Newsday has removed its paywall to allow everyone access to this groundbreaking and essential investigative project.

In one of the most concentrated investigations of discrimination by real estate agents in the half century since enactment of America’s landmark fair housing law, Newsday found evidence of widespread separate and unequal treatment of minority potential homebuyers and minority communities on Long Island.

The three-year probe strongly indicates that house hunting in one of the nation’s most segregated suburbs poses substantial risks of discrimination, with black buyers chancing disadvantages almost half the time they enlist brokers.

Additionally, the investigation reveals that Long Island’s dominant residential brokering firms help solidify racial separations. They frequently directed white customers toward areas with the highest white representations and minority buyers to more integrated neighborhoods.

They also avoided business in communities with overwhelmingly minority populations.

From the editor

Read more

Read less

What happens when white and minority prospective homebuyers seek real estate agents to help them find houses on Long Island?

More than 50 years after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the federal Fair Housing Act to prohibit discrimination in housing, this remains a core question for one of America’s oldest, most populous and most segregated suburbs.

The answer should be equal treatment for all by real estate agents and equal access for all communities.

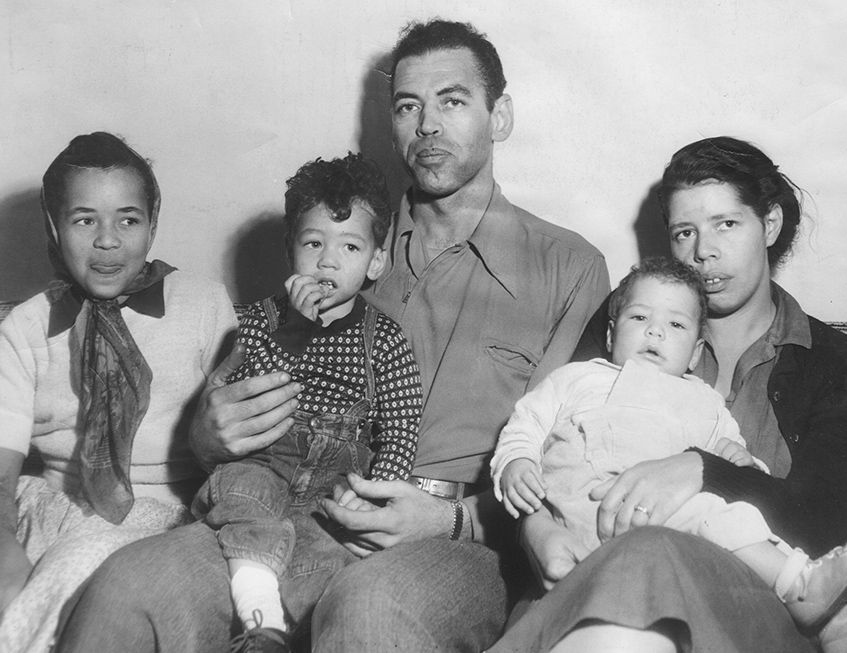

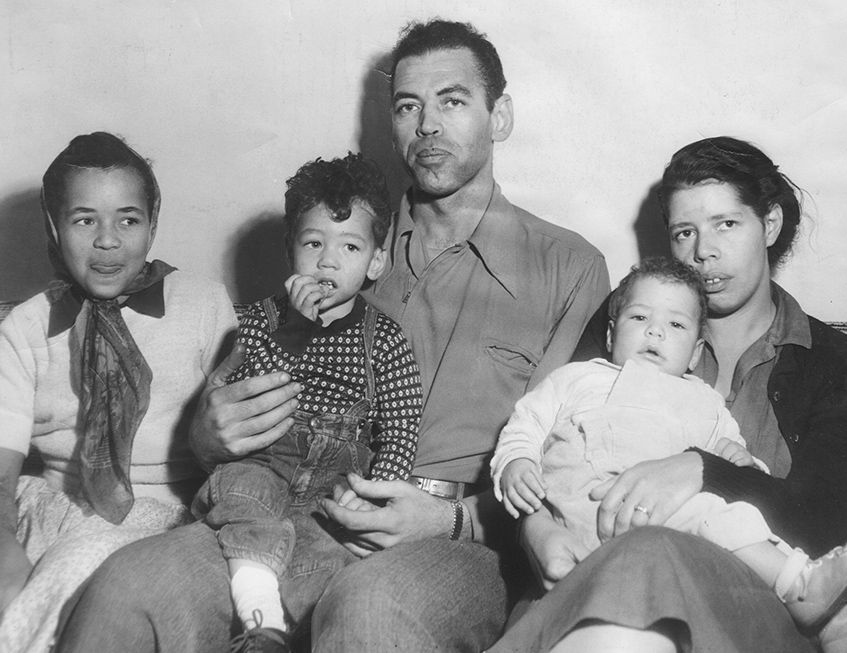

In the decades after World War II, Long Island experienced explosive growth as its communities swelled with returning veterans investing in homes and establishing roots. But opportunities were not the same for everyone in what was also an era of racially exclusive covenants and blockbusting tactics that separated communities along color lines.

Today, even though ours is an increasingly diverse region, the lines of separation stubbornly persist. We remain a Long Island Divided.

Real estate agents are central to homebuying and so important is their role that their training is specified by New York state. They are licensed by the state and their industry is regulated by federal and state agencies. They are expected to uphold federal, state and local laws requiring equal treatment for all and equal access to all communities. Federal law specifically protects homebuyers from discrimination based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status and disability.

Enforcement agencies rely on undercover tests — which reveal sometimes hidden inequalities in treatment — to investigate whether real estate agents deny equal opportunities in home buying. Posing as buyers, white and minority testers make identical requests to agents for help finding houses. The results are then scrutinized for evidence of fair housing violations such as “steering” testers to communities.

Newsday found that authorities had not conducted significant government fair housing testing among Long Island’s 27,000 licensed real estate agents for almost a decade.

So we undertook the task in a three-year investigation that is one of the most extensive ever conducted by Newsday.

Newsday engaged the Fair Housing Justice Center in Long Island City, an organization with the nation’s most extensive paired-testing experience, to help structure and implement testing and train testers. We engaged two nationally recognized experts in fair housing standards to analyze the results of our testing and then undertook a rigorous and thorough review of the findings.

We then notified all agents and agencies that were tested. If both experts found evidence of unequal treatment, Newsday contacted the real estate agencies and agents involved to make available a review of video we recorded of interactions among testers and agent and maps of listings offered. We invited them to meet with our reporting team to ask questions and to seek their reactions and responses. The Newsday team then reviewed the cases based on responses from agencies, agents and their representatives.

Our digital presentation provides readers access to our testing videos of interactions in cases where experts saw evidence of fair housing violations, mapping of listings when cited as relevant by experts, real estate agent and agency responses and the experts’ explanations.

Newsday shares the findings with you our readers to help illuminate an American ideal that is powerful in its simplicity — everyone deserves a fair shot at making a better life. That is a cornerstone to creating a stronger, more inclusive and more tolerant place to live for all of us.

