On its own, the 54-second cellphone video is unremarkable.

Two plainclothes Nassau police officers speak to a man holding a phone and straddling a laid-down bicycle. As the recording opens, the man, who is Black, insists to the officers, who are white, that he knows an assistant district attorney.

“I’m connected,” he says.

The officers, Peter Ellison and Carl Arena, had asked for the man’s last name. He didn’t provide it.

Barely audibly, Ellison says, “I think this is a discon,” short for disorderly conduct, a noncriminal violation.

“You’re under arrest, you won’t tell us your name,” Arena states, producing handcuffs and clasping the man’s left wrist. The man does not resist.

“…advised the Defendant that if he can not produce any form of identification he will be arrested.”

Disorderly conduct complaint filed against Hayes. Credit: U.S. District Court in Central Islip

“We’re trying to be nice to you,” Ellison says, moving the man’s right arm behind his back.

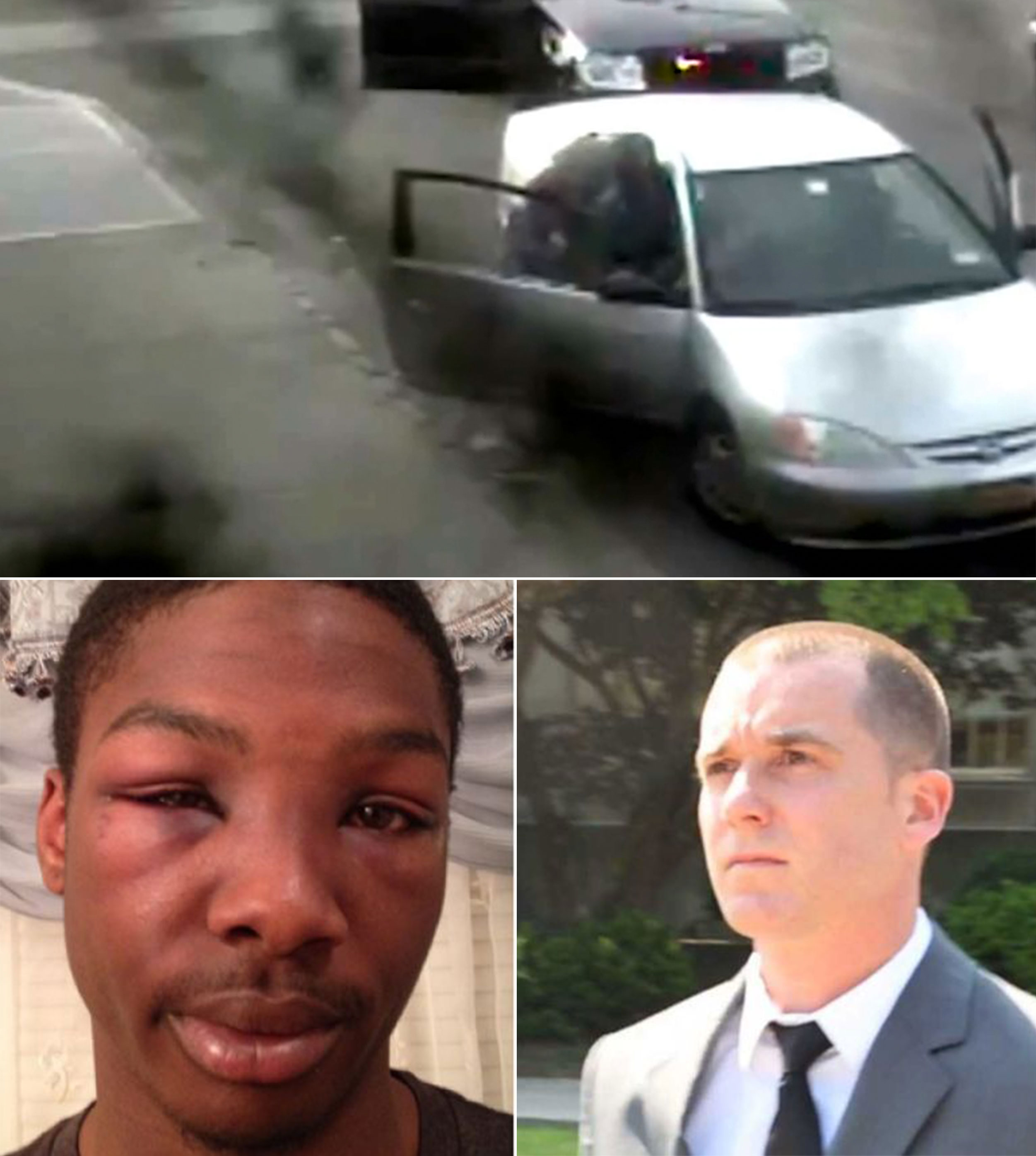

Again, the man offers no resistance. The officers use no force. The Uniondale barber who recorded the arrest from his shop’s rear doorway seems to be the only other person to fix on the encounter between the two officers and Bobby Hayes, a longtime Hempstead resident.

“I didn’t do nothing,” Hayes complains, glancing at the camera, as he’s being handcuffed and led away.

At a time when recordings of white police officers injuring or killing Black citizens have generated sustained protests against systemic racism in law enforcement, viewing the clip of Arena and Ellison arresting Hayes on Jan. 29, 2014, suggests no evidence of misconduct.

But matching the video against the paperwork filed by Arena and Ellison changes the picture.

Arena filed a statement that charged Hayes with disorderly conduct for, he wrote, yelling repeated profanities and racial epithets that drew spectators. Ellison charged Hayes with resisting arrest for, he wrote, physically struggling with the officers and refusing numerous commands to allow himself to be handcuffed.

