Category: Health

Birth in the Era of COVID-19

One Day in an LI Maternity Ward

Fathers separated from mothers.

Empty waiting rooms.

New parents testing positive for coronavirus.

How life begins under COVID-19.

Manuel Carchipulla watched with tears in his eyes as his wife, Diana Garcia Garcia, gave birth late one night last week at Mount Sinai South Nassau hospital.

Mixed with the joy of seeing their first child was an intense sadness and pain. He had tested positive for the coronavirus that morning, April 28, so he had to watch the birth alone from more than 20 miles away, on a smartphone screen.

“It hurts me so much,” Carchipulla said in Spanish from the couple’s home in Jackson Heights, Queens, as his newborn daughter, Danaey, cried a few feet from an iPad that a surgical technologist pointed toward Garcia in a labor and delivery room in Oceanside. “But thank God it all turned out well.”

This is a birth in the era of COVID-19. Parents are sometimes separated. Moms who test positive don masks before holding their babies. And there’s an empty waiting room where family and friends once gathered in anxious anticipation.

Newsday spent April 28 in the maternity unit of South Nassau to show how COVID-19 has changed the birthing experience for parents who carry the virus — one in four mothers at the hospital had tested positive at one point — and for those who don’t.

Watch the story

The coronavirus has taken more than 3,500 lives on Long Island since the first positive case was announced on March 5 in Nassau County. At the peak of COVID-19 hospitalizations in early April, coronavirus patients crowded emergency-room hallways, and some were triaged in outdoor tents.

South Nassau has tried to shield the maternity unit from the COVID-19 crisis that envelops most of the hospital. Designated elevators that are disinfected many times each day stop only at the maternity wing, to ease prospective parents’ fears of contagion. It’s easy to at least momentarily forget a lethal pandemic when a new life is born and a smiling nurse hands a crying newborn to an elated mother.

Yet most of the maternity unit at South Nassau is almost eerily peaceful.

“Before COVID, there would be a really festive environment,” said Dr. Alan Garely, the hospital’s chair of obstetrics and gynecology. “There’d be a lot of people, a lot of food, a lot of laughter, a lot of happiness. Now it’s strictly quiet and solitary.”

No visitors have been allowed except for a support person, usually the baby’s father.

Bradley Camhi is required to leave his wife, Becky, and newborn, Fredric, two hours after delivery at Mount Sinai South Nassau hospital on April 28. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

Becky and Bradley Camhi of East Rockaway recalled how shortly after their first son, Jordan, was born two years ago, her parents and his mother were in the room celebrating, with aunts and uncles and cousins following not long after.

When son Fredric was born April 28, it was just him.

“It’s sad in a sense,” Bradley Camhi said.

Under a South Nassau rule aimed at limiting the spread of COVID-19, Bradley Camhi had to leave the hospital two hours after the birth.

That policy changed less than 24 hours later, when the state ordered all hospitals to allow a healthy primary support person to stay until the mother is discharged, and to permit doulas — trained birth coaches — in the labor and delivery room, if requested.

Family members talked with the Camhis by video after the birth, but, with social distancing, they won’t be able to see the baby even outside the hospital.

Becky Camhi, 31, said the grandparents are especially heartbroken. “It’s crushing them,” she said.

The families of Garcia and Carchipulla are in Ecuador, so after his coronavirus test came back positive, there was “no family member to accompany her” as she gave birth, Carchipulla said.

He was stunned that he had contracted the virus. Carchipulla, 32, said he quit his job as a manager and waiter at a Manhattan restaurant weeks ago, to limit his exposure to the virus, and he and his wife left home only to go to the supermarket, pharmacy or doctor’s office.

Asked as his wife was in labor how he felt being at home while she was about to give birth, he began to weep. “Very bad,” he said, putting his hands to his eyes and unable to utter another word.

A surgical technologist grabbed the iPad and brought it near the bed. Garcia was getting close to delivering.

“One more time: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10,” the doctor, nurses and surgical technologists said in a chorus, asking Garcia to push.

Manuel Carchipulla cries as he sees, via FaceTime, his wife hold their baby for the first time. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

Diana Garcia Garcia holds Danaey, who was born at 10:35 p.m. April 28 and weighed 7 pounds, 4 ounces. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

There was a collective cheer when the baby began to emerge. Garcia and, from a distance, Carchipulla, began to cry, and moments later, Danaey started to cry as well.

Soon after, Garcia, 31, pointed to the iPad and said to her daughter, “Look at Daddy.”

“Hello, my daughter,” he said, laughing through tears.

Danaey was born at 10:35 p.m., weighing 7 pounds, 4 ounces.

The surgical technologist let Carchipulla watch as the baby was cleaned and examined.

“Quiet, my love, quiet, don’t cry,” he said, a big smile on his face and tears in his eyes.

Garcia said the absence of her husband “hurts a lot.”

“A few hours ago, we were happy, preparing clothes for the baby,” she said in Spanish. “We didn’t expect this.”

On the morning of April 29, only hours after she gave birth, Garcia began to have a fever that rose to 100.5 degrees. She was tested again for the coronavirus. This time, she was positive.

Dr. Aaron Glatt, chairman of medicine and chief of infectious diseases at South Nassau, said it takes two to 14 days for the virus to show up on tests, so the two may have contracted the virus at about the same time, but, for whatever reason, Carchipulla tested positive before his wife.

Danaey tested negative, Carchipulla said, so, “for the safety of the baby,” when his wife and daughter were released from South Nassau on Friday, a distant cousin of Garcia’s picked up Danaey from the hospital and took her to Brooklyn to live with her until the couple tests negative. Carchipulla said he and Garcia are both now symptom-free.

After the positive test result, Danaey was placed in an incubator in Garcia’s hospital room.

Mothers who test positive are allowed to hold and breastfeed their newborns — the virus has not been detected in breast milk, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — but must wear masks and wash their hands regularly, said Elena Lobatch, South Nassau’s director of nursing for women and children’s services.

