Inside internal affairs Two mentally impaired men died in Suffolk police custody. Investigations protected the officers.

Police and prosecutors conducted flawed homicide probes in the deaths of Daniel McDonnell and Dainell Simmons, Newsday found.

The Suffolk County Police Department and District Attorney’s Office conducted flawed homicide investigations into the deaths of two mentally impaired men after struggles with police, avoiding full examinations of whether officers had committed crimes or violated department rules, a Newsday investigation has found.

Daniel McDonnell, a 40-year-old carpenter, suffered from bipolar disorder. He died inside the First Precinct building in West Babylon in 2011. Dainell Simmons, who was 29 and severely autistic, died two years later inside a Middle Island group home.

McDonnell and Simmons stopped breathing after officers provoked confrontations and then fought to restrain each man for transportation to hospitals. Officers pressed them to the floor in prone or partly prone positions that carried a high risk of suffocation.

Emergency medical technicians told homicide detectives that they found McDonnell lifeless on the precinct floor, facedown. Two saw his hands cuffed behind his back with a so-called spit hood over his head. Three police supervisors reported that officers had rolled McDonnell onto his side into a position that made it easier for him to breathe, as protocols required.

Handcuffed behind his back, Simmons, who was nonverbal, thrashed and screamed wordlessly for an estimated nine minutes under the weight of at least three officers at any one moment, until he suddenly fell limp and went silent, as if a light switch had been turned off, one officer testified in a civil lawsuit deposition.

Danielle McDonnell, widow of Daniel McDonnell, and Glynice Simmons, mother of Dainell Simmons, hold photos of the ones they lost. Credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

A decade later, emotional scarring remains fresh for the loved ones of McDonnell and Simmons. Although they don’t know each other and didn’t know what happened in each other’s case, McDonnell’s widow and Simmons’ mother share anger that no one was held personally accountable for the deaths.

“No one was punished. No one was demoted. No one was even suspended for a week. Nothing happened. No one was told to go and take a class on how to deal with mentally ill people. Nothing, nothing happened,” Danielle McDonnell said, adding, “Of course, it sticks with the whole family that there was never any real justice.”

Glynice Simmons recalled the protests that swept America after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020. A police officer had killed Floyd by pressing a knee on his neck for more than nine minutes while Floyd was handcuffed facedown on the street.

“With all the civil unrest, I think about how Dainell died, and that it’s still going on. Nothing has changed. Police are not being held accountable for what they are doing,” Glynice Simmons said.

Watch the video

The law empowers police to use force, including deadly force, in the line of duty. At the same time, the law requires police to use force properly. In New York, officers can be prosecuted if they are grossly negligent or reckless when they use force and kill someone.

Lawyers representing the McDonnell and Simmons families alleged in separate lawsuits that Suffolk police officers had wrongfully killed each man. The county paid $2.25 million in 2014 to settle the McDonnell case and $1.85 million in 2018 to end Simmons’ litigation.

To understand why Suffolk County spent more than $4 million to settle cases where no officers were charged with crimes or subjected to departmental discipline, Newsday’s Inside Internal Affairs project reviewed more than 5,000 pages of sworn testimony.

Questioned by lawyers for the McDonnell and Simmons families, police officers, supervisors and detectives described their roles in the events that led to the two deaths, as well as what happened in the homicide investigations that followed. Medical examiners and emergency medical personnel also testified.

Newsday presented key elements of the testimony to 19 former law enforcement officers, prosecutors and medical professionals who have expertise in topics including how police should engage with mentally impaired people, use force to subdue people and conduct homicide investigations. They have held positions ranging from New York Police Department lieutenant commander to sheriff of Ada County, Idaho, and vice chairman of the National Institute of Corrections, which establishes best practices for jails and prisons.

Long Island’s two major police departments are among the largest local law enforcement agencies in the United States. Protecting and serving, the Nassau and Suffolk county police departments are key to the quality of life on the Island – as well as the quality of justice. They have the dual missions of enforcing the law and of holding accountable those officers who engage in misconduct.

Each mission is essential.

Newsday today publishes the seventh and eighth in our series of case histories under the heading of Inside Internal Affairs. The stories are tied by a common thread: Cloaked in secrecy by law, the systems for policing the police in both counties imposed little or no penalties on officers in cases involving serious injuries or deaths.

These case histories document that Suffolk police and prosecutors shielded officers from full examinations of whether the officers committed crimes or violated department rules in the deaths of two mentally impaired men.

Daniel McDonnell had bipolar disorder. Dainell Simmons was severely autistic. Two years apart, they died after struggles with Suffolk officers.

Police arrested McDonnell on a misdemeanor charge. Officers described him as calm and cooperative. At the First Precinct, in violation of department regulations, a sergeant refused to give McDonnell the medications he needed or take him to the hospital. McDonnell suffered a psychiatric episode.

A lieutenant ordered McDonnell removed from a cell for transportation to a hospital. Thirteen officers participated in a struggle to subdue McDonnell, pressing him chest-down to the floor in a position that risked asphyxiation. He stopped breathing and died.

Simmons started wailing and running into walls in a group home after housemates had a snack that he did not. Police were called to take him to the hospital. Officers arrived. Simmons calmed and sat in a chair before officers discussed handcuffing him. He screamed, ran into another room and dove on the floor with his hands under his chest. Regulations called for officers to wait for a supervisor before acting.

Instead, three officers chased after Simmons and tried to cuff him, starting what turned out to be 18 minutes of struggling. In the last half of the struggle – a period estimated at nine minutes – the officers held Simmons to the floor, handcuffed behind his back. Like McDonnell, he was in a position that risked asphyxiation. He stopped breathing and died.

No officers were disciplined in either case. The McDonnell internal affairs investigation substantiated 10 charges of wrongdoing – after the Suffolk IA bureau failed to meet an 18-month deadline for filing the charges. The bureau closed the Simmons investigation without action.

Suffolk detectives and – in Simmons’ case – the Suffolk District Attorney’s Office conducted homicide investigations. Several criminal justice experts consulted by Newsday reporters David M. Schwartz and Paul LaRocco concluded that the investigations of both deaths had been designed to clear officers.

Newsday has long been committed to covering the Island’s police departments, from valor that is often taken for granted to faults that have been kept from view under a law that barred release of police disciplinary records.

In 2020, propelled by the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the New York legislature and former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo repealed the secrecy law, known as 50-a, and enacted provisions aimed at opening disciplinary files to public scrutiny.

Newsday then asked the Nassau and Suffolk departments to provide records ranging from information contained in databases that track citizen complaints to documents generated during internal investigations of selected high-profile cases. Newsday invoked the state’s Freedom of Information law as mandating release of the records.

The Nassau police department responded that the same statute still barred release of virtually all information. Suffolk’s department delayed responding to Newsday’s requests for documents and then asserted that the law required it to produce records only in cases where charges were substantiated against officers.

Hoping to establish that the new statute did, in fact, make police disciplinary broadly available to the public, Newsday filed court actions against both departments. A Nassau state Supreme Court justice last year upheld continued secrecy, as urged by Nassau’s department. Newsday is appealing. Its Suffolk lawsuit is pending.

Under the continuing confidentiality, reporters Sandra Peddie, LaRocco and Schwartz devoted more than 18 months to investigating the inner workings of the Nassau and Suffolk police department internal affairs bureaus.

Federal lawsuits waged by people who alleged police abuses proved to be a valuable starting point. These court actions required Nassau and Suffolk to produce documents rarely seen outside the two departments. In some of the suits, judges sealed the records; in others, the standard transparency of the courts made public thousands of pages drawn from the departments’ internal files.

The papers provided a guide toward confirming events and understanding why the counties had settled claims, sometimes for millions of dollars. Interviews with those who had been injured and loved ones of those who had been killed helped complete the case histories and provided an unprecedented look Inside Internal Affairs.

The former law enforcement officials reviewed how Suffolk police interacted with McDonnell or Simmons, how Suffolk homicide detectives investigated the deaths and how the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office responded. They then provided comments limited to specific areas of expertise, qualifying that they based judgments solely on the information provided by Newsday.

Many concluded that officers had unnecessarily and quickly used force against McDonnell and Simmons at times when the two men represented no threat to them, and that the officers had escalated the force after McDonnell and Simmons resisted.

“Both of these people were calm and non-combative until the police got involved,” said Fred Klein, a Hofstra University Law School professor and former chief of the Major Offenses Bureau of the Nassau County District Attorney’s Office. He cited McDonnell’s cooperative state before he was denied medication for his illness and Simmons sitting in a chair at an officer’s request before they discussed handcuffing him: “It’s probably what caused both of these men to die, eventually — that the police provoked it.”

Many also said the deaths demonstrated that police have been poorly trained to engage with people who are mentally ill or disabled. They pointed out that officers failed to speak calmly and patiently to McDonnell and Simmons as recommended by mental health professionals.

“Anytime you see the police involved [in psychiatric transports] there’s a risk that they’re going to go back into the ‘warrior’ policing or ‘command-and-control’ model that they use in responding more broadly to those labeled criminal threats,” said Jamelia Morgan, a Northwestern University Law School professor who has studied disability and policing. “It’s just not fitting.”

Morgan advocated for dispatching mental health professionals to many noncriminal calls involving mentally impaired people and urged a “more therapeutic model of policing” that would approach individuals with disabilities as people needing assistance.

