Transparency denied: Why LI’s major police forces patrol without widely used body cameras

Long Island’s two county police departments are among a small minority of America’s largest local law-enforcement agencies that have spurned broad use of body-worn cameras, even as deadly encounters between officers and unarmed Black people increased calls for greater police transparency and accountability.

A Newsday survey of the nation’s 50 largest law-enforcement agencies found just three that had not equipped large numbers of officers with body cameras before 2020: The Nassau and Suffolk police departments and the Portland Police Bureau, in Oregon.

Deployment of body cameras as standard police equipment extends from the nation’s largest force, the 35,000-member New York Police Department, to smaller agencies, including Freeport’s 100-officer department. It has occurred as law-enforcement authorities and the public have come to rely on video recordings to document crimes and police conduct.

With profound consequences, civilian cellphones captured the asphyxiation deaths of Eric Garner on Staten Island in 2014 and George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020, while body cameras recorded the suffocation of Daniel Prude last year in Rochester.

Long Islanders protested after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

The Garner and Floyd videos generated protests that predominantly white police departments have used excessive force against unarmed Black people, with the Floyd recording reverberating nationwide, including on Long Island, where thousands of people participated in protests for weeks after his death.

Release of the Rochester body camera recordings, in response to a Freedom of Information Law request, prompted the resignations of the city’s police command. Body cameras also captured Floyd’s death, providing views at closer angles than the civilian cellphones, as well audio from police.

In February, Rochester police released body camera recordings of police handcuffing and placing a distressed 9-year-old girl in the back of a police car and pepper-spraying her. One officer was placed on suspension and two others were placed on leave.

Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone this month called for equipping large numbers of officers with cameras after one of the few devices worn on the force captured officers kicking a handcuffed alleged car thief. Two officers were suspended; three were placed on modified duty. On March 11, he released a police reform plan that endorsed deploying body cameras on officers who interact with the public.

A still image from a Suffolk County police officer’s body camera recording of officers allegedly kicking a suspect.

In a police reform plan issued in February, Nassau County Executive Laura Curran endorsed widespread body camera use.

Overwhelmingly, leaders of advocacy groups representing Long Island’s Black and Hispanic communities said in Newsday interviews that recording interactions between police and civilians would help clarify what took place in circumstances that are often disputed.

Voicing mistrust of Long Island’s forces, many of these leaders saw the cameras as a tool for promoting accountability and public confidence in law enforcement — but not as the sole answer to calls for broader policing reforms.

Last June, amid protests over the Floyd killing, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo directed local governments to study their policing with the goal of finding ways “to foster trust, fairness, and legitimacy, and to address any racial bias and disproportionate policing of communities of color.” Cuomo ordered municipalities and counties to submit reform plans no later than April 1, 2021, or risk losing state funding.

Curran and Bellone formed task forces, consisting of law enforcement officials, lawmakers, civil rights activists and religious leaders, to help craft the plans.

The process hasn’t always been smooth, especially in Nassau, where the activists, dissatisfied with their input into the process, resigned and released their own reform proposal shortly after Curran delivered hers. That document included her body camera proposal.

In November, Curran had reached a contract agreement with the Superior Officers Association, representing sergeants, lieutenants and captains, that included a $3,000 annual stipend for wearing cameras. Members of the much larger Nassau Police Benevolent Association then rejected a deal that included the same terms.

Union leaders, who later resumed contract talks with county officials, have said body cameras were not the reason the deal was turned down and would more often help vindicate officers accused of misconduct.

“Cops know body cameras are coming,” Nassau PBA president James McDermott said. “There is no reluctance to body cameras.”

Ryder projected cameras would cost Nassau police more than NYPD spends to equip over 10 times the officers.

Before Curran’s actions, Police Commissioner Patrick Ryder questioned whether body cameras would deliver enough benefits to justify their costs — projecting those to be higher than estimates gathered by Newsday.