“A lot of hospitals still separate the mother and the baby” if the mother tests positive, Garely said. “But that’s not something we believe in, and we still advocate for the mother and for the bonding experience. We think that it’s part of child development. It’s a huge thing. There have been studies that show when mothers bond early with the babies, the relationship between the two sustains and is a stronger and better relationship.”

The hospital tries to balance the importance of that bond with the risk of transmission to the baby, he said. Children with COVID-19 generally have only mild symptoms, the CDC reports.

Manuel Carchipulla, who tested positive for COVID-19 and was not permitted to attend the birth of Danaey, cries while saying “te amo” to his daughter via FaceTime. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

Keeping the baby from the mother also isn’t practical, Lobatch said.

“Realistically, when she is going home in 24 hours, who’s going to take care of this baby?” she asked. “Mom will. Will she be breast feeding if she wants to? Absolutely. So our philosophy is we will support her here. We’re better off teaching her or guiding her to exercise good hand hygiene, good isolation practices, so she can better adjust at home. It’s not like she’s going home and she’s handing the baby away to somebody to care for. It’s her and the partner.”

And, with COVID-19, there’s “no advantage of grandma stopping by or auntie stopping by or family friends stopping by and helping,” Lobatch said.

At home, as in the hospital, mothers with the virus are advised to limit contact with their newborns as much as possible, she said.

Transmission of the coronavirus from a mother to a baby is unlikely during pregnancy, and it has not been detected in maternal fluids, such as the amniotic fluid that surrounds the fetus, according to the CDC. A very small number of babies have tested positive shortly after they were born, but it’s not clear if the infants were infected before or after birth, the CDC says.

All mothers and their partners at South Nassau are tested for the coronavirus upon or before admission, and 18% of moms who have delivered since late March at the hospital have tested positive — down from 27% on April 13, a reflection of the success of social isolation efforts, Garely said.

Four of the women were seriously ill and required oxygen delivered through masks or nasal prongs, and their newborns were cared for in a separate room, Lobatch said. One of the women had such severe breathing problems that she was induced to go into labor at 34 weeks “to help her disease and to help the chances for the baby,” Garely said. The mother recovered after more than a week of treatment in the hospital, and the baby was healthy. The other mothers also recovered.

The rest have been asymptomatic or had only mild symptoms. Their babies were placed in the same room, but at least 6 feet away, and nurses made frequent rounds to check on them, said Patricia Bartels, nurse manager for labor and delivery.

The babies are tested 24 hours after birth, and 24 hours after that, if they’re still at the hospital, Garely said. If the baby is not in the hospital 48 hours later, the mother is asked to obtain a test for her baby at a pediatrician’s office. None of the newborns has tested positive, Garely said.

“It confirms the assumption that the virus is not transmitted through the placenta and the babies are born uninfected,” he said.

Partners who test positive have the same rules for contact with the baby as moms who test positive, including holding the baby only with a surgical mask covering the nose and mouth, Lobatch said.

Shannon Koledin, 28, was without her husband when their daughter, Mikaela, was born April 28 at Mount Sinai South Nassau hospital. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

With family forced to stay away, Shannon Koledin looks over at Mikaela in her room at Mount Sinai South Nassau. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

Michael Koledin, who tested positive for the coronavirus before Mikaela was born, sees his wife and newborn child on FaceTime on April 28. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger

Yet Michael Koledin, who tested positive for the coronavirus before his daughter, Mikaela, was born early April 28, was still wary and only held her briefly, with a mask and gloves, when she came home with his wife, Shannon, the next day.

“I’m definitely nervous about it,” he said. “There are a lot of unknowns about COVID-19.”

Koledin, 31, an FDNY firefighter in Queens, first tested positive on April 3. He had body aches and mild fever, but lately only a cough and mild headache were lingering, and it was getting better, making him assume he no longer carried the virus.

“When I found out he tested positive again, I think I cried for the rest of the night,” Shannon Koledin, 28, said.

Michael Koledin has been living in the den of the couple’s Massapequa home and will continue doing so until after he’s symptom-free.

During Mikaela’s birth, Shannon’s mother was with her, but “I just wanted that moment of when she was born to have him with me and to experience it together,” Shannon said. “It’s our first baby.”

Instead, he watched the birth on FaceTime.

A few hours later, Shannon lay in a quiet room that, she said, probably would have had a steady stream of family and friends visiting — along with Michael, of course, who instead was only an image on a computer screen.

Michael said the morning of his daughter’s birth, FaceTime “did make me feel like I was a part of the process and I was there for her. I don’t think it really took away from the moment. I still cried when I saw my daughter.”

He doesn’t dwell on not being able to kiss his newborn, or on how different it would have been if he hadn’t become a dad during a pandemic.

“It was such a joyful moment,” Michael said. “So I feel if I have regrets about it, it will take away from the joy.”

Think you know Pilgrim Psychiatric Center? Go inside to see how drastically it’s changed.

A farm with a therapy llama, pig and goats …

A swimming pool, bowling alley and greenhouse …

This is what you’ll find at Pilgrim Psychiatric Center in Brentwood nowadays.

What was once a place that inspired fear and resembled some scenes from the Jack Nicholson film, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” …

Where thousands of patients were crowded inside, some enduring lobotomies and never leaving the complex …

Is now embracing modern approaches to mental health that give patients more control over their treatment and help them return to their lives outside Pilgrim.

Nearly 14,000 people lived on the sprawling grounds of Pilgrim Psychiatric Center in the Brentwood of the 1950s, an era when lobotomies and induced comas were viewed as acceptable treatments for mental illness.

Today, the state-run Pilgrim — once the world’s largest psychiatric center — is, with its 273 beds, a fragment of its former self. Unlike in the past, its approach to treatment now focuses on getting patients out of the hospital rather than keeping them in, and residents have input on their own care.

“The expectation then was to go into hospitals and stay there for years,” said Kathy O’Keefe, executive director of Pilgrim. Today, she said, “We ready people for discharge the minute they walk through the door.”

Pilgrim opened in 1931 on 825 acres of what was then countryside to relieve overcrowding at other state-run institutions. “A City of the Insane It Grows Every Day,” read a 1938 Life magazine headline about Pilgrim.

