Category: Long Island

White Zone

No house hunter asked specifically to live in three Long Island communities where white residents dominate the population – but seven real estate agents specifically suggested them almost exclusively to white potential buyers during Newsday’s investigation.

Merrick, Levittown and Rockville Centre in Nassau County emerged in the testing as places that these agents overwhelmingly chose for the white customers but not for their matching, paired minority home seekers. The makeup of the communities ranges from 75 percent white to 88 percent white.

The agents’ choices matched the demographics of the towns: The seven gave their white customers 13 times more listings in the communities than they provided to matching minority buyers. Two suggested homes there only to their white customers.

In all seven tests, Newsday’s two fair-housing consultants – Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, and Robert Schwemm, professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law – independently detected evidence of steering.

Real estate agents engage in steering, which is outlawed under the Fair Housing Act, by encouraging members of racial or ethnic groups to consider particular neighborhoods and discouraging others based on race, ethnicity or religion.

While meeting with the seven agents, Newsday testers – one white, the other black, Hispanic or Asian – posed as first-time buyers who were considering a general location rather than a precise neighborhood.

For example, they asked for help finding $600,000 houses within an hour’s commute to Manhattan, $450,000 houses within 30 minutes of Garden City or $500,000 properties within a half-hour of Bethpage.

Following protocols used in paired testing by government-sponsored fair housing enforcement investigations, the testers were matched by qualities such as gender, age and education and presented comparable personal profiles and home-search criteria.

The territories covered by the requests gave the agents authority to recommend houses in communities whose demographics ranged widely. Those varied from 97 percent black and Hispanic Roosevelt to 23 percent Asian Hicksville to 88 percent white Merrick.

When white and minority buyers are matched and make comparable requests for help finding houses, agents should, in theory, give them roughly similar listings to consider in comparable places. Wide disparities could show evidence of racial or ethnic steering.

All things being equal, a map of the listings an agent suggested to paired testers would distribute the listings evenly across an area.

Agents did, in fact, recommend houses to white, black, Hispanic and Asian testers at similar levels in some communities.

Consider, for example, Bellmore, Wantagh, Seaford, Massapequa and Massapequa Park, five communities that stretch six miles along the South Shore. Their populations are 85 percent to 90 percent white. All told, 22 agents located 616 listings in those communities, distributing the listings between white and minority buyers in roughly similar numbers.

As one example, 12 agents suggested 114 Wantagh listings, giving 57 percent to white customers and 43 percent to matching minority buyers. As another, 14 agents suggested 273 Massapequa listings, giving 42 percent to white customers and 58 percent to matching minority buyers.

Coldwell Banker Residential agent Robert Stiles suggested comparable numbers of homes in the South Shore communities to white and minority testers when the testers, one white, the other Asian, sought his help finding $450,000 homes within a half-hour of Hempstead. Stiles did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

Based in Bellmore, Stiles recommended two listings in Wantagh to each customer, while also pointing out three Bellmore listings to the white customer and two to the Asian house hunter.

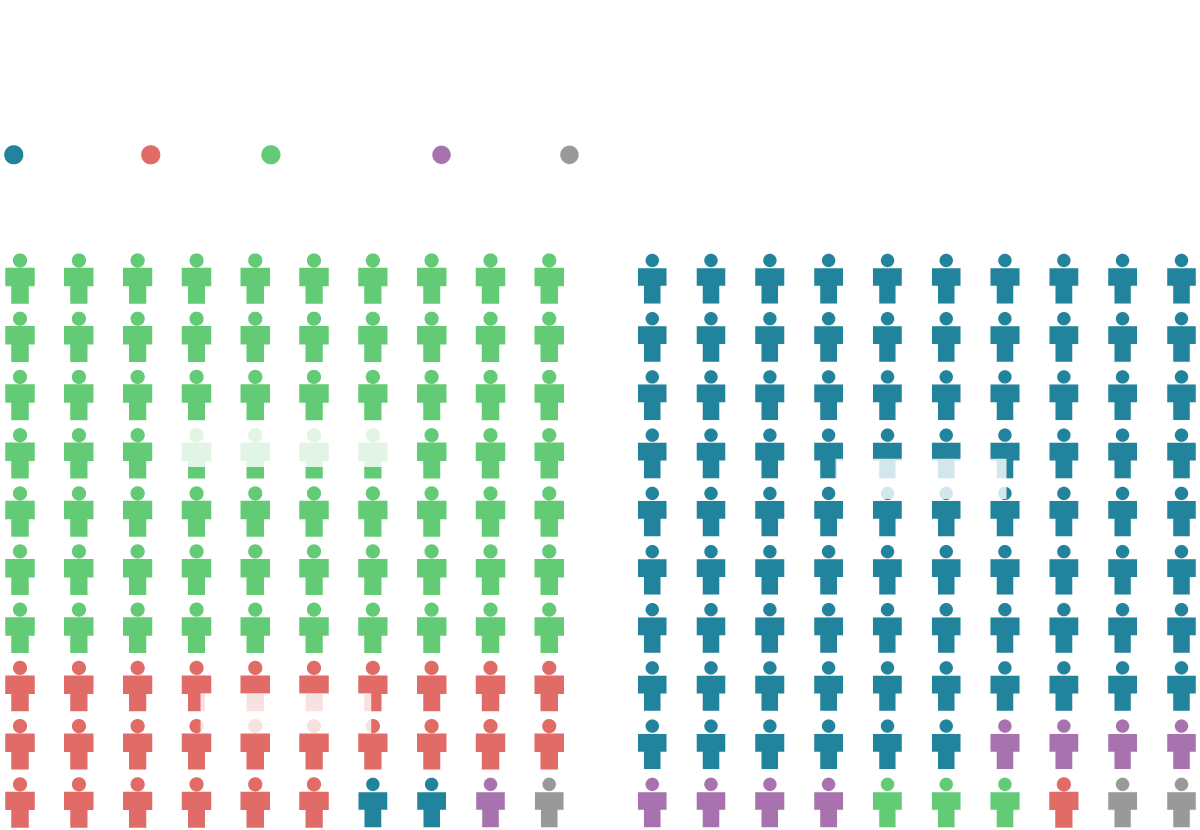

In seven tests:Agents placed 94% of the listings for Merrick, Levittown and Rockville Centre with white house hunters

In contrast, seven agents provided listings that favored white over minority house hunters in Merrick, Levittown and Rockville Centre.

Separated by as few as five miles and as many as 12, Merrick, Rockville Centre and Levittown sit at the points of a triangle in the middle of Long Island’s South Shore.

The three have been solid places to invest in housing: Home values appreciated at least 3.4 percent per year since 1990, a rate faster than experienced in two-thirds of Long Island’s communities, according to a Newsday analysis of the Federal Housing Finance Agency price index.

Although similar in demographics, they have distinct characters and histories.

Rockville Centre offers a close-in commute to New York City on the Long Island Rail Road’s Babylon branch and is home to the imposing edifice of St. Agnes Cathedral, the seat of Long Island’s Roman Catholic diocese. Single-family houses, ranging from Capes to rambling Tudors, line leafy streets. The school district touts that 91 percent of the 2018 high school graduates earned a Regents diploma with advanced designation.

Almost one in five of the district’s students is black or Hispanic. While the minority children are dispersed throughout the schools, white and minority families live largely in separate areas. Most black residents are clustered in attached housing in a corner of the village close to the train tracks, a legacy of bitterly fought, so-called urban renewal that bulldozed a historic black settlement a half century ago.

Merrick is a prosperous community that boasts highly rated schools, access to the South Shore bayfront and a drive of less than 10 minutes to Jones Beach. Its median household income is almost $140,000 – roughly one-third higher than the Nassau County median. A significant Jewish population supports four synagogues, and there is a thriving Catholic parish.

While Merrick is largely homogenous, with a population that is 88 percent white, its western boundary, the Meadowbrook Parkway, sits like a barrier to two overwhelmingly minority communities, Roosevelt and Freeport.

To the northeast, the concrete slabs on which William Levitt built 17,000 tract houses on farmland in the late 1940s that became Levittown formed a crucial foundation for the construction of suburban Long Island.

His legacy today is a place in which many homes have been expanded, families stay through generations and the community takes pride in the strength of its schools, the bustle of its library and recreation facilities that include eight pools.

Levitt’s legacy also includes Levittown’s identity as an overwhelmingly white community due to covenants barring blacks that Levitt wrote into his initial deeds. While diversity has increased, with growing Hispanic and Asian representations, Levittown’s share of African Americans still hovers at roughly 1 percent.