Arena and Ellison also reported that Hayes had explicitly threatened their lives while on the way to, and at, the police precinct. The man’s lawyer, William Petrillo, said in court that the claim led to Hayes being shackled and held in 23-hour-a-day lockup for more than a week. That was before the video prompted the Nassau District Attorney’s Office to dismiss all charges, including a third accusation of noncriminal marijuana possession.

Cameras and consequences

Watch and ReadNewsday examined Hayes’ arrest as one of four case histories documenting how civilian video recordings have come into play in evaluating police actions at a time when the Nassau and Suffolk county police departments are among a small minority of large U.S. police forces that do not equip large numbers of officers with body cameras.

In three of Newsday’s case histories, including Hayes’, security or cellphone video captured evidence that contradicted police accounts, prompted judges and prosecutors to dismiss arrests and supported lawsuits that saddled taxpayers with paying more than $4.6 million in compensation so far.

Criminal justice experts concluded after reviewing the three cases for Newsday that the presence of body-worn cameras may have prevented officers from lodging charges that proved baseless. In a statement emailed through Petrillo, Hayes wrote that he believes a body camera would have prevented his arrest.

“The Defendant started to swing his arms and upper body and pull his arms away from the Officers and refuse to place his hands behind his back.”

Resisting arrest complaint filed against Hayes. Credit: U.S. District Court in Central Islip

“Had the officers been wearing one, I never would’ve been framed for something I didn’t do, treated like garbage, thrown into jail for nine days,” Hayes said. “None of this would’ve happened because the police would’ve known the camera showed everything, just like the video that they were unaware of does.”

The fourth case history demonstrated the limitations of interpreting police actions based on civilian videos, which can be taken at any distance or angle and generally do not include sound. Still, the recording captured the events that led the Nassau County Police Department to issue a wanted alarm based on false information. The events convinced a retired Suffolk lieutenant at the center of the case to call for body cameras as standard police equipment.