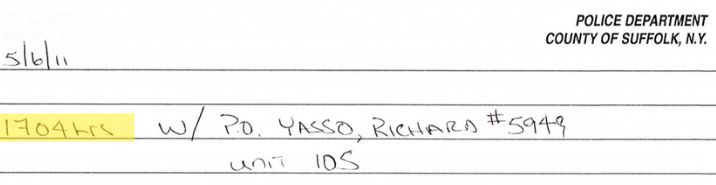

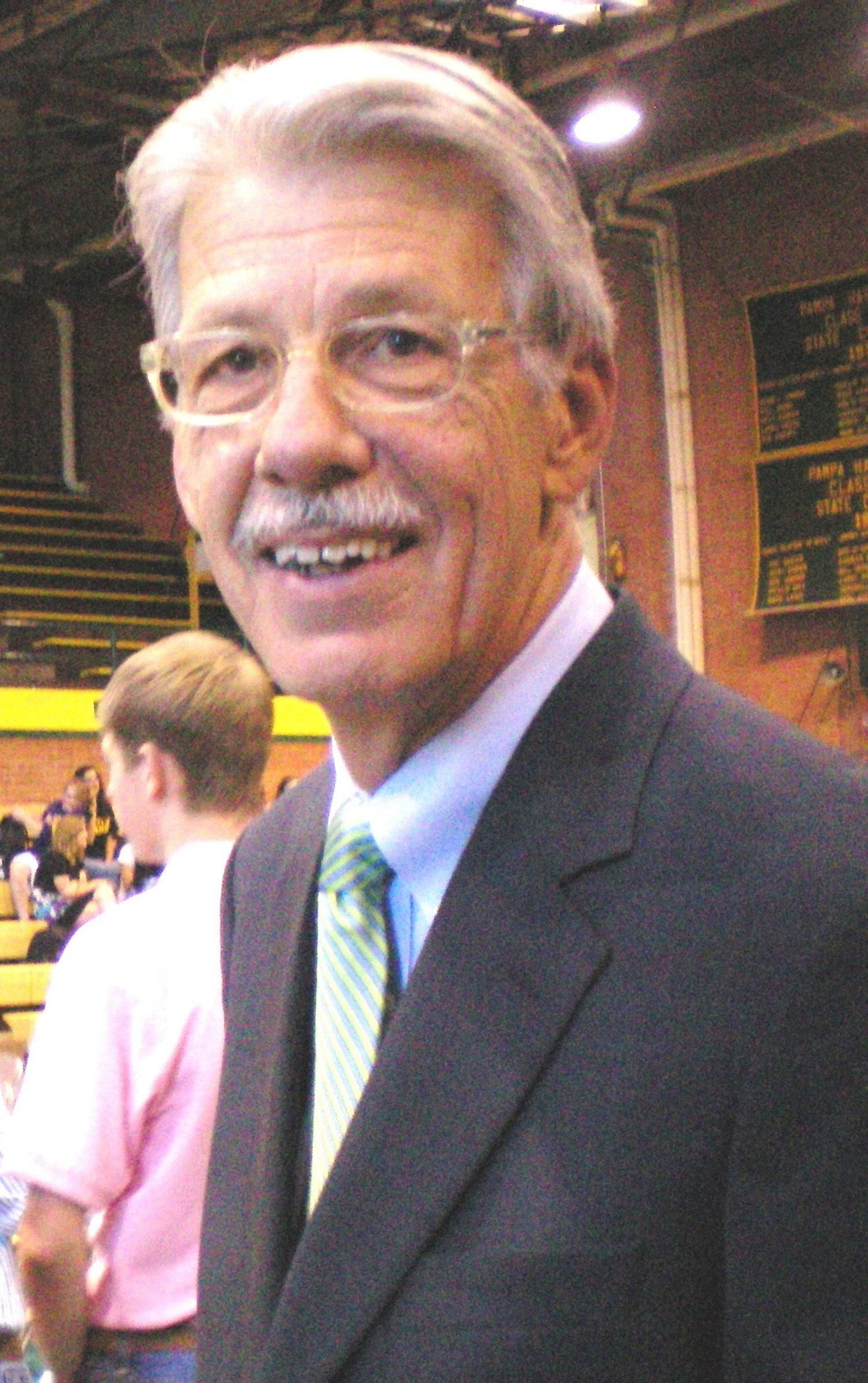

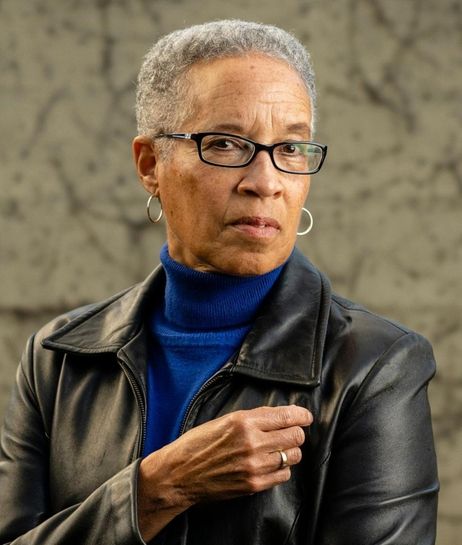

‘In both cases, it was clear that the intent was to protect the officers involved, and that, to me, subverts justice.’

Melba Pearson, director of prosecution projects for Florida International University’s Gordon Institute for Public Policy

Credit: Bryan Cereijo

The former prosecutors, police commanders and law enforcement officers who discussed the two deaths with Newsday described the investigations conducted by SCPD homicide detectives as “shoddy,” “sloppy,” “cursory” and “a sham.”

They cited, for example, that a homicide detective’s interviews with 10 of the officers who struggled with McDonnell lasted from two to five minutes each, according to the detective’s notes, and that the detective sergeant investigating Simmons’ death didn’t attempt to estimate how long officers laid on top of the man after he was handcuffed.

These experts noted that the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office, then led by Thomas Spota, failed to conduct a grand jury investigation into McDonnell’s death, and they saw evidence that a grand jury investigation into Simmons’ death was designed to avoid charging police.

“In both cases, it was clear that the intent was to protect the officers involved, and that, to me, subverts justice,” said Melba Pearson, who served for 16 years as a prosecutor in Miami-Dade County, Florida. She handled homicide investigations, including killings by police, and is now a Florida International University criminal justice professor and director of prosecution projects for its Gordon Institute for Public Policy.

“The big commonality is you’ve got the police investigating themselves, and I think both of these situations are prime examples about why that’s not a best practice,” Klein said.

Newsday attempted to reach members of the police department who participated in the events leading up to the deaths of McDonnell and Simmons, as well as to contact detectives — one has since died — and a prosecutor who conducted investigations. Other than the Simmons prosecutor, who cited grand jury secrecy laws in declining to comment on the majority of Newsday’s findings relevant to his role, calls and emails were not returned.

Additionally, Newsday explained its findings and the opinions of the experts in 28 letters sent to all the individuals by FedEx. The letters invited each individual to speak with Newsday about the information.

Newsday also sought comment about the findings through the presidents of the county’s three police unions — the Suffolk County Police Benevolent Association, Detectives Association and Superior Officers Association — and offered each the opportunity to speak on behalf of members, retirees or their unions at large.

They did not respond.

Police Commissioner Rodney Harrison, who took command of the SCPD at the start of the year, additionally did not respond to requests for comment.

Spokeswoman Dawn Schob said that in 2016 the department updated its protocols for removing a prisoner from a cell and that in 2019 it adopted a 40-hour, post-academy curriculum, called Crisis Intervention Training, that instructs officers in techniques they can use to prevent encounters with mentally impaired people from escalating into the use of force.

Spota didn’t respond to requests for comment made through his criminal defense attorney. He is serving a five-year federal prison sentence after his conviction on corruption charges.

State law now gives the New York Attorney General’s Office jurisdiction over investigating and prosecuting all police-involved deaths. Ray Tierney, the current Suffolk district attorney, said in a statement that the statute of limitations has expired on any potential charges against anyone involved in the McDonnell and Simmons cases. He declined to comment on the decisions of past administrations.

For nearly a half-century, police disciplinary files in New York were sealed by law. In 2020, after Floyd’s murder, state legislators and then-Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo repealed the law, known as “50-a,” that had imposed near-total secrecy on police disciplinary files.

The Nassau County Police Department has claimed continuing power to withhold almost all internal disciplinary records. The Suffolk County Police Department has released records only in cases where charges had been upheld against officers.

Newsday is pressing lawsuits against both departments with the goal of establishing that the public has a right to review how Long Island’s police forces police themselves. In November, an upstate appeals court upheld the release of Rochester and Syracuse police department disciplinary records in suits filed by the New York Civil Liberties Union.

Invoking the state Freedom of Information Law, Newsday last year sought the homicide and internal affairs records related to the McDonnell and Simmons deaths.

SCPD responded that it needed time to redact information from the McDonnell records and provided none of them. It denied access to the Simmons records, stating that an internal affairs investigation did not substantiate charges against any officer.

The McDonnell family provided copies of the police internal affairs report obtained in its lawsuit, as well as the Suffolk County medical examiner’s autopsy report. The district attorney’s office provided records of the McDonnell homicide investigation, including a Suffolk police detective’s notes of interviews with officers and emergency medical technicians.

The district attorney’s office denied a similar request for its Simmons files, saying they had been sealed following the grand jury presentation that resulted in no indictment being returned against the officers.

In December of last year, Newsday’s Inside Internal Affairs project began to publish case histories revealing that the internal affairs systems of the Nassau and Suffolk police departments had imposed little or no discipline on officers in cases involving serious injuries or deaths. The case histories have centered on records entered in evidence in lawsuits filed against the departments or provided by sources and family members who questioned how police investigated allegations of misconduct.

This story relates the seventh and eighth case histories. It also documents how Suffolk detectives and the district attorney’s office responded when they bore responsibility for determining whether police actions could warrant criminal charges.

New York’s Penal Law empowers prosecutors to charge police with criminally negligent homicide if the officers fail to recognize that their actions posed “a substantial and unjustifiable risk” of death and they “grossly deviated” from showing reasonable care.

Based on the information in Newsday’s case summary, three former prosecutors judged that a district attorney would lack the evidence necessary to prove that officers had been grossly negligent in subduing McDonnell. One saw the possibility that an investigation may have shown criminally gross negligence among the officers who subdued Simmons.

Bennett Capers, who served in the Manhattan U.S. Attorney’s Office and directs the Fordham University Center on Race, Law and Justice, said proving criminal negligence is difficult because police “just have so much leeway” to use force in self-defense or when restraining someone.

Klein saw the possibility that a prosecutor may have had grounds to file a lesser charge against a sergeant for refusing to provide McDonnell with medications he needed to remain stable.

The death of Daniel McDonnell

Daniel McDonnell grew up in Westbury. He met his future wife, Danielle, at W.T. Clarke High School. The couple bought a house in Lindenhurst. McDonnell worked as a contractor and carpenter. He and Danielle married and had a son in 2002.

Within the next few years, McDonnell was diagnosed as suffering from bipolar disorder. Medication helped McDonnell to live normally, his wife said. Without medication, he could have “episodes,” she said — periods of intense mood shifts, including depression and paranoia.

In early 2011, a neighbor secured an order of protection against McDonnell after a dispute. Returning from a court hearing on May 5, McDonnell and the neighbor drove down their street. The neighbor reported to the police that McDonnell had swerved at him.

Police brought McDonnell to the First Precinct in the early afternoon, charged with allegedly violating the order of protection, a misdemeanor. They described him as cooperative.

McDonnell’s mother brought two CVS pill bottles to the precinct. McDonnell had scratched his name off the labels but the prescribing doctor’s name, prescription number and pharmacy were visible, photos of the bottles show. Sgt. Frank Papillo testified in the lawsuit that he told McDonnell’s mother that the defaced labels prevented officers from dispensing the medications.

McDonnell’s mother testified that she told Papillo he could confirm the prescription by calling CVS. She quoted him as responding, “We don’t do that.”

Suffolk police regulations required officers to help prisoners obtain needed medications and to verify prescriptions, or to transport the prisoners to hospitals.

Papillo directed an officer to put the medications with the belongings that McDonnell had surrendered when he was taken into custody.

He failed to log the pill bottles or to file an emergency incident report, also as required, leaving no record that McDonnell’s medications were available in the precinct.

Depriving a prisoner of antipsychotic medications can increase the risk of hallucinations, disordered thinking and “bizarre behavior,” said Dr. Brent Gibson, former chief health officer of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, a not-for-profit organization that writes standards for prisons and jails.

“Cops are not doctors. If somebody is in custody, and they ask for medication and you don’t have that medication, call an ambulance and bring them to the hospital,” said Ralph Cilento, a former New York Police Department lieutenant commander of detectives who teaches police science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “After the hospital treats them, you can bring them back. Denying medication is inhumane.”

In sworn statements, two men also detained in the First Precinct described McDonnell as pleading for his medications with increasing desperation through the night.