In the seven tests cited as showing evidence of steering into and away from Merrick, Levittown and Rockville Centre, agents recommended 156 listings in the three communities – placing 93 percent of the listings with white house hunters.

An additional 13 agents also selected listings in Merrick, Levittown and Rockville Centre. Although these agents directed 71 percent of these listings to white buyers, Newsday’s consultants said differences in the placement of listings given to white and minority testers were not large enough to show patterns of steering.

Cumulatively, the 20 agents provided 82 percent of their Merrick, Levittown and Rockville Centre listings to white home buyers – a figure roughly in line with the white makeup of the three towns.

Two paired tests conducted over a three-month period in 2017 illustrate the imbalances that came into play in Levittown and Merrick as agents recommended homes for white and Hispanic buyers in both communities.

Hispanic tester

Sent to some majority white areas but not Merrick, Levittown

White tester

Sent to mostly white areas including Merrick, LevittownIn one of the tests, white and Hispanic buyers asked Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage agent Maria Vermeulen for help finding $475,000 houses within 30 minutes of Hempstead.

Vermeulen, who was based in Massapequa Park, recommended 28 homes in Levittown and seven homes in Merrick to the white buyer. She offered no homes in either community to the Hispanic buyer.

Instead, she pointed the Hispanic buyer east to Wantagh, Seaford and Massapequa, which are among the predominantly white communities where agents provided roughly equal listings to white and minority testers. She also suggested homes there to the white buyer.

Based on information provided by Newsday, fair housing consultant Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, concluded:

“The selection of home listings by the agent raises concern about possible steering. Although the agent selected many home listings for both testers in predominantly white areas, only the white tester received listings in the predominantly white areas of Levittown and Merrick.”

Consultant Robert Schwemm found that the 7-0 gap in the listings that Vermeulen provided in Merrick to the white and Hispanic testers “is large enough to make out a case of pro-white steering to Merrick.” Similarly, he judged that the 28-0 difference in Levittown “is large enough to make out a case of pro-white steering to Levittown.”

There, he added: “The conduct seems to violate the Fair Housing Act vis-a-vis Levittown, potentially producing claims by both the minority testers and the town.”

Newsday sent Vermeulen a letter detailing the findings of the tests, invited her by letter and email to view video recordings of her interactions with testers and requested an interview. She did not respond to the letter and email or to a later telephone message seeking comment.

Newsday presented its findings by letter to Charlie Young, president and chief executive officer of Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage. The letter covered the actions of Vermeulen and additional Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage agents.

The company’s national director of public relations, Roni Boyles, wrote in an emailed statement:

“Incidents reported by Newsday that are alleged to have occurred more than two years ago are completely contrary to our long term commitment and dedication to supporting and maintaining all aspects of fair and equitable housing.

“Upholding the Fair Housing Act remains one of our highest priorities, and we expect the same level of commitment of the more than 750 independent real estate salespersons who chose to affiliate with Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage on Long Island. We take this matter seriously and have addressed the alleged incidents with the salespersons.”

Coldwell Banker declined to discuss the company’s responses to specific cases.

Hispanic tester

Offered no listings in mostly white Levittown

White tester

Received 22 listings in mostly white LevittownIn the second test that entailed Merrick and Levittown listings, white and Hispanic house hunters relied on Century 21 agent Gina Minutoli for assistance in seeking $500,000 homes within an hour of Manhattan.

The agent, based in East Meadow, gave the white buyer 22 choices in Levittown and 19 in Merrick while providing the Hispanic customers with no Levittown possibilities, plus three Merrick listings to consider.

Instead, Minutoli directed the Hispanic buyer to Bellmore, Wantagh, East Meadow and Westbury, while also providing the white buyer with choices in those areas.

Freiberg concluded that the selection of listings in both Levittown and Merrick “raises concerns about possible steering.”

Schwemm saw “pro-white steering” to Merrick and Levittown in both tests and said more generally, “These tests taken together show a clear pattern of pro-white steering to Merrick.”

Newsday detailed the findings to Minutoli by letter, invited her by letter and email to view video recordings of her interactions with testers and requested an interview. She, along with a fellow agent and branch manager reviewed Newsday’s video recording and listings maps, but none of them commented at the time.

More than a month later when Newsday reached out to her for a comment, Minutoli said: “I had gotten an email from someone. It’s extremely unfounded. It’s so untrue. I was told by everyone not to comment. It’s sad, that’s all I’m going to say. It’s so not me.”

Similar imbalances in listings offered in Levittown in one test (18 for a white buyer, three for a black buyer) and in two tests in Merrick (six for a white buyer, two for a black buyer; and 15 for a white buyer, two for a Hispanic buyer) prompted Freiberg and Schwemm to detect possible evidence of pro-white steering.

Black tester

White tester

A single agent, who showed no evidence of providing disparate treatment or steering, accounted for two-thirds of the listings provided to minority house hunters in Levittown. Ethiel Melicio of Century 21 Catapano Homes gave 60 Levittown listings to his white customer, while also providing a substantial number – 23 – to his black client in searches for $500,000 homes within a half-hour of Bethpage.

Newsday presented its findings by letter to Michael Miedler, president and chief executive officer of Century 21 Real Estate LLC. The letter covered the actions of Minutoli, Melicio and additional Century 21 agents. Miedler and Melicio did not respond to requests for comment.

Collectively, six agents recommended homes to buyers in Rockville Centre. Two of the tests showed evidence of steering, the consultants said.

Black tester

Offered no listings in Garden City, Rockville Centre

White tester

Sent to mostly white Garden City, Rockville CentreIn one of those tests, black and white house hunters asked Coach Realtors agent Mary Weille to recommend homes priced at up to $600,000 in neighborhoods within an hour commute of Manhattan.

Weille stressed to both buyers that their budgets would not stretch far in her home base of Garden City because most homes were more expensive than $600,000. She suggested five house listings in sections of Rockville Centre that averaged 83 percent white to the white buyer.

Weille did not mention Rockville Centre to the black customer and offered no home possibilities there.

According to Zillow, more than two dozen Rockville Centre houses were listed as available within the price range on the date when the black customer met with Weille.

Black tester

Offered one listing in Rockville Centre, none in Merrick

White tester

Offered 18 listings in Rockville Centre, 14 in MerrickIn the second test cited as showing evidence of steering in Rockville Centre, Coach Realtors agent Jayne McGratty Armstrong responded to white and black buyers seeking $600,000 houses within an hour of Manhattan. She offered 18 houses there to the white buyer and only one to the black customer. At the same time, she provided the white buyer with 14 choices in Merrick and none to the black customer.

Both McGratty and Weille work for Coach Realtors. Newsday detailed the test findings by letter, invited them by letter and email to view video recordings of their interactions with testers and requested interviews. Neither responded.

Three leaders of Coach Realtors – Georgianna Finn, the firm’s founder, Lawrence Finn, a company owner, and Whitney LaCosta, principal and broker of record – viewed Newsday’s video recordings and listings maps. They declined to comment.

– With Rachelle Blidner, Bart Jones, Deborah S. Morris and Carol Polsky

Watch videos of the testsSources: Demographic data in maps from Census Bureau 2016 American Community Survey five-year estimates.

Hispanics face hurdles as population grows

Pedro Jimenez expected to find evidence of some discrimination as a Hispanic searching for a home on Long Island. He found more than he imagined as a member of the Island’s largest minority group.

Jimenez asked eight real estate agents for help buying houses as a paired tester in Newsday’s investigation of discrimination in real estate sales. Five of the eight tests produced evidence that agents had subjected Jimenez to unequal treatment when compared with his white counterparts.

“It is alarming. It is crazy,” he said. “It’s 2018, I cannot stress that enough – this is 50 years after the civil rights marches. I remember all sorts of people saying, well, we’re post racial, we voted a black president. No, we’re not. Obviously, we are not.”

Jimenez, 45, is a computer and internet professional who was born in the Dominican Republic.

As a boy of 5, he followed his mother to immigrate legally to the United States. He grew up in the Corona section of Queens, attended New York City public schools and helped his mother earn income by making belts in the family’s apartment.

Jimenez also remembers that the social surroundings taught him to distinguish between light-skinned and dark-skinned fellow Hispanics, those of darker tones being looked down upon.

The milieu also included attitudes toward women and gays that he long ago grew to consider backwards.