– Deborah Henley, Editor

The findings are the product of a paired-testing effort comparable on a local scale to once-a-decade testing performed by the federal government in measuring the extent of racial discrimination in housing nationwide.

Regularly endorsed by federal and state courts, paired testing is recognized as the sole viable method for detecting violations of fair housing laws by agents.

Two undercover testers – for example, one black and one white – separately solicit an agent’s assistance in buying houses. They present similar financial profiles and request identical terms for houses in the same areas. The agent’s actions are then reviewed for evidence that the agent provided disparate service.

Newsday conducted 86 matching tests in areas stretching from the New York City line to the Hamptons and from Long Island Sound to the South Shore. Thirty-nine of the tests paired black and white testers, 31 matched Hispanic and white testers and 16 linked Asian and white testers.

Newsday confirmed that agents had houses to sell when meeting with testers based on analyses provided by Zillow, the online home search site. Zillow draws an inventory of available homes daily from the Multiple Listing Service of Long Island, the computerized system used by agents to select possible houses for buyers. MLSLI said that it does not maintain its own database of past daily inventories, as Zillow does, and so could not provide the same type of tallies. As permitted by law, all tests were recorded on hidden cameras to ensure accuracy in describing interactions between agents and customers.

Newsday relied on two nationally recognized experts in fair housing standards to evaluate the agents’ actions. The consultants were:

- Fred Freiberg, who co-founded the Fair Housing Justice Center in 2004. Previously, he had led a national testing program for the Civil Rights Division of the United States Department of Justice, as well as two national paired testing programs for the Urban Institute. He has coordinated more than 12,000 fair housing tests. He was paid to help organize the testing and train the testers but was not paid to evaluate test results.

- Robert Schwemm, the Everett H. Metcalf Jr. Professor of Law at the University of Kentucky College of Law. Schwemm is the author of “Housing Discrimination: Law and Litigation,” widely accepted as the definitive treatise of the subject. Schwemm assisted on an unpaid basis.

Newsday separately gave Freiberg and Schwemm summaries of tests that preliminarily appeared to show evidence of unequal treatment; transcripts of relevant remarks made by agents; and maps of the listings suggested to testers, along with the average percentage of white population in the census tracts where the listings fell.

An agent’s actions were deemed worthy of citing only after both consultants independently saw evidence of fair housing violations in response to the information provided by Newsday. While their opinions do not represent legal findings, their matching independent judgments provided a measure of apparent disparate treatment by the tested agents.

In fully 40 percent of the tests, evidence suggested that brokers subjected minority testers to disparate treatment when compared with white testers with inequalities rising to almost half the time for black potential buyers.

Black testers experienced disparate treatment 49 percent of the time – compared with 39 percent for Hispanic and 19 percent for Asian testers.

In seven of Newsday’s tests – 8 percent of the total – agents accommodated white testers while imposing more stringent conditions on minorities that amounted to the denial of equal service between testers.

“This is something that didn’t happen in the deep South,” said Greg Squires, professor of public policy at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., who offered advice about structuring the testing program.

“It happened in one of the most educated, most liberal regions of the country. These are significant numbers.”

Most commonly in the seven cases, agents refused to provide house listings or home tours to minority testers unless they met financial qualifications that weren’t imposed on white counterparts.

“I won’t do it,” Signature Premier Properties agent Anne Marie Queally Bechand said in refusing to take a black customer to tour houses unless the customer produced evidence that a lender had preapproved a mortgage loan.

One month earlier, Queally Bechand had asked a white customer who had yet to secure mortgage preapproval, “When can you start looking at houses?”

In nearly a quarter of the tests – 24 percent – agents directed whites and minorities into differing communities through house listings that had the earmarks of “steering” – the unlawful sorting of home buyers based on race or ethnicity.

One example: Amid MS-13 gang murders in Brentwood, a 79 percent Hispanic and black community, Le-Ann Vicquery, at the time a Keller Williams Realty agent, told a black customer:

“Every time I get a new listing in Brentwood, or a new client, I get so excited because they’re the nicest people.” She emailed the paired white customer: “please kindly do some research on the gang related events in that area for safety.”

Seven weeks after publication, Vicquery told Newsday she had not been fully aware of the gang violence when she spoke to the black customer, despite widespread media coverage. Vicquery said that she later warned the white customer because she had heard a gang-related story on television or radio on the day she escorted the customer on house tours. Queally Bechand did not respond to requests for comment.

Over the course of Newsday’s testing:

Altogether, agents provided white testers an average of 50 percent more listings than they gave to black counterparts – 39 compared with 26.

There was no such gap in paired testing for other minorities. Agents gave both Hispanic and white paired testers an average of 42 listings. Asians received 18 compared with 22 given to paired white testers. The averages include cases in which agents provided no listings to one or the other customer.

In some cases, agents keyed on the racial, ethnic or religious makeup of communities when speaking with testers, in all but one sharing the information only with white customers.

Fair housing standards generally bar agents from talking about the backgrounds of people who live in neighborhoods as a form of verbal racial or ethnic steering. The standards also require agents to provide equal guidance to customers about areas in which they may want to live. Century 21 agent Raj Sanghvi, for example, warned a white tester about buying in Huntington, a mainstay of northern Suffolk County.

“But you don’t want to go there. It’s a mixed neighborhood,” Sanghvi said, adding, “You have white, you have black, you have Latinos, you have Indians, you have Chinese, you have Koreans; everything.”

Sanghvi made no similar remarks to an Asian tester and suggested no Huntington houses to either tester.

Speaking to a white tester about one overwhelmingly minority community, RE/MAX agent Joy Tuxson promised, “I’m not going to send you anything in Wyandanch unless you don’t want to start your car to buy your crack, unless you just want to walk up the street.”

Talking to an Asian tester about another largely minority area, Tuxson said she had told a family member, “Do you really want your future children going to Amityville School Districts?”

Sanghvi and Tuxson did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

To capture broad swaths of Long Island, Newsday divided most of Nassau and much of Suffolk into 10 zones that included housing markets with affordable homes as well as million-dollar mansions and places where large groups of minorities live closely to white populations. The zones ranged from western Nassau to the Hamptons.

Newsday conducted tests in each zone and plotted the housing choices made by agents in each area, often revealing the communities they favored for buyers of varied backgrounds.

Cumulatively, the 10 zones encompassed 83 percent of Long Island’s population, including 80 percent of the white population and 88 percent of the minority population.

Mapping the listings by test zones

Overall, the agents gave black customers their smallest share of listings in towns with the highest proportions of white residents and their biggest share where whites were less prevalent.

Where whites composed 20 percent or less of the population, agents provided seven out of 10 listings to minorities. Only when whites hit 56 percent of the population did agents give most of the listings in a community, 63 percent, to whites.

Agents and brokers bear the responsibility for applying fair housing standards as they act as licensed gatekeepers to housing choices. Industry representatives have contended that proper training is the best way to ensure agents uphold fair housing laws, arguing against more aggressive enforcement through fines, license suspensions or revocations.

To assess the quality of training, Newsday attended six fair housing classes sponsored by the Long Island Board of Realtors. Experts who reviewed the instruction found that only one covered the material adequately and that others were “shockingly thin in content.”