“Almost every incident that I’ve ever had in this department, we’ve found other video that got us what we needed — commercial video, people’s cellphone video, doorbell Ring video, our own cops taking video,” Ryder said last June. “There is so many different ways now not to just dump $15 million.”

In August, he estimated the amount to be even greater.

“Originally when we did the cost out it was about $25 million a year, and that is most all storage,” Ryder said, referring to the expense of paying a vendor to store videos on computer servers.

In Suffolk, the police department equipped its 10-member drunken-driving enforcement team with body cameras in 2017 to provide juries with video evidence of inebriated driving. One of those cameras recorded the officers kicking the alleged car thief.

In a Newsday interview before that incident, Police Commissioner Geraldine Hart said the department’s research has verified that body camera costs can add up.

“It confirmed what we already knew,” Hart said. “It is a very high cost, with the storage of the information being the highest.”

In a perfect world, I think we are better off with body cameras than without.

Jackie Burbridge Long Island Black Alliance co-founder

With each county required to negotiate with politically muscular police unions, power, money and pro-and-con activism will guide whether the Island’s major forces ultimately equip their officers with body cameras. The debate will play out at a time when many leading figures in policing and advocates for policing reform express support for deploying the devices.

Said former NYPD Commissioner William J. Bratton: “I think it is a mistake to oppose them. In the vast majority of incidents, body camera footage is favorable to the officers.”

Said Long Island Black Alliance co-founder Jackie Burbridge, who helped lead Black Lives Matter marches after Floyd’s death: “In a perfect world, I think we are better off with body cameras than without.”

LI cops are behind the times on body cameras

To gauge the prevalence of body cameras, Newsday surveyed 50 law-enforcement agencies that ranged in size from the 800-member force in Minneapolis to the NYPD, an organization some 40 times larger.

Their officers patrolled large cities, such as Chicago and Los Angeles, as well as populous suburban counties, such as Montgomery County, Maryland, outside Baltimore, and Fairfax County, Virginia, outside Washington D.C.

Forty-one forces currently equip large numbers of officers with body cameras, with six more on track to do so this year. Most have deployed the devices for more than two years.

The departments in Fort Worth, Texas, and Pittsburgh began using them as far back as 2012. Houston and Milwaukee followed in 2013. Honolulu, Boston, Phoenix and El Paso adopted cameras from 2018 to this January.

The St. Louis police department equipped 100 of its 800 officers last year in a long-delayed rollout begun after civil unrest sparked by the 2014 fatal police shooting of an unarmed Black teenager, Michael Brown, in nearby Ferguson, Missouri.

The departments in Nashville, Tennessee; Kansas City, Missouri; Tampa, Florida; Fairfax County; and Prince George’s County, Maryland, began issuing the devices in late 2020 with plans to continue through 2021.

Joining the Nassau and Suffolk departments as one of the three major U.S. forces that has not adopted body cameras, the Portland Police Bureau serves a population of 2.1 million, roughly three-quarters of Long Island’s population as a whole. It shelved a body camera plan because of cost.

In contrast, the Baltimore Police Department — with 2,400 officers, similarly sized to the Nassau and Suffolk county departments — has equipped officers with cameras since 2016, the year after Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old Black man, died of injuries suffered while being transported in a police van. The death touched off protests and riots.

A U.S. Department of Justice study, published as Baltimore was embarking on its body camera program, found that, at that time, about 80% of the nation’s largest local police departments, defined as having 500 or more full-time sworn officers, used the devices.

Newsday discovers: The true cost of body cams

Cecilia Dowd explains Newsday’s investigative findings about failed efforts to equip Long Island’s largest police forces with body cameras — and what they would expect to spend using them.

Money.

Money to purchase cameras and equipment. Money to pay a tech company to store recordings in the digital cloud. Money for a staff to manage the body camera program. And money to boost the salaries of Long Island’s highly paid police forces as compensation for wearing the cameras.

