Month: September 2021

COVID-19 & Boosters

Rehabbing Long Island’s Empty Storefronts

Newsday Live Author Series: A Chat with Stephanie Land

Gift of life, interrupted

Carissa Gordon’s hair fell out in clumps. Purplish bumps rose on her fingertips. Her eyes turned yellow with jaundice. She was rapidly dying at the age of 19.

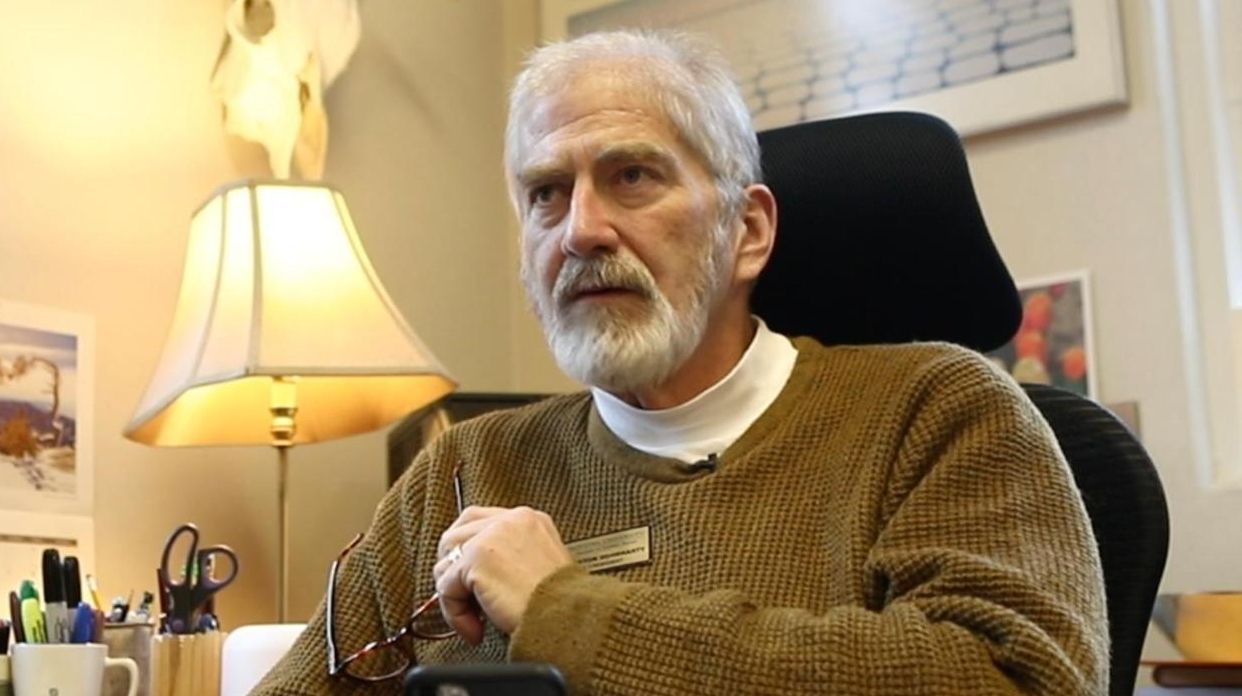

A liver transplant was Gordon’s only hope of surviving the sudden onset of an autoimmune disease. She was rushed to Northwell Health’s Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New Hyde Park, where Dr. Lewis Teperman found her comatose.

“I just remember coming in, evaluating and examining her and saying, ‘She’s going to die. She needs to get transplanted straight away,'” recalled Teperman, Northwell’s director of transplantation.

The crisis was especially extreme because Gordon’s liver failed in April last year as the COVID-19 pandemic overwhelmed hospitals on Long Island and across the region.

Among the consequences: Some of the nation’s most advanced transplant centers stopped, or severely curtailed, surgeries for patients requiring donated livers, kidneys, hearts and other organs to survive.

Aware that transplant candidates would likely die without new organs, physicians weighed whether they could, in fact, safely perform the complex operations amid the pandemic, as well as whether their hospitals could save more patients by diverting resources to caring for critically ill COVID patients. As later happened in hospitals across the country, transplant programs in New York largely shut down.

This little-noted interruption in a “gift of life” system lasted for two months, with profound consequences for some 10,000 patients in the downstate region, according to a Newsday analysis of health records and interviews with medical researchers, patients and their doctors.