After the testing was completed, Newsday revealed to testers for the first time how their counterparts had fared in visiting agents. The testers heard the comparisons sitting side by side – black beside white, Hispanic beside white, Asian beside white.

Often, they said the test results brought to light evidence of discrimination that had been hidden behind the smiles and handshakes offered by guides to housing in a suburb where the racial lines between many communities are starkly drawn.

Martine Hackett, who is black and a tenured professor of public health at Hofstra University, had met with seven agents and encountered evidence of disparate treatment three times. Her thoughts encapsulated the perspectives of many fellow testers.

“I would have no idea that, without this testing, that there was even a difference between what was provided. My assumption would be that everybody would be provided with the same listings based on their economic and geographic requirements,” Hackett said, adding:

“To sort of have the options to be limited in that way sort of makes me think about what options are available that people might not know about. And who’s making those choices? That’s the other thing that I feel, is that the choice, in terms of the choice of what would be theoretically the best choice for me and my family, was sort of removed.”

Another tester, Alex Chao, an actor who is Asian, learned that an agent had declined to provide him listings of houses for sale, a first step in a home search, but had given listings to his matched white tester. He called the difference in treatment deeply disturbing.

“I don’t think I was treated fairly at all,” he said. “That’s pretty outrageous and, of course, offensive, upsetting to find out. You know you read about these things, you never think they would happen to you.”

Newsday’s investigation focused on 12 brands that represented more than half of the Island’s home sellers in 2017.

They included Douglas Elliman, Century 21 Real Estate LLC, Charles Rutenberg Realty Inc., Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage on Long Island, Coach Realtors, Daniel Gale Sotheby’s International Realty, Laffey Fine Homes, Keller Williams Realty, The Corcoran Group, Signature Premier Properties, Realty Connect USA and RE/MAX LLC.

Tests of agents associated with two of the firms–The Corcoran Group and Daniel Gale Sotheby’s–produced no evidence of disparate treatment.

Newsday notified the 93 agents by letters that they had been tested and recorded. When Newsday’s two fair housing consultants found evidence suggesting disparate treatment, the letters detailed the facts so agents could review their records, specified the findings, gave agents the opportunity to view videos of their actions and invited them to provide their perspectives in interviews or written statements.

Additionally, Newsday delivered the identical information and opportunities for discussion and comment to the agents’ corporate leaders.

Thirteen agents and 21 corporate representatives came to Newsday and viewed materials for 26 paired tests that involved eight agencies.

Ultimately, fair housing violations are determined by the courts or enforcement agencies. Authorities may choose to file charges based on egregious conduct in a single case. More generally, they bring legal action after subjecting an agent to several paired tests to establish a pattern and to reduce the likelihood that an agent’s choices were either a fluke or soundly guided by the market at the time.

Newsday tested each agent only once. Falling short of proving legal wrongdoing, each result points to evidence of neutral or disparate treatment in a single comparison of customer contacts and offers little insight into an agent’s general professional conduct.

Collectively, however, the individual test results, bolstered by the statistical findings, form a body of evidence suggesting the extent of discriminatory practices by agents in Long Island home sales. Additionally, read side by side, the matched transcripts uniquely revealed the hidden disparities experienced by minority house hunters without their ever knowing they had been disadvantaged.

Editorial: Segregation’s stain can be overcome

Fair housing laws bar agents from directing whites to one community and equally qualified blacks, Hispanics or Asians to other places, a practice known as steering.

Even so, in 21 of 86 Newsday tests – 24 percent – agents located white and minority house hunters in areas that were different enough to suggest evidence of steering.

Elmont, a predominantly minority community, was suitable for a Hispanic house hunter but not for a comparable white one.

Freeport, an overwhelmingly minority village, could be a good place for a black home seeker but was a risky place to invest for a matching white tester.

Predominantly white Levittown was fit for a white buyer but more diverse East Meadow and Hicksville were appropriate for an African American.

Said one agent when speaking to a white customer: “I don’t want to use the word steer, but I try to edu – I use the word – I educate in the areas.”

Pointing out a need to study who lived in a community before buying, that agent, Rosemarie Marando of Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage, advised the customer to observe nighttime patrons of convenience stores.

“Wherever you’re going to buy diapers, you know, during the day, go at 10 o’clock at night, and see if you like the area,” she said, adding:

“There was one fellow who would – like insisted on this house, and the wife was pregnant and had a little one, and I said to him, ‘I can’t say anything, but I encourage you, I want you to go there at 10 o’clock at night with your wife to buy diapers. Go to that 7-Eleven.’ They didn’t buy there.”

“I have to say it without saying it, you know?” Marando confided.

She also counseled: “What I say is always to women, follow the school bus. You know, that’s what I always say. Follow the school bus, see the moms that are hanging out on the corners.”

Finally, Marando remembered hearing similar advice from an agent as a first-time homebuyer three decades ago and thinking, “What a creep.”

Marando made no similar comments when visited by a black tester. She gave both testers comparable listings in similar areas, showing no evidence of steering.

Newsday’s two fair housing consultants found that Marando had used “coded language” or “a euphemism” to describe steering while talking only to the white tester.

Based on information provided by Newsday, Robert Schwemm, law professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law, concluded:

“This agent knows what steering is and has come up with a euphemism for it that she is willing to share only with the white tester, not the black tester.

“Instead of ‘steering,’ she uses ‘location.’ She is saying she learned over time that this is particularly important. She is now displaying the behavior she criticized in her original agent. And not saying the same things to the black homebuyer is really problematic. Does she think minorities don’t want that?”

Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, concluded:

“This agent appeared to use coded language to urge the white tester to consider the racial composition of neighborhoods when considering where to buy a home.

“The agent said, ‘Look at who’s on the school bus. Look at who’s buying diapers in the grocery store.’ These statements were not made to the African American tester.

“While both testers were provided home listings in predominantly white areas, some of the statements made by the agent suggest that the agent is not interested in taking buyers to racially diverse neighborhoods.”

Newsday notified Marando of its findings by letter and email, invited her to view recordings of meetings with testers and requested an interview. She did not return phone messages.

Newsday presented its findings by letter to Charlie Young, president and chief executive officer of Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage. The letter covered the actions of Marando and additional Coldwell Banker agents.

The company’s national director of public relations, Roni Boyles, wrote in an emailed statement:

“Incidents reported by Newsday that are alleged to have occurred more than two years ago are completely contrary to our long term commitment and dedication to supporting and maintaining all aspects of fair and equitable housing.

“Upholding the Fair Housing Act remains one of our highest priorities, and we expect the same level of commitment of the more than 750 independent real estate salespersons who chose to affiliate with Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage on Long Island. We take this matter seriously and have addressed the alleged incidents with the salespersons.”

Coldwell Banker declined to discuss the company’s responses to specific cases.

A map of the 5,763 house listings gathered by Newsday represents the collective choices made by the tested agents. All things being equal, white and minority listings should appear in roughly 50-50 proportions across the Island.

They did not.

The map revealed divided racial and ethnic patterns that would help shape both lives and communities, in some cases speeding demographic change and in others blocking it.