Money has been the obstacle most frequently cited by police and public officials when asked why the Island’s forces have not been equipped with body cameras. That obstacle has grown larger with the fiscal stress brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

Potential price tags provided to Newsday by the two largest companies that sell body camera services, as well as expenditures by other police agencies, suggest body camera programs would cost Nassau and Suffolk millions of dollars a year — but likely less than Ryder’s $15-million to $25-million projections.

As one bench mark, the NYPD is slated to spend $10.4 million in the current fiscal year on body camera technology to equip about 24,000 officers — a number 10 times larger than the size of Nassau County’s force.

Executives with Axon Enterprise and Motorola Solutions, the two largest companies in the body camera business, say the price tag to equip Nassau and Suffolk police would depend on how many officers the departments want to outfit and the service plans they purchase.

“It really depends on what their needs are and what they want to accomplish,” said Jeff Childs, director of national sales of Axon Enterprise Inc., the dominant vendor in the body camera business.

Least expensive service plan:

$180 per officer- Video storage

- Video sharing

- GPS mapping

Most expensive service plan:

$2,748 per officer- Editing capability

- Live-streaming

- Civilian video uploads

- Tasers and holsters

- Camera activation when weapon drawn

Source: Axon Enterprise Inc.

Axon sells its cameras for from $499 to $699 each, depending on the model. Based on those figures, a department wanting to outfit 1,900 officers — the approximate number of cops covered by the Nassau PBA and the Nassau Superior Officers Association — would make an upfront investment of from $948,000 to $1.3 million.

Axon’s least-expensive data plan costs $180 annually per officer and includes video storage, upload and sharing, GPS mapping of recordings and scheduled deletion of files. A county choosing this option would spend $342,000 annually to outfit 1,900 officers.

Axon’s most expensive plan costs $2,748 per user annually. At that rate, Suffolk and Nassau would each spend $5.2 million a year to equip 1,900 officers.

The plan combines body cameras with Taser electric stunning devices. (Axon was known as Taser International until 2017.) Axon stores recordings on a Microsoft cloud; enables departments to redact sensitive information, such as interviews with confidential informants and interactions with minors; and allows departments both to store video provided by the public and to livestream recordings.

It also provides officers with Tasers, holsters and online training. Body cameras come equipped with sensors that prompt cameras to record whenever officers draw Tasers or other weapons.

Motorola Solutions’ list price is $828 annually per user, according to a company spokeswoman. The package includes equipment worn by officers and management of recordings. At that price tag, the cost would be about $1.6 million per year to equip 1,900 officers.

For an additional charge, the system enables departments to combine video and audio from car and body cameras, as well as 911 calls and GPS locations. It also allows police to view incidents from multiple perspectives, integrate video into evidence and use batteries that can swap from one camera to the next, eliminating a need to take cameras out of service for recharging.

Across the country, police departments spend widely different amounts to operate body camera programs.

The Seattle Police Department, which issued body cameras to 1,000 officers in 2016, allocates about $1.5 million a year for body cameras and data storage, according to Nick Zajchowski, the manager of the agency’s body camera program. That works out to $1,500 annually per officer.

The Miami-Dade police force spends about $1.2 million a year to equip about 1,600 officers with body cameras, or $750 annually per cop, according to spokesman Det. Argemis Colome.

Freeport Police department spends about $377 annually per officer.

Freeport police department Chief Michael Smith and village Mayor Robert Kennedy explain their body camera program to Newsday’s Cecilia Dowd and videographer Chris Ware on Oct. 19, 2020.

Freeport, the first police department in New York state to mandate the use of body cameras, equips 87 of its 100 officers with body cameras, Mayor Robert T. Kennedy said. The department, after an initial outlay of about $150,000, spends about $32,800 a year on replacement cameras and docking stations as well as licensing and storage, or about $377 annually per officer.