County leaders appear to be coming around to the idea. Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone in early March called for equipping large numbers of officers with cameras after one of the few devices worn on the force captured officers kicking a handcuffed alleged car thief. Two officers were suspended; three were placed on modified duty. Bellone has since included body cameras in the county’s police reform plan.

In a police reform plan approved by lawmakers Monday, Nassau County Executive Laura Curran also endorsed widespread body camera use for the first time.

‘A perfect teaching tool’

Fred Klein, a former chief prosecutor in the Nassau District Attorney’s Office, teaches at Hofstra Law School and has used the conflicts between the recording of Hayes’ arrest and the police accounts in seminars for aspiring prosecutors and criminal defense attorneys.

He called contradictions between a video that shows cops arresting a quiet, compliant man and written descriptions of the man resisting arrest and yelling abusive and obscene language “just a perfect teaching tool as far as police credibility is concerned.”

“I find it very difficult to imagine an innocent explanation for the discrepancy between the video and the police paperwork,” he said in a Newsday interview.

I don’t see how the police paperwork can be truthful given what’s shown on the video.

Fred Klein Former chief prosecutor in the Nassau District Attorney’s Office

Photo credit: Paul LaRocco

Klein prosecuted some of Long Island’s most notorious criminals of the 1990s, including serial killer Joel Rifkin and Amy Fisher, the teenager who shot her older lover’s wife. He noted that cops can be held criminally liable for making false official statements. The complaints filed by Arena and Ellison contain a standard disclaimer: “Any false statement made herein is punishable as a Class A misdemeanor.”

“It’s almost unjustifiable that there wasn’t probable cause to bring some charges here against the police,” Klein concluded of the officers, who were not subject to action by the Nassau District Attorney’s Office.

After the arrest, one of the officers told a prosecutor that Hayes had committed the alleged crimes before the recording began. Klein said, however, that specific indicators in the video all but ruled out that account.

“I don’t see how the police paperwork can be truthful given what’s shown on the video,” Klein said.

Had the officers been wearing body cameras, KIein said, the story that Hayes acted disorderly or resisted arrest earlier in the encounter would likely have been debunked.

“Since I believe the cellphone video itself establishes no criminality by Mr. Hayes earlier in the encounter, if the police had been wearing body cams, Mr. Hayes’ arrest would never have occurred, since their own equipment would not have shown any crime,” Klein said.

‘I got it on tape, too!’

When they arrested Hayes, Arena and Ellison were members of the Nassau Police Department’s Bureau of Special Operations, which includes the department’s SWAT team but also conducts plainclothes details targeting drugs, prostitution and other street crimes.

The officers were stopped at a red light in an unmarked car when they noticed Hayes standing in the barbershop’s back parking lot. They reported that they thought they saw him engage in a drug purchase by, they believed, giving money to a woman and putting a small object in his pocket. They also reported that the woman walked through the barber shop and left the scene as they pulled into the lot, got out of the car and approached Hayes.

Barbershop operator James Johnson recorded the video from the rear door of the business. He can be heard advising Hayes not to say anything, telling the cops Hayes hadn’t done anything to warrant arrest and asking, “They could lock you up for not giving a last name?” The officers never look in the direction of the camera.

To support the disorderly conduct charge, Arena wrote that Hayes’ outbursts included, “Go [expletive] yourself, you [expletive] white cracker cops,” and “I ain’t giving you [expletive] you can arrest my [N-word] ass.”

The video captured no such language.

Arena also alleged that Hayes’ yelling drew spectators in what records show were subfreezing temperatures, on snow-and-ice-covered blacktop.

“The crowd that gathered were a mix of elderly people and small children,” Arena stated. “The Officer’s (sic) asked the Defendant to stop his violent behavior numerous times. The Defendant refused to comply.”

A single person passes in the background of the video, appearing unaware of what’s going on as Arena and Ellison walk Hayes away.