“I’ve been everything. I’ve been the misogynist. I’ve been the racist. I’ve been the homophobe. Over time I just came to learn almost in evolutionary steps there is no basis for those things,” Jimenez said. “You don’t know these people, how can you cast this light on people you don’t know? And not only that, but by having this view I am causing this suffering.”

That evolution, Jimenez believes, outpaced the attitudes of real estate agents he encountered as an undercover tester.

“What this says to the Latino population is that, clearly, you’re going to be steered, especially if you leave yourself at the mercy of the agent,” he said.

Latinos compose 18 percent of the Island’s population, according to 2017 census estimates, followed by blacks at 9 percent and Asians at nearly 7 percent. They are spread widely, with 90 percent of the population living in 120 of the Island’s 291 communities. The United States Census Bureau defines Hispanics and Latinos as people of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race.

Jimenez was one of five Hispanic testers who went undercover in Newsday’s investigation.

They engaged with agents representing 12 of the Island’s largest brokering firms in offices located from Massapequa Park, Brentwood and East Hampton on the South Shore to Great Neck and Northport on the North Shore. Using aliases with Hispanic surnames, they said they were looking for houses with prices that ranged from $400,000 to $3 million.

All told, Newsday’s:five Hispanic testers met evidence of disparate treatment

39% of the time

Jimenez, Ashley Creary, Nana Ponceleon, Liza Colpa and Jesus Rivera went house hunting 31 times while paired with matching white testers. Twelve of the tests showed evidence that agents:

- Provided the group 12 percent fewer listings than the white buyers in those tests, with the gap larger in the overwhelmingly white communities of Rockville Centre, Oceanside, Roslyn, Levittown, Merrick and Kings Park. There, the agents gave white testers seven times more homes to consider than they provided to matching Hispanic testers.

- Focused Hispanic testers on houses in 18 census tracts in the Town of Huntington that took in the downtown area, then stretched north to Halesite and south to Huntington Station, South Huntington and West Hills. They picked listings in these areas for Hispanic testers at double the rate they did for white buyers. Eleven of the 18 tracts show growing Hispanic populations.

- In one case, imposed more stringent requirements on a Hispanic tester than a white buyer, amounting to a denial of equal service, according to evaluations by Newsday’s fair housing consultants.

Following are three case histories showing evidence that Hispanic house hunters experienced disparate treatment, along with the findings of Newsday’s fair housing consultants Fred Freiberg and Robert Schwemm.

The opinions of Freiberg and Schwemm are based on data provided by Newsday. Their judgments are not legal conclusions.

The case histories each include the experts’ findings, and responses of agents and the companies they represent.

Agent gives fewer listings to Hispanic buyer, directs him to more diverse communities

Richard Helling and Pedro Jimenez presented identical requests to Charles Rutenberg agent Maurice Johnson three weeks apart in the spring of 2017: As first-time house hunters who were new to Long Island, each sought help finding a $500,000 home within 20 minutes of Garden City.

Johnson mentioned 12 communities as possibilities to Helling, who is white, and suggested that he might like to live in waterfront communities.

While meeting with Jimenez, who is Hispanic, Johnson offered no list of communities and did not mention the waterfront.

Hispanic Tester:

Pedro Jimenez

Listings Given:

100

Census Tracts:

56% white on average

White Tester:

Richard Helling

Listings Given:

147

Census Tracts:

64% white on average

Johnson told Helling that Half Hollow Hills, at the time 59 percent white, was a “good school district” and expressed regret that, in his view, the law would bar him from warning a customer away from overwhelmingly minority Wyandanch, where, he said, “the school district is underperforming.”

His listings gave Helling almost 50 percent more home choices to consider than Jimenez – 147 to 100.

Comparable numbers of similarly priced homes were on the market in the area at the times of the two tests, according to Zillow, the internet-based house-listing service. Zillow drew the data for Newsday at no cost from the Multiple Listing Service of Long Island, the online network used by agents to keep up with properties for sale.

The house selections also directed Helling to tracts whose white populations were on average 8 percentage points higher than in the tracts to which he pointed Jimenez: 64 percent white to 56 percent white.

The listings map shows that he pointed Helling toward:

- 86 percent white Oceanside with 16 listings, offering none there to Jimenez.

- 86 percent white Merrick and North Merrick with 19 listings, recommending only two there to Jimenez.

- 66 percent white Mineola with four listings, providing none there to Jimenez.

At the same time, Johnson directed Jimenez toward:

- 85 percent minority Elmont with seven listings, giving none there to Helling.

- 66 percent minority Baldwin and North Baldwin, as well as 51 percent minority Baldwin Harbor with 15 listings, offering Helling five in Baldwin and Baldwin Harbor.

- 81 percent minority Malverne School District with 11 listings, recommending none there to Helling.

Experts’ Findings

Freiberg: The agent’s conduct on this test raises a concern about possible racial steering. The agent told the white tester about a school district that is good, Half Hollow Hills (59 percent white), and states that he is not allowed to tell buyers that an adjacent school district, Wyandanch (1 percent white), is under-performing. He does not provide these examples to the Hispanic tester but refers both testers to greatschools.org to obtain more information about schools. Most of the home listings the agent selected in the predominantly white communities of Merrick, Island Park, Rockville Center and Oceanside were given to the white tester. Most of the home listings the agent selected in the predominantly minority communities of Baldwin and Elmont were given to the Hispanic tester, as well as the Malverne School District.

Schwemm: Lots of apparent steering here.

From west to east, the agent seems to have provided four differing groups of listings:

The agent located the most listings for the Hispanic tester in the far westerly area, particularly to the north with highly diverse schools.

In the second westerly area, the agent placed a few Hispanic listings, in the most diverse parts, while placing mostly white listings in the least diverse school districts.

The second most easterly area shows few Hispanics listings with mostly white listings in the least diverse school districts.

In the most easterly area, the agent placed the Hispanic tester’s listings in the north and the white tester’s listings in the south, where schools are less diverse.

Agent’s Response

Informed of Newsday’s findings, Johnson did not respond personally. His lawyer, R. Joseph Coryat, reviewed both the video recordings of Johnson’s meetings with testers and the maps of where he placed listings for each tester. Newsday provided Coryat copies of all communications between the testers and Johnson.

He accused Newsday of unfairly editing one of Johnson’s videos because the first 10 seconds of greeting between Johnson and a tester were trimmed to protect the privacy of unrelated third parties. Newsday gave Coryat a transcript of the trimmed section and invited him to view it. He never did so.

Newsday also sent Coryat specific questions about how Johnson selected the listings and provided excerpts of moments during the meetings that appeared to have been of interest to Coryat after he viewed the videos. He did not answer the questions.

Joseph Moshe, founder of Charles Rutenberg Realty, viewed Newsday’s recordings of three Charles Rutenberg agents, including Johnson. Subsequently, he offered no comments.

Agent points Hispanic buyer toward minority school districts, does opposite for white buyer

Seven months apart, Nana Ponceleon and Kimberly Larkin-Battista told Charles Rutenberg agent Stephanie Giordano that each had a school-age child and was seeking to buy a $400,000 house within 30 minutes of Brentwood.

Ponceleon is Hispanic from Venezuela. She used the alias Rita Viloria and said her husband was Luis. Larkin-Battista is white. She used the alias Karen Wally. Her husband’s name did not come up in the conversation.

Giordano advised each to research the quality of schools in communities where they might want to live and said she would provide a link to a helpful digital database.

The school districts in and around Brentwood varied in the makeup of their student bodies and educational performance. Comparing their high schools offers a picture.

Brentwood High School’s student population in 2018 was 83 percent Hispanic, 11 percent black, 4.2 percent white and 2 percent Asian. Twenty-one percent of the 1,500 graduates earned a Regents Diploma with Advanced Designation, signaling they had passed at least eight Regents exams, New York State Education Department statistics show.

In the adjoining district, Bay Shore Senior High School had 474 graduates, with 35 percent earning advanced designation diplomas. The high school’s demographics broke down as 43 percent Hispanic, 30 percent white, 21 percent black and 5 percent Asian, state statistics show.

To the north and east, two Sachem district high schools combined for the graduation of 1,106 students, with 59 percent earning advanced designation diplomas. State statistics show their full student bodies were approximately 77 percent white, 12 percent Hispanic, 8 percent Asian and 3 percent black. Closer to Brentwood is the Connetquot district, which in 2018 graduated 481 students, with 63 percent earning advanced designation diplomas. Its student body was 77 percent white, 14 percent Hispanic, 6 percent Asian and 2 percent black. After Ponceleon told Giordano that she worked close to the city, Giordano said that she would focus the house search narrowly. “In Brentwood Bay Shore areas – we’ll try to keep you around here,” she said, referring to two predominantly minority communities.