The Suffolk County Sheriff’s Office spent about $100,000 last summer to purchase 70 body cameras, and a plan that includes video storage and integrates the devices with car cameras and Tasers, for the deputies who patrol the county’s East End.

In addition to the costs of the technology, Long Island’s two counties would each pay millions of dollars annually to compensate officers equipped with body cameras.

“If I’m a stockbroker who takes on additional accounts, I receive the benefit of compensation from those accounts. If I am a teacher who takes on the responsibility of extracurricular sports activities, I receive compensation for that,” said Suffolk PBA president Noel DiGerolamo. “Why is it that people expect police officers to not receive the compensation commensurate with the extra responsibilities being asked?”

The cost of paying $3,000 annual body camera stipends, as was included in Nassau PBA’s rejected contract, would total $5.7 million to cover 1,900 officers.

Suffolk pays the handful of its DWI enforcement officers who wear body cameras an additional 2.5% in compensation. The average member of the Suffolk Police Benevolent Association earned $102,581 in base pay last year listed on W-2 forms, according to a Budget Review Office memo.

Those figures point toward paying an additional $2,564 annually to the average officer, with a total bill of $4.9 million to cover 1,900 officers.

Up to $11 Million annually.About 1 % of each police department’s budget.

Adding up all the projections using Axon’s most expensive pricing, the labor and technology costs for each county climb into the neighborhood of $10.1 million for Suffolk’s department and $10.9 million for the Nassau force — roughly 1.2% of Suffolk’s $838.9 million annual budget and 1% of the Nassau PD’s $890.7 million spending plan.