In a complaint supporting a resisting arrest charge, Ellison described Hayes’ action and the scene in the same way and then added:

“The Officers attempted to place the defendant into custody. The Defendant started to swing his arms and upper body and pull his arms away from the Officers and refuse to place his hands behind his back. This action by the Defendant did attempt to prevent the Officers from effecting an authorized arrest of himself. The Officers told the Defendant numerous times to stop resisting arrest but the Defendant refused your Deponents commands. Finally the Officers were able to place the Defendant into custody.”

As captured in the video, Hayes follows the officers’ instructions without spoken or physical challenge.

Describing Hayes’ alleged threats after he was in custody, an assistant district attorney quoted him as telling Arena and Ellison, “I hate all white cops, I will Google your names and find out where you live,” and “I got guns and I’ll hunt you down and kill you [expletive].”

The alleged threats prompted the DA’s office to ask a judge to hold Hayes on $50,000 bail, even though he had been charged only with two noncriminal violations and one misdemeanor. The prosecutor also cited Hayes’ past criminal record, which included a then-12-year-old felony weapons possession conviction that had led to prison time. Records show no subsequent convictions.

The judge imposed $20,000 bail, still an amount more typically required after a felony arrest and more than Hayes could afford to post.

“What? I got a job; I didn’t even do anything,” Hayes told the judge, according to the transcript of his arraignment. “This is [expletive] crazy, man. I got it on tape, too.”

The court clerk set his next court appearance.

“Go get the tape,” Hayes said, before he was ushered back to jail.

No charges against officers

Rep. Kathleen Rice (D-Garden City), who was Nassau district attorney when Hayes was arrested, declined to comment about whether the DA’s office had considered filing charges against Arena and Ellison based on the contradictions between the video and their written complaints. A Rice spokesperson referred questions to the current district attorney, Madeline Singas.

Miriam Sholder, a Singas spokeswoman, confirmed in a statement that the office “did not pursue criminal cases against” Arena and Ellison “and absent exceptional circumstances, does not comment on investigations that are closed without charges.”

In 2015, Hayes sued the county, Nassau police and Arena and Ellison in U.S. District Court in Central Islip, alleging violations of his federal civil rights including false arrest, false imprisonment and malicious prosecution. In November 2020, the Nassau County Legislature unanimously approved paying Hayes $125,000 to settle the claims.

Hayes, who was 34 at the time of the arrest, has worked as a plumber and promoted his own line of clothing — U Better Behave — on social media. Facebook posts show that he participated in some of the local protests after the police killing of George Floyd last May in Minneapolis.

Hayes declined to be interviewed for this story, beyond his statement endorsing body cameras. Brett Klein, his lawyer in the suit against Nassau (who is not related to Hofstra’s Fred Klein), did not return requests for comment.

Petrillo, who served as Hayes’ criminal defense attorney following the 2014 arrest and brought the video to prosecutors’ attention, said in a written statement: “What Bobby would like to see is that everyone recognizes that God has no favorites. He created us all equally in His image and wants us to come together with love, united as one.”

On the day that Nassau prosecutors moved to dismiss the charges against Hayes, Petrillo had called them “false, fabricated, made up. None of it is real. It is all fantasy.”

Outcome of internal investigations unknown

A year and a half after they arrested Hayes, Arena and Ellison were among three plainclothes officers who pursued a man suspected of soliciting a sex worker outside an East Meadow motel. The man, Justin Daley, fled and crashed his car into another vehicle, killing its driver.

Daley pleaded guilty to manslaughter. Then-acting state Supreme Court Justice Patricia Harrington sentenced him to eight months in jail and probation, far less than the maximum of five to 15 years in prison. She wrote that the police officers had failed to activate the emergency lights on their unmarked vehicle when they first began following Daley.

Daley, a U.S. Marine combat veteran, and his attorney said he believed that he was fleeing an ambush robbery because the officers didn’t identify themselves.