Pilgrim sits on about 300 acres and is the third-largest of the state’s 23 psychiatric centers. The center only treats people with the most severe needs. Most are diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder, which is a combination of symptoms associated with schizophrenia and a mood disorder. In addition, they typically have complicating factors such as severe emotional trauma or substance abuse, or a low IQ, which makes insight into their condition more difficult, O’Keefe said.

The imposing 80-year-old center has homey touches, such as patient-decorated bedrooms. Yet the seven-story brick building has an institutional feel. With two-thirds of residents arriving as involuntary admissions — most because they are legally considered a danger to themselves; some a danger to others — it is highly secure, with locked patient wings and an entrance with two electronic doors.

It costs an average of $973 a day to treat and house each resident, O’Keefe said, and state figures put the total inpatient cost for the 2019-20 fiscal year at about $87 million. Pilgrim had annual budgets of about $12 million in 1954 and 1955, using mid-1950s dollars, Newsday reported then. There are about 1,000 employees today, O’Keefe said, compared with the 4,000 that Newsday reported worked there in the late 1950s.

Factors such as the rise of psychiatric medications, a push for expanded rights for mentally ill people, and media exposures of abuse and neglect spurred a decadeslong drop in the population of long-term psychiatric centers in New York and nationwide, said Nancy Tomes, a history professor at Stony Brook University who’s studied the mental health care system’s changes.

Elizabeth Hancq, research director for the Arlington, Virginia-based Treatment Advocacy Center, which promotes expanded access to treatment, said that, overall, the migration of people out of long-term institutions and into communities was positive.

But, she said, deinstitutionalization went too far, and there are far fewer long-term psychiatric beds than needed nationwide. “The evidence for the need for this longer-term care setting such as state hospitals or other 24-hour hospital-level care is seen every day throughout the country” in one third of homeless people and one fourth of jail inmates with serious mental illnesses, she said.

Most Pilgrim buildings were torn down years ago. Others remain vacant, boarded up and defaced by graffiti. The state in 2002 sold 452 acres to developer Jerry Wolkoff for his long-stalled Heartland Town Square project, which would include 9,000 residential units and office and retail space in Brentwood. The project is on hold because of lawsuits and Wolfkoff’s inability to get Suffolk County approval for a sewer connection.

For patients who remained at places like Pilgrim, after the exodus from large institutions began in the 1950s, there often was “a deadening quality” to life, Tomes said, with drugs that left them in a stupor, a paucity of fulfilling activities and a warehousing of people rather than any real attempt at treatment to prepare them for life on the outside.

The portrayal in Hollywood movies like “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” of numbed, overmedicated residents cowed into docility was largely accurate, said Joseph Rogers, who has bipolar disorder and has spent decades helping lead Pennsylvania-based mental health organizations. Rogers said he lived “kind of in a walking coma” at a Florida psychiatric center in the early 1970s.

Since then, drugs have improved and have less severe side effects, O’Keefe said. Therapists at Pilgrim today discuss medication with patients rather than coerce them to take it. Only in rare cases involving dangerous patients is a court order sought to forcibly administer medications, she said.

Likewise, patients “are signing off on their treatment plan,” said Stephen Berg, Pilgrim’s director of operations.

Patient Story

He heard voices. He once set fire to his home. Pilgrim helped him 'come back to the world, the real world'

When Larry Euell Jr. was 18, he was convinced voices coming out of the radio were talking about him. Three years later, while in a rage, he started a fire in his bedroom and almost burned down his family’s house.

That fire culminated with him being sent to Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, where four years of treatment left Euell, now 34, of Hempstead, happier and optimistic.

“What Pilgrim did was transition me to come back to the world, the real world,” he said.

While at Pilgrim from 2011 to 2015, Euell was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. “I thought I was going to be institutionalized for the rest of my life,” he said.

He is now studying fashion design at Nassau Community College — something he never thought would have been possible.

College attendance is “very obtainable by many people with this disorder, more people than we can probably appreciate,” said Dr. Lisa Dixon, a professor of psychiatry at the New York State Psychiatric Institute in Manhattan and an expert on schizophrenia. “For some people, this illness is highly disabling, but there’s a significant number of people who have this illness who are able to live very fulfilling lives.”

Public perceptions of individuals with schizophrenia often are inaccurate, research shows. About 60% of Americans incorrectly believe violence is a symptom of schizophrenia, according to a 2008 survey commissioned by the National Alliance on Mental Illness, an advocacy, education and support group based in Arlington, Virginia.

“At Pilgrim, I had to learn how to actually put my coping skills into action…”

Larry Euell Jr.

In reality, Dixon said, even though people with schizophrenia are slightly more likely to commit violent acts than the general population, the large majority of people with schizophrenia are not violent toward others.

The scarring on Euell’s face and arms are lifelong markers of when he was at his nadir. The paranoia was intense, the depression deep.

“I thought people were out to get me,” he said. “I thought everyone was against me. I didn’t feel I had any love. I didn’t think anyone loved me, even though my mom was very loving and supported me the best she could.”

One day when he was 19, he stayed up all night writing random words on a piece of paper and then started talking gibberish to his mother. She panicked and called the Nassau County mobile crisis team, which comprises social workers and nurses trained to help people with mental health emergencies. Following that crisis, he spent more than two weeks at two community psychiatric hospitals and, upon release, was prescribed medication, which he didn’t take because it made him drowsy.

As his paranoia increased, he said he stopped hanging out with some friends, thinking they had it in for him. In November 2006, he took 30 days of prescribed medication he had stashed in his drawers. It provoked a frenzy, causing him to shout, throw and break things, as he ran around the Hempstead house he shared with his mother, grandmother and three younger brothers.

“Everything kind of got to me,” he said. “The paranoia, the distorted thinking, thinking people were out to get me.”

While trashing his bedroom, he knocked a lit incense burner onto the carpet, starting a fire that consumed his bedroom, he said. Firefighters pulled him out of the charred room.

Euell was arrested and pleaded not responsible by reason of mental disease or defect to second-degree arson and reckless endangerment charges, according to court records. He was sent to the upstate Mid-Hudson Forensic Psychiatric Center, which provides mental health treatment for people sent by court order. At the time, he had a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder; the diagnosis was changed to paranoid schnizophrenia at Pilgrim.