Hispanic Tester:

Nana Ponceleon

Listings Given:

76

Census Tracts:

65% white on average

White Tester:

Kimberly Larkin-Battista

Listings Given:

155

Census Tracts:

81% white on average

Although Ponceleon had told Giordano that distance was not an immediate concern, Giordano added: “Also, what – I don’t want to bring you any further out east because you travel to New York.”

While meeting with Larkin-Battista, who said that she worked as a teacher in Queens, Giordano recommended searching in areas other than Brentwood. Referring to Larkin-Battista’s husband, she said:

“If he’s in Brentwood, you’re gonna want to be in the – the surrounding areas.”

After telling Larkin-Battista “to really kind of zone in on” school ratings, she added, “the areas that could surround would be Bay Shore, Islip. You could even do Hauppauge.”

Giordano sent Ponceleon 74 listings. As she had indicated, she weighted them toward Brentwood and Bay Shore. The listings included 27 houses in Bay Shore, including nine in the Brentwood school district, and spread the rest farther east. They fell in tracts with populations that average 66 percent white.

In contrast, Giordano provided Larkin-Battista double the number of listings, 152, none in Bay Shore or the Brentwood school district. Instead, she distributed them as much as 14 miles to the east in predominantly white Farmingville. The tracts averaged 81 percent white. She offered Ponceleon no listings in Farmingville.

Based on school boundaries, Giordano’s 27 listings pointed only Ponceleon to the predominantly minority Brentwood and Bay Shore districts, where, respectively, 21 percent and 35 percent of the graduates earned advanced Regent’s designation diplomas in 2018.

Conversely, at 87 listings, Giordano offered Larkin-Battista nearly four times the opportunity she gave Ponceleon to consider houses in the predominantly white Sachem school district, which has two high schools, where a combined 59 percent of the graduates earned Advanced Regent’s designation diplomas. The proportion of listings was similar in the predominantly white Connetquot district, with 46 for Larkin-Battista and 12 for Ponceleon.

Overall, Giordano provided the white tester listings in areas that averaged 81 percent white, while giving the Hispanic tester listings in areas that averaged 66 percent white.

Drawing on data from the Multiple Listing Service of Long Island, the online network used by agents to keep up with properties for sale, Zillow computed that more than 300 homes were actively on the market up to a half hour from Brentwood on the dates of both tests, at prices within 10 percent of the requested cost.

Ponceleon and Larkin-Battista each said that they had seen no reason to question Giordano’s actions until after they had compared results.

“At the beginning it was like, oh, OK, and then when I thought about it I was like, hmmm. Same circumstances, same income, same requests, different result,” Ponceleon said. “Definitely, there is, in my mind there’s a bias there. It’s quite obvious, I guess. Because it’s not minute, the difference. It’s huge, in terms of number of listings, in terms of percentage of white population. It’s a big enough spread to say I was not given the same options.”

Larkin-Battista said she was taken aback both that Giordano had given her more home choices than she gave to Ponceleon and that the locations were often separate.

“It’s really upsetting to me that it could be that stark of a difference and just that people wouldn’t know,” Larkin-Battista said, highlighting that house hunters generally cannot evaluate how agents serve them compared with others.

Experts’ Findings

Frieberg: The agent’s comments to the white tester about Brentwood’s surrounding area coupled with the initial selection of home listings provided both testers suggests possible steering. The agent only provided listings in Brentwood and Bay Shore, both predominantly minority communities, to the Hispanic tester and the same agent only provided listings to the white tester in predominately white areas.

Schwemm: Overall, steering seems clear.

Most white listings are shown in eastern areas (particularly northern part) where less than half of the Hispanic listings are shown. The majority of Hispanic listings are shown in western, more diverse areas, where less than half of whites are shown.

Agent’s Response

After reviewing video of the two tests at Newsday, along with maps of the listings, Giordano vehemently denied any suggestion of disparate treatement based on race or ethnicity.

Her lawyer, Michael Janus, later wrote in an email that Giordano sends listings to clients by entering search criteria they provide into a computer system; that Giordano “is perplexed on how she would know the ethnic background of the tester since she never asked and never would have asked her what ethnicity she was, as this is illegal.”

“She has never refused to show in an area or ever hinted to a customer that one area would be better for them based on their race,” Janus said, adding that Giordano recommended houses to the Hispanic tester in Ronkonkoma, “which would be considered a higher demographic of white people.”

Joseph Moshe, founder of Charles Rutenberg Realty, viewed Newsday’s recordings of three Charles Rutenberg agents, including Giordano. Subsequently, he offered no comments.

Agent gives only white tester listings in predominantly white Roslyn

Posing as first-time home buyers, Pedro Jimenez and white counterpart Richard Helling met with Laffey Real Estate agents Diane Leyden and Neil Gortler less than a month apart in the spring of 2017.

Leyden and Gortler broker home sales around the Great Neck and Port Washington peninsulas. On her Laffey web page, Leyden describes herself as having “a unique and formidable presence within the Great Neck community.”

The nearby localities include Manhasset and Roslyn, where median home sales prices hover around $1 million. The racial and ethnic compositions of some areas have changed rapidly, notably with the arrival of Asian households.

The population of Manhasset Hills, for example, shifted from 67 percent white in 2010 to 45 percent white seven years later, with Asians making up 43 percent of the community, Hispanics 11 percent and blacks zero in 2017.

Hispanic Tester:

Pedro Jimenez

Listings Given:

27

Census Tracts:

69% white on average

White Tester:

Richard Helling

Listings Given:

31

Census Tracts:

76% white on average

Before Jimenez had time to present his profile – $1.5-million house, $300,000 down payment, $340,000 annual family income – to the agents, Leyden told him:

“Basically, what I suggest first-time home buyers to do is figure out more or less what their monthly payments – what their living expense so they’re not – so they’re not eating spaghetti, tuna fish, and they can – can go to the movies and take their kids to, you know, a ballgame once in a while.”

She offered Helling no similar counseling.

Instead, she offered Helling – and not Jimenez – advice on shopping for a house in a diversifying area.

Saying she was not speaking in “a negative way” about his lack of knowledge of the area, Leyden told Helling to research community makeups “because you might be more comfortable in a certain demographic area that isn’t heavily one way or another in terms of people.”

“Do you want your kids to be in school with kids that they relate to?” she asked, adding, “I would assume, as well as a diverse population.”

Leyden pressed Helling to look up community demographics on Google, indicating that she could run afoul of fair-housing laws against steering if she provided the information. Even so, she told Helling that after he had done his own research, he could talk with Gortler about his findings.

“Neil and you can discuss that,” she said, “Privately when, you know . . . But I want you to get a feel of the town, of the different towns, what makes those towns tick. . . . And I can’t really give you that stuff without telling you to just do some research.”

Finally, Leyden told Gortler that he could give Helling “whatever information he’s looking for, ’cause he’s a standup guy.”

Following their meetings, the agents sent Helling 31 house listings and Jimenez 27. Helling’s fell in areas that averaged 76 percent white; Jimenez’s averaged 69 percent white. For both men, the listings spread across similar areas of Great Neck, Port Washington and Manhasset.

The agents’ choices for the two customers differed in one place:

They gave only Helling listings in the Roslyn school district, a total of six. The community’s composition has remained largely stable from 2010 to 2017, when the census counted the population at 80 percent white, less than 1 percent black, 6 percent Hispanic and 13 percent Asian.

Comparable numbers of similarly priced homes – approximately 20 -were on the market in the area at the times of the two tests, according to Zillow, the internet-based house-listing service. Zillow drew the data for Newsday at no cost from the Multiple Listing Service of Long Island, the online network used by agents to keep up with properties for sale.

Newsday later compared how the tests had played out for Jimenez and Helling as they sat side by side. Both keyed on how Leyden had focused on community demographics only with Helling.

“The subtext was clear,” Helling said. “They were going to steer me in directions, again, that they thought that I would want, or that would be better for me. Probably white, you know, or something along those lines.

“And they knew – the way they were saying those things, they knew it was wrong. They knew what they were doing was wrong. But they would help me because that’s how they wanted to ingratiate themselves.”

Jimenez said: “I’m actually surprised that nothing like that was said to me, that I was not offered at least under the table like that that maybe I would be more comfortable in certain areas.”