Held on a criminal trespassing charge when McDonnell arrived, Shane Allen recalled that McDonnell requested medications unsuccessfully four times — as he was being walked to the cell, at dinner time, in the evening and in the early morning hours.

Between 3 and 4 a.m., Allen wrote, McDonnell loudly demanded the medications.

‘I woke to McDonnell screaming for his medication over and over.’

Detainee Shane Allen

“I woke to McDonnell screaming for his medication over and over. Nobody came to his cell. After 10-15 minutes, he began shaking the cell door and was making a lot of noise. He was still screaming, ‘I need my medication.'”

Police placed burglary suspect Paul Pizzitola in a cell at 2:30 a.m. He stated in an affidavit:

“About a half an hour after I was in the cell I heard a commotion outside. I could hear screaming, a male voice saying ‘I need my meds.’ ‘My mother brought my meds.’ I could hear another male voice yelling, ‘Shut up . . . before I shut you up,’ and ‘You don’t need your meds.’ There was noise and slamming bars off and on through the night.”

In contrast, every half-hour, including at the time McDonnell was reportedly frantic, officers described him on a prisoner activity log as “sitting” or “lying.”

Danielle McDonnell said that without his medication McDonnell could experience “like an anxiety attack times 100” that “was frustrating for him because he couldn’t deal with what was going on in his head.”

“So that’s what happened to him that night,” she said. “And then he starts to panic, and he paces, and then the heart rate goes up, and then he sweats, and then he starts doing, like, irrational things.”

A new shift started working at 7 a.m. on May 6. Lt. William Scrima took command. Testifying, he said he had no memory that the overnight supervisor had briefed him about McDonnell.

On a video monitor, a desk officer saw McDonnell use a cup to remove waste from the toilet, strip naked, rip his underwear and put it in the toilet. Scrima and Sgt. Henry Arnold went to the cell. The floor was flooded. McDonnell paced back and forth, saying “I need my meds,” Scrima testified.

Scrima asked McDonnell his name and what medication he wanted. McDonnell responded unintelligibly. Scrima checked precinct records. There was no mention of his medications: Papillo had failed to log them.

After observing McDonnell at the cell, Scrima watched via the video monitor. Suffolk police protocols call for “constant physical observation (one on one)” when “a prisoner’s physical or mental condition obviously warrants it.”

McDonnell took his clothes out of the toilet, put them on, took them off, and knelt in front of the toilet with his back to the monitor. Scrima testified that McDonnell appeared to be banging his head on the toilet and trying to tear his clothing into strips.

“I became concerned that he was gonna tie them up into a potential noose or something to hurt himself with,” Scrima said.

He requested the help of an Emergency Services Section team, a unit trained to handle situations requiring special tactics.

The nearest team was approximately 20 miles away. Scrima decided that McDonnell “should immediately be restrained for his own safety,” he wrote in a supplementary report, a document the police department uses to put an officer’s account in writing. He directed officers to subdue McDonnell for transportation to a hospital.

Experts in correction procedures said in Newsday interviews that trained officers can safely conduct cell extractions, including during psychotic episodes.

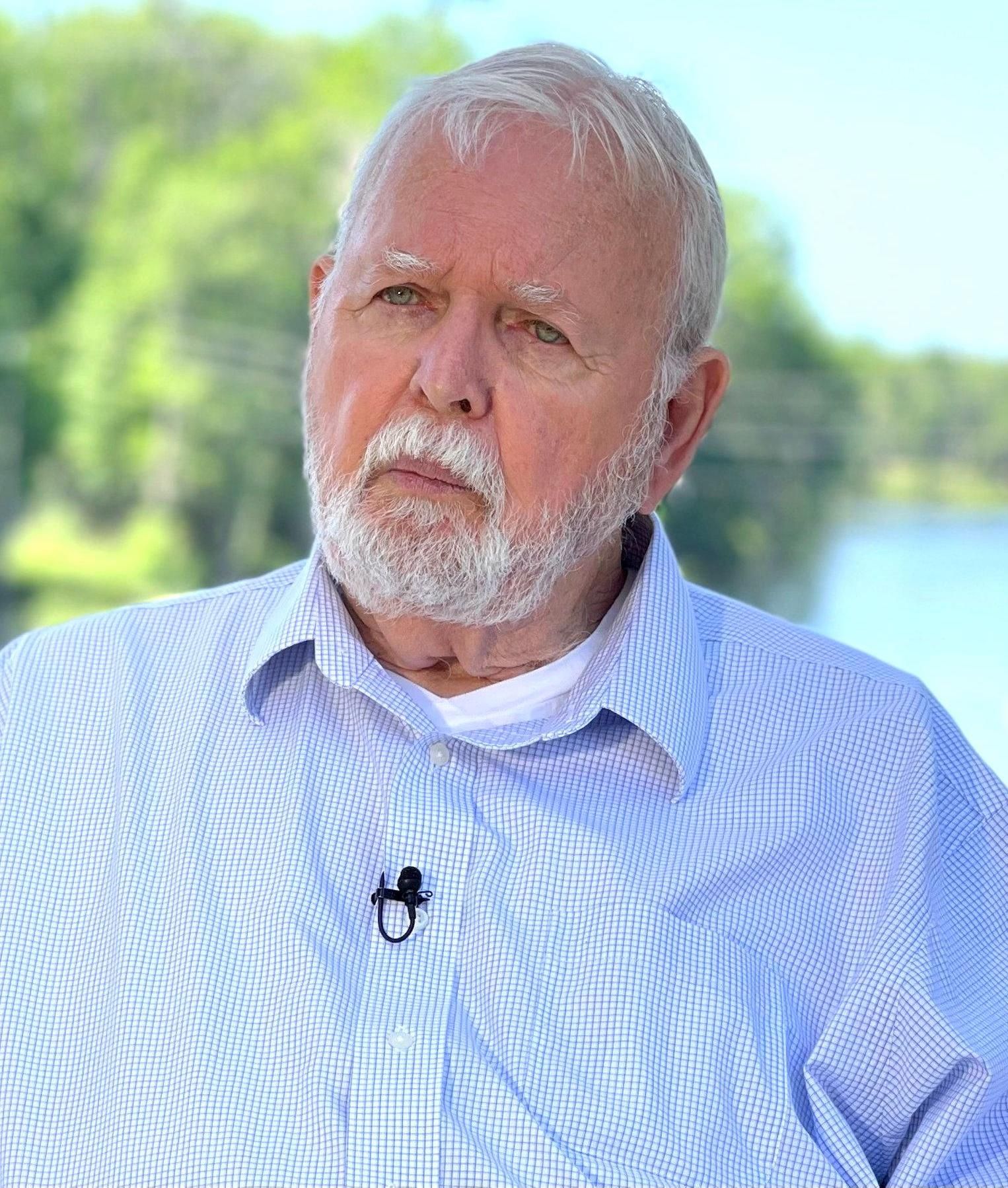

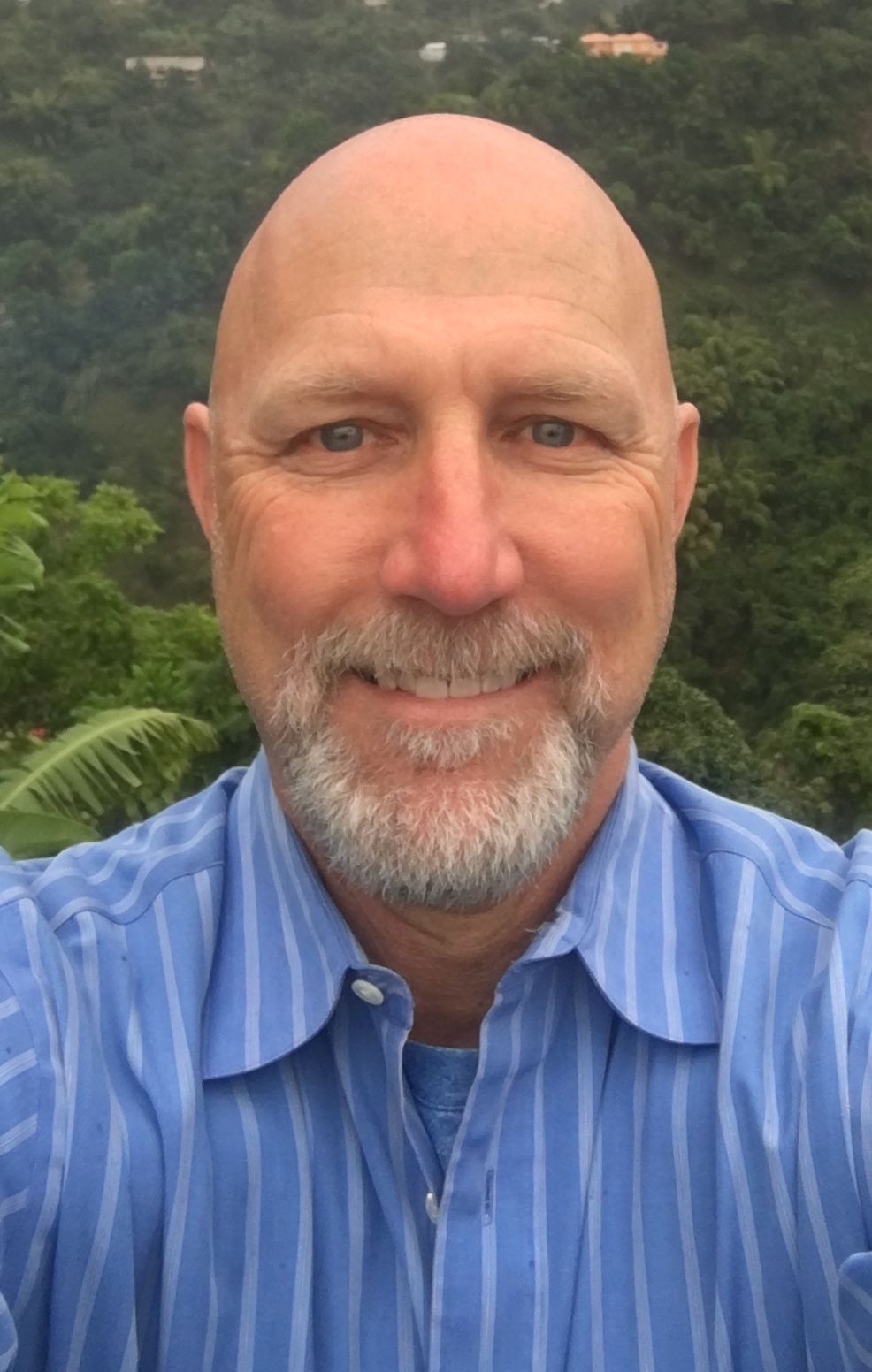

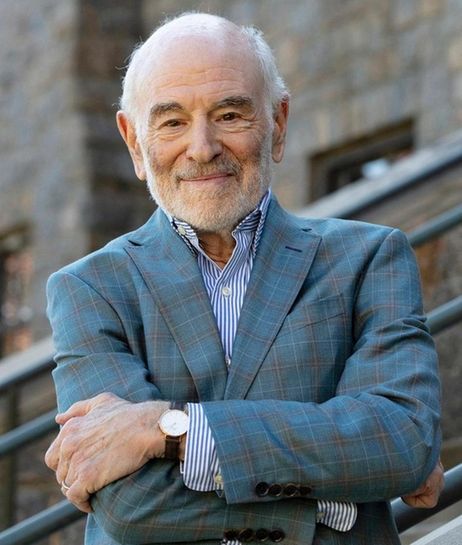

‘You should be able to bring a man out of the cell, sit him down and restrain him without putting a scratch on him, let alone killing him.’