He referred to his four years at Mid-Hudson as “my wake-up call.”

“That was the beginning of me realizing I had a problem, and I needed to find a way to deal with it,” he added. “Before that, I felt I was just a regular person mad at the world.”

After Mid-Hudson, he spent the four years at Pilgrim. Therapists at Mid-Hudson made him realize his paranoia was a symptom of an illness, and that others were experiencing the same types of feelings. Euell said Pilgrim taught him how to use that insight and the anger management and other coping skills he had learned at Mid-Hudson to prepare him to live outside the walls of a psychiatric center.

“I had to learn how to actually put my coping skills into action, to calm my anxiousness,” he said.

He began understanding how to not let distractions get to him.

“With the paranoia, it all kind of hits you,” he said. “You could be in a crowded area and [feel that] everybody is just looking at you or something. You just have to focus on what you’re doing and get your task done.”

Medications — he takes the antipsychotic drug Haldol — help but they’re not enough, he said.

Euell took poetry and art classes at Pilgrim and began writing music, which gave him an outlet for his creativity. He felt confident enough to set a goal of attending college for fashion design, and that motivated him to study for the GED diploma he earned at Pilgrim. He hopes to attend the Fashion Institute of Technology in Manhattan.

“I have a real good focus now,” he said. “It’s like a beam. Nothing can penetrate the beam.”

Treatment sometimes is introduced gradually, to gain the resident’s acquiescence, and peer specialists — people who are in recovery from mental illness and work at Pilgrim — sometimes will talk with residents about the benefits, Berg said. Therapy, for example, “is only productive if the person really wants to be participating,” he said.

Zoe Pasquier, 38, a peer specialist at Pilgrim for more than six years, said she talks to residents about how therapy, medication and support groups can be helpful. She said sharing her own story can “create a safe space for someone to be able to share things, so maybe they won’t feel as judged.”

O’Keefe recently stood in a kitchen inside Pilgrim that is part of the center’s “discharge academy,” a program of typically eight to 10 weeks in which residents are taught meal preparation, shopping, budgeting, resume-writing and other skills they’ll need to live independently or semi-independently.

The academy illustrates the shift in emphasis toward moving residents out of Pilgrim to smaller group residences where they can live in a less institutional atmosphere, or to apartments where they may live with others or on their own, O’Keefe said. Often, a group residence is a transitional step toward independent living. People upon discharge are set up with outpatient treatment, and Pilgrim staff check up on them, O’Keefe said. Most former Pilgrim residents continue to need medication and some type of outpatient treatment after leaving the center, she said.

Several decades ago, it was common for people to spend the rest of their lives at Pilgrim after admission, O’Keefe said, and even at the turn of the millennium there was “a culture of … no rush to move people through. We wanted to fix everything about them before they got out of our hospital. We just don’t think that way anymore.”

A typical stay at Pilgrim today is six to nine months. A small number still stay years, especially if they continue to present a danger to themselves or others, O’Keefe said.

Patient Story

She always feared Pilgrim from afar, but it helped her regain control after 11 suicide attempts

Even in the depths of the depression and uncontrollable mania caused by her bipolar disorder, Alarece Matos couldn’t imagine herself at Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, a place she feared while growing up a few miles away.

“When you look at Pilgrim on the outside and you’ve never been there before, you think of ‘mental institution’ — those movies, you think of people running around screaming and throwing their hands in the air and hurting each other,” the Middle Island woman said. “You don’t think of a place where you can go and get help.”

After attempting suicide 11 times, losing job after job, and obtaining largely ineffective care seven times at shorter-term community psychiatric hospitals, Matos credits Pilgrim with turning her life around.

“I’m looking forward to going back to work and this time being able to keep a job,” said Matos, who is living independently and studying to earn a medical office administration certificate at Hunter Business School in Medford. “With the coping skills I have now, I’ve learned how to be able to function in society the way I should.”

Matos, 41, said she lost 10 jobs, mostly in telephone customer service, after customer complaints of either gushing friendliness when she was manic, or rudeness when she was depressed, or after bosses and co-workers became fed up with excessive perkiness one day and intense negativity the next.

“The times I would show up to work manic, they would think I was on drugs,” she said. “And there were times I was so depressed, I would call in sick because I didn’t want to be around anyone, I didn’t want to get up. With all the call-ins, you lose your job, because you become unreliable.”

“When I tell someone I’ve been to Pilgrim, they’re like, ‘Oh, God, you’ve been to Pilgrim?'”

Alarece Matos

Her typical stays of three to four weeks at community psychiatric hospitals provided temporary help, but after she left, she stopped taking her medication and didn’t keep appointments with outpatient therapists.

In late 2016, Matos was traumatized when a woman she believes had an untreated mental illness tried to kill her at a Brooklyn homeless shelter where the two were living.

Matos said she woke up one night to find the woman on top of her with her hands around her neck, trying to choke her. She was able to fight the woman off, and a few days later, she checked into Stony Brook University Hospital’s psychiatric unit, where a therapist’s description of Pilgrim’s approach to treatment dispelled Matos’ longtime fears about the center. She voluntarily checked in.

Matos said a key reason her six months at Pilgrim succeeded, where previous professional treatment failed, is peer specialists, people who work at Pilgrim who themselves have a diagnosed mental illness. They are trained to help those just entering recovery or early along in the process.

She could relate more to peer specialists than therapists and psychiatrists.

“It made it a lot easier because it wasn’t just someone saying, ‘Aw, you’re going to be OK,’ ” Matos said. “It’s someone actually telling you, ‘It’s going to be fine. I’ve been through this; it takes time, but you can do it.’ “

The emergence of peer specialists is one of the biggest changes at Pilgrim, said Kathy O’Keefe, the center’s executive director. As recently as two decades ago, the common thinking among mental health experts was that someone with a mental illness likely couldn’t help another person with a psychiatric disorder, O’Keefe said.

“Now, there’s an acknowledgment that having a community behind you keeps patients from feeling isolated,” said Stephen Berg, Pilgrim’s operations director.

