Category: Long Island

A Chat with Tessa Bailey

Drayton

Inside Internal AffairsSuffolk DWI police officer drank, drove, crashed, injured driver, refused breath test — yet escaped arrest

Newsday investigation reveals department punished Officer Weldon Drayton Jr. with loss of four vacation days for refusing a breath test after Central Islip crash. Injuries to Julius Scott are permanent. Commissioner Rodney Harrison calls findings “deeply disturbing.”

Off-duty Suffolk County Police Officer Weldon Drayton Jr. joined fellow members of the Central Islip Volunteer Fire Department in a St. Baldrick’s cancer-research fundraiser with beers at various bars across an afternoon and into the night. Then there was a call about a fire in Central Islip.

Drayton — a drunken-driving enforcement officer in Suffolk’s Highway Patrol — took the wheel of his Volkswagen with a friend and fellow firefighter in the passenger seat and sped toward the house fire, according to a police department internal affairs report obtained by Newsday.

On the way, he crashed into a Honda driven by 20-year-old Julius Scott, pushing Scott into the back seat, stripping the skin from the top of his head, wrapping the car around a light pole, and trapping Scott in the car’s twisted frame. Scott was less than a block from home.

Scott’s mother, Isabel Scott, heard the crash. A neighbor pounded on her door, screaming about Julius. Isabel Scott rushed to the scene and found her son fading in and out of consciousness. She lifted his torn scalp to cover his exposed brain matter and held his hand.

“I was scared, I was scared. I didn’t know if he died on me, or what,” she told Newsday.

Ambulances, fire trucks and specialized rescue crews arrived. They used a hydraulic device known as the Jaws of Life to extricate Scott. A helicopter airlifted him to Stony Brook University Hospital, a regional trauma center.

Police department protocol called for investigating the circumstances of the crash — including whether Drayton had caused near-fatal harm while driving under the influence of alcohol.

Instead, Suffolk police shielded a fellow officer from potential enforcement actions typically faced by civilians. Those could have included a drunken driving-related arrest, suspension of the driver’s license he needed to function as an officer and, most seriously, a felony assault charge, according to attorneys who defend drivers arrested for alcohol offenses.

The police department action, and inaction, after the crash are detailed in the internal affairs report.

“There’s no question objectively that things weren’t done by the book, and they were objectively done to benefit without a doubt a member of the police department,” said John T. Powers, a West Islip-based attorney who specializes in clients charged with driving while intoxicated and teaches continuing legal education courses on the subject.

Three years after the crash, then-Suffolk Police Commissioner Tim Sini honored Drayton for making the most DWI arrests in the First Precinct in 2016.

For Scott, the outcome was very different. Stony Brook doctors treated him in a medically induced coma for three days and kept him hospitalized for about a week. He suffered traumatic brain injury and damage to disks in his spinal cord.

Today, eight years after the 2014 crash, he lives with frequent headaches, throbbing pain emitted by scarring that extends from the front of his head to the back, and daily back spasms. He suffers mood swings and anxiety, especially about getting into other people’s cars. He is terrified of dying in his sleep, he said.

From trauma to anger

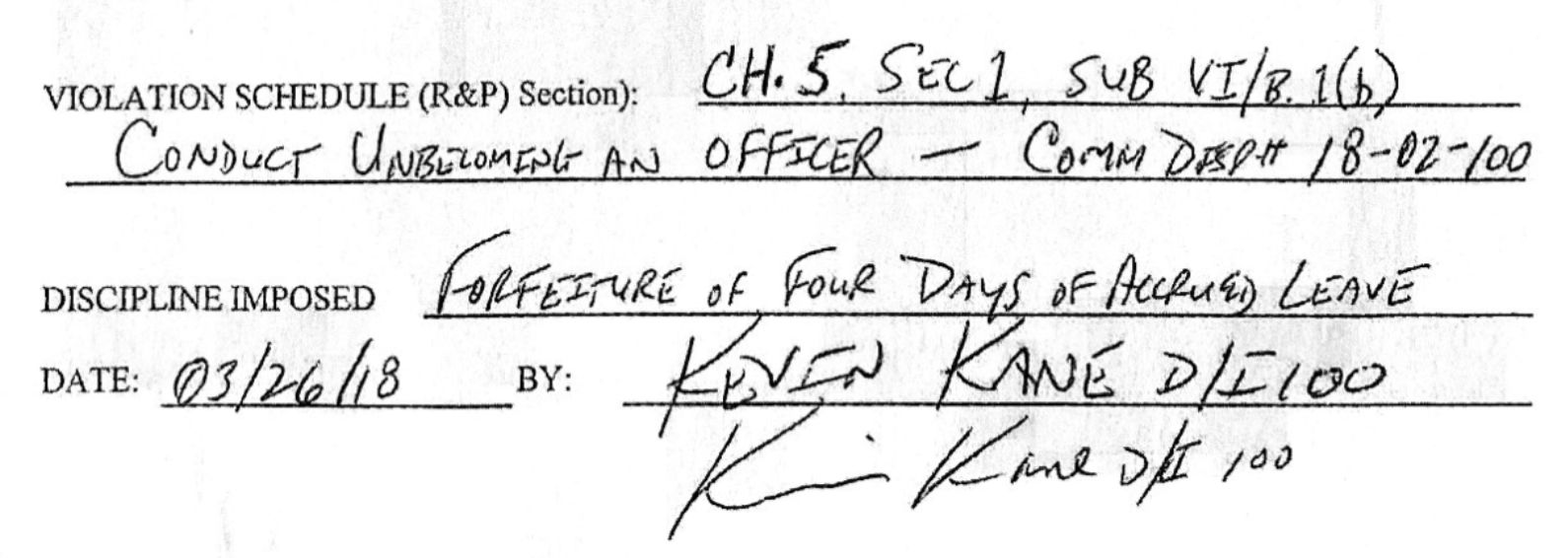

Drayton was penalized with the loss of four day’s pay or vacation time and a $150 ticket for refusing to submit to a field breath test.

Newsday left messages seeking an interview via email and on Drayton’s home and cell numbers. He did not respond.

The contrast between the permanent harm Drayton inflicted on Scott and the punishment meted out to him matches the central finding of Newsday’s Inside Internal Affairs investigation: The Nassau and Suffolk county departments have permitted officers to escape without discipline, or with minimal penalties, even in cases involving deaths or serious injuries.

For a half century, police disciplinary files in New York were sealed by law. In 2020, after a Minneapolis officer killed George Floyd, former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo and the Legislature enacted statutes that they said opened the records to public view.

Invoking the Freedom of Information Law, Newsday then asked the Nassau and Suffolk police departments to release internal affairs documents related to specific officers and events, as well as data that tracks internal investigations from complaint to resolution. The records requests covered Drayton’s case.

The Nassau department claimed continuing power to withhold almost all internal disciplinary records. The Suffolk department maintained that it was obligated to release records only in cases where charges had been upheld against officers. Newsday is waging lawsuits against both departments with the goal of establishing that the public has a right to review how Long Island’s police forces police themselves.

After a delay extending almost 10 months, Suffolk’s department turned over a heavily blacked-out copy of the Drayton internal affairs report. The document revealed that the investigation substantiated a charge of conduct unbecoming an officer against Drayton.

It was only then that Scott learned through Newsday of Drayton’s punishment.

“My life was worth four sick days?” he asked in an interview.

From the editors

Long Island’s two major police departments are among the largest local law enforcement agencies in the United States. Protecting and serving, the Nassau and Suffolk County police departments are key to the quality of life on the Island – as well as the quality of justice. They have the dual missions of enforcing the law and of holding accountable those officers who engage in misconduct.

Each mission is essential.

Newsday today publishes the fourth in our series of case histories under the heading of Inside Internal Affairs. The stories are tied by a common thread: Cloaked in secrecy by law, the systems for policing the police in both counties imposed no, or little, penalties on officers in cases involving serious injuries or deaths.

This installment reveals that a Suffolk County Police Department drunken-driving enforcement officer drove after drinking, crashed into another car, refused to take a breath test and still escaped arrest. The other driver suffered permanent injuries. The department penalized the officer with the loss of four days of vacation.

Newsday has long been committed to covering the Island’s police departments, from valor that is often taken for granted to faults that have been kept from view under a law that barred release of police disciplinary records.

In 2020, propelled by the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the New York legislature and former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo repealed the secrecy law, known as 50-a, and enacted provisions aimed at opening disciplinary files to public scrutiny.

Newsday then asked the Nassau and Suffolk departments to provide records ranging from information contained in databases that track citizen complaints to documents generated during internal investigations of selected high-profile cases. Newsday invoked the state’s Freedom of Information law as mandating release of the records.