Most stark: Agents directed white buyers most heavily to areas with the highest white concentrations while most often suggesting that black buyers focus on areas with lower white representations.

“They’re putting you in a place that they think you belong. They’re telling you that you don’t belong on this side of town because of your race or whatever and it’s not right,” said black tester Johnnie Mae Alston, a retired state worker, adding:

“But just because you think I would rather be here or because I’m a certain race you think that I should be over here. But what about my choices of where I want to live?”

Both blatant and widely accepted before the civil rights revolution, racial steering by real estate agents has receded largely from view.

Where agents once openly shut black buyers out of white communities, some now apply courteous professionalism while sorting buyers based on race or ethnicity.

“The issue of discrimination is very subtle,” said Claudia Aranda, a director of field operations for the Urban Institute, a nonprofit group that oversaw more than 8,000 paired tests in a nationwide study sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2010.

That study found real estate agents engaged less frequently than in the past in more explicit forms of discrimination, such as not showing available houses to minority buyers. However, the study also showed that agents placed minority buyers in more integrated neighborhoods at a higher rate than white buyers.

“In the absence of treatment that’s more overt, in the absence of particular discriminatory comments, individual home seekers will never have potentially any reason to suspect discrimination,” Aranda said.

Newsday’s tests sought to get behind the smiles and handshakes that can mask evidence of steering by comparing how agents responded to paired buyers while video recorders were running.

See evidence of steering

Thirty-nine times, black men and women engaged with real estate agents as paired undercover testers in Newsday’s investigation. In 19 of those times, the testing suggested they experienced disparate treatment compared with matched white testers. Additionally, one agent warned white and Asian testers to avoid predominantly black communities.

Kelvin Tune, 54, a federal employee, met with nine courteous, professional agents. He had no idea that seven of those meetings produced evidence of unequal service, with one agent in effect shutting him out of considering houses in the bedrock Long Island community of Plainview.

“I wasn’t welcomed to Plainview for her,” said Tune on learning the results of that test.

Johnnie Mae Alston, 65, a retired state worker, had no idea that an agent refused to provide her service on the same terms offered to a white client.

“I would have never known,” Alston said on learning how her experiences as a tester in Newsday’s investigation compared with the experiences of her white counterparts.

Speaking of the real estate agents she met, Alston added: “They make you feel like they are treating you like everybody else. That’s because you don’t see the other side. But once you see the other side, you realize that you aren’t treated that well.”

All these testers – both minority and white – discovered for the first time how their experiences compared when Newsday brought them together for joint interviews.

Testing found evidence that:Black testers experienced unequal treatment

49% of the time

- Newsday’s black testers experienced

disparate treatment at higher rates than did Hispanic (39 percent) and Asian testers (19 percent).

- In 11 cases, agents directed black testers to different neighborhoods than white testers in comparisons that showed evidence of steering.

- In five instances, agents imposed conditions on black testers that amounted to the denial of equal service compared with conditions requested of white testers.

- In three cases, agents either spoke about steering to the white tester but not the black tester or volunteered information about the ethnic makeup of communities only to white testers.

- Altogether, agents provided white testers an average of 50 percent more listings than they gave to black counterparts – 39 compared with 26, including instances when agents provided no listings to one tester.

There was no such gap in paired testing for other minorities. Agents gave both Hispanic and white testers an average of 42 listings. Asians received 18 compared with 22 given to white testers.

Limiting choices can help guide buyers toward and away from communities.

“Probably the most powerful tool for steering is through information withholding,” said Jacob Faber, an assistant professor of sociology at New York University who studies segregation.

“So that job as information conveyors is just really important.”

Before the changes driven by the civil rights movement, real estate agents often refused outright to serve black buyers. Today, experts say discrimination more likely takes the form of subtly directing buyers of different backgrounds toward different communities or requiring minorities to overcome higher financial barriers than whites.

Following are four case histories that show evidence of the disparate treatment hidden in house hunting while black on Long Island a half century after passage of the federal Fair Housing Law. They are accompanied by the findings of fair housing consultants Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, and Robert Schwemm, professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law.

The opinions of Freiberg and Schwemm are based on data provided by Newsday. Their judgments are not legal conclusions.

The case histories also include the responses of agents and the companies they represent.

TEST 67An agent suggests five Plainview homes to a white house hunter – but tells a black home buyer that houses with the same market value there are out of his price range.

TEST 76 An agent takes a white customer on house tours without requesting identification – but asks a black house hunter to show ID.

TEST 96 An agent warns a white home buyer about gang violence in Brentwood – but directs the black house hunter toward the predominantly minority community.

TEST 45 An agent warns a white customer to avoid investing in Freeport – but suggests the predominantly minority village could be a good choice for a black customer.

Explore the test cases

Serving as gatekeepers to homes, schools and communities, some real estate agents made the key to the front door easier to reach for whites than for minorities.

Typically, these agents provided ready service to white customers they encountered in Newsday’s investigation, offering homes to consider and conducting house tours while taking on faith that the white house hunters had the financial capability to purchase.

In contrast, they denied similarly full service to minority customers, refusing to provide listings or tours unless the customers showed proof of financial capability.

In seven of Newsday’s 86 paired tests – 8 percent – the agents’ conduct produced evidence of unequal treatment amounting to the denial of equal service to minorities.

Black buyers experienced the evident denials most frequently – in five of the tests. One tester was Hispanic. One was Asian.

The five tests that produced evidence of the denial of equal service to black testers occurred among 39 black-white tests – a rate of almost 13 percent.

No agent in any test placed greater obstacles in front of a white buyer than a matched minority customer.

Posing as first-time home buyers, white and minority testers separately asked agents to start their searches by suggesting house listings and by providing tours of properties for sale. No agent flatly refused service to anyone.

Instead, seven agents imposed conditions on minority buyers that were seemingly reasonable until matched against service they provided to white buyers.

One condition involved securing preapproval or prequalification for a mortgage loan. Preapproval certifies that a lender has found a buyer creditworthy up to a certain amount based on a credit check and documentation submitted by the buyer. Prequalification indicates that a lender has preliminarily offered a similar judgment without yet conducting a full financial review.

Another condition entailed granting an agent the exclusive right to represent a buyer. Exclusive broker’s agreements stipulate that an agent will be a buyer’s sole representative and typically guarantee that the agent will be paid a commission, either from the proceeds of a sale or directly by a buyer.

The law permits agents to employ both stipulations equally with all customers. But it bars agents from imposing them only on members of one group and not another.

One example: Although a black customer told Laffey Real Estate agent Nancy Anderson, “My uncle is actually a loan officer so we crunched the numbers with him,” Anderson refused to provide house tours, emailing, “I need to have the preapproval before we see the listings.”

TEST 92

In contrast, she escorted a paired white buyer on house tours after he assured her, “I got a buddy of mine that works at Roslyn Savings & Loan.”

Anderson did not respond to a letter informing her of Newsday’s findings or to invitations by letter and email to view video recordings of her meetings with testers. When reached by telephone, she said, “I have no comment to you at this point.”