Matos said the medication she takes — Latuda and Lamictal — and therapy have helped control her mania and depression. But they haven’t entirely eliminated them. Pilgrim taught her ways to cope.

“If I feel my mania coming on, I go for a walk” or call a family member, a former Pilgrim resident or peer specialist, she said.

While at Pilgrim, she began painting and meditating to help reduce anxiety and depression.

Matos regularly confronts misunderstandings about Pilgrim and mental illness.

“When I tell someone I’ve been to Pilgrim, they’re like, ‘Oh, God, you’ve been to Pilgrim? So you’re crazy?’ ” she said.

The stigma of mental illness — and of psychiatric centers such as Pilgrim — prevents many people from acknowledging even to themselves that they need help, Matos said.

Yet without Pilgrim, Matos believes the mania, depression and anxiety that she has struggled with for years would still be controlling her instead of her controlling them.

“Pilgrim helped me see it’s OK to be who you are,” she said. “It’s OK if people don’t understand. As long as you know who you are and you want to get better, that’s what’s important.”

A small percentage of Pilgrim patients arrive via the courts, and most are people who committed nonviolent offenses such as trespassing and are judged incapable of understanding their crimes, O’Keefe said.

The majority of involuntary admissions involve people deemed a danger to themselves — either because they may harm themselves deliberately or because self-neglect could lead to infections, homelessness or other problems, O’Keefe said. Two psychiatrists must approve involuntary admissions, most of which are transfers from community psychiatric hospitals.

Fewer than 20% of patients are considered a danger to others, and various strategies are used to stabilize them, including medications and in some cases temporary stays in a special treatment unit, O’Keefe said.

About a quarter of Pilgrim patients are black, much higher than the 9% of Long Island residents who are black. Currently, 63% of Pilgrim patients are white, 9% are Hispanic and less than 1% are Asian or American Indian, O’Keefe said. Those numbers can fluctuate, she said.

Nationwide, black adults are twice as likely as white adults to receive inpatient mental health care, according to a 2015 report by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Dr. Danielle Hairston, director of the residency program in psychiatry at Howard University in Washington, D.C., and president of the American Psychiatric Association’s Black Caucus, said that’s partly because black people with mental illness are less likely to seek treatment early on, and that can lead to worsening symptoms and inpatient admission. The reluctance stems from factors such as the dearth of black psychiatrists who black mentally ill people can relate to and generations of mistrust due to a long history of unjustified institutionalization of black people, she said.

In addition, Hairston said, studies show that a black person with similar symptoms of mental illness as a white person is more likely to be seen as psychotic, and aggressive and agitated, and in need of inpatient care — evidence of conscious and unconscious bias among psychiatrists.

The 273 patient beds at Pilgrim are less than half the 610 beds in 2008, but there are no plans to further reduce the number of patients, O’Keefe said.

Rogers thinks large institutions like Pilgrim should close and be replaced by small residences. People in large psychiatric centers are typically “forgotten,” don’t get adequate care and live under burdensome restrictions, he said.

“If somebody needs long-term support, that should be done in the community,” he said.

But Hancq contends it is not economically feasible for small community-based residences to have the specialized staff and expansive treatment programs of large state psychiatric centers.

At Pilgrim, there are dozens of classes tailored to individual needs, such as courses on how to become more assertive, how to make friends and how to control anger and avoid conflict. There are specialized programs, such as for people with a compulsion to drink so much water it can kill them.

A recreation center aids in therapy, as does a farm with goats, sheep, a llama, guinea pigs and rabbits, Berg said.

“Sometimes when we have nonverbal clients who have trouble forming associations, they learn to interact and form a relationship with the animals,” Berg said. “Animals are nonthreatening and they don’t yell back at you. Psychologists use that to form human relationships.”

A multisensory room with flashing lights, loud music, plastic tubes with bubbly water, a rocking chair, a disco ball and an “aroma fan” that emits calming scents is used especially for patients who are not responding as well to other treatment, he said.

Patients choose the type of music to play — or whether they even want music — and how much stimulation they want. There are drums to bang, wheels to turn and balls to squeeze for those who can benefit from it. The room’s features can make patients less anxious and more receptive to treatment, Berg said. Psychologists observe the patient, and they are ready to talk when the patient is, he said.

Jayette Lansbury, president of the Huntington chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, a Virginia-based group that advocates for people with mental illness, said treatment at Pilgrim has benefited many people.

“I’ve heard nothing but good reviews from the patients’ point of view and their families’ point of view,” she said. “It’s a caring environment.”

Pilgrim and mental health through the decades

1931

Pilgrim State Hospital opens on 825 acres with 100 patients.

1949

Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz receives a Nobel Prize for developing the surgery later known as a lobotomy, one of the extreme procedures used at Pilgrim and elsewhere that was later discredited.

1954

Pilgrim reaches its peak patient population of 13,875. It was then the largest psychiatric center in the world.

1963

Enactment of the Community Mental Health Act, which provides federal funding to build community-based mental-health centers. It — along with the introduction in the 1950s of more effective psychiatric medications and, later, Medicaid funding — helps lead to deinstitutionalization, the move of tens of thousands of mentally ill people out of large state institutions. Critics said there has never been enough money for community-based treatment and housing, so many people did not receive services.

1975

The U.S. Supreme Court rules that a person must be a danger to one’s self or others to be forcibly confined to a psychiatric center.

1992

There are 1,682 residents at Pilgrim.

1996

Central Islip and Kings Park psychiatric centers close. Services, patients transferred to Pilgrim.

2002

Developer Jerry Wolkoff buys 452 acres of Pilgrim property from the state. He later says he is planning 9,000 residential units and 4.4 million square feet of office and retail space for a project dubbed Heartland Town Square.

2008

Pilgrim patient population is 610.

2019

Judge dismisses Wolkoff suit against Suffolk County for not granting approval to connect the Heartland project with the Southwest Sewer District. Another lawsuit, filed by the Brentwood school district and others against Wolkoff and the Islip Town board to block the Heartland project, remains unresolved. Islip in 2017 gave approval to the first phase of Heartland.