“The judge by her sentence has clearly taken into account … the unfortunate fact that members of the Nassau County Police Department failed to follow police pursuit protocols,” Daley’s attorney, Brian Griffin, said after his client pleaded guilty in 2016.

To that point, Arena and Ellison had been the subject of a combined 29 civilian complaints and internal affairs investigations dating back to 2004, according to a document filed by Nassau County in Hayes’ lawsuit claiming confidentiality regarding details of the allegations.

Newsday last summer requested access to the officers’ records, along with the records of others involved in unrelated cases, under the state Freedom of Information Law. Despite the June 2020 repeal of 50-a, the New York State law that shielded police officer discipline, the Nassau Police Department turned over only heavily blacked out versions of those disciplinary histories.

After Commissioner Patrick Ryder denied an appeal for fuller disclosure, Newsday filed suit, alleging that the department had invoked “new and baseless reasons to refuse disclosure of virtually all substantive information regarding the investigation and discipline of Nassau County police officers.”

The court papers stated: “Newsday wants to inform and educate the public about the processes and standards of police discipline so that the public can judge whether law enforcement agencies operate in the best interest of police officers and the general public.”

The police department has not yet filed a response in the court action.

The four-page “Concise Officer History” report for Arena and 12-page report for Ellison are each almost completely blacked out. The only discernible facts are that Arena and Ellison in 2007 were each subject of founded complaints of unprofessional conduct and that Ellison was found to have broken unspecified departmental rules in 2009. None of those entries revealed discipline, and none appears to correspond to Hayes’ 2014 arrest.

Under a law that requires district attorneys to give defendants evidence that could potentially undercut the prosecution, the Nassau DA’s office has cited the Hayes case in letters to lawyers representing clients who faced trials at which Arena and Ellison were potential witnesses.

Prosecutors wrote that each officer “previously was involved in a case in which he arrested an individual for disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. There is a videotape of that arrest that does not show the individual resisting arrest.”

County payroll records show that Ellison, now a detective, earned about $198,000 in total pay in 2019. In December 2016, he was honored at the Nassau County Legislature as the Police Benevolent Association’s monthly “Top Cop” for leading the department’s “Toys for Tots” operation.

Arena, after roughly 30 years of service, left the department in November 2015, earning $209,217 in total pay that final year, the county records show. He was also paid $299,000 in accrued time during the 2016 payroll year, records show, and has a state pension of $149,476, according to SeeThroughNY, an Albany watchdog that promotes transparency in government spending.

An officer’s explanation

Neither Arena nor Ellison have publicly spoken about the arrest. John Wighaus, president of the Nassau Detectives Association, which now represents Ellison, declined to comment. Det. Lt. Richard LeBrun, a police department spokesman, declined requests for comment on behalf of Ellison or Ryder.

Arena provided his account to a prosecutor in February 2014, days after the video had surfaced and Hayes had been released from jail. Speaking to then-Deputy Bureau Chief Brendan Ahern, Arena said that the allegations in his and Ellison’s sworn statements occurred roughly 60 to 90 seconds before the video begins, according to a memo filed by Ahern and obtained by Newsday in a public records request.

In his telling, Ahern wrote, Arena said that “upon noticing the officers, Hayes immediately began cursing loudly at them with a range of expletives and comments about police officers.”

Arena said that when he asked Hayes to explain what they had just witnessed from their unmarked car, Hayes responded, “nothing happened.” When asked about the woman whom the officers said they saw exchange something with Hayes, he replied, “What girl?” and when asked his name, said “Go [expletive] yourself, you [expletive] white cracker cops.”

Arena told Ahern that he repeatedly tried to interject in the “tirade” to get Hayes’ name or identification, to no avail. He said Johnson — whom he didn’t identify by name — appeared at the back of his barbershop and rejected a call to go back inside, identifying himself as the owner.

