The segregation of blacks and whites has been embedded on Long Island as firmly as the Meadowbrook Parkway.

Heading north from the South Shore bayfront, the six-lane road divides overwhelmingly minority Freeport from overwhelmingly white Merrick; then overwhelmingly minority Roosevelt from overwhelmingly white North Merrick; then overwhelmingly minority Uniondale from East Meadow, where seven of 10 residents are white.

A swath of asphalt, concrete, grass and trees framed by green space, the parkway forms a barrier between communities that are as little as 1 percent white and as little as 2 percent black. The demarcations are stark even as the road serves as a conduit for more than 70,000 cars daily.

Long Island has 291 communities Most of its black residents live in just 11

As one of the most segregated suburbs in America, Long Island is crisscrossed by racial barriers. Some, like the Meadowbrook, are visible. Some are the invisible product of historical forces including zoning regulations, mortgage redlining, the boundaries of 124 school districts, housing prices, and racial steering and blockbusting — a tactic used by real estate agents to drive up sales, and commissions, by inducing blacks to move into a white neighborhood and then warning whites that property values were about to plummet.

For three years, Newsday investigated real estate practices on Long Island using a testing system in which whites and minorities, acting as home seekers, were paired to gauge how real estate agents treated them. The probe found that white testers were shown neighborhoods with higher proportions of white residents than black testers were, while the black testers were shown homes in more integrated neighborhoods. It also showed that certain minority areas were largely overlooked for everyone.

The divides are taken for granted even in places where they dictate that black and Hispanic children will learn only with black and Hispanic children, and white children will learn only with white children, in elementary schools a mile apart.

After studying Long Island, Myron Orfield, director of the Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity at the University of Minnesota Law School, sees “hard racial barriers where black communities are next to white communities and they stay very firm.” Orfield adds: “On Long Island, there’s hard walls. It’s a tough, tough wall there. When you see those hard, differential walls, underlying that there’s usually bigotry and prejudice that’s maintaining those hard walls.”

Half of Long Island’s black population lives in just 11 of the Island’s 291 communities, and 90 percent lives in just 62 of them, according to 2017 census estimates.

The concentrated housing pattern ranks the Island near the top nationally in statistical analyses of segregation.

Researchers use a standard called the dissimilarity index to measure racial and ethnic divisions. Put simply, the index identifies the percentage of two groups – for example, blacks and whites – that would have to move so that the members of each group become evenly distributed in a particular area.

The higher the index on a scale of zero to 100, the greater the segregation. At 100, blacks and whites would be totally separate. Any score above 60 indicates high segregation, researchers say.

Nassau County’s score of 78 ranked it as America’s most segregated county among those with 1.2 million-1.6 million residents, according to data from the 2010 census, the most recent performed.

The data also ranked Nassau the fourth most segregated county in New York State, behind the much larger and urban counties of Brooklyn and Queens, as well as Wyoming, an upstate county with a little more than 40,000 residents.

“This is typical of what we call hyper-segregated patterns,” says Douglas S. Massey, a Princeton University professor of sociology and public affairs who studies residential segregation.

With an index of 63, Suffolk County ranked 10th in the nation among similarly sized counties, and 19th on New York State’s roster of urban and suburban counties, according to the census data.

Combining the two counties to measure Long Island as a whole, Brown University sociology professor John Logan ranked the Island’s black-white segregation level 10th among 50 metropolitan areas with the largest black populations in the country. He calculated the index at 69.

The Island’s segregation stands at this level despite a decline in the index from 1990 to 2010, with Nassau falling 4 percentage points and Suffolk 7 points. It also accompanies climbing segregation in already highly segregated schools.

Rising Hispanic and Asian populations have driven up the proportions of minorities in Long Island’s schools while white representations have fallen, according to a Newsday analysis of state Education Department data.

White students composed 89 percent of public-school students in 1976. In 2018, they made up a little more than 50 percent. Hispanic students increased from 3 percent to 28 percent, while Asian students’ share rose from less than 1 percent to 9 percent from 1976 to 2018.

The black student percentage was relatively steady compared to other minority groups. Black students composed 7 percent in the 1976-77 school year, hit a high of 12 percent in 2000-01, then declined to 10 percent by 2018.