The Nassau police department responded that the same statute still barred release of virtually all information. Suffolk’s department delayed responding to Newsday’ requests for documents and then asserted that the law required it to produce records only in cases where charges were substantiated against officers.

Hoping to establish that the new statute did, in fact, make police disciplinary broadly available to the public, Newsday filed court actions against both departments. A Nassau state Supreme Court justice last year upheld continued secrecy, as urged by Nassau’s department. Newsday is appealing. Its Suffolk lawsuit is pending.

Under the continuing confidentiality, reporters Paul LaRocco, Sandra Peddie and David M. Schwartz devoted 18 months to investigating the inner workings of the Nassau and Suffolk police department internal affairs bureaus.

Federal lawsuits waged by people who alleged police abuses proved to be a valuable starting point. These court actions required Nassau and Suffolk to produce documents rarely seen outside the two departments. In some of the suits, judges sealed the records; in others, the standard transparency of the courts made public thousands of pages drawn from the departments’ internal files.

The papers provided a guide toward confirming events and understanding why the counties had settled claims, sometimes for millions of dollars. Interviews with those who had been injured and loved ones of those who had been killed helped complete the forthcoming case histories and provided an unprecedented look Inside Internal Affairs.

Newsday reviewed the information contained in the internal affairs file with five attorneys who represent clients charged with drunken-driving offenses, a criminal defense attorney and a lawyer who specializes in accidents. They found that police had shielded Drayton by:

- Failing to interview him at the crash scene, including by asking a first important question: Where had he been before the collision?

- Failing to subject Drayton to so-called field sobriety testing that officers use to get an initial read on whether a driver may be impaired.

- Allowing a Suffolk Police Benevolent Association delegate, who was on duty, to take Drayton away from the crash site — in effect buying time for Drayton’s body to metabolize any alcohol he may have consumed.

- Failing to take Drayton into custody after he later refused to submit to a preliminary breath test, or PBT, for alcohol.

- Failing to require Drayton to undergo a chemical breath test or blood testing for alcohol under threat of automatic suspension of his driver’s license, which is typically done when a driver declines to take a prescreen breath test and there are signs the driver is intoxicated.

- Downgrading the classification of the harm suffered by Scott from “serious physical injury” to “physical injury” — the difference between legal definition of felony and misdemeanor drunken-driving offenses.

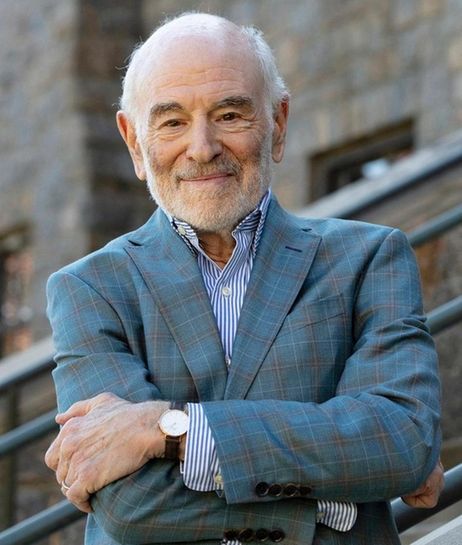

Asked for comment about the findings of Newsday’s investigation, Suffolk Police Commissioner Rodney Harrison, who assumed command of the department in December, wrote in a statement:

“While this incident occurred long before I joined the department, the circumstances surrounding this case are deeply disturbing. My message as commissioner is simple, absolutely no one is above the law and any case with these types of allegations will have my full oversight from start to finish.”

‘The circumstances surrounding this case are deeply disturbing.’

Suffolk Police Commissioner Rodney HarrisonPhoto credit: Howard Schnapp

Suffolk police officials said that the statute of limitations on disciplining officers had expired, ruling out the possibility of reopening an internal affairs investigation of Drayton’s actions.

Drayton joined the Suffolk County Police Department in 2010, after serving in the New York Police Department for three years.

While in the NYPD, he was the subject of six civilian complaints containing 16 allegations, according to New York Civilian Complaint Review Board records.

The complaints alleged that he had abused his authority, including by improperly using force; improperly conducting a personal search; refusing to provide his name and shield number; threatening arrest; making a retaliatory arrest; stopping someone illegally; and discourtesy.

None of the complaints was substantiated. He was exonerated in one case. The complainant and the alleged victim in two cases refused to cooperate with investigations. The NYPD closed three outstanding cases when Drayton resigned.

On the Suffolk force, Drayton won an assignment to the Highway Patrol Bureau’s Selective Alcohol Fatality Enforcement Team, known as SAFE-T, which targets driving while intoxicated. He also volunteered as a Central Islip firefighter.

On March 8, 2014, the Saturday before St. Patrick’s Day, fire department members took part in a fundraising drive for the St. Baldrick’s Foundation, which donates money to research for childhood cancers. The name is derived from the fact that many participants shave their heads bald as part of the event, creating the name of the fictional St. Baldrick.

Drayton acknowledged to internal affairs that he drank that day. He also gave the only recorded account of how much he drank and over how many hours. He stated that from 1 p.m. to 9 p.m. he drank 7.5 beers and then stayed at Fatty McGees bar on Connetquot Avenue in East Islip without drinking until the fire call came in around 10:30 p.m. He did say, however, that he bought drinks for others at the bar.

Less than four minutes after the alarm, he was driving north along Lowell Avenue, a two-lane roadway that runs beside a residential neighborhood next to the Central Islip court complex. The speed limit was 35 mph. A witness, whose name is blacked out of the internal affairs report, reported that Drayton’s car was speeding and not flashing emergency lights.

Volunteer firefighters responding to a call in their personal cars must obey all traffic laws and are not required to display flashing lights, said Ed Johnston, chief of the Suffolk County Fire Academy.

“I saw headlights in my rearview mirror, and then a car passes me really fast. I was going about 40 mph, and the car that passed me was going really fast,” the witness, who had been driving his family home from church, told internal affairs investigators.

The firefighter friend who rode with Drayton told investigators that he “was giving Drayton updates from his phone reference the fire; he believes they were driving at 45-60 mph”

‘[Blacked out] was giving Drayton updates from his phone reference the fire; he believes they were driving at 45-60 mph.’Internal affairs report

Just then, Scott was trying out a newly repaired Honda owned by his friend Joshua Perez. Scott had come home from a birthday party for an 8-year-old niece at a skating rink, and Perez had suggested that he take the car for a ride, Scott and Perez said.

Heading around the block, Scott drove west on Satinwood Street and made a left onto Lowell Avenue. Drayton’s Volkswagen came around a curve about a block away and crashed into Scott’s moving Honda.

The impact happened at a right angle, according to a box checked on the police report. The Volkswagen hit the passenger side of the car, not the driver’s side. Scott theorized in an interview with Newsday that Drayton had made a last-moment attempt to swerve to avoid the collision.

Neighbors rushed to the scene. Some had been outside talking with members of Scott’s family, who had also come home from the birthday party. When Isabel Scott arrived, she saw flashing lights only on an arriving ambulance, she said. A police officer, whose name is blacked out, told internal affairs that the scene was “chaotic” and that “the bystanders were yelling and angry about the crash.”

Speaking with Newsday, Isabel Scott said that friends and family grew anxious because removing her son from the wreck seemed to take a long time.

“I had to calm them down, keep myself calm, and calm them down to get them away from the scene. Because they, the police, had no control over the crowd,” she said.

Drayton suffered no visible injuries. His passenger’s head hit the windshield and sustained a cut. Perez said there was little damage to Drayton’s car: The windshield was cracked, and the bumper and hood had small dents.

Facing angry neighbors while Isabel Scott cradled her son, Drayton got into a police car. She said Drayton never tried to help her son.

“Not one time did he come over here and find out. You’re a firefighter — he could have controlled that whole scene — but he didn’t,” she said.

After car crashes involving serious injuries, standard protocols direct officers to question motorists about, at a minimum, where they had been before the collision. That type of questioning would have placed Drayton at the St. Baldrick’s festivities, Powers said.

If police believe that motorists have consumed alcohol, the protocols require officers to observe whether the drivers have glassy eyes, are unsteady on their feet or have slurred speech, and to administer field sobriety tests, according to attorneys who represent drivers charged with driving while intoxicated.

There are three commonly used field sobriety tests: a gaze exam, in which an officer observes how eyes follow an object moving across a person’s horizontal field of vision; the walk and turn test, which involves taking nine heel-to-toe steps in one direction and back; and the one-leg stand, said Maxwell Glass, a criminal defense attorney who has taken the police field sobriety training courses.

Three ambulances arrived at the scene, along with fire trucks and police emergency vehicles. Drayton stayed in or around the police car.