Seven years of attempts and failures

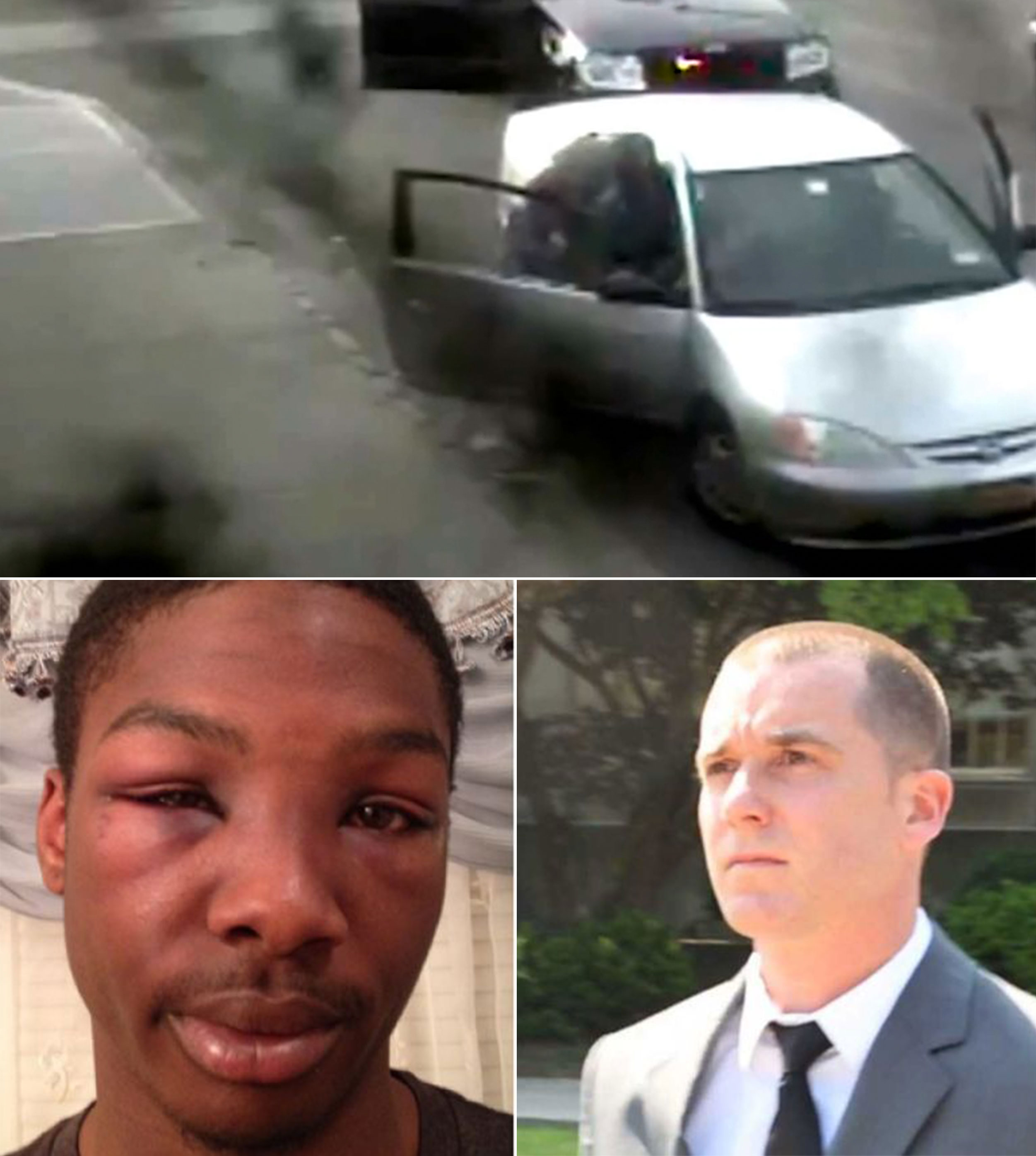

Kyle Howell was 20 years old when he suffered a broken nose, fractures near both eyes and nerve damage to his face in a struggle with Nassau police officers inside a car during a traffic stop in 2014. The officers charged Howell with assault, resisting arrest and possession of marijuana.

Howell’s family then discovered a store surveillance recording that contradicted elements of the police account. Reversing course, the Nassau District Attorney’s Office dismissed the case and instead indicted Nassau Police Officer Vincent LoGiudice for allegedly assaulting Howell, hitting him at least 18 times with his fist, knee and flashlight.

LoGiudice’s trial turned on whether he was justified to use that degree of force, based on a reasonable belief that his life was in danger. Howell testified that he lunged across the console of the car to grab a bag of marijuana from the glove box. The police officer testified that he believed Howell may have been reaching across the vehicle for a gun.

Clockwise from top: Security footage of Kyle Howell’s arrest; Officer Vincent LoGiudice walking out of court; Howell’s bruised face.

Delivering a not-guilty verdict at the close of LoGiudice’s nonjury trial, Acting Supreme Court Justice Patricia Harrington said Howell had testified that he knew “the police might think that he was posing a risk to them and they might think he was reaching for a weapon” when he grabbed for the marijuana.

Harrington also said that the video, recorded from outside the car, did not capture a full view of the events.

“It only depicts part of the actions of the defendant, which when viewed alone are disturbing,” Harrington said in court. “But the question in this case is what was happening in that motor vehicle — that cannot be seen from the perspective of that video camera.”

Responding to Howell’s case, Nassau County Legis. Siela Bynoe, a Westbury Democrat, filed legislation in 2014 that would have required the county police to equip cops with body cameras. Body cameras could have revealed what had taken place in Howell’s car, Bynoe said in a January interview.

“If a camera had been on the body of the officer, the interaction would have been captured and we would have had a clear look at what had occurred,” Bynoe said.

…we would have had a clear look at what had occurred.

Siela Bynoe Nassau County legislator

Without support from the legislature’s Republicans, who were in the majority, the bill never moved to the floor for a vote.

In 2015, then-County Executive Edward Mangano, a Republican, and then-Acting Police Commissioner Thomas Krumpter announced a pilot program to test the use of body cameras by outfitting 31 officers from the First, Third and Fifth precincts with the devices.

Police unions complained to the state Public Employment Relations Board that the department had violated labor law by failing to discuss body cameras with them.