Experts’ Findings

Freiberg: The agent made troubling statements to the white tester that the tester might be “more comfortable” in a school district with children that the tester’s children could “relate to,” which suggests steering. The agent did not make these types of remarks to the Hispanic tester. While many of the listings selected by the agent for both testers were in areas of similar racial composition, the agent did not provide any listings to the Hispanic tester in Roslyn, the school district with the greatest white student population of all the areas selected.

Schwemm: There is possible evidence of steering based on demographic comments made to the white tester and not to the Hispanic tester. There is lots of overlap in the listings (indicating no discrimination), but there is blatant differential treatment regarding the imbalance of listings in Roslyn (6 to white tester vs. 0 for Hispanic tester). This would be a possible violation, but follow-up tests of this agent needed to justify litigation.

Agent’s Response

Newsday sent Leyden and Gortler letters detailing the findings of the tests, invited them by letter and email to view video recordings of their interactions with testers and requested interviews. They did not respond. Leyden did not respond to a phone message from Newsday to her office requesting comment. Gortler said when contacted: “I have absolutely no comment. Thank you.” Their company, Laffey Real Estate, did not respond to requests for comment.

Sources: Demographic data in maps from Census Bureau 2016 American Community Survey five-year estimates.

Segregation

The segregation of blacks and whites has been embedded on Long Island as firmly as the Meadowbrook Parkway.

Heading north from the South Shore bayfront, the six-lane road divides overwhelmingly minority Freeport from overwhelmingly white Merrick; then overwhelmingly minority Roosevelt from overwhelmingly white North Merrick; then overwhelmingly minority Uniondale from East Meadow, where seven of 10 residents are white.

A swath of asphalt, concrete, grass and trees framed by green space, the parkway forms a barrier between communities that are as little as 1 percent white and as little as 2 percent black. The demarcations are stark even as the road serves as a conduit for more than 70,000 cars daily.

Long Island has 291 communities Most of its black residents live in just 11

As one of the most segregated suburbs in America, Long Island is crisscrossed by racial barriers. Some, like the Meadowbrook, are visible. Some are the invisible product of historical forces including zoning regulations, mortgage redlining, the boundaries of 124 school districts, housing prices, and racial steering and blockbusting — a tactic used by real estate agents to drive up sales, and commissions, by inducing blacks to move into a white neighborhood and then warning whites that property values were about to plummet.

For three years, Newsday investigated real estate practices on Long Island using a testing system in which whites and minorities, acting as home seekers, were paired to gauge how real estate agents treated them. The probe found that white testers were shown neighborhoods with higher proportions of white residents than black testers were, while the black testers were shown homes in more integrated neighborhoods. It also showed that certain minority areas were largely overlooked for everyone.

The divides are taken for granted even in places where they dictate that black and Hispanic children will learn only with black and Hispanic children, and white children will learn only with white children, in elementary schools a mile apart.

After studying Long Island, Myron Orfield, director of the Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity at the University of Minnesota Law School, sees “hard racial barriers where black communities are next to white communities and they stay very firm.” Orfield adds: “On Long Island, there’s hard walls. It’s a tough, tough wall there. When you see those hard, differential walls, underlying that there’s usually bigotry and prejudice that’s maintaining those hard walls.”

Half of Long Island’s black population lives in just 11 of the Island’s 291 communities, and 90 percent lives in just 62 of them, according to 2017 census estimates.

The concentrated housing pattern ranks the Island near the top nationally in statistical analyses of segregation.

Researchers use a standard called the dissimilarity index to measure racial and ethnic divisions. Put simply, the index identifies the percentage of two groups – for example, blacks and whites – that would have to move so that the members of each group become evenly distributed in a particular area.

The higher the index on a scale of zero to 100, the greater the segregation. At 100, blacks and whites would be totally separate. Any score above 60 indicates high segregation, researchers say.

Nassau County’s score of 78 ranked it as America’s most segregated county among those with 1.2 million-1.6 million residents, according to data from the 2010 census, the most recent performed.

The data also ranked Nassau the fourth most segregated county in New York State, behind the much larger and urban counties of Brooklyn and Queens, as well as Wyoming, an upstate county with a little more than 40,000 residents.

“This is typical of what we call hyper-segregated patterns,” says Douglas S. Massey, a Princeton University professor of sociology and public affairs who studies residential segregation.

With an index of 63, Suffolk County ranked 10th in the nation among similarly sized counties, and 19th on New York State’s roster of urban and suburban counties, according to the census data.

Combining the two counties to measure Long Island as a whole, Brown University sociology professor John Logan ranked the Island’s black-white segregation level 10th among 50 metropolitan areas with the largest black populations in the country. He calculated the index at 69.

The Island’s segregation stands at this level despite a decline in the index from 1990 to 2010, with Nassau falling 4 percentage points and Suffolk 7 points. It also accompanies climbing segregation in already highly segregated schools.

Rising Hispanic and Asian populations have driven up the proportions of minorities in Long Island’s schools while white representations have fallen, according to a Newsday analysis of state Education Department data.

White students composed 89 percent of public-school students in 1976. In 2018, they made up a little more than 50 percent. Hispanic students increased from 3 percent to 28 percent, while Asian students’ share rose from less than 1 percent to 9 percent from 1976 to 2018.

The black student percentage was relatively steady compared to other minority groups. Black students composed 7 percent in the 1976-77 school year, hit a high of 12 percent in 2000-01, then declined to 10 percent by 2018.

The demographic shifts were not balanced across all school districts. Only a handful have absorbed most of the black students, while white students remain in predominantly white districts.

The student bodies of 47 of Nassau’s 56 school districts were less than 10 percent black in 1976. The proportion of black students has risen above 10 percent in only nine of them. As a result, districts are more segregated than they were four decades ago.

In the last school year, 80 percent of white students attended schools where, on average, whites made up three-quarters of the students. In contrast, only 16 percent of black students attended majority white schools, down from 53 percent in 1976.

Lorna Lewis, superintendent of the Plainview-Old Bethpage School District, voiced concern over how neighborhood barriers, which affect school district boundaries, can adversely impact children’s educational opportunities.

During a drive along Clinton Road in Garden City into Clinton Street in neighboring Hempstead Village, Lewis reflected on the different educational opportunities and resources available in the school districts of those two communities.

She said it was a block “that divides the opportunity.”

“To me, that should not be,” added Lewis, whose term as president of the New York State Council of School Superintendents ended June 30.

“Our education should not be designed by the pocketbook, the ZIP code, the lines that we draw,” Lewis said. “That should not be the reason for educational outcomes. It really shouldn’t. And Long Island is full of that.”

Segregation was built into Long Island from its mid-20th century birth as an iconic American suburb.

A significant presence of African Americans on the Island began with slavery. According to a recent exhibit at the Long Island Museum, the 1698 census of Long Island’s population recorded 1,053 African Americans among a population of 8,261.

The Great Migration of blacks from the South to the North seeking greater opportunity brought an influx of black people to the Island in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, well before enactment of fair-housing laws in an era “when segregation was considered to be very legitimate,” Logan said.

Many left the Jim Crow South hoping to find a better life, only to find segregation in the North as well.

Perhaps most notoriously, William J. Levitt, visionary creator of affordable suburban tracts, marketed the prefabricated, concrete-slab homes that would become Levittown with restrictive covenants barring leasing and sales to blacks.

“The tenant agrees not to permit the premises to be used or occupied by any person other than members of the Caucasian race,” one such covenant read. “But the employment and maintenance of other than Caucasian domestic servants shall be permitted.”

In a 1954 interview with the “Saturday Evening Post,” Levitt explained his racial exclusion policy this way:

“If we sell one house to a Negro family, then 90 to 95 percent of our white customers will not buy into the community. That is their attitude, not ours. We did not create it and we cannot cure it. As a company, our position is simply this: we can solve a housing problem or we can try to solve a racial problem. But we cannot combine the two.”

Eugene Burnett, who turned 90 in March, recalls driving to Levittown in 1950 to look at its brand-new houses, as so many veterans did. He and an Army buddy were interested in moving their families to the suburbs. Burnett was newly married and had been discharged from the service the year before.

“I didn’t even know where Long Island was. It took us all day to find Levittown,” remembers Burnett, who lived in the South Bronx then.

The salesman balked, telling Burnett, “It’s not me, but the owner of this establishment has not at this time decided to sell to Negroes.”