2020

There are 273 patient beds at Pilgrim, with no plans to reduce the patient population further.

SOURCES: Pilgrim Psychiatric Center, New York State Office of Mental Health, U.S. Supreme Court, court records, Newsday reporting, Nobel Foundation

10 tips for battling pollen this season

Credit: Newsday / Thomas A. Ferrara

So the warm weather has finally arrived and you want to enjoy it this weekend. But with the gorgeous weather has come an ugly truth: It’s allergy season.

The overload of pollen can be blamed on April’s cooler temperatures, which led trees and plants to slow down the blooming process, says Evan Dackow, a certified arborist and an allergy sufferer.

With temperatures now cranked up to 80 degrees and higher, “everything is coming to bloom right now” as we’re getting three weeks of pollen production all at once.

Here are some ideas to get through the big bloom:

The best times to be outdoors is actually on cool, rainy days, as the precipitation moistens pollen and keeps it on the ground. The worst time — when pollen counts are highest — are warm, dry, breezy days, when the wind blows the pollen around.

If you must go out, pull hair back and wear a hat and sunglasses.

Those who are driven to be outdoors — gardeners, runners, dog walkers — can consider wearing pollen masks. The American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology suggests National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health rated 95 filter masks.

Get to the shore as often as possible on higher-pollen days. Short on trees and grasses, the beach is not a pollen-friendly environment, though it’s not necessarily a pollen-free zone.

Keep windows closed at home (also in your car) and rely on air conditioners, set to recirculate mode, says Dr. Ilene Goldstein, an allergist in Huntington and Smithtown who’s also president of the Long Island Allergy Society.

Look for air purifiers and vacuums that use high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters. Pictured, a vacuum cleaner’s HEPA filter.

Remove pollen-laden shoes and clothes when you come indoors, and brush your pets before letting them inside. Consider bathing them once a week if possible. You might want to break out the mask again while doing this.

Look at your bedroom as a safety zone, a place where you spend six to eight hours of every day, says Dr. K.C. Rondello, allergy sufferer and professor at the Adelphi University College of Nursing and Public Health. That means taking special care to keep it as pollen free as possible, changing/washing bedding every few days, bathing yourself and washing your hair every single night.

In addition to frequent hand-washing, start training yourself to minimize the number of times your hands make contact with (and transmit bits of pollen to) your face, says Rondello. Each time you rub an eye, pull at an ear, brush hair away, you’re “introducing the offending agent” to the neighborhood of mucus membranes, where irritation is the greatest.

Resources:

Allergy & Asthma Network – http://www.allergyasthmanetwork.org/

American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology – http://acaai.org/

Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America – http://www.aafa.org/http://www.asthmaandallergyfriendly.com/

Some popular hashtags: #pollen #allergytips #allergies #hayfever #hayfevertips

How the latest Obamacare repeal bill would affect New York State

The legislation that Senate Republicans hope to pass next week in a last-ditch effort to dismantle Obamacare would strip away some of the federal funds sent to New York and other states for expanding Medicaid – and give them to the states that didn’t.

The conversion of Affordable Care Act funds into state block grants from 2020 to 2026 is one key part of the bill that Senate Republicans will bring up for a vote by the end of the month, before the expiration of special budget rules that allow passage by a simple majority.

How New York State would be affected

The bill would put the ACA’s financing for subsidized private health insurance and Medicaid expansion into a giant pot and redistribute it among states according to new formulas.

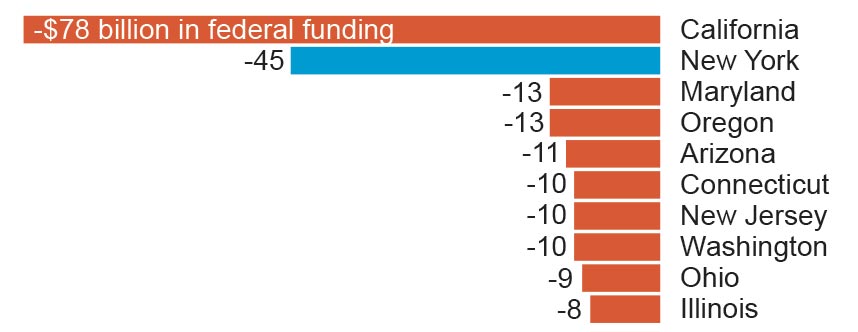

New York would lose $45 billion under the bill’s conversion of Affordable Care Act funds into state block grants from 2020 to 2026, the Avalere consulting firm said.

The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, a think tank that favors the current health law, said New York State would lose $18.9 billion in 2026 alone.

Here’s a look at the 10 states that would lose the most in federal funding if the bill becomes law:

How New York leaders have responded

Supporters of the bill say governors and state legislatures would have broad leeway on how to spend the money, and could also seek federal waivers allowing them to modify insurance market safeguards for consumers. For example, states could let insurers charge higher premiums for older adults.

But with that flexibility also comes the challenge of fixing a broken health care system with less money, a task that New York Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo and at least 10 other governors have publicly rejected.

“I would not trade $19 billion for the flexibility. Because if they cut us $19 billion, if I was as flexible as a Gumby doll, we could not fund our healthcare system,” Cuomo said. “It also puts 2.7 million New Yorkers at risk of losing their health insurance.”

#GrahamCassidy will hurt New Yorkers, who could lose nearly $19 billion in health care funding.

— Kirsten Gillibrand (@SenGillibrand) September 19, 2017

New #Trumpcare would cause millions to lose coverage, eliminates protections for ppl w/ pre-existing conditions & ups out-of-pocket costs.

— Chuck Schumer (@SenSchumer) September 19, 2017

The bill also repeals requirements that individuals buy health insurance and employers offer it, ends subsidies to help people pay premiums, cuts off funding for Medicaid expansion, and makes significant cuts as its reshapes Medicaid.

“They are designed, these cuts, to hurt states that have expanded Medicaid,” Cuomo said. “To penalize us for doing a better job than other states is a gross unfairness.”