Mark Laffey, named on Laffey Real Estate’s website as principal owner, and Philip Laffey, described as overseeing Laffey Real Estate, did not respond to letters, emails and telephone calls requesting interviews or comment.

Experts say real estate agents may more efficiently manage their time if they require buyers to produce a mortgage preapproval or a prequalification letter before providing house listings or taking the customers out on a tour.

“If you are really worried about your time, you’d require everybody to be prequalified,” said Dorothy Brown, a law professor at Emory University School of Law who focuses on issues of race and legal policies.

“White people get turned down for mortgages too, so why wouldn’t you?”

Based on facts presented to them in Anderson’s case, Newsday’s two fair-housing consultants, Fred Frieberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, and Robert Schwemm, professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law, saw evidence of unequal treatment.

Freiberg wrote: “The agent’s refusal to provide service to the African American tester is an example of disparate treatment based on race. The agent told the African American tester that a preapproval letter was a condition of being shown homes but did not impose this same condition on the white tester.”

Schwemm concluded: “Evidence of blatant discrimination (inferior treatment of the black tester) regarding not showing houses before receiving a preapproval letter.”

Newsday’s tests compared how agents interacted with people of different races or ethnicities in individual situations and therefore may not necessarily shed light on how any individual agent treats white and minority customers in general.

As one illustration, Realty Connect USA agent Reza Amiryavari provided service to black and white customers without preconditions in a test that Newsday disqualified because recording equipment failed. In a subsequent test, Amiryavari required a Hispanic buyer to meet conditions that indicated a denial of equal service when compared with the white buyer.

Reflecting on what she had learned from serving as a tester, Brittany Silver, who is white and an actress, said:

“A Caucasian person with money coming in to spend it really could never do anything wrong.” She added: “I don’t think that person will ever be questioned. I think that I am privileged because I’m white.”

Following is evidence of disparate treatment at work in four case histories, as affirmed independently by consultants Frieberg and Schwemm, who rendered similar judgments on all seven tests that produced evidence of the denial of equal service to minorities.

The opinions of Freiberg and Schwemm are based on data provided by Newsday. Their judgments are not legal conclusions.

The case histories also include responses of agents and the companies they represent.

TEST 93 An agent refuses to show homes to a black buyer unless the buyer signs an exclusive broker’s agreement – just hours before she invites a white buyer on house tours without requiring such an agreement.

TEST 30 An agent offers to drive a white house hunter to tour homes, provides 79 listings and escorts the potential buyer to see four houses without proof of financial standing. The agent tells a black home seeker she must produce mortgage prequalification.

TEST 78 An agent tells a Hispanic house hunter that he helps customers only after they sign an exclusive broker’s agreement and secure mortgage preapprovals. The agent provides listings and tours to a white house hunter without requiring either document.

TEST 09 An agent tells black and white house hunters that he provides listings and home tours only to customers who have mortgage preapproval – then bends his stated policy for the white potential buyer.

Explore the test cases

Real estate agents associated with Long Island’s biggest brokerages had more than 200 opportunities to suggest houses to paired testers in eight overwhelmingly black and Hispanic communities during Newsday’s fair housing investigation.

The agents largely avoided the minority communities, recommending homes there only 15 times. But when they did offer listings in minority communities, they sent those listings more often to minority buyers than to whites.

Freeport, Elmont, Hempstead, Brentwood, Central Islip, Uniondale, Roosevelt and Wyandanch fell 211 times within the home search areas presented by testers to agents – for example, 30 minutes from Hempstead at a top price of $450,000 or 20 minutes from Brentwood at a $475,000 maximum.

The eight predominantly minority communities ranged from 73 percent minority Freeport to 97 percent minority Roosevelt. Although houses were on the market with prices that ranged from $400,000 to $500,000, the agents directed all but a small share of testers to communities with larger proportions of white residents.

“I think what you’ve described is steering based on racial composition of a neighborhood. The fact that everybody is steered away doesn’t make it acceptable,” said Greg Squires, a professor of public policy at George Washington University in Washington who has served as a consultant to fair housing groups and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“You could argue that this does not show discrimination against the home seekers because everybody was steered away from these neighborhoods,” Squires added. “If in fact that’s the case, what it suggests is discrimination against certain neighborhoods because of the racial composition of those neighborhoods.”

Newsday tested agents who worked with the 12 companies that dominate the market: Douglas Elliman Real Estate, Century 21 Real Estate LLC, Charles Rutenberg Realty Inc., Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage on Long Island, Coach Realtors, Daniel Gale Sotheby’s International Realty, Laffey Fine Homes, Keller Williams Realty, The Corcoran Group, Signature Premier Properties, Realty Connect USA and RE/MAX LLC.

Altogether, they have 218 branch offices in Nassau and Suffolk counties but no offices in the eight communities where most of the Island’s racial minorities live. The average white population in the towns where the top real estate brands have their offices ranges from 75 percent (Century 21) to 86 percent white (Keller Williams).

Asked by letter why they have no presences in the Island’s predominantly minority communities, representatives of only three of the 12 companies responded: Daniel Gale Sotheby’s, Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage on Long Island and RE/MAX LLC.

Katherine Heaviside, a spokeswoman for Daniel Gale Sotheby’s, said the firm had “grown over the years to over 28 locations. While we are not in every community, we look forward to expanding into many more locations in the years to come.”

Spokeswomen for Coldwell Banker and RE/MAX noted that with the technology available today, customers can connect with agents’ services without having to go to a physical office.

The RE/MAX representative, Kerry McGovern, said the company operated a franchise in Freeport from 2000 to 2010 and in Hempstead from 2005 to 2017.

McGovern also said: “We do not share actual figures of this nature but can confirm RE/MAX agents have had many listings and have closed transactions in each and every one of these neighborhoods in the past year.”

Coldwell Banker spokeswoman Roni Boyles said the firm’s “market share has steadily increased year over year from 2016 through 2018 collectively, in the communities you named: Elmont, Freeport, Hempstead, Roosevelt and Uniondale.”

The 12 biggest firms on average have had a smaller market share in the eight minority communities than they do across the Island. They’ve controlled more than half the listings Islandwide. But in the minority communities, the biggest firms’ market share has ranged from about a fifth in Wyandanch to a third in Freeport and Elmont.

Agents associated with smaller, locally based brokerages service most of the listings in the eight minority communities.

Roy Clark, an agent with LI Community Realty Inc. in Brentwood, said large brokerages overlook areas like Brentwood, Central Islip and Wyandanch.

“They don’t really make advances here,” said Clark, who has worked in the area for nearly 15 years.

When agents from the larger firms have contacted him about showing a house hunter one of his listings, Clark added, “I have not experienced any white buyers at all being brought by any large company.”

Clark said when he used to work at one of Long Island’s largest brokerages, “they didn’t really venture too much into areas that were areas of color. I don’t know if it was a fear factor or what. I don’t know why they didn’t.”

Lenora W. Long, a broker based in Hempstead for 18 years, said she has noticed trends like those experienced by Clark: white agents working for the Island’s biggest firms contacting her about her listings in Hempstead on behalf of a black or Hispanic client.

