In spring 2001, Northrop Grumman was in the midst of selling off most of the 600-acre Bethpage home of Grumman Aerospace, the defense giant it gobbled up a few years before.

As workers conducted routine soil tests, they made a discovery that jolted the company and the community.

They found the toxic industrial compound polychlorinated biphenyl, or PCB, on the site’s far eastern boundary. While such chemicals had long been identified in the heart of Grumman’s plant, this was on the fringe of Bethpage Community Park, a buzzing core of local activity built on land Grumman had donated to the Town of Oyster Bay four decades prior.

“Implications of PCB contamination within the park itself are enormous,” Northrop Grumman said in a May 2001 internal presentation.

The company was not overestimating matters.

On May 2, 2002, the town padlocked the 18-acre park after confirming that PCBs and various metals, including chromium, were present in the soil.

Its former ballfield, where generations of Bethpage children played, had been Grumman’s literal dumping ground, once described by the company as an “open pit” for its wastewater sludges and solvent-soaked rags.

The field remains closed today, a 3.5-acre scar in the middle of the community, still too filled with dangerous chemicals to use.

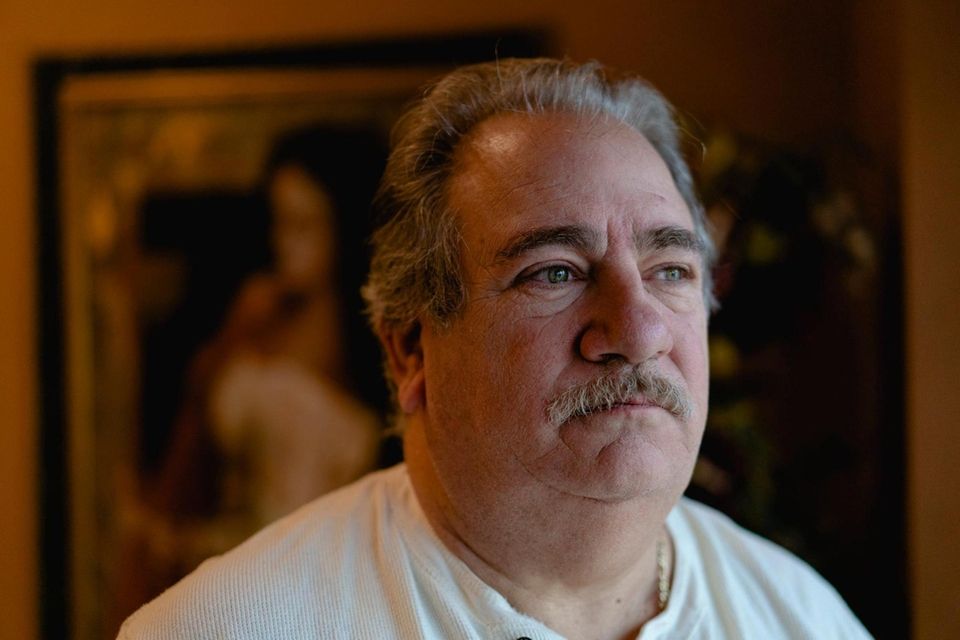

“No other town has something like that,” said John Coumatos, a local restaurant owner and Bethpage Water District commissioner. Of Grumman, he remarked: “They won a war — they won two wars, and we’re stuck with what’s left over. It’s not fair to us.”

From the moment the town shut the park — with then-Supervisor John Venditto saying, “Would I want one of my children sliding into home plate?” — the people of Bethpage have taken on the massive pollution problem with a new combativeness.

Nearly 900 people jammed the local middle school for the first public meeting after the closure. Some asked for their children to receive blood tests.

Years of public outcry, lawsuits and aggressiveness by local politicians followed until the state last year approved a $585 million plan for all but eliminating what has become Long Island’s greatest environmental crisis.

The plan is a sea change from past efforts by the state Department of Environmental Conservation, which had misjudged and failed to halt the spread of the groundwater pollution, all while relying heavily on flawed analyses provided by Grumman and its successor company, Northrop Grumman.