The PBA delegate, Officer Jerome Linder, arrived around 11:30 p.m., having left his work shift in his personal car, even though he was on duty. Without informing police supervisors or seeking permission, he drove Drayton away from the crash site to Southside Hospital, according to the internal affairs report.

Drayton had not been questioned or tested. He later told internal affairs that he had complained to Linder that his shoulder, neck and back were starting to bother him.

Robert Brown, a criminal defense attorney and former New York Police Department captain, said Linder’s involvement suggests that Drayton feared alcohol testing.

“If I’m sober and I’m an active-duty member of the department, and I’m in a fender bender, why would I call my union rep?” Brown asked.

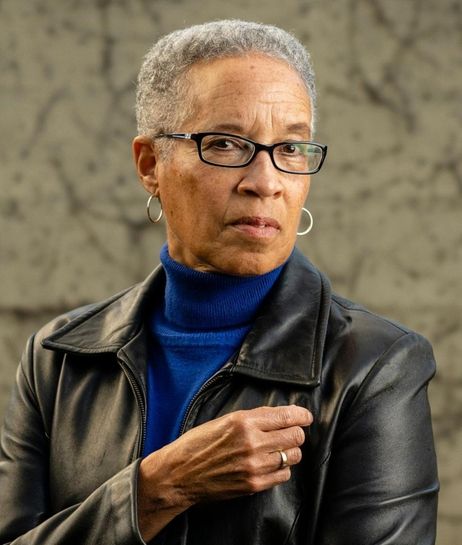

‘How is it that there wasn’t proper investigation done in a timely manner?’

John T. Powers, drunken-driving defense attorneyPhoto credit: Alejandra Villa Loarca

Powers said: “How is it that there wasn’t proper investigation done in a timely manner at the scene before this person was removed from the scene? That is what is most surprising to me and most alarming to me.”

He added, “To me, the only reason Linder takes Drayton from the scene is that he suspects that this guy is intoxicated, or has been drinking, or else he would leave him at the scene.”

Linder did not respond to interview requests.

The attorneys also challenged an internal affairs finding that Drayton showed no evidence of alcohol use.

Some also questioned the account Drayton later gave to internal affairs of drinking 7.5 beers over 7.5 hours, a rate of consumption that, they said, would indicate he stayed sober all the time.

Powers pointed out, for example, that people rarely describe their consumption in halves and that the body typically expels the equivalent of one beer an hour.

At about 11:50 p.m. — roughly 20 minutes after Linder arrived — officers discovered that Drayton was gone, according to the internal affairs report.

After 20 more minutes — at around 12:10 a.m. — an officer called Linder’s cellphone. The call dropped. Eight minutes later, Linder called back and reported that he was at Southside Hospital with Drayton. Two more union officials met Drayton there.

At 1:10 a.m., more than two-and-a-half hours after the crash, a supervisor ordered officers to ask Drayton to submit to a preliminary breath test, the PBT, according to the internal affairs report. The Suffolk police department blacked out the supervisor’s name.

‘[Blacked out] evaluated Drayton’s state of sobriety, and requested that Drayton submit to a pre-screen breath test. Drayton refused this test.’Internal affairs report

The test entails breathing into a cell-phone-sized device that produces an initial reading of a driver’s alcohol level. Because it is an approximation of alcohol content, a PBT reading is not admissible as evidence in court.

Highway officers like Drayton regularly ask drivers to take pre-breath tests. They do so when they have reasonable suspicion that the motorists have consumed alcohol. If there is no indication of alcohol consumption, officers typically do not seek to administer the test, lawyers said.

“If they’re asking for a PBT, there has to be a reason,” Glass said.

Drayton refused to take the test. When drivers say no to the PBT, officers typically take them into custody and transport them to a precinct for more sophisticated chemical breath testing. Suffolk police used a device called an Intoxilyzer.

‘He should have been arrested.’

Jonathan Damashek, vehicular accident legal expertPhoto credit: Matt Reese

“He should have been arrested,” said Jonathan Damashek, a New York City-based attorney who specializes in car and truck accident cases.

Powers agreed: “They would tell you, ‘You’re under arrest. Put your hands behind your back. We’re bringing you in.'”

An Intoxilyzer, as a calibrated chemical test, is considered more accurate than a pre-breath test and is admissible in court. Refusal to take that test results in an automatic one-year license suspension.

“That did not happen in this case. The sole reason was he is a police officer,” said Michael Brown, who represented Scott in a lawsuit alleging that Drayton had been negligent behind the wheel while responding to a fire and the Central Island Fire Department had been negligent in supervising him.

If a driver has seriously injured or killed someone and refuses to take an Intoxilyzer test, police will seek a court order for a blood test to determine alcohol consumption, Sills said.

Asked why police didn’t seek a warrant for drawing Drayton’s blood, the department wrote in an emailed statement that police need “reasonable cause to believe” that a driver is intoxicated to apply for a warrant.

The department also wrote: “The IA report indicates that, based on the accounts of witnesses and involved members of the department, Officer Drayton did not evince any indicia of intoxication.”

A department spokesperson had no response when asked why police asked Drayton to submit to a prescreen breath test — which requires officers to have grounds to suspect intoxication.

Two days after the crash, internal affairs opened an investigation into whether Drayton and Linder had violated departmental regulations. The file indicates that it included a review of police documents and interviews with 10 witnesses, including three civilians and five officers, plus Drayton and Linder.

Those records show that Drayton told internal affairs he did not recall being asked to take a breath test — and that the lead investigator did not believe him.

“Drayton’s inability to recall these events is simply not credible, given his otherwise extensive recall of events both before and after the crash, as evinced in his interview,” Lt. Peter Ervolina wrote.

‘Drayton’s inability to recall these events is simply not credible.’Internal affairs report

According to the report, Drayton also said that he had moved among bars on a day off from work and had limited his socializing after 9 p.m. to buying drinks for others at Fatty McGees, none for himself.

Drayton told internal affairs that an officer offered him a seat in a patrol car to prevent a conflict with bystanders and that Linder suggested going to the hospital. Drayton also said that he remembered the three PBA officials who joined him at the hospital but didn’t recall being examined by a doctor.

The file also reveals that police on the scene made a determination that has potential legal consequences: They classified the crash as having caused “serious physical injury,” a designation that opens a drunken driver to felony prosecution.

Later, however, police downgraded the harm inflicted on Scott to “physical injury,” a misdemeanor designation, according to a memo sent by Internal Affairs Bureau Capt. Kevin Foley to Insp. Armando Valencia, the bureau’s commanding officer.

Asked to explain the change, the department wrote in an email that a detective “was advised by hospital staff that Scott’s injuries were non-life threatening.”

The state Penal Law defines serious physical injury as an injury that “creates a substantial risk of death,” lasting damage to health or lasting impairment. A drunken driver who causes that level of harm can be charged with the felony of vehicular assault. A drunken driver who causes physical injury — meaning “impairment” or “substantial pain” — is guilty only of misdemeanor assault.

It is a significant distinction when it comes to compelling a driver suspected of drunken driving to take a chemical test. The presence of just physical injury is not enough to get a warrant when a driver refuses a chemical test, said Eric Sills, an Albany-based attorney who has written a book on handling drunken driving cases.

“Serious physical injury is a prerequisite to a valid court order for a chemical test,” he said.

A month after the crash, internal affairs served Drayton with charges of violating rules and procedures. Whether the charge would be substantiated, and what his punishment would be, was then up to the police commissioner — except that the police contract gave Drayton the power to demand a ruling by an arbitrator. A hearing was set and then postponed.

In March 2015, Ervolina wrote a memo recommending that a charge of conduct unbecoming an officer be substantiated against Drayton for refusing to take the prescreen breath test. At the same time, his memo concluded that, based on the observations of people at the scene and Drayton’s statement, “Drayton was most likely not impaired at the time of the crash.”

Ervolina declined to comment through a department spokeswoman.

Fully four years after the crash, in March 2018, Drayton accepted the finding and penalty of the forfeiture of four days of accrued time.

‘Discipline imposed: Forfeiture of four days of accrued leave.’Internal affairs report

Suffolk County officials declined to release the arbitration file, and PBA attorney Christopher Rothemich did not respond to an interview request.

It was between the filing of charges and the punishment that Sini commended Drayton for making the most drunken driving arrests in the First Precinct.

Asked if Drayton was given preferential treatment as a police officer, the department said in an email, “The IAB investigation does not indicate that Drayton was afforded preferential treatment.”

Drayton honored for making DWI arrests

Video credit: James Carbone

Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone presented an award in 2017 to Officer Weldon Drayton Jr. as a member of a team assigned to curb drunken-driving. Drayton is no longer on the team.

The records also showed that Linder told investigators he had followed standard union practice in removing Drayton from the crash site.