During all of this, Arena said that he saw an elderly woman pushing a cart stop to see what was going on, followed by a woman and two small children, and “3-4 young black males.” Ahern’s memo doesn’t explain how long any of these people lingered and why they couldn’t be seen on the recorded portion of the incident.

About 45 seconds to a minute prior to the video starting, Arena recounted that he first told Hayes he was going to be arrested for disorderly conduct — something that appears to be contradicted by Ellison saying on the video, “I think this is a discon.”

Arena said he twice attempted to grab Hayes’ right arm with his left hand, but that Hayes swung it violently, causing Arena to “lose his balance and nearly slip on the ice,” Ahern wrote.

It was then, Arena recounted, he told Ellison “let’s slow down here.” Johnson “reappeared and stated to Hayes that he was going to get a camera.” Hayes told Johnson, “to go get it,” the report states.

Arena stated that he then removed a glass pipe sticking out of Hayes’ pocket, along with a small bag of marijuana. He told Ahern that he did not invoice the pipe because it appeared unused. He “was unsure what happened with the pipe,” but “recalls invoicing the marijuana,” Ahern wrote.

Arena told Ahern that the encounter captured on video started after he recovered those items. In the statement Hayes provided Newsday, he said he believed that the officers were unaware they were being recorded. Neither Arena nor Ellison appear to ever address the camera or look directly at it.

Picking apart officer’s defense

Via video conference, Fred Klein, the law professor and former prosecutor, broke down the recording as he does with his classes by examining whether it was plausible that the disorderly conduct and resisting arrest could have occurred in the 60 to 90 seconds before the video began, as Arena claimed.

Were that the case, Klein said, all of the spectators would have gathered and dispersed almost immediately while the incident continued.

Hayes would also have shifted almost instantly from threatening, profanity-laced shouting at the officers to speaking calmly.

“If he had used all this profanity that they had said, cursing and threatening them, would they have been treating him so courteously when they were arresting him?” Klein asked.

More important to Klein, Arena stands, with a relaxed posture, at more than arm’s length in front of Hayes as he speaks. He is not in a position indicating that he had just attempted to grab Hayes’ right arm with his left hand and had nearly slipped and fallen because Hayes had resisted.

Klein also noted that Hayes’ right hand held his cellphone, which police would have likely taken during a struggle. Additionally, Klein pointed out that the cops allowed Hayes to straddle his bicycle rather than remove it as a potential weapon within the reach of a combative suspect.

“Unless they arrested him, and then un-arrested him, and then the video began — which is preposterous — it couldn’t have occurred the way the police officers say,” Klein said.

I was innocent from the start.

Bobby Hayes in 2014

Photo credit: Howard Schnapp

In the video, Arena takes out his handcuffs only after Ellison, standing off to Hayes’ right side, states “I think this is a discon.” The comment suggests that the officers had decided at that moment that Hayes’ refusal to provide his name met the threshold of disorderly conduct — even though they said they had already been subject to his verbal tirade and already tried to arrest him, before pulling back.

When Arena states, on video, “You’re under arrest, you won’t tell us your name,” he makes no mention of resisting arrest, the only actual crime Hayes was charged with. Klein said that declining to provide a last name cannot be used as sole justification for an arrest.

Klein concluded that police “grabbed Mr. Hayes with no reasonable suspicion or probable cause. They demanded that he identify himself and explain himself, which the police have no authority to do. He refused to do that. And they decided to arrest him for disorderly conduct for not giving them the ID.”

“That is what’s on the video,” he said. “That’s what seems to me to be the reasonable explanation for what happened here. And then later on, they decided to blow it up and make it a resisting arrest as well.”

On the day in February 2014 that the criminal case against Hayes was dismissed, he stood outside the courtroom with his wife and said he was “just glad the truth came out.”

“I was innocent from the start,” he said.

CASE N0.1

CASE N0.1

CASE N0.3

CASE N0.3

CASE N0.4

CASE N0.4

CASE N0.2

CASE N0.2