The demographic shifts were not balanced across all school districts. Only a handful have absorbed most of the black students, while white students remain in predominantly white districts.

The student bodies of 47 of Nassau’s 56 school districts were less than 10 percent black in 1976. The proportion of black students has risen above 10 percent in only nine of them. As a result, districts are more segregated than they were four decades ago.

In the last school year, 80 percent of white students attended schools where, on average, whites made up three-quarters of the students. In contrast, only 16 percent of black students attended majority white schools, down from 53 percent in 1976.

Lorna Lewis, superintendent of the Plainview-Old Bethpage School District, voiced concern over how neighborhood barriers, which affect school district boundaries, can adversely impact children’s educational opportunities.

During a drive along Clinton Road in Garden City into Clinton Street in neighboring Hempstead Village, Lewis reflected on the different educational opportunities and resources available in the school districts of those two communities.

She said it was a block “that divides the opportunity.”

“To me, that should not be,” added Lewis, whose term as president of the New York State Council of School Superintendents ended June 30.

“Our education should not be designed by the pocketbook, the ZIP code, the lines that we draw,” Lewis said. “That should not be the reason for educational outcomes. It really shouldn’t. And Long Island is full of that.”

Segregation was built into Long Island from its mid-20th century birth as an iconic American suburb.

A significant presence of African Americans on the Island began with slavery. According to a recent exhibit at the Long Island Museum, the 1698 census of Long Island’s population recorded 1,053 African Americans among a population of 8,261.

The Great Migration of blacks from the South to the North seeking greater opportunity brought an influx of black people to the Island in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, well before enactment of fair-housing laws in an era “when segregation was considered to be very legitimate,” Logan said.

Many left the Jim Crow South hoping to find a better life, only to find segregation in the North as well.

Perhaps most notoriously, William J. Levitt, visionary creator of affordable suburban tracts, marketed the prefabricated, concrete-slab homes that would become Levittown with restrictive covenants barring leasing and sales to blacks.

“The tenant agrees not to permit the premises to be used or occupied by any person other than members of the Caucasian race,” one such covenant read. “But the employment and maintenance of other than Caucasian domestic servants shall be permitted.”

In a 1954 interview with the “Saturday Evening Post,” Levitt explained his racial exclusion policy this way:

“If we sell one house to a Negro family, then 90 to 95 percent of our white customers will not buy into the community. That is their attitude, not ours. We did not create it and we cannot cure it. As a company, our position is simply this: we can solve a housing problem or we can try to solve a racial problem. But we cannot combine the two.”

Eugene Burnett, who turned 90 in March, recalls driving to Levittown in 1950 to look at its brand-new houses, as so many veterans did. He and an Army buddy were interested in moving their families to the suburbs. Burnett was newly married and had been discharged from the service the year before.

“I didn’t even know where Long Island was. It took us all day to find Levittown,” remembers Burnett, who lived in the South Bronx then.

The salesman balked, telling Burnett, “It’s not me, but the owner of this establishment has not at this time decided to sell to Negroes.”

“That was a real shock to me because while we were in the service, we used to tease the southern [black] soldiers about conditions in their states,” Burnett says, adding, “I didn’t expect they could tell me that, right out in the open in the state of New York, that they were going to discriminate against me.”

After the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated racial covenants in 1948, Levitt removed the clauses from company documents in 1949 but said he would continue to accept only white families. The discriminatory practice continued until April 1968, six days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., when the company announced it would adopt a policy of “open housing” as a memorial to King.

Listen to the Newsday and Levittown podcast: A paper’s crusade and a history of discriminationin LI’s foundational suburb

ERASE Racism, a Syosset-based social justice advocacy organization, noted in a report that “not one of Levittown’s 82,000 residents was African American” in 1960.

To this day, Levitt’s landmark Long Island settlement is home to few African Americans. In 2017, the census estimated the population at 75 percent white, 14 percent Hispanic, 7 percent Asian and 1 percent black.

The exclusion of blacks from Levittown and other suburban communities had financial consequences that reverberate today.