Ron McAndrew, former warden of Florida State Prison

Credit: McAndrew Family

“You should be able to bring a man out of the cell, sit him down and restrain him without putting a scratch on him, let alone killing him,” said Ron McAndrew, a former warden of Florida State Prison and director of corrections in Orange County, Florida.

An extraction typically involves four or five officers, with team members assigned to take control of designated arms or legs, according to detention experts with experience in the tactic.

A supervisor should observe potentially quick-moving action to guide team members away from unintentionally using harmful force — for example, restricting a prisoner’s ability to breathe with a chokehold or by placing a prisoner chest-down on the floor, which experts said is known to be potentially lethal.

Scrima and the precinct’s officers testified that they had never been trained in how to extract a prisoner from a cell. He formulated a plan with two sergeants to immobilize McDonnell’s limbs with nylon restraints and handcuffs. They also decided to fire a Taser at McDonnell if he refused to comply.

Suffolk police policy stated that officers should use the electric shocking device only when “necessary to affect an arrest, for self-defense, or the defense of a third party.” The Justice Department had warned that a Taser could pose “a heightened risk for serious injury or death” if used against someone in a mental health crisis.

Steve J. Martin, who serves as the federal court monitor at New York City’s Rikers Island jails, said a Taser device should never be used on a mentally ill person who’s simply not following an order.

Sgt. Richard Bressingham prepared to deploy a Taser. He had not been trained to use one for six years, triple the time mandated by the department, according to an internal affairs investigation.

He gave 6-foot, 245-pound Officer Robert Bodenmiller a protective shell called a body shield that officers can use to push or pin prisoners. Bodenmiller had never been trained to use a body shield. He testified that no one discussed an extraction plan with him.

The two sergeants, Arnold and Bressingham, joined with Bodenmiller and Officers Andrew Young, Dane Flynn, Gregory Jungen, Richard Yasso, Adam Quinones and Patrick Ahearn.

Scrima handed Ahearn plastic “flex cuffs,” which resemble zip ties, and told him to restrain McDonnell’s legs, Ahearn testified. Quinones was given responsibility for trying to control McDonnell’s lower half, he testified.

After giving the go-ahead, Scrima stayed in an office. Martin described his failure to take direct charge as “kind of abandoning a post.”

“There are so many things that can go south. That’s why a detached observer, that’s not directly involved, is so critical,” Martin said.

McDonnell’s cell was 7 feet long by 4 feet, 9 inches wide. He knelt in front of the toilet with his back to the officers, according to testimony and written reports. Quinones described him as “very despondent.”

Bressingham said that he spoke to McDonnell in a “command voice.”

“I was calling him by his first name, ‘Daniel. Daniel,'” he testified. “Then I said, ‘Mr. McDonnell, we’re just trying to take you to the hospital. Turn around, Mr. McDonnell. Put your hands behind your back. We want to take you to the hospital.’ And I repeated it over and over again.”

Bodenmiller testified that Bressingham “was yelling some verbal commands to him, but we received absolutely no reply of any sort from Mr. McDonnell.”

Seth Stoughton, a University of South Carolina Law School professor and former police officer who has studied the use of force, said officers should try to quietly but firmly persuade a mentally ill prisoner to comply.

‘You don’t just shout verbal commands. You try to engage calmly, and you don’t aggress.’

Seth Stoughton, University of South Carolina Law School professor

Credit: Seth Stoughton

“For 30 years now, guidance in policing has been, you go slow,” Stoughton said. “You don’t just shout verbal commands. You try to engage calmly, and you don’t aggress. You try not to escalate or precipitate that use of force. Because someone in that crisis condition does not have the capacity to process and react the way that someone with all their normal faculties would react.”

Dr. Ravi Shah, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said yelling at someone who is agitated worsens agitation and aggression.

“They don’t get trained in how to handle mentally ill people,” Danielle McDonnell said.

Daniel McDonnell was 5-foot-10, weighed 236 pounds and was classified as obese. He stood up, still facing away from the door. Bressingham warned McDonnell that he would use the Taser if McDonnell didn’t put his hands behind his back.

A minute or two later, Bressingham fired the device, according to officers’ testimony. The prongs hit McDonnell in the back. They appeared to have no effect. Turning around, McDonnell asked, “Why’d you Taser me?” according to multiple accounts by officers.

Arnold fired a second Taser 32 seconds later, according to a Suffolk County Crime Laboratory analysis. McDonnell charged out of the cell, slipped backward on the wet floor, and slid into Bressingham, knocking the sergeant down.

McDonnell rolled onto his stomach and attempted to get to his knees.

Records indicate Arnold activated the Taser four additional times, in five-second bursts, between 7:30 and 7:33 a.m. Arnold testified he tried to restrain McDonnell’s legs with his left hand while he pulled the trigger with his right hand.

“Unknown if a shock was given because I noticed no change in his actions,” he wrote in his supplementary report.

Justice Department guidelines warned the repeated applications of electric shocking devices “may increase the risk of death or serious injury and should be avoided.”

McDonnell flailed, kicked, resisted shackling and fought to get up for an estimated 90 seconds to five minutes. Additional officers rushed to the cell block. A total of 13 participated in grappling to cuff McDonnell’s hands behind back and bind his legs with the flex cuffs.

“It’s very, very difficult to cuff somebody who doesn’t want to be cuffed,” Cilento said. “And so, the way we make up for that is in numbers. One cop, then two cops, then four cops, and we try to restrict movement.”

Bodenmiller testified that he placed the shield over McDonnell’s lower back, buttocks and upper thighs and laid on him “with my body weight” for an estimated two minutes. Officer Christopher Mills testified that he helped Bodenmiller hold McDonnell down with the shield.

‘You’re moving into the danger zone anything over a minute.’

Steve J. Martin, federal court monitor at New York City’s Rikers Island jails

Credit: Martin family

Martin said body shields are used in cells to initially restrain someone against a wall or “get them off their feet.” But pinning a prisoner down can restrict breathing, endangering life, he said.

“You’re moving into the danger zone anything over a minute,” Martin said.

Officer Riccardo Mascio pushed down on McDonnell’s right shoulder. He reported: “I placed my foot on Mr. McDonnell’s right shoulder and grabbed his right arm. He resisted me, so I applied force and twisted his arm back for cuffing.”

An autopsy photo showed bruising on McDonnell’s left shoulder, indicating contact with officers there, too.

“It has been well known and generally accepted in policing that officers absolutely should not keep a handcuffed subject in the prone (face down) position for an extended period of time, and they specially should not put weight on a prone individual’s back,” Stoughton wrote in an email, while also cautioning:

“The fact that he wasn’t in handcuffs yet is pretty important — putting someone facedown to facilitate handcuffing is pretty standard because it limits the person’s ability to resist, even if that takes a while.”

Quinones placed a foot on McDonnell’s thigh and held a wall for leverage pressing down.

Jungen reported that he handcuffed McDonnell’s right wrist, tried to pull McDonnell’s arm behind his back, and kicked McDonnell twice, once on his side and once on his back. He wrote that he administered the kicks after McDonnell tried to bite Jungen’s arm “while he violently swung his elbows and legs into me.”

Gary Raney, the former Idaho sheriff and member of the National Corrections Commission, said: “A kick is rarely an acceptable use of force, and only appropriate when there are no other options.” A kick near the spine can be a “near-deadly” use of force, he said.

Flynn noticed that McDonnell had started bleeding from his nose or mouth. He called for an ambulance and waited outside the precinct to rush paramedics into the building.

Scrima came out of the office.

“I could hear that — that they were struggling,” he testified.

Approaching the cells, Scrima saw blood and left to “make sure rescue was called.”

The officers secured McDonnell’s hands behind his back and restrained his legs with two sets of the flex cuffs, one around his ankles and another higher up on his legs. Ahearn continued to apply pressure to McDonnell’s legs.

Officer John McGlynn testified that he covered McDonnell’s head with a mesh like bag called a spit hood after McDonnell tried to bite an officer. Spit hoods are designed to prevent detainees from biting or spitting on officers.

Raney said that a spit hood can restrict breathing, worsening the danger of placing a handcuffed prisoner on his stomach. Stoughton said a soaking wet spit hood could make breathing difficult.

The standard practice among police departments is to roll handcuffed detainees onto their sides or to sit them up to avoid the risk of chest compression asphyxiation.

Suffolk police protocols stated that someone being restrained “shall preferably be on his/her side or prone with his/her face to the side and an open airway to prevent asphyxiation.”

Bodenmiller said they moved McDonnell to a vestibule area where the floor was dryer. “We just gently slid him along on his stomach and around the corner,” he testified.

McAndrew said that lifting the feet and shoulders of a prisoner who is face down “stresses the body to the point where you choke someone to death without realizing you’ve done it.”

McDonnell stopped breathing.

Three West Babylon Fire Department emergency medical technicians arrived. The EMTs — Daniel Foisset, Alyssa Coelho and Thomas Smyth — found a lifeless man, naked on the floor, restrained hand and foot with his head covered by a spit hood.

They told homicide detectives that McDonnell was face down, according to the detectives’ notes.

Coelho stated that “guy was naked; face down; rear cuffed plastic restraints around ankles.”

Smyth reported that he “saw person face down.”

Foisset described McDonnell as “lying on stomach cuffed behind back.”

EMT Daniel Foisset told police McDonnell was ‘lying on stomach cuffed behind back.’Detective interview notes

In a sworn statement, Foisset said that he checked McDonnell’s breathing and pulse, and found neither.

“I asked out loud how long he has been like this and was told about 3 minutes,” Foisset wrote.

Foisset removed the spit hood and asked an officer to remove McDonnell’s restraints. The EMTs moved him onto a stretcher and away from the wet area. Quinones reported that an EMT asked him to start CPR chest compressions, while Foisset ventilated McDonnell.

Police reports differed from the accounts of the EMTs.

Scrima and the two sergeants, Bressingham and Arnold, wrote that officers had rolled McDonnell onto his side.

Scrima wrote, for example: “After he was handcuffed, he lay on his side and continued to yell at the officers.”

None of the police officers described McDonnell’s position in their written reports. Testifying later, five officers stated McDonnell was placed on his side.

Officers also stated that the EMTs arrived within seconds after officers noticed McDonnell was not breathing.

McDonnell was taken to Good Samaritan Hospital in West Islip. He never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead that morning.

“It was absolutely absurd that 13 to 14 officers are on top of one man who is in a holding cell,” Danielle McDonnell said. “He is already in a holding cell, there was no need for that force whatsoever.”

Det. Ronald Leli led the investigation into whether officers were criminally responsible for McDonnell’s death. He interviewed them at the precinct late on the afternoon that McDonnell died.

Leli’s notes show that he completed interviews with 11 of the officers in a total of 50 minutes, finishing one in two minutes, according to his notes.