Some transplant candidates lost their lives as organ donations plummeted.

Some died after doctors decided against using organs recovered from corpses because of fears that the organs could be infected by COVID-19.

Some came through transplants only to have COVID-19 fatally overwhelm their immune systems at approximately five times the rate experienced in the general population.

And, amid the tragedies, some happened into successful transplants by sheer luck.

Gordon, a Queensborough Community College student who dreams of opening a dance studio, was one of them.

As were Nathaniel Capelo, a 4-month-old infant whose liver failure caused bile to spout from his navel, and W. Houston Dougharty, a 59-year-old Hofstra University administrator who had dropped almost 150 pounds because he had lost kidney function.

“I was this close to losing my life,” Gordon said, holding two fingers nearly together. “Just by an inch, I got it saved.”

Medical experts say the repercussions of the two-month transplant shutdown represent a hidden toll of the coronavirus.

“Every time we couldn’t use an organ because of the risk of COVID-19, we knew that another life might be lost,” said Dr. Amy L. Friedman, chief medical officer of LiveOnNY, a nonprofit organization that coordinates transplants in the metropolitan New York area.

“I think collectively at least several hundred patients who needed transplants were affected. Either by getting COVID themselves and dying or becoming too sick to be transplanted.”

“We had a lot of patients who were waiting, got COVID and died,” said Dr. Sander Florman, director of The Recanati/Miller Transplantation Institute at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Manhattan, whose system includes Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside.

He estimated the losses in the New York area at “a few hundred” lives.

Physicians who perform organ transplants experience the satisfaction of extending lives, along with the frustration of losing patients while hoping in vain that suitable organs would become available. COVID inflicted more deaths than they had ever experienced.

“This is very hard for us,” Florman said. “We’re used to dealing with life and death, but in a pandemic where you don’t understand why it’s happening or how to treat it, it makes you feel a little more helpless than we normally feel.”

‘The virus was running us, instead of us running it.’

‘The virus was running us, instead of us running it.’

Even now, with vaccinations widely available, transplant doctors and patients face heightened challenges. On Aug. 12, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved giving added vaccinations to transplant recipients and other patients with weakened immune systems. Finding that recipients are “particularly at risk for severe disease” if infected by COVID, the agency OK’d three, rather than two, doses of the Pfizer-BioNtech or Moderna vaccines.

As coronavirus infections plunged the health care system into crisis last year, hospitals diverted transplant facilities and staff into caring for COVID patients; transplant units turned away healthy organ donors to protect them from hospital-based infections; and organs that might have been used for transplants were discarded.

“The virus was running us, instead of us running it,” recalled Northwell’s Teperman. “And we were learning how to cohabitate with the virus.”

In April and May last year, hospitals in New York State transplanted eight organs that had been donated by living individuals — compared with 113 in the same months in 2019.

“We felt it was not appropriate to bring a healthy person as a living donor into the hospital to donate a kidney until we had a better handle on how to manage it,” said Dr. Frank Darras, medical director of Stony Brook University Hospital’s transplant program. “So, for April and May, we postponed all of our scheduled living donor kidney transplants out of an abundance of caution.”

During the two-month pause, transplants of organs taken from deceased donors dropped by 46% in New York compared with the number performed in the same period in 2019 — from 312 to 170.

Some hospitals ceased transplants entirely. In 2019, for example, NYU Langone performed 24 organ transplants monthly from deceased donors and 13 per month from living donors. In April 2020, there were none at all.

“For people who need a liver transplant, lung transplant or heart transplant, there is no temporizing — unfortunately those patients need an organ when they really need it,” said NYU’s Dr. Nicole Ali, medical director of the kidney and pancreas transplant program at NYU Langone Health in Manhattan, which is associated with NYU Winthrop Hospital in Mineola.

“And for that two-and-a-half-month period where New York saw few organs, there was a tremendous impact for those patients. Many patients didn’t survive waiting for an organ that never came through.”

There were people who died, and they were waiting for the phone call and the phone call never came.

Joy Oppedisano president of Long Island Transplant Recipient International Organization

Estimating COVID-related deaths is an inexact science. Researchers have compared the 2020 toll with death rates in previous years among potential organ recipients.

Statewide, 590 patients died last year while waiting for transplants compared to 455 in 2019 — a 30% increase — according to state records.