Richard Rothstein, author of “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America,” calculated the wealth-building opportunity denied blacks who were barred from Levittown.

Rothstein wrote that Levittown homes sold for around $8,000 in 1948, the equivalent of $75,000 in today’s dollars. In 2017, the median sales price of a Levittown house without major remodeling was $350,000 and up. The current median sales price in Levittown is $460,000, according to the Multiple Listing Service of Long Island.

“White working-class families who bought those homes in 1948 have gained, over three generations, more than $200,000 in wealth,” he wrote.

An acknowledgment: Newsday missed a critical chance to leadSegregation hardened rapidly on the Island starting around the time of the civil rights movement, propelled by white flight, racial steering and blockbusting by real estate agents in towns that today have the largest minority populations.

Elmont, Freeport, Hempstead, Lakeview, Westbury, Uniondale and Valley Stream in Nassau County, and Wheatley Heights in Suffolk County, all experienced panicked sell-offs by white residents who believed that property values would fall as blacks moved in.

The fastest white-to-black swing took place in Roosevelt, a town of 17,000 residents on the South Shore.

In 1960, Roosevelt was 82 percent white and 17 percent black. A decade later, the white share of the population had plummeted to 32 percent and the black share had swung up to 67 percent. The population in 2017 was estimated at 1.4 percent white.

Rita Lampkin and her husband, who are African American, were part of the demographic flip. In 1968, the couple looked to move from Queens to the suburbs with their two children. Lampkin, 88, knew Roosevelt, where she worked in the public library.

She recalls that a group promoting integration advised her to consider communities where the racial makeup appeared stable rather than communities such as Roosevelt, where the black population was surging.

The family bought a Cape-style house that backs up on a stand of trees and a streambed. Asked how she felt about the exodus of whites and the arrivals of blacks, she laughs. “Well my reaction was, let them leave. The blacks are just as good neighbors.”

In 1960, Lakeview’s population was about evenly split by race, 48 percent white and 52 percent black. That year, a racially mixed group of residents complained to the state attorney general that agents from 10 real estate brokerages had gone door to door with messages about the community’s changing demographics.

A decade later, Lakeview’s even black-white split was gone: The 1970 census counted 82 percent of residents as black and 17 percent as white. The transformation was long-lasting. The 2017 census estimate put the breakdown at 74 percent black, 18 percent Hispanic, 2 percent white and almost 1 percent Asian.

Elmont also saw a dramatic racial swing.

In 1964, a white couple, Don Olson and his wife, moved with their three children from the Bronx to Elmont, a Nassau community bordering Queens. Racial change swept the area in the 1970s.

“There was blockbusting in that time,” Olson said in an interview two years ago when he was 81. Olson died last August.

“There were commercials and notices in our mailboxes, and things like that,” he recalls. “Actually, the people that left, they left overnight. They sold their houses, but they did it quietly.”

Olson stayed. He spoke approvingly of the diversity of his neighbors.

“My next-door neighbor here is from Vietnam. And my neighbor behind me is from Vietnam also,” he says, adding, “My next-door neighbor is Spanish.”

Barred from Levittown, Army veteran Burnett and his wife, Bernice, bought a home where they still live in Suffolk’s Wheatley Heights, in 1960. By then, he was a sergeant on the county police force.

They were wary through their first nights there.

“In those days they would burn your house down the night before you moved in,” Burnett remembers. “I moved in here in the middle of the night and I stayed up all night sitting at the door because I had my babies in here.”

And, he says, he had his revolver – “my .38 special” – at the ready, just in case. But nothing violent unfolded.

Asked why he would risk moving into a community where some whites objected to his family because of their race, Burnett says:

“I’m going to live my life as a free man. And the opportunity was here for my children. I didn’t want my children to go to any kind of segregated school, even though the superintendent here told me I was crazy. But look what happened. Was I crazy? Look, I got three professional children out of it.”

He lists their occupations: a son is an architect, a daughter is a physician, and another daughter is a pharmacist.

In 1976, the Wheatley Heights Neighborhood Coalition filed the first Long Island-based federal court suit alleging steering by real estate companies and agents.

