Renewed rivals: Yankees vs. Rays

Jacob deGrom’s Cy Young competition

MLB Draft 2018: Be the GM

MLB DRAFT BE THE GM

Take control of the Yankees’ and Mets’ war rooms for the 2018 MLB Draft in this nine-round batting lineup simulator.

Select Your Team

Nick Fanti: Life in the minors

Chapter 1

'I knew he was special'

When Nick Fanti began playing baseball as a child, he didn't want to go anyway near the pitcher's mound. By his senior year at Hauppauge High School, the lefthander was attracting scouts for his pitching ability. Now he'll try to use that to get to the majors.

Lakewood BlueClaws/Mike Dill

Chapter 2

The Fanti famiglia

As the youngest of five and the only boy in the Fanti family, Nick Fanti said it was like he had five moms growing up. The tight-knit group made an effort to travel the 120 miles from Hauppauge to Lakewood, New Jersey, to see Fanti pitch as often as possible. Fanti also had support from his host family, the Hoffmans, who are BlueClaws season-ticket holders.

Lakewood BlueClaws/Mike Dill

Chapter 3

'Can you do it in three months?'

Lakewood pitching coach Brian Sweeney, who's also the coach for Team Italy, asked Nick Fanti, 20, if he would be able to pitch in the World Baseball Classic in three or four years. Then in December 2016, Sweeney asked Fanti if he could pitch in the 2017 WBC in March. Fanti threw a scoreless inning and struck out Mets utility man T.J. Rivera in his lone relief appearance against Puerto Rico.

WBC Inc.

Chapter 4

The no-hitter

Fanti made a name for himself on Long Island when he threw back-to-back no-hitters in high school. On May 6, he added his first professional combined no-hitter when he went 8 2/3 innings without giving up a hit against the Columbia Fireflies. His roommate, Trevor Bettencourt, closed out the game with a strikeout to preserve the no-no. Two months later, Fanti tossed a no-hitter of his own against the Charleston RiverDogs.

Lakewood BlueClaws/Mike Dill

Chapter 5

The last game

After the BlueClaws beat the Kannapolis Intimidators in the final game of the season, Fanti said goodbye to his teammates, fans and host family and headed back to Long Island for the offseason -- one step closer toward achieving his dream.