“Whenever our members could be the subject of any type of discipline, whether it’s warranted or not, the union should have a say in how the body cameras are implemented,” then-Nassau PBA President James Carver said in December 2015.

The board directed the county and the police unions to engage in “impact bargaining,” which covers workplace changes that could affect employees’ work conditions. In this case, body cameras were not just new pieces of equipment, such as bulletproof vests, because recordings could be used to discipline officers.

The talks foundered, and Krumpter abandoned plans to equip Nassau police officers with body cameras.

“We reserved the right to review the video and we reserved the right to document misconduct in the video,” he recalled in an interview. “Anything that would encroach on that was a non-starter for the police department at that time.”

Krumpter is now chief of the 12-member Lloyd Harbor village police department, which is not equipped with body cameras. Still, he’s a proponent of the technology while being wary of its expense.

“The pilot would have showed whether the body cameras program was right for Nassau County. Did the benefits outweigh the significant costs? I would tend to believe so,” he said.

Suffolk Chief of Department Stuart Cameron said his department equipped its 10-member DWI enforcement team rather than the entire force based on a judgment that the costs would be too high when matched against the number of civilian complaints filed against officers.

“When you have a finite budget, you have to make decisions like that,” Cameron said, while also predicting that the need to recharge batteries and download videos “would definitely hurt response times” because Suffolk officers change shifts in the field rather than at a precinct roll call.

The impact of recording police in action

Brian Garcia and Michael Palazzo both wish that body cameras had long been standard equipment for Long Island’s police forces.

Palazzo is a former Nassau County cop. He says that a body camera could have saved his police career after a private security video contradicted details of his testimony about a 2017 drunken driving arrest — and prompted judges to reduce or dismiss charges in more than 60 of his arrests.

One of the body cameras used by Freeport police.

Regardless of the contradictions between his testimony and the video, Palazzo contends that the sights and sounds captured by a body camera would have shown that he was correct in making the arrest.

“I’m for body cameras, 100 percent,” Palazzo said.

Brian Garcia was pulled over on the Sunken Meadow Parkway by Suffolk County cops in 2016. He charges in a lawsuit that the officers had no grounds to stop him, that he was handcuffed for no reason and that the officers without cause pulled his pants down to his ankles on the side of the road to search him. In response, the county in court filings argued that the officers had probable cause to pull over and search Garcia.

“It would have made an impact” had the officers worn body cameras, Garcia said. “Maybe they wouldn’t have been able to fully do the traumatizing things they did.”

More than 24,000 NYPD police officers are equipped with body cameras, and those devices have been a plus for the New York City’s Civilian Complaint Review Board, according to a CCRB report released in February 2020.

Maybe they wouldn’t have been able to fully do the traumatizing things they did.

Brian Garcia

The report said body cameras have enabled officials to determine what occurred during an increased number of incidents that resulted in complaints.

Between May 2017 and June 2019, the CCRB fully investigated 318 complaints related to incidents captured by body cameras, according to the report. The panel determined the facts in 76% of the cases, compared with 39% of cases that lacked video evidence, the report stated.

“During the past two years alone, body-worn cameras have transformed civilian oversight of police in New York City, and it’s clear that this technology is here to stay,” the Rev. Fred Davie, the CCRB chairman, wrote in the report.

Brian Kelly, an assistant professor of criminal justice at Farmingdale State College, said his research shows that most cops and police unions believe body cameras protect cops from false allegations.

“If I’m conducting myself by the book, in a positive light, we want that as evidence,” said Kelly, a former Essex County, New Jersey, investigator and NJ Transit police officer. “Most of the time, what you see on a body camera is exactly what happened.”

Studies conducted in Rialto, California, a city of 100,000, and Las Vegas found correlations between the introduction of body cameras and reductions in complaints against police and the use of force by officers. Research in Washington, D.C., failed to detect similar trends.