“The ballfield — the Bethpage Community Park — I think just kind of woke everybody up,” said Stephen Campagne, 65, a retired Con Edison worker who has lived in Bethpage for 40 years.

Stephen Campagne in his sister’s Bethpage home in February. Photo credit: Johnny Milano

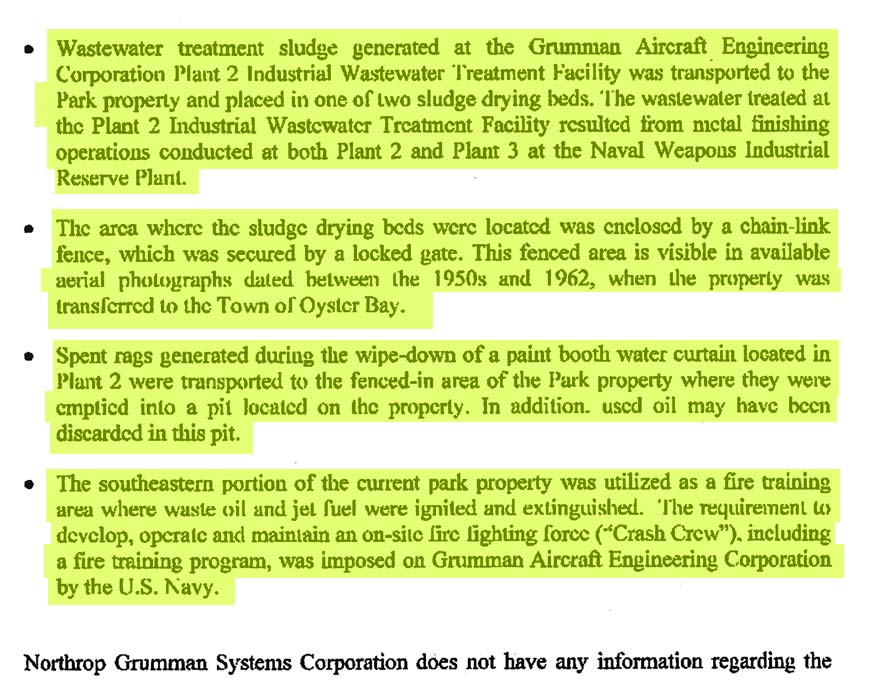

A year after discovery of the park contamination, a report by a Northrop Grumman consultant, Dvirka and Bartilucci, laid out the full extent of the toxic dumping there. It found that wastewater sludge “was transported to the park property and placed in one of two sludge drying beds”; that “spent rags generated during the wipe-down of a paint booth water curtain” were “emptied into a pit located on the property”; and that the land was “utilized as a fire training area where waste oil and jet fuel were ignited and extinguished.”

And the soil contamination all that caused wasn’t the worst of it.

In 2007, Bethpage Water District consultants were reviewing data from a U.S. Navy monitoring well just south of the park. They found the carcinogenic metal degreasing solvent trichloroethylene, or TCE, in the groundwater at 6,300 parts per billion — more than a thousand times higher than the state limit for drinking water and far more than its closest treatment system could handle.

The state identified this in 2009 as emanating from the ballfield, a clear indication the park was the source of a second plume, deeper and more contaminated than the well-established one that had poured out from Grumman’s old manufacturing grounds.

For Bethpage and the communities to the south, the discovery was deeply distressing. It meant a still greater spread of groundwater contaminants and more concerns about the possible health effects, despite local water providers’ assurances that they remove anything dangerous from what’s delivered to taps.

For Northrop Grumman the concern grew, too. Under the state Superfund law governing hazardous waste sites, the company’s responsibility rose from simply cleaning the park’s soil to treating an even larger and still spreading mass of carcinogens.

The divisions between the community and the polluters also widened. As far back as 1976, the Nassau County Health Department and Grumman’s own consultants had identified troubling deposits of TCE on company grounds. And by 1989, Grumman had begun a substantial effort to extract the contaminants .

But during all those years of growing concerns, no records were found in which any Grumman or government official seemed to ask, in a meaningful way, “What about the park?”