Residents of New York and California, which expanded Medicaid and set up insurance marketplaces, had fared better than people living in Texas and Florida, which opted out of both, according to a March 2017 study by the Commonwealth Fund, which studies health issues.

If the bill passes in the Senate, it faces a difficult path in the House, said Rep. Peter King (R-Seaford), who opposes the bill because of the funding cuts for New York.

To penalize us for doing a better job than other states is a gross unfairness.– Gov. Andrew Cuomo

How other states would be affected

The bill would lead to an overall $215 billion cut to states in federal funding for health insurance, through 2026. Reductions would grow over time.

A reduction in federal subsidies for health insurance likely would lead to more people being uninsured, said Caroline Pearson, a senior vice president at Avalere, which specializes in health industry research.

Thirty-four states would see cuts by 2026, while 16 would see increases. Among the losers are several states that were key for President Donald Trump’s election, including Florida, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Ohio.

California would lose $78 billion, while Texas and Georgia would gain $35 billion and $10 billion, respectively.

“If you’re in a state which has not expanded Medicaid, you’re going to do great,” said Cassidy. “If you’re a state which has expanded Medicaid, we do our best to hold you harmless.”

What else would the bill do?

Named for the bill’s sponsors, Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), and Bill Cassidy (R-La.), the bill would repeal much of the Obama-era Affordable Care Act and limit future federal funding for Medicaid. That federal-state health insurance program covers more than 70 million low-income people, ranging from newborns to elderly nursing home residents.

I would not sign Graham-Cassidy if it did not include coverage of pre-existing conditions. It does! A great Bill. Repeal & Replace.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 20, 2017

Independent analysts say the latest Senate Republican bill is likely to leave more people uninsured than the Affordable Care Act, and allow states to make changes that raise costs for people with health problems or pre-existing medical conditions.

The Congressional Budget Office has said it doesn’t have time to complete a full analysis of the impact on coverage before the deadline.

How would Medicaid spending be affected?

Compared to current projected levels, Medicaid spending would be reduced by more than $1 trillion, or 12 percent, from 2020-2036, a study by consulting firm Avalere found. Earlier independent congressional budget analysts said such Medicaid cuts could leave millions more uninsured.

Here’s how else the bill compares

Medicaid expansion

Current: States have the option to expand Medicaid to cover more low-income adults, with the federal government picking up most of the cost.

Senate bill: Ends the federal match for Medicaid’s expansion; ends program’s status as an open-ended entitlement, replacing it with a per-person cap.

Health status-based rates

Current: People cannot be denied coverage due to pre-existing medical problems, nor can they be charged more because of poor health.

Senate bill: Prohibits denying coverage to those with pre-existing condition, but states can seek waivers to let insurers charge more based on health status in some cases.

Subsidies for insurance

Current: Provides income-based subsidies to help with premiums and out-of-pocket costs such as deductibles and copayments; subsidy benchmark tied to mid-level “silver” plans.

Senate bill: Replaces income-based subsidies with block grants to states for health care programs; ends cost-sharing subsidies in 2020.

Standard health benefits

Current: Requires insurers to cover 10 broad “essential services” such as hospitalization, prescriptions, substance abuse treatment, preventive services, maternity and childbirth.

Senate bill: Allows states to seek waivers from the benefits requirement as part of the block grant program.

Coverage mandate

Current: Requires those deemed able to afford coverage to carry a policy or risk fines from the IRS; requires larger employers to offer coverage to full-time workers.

Senate bill: Repeals coverage mandate by removing tax penalty beginning with the 2016 tax year.

Planned Parenthood

Current: Planned Parenthood is eligible for Medicaid reimbursements, but federal money cannot fund abortions.

Senate bill: Planned Parenthood would face a one-year Medicaid funding freeze.

Sources: Department of Health and Human Services, Kaiser Family Foundation

WITH WASHINGTON POST

How the GOP health-care bill could affect you

WASHINGTON – President Donald Trump and Republicans who control Congress are advancing a sweeping health-care bill that would make some significant changes to “Obamacare” but not completely repeal the current national health care law. In fact, the GOP proposal would keep some significant elements of Obamacare.

Many specifics are not yet known but here is a look at some of the changes and how they might impact people in different age groups, based on examples offered by the Kaiser Foundation and the Congressional Budget Office.

Use the arrows to the right of each section to navigate through this project.

Mandate vs. choice

The mandate that every individual get health insurance or pay a penalty to offset health-care costs would be eliminated. Also, large employers would no longer have to cover workers or face a penalty if they don’t.

Philosophically, this is the crucial hinge for many Republicans: switching from mandates to choices.

“It comes down to whether you want government playing a predominant role in determining what (health care coverage) should be offered in or whether you think (insurers) should be allowed to offer plans” that fit the market, said Rep. John Faso (R-Kinderhook), the lone New York Republican on the House Budget Committee. “The ACA represents a centralized approach. The Republican approach lets the market work and lets individuals decide what to buy.”

Tax credits:

The Republican plan would replace Obamacare tax credits with a different kind of tax credit. In short, Obamacare provided tax credits based on incomes and costs of policies; the GOP would base it on age. Further, the GOP would cap the maximum credit at $4,000 for people 60 years old or greater; under Obamacare, the credits could be $10,000 or more.

Enrollment and premiums:

The Congressional Budget Office projected that health-care premiums would spike 20 percent for those buying in the individual market during the first 10 years, but decline by 10 percent overall in a decade. But again, individual circumstances can vary widely.

Medicaid:

The GOP plan would keep federal funding of Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion through 2020, but halt it after that. The expansion had allowed people who earned just enough money to be excluded from Medicaid to join it. That will end. People in this income category will be among those most affected, in the future, by the proposed changes.

Popular elements of Obamacare:

The GOP would keep some key parts of the ACA that are popular: Insurers wouldn’t be able to deny coverage to people with pre-existing conditions; children would be able to stay on their parents’ policies until age 26; insurers can’t cap annual or lifetime medical expenses.

Women’s health issues:

The GOP would freeze Planned Parenthood funding for one year. The organization gets nearly half its funding from the federal government, according to Associated Press, and the aid doesn’t pay for abortions but rather other services such as birth control and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases.