“Linder felt that responding to a crime scene in his personal vehicle and removing one of the motorists involved in a serious crash at the scene, even though he was not involved in the scene in an official capacity, was common practice for a ‘union official’,” the file states.

Linder claimed that he had not seen the three ambulances at the scene and therefore did not consider having one of them take Drayton to the hospital, according to the file.

The investigation concluded that Linder violated department rules both by leaving his assigned post to go to the crash scene without notifying a supervisor and by driving Drayton away. Internal affairs recommended command-level discipline, which typically covers minor rules violations and can result in penalties including counseling, retraining or loss of accrued time.

By disputing the finding, Linder delayed a final resolution. He retired in 2018, closing the case without action, and collects an $83,228 annual pension.

While the department’s charges against Drayton were still open, the Central Islip Fire Department fought a series of blazes in abandoned houses in the community. In 2018, police accused Drayton and another firefighter of setting the fires. The department suspended him; the Suffolk district attorney’s office took him to trial.

The prosecution collapsed. Suffolk Supreme Court Justice John Collins dismissed the charges after witnesses gave conflicting testimony and the DA’s office admitted it had failed to provide Drayton’s defense lawyers with exculpatory evidence as required by law.

Drayton petitioned to return to duty as a police officer. In June 2020, an arbitrator reinstated him and awarded two years’ back pay. In 2020, his total compensation was $442,651. He filed a federal lawsuit against the department, alleging racial discrimination because he was the only Black man targeted in the arson investigation, according to court papers. The case is pending.

Although Drayton returned to work and is now assigned to the Second Precinct, the internal affairs investigation compromised his ability to testify in drunken-driving cases. The district attorney’s office has alerted defense lawyers in at least seven cases to the internal affairs findings against Drayton, enabling the attorneys to use the information to undermine his value as a witness.

“Can you imagine getting him on the stand?” Damashek said. “His credibility would be impeached immediately. He would get destroyed on the stand.”

Defense attorney Gregory Grizopoulos said that the information about Drayton’s crash helped him win a significantly reduced punishment for a client arrested for allegedly driving while intoxicated: The man would escape with a noncriminal traffic infraction if his record stayed clean for a year.

In 2021, the police department paid Drayton $285,000, according to payroll records.

Scott has been less fortunate.

Left unable to focus well because of brain damage, Scott could not work for more than four years. He took a $14,000 loan to pay his bills and secured a $180,000 settlement of his lawsuit. Jeremy Cantor, an attorney for the Central Islip Fire Department, declined to comment.

Scott now works as an Amazon driver. His friend, Perez, can’t shake the memory of Scott’s cracked skull and swollen face. His mother, Isabel Scott, said that passing the corner where her son nearly died is still “heart-wrenching.”

“I never want to know that feeling of losing a child,” she said.

Scott said he makes a point of enjoying every day because he feels life is a gift now. But he remains angry that Drayton failed to help him immediately after the collision.

“He’s supposed to be a cop. He’s supposed to be a firefighter. He’s supposed to be people that protect us. And he just tried to leave me there,” Scott said.

MORE COVERAGE

Reporter: Sandra Peddie

Editor: Arthur Browne

Video and photo: Jeffrey Basinger, Reece T. Williams

Video editor: Jeffrey Basinger

Digital producer, project manager: Heather Doyle

Digital design/UX: Mark Levitas, James Stewart

Social media editor: Gabriella Vukelić

Print design: Jessica Asbury

QA: Daryl Becker

Understaffed, undermined: Ex-Suffolk internal affairs commander describes how he was driven out

Inside internal affairsUnderstaffed, undermined: Ex-Suffolk internal affairs commander describes how he was driven out

Retired Insp. Michael Caldarelli says department leaders in 2012-14 discouraged him from upholding charges against officers, pressured him to water down findings and denied the bureau the staff needed to properly conduct investigations.

A

former commander of the Suffolk County Police Department’s Internal Affairs Bureau says department leaders discouraged him from upholding charges against officers, pressured him to water down findings in two high-profile cases and denied the bureau the staffing needed to properly conduct investigations.

In Newsday interviews supported by police documents, retired Insp. Michael Caldarelli described the two years he spent heading IAB, from late 2012 to late 2014, as a “Kafkaesque” career-derailing experience.

“A decision has been made to keep internal affairs weak,” Caldarelli said he was told while meeting with then-Commissioner Edward Webber and then-Chief of Support Services Mark White.

With small staffing compared with the strength of internal affairs bureaus in other large departments, Suffolk’s IAB often failed to complete investigations before an 18-month statute of limitations barred disciplining officers. It also stopped reviewing complaint investigations conducted by precinct commanders, about half of all cases, Caldarelli wrote in memos.

A “substantiated” finding indicates that IAB has found evidence an officer was guilty of actions that can range from discourtesy to the use of excessive force. In serious cases, substantiated findings can embarrass the department, generate calls for accountability and provide powerful evidence in multimillion-dollar lawsuits alleging police misconduct.

Eventually, Caldarelli came to believe that the department and the county attorney’s office relied on an ineffective IAB to protect Suffolk from the negative consequences of wrongdoing.

It’s clear to me there are people who seem to feel that internal affairs should be functioning as an organ of defense.

Michael Caldarelli

“It’s clear to me there are people who seem to feel that internal affairs should be functioning as an organ of defense. It cannot be that way. By definition, that’s corruption,” Caldarelli recalled telling Webber in a Newsday interview. “It certainly seemed for a certain period of time the truth was really not what was being sought from internal affairs.”

Webber and White, who are both retired, did not respond to requests for comment.

Webber transferred Caldarelli out of internal affairs in 2014.

In 2021, Acting Police Commissioner Stuart Cameron promoted Milagros Soto, a 33-year veteran of the department, to chief and gave her command of the Internal Affairs Bureau. County Executive Steve Bellone called her a “trailblazer” as the first Hispanic chief in the Suffolk department’s history.

Before she left the position, then-Commissioner Geraldine Hart said in an interview that the department had added investigators to internal affairs and made serving in the bureau a steppingstone to promotions.

In 2014, the department reached an agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice to address allegations of racial discrimination after the beating death of immigrant Marcelo Lucero in Patchogue by a group of teens, most of whom were white. The SCPD agreed to report its IAB staffing, track complaints of discriminatory policing and audit completed misconduct investigations.

In October 2018, a Department of Justice report found Suffolk had substantially met its obligations, with actions that included improved recruitment of investigators and faster completion of investigations.

According to Suffolk police records, the number of cases more than 18 months old fell from 130 in June 2016 to two in September 2021.

Caldarelli was raised in Hauppauge in a family whose members gravitated toward firefighting and law enforcement. Joining the Suffolk department in 1985, he was assigned to the Third Precinct, served for seven years in Brentwood and rose to sergeant, then lieutenant.

In 1997, while he was a lieutenant, the department posted Caldarelli to IAB as an investigator. He said his two years there were free from interference from above.

He became a captain, worked in the chief of the department’s office, supervised patrol officers and served as district commander on overnight shifts before being promoted to deputy inspector. He had worked in five of the seven police precincts in the first 27 years of his career.

Caldarelli took command of internal affairs in 2012 after meeting with then-Suffolk Police Chief James Burke, Chief of Patrol John Meehan and White.

The chiefs gave Caldarelli two mandates, he said.

First, get IAB to complete cases more quickly. Too many cases weren’t being finished within 18 months, ruling out discipline.

Second, get tougher, because IAB had wrongly chosen not to substantiate charges despite evidence that officers deserved discipline.

Told that the department would add five lieutenant investigators to its staff of 13, Caldarelli embarked on his mission.

I did believe that there was an honest desire on their part to make things work well for internal affairs.

Michael Caldarelli

“I did believe that there was an honest desire on their part to make things work well for internal affairs,” Caldarelli said.

Shortly after Caldarelli’s appointment, an FBI investigation targeted Burke for beating a heroin addict who had stolen a duffel bag containing a gun belt, ammunition, cigars, sex toys and pornography from Burke’s departmental SUV. Burke then engineered a monthslong cover-up with the help of top law enforcement officials, including former District Attorney Thomas Spota and top corruption prosecutor Christopher McPartland.

Burke pleaded guilty in February 2016 and was sentenced to 46 months. He was released to home confinement in 2019. Convicted after a trial, Spota and McPartland began 5-year sentences in December.

Caldarelli believes that Burke’s cover-up attempt played a role in keeping internal affairs weak.

“Burke’s situation looms very large in the picture,” he said.

A few days into his new assignment in October 2012, Burke ordered Caldarelli to investigate who in the department had leaked a story to the Long Island Press. The article revealed that, in a turf war with federal law enforcement, the department had pulled three detectives from a federal gang task force that was investigating MS-13.