The Newsday investigation identified only two instances, both in the 1990s, in which anyone had tested Bethpage Community Park. Those, by the Navy and town, literally went little beyond scratching the surface.

‘May continue to dump’

Part of the 18 acres of undeveloped land at Grumman’s northeast corner by the late 1940s became, in the words of an employee at the time, a “remotely located open pit” to dump its various wastes.

Aerial photographs from this era show the dirt from this portion becoming progressively darker and, as the company later put it, more “disturbed.”

This use wasn’t against the law, and none of it seemed to be of concern at the dawn of the 1960s, when the Town of Oyster Bay sought land in Bethpage for a new park. So in October 1962,Grumman gifted the parcel to the town for a community gathering spot that would include a playground, swimming pool and ballfields.

When the park opened two years later, Grumman insisted on a commemoration plaque, which still is displayed next to the swimming pool.

A dedication plaque at Bethpage Community Park memorializes that the property was donated by Grumman. Photo credit: Newsday / Steve Pfost

Weeds grow behind the fence closing off the abandoned ballfield at the park. Photo credit: Newsday / Steve Pfost

“This appears to be a suitable site,” town Supervisor John J. Burns had told Newsday in December 1961, when the donation was first proposed. In a photograph that memorialized the land transfer months later, the supervisor smiles alongside Grumman’s then-president.

By the time the deal closed , Burns knew more about the land than he had indicated.

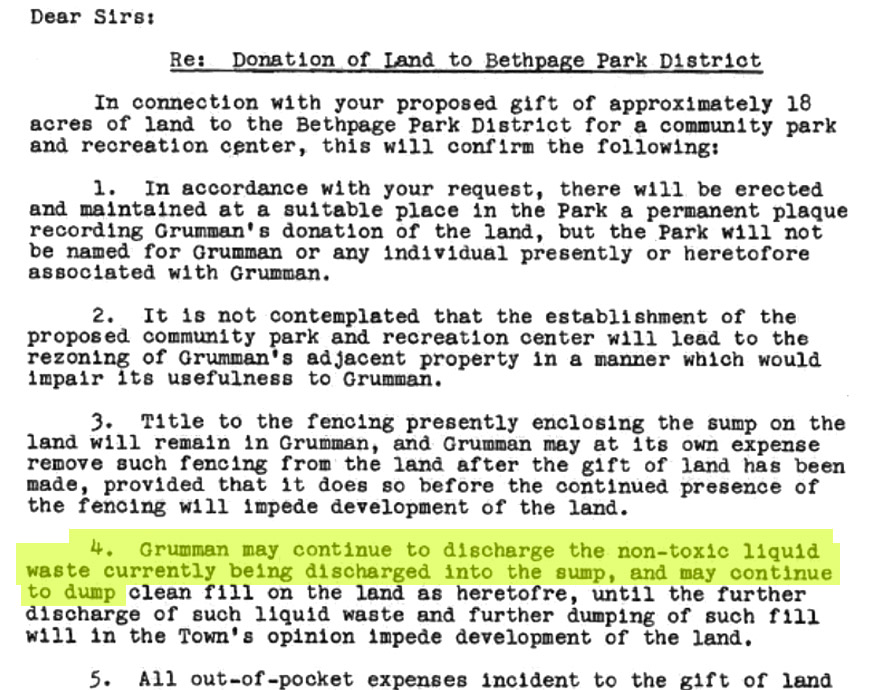

“Grumman may continue to discharge the non-toxic liquid waste currently being discharged into the sump, and may continue to dump clean fill on the land as heretofre [sic], until the further discharge of such liquid waste and further dumping of such fill will in the Town’s opinion impede development of the land,” Burns wrote in a 1962 letter to Grumman, obtained under a state Freedom of Information Law request and revealed for the first time.

The “non-toxic” reference indicates that the town was unaware that the waste posed any danger. Grumman, by available indications, could well have known otherwise.

“Grumman may continue to discharge the non-toxic liquid waste currently being discharged into the sump ….”