A New York-Presbyterian Hospital network study found that 44 of its patients died waiting for kidneys between March and June last year, double the number in 2019. As another example, 12 people died last year while on Stony Brook University Hospital’s transplant waiting list — at least three of them as a result of COVID-19, hospital officials said.

Joy Oppedisano is president of Long Island Transplant Recipient International Organization, a 500-member support group. Speaking generally, she said:

“There were people who died, and they were waiting for the phone call and the phone call never came. They didn’t make it, and it was tragic.”

‘You can’t get any sicker as a human being.’

‘You can’t get any sicker as a human being.’

Nathaniel Capelo weighed only 3 pounds, 12 ounces, at birth, and he soon showed signs of severe liver disease. At the age of four months, his belly button expanded and leaked green bile.

“It looked like someone was spraying water out of a water gun,” remembered his mother, Alexandra Ramos, 25. “I was trying to put pressure on it to keep the liquid from coming out. But at that point, it was so much.”

Ramos and her fiance, Dennis Capelo, rushed Nathaniel from their home in Queens to Mount Sinai Medical Center in Manhattan. There, doctors told the couple that he would survive only with the help of a liver removed from the body of a deceased donor.

“I broke down in tears,” said Dennis, 28, “because you never know what’s going to happen. You knew how bad he was.”

Ramos and Capelo moved into an infection-free hospital room with their deathly sick baby. They waved at nurses from a distance.

“We weren’t allowed to interact, we had to stay in the room, so it was very isolating,” Capelo said.

Through hospital windows, they watched the white tents of a coronavirus field hospital pop up in Central Park. On their worst day, Nathaniel suffered a cardiac arrest.

Nathaniel Capelo, a 4-month-old infant whose liver failure caused bile to spout from his navel. Photo credit: Capelo family

“You can’t get any sicker as a human being,” said Florman, Nathaniel’s doctor. “A belly full of fluid. On a ventilator. The liver makes the clotting factor, so if the liver doesn’t work, you can’t stop bleeding. So, bleeding from the gums, the mouth — bleeding from everywhere. In fact, this child’s heart stopped. And the ICU was able to resuscitate the child, and literally able to bring the kid back to life.”

A few days later, a medical official informed Ramos and Capelo that she had found a transplant match in a murder victim in Maine. She said the donor had a history of heroin abuse but that wouldn’t affect Nathaniel.

“She went through the back story of the gentleman and asked if we wanted to accept or reject the donor,” Capelo remembered. “We didn’t even discuss it. Right away, we said yes.”

Florman’s team flew the donor’s liver to New York. Surgeons dissected it and then implanted a tiny portion inside Nathaniel. In a 12-hour operation, they connected the organ to his blood vessels and bile ducts. The remainder of the liver was transplanted into an adult recipient.

“We cut off the smallest anatomical piece that we could cut off,” Florman recalled. “It was technically at the extreme of what we can do.”

The intricate methods of transplanting an organ from one human into another has advanced from a medical rarity with short-lived successes to procedures that save thousands of lives every year.

A national network of doctors, hospitals, nonprofit groups and government agencies collaborate in systems that distribute organs to some of the more than 100,000 people nationally waiting for transplants.

There are never enough organs. In 2020, 107,000 patients were transplant candidates, but only 37,000 received the organs, according to the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Every day, 17 people died while hoping for the surgery. The gap between the demand for organs and their supply was greatest for kidneys.

Living donors have typically provided about 40% of all transplanted organs. Loved ones, friends and even generous strangers who answer public pleas for help can donate to specific recipients, provided their organs are medical matches.

Such donors often give one of their two kidneys, which remove wastes from the body, without suffering any long-term health consequences. Donors can also donate part of the liver, which regenerates in both the patient and donor, as well as parts of the lungs, pancreas and intestines.

The larger share of organs comes from the donors who have been declared brain dead, generally from natural causes or because of accidents or drug overdoses. Federal officials say 165 million people are registered donors nationally, but the organs of only 3 in 1,000 become usable after deaths.

Many donors are ruled out because they had suffered with diseases. Additionally, doctors must determine whether the organs of an individual donor are compatible for transplanting into a specific recipient.

Physicians study so-called matching factors such as body size and blood and tissue types. They also consider the severity of illnesses suffered by potential recipients, how long they have been on waiting lists and whether they will be available to accept new organs within hours.