Lakewood BlueClaws / Mike Dill

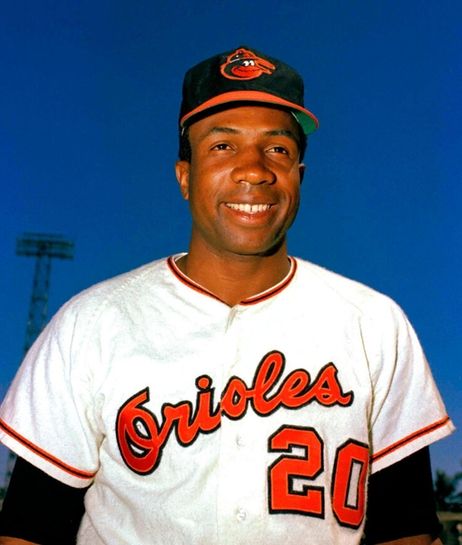

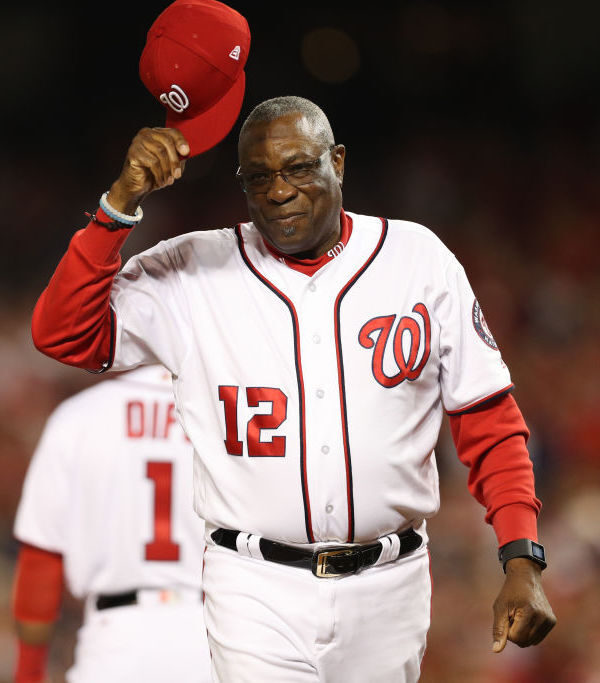

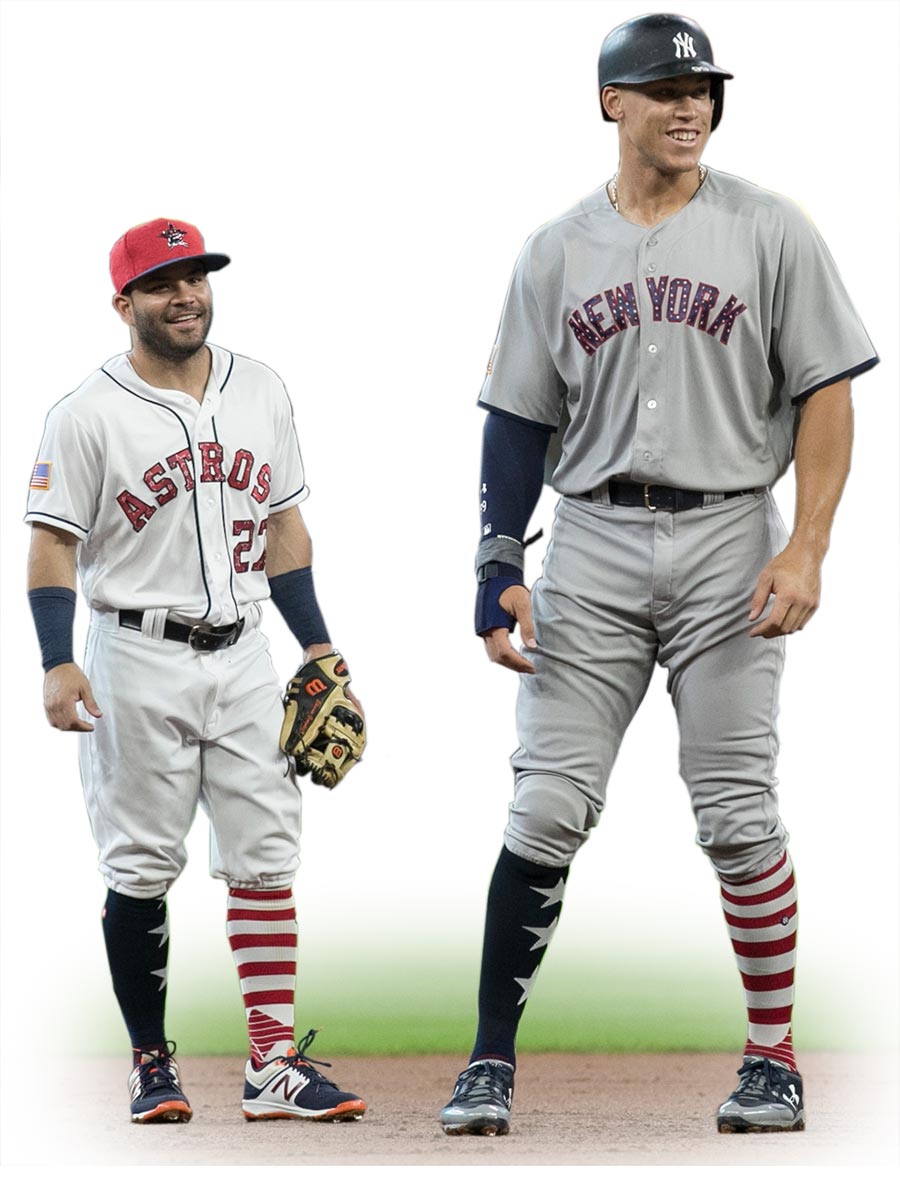

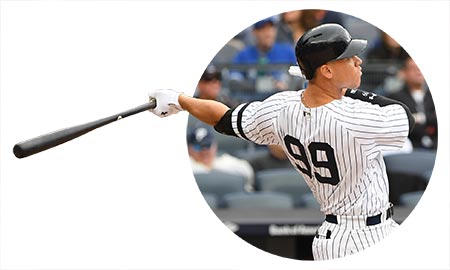

Tale of the tape: Aaron Judge vs. Jose Altuve

Yankees rightfielder Aaron Judge and Astros second baseman Jose Altuve are two of the leading candidates to win the American League MVP award, announced after the World Series.

But for the next week or so, they will be opponents in the ALCS. Here is the long and short of it when comparing Judge and Altuve.

Height

Jose Altuve is 5-foot-6

Aaron Judge is 6-foot-7

Jose Altuve stats

- Regular season

- .346 average

- 24 home runs

- 81 RBI

- 112 runs

- 204 hits

- 32 steals

- .410 OBP

- .547 slugging

- Postseason (through ALDS)

- .533, 3 HR, 6 RBI, 5 walks

Longest home run:

435 feet

May 15 at Marlins Park off Miami’s Dustin McGowan.

Average distance of home runs:

378.29 feet

Aaron Judge stats

- Regular season

- .284 average

- 52 home runs

- 114 RBI

- 128 runs

- 157 hits

- 9 steals

- .422 OBP

- .627 slugging

- Postseason (through ALDS)

- .125, 1 HR, 4 RBI, 5 walks, 16 strikeouts

Longest home run:

496 feet

June 11 at Yankee Stadium off Baltimore’s Logan Verrett.

— New York Yankees (@Yankees) June 11, 2017

Average distance of home runs:

415.48 feet