1962 letter from Town of Oyster Bay to Grumman See full letterNassau County in 1955 had alleged, in state filings related to Grumman’s application for new water wells, that even after the company treated wastewater dried on the future park property, it still contained the toxic metal chromium in levels that could contaminate the water supply.

In 2013, Northrop Grumman environmental consultants confirmed that the wastewater sludge dumped at the park also contained TCE, a volatile organic compound, or VOC, that wasn’t viewed as a danger in the early 1960s but is now the plume’s most prevalent contaminant.

“Whatever was disposed in the rag pit has contributed to VOCs to groundwater,” Michael Wolfert, a project director at the consulting firm, Arcadis Inc., said in a deposition taken in a federal lawsuit by Grumman’s former insurers.

The insurers, including the Travelers Cos., successfully argued that Grumman didn’t provide full or timely notice of potential claims it could face from its environmental practices.

Shifting blame

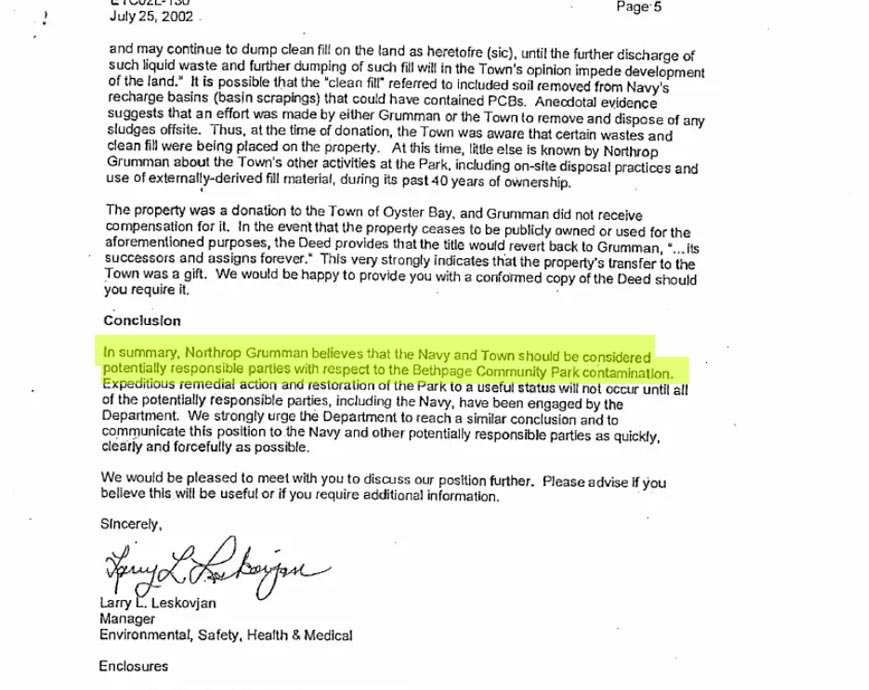

After the park was shuttered in 2002, Northrop Grumman expressed a willingness to work with the state on determining the extent of the soil contamination. But it also set off on a lengthy effort to limit its culpability and costs.

Its first line of attack was to try to shift cleanup responsibility to Oyster Bay and the Navy, which owned a portion of Grumman’s manufacturing facility that the company operated.

In letters to the state during the summer of 2002, Larry Leskovjan, then manager of environmental, health and safety for the company, acknowledged that Grumman engaged in “the drying of metal-bearing sludges” at the future park site. Yet he argued that “the contaminants at issue related directly to Navy Industrial reserve programs and military manufacturing dictated by the government.”

The Navy, he added, conducted annual inspections of Grumman’s facility and therefore “gave at least tacit” approval of the company’s disposal practices.

In written responses to Northrop Grumman, the Navy said there was “little to no relevant evidence” to back up those assertions.

And because Burns’ 1962 letter indicated that Grumman could continue some dumping at the site, Leskovjan wrote, “the town was aware that certain wastes and clean fill were being placed on the property.” He also suggested that Oyster Bay could have brought in its own contaminated fill after receiving the land.

The company later acknowledged it had no proof of the last point, though some coolant later leaked from the park’s old ice-skating rink, which the town is responsible for cleaning up.