“That was a real shock to me because while we were in the service, we used to tease the southern [black] soldiers about conditions in their states,” Burnett says, adding, “I didn’t expect they could tell me that, right out in the open in the state of New York, that they were going to discriminate against me.”

After the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated racial covenants in 1948, Levitt removed the clauses from company documents in 1949 but said he would continue to accept only white families. The discriminatory practice continued until April 1968, six days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., when the company announced it would adopt a policy of “open housing” as a memorial to King.

Listen to the Newsday and Levittown podcast: A paper’s crusade and a history of discriminationin LI’s foundational suburb

ERASE Racism, a Syosset-based social justice advocacy organization, noted in a report that “not one of Levittown’s 82,000 residents was African American” in 1960.

To this day, Levitt’s landmark Long Island settlement is home to few African Americans. In 2017, the census estimated the population at 75 percent white, 14 percent Hispanic, 7 percent Asian and 1 percent black.

The exclusion of blacks from Levittown and other suburban communities had financial consequences that reverberate today.

Richard Rothstein, author of “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America,” calculated the wealth-building opportunity denied blacks who were barred from Levittown.

Rothstein wrote that Levittown homes sold for around $8,000 in 1948, the equivalent of $75,000 in today’s dollars. In 2017, the median sales price of a Levittown house without major remodeling was $350,000 and up. The current median sales price in Levittown is $460,000, according to the Multiple Listing Service of Long Island.

“White working-class families who bought those homes in 1948 have gained, over three generations, more than $200,000 in wealth,” he wrote.

An acknowledgment: Newsday missed a critical chance to leadSegregation hardened rapidly on the Island starting around the time of the civil rights movement, propelled by white flight, racial steering and blockbusting by real estate agents in towns that today have the largest minority populations.

Elmont, Freeport, Hempstead, Lakeview, Westbury, Uniondale and Valley Stream in Nassau County, and Wheatley Heights in Suffolk County, all experienced panicked sell-offs by white residents who believed that property values would fall as blacks moved in.

The fastest white-to-black swing took place in Roosevelt, a town of 17,000 residents on the South Shore.

In 1960, Roosevelt was 82 percent white and 17 percent black. A decade later, the white share of the population had plummeted to 32 percent and the black share had swung up to 67 percent. The population in 2017 was estimated at 1.4 percent white.

Rita Lampkin and her husband, who are African American, were part of the demographic flip. In 1968, the couple looked to move from Queens to the suburbs with their two children. Lampkin, 88, knew Roosevelt, where she worked in the public library.

She recalls that a group promoting integration advised her to consider communities where the racial makeup appeared stable rather than communities such as Roosevelt, where the black population was surging.

The family bought a Cape-style house that backs up on a stand of trees and a streambed. Asked how she felt about the exodus of whites and the arrivals of blacks, she laughs. “Well my reaction was, let them leave. The blacks are just as good neighbors.”

In 1960, Lakeview’s population was about evenly split by race, 48 percent white and 52 percent black. That year, a racially mixed group of residents complained to the state attorney general that agents from 10 real estate brokerages had gone door to door with messages about the community’s changing demographics.

A decade later, Lakeview’s even black-white split was gone: The 1970 census counted 82 percent of residents as black and 17 percent as white. The transformation was long-lasting. The 2017 census estimate put the breakdown at 74 percent black, 18 percent Hispanic, 2 percent white and almost 1 percent Asian.

Elmont also saw a dramatic racial swing.

In 1964, a white couple, Don Olson and his wife, moved with their three children from the Bronx to Elmont, a Nassau community bordering Queens. Racial change swept the area in the 1970s.

“There was blockbusting in that time,” Olson said in an interview two years ago when he was 81. Olson died last August.

“There were commercials and notices in our mailboxes, and things like that,” he recalls. “Actually, the people that left, they left overnight. They sold their houses, but they did it quietly.”

Olson stayed. He spoke approvingly of the diversity of his neighbors.

“My next-door neighbor here is from Vietnam. And my neighbor behind me is from Vietnam also,” he says, adding, “My next-door neighbor is Spanish.”

Barred from Levittown, Army veteran Burnett and his wife, Bernice, bought a home where they still live in Suffolk’s Wheatley Heights, in 1960. By then, he was a sergeant on the county police force.

They were wary through their first nights there.

“In those days they would burn your house down the night before you moved in,” Burnett remembers. “I moved in here in the middle of the night and I stayed up all night sitting at the door because I had my babies in here.”

And, he says, he had his revolver – “my .38 special” – at the ready, just in case. But nothing violent unfolded.

Asked why he would risk moving into a community where some whites objected to his family because of their race, Burnett says:

“I’m going to live my life as a free man. And the opportunity was here for my children. I didn’t want my children to go to any kind of segregated school, even though the superintendent here told me I was crazy. But look what happened. Was I crazy? Look, I got three professional children out of it.”

He lists their occupations: a son is an architect, a daughter is a physician, and another daughter is a pharmacist.

In 1976, the Wheatley Heights Neighborhood Coalition filed the first Long Island-based federal court suit alleging steering by real estate companies and agents.

Wheatley Heights was 5 percent black at the time. It was bordered by predominantly black Wyandanch and predominantly white Deer Park and Dix Hills. The suit alleged that agents showed black people homes only in Wheatley Heights while never showing white buyers there. It also charged that agents never showed properties in nearby Dix Hills or Deer Park to blacks.

Two years later, a federal judge barred practices including racial steering and boycotting or retaliating against Wheatley Heights residents.

Still, demographic changes moved inexorably through Wheatley Heights, which today is served by a highly rated school district and boasts a 2017 median household income of $111,600, one of the highest in Suffolk County. The population breakdown: 49 percent black, 21 percent white, 10 percent Asian and 14 percent Hispanic.

Fifty years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling struck down legally sanctioned segregated schools, the ERASE Racism advocacy group concluded in 2004 that “racial isolation is the norm for Long Island’s residential neighborhoods and racially separate and unequal is the norm for Long Island’s public schools.”

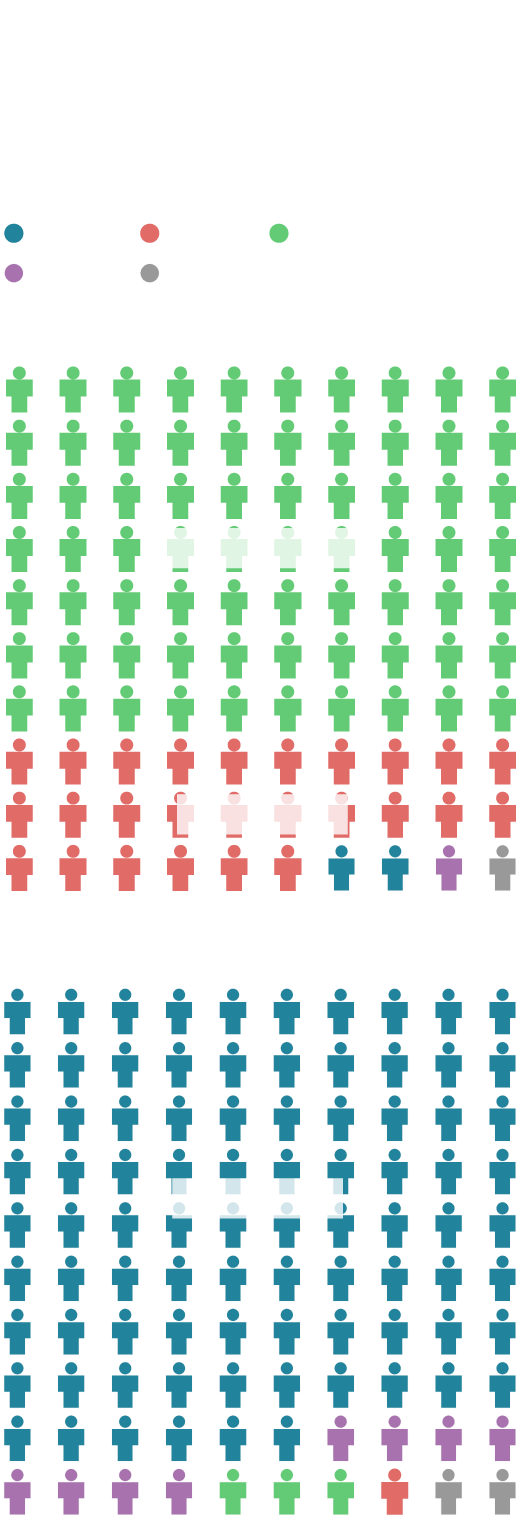

Where Hempstead abuts Garden City, the 461 black and Hispanic children of Jackson Main Elementary in Hempstead grew up for the year with just 12 white fellow students. One mile away, the 132 white children of Garden City’s Locust School encountered only five Hispanic and two black classmates.