Leli recorded that a lawyer affiliated with the Suffolk County Police Benevolent Association attended most of the interviews. Police unions often provide legal representation.

“Every law enforcement officer, every corrections officer has a right to consult with an attorney before making statements under criminal investigation. And that includes making these statements,” Raney said.

In succession, Leli noted the time that each interview started. Often, he wrote only that the officers had confirmed the accuracy of their supplementary reports, and had given him copies.

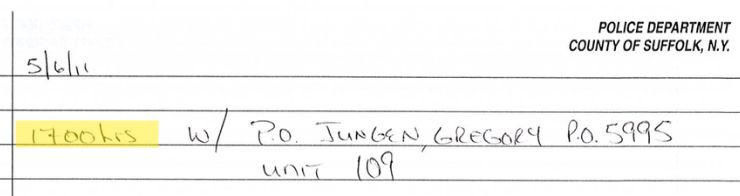

According to his notes, for example, Leli interviewed Jungen starting at 5 p.m. His notes read in full: “Supp reflects incident. Supp turned over.”

Four minutes later, according to the notes, Leli started to interview Yasso accompanied by a PBA attorney. The notes read: “Supp reflects incident. Supp turned over.”

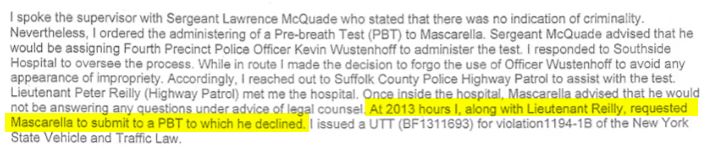

5 p.m.: Leli recorded interview start.Detective notes

5:04 p.m: Leli recorded next interview start.Detective notes

In lawsuit testimony, Officer Russ Capria described giving his supplementary report to Leli.

“He read it. He said, Is this accurate? Something to that effect. And we had a conversation for a few minutes,” Capria stated.

Sgt. Bressingham’s interview extended for half an hour, he estimated in testimony. He testified that detectives never asked about the force used to subdue McDonnell. He stated that he didn’t remember detectives asking about who used the body shield, who put the spit hood on McDonnell’s head, who used the Taser or how long it took to subdue him.

“So, to your memory, they didn’t break it down and say, ‘All right, which officer applied what amount of force?’ and broke it down piece-by-piece-by-piece to determine what kind of force was … employed against McDonnell, correct?” attorney Stephen Civardi, representing McDonnell’s family, asked.

“No,” Bressingham replied.

In his case report, Leli encapsulated the fatal struggle in three sentences.

Commenting on the notes showing that many of the detectives’ interviews lasted just minutes, Raney said:

“What I saw was indicative that this investigation was probably a sham. Simply if you compared it against a homicide investigation where the potential suspect was not a law enforcement officer, you would never see an interview in a criminal case that only lasted two minutes for somebody who was directly involved in the potential cause of death. That is just unheard of.”

He added in an email: “The criminal investigation violated generally accepted investigative practices and shows a bias to absolve the officers.”

Ayanna Sorett, who served for 15 years as an assistant Manhattan district attorney, called the investigation “very lacking and cursory.”

The investigation was ‘very lacking and cursory.’

Ayanna Sorett, former assistant Manhattan district attorney

Credit: Newsday/Jeffrey Basinger via Zoom

She said an assistant district attorney should have reviewed the officers’ written statements and the detectives’ notes and should then have interviewed the officers — likely with defense attorneys present.

“Most certainly, they would be interviewed, meaning spoken to extensively and questioned by the ADA who shows up to the precinct on call,” she said. “You have to make sure you have all of the evidence, so anything written, or anyone they’ve previously spoken with, who has written down an account of what they said, you want to be able to get all of those notes.”

Sorett added: “There certainly was enough that warranted a thorough and full investigation,” she said. “And I can definitely see bringing this before a grand jury after a thorough and full investigation” to determine potential criminal charges.

Cilento, the former NYPD lieutenant who spent more than half of his 28-year career in the detective bureau, said: “You can’t have a death investigation and have a one-paragraph statement by the cops that are involved,” adding that in a homicide investigation officers need to give formal statements. “And one paragraph, I’m sorry to say, in my experience, which is vast, to say the least, is not going to cut it.”

Spota, then the Suffolk district attorney, failed to conduct a grand jury investigation into McDonnell’s death, leaving as a last word Det. Leli’s finding that there had been no criminality.

“Why wouldn’t you let the members of the public [on a grand jury] determine if crimes are committed, make that decision as to whether the negligence rose to the level of criminality? Why does the homicide detective get to make that decision? To me, that’s just not the way to be running a homicide investigation,” Klein said.

Based on Newsday’s case summary, Pearson and Klein saw no grounds for filing charges against the officers who participated in the fatal struggle with McDonnell.

“It will be difficult with the limited investigation to determine who actually killed Mr. McDonnell,” Pearson said. “As such, who do you charge? Who caused his death?”

She also said that the lieutenant may legitimately have feared that McDonnell was on the verge of suicide, “which could make the decision to extract immediately reasonable.”

Capers, who directs the Fordham Center on Law, Race and Justice, said a prosecutor would likely have to prove that individual officers ignored training they had received.

‘Absent that kind of training, it just sounds like at most, they’re negligent.’

Bennett Capers, director of Fordham Center on Law, Race and Justice

Credit: Bennett Capers

“Absent that kind of training, it just sounds like at most, they’re negligent,” Capers said, adding: “This seems like the kind of thing where a civil suit does a lot of the work you wanted to do because a civil suit would force [Suffolk County] to actually do better training and that seems to be a large part of the problem here.”

Klein said, “I don’t see the struggle that they had as criminal” and saw it as an “indication of officers who were doing things that they may not have been well trained to do.”

Instead, Klein saw the possibility of holding the desk sergeant criminally responsible for refusing to provide the medications to McDonnell after they were brought to the precinct within an hour of him being lodged in his cell.

“There’s no reason why the desk sergeant couldn’t call CVS and say, ‘Did you prescribe this medication for this man?’ and provide it to him. I mean, the cops are supposed to protect and serve and not ignore and neglect,” Klein said. “To me, if there’s any criminality in that encounter, it was that. Maybe official misconduct, maybe reckless endangerment on the part of the sergeant.”

Cilento said an investigation may have substantiated grounds for dismissing a supervisor who ignored McDonnell’s pleas for medication.

“When you have this protracted time period, where this person is begging for help, begging for medication, I think that at least a senior officer there, the desk officer, the supervisor there, might bear some culpability, maybe not criminal prosecution,” he said. “I might support, after a sufficient investigation, department trial, that person losing their job.”

The Suffolk County Medical Examiner’s Office classified McDonnell’s death as a homicide and listed as a cause “sudden death following physical struggle and restraint in a person with bipolar disorder with excited delirium syndrome, hypertensive cardiovascular disease and obesity.”

Excited delirium syndrome has been cited by medical examiners and law enforcement authorities after sudden deaths of agitated individuals who are on drugs or are experiencing mental health episodes.

The American Medical Association, American Psychiatric Association and World Health Organization do not recognize excited delirium as a diagnosis. It is not in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a reference work used by clinicians and researchers. The American College of Emergency Physicians does recognize the diagnosis.

Lawrence Kobilinsky, professor emeritus of forensics at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, called excited delirium “a cause of death that has no real foundation in medicine.”

“It writes everything off and says it’s not the fault of police, it’s the fault of patients or the prisoner,” he said, adding, “It shields the police from further investigation into what caused a death.”

Two years after McDonnell died, the state Commission of Correction challenged the medical examiner’s excited delirium finding. The panel, which included forensic experts, pointed instead toward suffocation, writing that the medical examiner had “found abundant physical evidence of compression asphyxia.”

The commission concluded: “This was a preventable death had McDonnell been the subject of a properly supervised and controlled use of physical force and had he been afforded adequate emergency medical care.”

The death of Dainell Simmons

Dainell Simmons was diagnosed with autism and severe developmental delays at age 3. During his teens, his mother placed Simmons in a group home. He spoke mostly in one- or two-word sentences, needing prompts such as “What’s your name?”

For most of his 20s, Simmons lived in a Middle Island facility run by Maryhaven Center of Hope. He returned to his family in Uniondale on many weekends, lugging suitcases filled with CDs and video games.

Simmons, as a child with his mother, and as a teenager. Credit: Simmons family

On July 24, 2013, Simmons became agitated when housemates had funnel cake, a fried dough confection, and he did not. He wailed and ran into walls.

“Dainell could not communicate with his voice, so he would scream when frustrated,” Glynice Simmons said.

Counselors struggled to calm Simmons. They called the group home’s manager, who had left for the night. The manager, Miles Stewart, instructed the counselors to ask Suffolk police to take Simmons to Stony Brook Medicine’s Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program for an evaluation.

A 911 dispatcher put out the call as a resident “attacking” staff, though there was no evidence that Simmons had struck and injured anyone.

Seventh Precinct Officer Karen Grenia arrived first. Simmons was screaming and biting his own arm. Grenia asked Simmons to sit in a living room chair. He complied.

Officers George Oliva and Susan Cataldo arrived within four minutes.

Suffolk police policy directed officers, absent an immediate threat of harm, to summon a supervisor and the Emergency Service Section before attempting to take into custody any mentally impaired person who could be violent. It further directed them, if possible, to isolate the person and stay at least 20 feet away while waiting for support.

Grenia estimated that Cataldo was standing 5 feet from Simmons when she told a counselor that the officers would have to handcuff Simmons. Simmons bolted, yelling, “No police! No police!”

Cataldo called it “extremely loud” — a 10 on a scale of 1 to 10.

“He was poked and probed and put in machines, so he did not like doctors at all,” Glynice Simmons said of her son. “I’m sure that made the situation worse when they said they were going to take him to the hospital.”

The officers immediately chased him. Dainell Simmons dove onto the kitchen floor, screaming, with his hands under his chest.

‘I would have isolated and contained him. Autistic people will calm down if you just leave them. They need to self soothe.’

Ralph Cilento, former NYPD lieutenant commander of detectives

Credit: Newsday/Chris Ware

“I would not have taken the struggle to him,” said Cilento, the former NYPD lieutenant. “I would have isolated and contained him. Autistic people will calm down if you just leave them. They need to self soothe.”

Instead, Grenia, Oliva and Cataldo attempted to pull Simmons’ hands from under his chest, starting the first of two nine-minute struggles to handcuff him.

Grenia acknowledged in her lawsuit testimony that Simmons, at that point, posed no immediate threat and that she and the other officers had chased after him as “almost an instinct.”

Asked why they tried to handcuff Simmons, Cataldo said that officers worried he might try to go out a back door or into a room off the kitchen where group home residents and staff members had been placed.

“We were telling him put his hands behind his back, we didn’t want to hurt him, we’re going to take him to talk to a doctor,” Cataldo testified. “The whole time he was screaming.”

Simmons was 5-foot-6 and weighed 244 pounds. He bucked the officers off his body. They called for backup.

Stoughton, the University of South Carolina Law School professor who has studied the use of force, repeated that since the 1980s law enforcement protocols have directed officers to calm interactions with someone in a mental crisis when possible.