“In summary, Northrop Grumman believes that the Navy and Town should be considered potentially responsible parties with respect to the Bethpage Community Park contamination.”

2002 letter from Northrop Grumman to state DEC See full letterThree years after Northrop Grumman first attempted to shift blame , Oyster Bay sued the company and the Navy over the contamination.

At the same time, the town worked with the state to expedite the cleanup of a seven-acre portion of the park, farthest from the ballfields, where it built a new ice-skating rink.

Aware of residents’ concerns, the town pressed for “mass” soil excavation of up to 10 feet, which it deemed necessary for long-term safety and the possibility of future uses, including residential. The state — which for years had endorsed overall cleanup measures often criticized as too limited — recommended a more targeted plan, costing $6 million, that would have left most soil in place. This, it concluded, would be “fully protective of human health and cost-effective.”

The town’s plan cost nearly four times as much, or $22 million. Defending itself in the town’s lawsuit, Northrop Grumman pointed to this battle between Oyster Bay and the state, asking for a judgment that it wouldn’t have to cover the town’s cleanup portion because it was excessive.

It dismissed the town’s argument about potential future uses by noting that the park’s deed stated the land would revert to Grumman if it ceased being publicly owned.

In May 2009, then-U.S. District Court Judge Thomas C. Platt granted the company’s request, ruling that the town’s plan was “plainly excessive.”

The judge did not order the company to cover the $6 million cost of the lesser plan, and Oyster Bay spokesman Brian Nevin told Newsday last month that Northrop Grumman has never offered to pay for it.

Breaking point

As Oyster Bay was fighting Northrop Grumman on one front, Anthony Sabino, the longtime lawyer for the Bethpage Water District, was engaging the company on another.

By 2009, the new park contamination led the water district to conclude that the treatment system on one of its drinking water wells, funded by Grumman in the early 1990s, was no longer sufficient. It wanted Northrop Grumman to pay millions of dollars for an upgrade.

The company didn’t share the district’s concern. In a series of letters, it cited its own projections of the plume’s movement and argued that it did not pose an imminent threat to the district wells.

“In fact, Northrop Grumman’s consultants cannot identify what facts form the basis of the Water District’s claim that there is now an emergency situation,” a company lawyer wrote to the district.

Negotiations hadn’t gotten anywhere by 2010 when Sabino took his case to Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.). Northrop Grumman, he wrote, “steadfastly refuses to be responsible for these necessary improvements based on a groundwater model that has consistently, without exception, underestimated the direction, depth, concentration of plume contaminants and the plume’s impact on down gradient water suppliers.”

He continued: “This perfect record of failure can not [sic] be coincidence,” labeling the company’s computer modeling of the plume “liability driven,” with the goal “of shifting liability from the responsible parties to the residents of Bethpage.”

Anthony Sabino, attorney for the Bethpage Water District, speaks before a packed house at Bethpage High School during a June 2012 meeting about groundwater at the Community Park. Photo credit: Daniel Goodrich

Northrop Grumman, meanwhile, sought to discredit other information — including its own — that could increase its liability.

Back in 2003, the Northrop Grumman consultant Dvirka and Bartilucci had provided its vivid description of how the Bethpage Community Park ballfield came to be so polluted, pointing to the wastewater sludge placed in drying beds, the “spent rags” “emptied into a pit” and the fire training area there.