The mortality risks from COVID is not nearly as high as the mortality risk for many of our patients waiting for a liver transplant. So, who are you supposed to take care of?

Dr. Sander Florman Mount Sinai Medical Center

Recipients must receive organs that are still functioning. After medical personnel determine that a donor’s brain activity has stopped, mechanical devices, such as ventilators, support the heart, lungs and other organs until they are removed from a body. Then, new machines keep the organs working while they are raced to recipients and transplanted.

When COVID patients filled hospitals, experts say demand for ventilators forced doctors to consider whether they might have to divert the scarce breathing machines away from maintaining dead donors on life support until their organs could be removed.

“These are very hard ethical questions,” Mt. Sinai’s Florman explained. “Remember, the mortality risk from COVID is not nearly as high as the mortality risk for many of our patients waiting for a liver transplant. So, who are you supposed to take care of?”

That problem dogged the staff of LiveOnNY.

“If we had a potential organ donor, I’d pick up the phone and reach out to the leader of that hospital and say, ‘I know you’re really tight for ventilators, but we have a potential donor. Can we please keep this patient on a ventilator for another day or two while we get the evaluation of the donor’s organs?'” medical director Friedman recalled.

‘You think, ‘What if this thing really goes south…”

‘You think, ‘What if this thing really goes south…”

In the throes of kidney failure, W. Houston Dougharty lived under the shadow of death while working as Hofstra University vice president for student affairs. Then, doctors at NYU Langone reported that someone — he didn’t know the name — had offered to donate a kidney and, possibly, was an ideal match.

Dougharty shared the news with former student Reba Putorti, who came to visit after learning of his plight via social media.

“And I just looked at him and said ‘that person is me,'” Putorti recalled. “The tears flowed and there was silence for about a minute. And he was in awe and said, ‘Really?'”

Putorti, 27, said she shared one of her two kidneys because she considered Dougharty a mentor who helped guide her into a career as a college administrator.

“When someone needs help, you help them out,” she explained.

Dougharty and Putorti planned to undergo successive surgeries in NYU Langone’s Manhattan transplant unit — one surgery removing Putorti’s kidney, the next implanting the organ into Dougharty.

Then came COVID. NYU Langone stopped performing transplants.

“We really had to think about whether it was safe to do transplants,” recalled Ali. “So, things across the state came to a screeching halt.”

Doctors confronted unanswerable questions.

“It was a very tenuous time because if he wound up needing dialysis before we can get him transplanted — and he winds up going on dialysis at a dialysis center — will that make him much more at risk of getting COVID?” Ali said.

“The patients who are on dialysis have a much greater chance of death than the general population. If he got COVID, would he be well enough to get transplanted later on?”

The shutdown sent tremors through Dougharty’s family.

“It was really scary,” recalled his wife, Kimberly, who was found not to be an ideal match. “You think, ‘What if this thing really goes south and he’s not able to get the transplant, or it’s not safe for Reba?'”

Dougharty’s body continued to weaken over the next three months. He stayed in touch with Putorti by text messages with emoji.

“Reba — what can I say? We are in awe of your generosity and concern. Can’t really express our appreciation. We will be in touch as I learn more about the timing…,” Dougharty wrote, using an angel symbol.

“You’re my inspiration and the reason I got into this field, the greatest mentor, and amazing person. It’s the least I could do! Thank you for everything you’ve done for me,” Putorti replied, with a heart.

In June 2020, NYU Langone resumed transplants. But hospitals ruled out transplanting organs from donors with COVID-19 histories for fear of introducing infections. (Since then, some surgeons will consider such organs if the donors are symptom-free).

“The first and most important test that they were going to do was to see if I had the COVID-19 antibodies,” Putorti recalled. “And if I did, I couldn’t be a donor anymore.”

Finally, Dougharty received Putorti’s kidney.

“It was such a blessing and miracle when they reopened and we were able to slip in there,” Dougharty said.

The hope generated for transplant recipients proved to be accompanied by a mortal threat.

Drugs that prevent immune systems from rejecting new organs also suppress the body’s ability to fight infections by a virus like COVID-19.

Through the end of March this year, 2,042 transplant recipients had tested positive and 309 had died. Their COVID mortality rate of 15% was five times higher than experienced by New York State’s general population.

Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx stopped kidney transplantation in April last year after the deaths of 10 out of 36 recipients stricken with COVID-19. These patients were at “high risk,” researchers concluded, because of suppressed immune systems and underlying health problems.