“In essence, the best approach is keeping the intensity level as low as possible and going as slow as the situation permits,” Stoughton said.

Grenia, Oliva and Cataldo dragged Simmons about 5 feet from a refrigerator they were afraid could fall over. He was still face down, but now flailed his arms, kicked his legs and tried to bite, officers testified.

Cataldo attempted to subdue Simmons by shocking him with a Taser applied directly to his lower back. The device had no effect. She fired the Taser’s electric prongs at Simmons, again with no apparent effect. A third attempt to shock Simmons, this time by Grenia, also failed.

“At one point we were all on top of him and he was throwing us off,” Cataldo testified.

The officers placed a second call for backup. Simmons got to his feet for a few moments and “in that process we all fell to the ground together,” Oliva testified.

On the floor again, the officers succeeded in handcuffing Simmons in front of his stomach. But he “arched his back and pushed us away with his body and got to his feet,” Oliva testified.

He said he believed that Simmons had never actually struck any of the officers.

But hearing the commotion over the radio, a police dispatcher broadcast a 10-1, an urgent call that indicates officers might be in danger.

Simmons “ran straight towards the front of the house,” Grenia testified.

Oliva said he feared that Simmons would run through the front door, which was open, and into the street. He fired Taser prongs into Simmons’ back. Simmons fell to his knees. From about 5 inches away, Cataldo sprayed pepper spray, known familiarly as Mace, into Simmons’ face. Simmons raised his hands. The officers shifted the handcuffs to behind his back.

Face down in the home’s foyer, Simmons kicked his legs, thrashed his body, and wordlessly screamed. Oliva radioed that the situation was under control, records show.

Suffolk police policy stated that people being restrained for transport should be upright, but if they must be lying down, “shall preferably be on his/her side or prone with his/her face to the side and an open airway to prevent asphyxiation.”

The policy also stated: “A prisoner in this position requires close and continuous monitoring…”

Edward Bracht, a Suffolk County officer who instructed recruits on the use of force, testified that generally officers should get people off their chests or stomachs as soon as possible.

“It’s understood that when the person is controlled and your safety is no longer an issue, to immediately roll them over to change their airway, not that there is a time limit on [it],” he said.

Cilento recalled that he “put an immense amount of pressure” on some detainees while making arrests, “but the minute you were rear cuffed … I would sit you up.”

Radio transmissions and lawsuit testimony indicate that the second of the two struggles again extended for nine minutes. Officers pressed Simmons against the floor in an apparent attempt to stop him from bucking, flailing and kicking his legs.

Oliva, who had less than three years on the police force at the time, placed a knee on one of Simmons’ shoulders and held Simmons’ head against the floor with a hand. Cataldo, a 10-year veteran in 2013, used her body weight to hold down Simmons’ torso. Grenia worked to control Simmons’ legs and feet until other officers relieved her.

Asked why they didn’t “back off and wait” for the emergency services unit, Grenia, then also a 10-year veteran, testified: “I don’t have an answer for you. I never have done that.”

The officers testified that they believed they were not harming Simmons’ ability to breathe because he maintained his screaming.

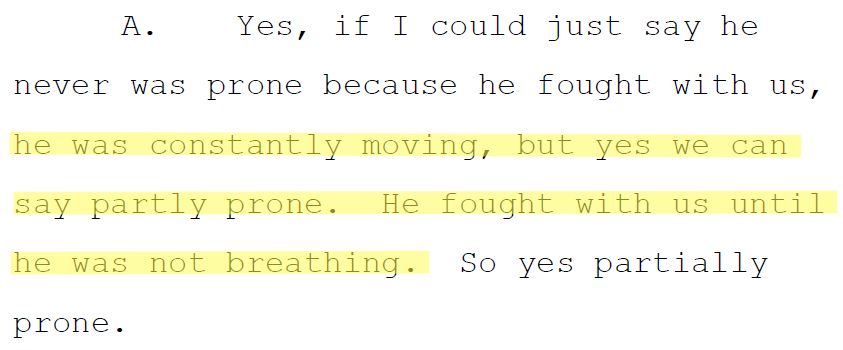

Cataldo described Simmons as positioned on his side when she pressed against his back. Oliva and Grenia stated, however, that Simmons was at least partly prone throughout the final part of the struggle.

“He was constantly moving, but yes we can say partly prone,” Grenia testified. “He fought with us until he was not breathing.”

‘He was constantly moving, but yes we can say partly prone. He fought with us until he was not breathing.’Testimony of Officer Karen Grenia

Stoughton said, “They especially should not put weight on a prone individual’s back. That’s even more true with obese individuals because of the increased potential that their gut will push up into the diaphragm, making it even more difficult for them to breathe while prone.”

Backup arrived, including then-Sgt. Frank Leotta. He radioed, about two minutes into the final restraint, that the situation was controlled. He requested both an ambulance and gurney to take Simmons to the hospital and flex cuffs to secure his legs.

Leotta testified that he believed Simmons was “contained in a safe position … because he was on his side on the floor screaming.”

“What I observed while I was there, there was nothing done wrong,” he said, describing the officers’ actions as “perfect.”

Stewart, the group home manager, returned to the scene.

“Dainell was still alive. I was trying to get to him because I know how to calm him. But [the police] did not accept that from me,” Stewart said in a Newsday interview. “I didn’t understand why so many people were on top of him, and he’s face down.”

Grenia reached exhaustion. James Poltorak, then a Seventh Precinct officer who had arrived in the urgent call for backup, testified that Simmons bucked and screamed in a position that likely at least partially compressed his chest.

Asked whether he believed that bucking had actually been Simmons “trying to get some air into his airway,” Poltorak answered: “At the time I believed it was him fighting and struggling.”

The flex cuffs took five minutes to arrive after Leotta’s call.

The four backup officers, including Poltorak, who restrained Simmons’ legs said it took approximately another two to three minutes to secure them in the cuffs.

Another officer, Kevin Wustenhoff, lifted one of Simmons’ legs off the floor to cinch it in the zip-tie-like cuffs. Within a minute, Simmons went limp and fell quiet. He had stopped breathing.

“Like a light switch,” Wustenhoff testified.

CPR failed. Simmons was pronounced dead at Mather Hospital in Port Jefferson.

Brett Klein, a lawyer for Simmons’ family, asked Poltorak, now a sergeant, whether he thought, in retrospect, that Simmons had been struggling to breathe.

“Now, I guess, I would have to believe that. I don’t know.”

In the overnight hours after Simmons died, officers who were at the group home gathered in an office at the Seventh Precinct building in Shirley. They discussed what had happened and prepared their supplementary reports in each other’s presence.

The discussions ran counter to best practices that called for questioning witnesses individually before they spoke with one another.

“That should not have happened,” Cilento said.

The officers were joined by a lawyer affiliated with the PBA and a union delegate, Officer David Samartino, who reviewed the written reports, according to officers’ testimony.

“Just if I used a word that I wasn’t sure of, I’m sure they told me how to better state it,” Cataldo testified about the PBA representatives.

Grenia wrote in her report that Simmons was “on his side” while the officers were struggling to restrain him. Testifying later, she acknowledged she would have been more accurate to say that Simmons was “partly prone.”

Suffolk police Det. Sgt. Edward Fandrey took charge of the investigation.

Cilento said the department should have enlisted an independent law enforcement authority, such as the state police, to take over the case. At the time, the attorney general’s office did not immediately assume the investigations of police-involved deaths.

“Do you really want one of your own detective sergeants investigating local patrol cops?” he asked. “You can never have 100% ethical conduct, because the instinct for self-preservation is always going to kick in.”

Fandrey arrived at the precinct several hours after officers had gathered there. He testified in the lawsuit that he addressed the officers as a group and spoke to them individually. He also acknowledged:

“You don’t want the officers to be comparing their perspective of what happened with other perspectives of what happened.”

He suggested that the presence of the union lawyer limited his ability to get completely independent statements.

“Practically speaking, while you certainly would like to get to a witness before they had the opportunity to share their perspective with another prospective witness, the fact that the common denominator in this is the attorney in all of them kind of waters that down,” Fandrey testified.