While deeming it “stupid,” Caldarelli accepted Burke’s command as a legal order. He assigned Lt. Kenneth Fasano, a seasoned investigator. Caldarelli remembers Fasano telling him:

“‘I mean this with no disrespect, but I got to tell you I don’t think this is a good idea.’ And I said ‘Kenny, I couldn’t agree with you more. I don’t know that I would deem it an illegal order; it might be an ill-advised one. But get to it.'”

Fasano scheduled interviews with the three detectives who had been pulled from the task force — Det. John Oliva, Det. Robert Trotta and the late Det. William Maldonado.

Trotta, who served in the department for 25 years and is now a Suffolk County legislator, said Fasano called him at home.

“I didn’t do anything, I didn’t talk to anybody. I don’t know anything,” Trotta remembers telling Fasano. “He said to me, ‘Don’t feel bad, you’re not the only guy [Burke is] after. I feel like I’m in the Gestapo.'” Fasano did not respond to a request for comment.

Oliva said he wasn’t worried, explaining, “We were naive then” about Burke’s corruption.

(Oliva pleaded guilty in 2014 to a misdemeanor charge of official misconduct and was forced to retire for providing information to Newsday in a story unrelated to the gang task force. A federal judge said Spota had “retaliatory motives” for the prosecution. A judge last year tossed out the conviction at the urging of Spota’s successor, former District Attorney Tim Sini.)

For unexplained reasons, Burke called off the internal affairs investigation.

The department promoted Caldarelli to inspector but never delivered promised reinforcements.

When Caldarelli had served as an IAB lieutenant, each sergeant or lieutenant carried 12 to 13 cases at a time. Now, each had as many as 18 cases.

Caldarelli pressed Webber for help in three memos that Caldarelli gave to Newsday.

“In some instances, disciplinary action has not been possible on substantiated allegations due to the 18-month statute of limitations expiring before investigations have been completed,” he notified Webber in April 2013.

“In several recent cases disciplinary action charges have been served just before the statute of limitations expires. This situation has resulted in an atmosphere of near constant crisis in which decisions on discipline must be made very quickly and often on less than complete information.”

He concluded, “The potential for damage to our reputation is very real, as is the specter of substantial civil liability.”

Four months later, in an August 2013 memo, he cited a 2005 Department of Justice survey showing that the Miami-Dade Police Department had one internal affairs investigator for every 30 officers and the Los Angeles Police Department had one for every 37. Suffolk’s department had one investigator for every 182 officers. Today the department has one investigator for every 133 officers.

“The current workload in the Internal Affairs Bureau is unsustainable,” Caldarelli wrote in 2013.

In January 2014, in a yearly memorandum on accomplishments and goals, Caldarelli warned, “Mere survival is the only goal I can reasonably establish for this year.”

In interviews, Caldarelli said he also pressed for additional resources in regular meetings with Webber. At one of those meetings, he remembers that Webber or White remarked that IAB was to be kept weak.

Webber was “tired of telling me no, and he wanted me to know that it wasn’t his decision not to enhance the staffing in internal affairs. And I believe him,” Caldarelli said. He said he never learned who made the decision Webber was referring to.

Toughening standards, as he was ordered to do, met resistance from high-ranking colleagues, Caldarelli said.

I began to get the sense that substantiated cases were really not welcome news.

Michael Caldarelli

“As time went on, I began to get the sense that substantiated cases were really not welcome news,” he said.

Caldarelli recalled that Meehan, the chief of patrol, gave him “a friendly warning” that some inside the department thought he was substantiating too many cases.

“He mentioned to me very casually, ‘Michael, a lot of people are thinking you’re substantiating too many cases. You have any idea what your rate of substantiation is compared to New York City’s?’ And I said, ‘No I really don’t, chief.'”

Caldarelli traces his downfall to two cases.

In the first, Caldarelli substantiated 10 allegations of misconduct in the death of Daniel McDonnell, a Lindenhurst carpenter who died in the First Precinct building after a struggle with officers during a psychiatric breakdown. A state Commission of Correction investigation declared McDonnell’s death “a preventable homicide.”

Caldarelli’s findings, completed 33 months after the death, were turned over to the McDonnell family in its lawsuit against the county. He said that Deputy County Attorney Brian Mitchell told him that he believed Suffolk police hadn’t done anything wrong. Mitchell did not respond to requests for comment.

“I said, ‘Well, you know, thanks, but I think I’m more comfortable with my findings,'” Caldarelli said he responded.

After he testified in a deposition, Caldarelli said, Webber told him that he too questioned some of his key findings.

“I politely told him: ‘Commissioner, I disagree with you. I think we got it right the first time.'”

Three months after Caldarelli produced the report, the county agreed to pay $2.25 million in compensation to McDonnell’s family.

In June 2014, a different judge ordered the department to produce a long-delayed report of its internal affairs investigation into how Suffolk police handled the shooting of Huntington cabdriver Thomas Moroughan by an off-duty Nassau County police officer who had been drinking.

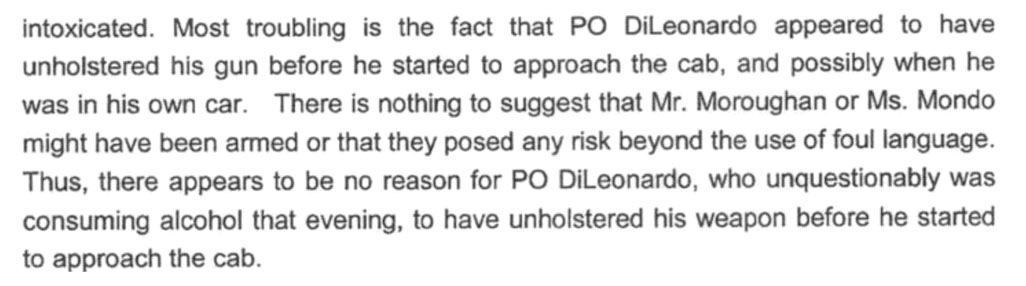

Caldarelli substantiated two misconduct charges against supervisors who investigated the wrongful shooting and arrest of Moroughan. He found that a sergeant failed to investigate whether the shooter, Anthony DiLeonardo, and a fellow off-duty Nassau officer had consumed alcohol that night. He also found that a detective sergeant wrongfully ordered homicide detectives to take an incriminating statement — later discredited — from the cabdriver while he was under the influence of narcotic pain medications.

Webber directed Caldarelli to meet with William Madigan, who was Suffolk’s chief of detectives at the time. Madigan arrived with a copy of Caldarelli’s report. He had marked the document with instructions to delete evidence that Caldarelli said was crucial to substantiating the misconduct findings. A copy of the report obtained by Newsday showed Madigan’s handwritten notes. Caldarelli confirmed the document’s authenticity.

Caldarelli wrote a memo to Webber objecting to the changes and requesting a meeting. Face-to-face, Caldarelli said, he told Webber and White that Madigan’s actions were “totally inappropriate.”

Webber responded that he wouldn’t force Caldarelli to do anything. But Caldarelli also recalled that Webber told him, “I would imagine you’re really not very comfortable being in internal affairs anymore.”

Caldarelli said he answered, “I’m absolutely fine with commanding internal affairs, but if stuff like this is going to continue, no, I’m not. I said, ‘This is madness.'”

A few months later Webber transferred him into a position formerly held by a lieutenant, overseeing an office that develops the department’s rules and procedures. “A broom closet counting thumbtacks,” he said.

Caldarelli retired in 2017 at age 54.

In April 2016, Suffolk Police reported it had added staff to IAB, bringing the unit to 18 investigators, led by three captains — the staffing levels that Caldarelli had been requesting. In September, IAB staffing was lower, with 15 investigators and three investigative captains. On Thursday, the department said its staffing was back up to 18 investigators and three captains.

MORE COVERAGE

Secret file reveals ‘cover-up of a cover-up’ in unjustified police shooting, arrest of innocent man

Inside internal affairsSecret file reveals ‘cover-up of a cover-up’ in unjustified police shooting, arrest of innocent man

Suffolk police brass pressed internal affairs to delete evidence that would support misconduct charges in arrest of cab driver shot by off-duty Nassau officer during Huntington Station road-rage incident.

T

he shooting of a Huntington Station cabdriver by an off-duty Nassau County police officer in a fit of alcohol-fueled road rage has been dogged for more than a decade by evidence of cover-ups and the wrongful arrest of an innocent man.

Former Nassau Officer Anthony DiLeonardo opened fire on cabbie Thomas Moroughan after a night of dinner and drinking in 2011. He wounded Moroughan twice, pummeled him with a pistol, breaking his nose, and faced possible arrest on a first-degree assault charge.