“I’ve never had the experience of an agent from the North Shore or South Shore bringing a Caucasian looking for a home in Hempstead,” Long said. “It’s usually black or Hispanics shuttled into Hempstead.”

Jim Blais, who is white and a resident of Hempstead Village’s Ingraham Estates development, said he has witnessed the phenomenon described by Long.

“There are roughly five houses in the last two or three years that have gone for sale or have been sold and what I’ve noticed is that you see only black or Hispanics coming to look at the houses,” Blais said. “I have yet to see a white family coming by.”

See how it affects communities

Pedro Jimenez expected to find evidence of some discrimination as a Hispanic searching for a home on Long Island. He found more than he imagined as a member of the Island’s largest minority group.

Jimenez asked eight real estate agents for help buying houses as a paired tester in Newsday’s investigation of discrimination in real estate sales. Five of the eight tests produced evidence that agents had subjected Jimenez to unequal treatment when compared with his white counterparts.

“It is alarming. It is crazy,” he said. “It’s 2018, I cannot stress that enough – this is 50 years after the civil rights marches. I remember all sorts of people saying, well, we’re post racial, we voted a black president. No, we’re not. Obviously, we are not.”

Jimenez, 45, is a computer and internet professional who was born in the Dominican Republic.

As a boy of 5, he followed his mother to immigrate legally to the United States. He grew up in the Corona section of Queens, attended New York City public schools and helped his mother earn income by making belts in the family’s apartment.

Jimenez also remembers that the social surroundings taught him to distinguish between light-skinned and dark-skinned fellow Hispanics, those of darker tones being looked down upon.

The milieu also included attitudes toward women and gays that he long ago grew to consider backwards.

“I’ve been everything. I’ve been the misogynist. I’ve been the racist. I’ve been the homophobe. Over time I just came to learn almost in evolutionary steps there is no basis for those things,” Jimenez said. “You don’t know these people, how can you cast this light on people you don’t know? And not only that, but by having this view I am causing this suffering.”

That evolution, Jimenez believes, outpaced the attitudes of real estate agents he encountered as an undercover tester.

“What this says to the Latino population is that, clearly, you’re going to be steered, especially if you leave yourself at the mercy of the agent,” he said.

Latinos compose 18 percent of the Island’s population, according to 2017 census estimates, followed by blacks at 9 percent and Asians at nearly 7 percent. They are spread widely, with 90 percent of the population living in 120 of the Island’s 291 communities. The United States Census Bureau defines Hispanics and Latinos as people of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race.

Jimenez was one of five Hispanic testers who went undercover in Newsday’s investigation.

They engaged with agents representing 12 of the Island’s largest brokering firms in offices located from Massapequa Park, Brentwood and East Hampton on the South Shore to Great Neck and Northport on the North Shore. Using aliases with Hispanic surnames, they said they were looking for houses with prices that ranged from $400,000 to $3 million.

All told, Newsday’s:five Hispanic testers met evidence of disparate treatment

39% of the time

Jimenez, Ashley Creary, Nana Ponceleon, Liza Colpa and Jesus Rivera went house hunting 31 times while paired with matching white testers. Twelve of the tests showed evidence that agents:

- Provided the group 12 percent fewer listings than the white buyers in those tests, with the gap larger in the overwhelmingly white communities of Rockville Centre, Oceanside, Roslyn, Levittown, Merrick and Kings Park. There, the agents gave white testers seven times more homes to consider than they provided to matching Hispanic testers.

- Focused Hispanic testers on houses in 18 census tracts in the Town of Huntington that took in the downtown area, then stretched north to Halesite and south to Huntington Station, South Huntington and West Hills. They picked listings in these areas for Hispanic testers at double the rate they did for white buyers. Eleven of the 18 tracts show growing Hispanic populations.

- In one case, imposed more stringent requirements on a Hispanic tester than a white buyer, amounting to a denial of equal service, according to evaluations by Newsday’s fair housing consultants.

Following are three case histories showing evidence that Hispanic house hunters experienced disparate treatment, along with the findings of Newsday’s fair housing consultants Fred Freiberg and Robert Schwemm.

The opinions of Freiberg and Schwemm are based on data provided by Newsday. Their judgments are not legal conclusions.

The case histories also include the responses of agents and the companies they represent.

TEST 42An agent complains to a white house hunter that fair housing laws bar him from warning buyers away from certain communities, offers the customer choices in predominantly white areas and directs a Hispanic house hunter to predominantly minority communities.

TEST 07 An agent tells a white buyer that she would look in areas that surround a predominantly minority community while telling the Hispanic buyer that she would concentrate more on that community.

TEST 87An agent tells a white customer that he “might be more comfortable in a certain demographic area,” says she is barred from talking about demographics – but adds her colleague will educate the customer, whom she describes as a “stand-up guy.”

Explore the test cases

While searching for homes with prices ranging from $400,000 in the Bay Shore and West Islip area to $7 million on the North Shore Gold Coast, Asian house-hunters met evidence suggesting discrimination less often than black and Hispanic peers in Newsday’s paired testing of real estate agents.

The Asian would-be home buyers – one Chinese American, one Korean American, one South Asian American – participated in 16 tests that measured the service agents gave to them against how the agents helped comparable white buyers.

In all but three, agents provided comparable service to Asian and white house hunters. The three exceptions included evidence that one agent denied equal service to an Asian tester compared with his white counterpart and that two agents provided greater information about communities to white testers – even as the agents disparaged those areas.

None of the tests matching Asian and white buyers showed evidence that agents had steered house hunters to different communities.

At three out of 16 tests, the individual Asians experienced evidence suggesting discrimination 19 percent of the time – a frequency far less then met by black (49 percent) or Hispanic (39 percent) testers.

That rate reflected apparent personal discrimination against Asian testers. Two additional tests suggested possible violations of fair housing standards that restrict agents from volunteering the racial, ethnic or religious makeup of communities to customers. In those two tests, agents pointed out a growing Asian presence in an area to potential white buyers.

“It would probably always be questionable to raise those kinds of matters if the home seeker didn’t ask about them,” said Robert Schwemm, a professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law and authority on the fair housing act, who served as Newsday consultant. “There is clear law that says steering can occur based on statements about racial makeups that are unsolicited by the home seeker.”

Explore the test cases

Clustered in northern Suffolk County, more than an hour’s commute by train to Manhattan, Huntington and its adjoining communities have long epitomized Long Island’s suburban lifestyle. There’s a vibrant downtown. There are stately homes on wide leafy streets. There are former beach cottages close to Long Island Sound.

And there is change: The white population has dropped in many census tracts, and the Hispanic population has risen – a phenomenon reflected in house choices by real estate agents in Newsday’s investigation of residential sales practices.

The area emerged as the location most favored by agents for Hispanic house hunters on Long Island. In undercover testing that paired white and Hispanic buyers, agents recommended the Huntington surroundings far more often to the Hispanic testers – even though none asked specifically to live in that area.

In five tests, white and Hispanic house hunters sought $450,000 to $500,000 houses within 20 or 30 minutes of Greenlawn or Northport, two communities within driving distances from downtown Huntington, or a $600,000 house within 30 minutes of Syosset, an area also encompassing Huntington.