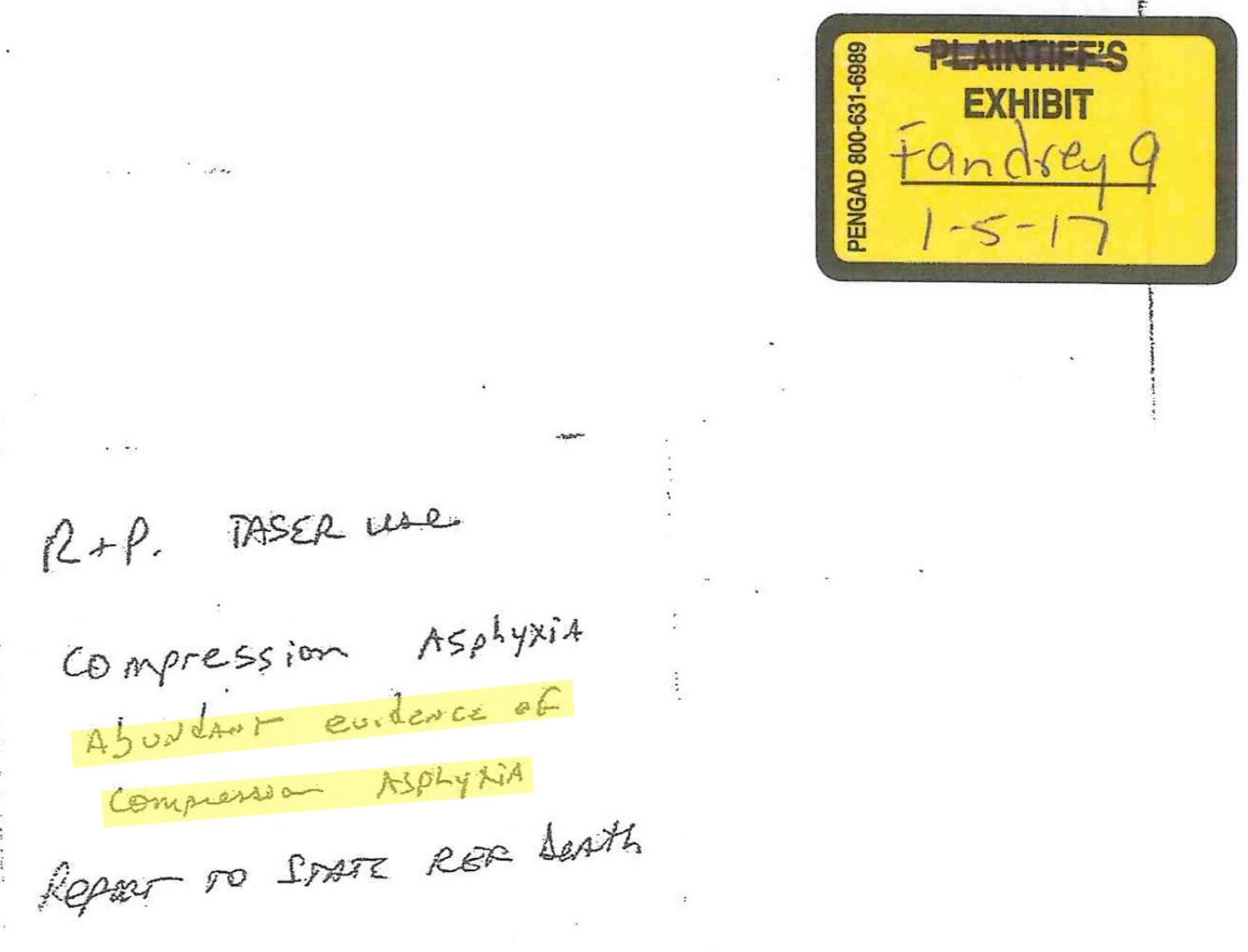

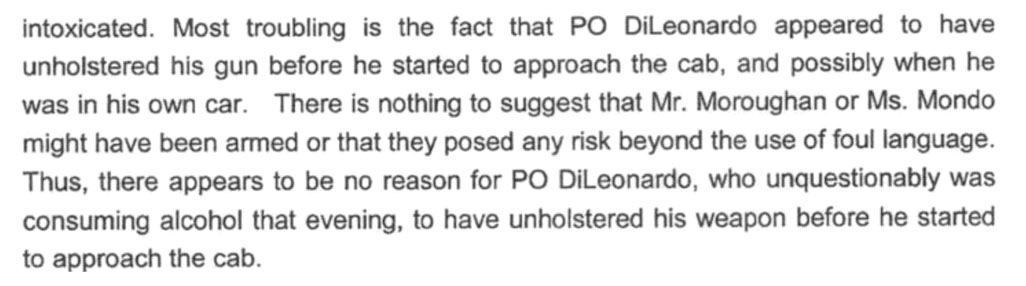

A deputy medical examiner told Fandrey there was ‘abundant evidence of compression asphyxia.’Fandrey’s notes

According to Fandrey’s notes, Dr. Maura DeJoseph, then a deputy county medical examiner, told another detective that her initial observation of Simmons’ body had found evidence of suffocation in tiny spots of bleeding, called petechial hemorrhaging, on Simmons’ “shoulder and outside and inside of his eyelids, which is indicative of chest compression not caused by CPR.”

Days later, DeJoseph told Fandrey directly in a phone call that she had found “abundant evidence of compression asphyxia” — a statement Fandrey memorialized on a sticky note.

Ultimately, DeJoseph classified Simmons’ manner of death as “homicide (injured by others)” and the cause as: “Sudden death during violent struggle including prone positioning and chest compression in a person with obesity with hypertensive cardiovascular disease.”

In lawsuit testimony, DeJoseph cited bruising between Simmons’ eyebrows as one piece of evidence that Simmons had been prone. She said Simmons’ positioning and weight made it “more difficult for [the] chest to expand during respiration” and that it was “the body weight of other individuals that resulted in compression of the body of Mr. Simmons.”

Fandrey had his own theory, which he admitted DeJoseph consistently “minimized.”

He testified that he “very quickly” came to believe Simmons’ own exertion could be a factor in his death, a conclusion that would help to protect the officers from potential criminal liability.

He stated that he thought Simmons’ “excited state” “would be where we would be going” because, he said, he had handled cases in which “people just exhibit this physical exertion and die as a result of that exertion.”

Cilento said that homicide investigators rely on medical examiner findings, not their own theories.

Pearson, the former Miami-Dade prosecutor who has also worked in civil rights law, said Fandrey “was trying to bend the evidence to fit his narrative, rather than looking at the scientific opinion from the medical examiner . . . He clearly rushed to judgment because he did not want this to be a bad in-custody death.”

Fandrey prepared a witness statement from group home worker Brittany Jones. She asked to revise her initial remarks to say both that she wished police had done a better job and that officers had been on top of Simmons for “an extended period of time.”

Fandrey amended Jones’ statement to include her general criticism of police but did not include her more specific account of the officers being on Simmons for an extended time.

“Why didn’t you have her do a second statement about that?” Eric Hecker, a Simmons family lawyer, asked Fandrey.

“I did not, no reason,” he responded.

Fandrey noted in a case report that the officers had struggled with Simmons for an estimated nine minutes in the kitchen, but he did not mention that the fatal portion of struggle while Simmons was handcuffed behind the back and pinned to the floor had lasted an additional nine minutes.

‘Nine minutes is a long time.’

David Klinger, University of Missouri-St. Louis criminal justice professor

Credit: David Klinger

David Klinger, a University of Missouri-St. Louis criminal justice professor who has studied police use of force, said Fandrey’s investigation should have focused on the final minutes.

“Nine minutes is a long time,” said Klinger, who also served on the Los Angeles police force. “That suggests to me that I need to know why it is that they weren’t able to clearly get him to the side, attempt to get him in a seated position.

“It may be that there was no legitimate opportunity. It may be that there were opportunities that they missed. And that’s why you have to get as much fine-grained information as possible before drawing any sort of decent conclusion about the appropriateness of what they did.”

Fandrey completed his investigation with a finding of no criminality by the officers, finding that they did not know the critical information that Simmons was severely autistic and nonverbal.

In his final report, he wrote: “… what the officers correctly perceive as Dainell attempting to elude them at first, likely morphed, once they were on the foyer floor, into Dainell struggling to breathe with the weight of these officers on top of him, but he could not verbalize this. He continued to aggressively struggle, and the police continued to exert more physical pressure to control him.”

Glynice Simmons said she felt police never seriously considered the possibility that officers had been criminally negligent. She said they asked whether her son had a criminal record.

“They were looking for something that he did wrong, that would justify what had occurred to him that night,” she said.

Spota’s office presented Simmons’ case to a grand jury. Grenia, Cataldo and Oliva retained lawyers through the PBA. They agreed to testify, with Cataldo saying in her lawsuit deposition that she believed she waived immunity from prosecution. Oliva said he couldn’t recall if he did and the issue of immunity was not raised during Grenia’s deposition.

Assistant District Attorney Peter Timmons led the grand jury presentation.

Typically, defense lawyers prepare clients to answer questions before a grand jury that could vote on criminal charges. Here, Fandrey helped prepare them to testify, according to the officers’ lawsuit testimony.

Grenia, Oliva and Cataldo described meetings with Fandrey with police union representatives present.

Cataldo recalled a nearly three-hour meeting with Fandrey, Grenia and Oliva at which she listened to 911 tapes and described her role in the struggle. She also remembered a one-on-one meeting with Fandrey. There, he told her questions he thought the district attorney would ask and discussed “how to explain” the events leading up to Simmons’ death, Cataldo said.

Oliva said that during the criminal investigation Fandrey texted him messages that were “supportive in nature” — “if you have questions or concerns, that kind of thing.”

The experts said Fandrey appeared to be guiding the officers to protect them from jeopardy.

“It demonstrates collusion. You can’t do that,” Cilento said. “District attorneys prep you to testify. Not cops.”

Pearson said: “It becomes an issue of witness tampering. What did you tell them? Did you coach them? Did you get them to change their testimony?”

Testifying about the role he played in the grand jury investigation, Fandrey said that he “facilitated the witnesses getting there, I submitted subpoenas. I acted as a clerk. … I was a foot soldier.”

Cataldo said that she, Grenia and Oliva also met with Timmons for about 10 minutes on the day Cataldo testified, with Fandrey and Samartino, the union delegate, and possibly a union lawyer also present.

She agreed with an attorney for the Simmons family describing the session as testimony preparation. She also agreed with his paraphrasing of Timmons as telling her, “I will ask you some questions about what happened” on the day the officers struggled with Simmons.

Fred Klein said that defense lawyers rarely allow their clients to speak with prosecutors when the prosecutors are seeking information that could build a case against them.

“Normally, the attorney representing the cops is not going to let the ADA have a shot at them beforehand,” he said. “That to me was very unusual and indicated to me that the whole prosecution was geared toward making sure that the outcome was not an indictment.”

Ric Simmons is an Ohio State University law professor and former Manhattan assistant district attorney who has studied the grand jury system, including in police deadly force cases. He is not related to Dainell Simmons.

“It suggests that there wasn’t the adversarial relationship that you usually have between the prosecutors and the defendant,” he said.

One key figure did not testify before the grand jury.

Timmons presented the case about 18 months after Simmons died. By then, DeJoseph, the deputy medical examiner who had conducted Simmons’ autopsy, had taken a job with Connecticut’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. She confirmed in her deposition that she was not asked to testify.

Instead, Timmons called Dr. Michael Caplan, who started as chief county medical examiner a year after Simmons’ death.

Fandrey testified that Caplan was “less enthusiastic” than DeJoseph had been that chest compression had been a cause of Simmons’ death. Fandrey said he believed that Caplan “aligned himself more with my thoughts but not completely” that Simmons’ own “physical exertion” had killed him.

DeJoseph, who declined to comment for this story, testified that she never spoke to Caplan about her autopsy findings. Reached by Newsday on his cellphone, Caplan, who now works in Ohio, declined to comment without reviewing his grand jury testimony, which he had yet to obtain from the district attorney’s office.

Timmons left the district attorney’s office in 2018. In an email, he wrote that he was barred by law from discussing grand jury proceedings. He also wrote that anyone who wished to have a lawyer present when speaking with him “would have been afforded that opportunity,” and that witnesses who waive grand jury immunity are entitled to have an attorney.

“It’s nearly unforgivable that they did not get the medical examiner who conducted the autopsy to testify at the grand jury,” Cilento said. “If she herself was deceased, that’s one thing. But if she’s alive and breathing, she should have been in the grand jury.”

Klein said that he saw no reason in the available evidence for not calling DeJoseph to the grand jury.