Recalling his own experiences in the Northwell system, Teperman said:

“I had one liver patient who I had worked with for 25 years and he wound up dying from COVID. … In the transplant population, when it infects and you’re hospitalized, you have a very high mortality.”

Similar deaths may mount.

“We haven’t been able to quantify the true impact that COVID has had on the waiting list because we still have patients dying,” NYU Langone’s Dr. Ali said in an interview earlier this year.

“People who were transplanted and got COVID after, one in four of them didn’t survive — that’s a really painful statistic. To think of the father who got a kidney from his son, a couple of months before he got COVID, and didn’t survive. To the patients who we tried everything and couldn’t make it better, those are really mentally taxing and sometimes you feel it physically.”

The threat continues. Transplant recipients like Hofstra’s Dougharty are discovering that COVID-19 vaccinations may not protect them as effectively as they do most people.

Transplant medications are designed to prevent the body from rejecting organs. A Johns Hopkins Medicine study found that the drugs appeared to blunt COVID vaccinations. The researchers later reported that an extra vaccine dose might improve COVID-19 protection.

Dougharty participated in the study. He said he was “crushed” by the initial findings but came around to viewing them as a “wrinkle” in his recovery. He’s encouraged by research showing an extra vaccine dose can improve COVID-19 protection and said he hopes to get his third shot soon.

“Except for when I am at home or alone in my office, I double-mask all the time,” he said. “When I do socialize, I only do so outdoors. I have turned down many invitations to indoor events. I will continue to do so until the docs at Hopkins, NYU or elsewhere figure out how the majority of us transplantees can be protected.”

‘She happened to have this at the worst time in world history.’

‘She happened to have this at the worst time in world history.’

Wai Fong Leung and Ramon Garcia were elated after donated kidneys saved their lives.

Leung’s surgery on March 14, 2020, was one of the last performed at Manhattan’s NYU Langone Medical Center before the coronavirus halted transplants.

“She felt she’d won the lottery,” said her daughter, Jennifer Leung. “Despite this crazy wave of virus and COVID happening, she felt she was so lucky.”

Weeks later, the coronavirus infected Leung, a 70-year-old retiree, at her home in Wantagh. She again fought for her life, this time with her immune system weakened by drugs used to stop her body from rejecting the kidney.

Leung immigrated from Hong Kong as a young adult. She met her future husband, Paul, who was then an engineering student, in Astoria, Queens. Once married, the couple moved in the 1980s to Levittown and then to Wantagh, where Jennifer and her brother, Chris, attended school.

Commuting to the city, Leung worked as an administrative assistant. After she turned 60, a genetically based condition called polycystic kidney disease slowly caused her kidneys to stop functioning properly. To survive, she would need dialysis to cleanse her blood of wastes — or undergo a kidney transplant.

Doctors told Leung that she could speed the search for an organ if she accepted a kidney from a deceased donor who had been infected with hepatitis C, a virus that can cause liver damage. Medical experts accept such donors in a trade-off between fatal renal failure and the risks of a disease that can be managed with medications.

“The doctor said you don’t want to defer too many chances of a donor becoming available,” Jennifer said, referring to her mother. “That was instilled in her brain — don’t defer anything. Take the chance that you have because this chance came out of the blue and so quick, before she even started dialysis. I think she felt, ‘This is a magical opportunity, let me jump on it without any hesitation.'”

Surgeons successfully implanted the kidney of a 35-year-old man who had died of a drug overdose. Leung recuperated at home. She and Paul wore masks and slept and watched television in different rooms to minimize the chance of COVID infection. Paul ventured out only occasionally to purchase groceries.

The virus crept in. Leung spent her last week hospitalized in NYU Langone. She died there on May 29 this year, at age 70, leaving her family to wonder whether she would still be with them if she had relied on dialysis while hoping that another kidney would become available after the pandemic ebbed.

“She happened to have this at the worst time in world history, to get this operation,” said her son, Chris, thinking back to Leung’s surgery in Manhattan. “If she’d been in Long Island all the time, she’d be alive today.”

‘I couldn’t say goodbye …’

‘I couldn’t say goodbye …’

Ramon Garcia similarly lived in fear of COVID-19 after his second transplant.