Seth Stoughton, an associate professor of law at the University of South Carolina who has studied body cameras, said the Washington study should temper expectations about the technology.

“You have to be realistic about the possibilities of body cameras,” Stoughton said. “Body cameras are not always the best use of a department’s money.”

Police reform activists call for body cams

Tracey Edwards is the Long Island NAACP regional director, a member of a task force appointed by Bellone to recommend policing reforms — and was also among the community leaders who resigned from Curran’s task force over reform plan disagreements. She believes that Long Island officials should embrace equipping officers with body cameras.

We should use every tool we can…This is not an ‘us vs. them’ situation.

Tracey Edwards Long Island NAACP regional director

“We should use every tool we can to protect the community and officers, and body cameras are one of those tools,” Edwards said. “This is not an ‘us vs. them’ situation. We need to use technology to promote transparency, and body cameras need to be part of that discussion.”

Serena Liguori is director of New Hour for Women and Children, a nonprofit dedicated to helping incarcerated women and their children. As co-leader of the Long Island Social Justice Action Network, she helped organize Black Lives Matter protests after Floyd’s killing. She has a seat on Bellone’s task force.

They keep officers safe. They keep the public safe.

Serena Liguori Director of New Hour for Women and Children

“Body cameras will be part of the Long Island Social Justice Action Network agenda. They keep officers safe. They keep the public safe. I think it is a win-win,” said Liguori, whose network is a coalition of 34 community groups dedicated to statewide criminal justice reform.

Edwards and Liguori are among the leaders of nine Long Island civil rights and social justice organizations who expressed opinions about equipping Nassau and Suffolk police with body cameras in interviews with Newsday. Their groups have roots in both counties, as well as in the Black and Hispanic communities.

Overwhelmingly, they backed making cameras standard equipment on the county forces to increase transparency and public trust. Many said that they see the devices as only one part of a police reform agenda and that they are concerned about how the county departments would regulate their use.

“I do believe that what we have seen from national news, that sometimes the body cameras are indeed very helpful, to help with accountability,” said Elaine Gross, president of ERASE Racism, a regional civil rights organization based on Long Island. “We’ve seen that video in general has really changed the landscape.”

One activist opposed spending money on body cameras.

We believe we should be slashing the budget of the police.

Lucas Sanchez New York Communities for Change deputy director

Lucas Sanchez, deputy director of New York Communities for Change, said that police budgets should be cut in favor of spending money on services including health care, job training and education. He also said that a camera program would mask the need for new approaches to policing.

“They are a way for elected officials and police chiefs to say, ‘We did something,’ but nothing has fundamentally changed in their department,” said Sanchez, who said his organization has 20,000 members statewide, including 4,500 located mostly in the Island’s minority communities.

“We believe we should be slashing the budget of the police and use the money to give communities services that help working people,” Sanchez said.

Body cameras came to the fore as an issue for many of the activists following Floyd’s killing and Cuomo’s police reform order.

“We haven’t pushed for it as an advocacy issue,” said Theresa Sanders, president of the Long Island Urban League, who was appointed to police reform task forces formed both by Bellone and Curran. “But now with the current climate and everyone looking at how we can make our communities safer for everybody, that is a topic of discussion.”

E. Reginald Pope, president of the Nassau County chapter of the National Action Network, headed by the Rev. Al Sharpton, said Long Island agencies have resisted implementing body cameras because they have a history of secrecy about officer misconduct.

“Because of their practices and their behaviors, they don’t want to be recorded,” said Pope, who said his civil rights and social justice organization has about 150 members in Nassau and Suffolk.

While supporting the introduction of body cameras, Susan Gottehrer, president of the Nassau chapter of the New York Civil Liberties Union, said such a program would represent only a small step toward reform.

“It doesn’t address the systemic change that is necessary,” said Gottehrer, who called body cameras “low-hanging fruit” for officials eager to appear concerned about police reforms.