Two schools one mile apart

Jackson Main Elementary has a dramatically smaller proportion of white students than neighboring Locust Elementary School.

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

Other

Jackson Main Elementary School

Locust Elementary School

70% Hispanic

86% White

26% Black

Two schools one mile apart

Jackson Main Elementary has a dramatically smaller proportion of white students than neighboring Locust Elementary School.

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

Other

Jackson Main Elementary School

70% Hispanic

26% Black

Locust Elementary School

86% White

Source: New York State Education Department, 2017-18

They live in a community that has grappled with a link between race and residence.

In 2017, after a more than decade-long legal battle waged by advocacy groups, a federal judge ruled that the Village of Garden City had “acted with discriminatory intent” by rezoning publicly owned land to prevent construction of affordable housing. Last year, the court ordered the village to pay $5.3 million in attorney fees and costs to the plaintiffs’ lawyers.

This year, Nassau County settled a separate housing discrimination case that alleged the county had steered affordable housing into minority communities. The county agreed to pay $5.4 million to promote mixed-income affordable housing.

Since then, the county has agreed to negotiate preliminary tax breaks for a proposed development of 150 apartments in Garden City on Stewart Avenue, across from the Roosevelt Field mall, 15 of which are to be affordable units.

– With Ann Choi

Schools

Long Island real estate agents sell schools as much as houses.

School district ratings are among the most zealously watched indicators of quality of life by Long Island homeowners, not least because they can influence home values.

In many of Newsday’s 86 paired tests, agents applied a laser-like focus on districts, highlighting their perceived quality when recommending places that house hunters should consider buying – or avoid.

As one real estate agent explained it: “So, more important than Syosset is schools, because everything is by schools on Long Island.”

That reliance on school ratings as a top selling point can empower Long Island real estate agents to serve as gatekeepers for 124 highly delineated districts whose test scores, graduations rates and ethnic and racial compositions vary sharply. In playing the gatekeeper role, they risk running afoul of fair housing standards because discussing school quality can become a proxy for talking about a community’s makeup.

As the National Association of Realtors stated in a 2014 post on its website, “Discussions about schools can raise questions about steering if there is a correlation between the quality of the schools and neighborhood racial composition.”

Characterizations about schools with low test scores, for example, or comments that reference a “‘community with declining schools’ become code words for racial or other differences in the community,” the post states. As a result, such comments become “fair-housing issues.”

Additionally, fair-housing experts say touting or disparaging schools can put agents in legal jeopardy because many lack the expertise to make such judgments.

“Since when did real estate agents become experts on schools?” asked Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, who served as a Newsday consultant.

“It’s ridiculous because they cannot, they should not be trusted to provide objective information about schools and school performance rates,” Freiberg said.

“I might go into an area and maybe it’s not the highest scores I’m looking for for my son. Maybe it’s the music program. There could be a lot of different reasons why I would think a school was better or worse for my son that has nothing to do with test scores, certainly nothing to do with race.”

While some agents tested by Newsday told customers that they were legally barred from talking about schools, fair-housing experts say agents may provide information so long as it is strictly factual – and provided equally to customers.

The National Association of Realtors made clear that agents have a narrow pathway that involves sticking to “objective information,” not their personal opinions.

The author suggested that agents provide prospective homebuyers with school or community websites that provide ratings and data.

“The best thing a Realtor can do is guide them to third-party information, so they can make a decision on their own,” the post recommends.

Some agents touted districts as highly rated. Some denigrated districts as undesirable places to invest in homes. Whether based on facts or simply their own beliefs, some expressed perceptions about district performances that were in line with pointing buyers toward communities with substantial white populations and away from more integrated areas.

Some agents advised testers to research schools on their own through websites that provide educational performance data. One agent went further by telling house hunters to review published data to also determine community socioeconomic conditions.

“I’m not allowed to tell you where to go, where not to go. But I could tell you where to look, you know. And then you look,” RE/MAX agent Joy Tuxson told white tester Brittany Silver.

“Everything is online for the school districts. You’re going to see who graduates. How many kids. The ethnic breakdown, how many free lunches. You can get a good idea of the socioeconomic makeup of the neighborhood when you look at the school districts.”

Joy Tuxson

RE/MAX

East Meadow

Tuxson also made a disparaging comment about Wyandanch to the white tester.

When speaking with Silver’s paired tester, Payal Mehta, who is South Asian, Tuxson related advice she had given a family member who was house hunting.

“I sold my nephew a house, him and his bride … I said, ‘… you sent me houses with seven different school districts,'” Tuxson recalled, adding that she asked him, “‘Do you really want your future children going to Amityville school districts?'”

Asked for help finding $500,000 homes within 30 minutes of Bethpage, Tuxson provided comparable listings to both testers.

Tuxson did not respond to a letter, an email or a phone call from Newsday requesting comment.

Newsday fair housing consultant Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, said that “both testers received listings in similar areas, but one or more statements made by the agent were discriminatory or involved possible steering away from predominantly minority communities and school districts.”

Noting that “the agent shared derogatory opinions about crime in the minority community of Wyandanch only with the white tester,” consultant Robert Schwemm, professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law, wrote, “Whether she was wrongly stereotyping or not, she provided greater information to the white tester than to the Asian.”

Schwemm added: “The agent’s comments about Wyandanch and Amityville schools suggest that these towns could sue for the agent’s steering whites and Asians away from them – but it would be advisable to do additional testing by black and/or Hispanic testers to see if this agent makes similar comments to these minorities.”

Kerry McGovern, vice president of communications for RE/MAX LLC, said in a statement: “We have spoken with the franchise owners whose agents were included in the inquiry and are confident they have taken this matter seriously and are committed to following the law and promoting levels of honesty, inclusivity and professionalism in real estate.”

In the Amityville school district, more than 90 percent of the students are black or Hispanic.

The district had a 77 percent four-year high school graduation rate in 2018, including 20 percent who earned advanced designation diplomas after passing at least eight Regents exams, according to New York State Education Department data.

Most of neighboring Massapequa is part of a 93 percent white school district, where 97 percent of the students graduate in four years, 66 percent with advanced designation diplomas. But some of East Massapequa is zoned for the Amityville school district.

The boundary was key to some agents.

You don’t want [District] 6 in Massapequa, because that takes in Amityville, and you’re not going to like those schools.

Margaret Petrelli

Realty Connect USA agent

Levittown

Describing Massapequa as “beautiful,” Realty Connect USA agent Margaret Petrelli provided a white tester with a list of seven districts whose high school’s student populations averaged nearly 85 percent white. The agent did not provide the black tester with a list of school districts to consider.

“If you’re in Massapequa, you only want School District 23,” she counseled the white tester, using a Multiple Listings Service reference number, before continuing:

“You don’t want [District] 6 in Massapequa, because that takes in Amityville, and you’re not going to like those schools.”

Newsday’s consultants, Freiberg and Schwemm, concluded separately, based on information Newsday provided them, that Petrelli’s statements and actions raised evidence of racial steering and discriminatory treatment. (Petrelli also had asked the black tester for identification, but not the white tester).

Petrelli initially made an appointment to view the video of her interactions with testers at Newsday, but due to a scheduling conflict Newsday asked her to choose a different time. She answered that an alternate time would not work for her. She has since not responded to a follow-up email or phone call.

Five agents drew sharp school district boundary distinctions about choosing homes that carried addresses in the central Nassau community of Westbury.

Some of those homes are in the Westbury school district, whose student body is just under three quarters Hispanic and one quarter black. The high school graduation rate last year was 79 percent, with 23 percent earning Regent’s diplomas with advanced designation, according to the state Education Department.

Other homes are in the East Meadow school district, whose makeup is 54 percent white, 21 percent Hispanic, 20 percent Asian and 4 percent black. The high school’s graduation rate was 93 percent, with 63 percent of the graduates earning Regents diplomas with advanced designation.

Salisbury is a hamlet of just under 2 square miles that carries a Westbury address but falls in the East Meadow school district. It is bounded on the north by Old Country Road, on the west by Eisenhower Park, on the south by Salisbury Park Drive and to the east by the Wantagh State Parkway.