How the Yankees, the World Series and the presidency are connected

The Yankees are the most storied franchise in sports, having won 27 World Series titles. But despite having won a title an average of every four years during their history, a strange trend has emerged in the last six decades.

Since 1958, the Yankees have not won a World Series with a Republican president in the White House.

During that stretch, they have won at least one championship almost every time a Democrat was president (the lone exception being Lyndon Johnson).

Here’s a look at the strangely coincidental run the Yankees and the White House have had over the past 60 years:

Republican Donald Trump (2017-present)

0 championships so far. Last year, the Yankees lost a dramatic seven-game American League Championship Series to the eventual World Champions, the Houston Astros. This year, the Yankees beat the Oakland Athletics in the Wild Card round before losing to the Boston Red Sox in four games in the American League Division Series.

Democrat Barack Obama (2009-2017)

1 championship. The Yankees won the World Series in 2009. It was the only World Series the Yankees played in during Obama’s presidency.

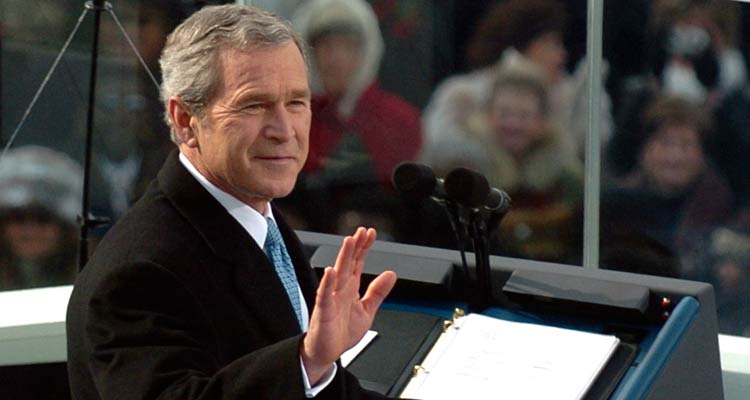

Republican George W. Bush (2001-09)

0 championships. The Yankees lost to the Arizona Diamondbacks in the 2001 World Series and to the Florida Marlins in 2003.