Collectively, the agents gave the testers 453 listings, recommending 65 percent of them to the Hispanic house hunters. The listings covered a swath of territory that extended from Plainview and Oyster Bay on the west to Hauppauge and Kings Park on the east.

Among those listings, the agents suggested homes in the core Huntington communities of Huntington, Huntington Station and South Huntington 173 times. Here the concentration of houses recommended to Hispanic buyers hit 84 percent – with no agent providing a majority of listings to a white tester.

The gap in the number of home recommendations made to Hispanic and white buyers in three of the tests was large enough that Newsday’s two fair housing consultants detected evidence suggesting that agents had steered Hispanic buyers into the Huntington area compared with matched white buyers.

These three agents recommended houses in the Huntington area 78 times to Hispanic house hunters and three times to their white counterparts – an imbalance of 96 percent for the Hispanic testers and 4 percent to the white testers.

In contrast, where agents chose Huntington as a place to live in six similar black-white tests, they recommended it to the black buyer 39 percent of the time.

Explore the test cases

No house hunter asked specifically to live in three Long Island communities where white residents dominate the population – but seven real estate agents specifically suggested them almost exclusively to white potential buyers during Newsday’s investigation.

Merrick, Levittown and Rockville Centre in Nassau County emerged in the testing as places that these agents overwhelmingly chose for the white customers but not for their matching, paired minority home seekers. The makeup of the communities ranges from 75 percent white to 88 percent white.

The agents’ choices matched the demographics of the towns: The seven gave their white customers 13 times more listings in the communities than they provided to matching minority buyers. Two suggested homes there only to their white customers.

In all seven tests, Newsday’s two fair-housing consultants – Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, and Robert Schwemm, professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law – independently detected evidence of steering.

See the evidence

In February 2016, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo invoked Martin Luther King Jr. as he announced a “groundbreaking” drive against discrimination in home sales and rentals.

The governor told an enthusiastic audience at the Convent Avenue Baptist Church in Harlem that the state would sponsor paired testing across New York – a technique that uses undercover investigators – to crack down on real estate agents and landlords who fail to treat white and minority customers equally.

“We’re going to investigate it,” Cuomo vowed. “We’re going to find it. We’re going to ferret it out. We’re going to punish it and we are going to prosecute it because it is illegal.”

Added Cuomo, who formerly served as secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development:

“There will be people who will be unhappy because it’s going to be disruptive to a lot of the big players in the housing industry who like it the way they now have it.”

Three years later, Cuomo’s unprecedented drive as governor – now described by his administration as a “pilot program” – entailed the expenditure of $65,000 and conducted 88 paired tests of upstate and Westchester-area landlords for discrimination in apartment rentals.

The results included a $6,000 fine against a landlord charged with refusing to rent to disabled individuals using emotional support animals; a $15,000 settlement by a landlord charged with refusing to rent to black applicants; and a pending court case against a landlord for allegedly refusing to rent to individuals who use service animals.

Cuomo, who as New York attorney general oversaw 200 tests of real estate industry practices, has not allocated funding for additional testing as governor.

The governor’s enforcement foray illustrates the cost of paired testing investigations, as well as the wide gap between their limited use and the documented prevalence of hidden discrimination.

In a summary of Cuomo’s actions to combat bias in housing, the governor’s office noted that he signed legislation this year banning discrimination based on source of income, such as housing subsidies or child support. In July, he directed the Department of Financial Services to investigate whether Facebook allows housing advertisers to discriminate.

A senior adviser to the governor also said the administration has investigated landlords to deter discrimination on the basis of immigration status and other factors.

“This administration takes housing discrimination very seriously and this Governor has enacted more protections against it than any other governor in history,” Rich Azzopardi, senior adviser to the governor, said in a written statement.

“Every complaint received is thoroughly investigated and we urge any New Yorker who believes they have been the victim of housing discrimination to contact us immediately.”

On paper, real estate agents are subject to investigation and discipline by multiple levels of government. But at each rung on the enforcement ladder, the agencies lack the capacity to use the primary tool for uncovering fair housing law violations by real estate agents.

Surveyed by Newsday, the executive directors of large nonprofit fair housing watchdogs that rely on government funding, including in Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, Miami, New Orleans, New York and Houston, unanimously said their budgets are too small to support sustained paired testing of discrimination among residential real estate agents.

Said Rodney H. McRae, executive director of the Nassau County Human Rights Commission, an agency that employs only a five-person staff and is located in one of America’s most segregated suburbs:

“We do not do any testing.”

Why testing is needed

The segregation of blacks and whites has been embedded on Long Island as firmly as the Meadowbrook Parkway.

Heading north from the South Shore bayfront, the six-lane road divides overwhelmingly minority Freeport from overwhelmingly white Merrick; then overwhelmingly minority Roosevelt from overwhelmingly white North Merrick; then overwhelmingly minority Uniondale from East Meadow, where seven of 10 residents are white.

A swath of asphalt, concrete, grass and trees framed by green space, the parkway forms a barrier between communities that are as little as 1 percent white and as little as 2 percent black. The demarcations are stark even as the road serves as a conduit for more than 70,000 cars daily.

Long Island has 291 communities Most of its black residents live in just 11

As one of the most segregated suburbs in America, Long Island is crisscrossed by racial barriers. Some, like the Meadowbrook, are visible. Some are the invisible product of historical forces including zoning regulations, mortgage redlining, the boundaries of 124 school districts, housing prices, and racial steering and blockbusting — a tactic used by real estate agents to drive up sales, and commissions, by inducing blacks to move into a white neighborhood and then warning whites that property values were about to plummet.

For three years, Newsday investigated real estate practices on Long Island using a testing system in which whites and minorities, acting as home seekers, were paired to gauge how real estate agents treated them. The probe found that white testers were shown neighborhoods with higher proportions of white residents than black testers were, while the black testers were shown homes in more integrated neighborhoods. It also showed that certain minority areas were largely overlooked for everyone.

The divides are taken for granted even in places where they dictate that black and Hispanic children will learn only with black and Hispanic children, and white children will learn only with white children, in elementary schools a mile apart.

After studying Long Island, Myron Orfield, director of the Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity at the University of Minnesota Law School, sees “hard racial barriers where black communities are next to white communities and they stay very firm.” Orfield adds: “On Long Island, there’s hard walls. It’s a tough, tough wall there. When you see those hard, differential walls, underlying that there’s usually bigotry and prejudice that’s maintaining those hard walls.”

Learn the history

Long Island real estate agents sell schools as much as houses.

School district ratings are among the most zealously watched indicators of quality of life by Long Island homeowners, not least because they can influence home values.

In many of Newsday’s 86 paired tests, agents applied a laser-like focus on districts, highlighting their perceived quality when recommending places that house hunters should consider buying – or avoid.

As one real estate agent explained it: “So, more important than Syosset is schools, because everything is by schools on Long Island.”