The majority of Salisbury’s 12,000-plus population is white, at 70 percent. Asians compose 15 percent of the population, Hispanics nearly 14 percent and blacks not quite 1 percent.

Longtime residents recall intense resistance to integration.

Diane Kremin lived in Salisbury for 42 years before selling her home in January. In her early years in the community, she remembers people saying, “I won’t be the first to sell to a black but I’ll be the second,” along with stories about people threatening, “If you sell to people we don’t like we’ll burn your house down.”

Local groups pushed for a separate ZIP code for Salisbury over the jurisdictional confusion with Westbury in the ’70s and again around 1990, said Helen Meittinis, a local civic association president.

Kremin, who is white, said she participated to distinguish the area from Westbury – where today more than six of 10 residents are minority – and to protect property values.

“Westbury schools didn’t have a good reputation because they were more black than white. It’s primarily the school system. You didn’t want to be known as Westbury,” recalls Kremin, who sold her house to a Middle Eastern couple and adds, “It’s very different today because the value doesn’t decline because of diversity anymore.”

The five agents who mentioned Westbury to customers made clear that they meant Salisbury because of its location in the East Meadow school district. Only one of the agents suggested houses – a total of three – in the Westbury school district. In comparison, the agents offered 19 houses in Salisbury.

Realty Connect USA agent Petrelli, for example, told a white tester: “You have Salisbury and Westbury. You have – which, of course, I will tell you, there’s one school district that you’ll stay away from.”

Watch videos of the testsIn the opinions of two agents tested by Newsday, the predominantly minority community of Elmont was an area to avoid “school district-wise” or based on “statistics.”

In the judgments of state and federal education agencies and a noted school advocacy organization, Elmont Memorial High School — one of five high schools from demographically disparate communities that together make up the Sewanhaka Central High School District – has been worthy of accolades.

The statements by the two agents, whose conduct produced evidence of steering in the view of Newsday fair-housing consultants, offer a window into how agents can guide house hunters based on negative assumptions that run parallel to race.

A largely black and Hispanic community, Elmont hugs the Nassau County border with Queens. In 2018, the student body of its high school, Elmont Memorial, was roughly 90 percent black and Hispanic. The four-year graduation rate was 96 percent, with 47 percent of the students earning advanced Regents Diplomas, down from 53 percent the year before.

The school boasted a four-year graduation rate for economically disadvantaged students that was higher than the average across all Nassau County schools: 95 percent earning diplomas, with 40 percent earning advanced Regents Diplomas, compared with the corresponding county figures of 80 percent and 35 percent.

Elmont Memorial has been recognized as a school of excellence by the U.S. Department of Education; received a New York State Excelsior Award; was named a New York State Blue Ribbon School of Excellence; and received the “Dispelling the Myth” award from the Education Trust.

“I would challenge anyone to come in and see how well our students do in Elmont and how, in terms of their graduation rate, the colleges and universities they get accepted into, the national recognition that they have received in such areas as the arts, Model UN and science research,” said Ralph Ferrie, in an interview before he retired as superintendent of the Sewanhaka Central High School District last June.

“It’s disappointing that people would look at a community and, just based upon its demographics, come to the conclusion … that that is not a quality high school.”

A researcher who analyzed Nassau County schools over five years, culminating in a 2014 report, said race factored into where white parents send — or don’t send — their children to school.

Amy Stuart Wells, a professor of sociology and education at Teachers College, Columbia University, was lead author of the 2014 report, “Divided We Fall: The Story of Separate and Unequal,” an investigation of Nassau County’s 56 school districts.

One facet of the research analyzed the relationship between home property values and neighborhood and school district demographics.

“And what you find at that time, around 2014, was that the percentage of black students in a school district decreased property value of the same quality house with the same lot size and everything else by $50,000 ,” Wells said. “So you start to understand the process by which segregation happens again and again.”

Wells studied what was happening to homes priced at the 2010 median in Nassau County of $415,000 as the percentage of black and Hispanic population rose from 30 to 70 percent.

The way the study put it: “both models indicate that a one-percent increase in black/Hispanic enrollments is associated with a 0.3 percent decrease in home values. Put another way, almost $50,000 in price would separate two otherwise similar homes, one located in a district that is 30 percent black/Hispanic, and other located in a district with 70 percent black/Hispanic enrollments (given Nassau County’s 2010 median home price of $415,000).”

She continued that people’s perceptions of an area really matter, and often that perception is “racialized.” The study showed that a white buyer is more likely “to choose the predominantly white and/or Asian school district, without ever stepping foot in the other school district.”

After interviewing real estate agents, Wells said her research team found that some held views on school districts that were not necessarily based on performance but often were influenced by the racial makeup of the students.

She said the research team looked at two school districts that had similar housing stocks and similar socioeconomic populations – but differed racially. “The real estate agents would talk about the quality of those districts,” Wells said, adding:

“And when we actually went in and looked inside the schools, there didn’t seem to be a huge difference at all in the curriculum and the quality of the teachers. So, they [real estate agents] do play an important role in steering people away from certain districts that are becoming more racially, ethnically diverse and less white, in particular.”

– With Rachelle Blidner

Correction: The section of Massapequa that falls into Amityville schools was incorrect in a previous version of this story.

Rockville Centre

In Rockville Centre, a south shore village in Nassau County, the sports fields bustle with youth soccer and lacrosse teams and the restaurants and bars downtown attract lively crowds.

The bells ring for mass from the imposing three-level tower at the Cathedral of St. Agnes, seat of the Diocese of Rockville Centre, which ministers to Catholics in Long Island’s two counties.

It’s a place where generations of families settle, attend well-regarded schools and have a quick train ride into the city.

While attending the highly rated schools is a benefit open to all, where you live in Rockville Centre makes a difference.

For some, a Tudor-style home on a wide, leafy street is an option. The median price for a home in Rockville Centre was $615,000 in 2017, according to the 2013-17 American Community Survey done by the U.S. Census Bureau. The Multiple Listing Service of Long Island put the median price at $612,500 in June 2019.

Otherwise, you may live on the West Side.

That’s where the majority of black families reside in Rockville Centre, in public housing created by a 1960s urban renewal project that uprooted the black community there and was among the most contentious of such projects on Long Island.

Hispanic residents are concentrated in apartments, live over stores or in smaller homes.

Heading still west across Peninsula Boulevard is another section with a Rockville Centre ZIP code made up mostly of black people, although children there attend schools in the predominantly minority Malverne district.

Rockville Centre does not have the whitest complexion on Long Island – 75 percent of its residents are white, compared with 90 percent in Garden City and 86 percent in nearby Oceanside, for example, according to U.S. Census figures.

A Newsday investigation of home-selling practices on Long Island, however, found this community to be one in which white home buyers were significantly more likely to be offered a listing than were minorities.

Tonya Thomas, her husband and two daughters are a black family that has lived in a highly desirable area of Rockville Centre since 2004. They landed in the village after they looked for homes on the North Shore and Garden City but couldn’t find a suitable place within their budget.

They also experienced resistance in some of those communities, Thomas said, including people not answering the door for scheduled showing appointments or arriving to an address to find that the home supposedly had been sold just minutes before.

When told of Newsday’s findings involving Rockville Centre, she said it was not surprising given Long Island’s history with segregated neighborhoods.

“Although my husband and I did not have a negative house-buying experience in Rockville Centre, I cannot say that that was the case for many communities that we visited on Long Island,” she said. “It took us two years to find a house.”

She said Rockville Centre is a wonderful community with lots of amenities where her family has been “blessed” to have great neighbors and an excellent school district where her children have thrived.

“It can be challenging finding a community that provides all the resources and experiences that one wants for their family,” Thomas said. “We all, no matter who we are or where we come from, want the same things.”

The black-white racial history of Rockville Centre began early in the 20th century in a neighborhood on the village’s West Side.

Black families, many of them Southern migrants working as domestics or laborers, found modest housing in an explicitly segregated area north of Sunrise Highway up to Lakeview Avenue, and east of Peninsula to North Centre Avenue. Ernestine Small, now 82 and living in senior housing in Uniondale, recalled growing up in the West Side neighborhood in the 1940s and ’50s, the daughter of a bank caretaker and a domestic who came north in search of a better life. Not all the housing was run down, she said, and the neighborhood was active and cohesive.

“Our life was good,” she recalled in an interview. “I came out of a working family. My father had a beautiful garden, and all he raised my mother canned and cooked, so we had plenty.”