Democrat Bill Clinton (1993-2001)

4 championships. The Yankees beat the Atlanta Braves in the 1996 World Series, then the San Diego Padres in 1998, the Braves again in 1999 and the Mets in 2000.

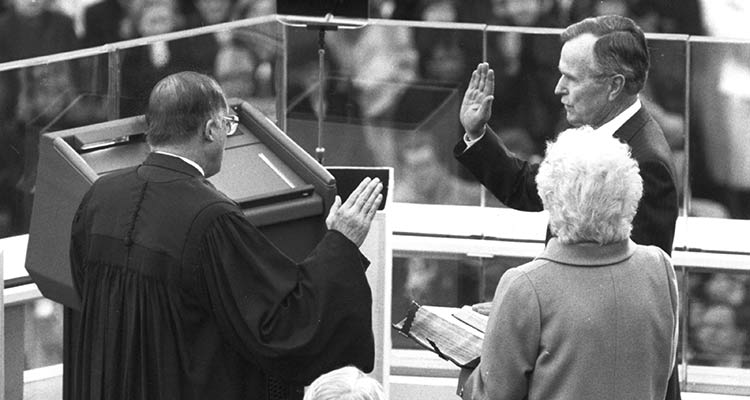

Republican George H.W. Bush (1989-1993)

0 championships. The Yankees did not reach the playoffs in any of these seasons.

Republican Ronald Reagan (1981-1989)

0 championships. The Yankees lost the 1981 World Series to the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Democrat Jimmy Carter (1977-1981)

2 championships. The Yankees won back-to-back World Series, beating the Dodgers in both 1977 and 1978.

Republican Gerald Ford (1974-1977)

0 championships. The Yankees lost the 1976 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds.

Republican Richard Nixon (1969-1974)

0 championships. The Yankees did not reach the World Series in any of these seasons.

Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969)

0 championships. The Yankees lost the World Series in 1963 to the Dodgers and in 1964 to the Cardinals.

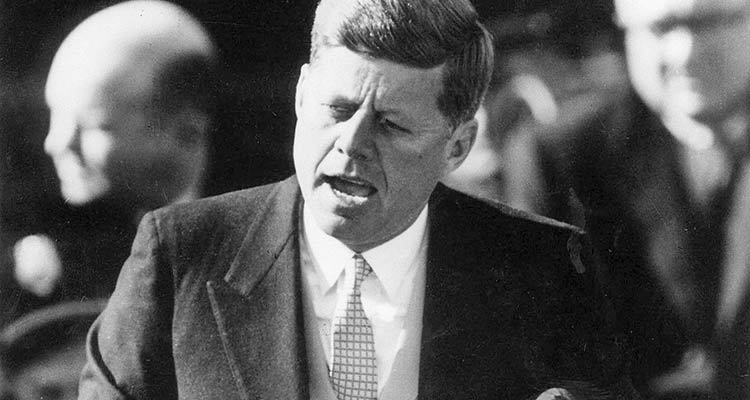

Democrat John F. Kennedy (1961-1963)

2 championships. The Yankees beat the Cincinnati Reds in the 1961 World Series and the San Francisco Giants in the 1962 World Series.

Republican Dwight Eisenhower (1953-1961)

3 championships. The Yanks won the World Series in 1953 to cap off a run of five straight titles. They won again in 1956 and 1958. The Yankees also lost three World Series in this span, 1955, 1957 and 1960.

The Yankees, the Mets and 3 MLB games in NYC today

The Yankees host the Royals at Yankee Stadium at 1:05 p.m., followed by the Mets with a doubleheader against the Braves at Citi Field starting at 4:10 p.m.