Instead, Suffolk County Police Department investigators initially accepted DiLeonardo’s account that he had shot Moroughan in self-defense. They charged Moroughan with assault after detectives took a hospital-bed statement in which Moroughan purportedly exonerated DiLeonardo and incriminated himself. At the time, doctors had administered narcotic medications to dull Moroughan’s pain.

Behind the scenes of Newsday investigation

The shooting entangled the internal affairs bureaus of Long Island’s neighboring county forces in separate investigations. After more than three years, the Nassau department dismissed DiLeonardo. Separately, it punished fellow Officer Edward Bienz, who was at the scene of the shooting after drinking with DiLeonardo, with the loss of 20 days’ pay.

Because Suffolk was the site of the shooting, Suffolk police were responsible first for determining whether a crime had been committed and, if so, by whom. After the district attorney’s office dropped all charges against Moroughan, Suffolk internal affairs examined the circumstances surrounding the cabdriver’s arrest.

Newsday’s look into how Long Island’s two county police forces have policed themselves uncovered the outcome of Suffolk’s internal investigation, including how ranking members of the department brought the case to a close under the near total secrecy that was imposed by law on police discipline.

From the editors

Long Island’s two major police departments are among the largest local law enforcement agencies in the United States. Protecting and serving, the Nassau and Suffolk county police departments are key to the quality of life on the Island — as well as the quality of justice. They have the dual missions of enforcing the law and of holding accountable those officers who engage in misconduct.

Each mission is essential.

Newsday today publishes the third in our series of case histories under the heading of Inside Internal Affairs. The stories are tied by a common thread: Cloaked in secrecy by law, the systems for policing the police in both counties imposed no, or little, penalties on officers in cases involving serious injuries or deaths.

This installment focuses on how the Suffolk County Police Department investigated the unjustified shooting in Suffolk of a cabdriver by an off-duty Nassau County Police Department officer in 2011.

SCPD officers wrongfully arrested the cabbie and chose not to investigate potential crimes by the shooter, who had been drinking. Later, a secret report obtained by Newsday shows that Suffolk brass pressed the department’s internal affairs commander to delete evidence that supported charging two sergeants with misconduct.

Newsday has long been committed to covering the Island’s police departments, from valor that is often taken for granted to faults that have been kept from view under a law that barred release of police disciplinary records.

In 2020, propelled by the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the New York legislature and former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo repealed the secrecy law, known as 50-a, and enacted provisions aimed at opening disciplinary files to public scrutiny.

Newsday then asked the Nassau and Suffolk departments to provide records ranging from information contained in databases that track citizen complaints to documents generated during internal investigations of selected high-profile cases. Newsday invoked the state’s Freedom of Information law as mandating release of the records.

The Nassau police department responded that the same statute still barred release of virtually all information. Suffolk’s department delayed responding to Newsday’ requests for documents and then asserted that the law required it to produce records only in cases where charges were substantiated against officers.

Hoping to establish that the new statute did, in fact, make police disciplinary broadly available to the public, Newsday filed court actions against both departments. A Nassau state Supreme Court justice last year upheld continued secrecy, as urged by Nassau’s department. Newsday is appealing. Its Suffolk lawsuit is pending.

Under the continuing confidentiality, reporters Paul LaRocco, Sandra Peddie and David M. Schwartz devoted 18 months to investigating the inner workings of the Nassau and Suffolk police department internal affairs bureaus.

Federal lawsuits waged by people who alleged police abuses proved to be a valuable starting point. These court actions required Nassau and Suffolk to produce documents rarely seen outside the two departments. In some of the suits, judges sealed the records; in others, the standard transparency of the courts made public thousands of pages drawn from the departments’ internal files.

The papers provided a guide toward confirming events and understanding why the counties had settled claims, sometimes for millions of dollars. Interviews with those who had been injured and loved ones of those who had been killed helped complete the forthcoming case histories and provided an unprecedented look Inside Internal Affairs.

Newsday found that:

- The Suffolk County Police Department ruled there was no misconduct by any member of the force and ordered no discipline.

- In finding no fault, then-Commissioner Edward Webber overruled the department’s internal affairs chief, who had called for filing misconduct charges against a sergeant and a detective sergeant.

- Former Chief of Detectives William Madigan pressed internal affairs commanding officer Michael Caldarelli to delete evidence from a report that Caldarelli considered crucial to supporting the charges, including accounts that DiLeonardo smelled of alcohol and that Moroughan had been given morphine, according to notes handwritten by Madigan.

- Madigan pushed Caldarelli to change his report at a meeting also attended by police Capt. Alexander Crawford, an attorney who is the department’s chief legal officer, who also had served as a trustee of the Superior Officers Association, the union representing the sergeant and detective sergeant.

- Caldarelli rebuffed Madigan and Crawford, notifying Webber in a memo that he refused to make the deletions they requested.

- The department permitted a second trustee of the Superior Officers Association, a sergeant, to play a key role in recommending whether or not to file charges against any officers involved in investigating the shooting at a time when the sergeant was both a union member and a union trustee.

Moroughan, then 26, had been shot twice and had his nose broken as DiLeonardo tried to rip him from the cab. Moroughan had spent the night at the hospital calling out repeatedly for his lawyer, he said, before Suffolk police arrested him. He faced seven years in prison on the charges that included assaulting an officer, which were later dropped.

At Newsday’s request, five experts in criminal law or police misconduct reviewed a detailed account of the case. Newsday based the account on internal affairs documents obtained from court files and confidential sources, official public statements and Caldarelli’s recollections of an internal affairs tenure that he described as “Kafkaesque.” The Suffolk police department denied a Newsday Freedom of Information Law request for internal affairs documents related to the case.

The experts who reviewed the case included a former 15-year Manhattan assistant district attorney who prosecuted homicides and violent street gangs; a former Manhattan and Bronx prosecutor who teaches at Pace University Law School and is author of “Prosecutorial Misconduct,” a treatise on wrongful convictions; a former police officer turned criminologist who has tracked the arrests of 20,000 police officers over the past 15 years while teaching at Bowling Green State University in Ohio; a former California Superior Court judge who conducted independent audits of police misconduct investigations; and a New York Law School professor who served as a law clerk to a federal appeals court and as an appellate lawyer for the Washington, D.C., public defender’s office.

Unanimously, the five experts concluded that based on the evidence provided by Newsday Moroughan had not committed a crime; that Suffolk police had wrongfully arrested him; that DiLeonardo had shot Moroughan without legal justification; and that Suffolk police could have arrested DiLeonardo.

Some also concluded that Suffolk police used Moroughan’s arrest to cover up DiLeonardo’s crime; that former Suffolk District Attorney Thomas Spota reinforced the apparent cover-up by declining to conduct a grand jury investigation; and that Suffolk police leadership completed the cover-up by overruling its internal affairs chief and taking no action against detectives and supervisors who participated in Moroughan’s arrest.

“It’s a cover-up of a cover-up,” said Bennett Gershman, the Pace University law professor, adding:

“They don’t want the truth to come out, because if the truth comes out, it’s very embarrassing. And maybe even worse, it’s criminal.”

‘It’s a cover-up of a cover-up.’

Bennett Gershman, Pace University criminal law professor and former prosecutorIn addition to potentially filing criminal charges against DiLeonardo for shooting Moroughan, Gershman said Suffolk law enforcement authorities had grounds for exploring whether other officers had committed crimes such as obstruction of justice or filing false documents.

Caldarelli led Suffolk’s Internal Affairs Bureau from late 2012 to 2014, when, he believes, he was forced out because he had recommended substantiating too many misconduct charges against officers. He retired from the department with the rank of inspector in 2017.

In a Newsday interview, Caldarelli recalled telling Webber: “It’s clear to me that there are people inside and outside of the department who seem to feel that internal affairs should be functioning as an organ of defense. I said it cannot be that way. By very definition that’s corruption, and I won’t be a party to it.”

His account of how the cabdriver’s shooting played out at the department’s highest levels bolstered a key conclusion of Newsday’s Inside Internal Affairs investigation: That the Nassau and Suffolk police departments have allowed officers to escape all, or most, discipline even in cases involving serious injuries or deaths.

What follows is a history of how Suffolk police wrongfully moved to jail the victim of a police shooting rather than potentially subject an officer to criminal prosecution — and faced no discipline.

Moroughan had started driving the cab on a 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. shift a week before the shooting. Previously, he had worked as a tow truck operator and had driven a taxi for another company. He was single, having ended a relationship, and was helping to support three children.

Riding in the cab’s front passenger seat, Moroughan’s girlfriend, Kristie Mondo, witnessed the gunfire that pierced the windshield and hit Moroughan in the chest and arm. He was held overnight in a hospital. When the wounds proved not to be life-threatening, Suffolk police transported Moroughan to the Second Precinct in Huntington, then walked him in front of the media with his hands cuffed behind his back, on his way to an arraignment in Central Islip court.