Nathalia Varela, associate counsel at LatinoJustice, called body cameras “one piece of a bigger puzzle” and said her organization calls for “appropriate training, policies and restrictions on data use” to prevent police from, for example, maintaining video files on selected individuals.

LatinoJustice is waging a class-action lawsuit alleging that the Suffolk County Police Department had engaged in a pattern of discrimination against Latinos.

Shanequa Levin is co-founder of the Long Island Black Alliance, which has more than 300 members and helped organize protests in Nassau and Suffolk after Floyd’s death.

“We know [body cameras] are not 100% perfect,” she said. “But they are a start to keeping police accountable.”

LI pols and police unions will decide

Freeport Police Officer Donnetta Cumberbatch describes the body camera she wears on patrol as a “safety net” that can dispel civilian complaints — typically a “my-word-against-yours kind of thing” — with documentary evidence.

It keeps us honest, productive, and it’s definitely a good thing.

Donnetta Cumberbatch Freeport police officer

“It keeps us honest, productive, and it’s definitely a good thing,” Cumberbatch said. “I don’t understand why [there] would be any hesitation having them.”

Kennedy, the village mayor, said the program’s $32,800-a-year cost is well worth the price.

“My officers don’t want to go out in the field without a body camera. They just feel it protects them. And it’s good for the residents,” said Kennedy, who also serves as police commissioner.

In 2019, body cameras captured a struggle in which Freeport officers punched, kicked and Tased 45-year-old Akbar Rogers as they arrested him on a harassment warrant after an alleged high-speed chase. A witness recorded the struggle on a cellphone.

After reviewing the body camera recordings, which have never been released, Nassau District Attorney Madeline Singas announced that the evidence did not support prosecuting the officers for using excessive force. She also dropped an assault charge lodged against Rogers.

He has filed a lawsuit that names as defendants eight Freeport police officers — two are Kennedy’s sons — Nassau County, the Village of Freeport and their police departments.

With a track record extending more than five years, Freeport’s force is the only local example of the costs and benefits of body cameras as Long Island elected officials and law enforcement leaders consider reforms. Whether Nassau follows Freeport’s example will play out amid conflict between its government and community leaders.

Civil rights lawyer Frederick Brewington, who had served as co-chairman of Curran’s police reform panel — before he and other advocates resigned over what they said was a lack of input into the county’s plan — said police departments should not pay officers to wear body cameras.

It’s like paying them to put on bulletproof vests. It is another part of their equipment.

Frederick Brewington Civil rights lawyer

“It’s like paying them to put on bulletproof vests,” he said. “It is another part of their equipment.”

Away from the negotiating table, they have wielded the power of campaign money.

“The PBAs in both counties are the most powerful public unions on Long Island,” said former Suffolk County Executive Patrick Halpin.

Kevan Abrahams, the Nassau legislature’s Democratic minority leader, expressed frustration with the PBA’s power.

“It’s crazy, but with something like this, where you’re trying to add a level of transparency and accountability, yes, unfortunately, they hold the cards because it needs to be in their collective bargaining agreement,” said Abrahams, who represents Freeport. “It frustrates me to the core.”

Photography: Chris Ware, Raychel Brightman, Howard Schnapp, Michael O’Keeffe

Reporters: Nicole Fuller and Michael O’Keeffe

Additional reporting:Cecilia Dowd, Paul LaRocco, Sandra Peddie, David Schwartz

Editors: Arthur Browne, Keith Herbert, Monica Quintanilla

Video producer and editor: Jeffrey Basinger

Video reporter: Cecilia Dowd

Videographers: Chris Ware, Raychel Brightman, Howard Schnapp, Cecilia Dowd, Randee Daddona, Thomas Ferrara, James Carbone

Digital design/UX: James Stewart, Anthony Carrozzo and Matthew Cassella

Project manager: Heather Doyle

Social media editor: Gabriella Vukelić

Print design: Seth Mates

QA: Pradeep Bhatee