elected leaders started discussing the topic again, the federal government, which along with the state paid for 87.5 percent of the costs of the Southwest Sewer District, stopped regularly funding sewer projects.

“The Southwest Sewer District scandals hit and shortly thereafter, the federal funding went away. You had the one-two punch right there,” said Dennis Kelleher, senior vice president with Melville-based engineering firm H2M Water.

An ambitious 1967 plan had sewers crossing from the South Shore of western Suffolk to Huntington, Smithtown and Commack. Voters rejected it 6 to 1.

Two years later, officials put forward a scaled-down version and ran an aggressive campaign warning that residents would otherwise essentially be drinking from their toilets.

“Long Island is the outstanding example in the world where a major population discharges sewage in groundwaters. Even people in underdeveloped countries tell me they can’t understand it,” said Dwight Metzler, New York State’s deputy health commissioner for environmental services, in a Sept. 26, 1969, Newsday article.

Voters narrowly approved it, creating the Southwest Sewer District, covering Babylon and parts of Islip.

The project was originally estimated to cost $291 million, but within four years the price was $588 million. Ultimately, the Southwest Sewer District would cost more than $1 billion and take 14 years before the first flush went through the system.

Keep reading about the history of the failed Suffolk sewer project, including the “natural-born master criminal” who was leading the project and the county official who was murdered just after he promised to reveal all the project’s secrets. Read the rest of the story.

March job levels on Long Island

The total, non-farm job count on Long Island rose 17,300 to more than 1.33 million in March 2018 compared with the same month a year earlier, according to the state Labor Department.

Sectors leading the gains were: trade, transportation and utilities, up 7,300; professional and business services, up 5,100; leisure and hospitality, up 3,800; and construction, natural resources and mining, up 3,100. Click on the charts below for details on the 10 sectors going back to 1990. Posted April 19, 2018.

Jobs in the 10 sectors on Long Island

Details on the sectors for Long Island

| Industry (job levels in thousands) | March 2018 | March 2017 | Change in year |

|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL NONFARM | 1,330.5 | 1,313.2 | 1.3% |

| TOTAL PRIVATE | 1,132.6 | 1,116.5 | 1.4% |

| Total Goods Producing | 149.7 | 147.5 | 1.5% |

| Construction, Natural Resources, Mining | 79.0 | 75.9 | 4.1% |

| Specialty Trade Contractors | 53.7 | 52.8 | 1.7% |

| Manufacturing | 70.7 | 71.6 | -1.3% |

| Durable Goods | 38.1 | 39.3 | -3.1% |

| Non-Durable Goods | 32.6 | 32.3 | 0.9% |

| Total Service Providing | 1,180.8 | 1,165.7 | 1.3% |

| Total Private Service-Providing | 982.9 | 969.0 | 1.4% |

| Trade, Transportation and Utilities | 276.8 | 269.5 | 2.7% |

| Wholesale Trade | 69.9 | 69.1 | 1.2% |

| Merchant Wholesalers, Durable Goods | 34.1 | 33.6 | 1.5% |

| Merchant Wholesalers, Nondurable Goods | 27.0 | 26.8 | 0.7% |

| Retail Trade | 162.2 | 158.0 | 2.7% |

| Building Material and Garden Equipment | 12.6 | 12.3 | 2.4% |

| Food and Beverage Stores | 36.4 | 35.8 | 1.7% |

| Grocery Stores | 30.3 | 30.1 | 0.7% |

| Health and Personal Care Stores | 13.1 | 13.1 | 0.0% |

| Clothing and Clothing Accessories Stores | 18.3 | 18.1 | 1.1% |

| General Merchandise Stores | 24.8 | 25.2 | -1.6% |

| Transportation, Warehousing, and Utilities | 44.7 | 42.4 | 5.4% |

| Utilities | 4.9 | 4.8 | 2.1% |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 39.8 | 37.6 | 5.9% |

| Couriers and Messengers | 5.8 | 5.5 | 5.5% |

| Information | 18.0 | 18.5 | -2.7% |

| Broadcasting (except Internet) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0% |

| Telecommunications | 7.8 | 8.0 | -2.5% |

| Financial Activities | 70.6 | 72.1 | -2.1% |

| Finance and Insurance | 52.4 | 54.5 | -3.9% |

| Credit Intermediation and Related Activities | 19.6 | 20.3 | -3.4% |

| Depository Credit Intermediation | 11.2 | 11.4 | -1.8% |

| Insurance Carriers and Related Activities | 26.7 | 27.2 | -1.8% |

| Real Estate and Rental and Leasing | 18.2 | 17.6 | 3.4% |

| Real Estate | 14.3 | 14.0 | 2.1% |

| Professional and Business Services | 173.1 | 168.0 | 3.0% |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 82.2 | 81.8 | 0.5% |

| Legal Services | 18.6 | 19.0 | -2.1% |

| Accounting, Tax Prep., Bookkpng., & Payroll Svcs. | 14.3 | 14.6 | -2.1% |

| Management of Companies and Enterprises | 16.2 | 16.1 | 0.6% |

| Admin. & Supp. and Waste Manage. & Remed. Svcs. | 74.7 | 70.1 | 6.6% |

| Education and Health Services | 265.6 | 266.6 | -0.4% |

| Educational Services | 43.4 | 43.6 | -0.5% |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 222.2 | 223.0 | -0.4% |

| Ambulatory Health Care Services | 85.2 | 86.5 | -1.5% |

| Hospitals | 65.7 | 64.7 | 1.5% |

| Nursing and Residential Care Facilities | 34.4 | 34.9 | -1.4% |

| Social Assistance | 36.9 | 36.9 | 0.0% |

| Leisure and Hospitality | 119.2 | 115.4 | 3.3% |

| Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation | 17.6 | 18.8 | -6.4% |

| Amusement, Gambling, and Recreation Industries | 13.4 | 14.1 | -5.0% |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 101.6 | 96.6 | 5.2% |

| Food Services and Drinking Places | 96.3 | 91.4 | 5.4% |

| Other Services | 59.6 | 58.9 | 1.2% |

| Personal and Laundry Services | 24.5 | 23.6 | 3.8% |

| Government | 197.9 | 196.7 | 0.6% |

| Federal Government | 16.0 | 16.6 | -3.6% |

| State Government | 26.0 | 25.6 | 1.6% |

| State Government Education | 14.8 | 14.1 | 5.0% |

| State Government Hospitals | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.0% |

| Local Government | 155.9 | 154.5 | 0.9% |

| Local Government Education | 105.0 | 103.7 | 1.3% |

| Local Government Hospitals | 2.7 | 2.8 | -3.6% |

What do you want to tell the new LIRR president?

Phillip Eng, a lifelong Long Islander, took over as the new president of the Long Island Rail Road this week and began with a listening tour.

Eng, 56, of Smithtown, comes to the LIRR with 35 years experience in transportation. Since joining the MTA last year, he is also a daily commuter on the Port Jefferson Branch. Whether or not you run into Eng during your commute, use this form to share your thoughts on the state of the LIRR and what its new leader needs to know.

Read more about Eng here.

Submit a responseThank you for your submission. Check back soon to see if it was posted.