Later that day, Mondo secured bail and won Moroughan’s release from Riverhead jail. Charged with offenses that carried a maximum sentence of seven years, he retained a criminal lawyer and lived under the threat of conviction and imprisonment for three months before the district attorney’s office dropped the case.

Moroughan declined to be interviewed by Newsday on the advice of his attorney, Anthony Grandinette.

Webber, who retired as commissioner in 2015, did not respond to interview requests.

Former detective chief Madigan disputed that he and Crawford ordered Caldarelli to delete any material or to change his findings. Instead, he said that he only informed Caldarelli his conclusions were wrong.

“Us ordering him to remove anything, that’s blatantly false,” Madigan said.

DiLeonardo, through his attorney, Bruce Barket, declined to comment. Barket said DiLeonardo was justified in shooting Moroughan.

More than a decade later, Suffolk and Nassau counties are contesting a lawsuit in which Moroughan is seeking $30 million in damages. Suffolk has argued that its officers “acted reasonably and in good faith” and were justified in arresting Moroughan. Nassau has blamed Moroughan for allegedly causing DiLeonardo to shoot him.

‘Both counties were involved in a cover-up for the purpose of protecting their officers.’

LaDoris Cordell, former California judge and internal affairs auditor“This is all appalling,” said LaDoris Cordell, the retired California Superior Court judge, who reviewed internal affairs cases as San Jose’s independent police auditor from 2010 to 2015.

“I really do believe that law enforcement and prosecutors in both counties were involved in a cover-up for the purpose of protecting their officers from criminal and civil liability.”

Drinking, driving, shooting

DiLeonardo and his girlfriend joined fellow Nassau County Police Officer Edward Bienz and his wife for a Saturday night dinner at a Farmingdale restaurant on Feb. 26, 2011. DiLeonardo drank at least two cocktails, Bienz told investigators. Bienz had three beers.

They then drove to Huntington village, where they visited three bars. DiLeonardo drank five more vodka cocktails while Bienz drank five additional beers, Bienz reported. In his own statement to Nassau internal affairs, DiLeonardo put his alcohol consumption at six drinks during the night. A Suffolk district attorney’s investigator reported that DiLeonardo admitted consuming eight to 10 drinks.

The couples headed home around 1 a.m., with Bienz driving an Acura and DiLeonardo behind him in an Infiniti. On West Hills Road, the two cars came up behind Moroughan in his cab. Moroughan testified that Bienz passed, cutting him off. DiLeonardo followed, flashing his high beams and forcing Moroughan to the side of the road, Moroughan said.

WHERE IT HAPPENED

Continuing on their way, the off-duty officers made a wrong turn and pulled over. Moroughan, who had started driving again, encountered them. He stopped, rolled down a window and yelled at DiLeonardo about reckless driving. DiLeonardo shouted back with profanities and insulted Moroughan’s girlfriend, who was riding in the cab’s passenger seat, the cabdriver stated.

Moroughan got out of his car but retreated when DiLeonardo and Bienz got out of theirs.

Throwing the Prius into reverse, he backed up 30 to 45 feet. DiLeonardo followed on foot, at some point drawing a .38 caliber Smith & Wesson from an ankle holster. Moroughan put the Prius into drive and angled left to make a U-turn. He estimated that he moved a foot or two before DiLeonardo opened fire, emptying the five-shot revolver.

Two bullets hit Moroughan, one in the chest, one in an arm. DiLeonardo approached the cab, broke the driver’s window with his gun butt and pummeled Moroughan with it, breaking his nose.

With Moroughan “bleeding appreciably,” according to a crime scene analysis, DiLeonardo tried to drag Moroughan from the cab. During the struggle he dropped the revolver into the Prius, where it would later be recovered by Suffolk police.

Bienz ran toward DiLeonardo. Initially, he reported that he tried to help DiLeonardo make an arrest, indicating that he believed Moroughan may have committed a crime. Later, Bienz said that he only “intended to intervene between two individuals who were fighting over a loaded handgun.”

Attempting to escape, Moroughan put the Prius into reverse again. The moving car knocked down DiLeonardo and Bienz. Moroughan made a U-turn and drove to Huntington Hospital. His girlfriend dialed 911, reporting that a man in an orange shirt had shot her boyfriend and telling the operator, “I think that kid said that he was a cop.”

Near pooled blood on the roadway, Bienz yelled at DiLeonardo, “Dude, what the [expletive] did you just do?” he told internal affairs investigators.

No cause to fire, experts say

Under New York law, police and civilians alike may use deadly force in self-defense if they reasonably believe their lives are in danger.

DiLeonardo was acting as a civilian when he confronted Moroughan, according to legal experts. Moroughan had not committed a crime by shouting at DiLeonardo and then had tried to leave the confrontation by backing up. At that point, they said, DiLeonardo had no grounds to act against Moroughan as a police officer.

“I don’t see any cause for a private individual to take out a gun and threaten the other person with deadly force like that,” said Gershman, the Pace law professor. “I don’t see any justification for even removing his gun and displaying his weapon.”

Instead, Gershman said, DiLeonardo had a duty to retreat to safety from perceived danger rather than use deadly force.

New York Law School Professor Justin Murray said, “I see no evidence whatsoever that Moroughan engaged in any kind of criminal activity and no justification for the officer to resort to displaying a gun, much less firing at him.”

‘He should’ve been arrested that night.’

Philip Stinson, former police officer and Bowling Green State University criminal justice professorBowling Green Professor Philip Stinson said of DiLeonardo: “He should’ve been arrested that night.”

Stinson’s 20,000-case database breaks down arrests of police officers by location and types of offenses. When officers are implicated in crimes, investigators are often less aggressive than they are when looking into offenses committed by civilians.

“They start with a different set of assumptions,” Stinson said. “Evidence isn’t collected. Witnesses aren’t canvassed.”

No alcohol testing

DiLeonardo called 911. He reported that he was a Nassau County police officer, thought he had been shot and issued a code for a cop in distress. More than 20 officers swarmed the scene. Accounts given to internal affairs investigators and in Moroughan’s lawsuit described what then happened.

Sgt. Jack Smithers, the top responding officer, reported that DiLeonardo was teary-eyed, said that he couldn’t find his gun and again said that he thought he had been shot. He was bleeding from what turned out to be a cut finger. Another officer described Bienz as “shaken up.”

Initially, investigators from Suffolk’s Second Precinct in Huntington viewed Moroughan as a possible victim and DiLeonardo as a possible suspect. Det. Patricia Niemir ordered the crime scene labeled as the setting for investigating a first-degree assault: a shooting.

She was introduced there both to Nassau County Police Department Deputy Chief John Hunter, who was heading up a team responsible for scrutinizing the shooting, and to Nassau County Police Department PBA President James Carver. Niemir reported to internal affairs that she did not discuss the investigation with them and didn’t work on it long enough to determine who had committed a crime and who was a victim.

Two residents of nearby homes called 911 after the shooting. One of them had been an eyewitness. Still, a Suffolk County detective reported that a neighborhood canvass proved unsuccessful.

Interviewed months later by Nassau County internal affairs — rather than by one of the Suffolk officers who was at the scene of the shooting — the witness reported that he had seen “a man with a gun walking towards a white car which was stopped in the middle of the road. The man with the gun was shooting his gun at the windshield of the car.”

The man with the gun was shooting his gun at the windshield of the car.

Internal affairs witness statement

In New York City, New York Police Department regulations mandate that a police officer who discharges a firearm must take a Breathalyzer test, regardless of whether on duty or off duty. When readings are above .08, the legal limit for driving while intoxicated, supervisors must order further alcohol testing, can command officers to surrender firearms and must notify internal affairs.

The Suffolk department does not conduct mandatory alcohol or drug testing of officers after shootings. Spokeswoman Dawn Schob said the county’s police contract permits testing only when fellow officers suspect that a shooter is impaired.

An officer and a detective separately detected the smell of alcohol around DiLeonardo, Bienz and their companions. They told internal affairs that they hadn’t been able to tell who was emitting the odor.

Smithers, the sergeant on scene, spoke with DiLeonardo. In a deposition, he quoted DiLeonardo as asking, “Sarge, can you help me?”

He told internal affairs that he saw no evidence that DiLeonardo was intoxicated and reported that he didn’t question DiLeonardo about alcohol consumption.

“It wasn’t even a thought in my eyes. I didn’t smell it,” Smithers told internal affairs.

Suffolk police ordered no sobriety testing

Murray, the New York Law School professor, called the failure to investigate alcohol consumption by DiLeonardo and Bienz “a really inexcusable oversight.”