Wheatley Heights was 5 percent black at the time. It was bordered by predominantly black Wyandanch and predominantly white Deer Park and Dix Hills. The suit alleged that agents showed black people homes only in Wheatley Heights while never showing white buyers there. It also charged that agents never showed properties in nearby Dix Hills or Deer Park to blacks.

Two years later, a federal judge barred practices including racial steering and boycotting or retaliating against Wheatley Heights residents.

Still, demographic changes moved inexorably through Wheatley Heights, which today is served by a highly rated school district and boasts a 2017 median household income of $111,600, one of the highest in Suffolk County. The population breakdown: 49 percent black, 21 percent white, 10 percent Asian and 14 percent Hispanic.

Fifty years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling struck down legally sanctioned segregated schools, the ERASE Racism advocacy group concluded in 2004 that “racial isolation is the norm for Long Island’s residential neighborhoods and racially separate and unequal is the norm for Long Island’s public schools.”

Where Hempstead abuts Garden City, the 461 black and Hispanic children of Jackson Main Elementary in Hempstead grew up for the year with just 12 white fellow students. One mile away, the 132 white children of Garden City’s Locust School encountered only five Hispanic and two black classmates.

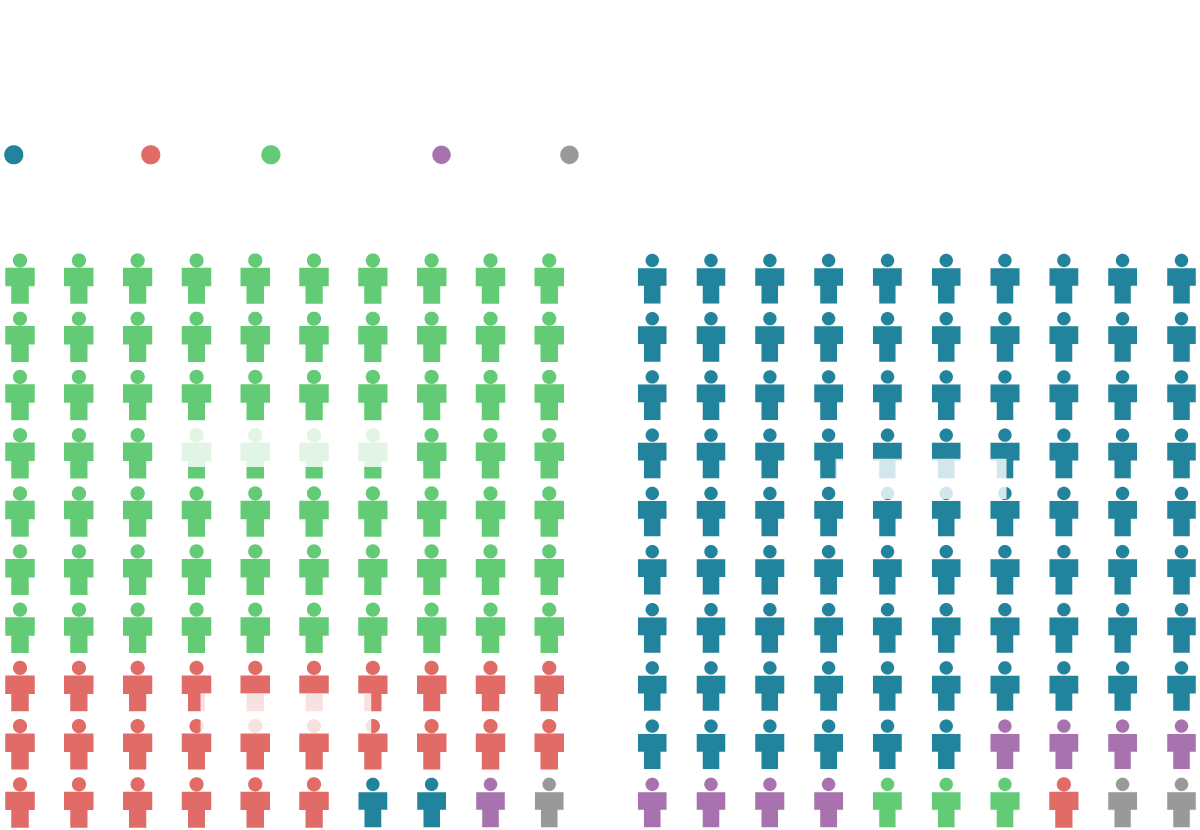

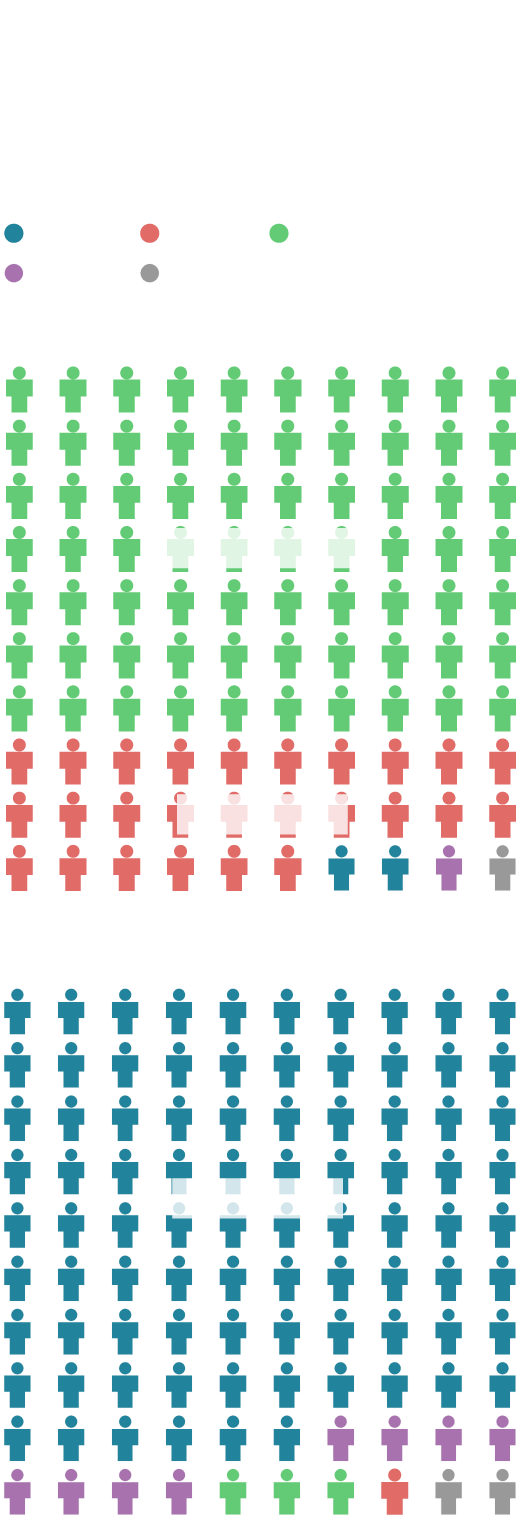

Two schools one mile apart

Jackson Main Elementary has a dramatically smaller proportion of white students than neighboring Locust Elementary School.

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

Other

Jackson Main Elementary School

Locust Elementary School

70% Hispanic

86% White

26% Black

Two schools one mile apart

Jackson Main Elementary has a dramatically smaller proportion of white students than neighboring Locust Elementary School.

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

Other

Jackson Main Elementary School

70% Hispanic

26% Black

Locust Elementary School

86% White

Source: New York State Education Department, 2017-18

They live in a community that has grappled with a link between race and residence.

In 2017, after a more than decade-long legal battle waged by advocacy groups, a federal judge ruled that the Village of Garden City had “acted with discriminatory intent” by rezoning publicly owned land to prevent construction of affordable housing. Last year, the court ordered the village to pay $5.3 million in attorney fees and costs to the plaintiffs’ lawyers.

This year, Nassau County settled a separate housing discrimination case that alleged the county had steered affordable housing into minority communities. The county agreed to pay $5.4 million to promote mixed-income affordable housing.

Since then, the county has agreed to negotiate preliminary tax breaks for a proposed development of 150 apartments in Garden City on Stewart Avenue, across from the Roosevelt Field mall, 15 of which are to be affordable units.

– With Ann Choi