Game 1: Yankees vs. Royals — Game story | Boxscore

Game 2: Braves at Mets, Game 1, 4:10 p.m. | Boxscore

Tonight: Braves (Fried) at Mets (Lugo), Game 2, Shortly after Game 1 ends

Derek Jeter: The Captain’s most memorable moments for the Yankees

The defining moments of Derek Jeter

Derek Jeter is set to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Photo Credit: Getty Images / Al BelloThe First Hit

May 30, 1995

With shortstop Tony Fernandez injured, the Yankees called up highly touted prospect Derek Jeter for a cup of coffee.

The 20-year-old went hitless in five at-bats in his major league debut. In his second career game on May 30, Jeter earned his first major league hit, a single through the left side of the infield off Mariners pitcher Tim Belcher. After 13 games in “The Show,” Jeter was sent back down to Triple-A when Fernandez returned.

Opening Strong

April 2, 1996

Jeter was slated to begin the 1996 season as the Yankees’ starting shortstop by new manager Joe Torre despite initial hesitation from owner George Steinbrenner.

Batting ninth on Opening Day, Jeter smacked his first career home run off Cleveland’s Dennis Martinez in the fifth inning of a 7-1 Yankees victory. The dinger ended any doubt that Jeter was ready, setting the tone for his 1996 Rookie of the Year campaign.

The Maier Catch

Oct. 9, 1996

In Game 1 of the 1996 ALCS against the Baltimore Orioles, the Yankees trailed by one run in the bottom of the eighth with Jeter at the plate.

The shortstop swung at the first pitch from Armando Benitez, sending rightfielder Tony Tarasco back to the wall. As Tarasco reached up, soon-to-be folk hero Jeffrey Maier reached out, pulling the ball out of play and into the stands. Tarasco contested that 12-year-old Maier interfered, but rightfield umpire Richie Garcia ruled it a home run for Jeter. The Yankees won the game, the series, their first AL pennant since 1981 and the World Series, kickstarting a dynasty that produced four titles in five seasons.

All-Star MVP

July 11, 2000

Jeter lost in fan voting to Alex Rodriguez for AL starting shortstop ahead of the 2000 All-Star Game, but with Rodriguez unable to play Jeter took full advantage.

In the 71st midsummer classic, Jeter became the first Yankee to win the game’s MVP award after going 3-for-3 with a double and two RBIs. He picked up hits off Randy Johnson, Kevin Brown and Al Leiter, including a two-run single off Leiter in the fourth inning to give the AL the lead.

Subway Series

October 2000

In his fourth World Series, Jeter had his most outstanding performance.

The Yankees shortstop was key to the Pinstripes’ Subway Series victory over the Mets in 2000, especially with his performance in Game 4. Jeter went deep on the first pitch of the game off Mets starter Bobby Jones, later adding a triple. In the series-clinching Game 5 win, Jeter smacked another home run to even the score in the sixth inning. He was named series MVP, becoming the first player to win both All-Star and World Series MVPs in the same season.

The flip

Oct. 13, 2001

The Yankees were down 2-0 in the 2001 ALDS, but held to a 1-0 lead in the seventh inning.

With Jeremy Giambi on first, Terrence Long hit a Mike Mussina pitch to rightfield for a double. As Shane Spencer played the ball in right, Giambi rounded third. Spencer’s throw missed the cutoff man along the first-base line, but along came Jeter — from shortstop! — to save the day, gathering the ball and making a backhand flip to catcher Jorge Posada, who swiped Giambi for the final out of the inning. The Yankees won the series in five games.

Mr. November

Oct. 31-Nov. 1, 2001

After the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks forced the entire baseball calendar to be pushed back in 2001, Jeter and the Yankees were only up to Game 4 of the World Series against the Diamondbacks when the final day of October came around.

The game reached extra innings, and as Jeter stood at the plate, the clock struck midnight, marking the first World Series moment ever in the month of November. Moments later, Jeter smashed a fly ball to rightfield for a game-winning homer, tying the series at 2-2. Arizona won the series in seven games, but Jeter picked up a new moniker.