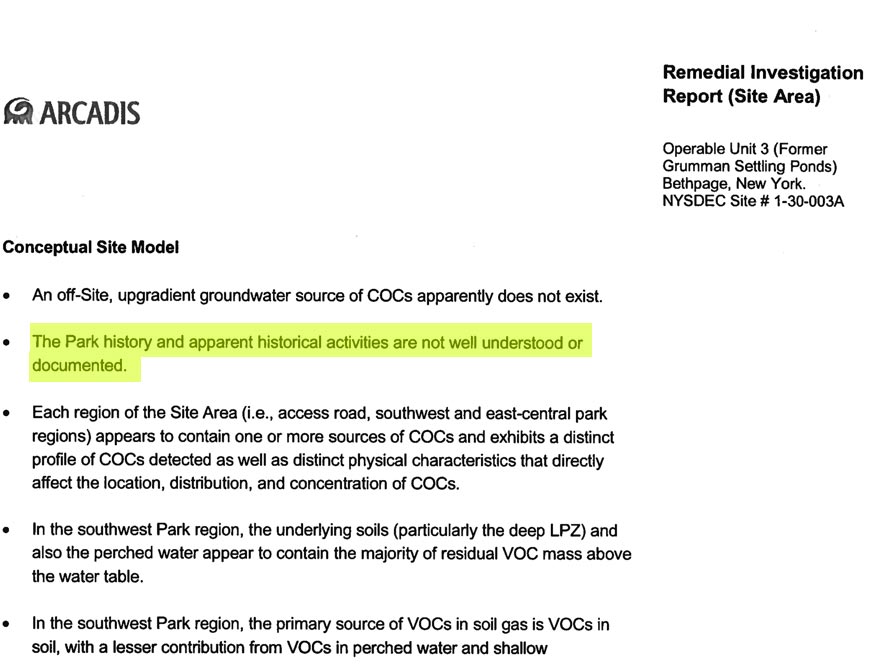

After discovery of the park plume, a second company consultant, Arcadis Inc., knocked down those findings.

“Apparent historical activities were not well understood or documented,” the firm wrote as it developed the groundwater cleanup plan for the park, adding that the previous consultants’ history was “speculation.”

Steven Scharf, a state environmental project engineer, replied: “This is not the case at all. Grumman clearly presented information to the contrary in [a] previously submitted report.” He demanded that the company reflect the 2003 history in its new material.

“The Bethpage Community Park … and the surrounding areas, are well understood,” Scharf continued, adding that “historic use(s) of the Park property are well documented.”

“The Park history and apparent historical activities are not well understood or documented.”

2011 report from Northrop Grumman consultant on Bethpage Community Park contamination, including a line first sent to regulators in 2008 See full page

“Wastewater treatment sludge … was transported to the Park property ….”

2003 report from Northrop Grumman consultant on Bethpage Community Park contamination See full pageWolfert, one of the Arcadis employees responsible for the revision, said in his 2013 deposition in the Travelers insurance case that Northrop Grumman had directed him to make the change because the 2003 account had relied on anecdotal recollections from employees at the time.

“They therefore wanted to modify the site history to not look like it was so definitively known,” Wolfert said in the deposition, adding later that the company did not require him to do any further investigation of the site history.

Plume model assailed

Most critical in the state’s decisions on how to attack the plume was a computer model developed by the company’s longtime consultant, Geraghty and Miller, later absorbed by Arcadis.

It would finally be discredited when Schumer and local water providers in 2010 prevailed upon the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Geological Survey to launch a review.

The tensions between Schumer and the state were palpable at the time, observers remember.

Judith Enck, the EPA’s then-regional administrator, recalled attending a September 2010 meeting on the plume organized by Schumer, and being pulled aside by a Long Island-based state environmental official.

“‘They’re getting pushed around by the Navy and Grumman,’” she recalled the person telling her of department leadership in Albany. “The state doesn’t seem capable of standing up to the Navy and Grumman.”

Bethpage Water District Superintendent Michael Boufis, left, gives a tour of Bethpage Water District’s Plant 6 to Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), center, and then-Navy Secretary Richard Spencer in September 2017. Photo credit: Newsday / Alejandra Villa

Enck said she had the same impression attending the meeting. “Usually, when you have Senator Schumer banging on the table, people are responsive,” she said recently. “The state took it as a state site and did not want any federal oversight.”

In a recent interview, Pete Grannis, the state environmental conservation commissioner from 2007 to 2010, maintained that his staff was not being run over by the polluters. Rather, he said, they were grappling with what had also confounded numerous past administrations. (The prior environmental commissioners could not be reached or did not return requests for comment.)

“This is something that at the time was thought to be somewhat of an intractable problem that sort of defied a solution that we could do and afford,” Grannis said. “We had serious questions about whether it could be contained and, if not, then what could be done to protect the drinking water as this moved.