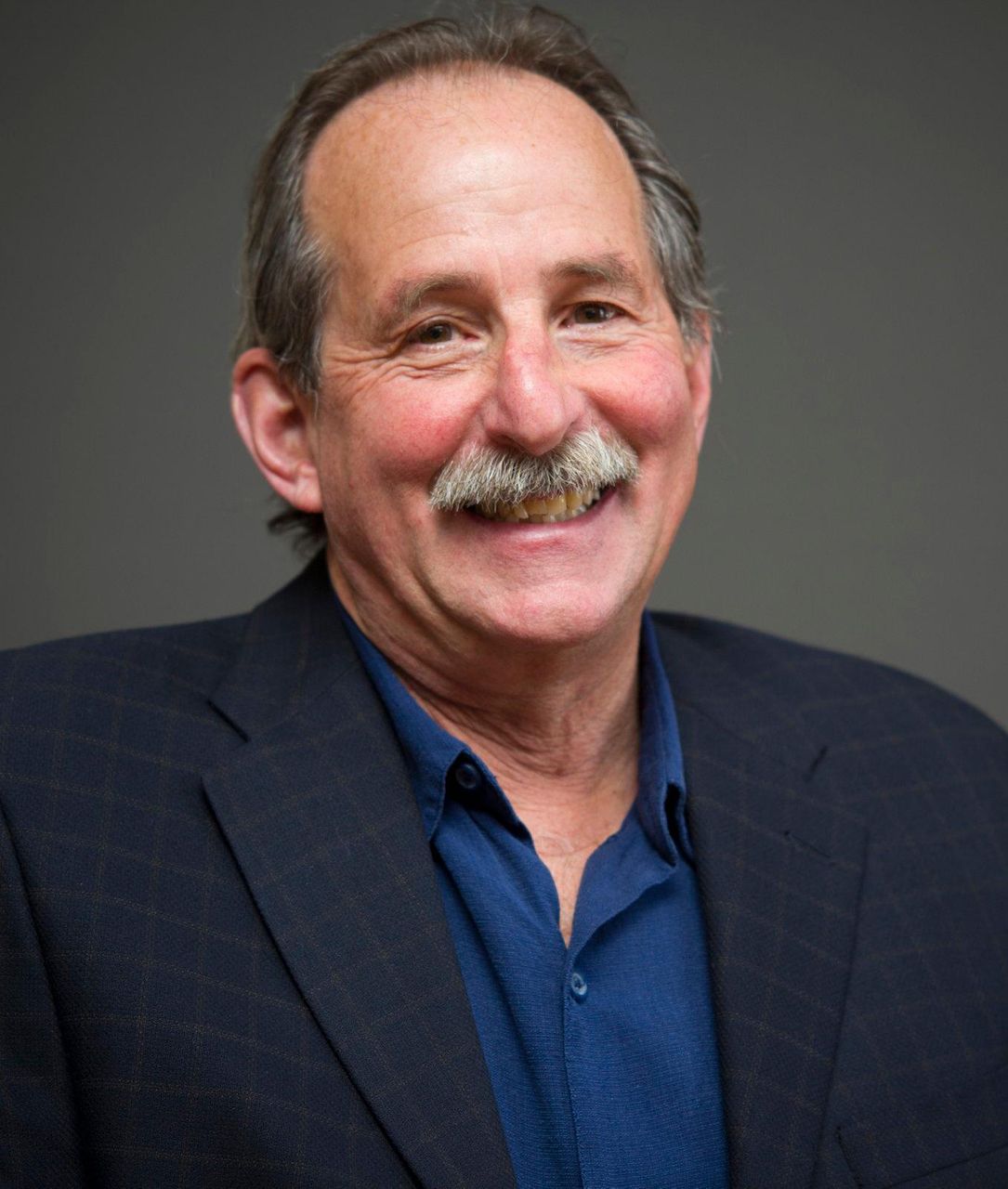

‘It may very well be a smoking gun showing that this case was presented with the idea of not obtaining an indictment.’

Fred Klein, former chief of the major offenses bureau of the Nassau DA’s office

Credit: Newsday/John Paraskevas

“It may very well be a smoking gun showing that this case was presented with the idea of not obtaining an indictment,” he said.

“You have the M.E. that had an opinion that there was a criminal cause of death here and you don’t call that person? And now you call another M.E. that wasn’t even on the job when this occurred and didn’t participate in the autopsy, didn’t speak to the M.E. that performed the autopsy, and now has an innocent explanation for the death?”

“What does that tell you about the direction that this prosecution was taking?”

Stewart, the group home manager, testified before the grand jury. He concluded that the prosecutor tried to shift responsibility for Simmons’ death off the officers and onto the group home staff and Simmons himself.

‘They tried to make it seem as if it was our fault.’

Miles Stewart, group home manager at the time of Simmons’ death

“They were trying to discredit me. They tried to make it seem as if it was our fault,” Stewart said, adding, “I was like, ‘Wow, wow, I would have died. If I was tased and pepper sprayed, and then not allowed to breathe, and they’re going to say it’s because you had high blood pressure in 2008? That’s what they were trying to do. I was like, ‘You got to be kidding me.’ This guy was in shape.”

Glynice Simmons met once with prosecutors and investigators, before the grand jury proceedings began. She grew frustrated after they largely rebuffed requests for information. She recalled telling them that she came from a family that included corrections and parole officers and quoted the first prosecutor assigned to the case as saying:

“‘You are not going to get any justice through the court system except civil court.'”

Timmons said in an email that he never spoke with Glynice Simmons nor was present during any conversation where that comment was made.

Pearson said the statement suggested that prosecutors were “operating in bad faith” if the grand jury had indeed not yet completed its investigation.

“They knew they were structuring the case in such a way that ‘no true bill’ was going to come back,” she said, using a phrase that means no indictment.

Klein said: “I think they manipulated the whole investigation and grand jury presentation to make sure they got the outcome they wanted, which was no criminal prosecution.”

Klein and Pearson, the two former prosecutors, split on whether the information indicated that any of the officers who held Simmons to the floor could have been held criminally liable.

Pearson said a full police and grand jury investigation had the potential to support criminally negligent homicide charges.

“You have a situation here where the person was nonverbal and could not beg for their life. So, all he could do was push and twist and pull,” Pearson said, adding that “officers are trained, they’re only supposed to leave people in that position for short amounts of time because of the fact that they’re not able to breathe.”

Klein said the information did not indicate that the officers had been grossly negligent, a necessity for a criminal charge.

“Here, you’ve got police officers who were doing their jobs, maybe not in the best way possible, maybe with a lack of training, but they’re doing their jobs,” he said, adding, “Given the nature of these struggles where it’s second by second, you don’t have a lot of time to think about it, it’s very hard to make out that a police officer doing their job in a struggle, which is basically justified, is grossly deviating from what a reasonable person would do.”

How internal affairs investigated

After someone dies in police custody, best practices call for parallel reviews by internal affairs investigators, homicide detectives and prosecutors, according to the former law enforcement officers and prosecutors who reviewed Newsday case summaries.

An internal affairs investigation examines whether police misconduct or defects in training played a role in the death.

Sorett, the former Manhattan ADA, said homicide detectives and an assistant district attorney would investigate a death in an NYPD precinct. Simultaneously, internal affairs would start its investigation while waiting to interview officers who may have violated criminal law.

“You want to preserve people’s accounts as soon as possible,” Sorett said.

Sgt. Christopher Love was assigned to lead an internal affairs investigation into how McDonnell died. Internal affairs Lt. Thomas Kenneally accompanied Love to the precinct hours after the death.

Kenneally took no notes and didn’t examine McDonnell’s cell or the area where the struggle took place, he testified.

Similarly, Love testified that he interviewed no one, took no notes and did not examine the pill bottles brought by McDonnell’s mother.

Love then waited for homicide detectives to close their case before he started investigating. By then, 15 months had passed.

‘You would never see an interview in a criminal case that only lasts two minutes.’

Gary Raney, former Idaho sheriff and member of the National Corrections Commission

Credit: Raney Family

Raney, the former Idaho sheriff, said internal affairs cases should proceed at the same time as the criminal investigation.

“There’s no legitimate reason to wait for a criminal investigation to be complete before creating administrative findings,” he said. Beyond disciplining officers, he added, “administrative findings should ask, ‘Is there anything we can do to prevent this from happening again?'”

By law in New York, police departments have 18 months to file disciplinary charges. The 15-month delay left Suffolk internal affairs with three months to act if charges were warranted.

Love testified that he never spoke to the officers, never questioned prisoners who shared the cellblock with McDonnell, and based his investigation on the officers’ written reports.

Then-Deputy Insp. Michael Caldarelli became commanding officer of internal affairs when the case was on the brink of the 18-month deadline.

Caldarelli said previously in Newsday that the unit lacked enough staff to investigate allegations of police misconduct. The 18-month deadline passed without the investigation complete.

Caldarelli testified that he asked Love to continue.

Love filed a report for review and left IA a few months later, he testified.

The report stated incorrectly that McDonnell’s pill bottles had no labels when they were dropped off at the precinct. Testifying, he stated incorrectly that officers deployed Tasers “because Mr. McDonnell was in a violent state, and they had no other way to subdue him without injuring him.”

In January 2014, a federal court magistrate ordered Suffolk County to give copies of its internal affairs files to lawyers representing McDonnell’s family.

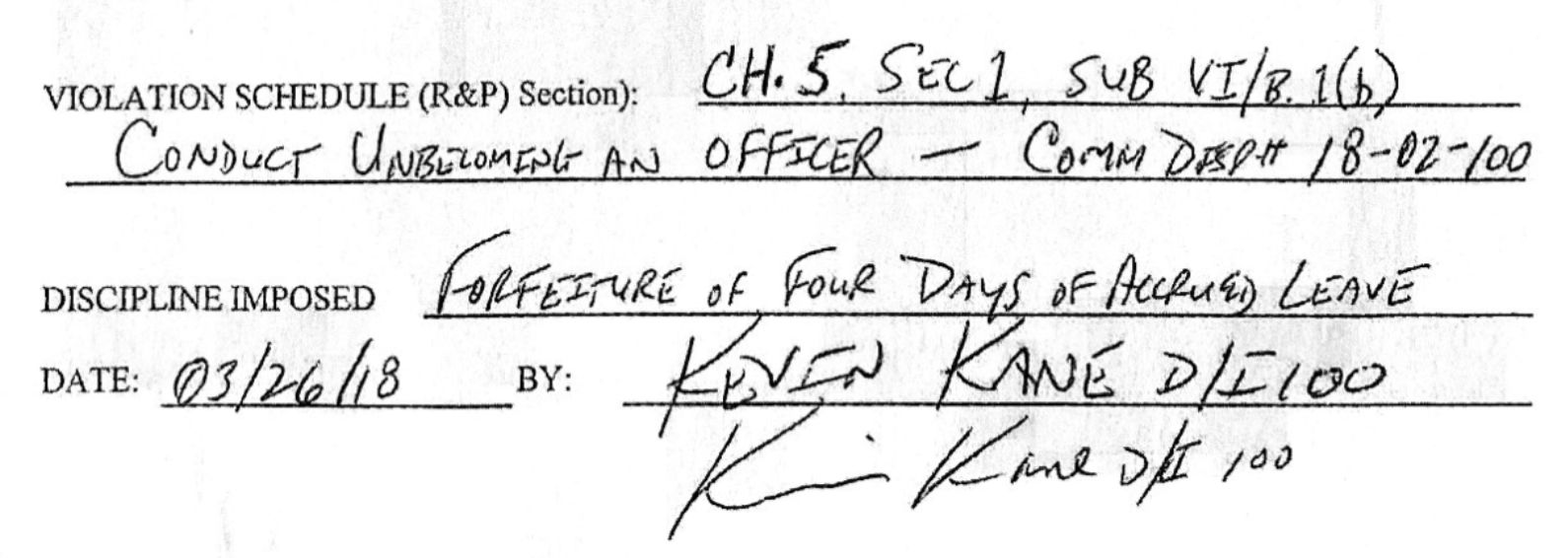

Caldarelli completed the investigation using information contained in lawsuit testimony and a Commission of Corrections report. Thirty-three months after McDonnell’s death, he substantiated 10 misconduct allegations.

Most seriously, he found that Papillo failed to verify McDonnell’s prescription or transport him to a hospital; that Scrima failed to ensure that McDonnell received immediate help after he stopped breathing; that Bressingham used the Taser without participating in required training; and that the police department had failed to establish protocols on cell extractions and the use of Tasers, including discharging Tasers multiple times against the same individual.

Caldarelli concluded that a possible charge that officers had used excessive force was unsubstantiated, meaning that it could not be proven or disproven.

Because internal affairs had missed the 18-month deadline, Caldarelli concluded that the department’s “only available option” was to counsel the officers about proper procedures.