Measuring DiLeonardo’s sobriety was crucial to determining whether he reasonably believed that he faced a threat when Moroughan drove the cab forward.

“The odds he’s acting reasonably plummets precipitously if it turns out he’s not in his right mind because of intoxication,” Murray said.

Detectives take a contested statement

An ambulance took DiLeonardo and Bienz to Huntington Hospital.

More than 30 officers, detectives and police supervisors crowded the emergency room. They came both from Suffolk, whose department was responsible for investigating the shooting, and from Nassau, home base of DiLeonardo and Bienz. The personnel included four representatives of the two officers’ union, the Nassau Police Benevolent Association, and a PBA attorney.

An emergency room physician recorded that DiLeonardo was “slurring words at times with smell of alcohol on breath.”

Noting that he was also sweating and had bloodshot eyes, the doctor described DiLeonardo as “hostile,” found his “psychiatric insight and judgment to be impaired” and wrote that DiLeonardo refused to undergo blood or urine testing aimed at pinpointing his level of intoxication.

A Suffolk detective wrote that the doctor remarked: “Great, you can get drunk, shoot someone and walk out the same day.”

Within a few hours, the department gave the case to homicide detectives, who investigate officer-involved shootings. They focused on Moroughan as a suspect rather than on a possible first-degree assault by DiLeonardo.

After Moroughan’s wounds proved not to be life-threatening, he was placed in a room under police guard. He testified in a lawsuit deposition that the officer asked what happened and he answered, “I got into an argument on the road and this [expletive] psycho jumped out of his car and started shooting at me for no reason.”

He told a doctor that he thought he was “going to die” when the “guy got out of the car with a gun,” and he testified in a preliminary lawsuit hearing that police rebuffed repeated requests for a lawyer.

Moroughan’s godmother, Risco Mention-Lewis, arrived at the hospital. She then served as a Nassau County assistant district attorney and is now a Suffolk police department deputy commissioner. Police refused her entry to Moroughan’s room.

Over the course of the night, his regimen of drugs included the sedative Ativan and the narcotic painkillers morphine, Dilaudid and Percocet.

Homicide detectives Ronald Tavares and Charles Leser arrived around 4 a.m. Interviewed six hours later at the precinct, DiLeonardo and Bienz told the detectives they each had consumed only a couple of drinks.

The detectives took statements from DiLeonardo, his girlfriend, Bienz’s wife and Moroughan’s girlfriend. The detectives did not take a statement from Bienz. Their supervisor, Det. Sgt. William Lamb, told internal affairs that he never ordered the detectives to get Bienz’s account of what happened in writing.

Two former prosecutors said detectives should have taken a statement from Bienz.

Calling a written witness statement “the best evidence you have of what happened,” Gershman, the Pace University law professor, said: “It’s hard to believe they wouldn’t take a statement from every witness at the scene of the incident. That’s suspicious.”

Ayanna Sorett, a fellow at Columbia University’s Center for Justice who served for 15 years as an assistant Manhattan district attorney, wrote in an email that investigations of possible criminal conduct by police are among the most challenging for prosecutors.

“Obtaining detailed facts at the very beginning is imperative as it lays the groundwork for a thorough and effective investigation,” she wrote, also citing a need to gather statements from witnesses “when the information is fresh in their mind” and “before these witnesses can be influenced by others.”

Around 5:50 a.m., Lamb ordered Tavares and Leser to question Moroughan. An hour later, Tavares wrote out a statement that purported to be Moroughan’s account of his encounter with DiLeonardo. Leser witnessed the document.

It quoted Moroughan as saying that he had been angry about traffic from the start of his shift, that he got angrier in the confrontation with DiLeonardo, and that he had aimed his car at DiLeonardo.

Implicating himself in a crime, Moroughan reportedly said: “I revved my engine. I drove forward toward the guy who was standing in the street near his white car.”

He also allegedly said that he believed DiLeonardo shot in self-defense — in effect, establishing that DiLeonardo was legally justified to open fire.

“I felt he fired at me to protect himself because I drove at him,” the detective quoted Moroughan as saying.

I felt he fired at me to protect himself because I drove at him.

Disputed statement allegedly made by Thomas Moroughan

Gershman said Moroughan’s statement was exactly what police needed to justify DiLeonardo’s shooting, exonerating the officer and implicating Moroughan.

“If it was a script, it was a good script,” he said.

Grandinette, the lawyer representing Moroughan in the $30 million lawsuit, said Tavares and Leser constructed the statement with the language necessary to frame Moroughan and spare DiLeonardo.

“The Suffolk County Homicide Bureau, and all the officers who were at the hospital that were involved in this case, knew that there was only one out for DiLeonardo and Bienz. And that singular out is to claim justification. And, so, they create and fabricate these statements” Grandinette said, adding:

“The outrageous thing is that these detectives were willing to frame an innocent man, for serious criminal charges that would send him to prison, in order to shield Anthony DiLeonardo and Edward Bienz from administrative and criminal sanctions.”

Leser, who retired in 2020, didn’t return calls for comment. A department spokeswoman said Tavares would not comment because of litigation.

Lamb arrested Moroughan on a charge of second-degree assault. He alleged that Moroughan had injured DiLeonardo with the intent of preventing a police officer from making an arrest. Lamb also alleged that Moroughan had recklessly endangered DiLeonardo by accelerating the car toward him.

Initial probe backs shooter

Less than 12 hours after the shooting, four high-ranking Nassau County officers completed a preliminary investigation that became the first to clear DiLeonardo and Bienz of wrongdoing.

After shootings, members of the county’s Deadly Force Response Team render initial judgments about whether officers acted properly in discharging their weapons.

Based on the investigation conducted by Suffolk officers and its own evaluation of the scene, the team concluded that DiLeonardo had acted within guidelines when he shot Moroughan.

Their report cited as fact that Moroughan “began to drive his vehicle directly at DiLeonardo.” It did not mention alcohol consumption.

The team judged DiLeonardo and Bienz to be “fit for duty.” They returned to work after sick leaves — 12 days for DiLeonardo, 10 days for Bienz — related to injuries sustained in the incident.

When Moroughan’s criminal defense attorney called for the release of records that would show DiLeonardo and Bienz had been drinking, the Nassau police union backed DiLeonardo.

“Any allegation of any alcohol is intended as a distraction from the defendant’s actions,” PBA President Carver told Newsday at the time.

Crime lab analysis undermines charges

The Suffolk County Crime Laboratory dispatched an investigator to the site of the shooting. Working independently from police and prosecutors, the lab analyzes evidence ranging from DNA samples to the length of tire tracks left after a fatal car collision. Its responsibilities also include analyzing and reconstructing crime scenes.

After studying the events, including the kind of car Moroughan was driving, the locations of the cars and DiLeonardo’s use of an ankle holster, lab analyst George Krivosta reported that DiLeonardo “follow[ed] on foot” when Moroughan climbed back into his taxi after the shouting match.

Where DiLeonardo and the Deadly Force Response Team described Moroughan as “revving” his Prius engine before driving at DiLeonardo, Krivosta wrote that the hybrid’s motor system was quiet.

He also doubted that DiLeonardo had time to reach and draw the revolver from his ankle in a split-second reaction to an oncoming vehicle, as DiLeonardo had stated.

“The difficulty of drawing a weapon from an ankle holster would have required him to have drawn the weapon prior to” the car’s movement, Krivosta wrote, also stating that DiLeonardo “may have been concealing the weapon from view by holding it at his side.”

More than three months after Moroughan’s arrest, the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office asked a judge to dismiss the case.

In court, Assistant District Attorney Raphael Pearl said there was a “significant deficiency in the proof” against Moroughan and cited evidence both that Moroughan had withdrawn from the confrontation and that DiLeonardo had been drinking.

Sergeant on DiLeonardo drinking:

It wasn’t even a thought in my eyes. I didn’t smell it.

Source: Suffolk internal affairs report

slurring words at times with smell of alcohol on breath.

Source: Nassau internal affairs report

Pearl also noted that Moroughan had suffered two gunshot wounds and a broken nose while DiLeonardo’s most serious injury was a cut finger.

The judge dismissed the charges, clearing Moroughan.

District attorney decides no grand jury investigation

With the evidence indicating that DiLeonardo had shot and wounded Moroughan without cause while under the influence of alcohol, Suffolk DA Spota had the power to pursue an assault charge before a grand jury.

Instead, Spota chose to drop the matter.

Moroughan’s defense attorney, William Petrillo, told the judge that he had advised Moroughan “that there is no need to be testifying before a grand jury or participating in any criminal proceedings.”

Outside court, a spokesman for the DA said the office would not seek charges against DiLeonardo because Moroughan preferred not to testify.

“I’m glad I can move on with my life. It’s just nice to know I don’t have to worry,” Moroughan said.