Garcia had battled kidney disease from the age of 5, when he developed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, a condition that harms a kidney’s ability to filter blood. He grew up playing soccer and baseball, participated in the Boy Scouts and graduated from Amityville High School near the top of his class.

In 2008, at the age of 17, Garcia began dialysis. Two months later, Mount Sinai surgeons implanted the kidney of a 19-year-old who had been killed by a car. The organ functioned well until 2015, when Garcia again required dialysis, three sessions a week, two hours each.

He scheduled treatments in the morning, attended Farmingdale State College classes in the afternoon and earned a business management degree in 2019.

Shortly before Garcia received his degree, Northwell doctors determined he needed his second transplant. An organ became available from the body of a deceased donor who had been infected with hepatitis C. Garcia’s mother, Fanny, remembers conversations with his doctors and transplant network officials.

“They said he needed a transplant, but it would be eight years at least for him to get a kidney,” she said. “Then they called and said that they had a kidney with hepatitis C. The doctors said there was no problem, ‘We can treat hepatitis C — take it.’ And he did it.”

Surgeons implanted the organ in November 2019. Garcia talked about opening a restaurant and hiring his mother as the chef. He spent months at home. In his room, he kept a letter of thanks.

“Dear God, Thanks for my Health, and my graduation, and for healing me. This year I want to focus on my creativity and turn that into a business and use that same energy for my other entrepreneurial endeavors.”

Then, Fanny, her youngest son and Garcia’s stepfather contracted the coronavirus and recovered. On Dec. 29, 2020, Ramon Garcia tested positive and was admitted to Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center in West Islip. His mother never saw him in person again. He told her by telephone that he expected to survive and come home soon. Less than two weeks later, Garcia died at the age of 20.

His mother’s pain is measured in tears and mementos.

“I couldn’t say goodbye,” she sobbed. “I couldn’t touch my son. Give him a hug. This is what killed me.”

Outside the family’s Lindenhurst home, Garcia’s brother Miguel reflected on Ramon’s gamble with undergoing a transplant during the COVID-19 pandemic: “He understood that, at the end of the day, if he got it, it was over for him.”

More than a year after their transplants, new organs sustain the lives of Clarissa Gordon, Nathaniel Capelo and W. Houston Dougharty.

Happenstances profoundly broke their way.

Each escaped coronavirus infection that would have ruled them out for a transplant.

Each benefited from advanced medical care in a time of dire scarcity.

Each overcame a life-threatening crisis after suitable organs became available at the right moment, two of them at the cost of lives.

Gordon’s donor was a 27-year-old Massachusetts woman who had died in a car accident. Her kidney was flown to New York. An ambulance transported Gordon from Northwell on Long Island to Mount Sinai in Manhattan, which had equipped an unused recovery room for a limited number of do-or-die transplants.

‘I was grateful to get her liver’

‘I was grateful to get her liver’

“If any one of these things didn’t work, she probably wouldn’t have [survived],” Florman said. “She plain got lucky.”

Now, Gordon hopes to start her own hip-hop dance studio and thinks of becoming a nurse. She bears a long scar on her stomach and struggles to find the words to thank the family of her deceased donor.

“It’s hard because she lost her life and I was grateful to get her liver,” Gordon said. “But it’s kind of hard stating that in a letter. I really don’t know what to say. I’m not good with writing letters. I’m so sad, I don’t know what to say.”

W. Houston Dougharty has returned to mentoring Hofstra University students like Reba Putorti, whose kidney proved to be an unforgettable gift. Facing death during the transplant shutdown deepened his sense of the fragility of life.

“It really gets you in touch with your mortality,” Dougharty said.

As he nears his second birthday, Nathaniel Capelo is home with his parents — and doubly fortunate for having weathered a coronavirus infection. He has grown into a scampering toddler.

“The doctors are still monitoring him and stuff. But all his labs are good,” said his father, Dennis. “He’s developing so fast since he came out of the hospital.”

Only Nathaniel’s smile is infectious.

Reporter: Thomas Maier

Editor: Arthur Browne

Video and photo: Reece T. Williams, Chris Ware

Video editor: Jeffrey Basinger

Writer, studio production Arthur Mochi Jr.

Studio graphics: Gregory Stevens

Video production: Basinger, Robert Cassidy, Maier

Digital producer: Heather Doyle

Digital design/UX: James Stewart

Social media editor: Gabriella Vukelić

Print design: Seth Mates

QA: Sumeet Kaur