“We didn’t have a very clear picture of what we could do about it.”

Federal environmental officials’ review of the long-standing plume model was pivotal.

In a 2010 memo, the EPA concluded it should “not be used to attempt to make a reliable prediction of potential impacts on public supply wells.”

Citing several inaccurate predictions, the agency, along with the geological survey, determined in a final 2011 report that the model simulated future movement in an “incomplete” manner and “ignores information” such as the impacts of public supply groundwater pumping and discharges from treatment systems.

“That was a big turning point,” said Carey, the Massapequa Water superintendent. “It ratcheted things up to say, ‘Hey, look, we have the federal government saying now that the model that you used was flawed and that we really need to start this over and look to take a new look.”

Another limited step

A change in approach from the state wasn’t immediate.

Its 2013 plan to address the park contamination proposed spending more than $60 million beyond the cost of earlier state cleanup decisions, which had covered soil contamination on the Grumman site and the original groundwater plume spilling out of that property. But the new plan didn’t go as far as local water providers sought.

It included cleaning the park’s ballfield of contaminated soil — a project that still hasn’t been completed.

It also called for cleanup of contaminated soil in residential yards next to a former Grumman access road. The state had found PCB contamination up to 58 times current state standards in 2002. By 2016, Northrop Grumman had removed soil contaminated with PCBs and chromium from the yards of 30 homes.

When it came to groundwater, the 2013 plan required Northrop Grumman to continue running a contaminant extraction system at the boundary of the park — similar to the one it has operated at its original plant boundaries — to stop further migration. Since 2009, that has pumped 300,000 gallons a day of tainted water and removed 2,200 pounds of toxic chemicals, the state estimates.

The plan called, too, for new off-site extraction systems at “hot spots” of high contamination south of the park, including one that Grumman finally hopes to complete in 2021. It will be the company’s first comprehensive remedial effort outside of properties it once owned.

But, as with prior cleanup decisions, the state chose not to endorse full plume containment , which would have cost more than $200 million and have involved an extensive series of extraction wells and piping.

Residents and local officials express frustration with the cleanup at a November 2019 public meeting in Bethpage. Photo credit: Yeong-Ung Yang

“It’s the best alternative that we can come up with,” a state public health specialist, Steven Karpinski, said at a public hearing where the plan was criticized by residents and elected officials.

Northrop Grumman endorsed the state’s approach in a public comment included in the plan document: “The NYSDEC groundwater remedy is appropriate with some minor modifications.”

By this point, however, public knowledge, concern and outrage were erupting.

The new state effort got far more media attention than any prior ones, and the Bethpage Water District was becoming more vocal in airing its grievances, including the discovery of elevated radium levels in one of its wells.

At the same time, a state study of cancer in part of Bethpage — finding no higher overall rates — was released nearly four years after toxic soil vapors had been found near some homes.

In a 2013 email to state environmental officials, Bethpage resident Rosalie Romano asked, “Why has the NYS DEC not been acting in the best interests of the residents of Bethpage?”

George Hignell, another longtime Bethpage resident, wrote to then-Nassau District Attorney Kathleen Rice in a pleading email that asked her to investigate why the problem had been obscured. He cited the deaths of his parents and numerous neighbors to cancer and compared the growing groundwater contamination to one of the nation’s most infamous cases of industrial pollution.

“We are the new ‘Love Canal,’” Hignell wrote, referencing the massive contamination and evacuation of a community near Buffalo. “We need you to help us. Please.”

Aides to Rice, now a congresswoman, said there’s no record of her office opening an investigation.

‘Master of delay’

As the pressure was rising for something more to be done, Northrop Grumman was still fighting calls for it to do — and pay— more. Nowhere was this more visible than in another courtroom skirmish, this time with the Bethpage Water District.

The district wanted nearly $10 million to protect the public well it identified as being threatened by contamination from the park plume. It had discovered the park contamination six years before, in 2007, and started negotiating in earnest in 2009.

Early on, Sabino recalled feeling the strong implication from Northrop Grumman, passed along from elected officials in the area, that the company would relocate its 2,500 employees still based in Bethpage and blame the district if it continued to push for compensation.