The Dive

July 1, 2004

As the Yankees-Red Sox rivalry reached its peak in 2004, the clubs battled into extra innings on July 1 at Yankee Stadium.

In the top of 12th with two outs and runners on second and third, Boston’s Trot Nixon hit a popup along the third base line. Jeter gave chase and made the catch along the line at full speed. Unable to stop, Jeter dove over the wall, tumbling over the photographers’ well and into the first row of seats. Jeter arose from the crowd with some marks and bruises to show for it and left the game the next inning, but his teammates picked him up, winning the game in the 13th inning.

Hit No. 2,722

Sept. 11, 2009

The Yankees’ all-time hit list is littered with legendary names – DiMaggio, Mantle, Ruth. For 72 years, Lou Gehrig sat atop the list with no one coming within sniffing distance of his 2,721-hit mark.

But in 2009, it became inevitable that Jeter would make the record his own. On Sept. 11, Jeter stepped to the plate in the third inning, smacking a ball down the line past a diving first baseman for career hit No. 2,722.

Hit No. 3,000

July 9, 2011

The Captain singled in his first at bat of the day, earning hit No. 2,999.

In his next at-bat, Jeter crushed a ball almost halfway up the Yankee Stadium bleachers in leftfield off Tampa Bay’s David Price, becoming just the second player ever to hit No. 3,000 with a home run after Wade Boggs. Jeter wasn’t done. He went 5-for-5 that day with two RBIs and a stolen base.

Walking off

Sept. 25, 2014

Derek Jeter reached on an error in the top of the seventh inning in his final game in the Bronx. That would have been his final at bat at the Stadium, but a ninth-inning Orioles rally tied the game and forced the Yankees to the plate once more with Jeter due up third.

Jose Pirela led off with a single and Antoan Richardson came in to pinch run. After Brett Gardner bunted Richardson over to second, Jeter came to the plate for his final at-bat in the Bronx. The Captain went with the first pitch he saw, driving a single to rightfield, scoring Richardson from second base and sending Yankee Stadium into a frenzy one last time with the walk-off win.

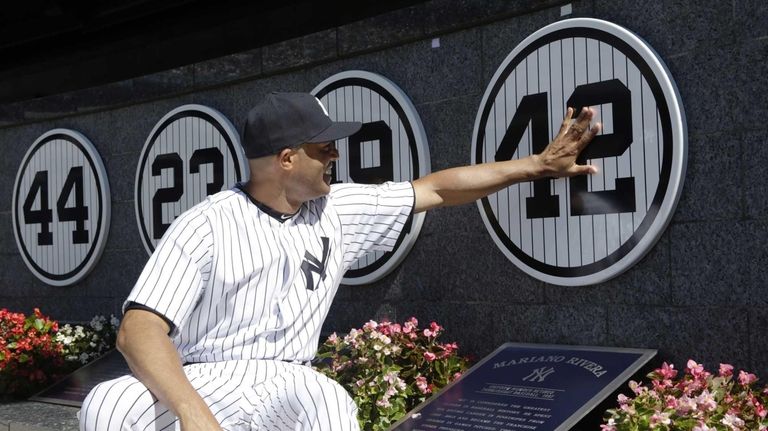

Numbers retired in Monument Park

Numbers retired in Monument Park

Derek Jeter joins these Yankees to have their number retired by the club.

Derek Jeter: Salute to the Captain

Derek Jeter: Salute to the Captain

Newsday’s 2014 documentary tells the story of what Jeter meant to Major League Baseball, its players and fans during his 20 seasons.

360 View: Mets Opening Day at Citi Field

360 View: Mets Opening Day at Citi Field

The scene at Citi Field before the Mets opened the 2017 season vs. Braves

Experience the Mets 2017 Opening Day with a 360-degree video of the sights and sounds inside and out of Citi Field. (Newsday / Jeffrey Basinger, Robert Cassidy)

Note: On mobile devices, the 360-degree video experience can be viewed only in the YouTube app.