That reliance on school ratings as a top selling point can empower Long Island real estate agents to serve as gatekeepers for 124 highly delineated districts whose test scores, graduations rates and ethnic and racial compositions vary sharply. In playing the gatekeeper role, they risk running afoul of fair housing standards because discussing school quality can become a proxy for talking about a community’s makeup.

As the National Association of Realtors stated in a 2014 post on its website, “Discussions about schools can raise questions about steering if there is a correlation between the quality of the schools and neighborhood racial composition.”

Characterizations about schools with low test scores, for example, or comments that reference a “‘community with declining schools’ become code words for racial or other differences in the community,” the post states. As a result, such comments become “fair-housing issues.”

Additionally, fair-housing experts say touting or disparaging schools can put agents in legal jeopardy because many lack the expertise to make such judgments.

“Since when did real estate agents become experts on schools?” asked Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, who served as a Newsday consultant.

“It’s ridiculous because they cannot, they should not be trusted to provide objective information about schools and school performance rates,” Freiberg said.

“I might go into an area and maybe it’s not the highest scores I’m looking for for my son. Maybe it’s the music program. There could be a lot of different reasons why I would think a school was better or worse for my son that has nothing to do with test scores, certainly nothing to do with race.”

While some agents tested by Newsday told customers that they were legally barred from talking about schools, fair-housing experts say agents may provide information so long as it is strictly factual – and provided equally to customers.

The National Association of Realtors made clear that agents have a narrow pathway that involves sticking to “objective information,” not their personal opinions.

The author suggested that agents provide prospective homebuyers with school or community websites that provide ratings and data.

“The best thing a Realtor can do is guide them to third-party information, so they can make a decision on their own,” the post recommends.

Some agents touted districts as highly rated. Some denigrated districts as undesirable places to invest in homes. Whether based on facts or simply their own beliefs, some expressed perceptions about district performances that were in line with pointing buyers toward communities with substantial white populations and away from more integrated areas.

Examine how it’s done

State-required continuing education classes in real estate law and practices are supposed to cover fair housing regulations and how agents and brokers might deliberately or unintentionally discriminate.

Instead, in five of six classes attended by Newsday reporters, instructors provided information that was sometimes or often inaccurate, incomplete, confusing or lacking in quantity and quality, according to eight fair housing experts who reviewed transcripts and notes of the sessions.

Some instructors made comments about ethnic and religious groups that risked reinforcing discriminatory attitudes, the experts said. One instructor likened fair-housing laws to speed limits faced by a cab driver rushing a customer to the airport, telling students: “You get to choose whether you break the law.”

Other instructors filled class time with irrelevant material, such as reviews of television shows and descriptions of funeral rituals.

One described Rockville Centre as “lily white,” referred to West Islip as “white Islip” and used derogatory racial and religious terms.

Only one of the six classes included the required three hours of fair-housing law training.

The experts examined the transcripts of four classes in which instructors set no rules against recording or quotation. They also reviewed notes on one class where the instructor barred recording but placed no restrictions on quoting. The instructor in the sixth class said she did not want to be quoted.

The instructors included the president of the Long Island Board of Realtors and three former presidents, including one who is now an attorney for the board.

New York State law requires real estate agents to attend 22.5 hours of continuing education every two years to renew their licenses. The material must include the three hours of instruction in upholding anti-discrimination laws. The state permits up to 10 minutes of break time during each hour of instruction.

Many agents opt to take in-person classes to keep their licenses up to date. LIBOR reported 14,034 registrations for its own classes and 9,703 registrations for online classes in 2017, its most recent available tax filings show. To see how Long Island agents were trained, Newsday reporters registered online for in-person fair-housing classes offered by LIBOR.

“The trainers veered pretty far away from actually covering the important topics that a Realtor or real estate agent would need to understand in order to comply with their obligations,” said Thomas Silverstein, associate counsel with the Fair Housing & Community Development Project at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law in Washington, D.C., who reviewed transcripts and notes from three classes.

What happened at trainings

The young white man was an actor, the young black man a drug store worker. They were going undercover with constructed identities – new families, new ages, new addresses, new incomes, new jobs. The white man was cloaked as a building contractor, the black man as a piano tuner.

Married without children to a working wife with a household income of $125,000, their essential personas were interchangeable – except for the black-and-white distinguishing factor of race.

One month apart in the spring of 2016, each strapped a tiny camera to his chest with a miniature lens that peeked through a button hole of his shirt. Then, with the camera running, each separately met with one of Long Island’s 27,000 licensed residential real estate brokers and agents.

Posing as first-time house hunters in the spring of 2016, white actor Steven Makropoulos and black drug store worker Ryan Sett led a 25-member platoon of white, black, Hispanic and Asian New Yorkers into Newsday’s investigation of residential brokering.

Ordinary folks stocked the platoon: a 20-year-old college student, a 69-year-old lawyer, teachers, a computer tech, actors and more. All were recruited by Newsday to work as paired testers in the hope of measuring how often, if at all, agents provided unequal service to white and minority house hunters.

Collectively, they went undercover with agents for 16 months and recorded 240 hours of video in 109 tests conducted from April 2016 to August 2017. A professional court reporter created typed transcripts of the meetings between testers and agents. Newsday journalists reviewed the transcripts for accuracy and used them to verify that testers had, in fact, presented matching profiles to agents.

This is the story behind the three-year investigation.

Inside our investigation

Lead writers: Ann Choi, Keith Herbert and Olivia Winslow

Project editor: Arthur Browne

Reporters: Choi, Bill Dedman, Herbert and Winslow

Data analysis and visuals: Choi

Strategic planning and methodology: Dedman

Additional reporting: Maura McDermott and Deborah S. Morris

Contributors: Rachelle Blidner, Mark Harrington, Bart Jones, Carol Polsky, Chau Lam, David Olson and Nicholas Spangler

Project manager: Tara Conry

Assistant project manager: Heather Doyle

Data visuals and additional data reporting: Will Welch

Additional editing: Doug Dutton and Robert Shields

Video directors: Jeffrey Basinger and Robert Cassidy

Video editors: Basinger, Matthew Golub and Megan Miller

Videographers: Basinger, Raychel Brightman, Cassidy, Shelby Knowles, Alejandra Villa Loarca, Arnold Miller, Chris Ware and Yeong-Ung Yang

Aerial Photography: Basinger, Ware and Yang

Motion Graphics: Basinger

Media Management: Alexa Coveney, Golub and Greg Inserillo

Photography: Basinger, Cassidy, Knowles, Villa Loarca, Arnold Miller, William Perlman, Ware, Yang

UX design director Matthew Cassella

Digital design: Anthony Carrozzo, Mitch Severe and James Stewart

Director of development: TC McCarthy

Development: John Tomanelli and Will Welch

Homepage video: Miguel Cubillos

Additional project management: Anthony Bottan

Social media: Anahita Pardiwalla, Elaine Piniat

Digital Quality Assurance: Daryl Becker, Sumeet Kaur

Research: Caroline Curtin, Nyasia Draper, Dorothy Levin, Laura Mann and Judy Weinberg

Editorial support: Kim Fiorio

Copy editing: Don Bruce and Leema Thomas

Print graphics: Gustavo Pabón

Print design: Seth Mates