Further, the GOP plan prohibits the use of tax credits to purchase any health plan that covers abortions.

Mental health, substance abuse:

For the 31 states that expanded Medicaid under Obamacare (including New York), the GOP plan would eliminate (in 2020) the requirement that Medicaid cover mental-health and substance-abuse treatment. That doesn’t mean states won’t continue to cover those services, but they will be among the mix of coverage choices.

Some Democrats and some health-policy groups view this as a “major retreat” from substance-abuse treatment.

You’ll be able to stay on your parent’s policy until age 26. The GOP would keep this popular provision of the ACA.

Also read the section for ANY age to learn more about possible changes in coverage.

If you get health insurance through your job, the GOP plan would not have a huge effect on you, said Bill Hammond, a health-care policy analyst at the Empire Center.

The overwhelming majority of companies provide health insurance because it is part of the traditional package to attract employees or “because they think it’s the right thing to do,” Hammond said. The removal of the penalties likely won’t spur companies to suddenly drop coverage.

That said, companies could alter what their policies cover based on how the market shakes out. The Congressional Budget Office projected that up to 7 million fewer people would be covered through work-offered insurance by 2026 because companies no longer face a penalty. Republicans called that estimate overstated.

Also read the section for ANY age to learn more about possible changes in coverage.

Like the ACA, the Republican plan primarily affects those who must buy insurance on their own — especially young adults and senior citizens. And the impact depends on a person’s circumstances.

If you are a Long Islander who is 27 (no longer covered by your parent’s policies) and you are earning less than $50,000, you’d fare better under Obamacare. If you were earning more than that (up to $75,000), you’d fare better under the GOP plan.

But it’s not just tax credits that would change, it’s likely premiums would too. Younger individuals likely would see lower insurance premiums. That’s because the GOP plan, according to supporters, recognizes that young people have fewer health costs and should pay less.

Also read the section for ANY age to learn more about possible changes in coverage.

If you get health insurance through your job, the GOP plan would not have a huge effect on you, said Bill Hammond, a health-care policy analyst at the Empire Center.

The overwhelming majority of companies provide health insurance because it is part of the traditional package to attract employees or “because they think it’s the right thing to do,” Hammond said. The removal of the penalties likely won’t spur companies to suddenly drop coverage.

That said, companies could alter what their policies cover based on how the market shakes out. The Congressional Budget Office projected that up to 7 million fewer people would be covered through work-offered insurance by 2026 because companies no longer face a penalty. Republicans called that estimate overstated.

Also read the section for ANY age to learn more about possible changes in coverage.

Like the ACA, the Republican plan primarily affects those who must buy insurance on their own – especially young adults and senior citizens. And the impact depends on a person’s circumstances.

If you are a 40-year-old Long Islander and your income is $30,000, you’d be eligible for $3,000 in tax credits under the GOP plan and $3,930 under Obamacare, according to Kaiser. That same person earning $75,000 in income would fare better under the GOP plan because his income level is too high to get any tax credits under Obamacare. (If that person earns $100,000 or more, he/she could get just $500 in tax credits in the GOP plan.)

But it’s not just tax credits that would change, it’s likely premiums would too. The CBO projected that premiums for a 40-year-old are likely to decrease.

Those who currently earn too much to qualify for Medicaid or Obamacare subsidies likely would fare better under the GOP plan. For example, a 40-year-old who earns $68,200 annually would pay $6,500 in premiums under Obamacare but $2,400 under the GOP plan.

Also see changes for ANY age to read more about changes that could affect your coverage.

If you get health insurance through your job, the GOP plan would not have a huge effect on you, said Bill Hammond, a health-care policy analyst at the Empire Center.

The overwhelming majority of companies provide health insurance because it is part of the traditional package to attract employees or “because they think it’s the right thing to do,” Hammond said. The removal of the penalties likely won’t spur companies to suddenly drop coverage.

That said, companies could alter what their policies cover based on how the market shakes out. The Congressional Budget Office projected that up to 7 million fewer people would be covered through work-offered insurance by 2026 because companies no longer face a penalty. Republicans called that estimate overstated.

Also read the section for ANY age to learn more about possible changes in coverage.

If you a Long Islander 60 or older and your income is $30,000, it’s essentially a wash: you’d be eligible for $4,000 in tax credits under the GOP plan and $3,930 under Obamacare, according to Kaiser. That same person earning $75,000 in income would fare better under the GOP plan because his income level is too high to get any tax credits under Obamacare. (If that person earns $100,000 or more, he/she could get just $1,500 in tax credits in the GOP plan.)

But it’s not just tax credits that would change, it’s likely premiums would too. Persons 60 or older who are buying on the individual market likely would see premiums rise. Under Obamacare, insurers could charge older adults up to 3 times as high as young adults. The GOP would change that ratio to 5-to-1.

For example, the CBO said that a 64-year-old with a $26,500 income would pay $1,700 in premiums in 2026 under Obamacare – but a whopping $14,600 under the GOP bill.

Most of them would go away. The GOP would eliminate the mandate penalty, fees on insurers and prescription drug manufacturers, taxes on the sales of certain medical devices, a surcharge on investment incomes and the 10 percent tax on indoor tanning services.

But, importantly, the GOP would keep the so-called Cadillac tax. Scheduled to begin in 2020, this Obamacare provision would impose an excise tax (paid by insurers and employers, not individuals) on health plans that cost more than $10,200 for individuals and $27,500 for families. The GOP would delay the phase-in by five years.

Supporters say the tax is a governor on health-care spending. Some Republicans, though, want to kill all the taxes imposed by Obamacare.

“My view is this: After spending seven years talking about the harm being caused by these taxes, it’s difficult to switch gears now and decide that they’re fine so long as they’re being used to pay for our healthcare bill,” Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) told The Hill.

The Perfect Workout

Dreaming of getting picture-perfect arms or iconic six-pack abs? With the help of fitness specialist Brian Dessart, we’ve selected a core group of exercises that target six key muscle groups and enlisted WWE wrestler Zack Ryder to show the proper technique for performing each move. Use these exercises to build your perfect workout plan.