At the peak of the recession, few wanted to call the company’s bluff.

“We should have hit them hard when we had the chance,” said John Sullivan, a district water commissioner. “But we would have taken the brunt of it.”

The district finally filed a lawsuit in 2013. Sabino was feeling confident, even though the district had 12 full-time employees and a budget of a few million dollars a year and was going up against a multinational corporation with almost $25 billion in revenue and 85,000 employees.

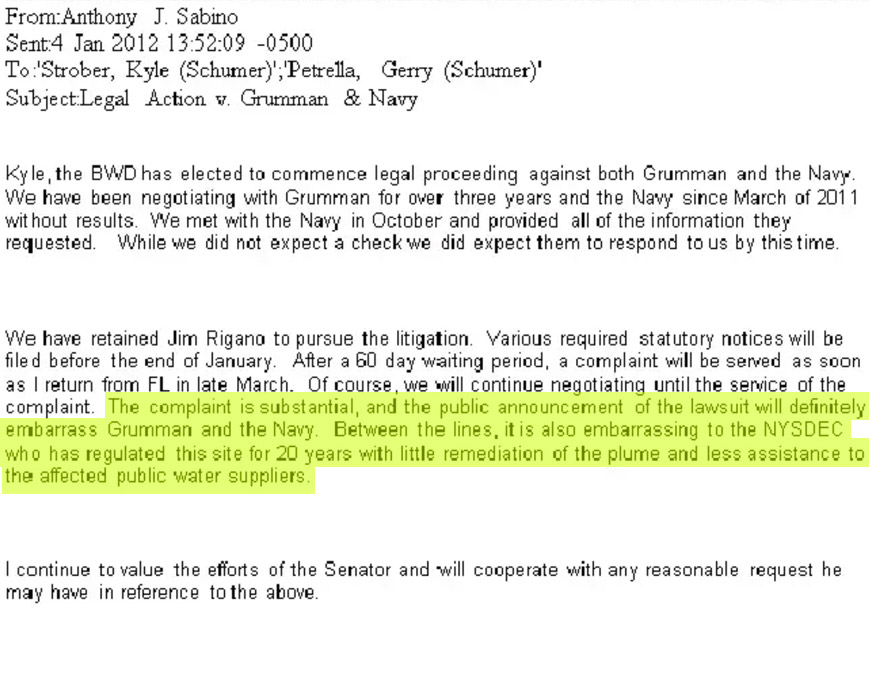

Well before the suit was filed, he wrote in an email to Schumer’s office: “The complaint is substantial, and the public announcement of the lawsuit will definitely embarrass Grumman and the Navy. Between the lines, it is also embarrassing to the NYSDEC who has regulated this site for 20 years with little remediation of the plume and less assistance to the affected water suppliers.”

“The complaint is substantial, and the public announcement of the lawsuit will definitely embarrass Grumman and the Navy. Between the lines, it is also embarrassing to the NYSDEC who has regulated this site for 20 years with little remediation of the plume and less assistance to the affected public water suppliers.”

2012 email from Bethpage Water District attorney to Sen. Chuck Schumer’s office See full emailThe time spent in negotiations, however, proved fatal to the district’s case.

Northrop Grumman argued that officials had three years from the discovery of the park plume to file a claim. A judge agreed, and the district’s ratepayers footed the bill for the upgraded well treatment.

“They are the master of delay,” district superintendent Michael Boufis reflected recently, as he reached for a David vs. Goliath analogy. “This is biblical, what’s going on here.”

To the south, Massapequa Water District has been watching.

Stan Carey, the district superintendent, said it has resisted putting the same expensive contaminant treatment systems on its wells while pushing the state to contain the plume. But estimates have the mass reaching Massapequa’s early detection wells in as little as two years.

“At some point you have to start pulling it out of the ground and cleaning it up,” Carey said.

‘I said ‘no’

In 2014, Joseph Saladino, then Massapequa’s Republican assemblyman, convinced the Democratic-led Assembly to pass his long-stalled bill authorizing a feasibility study for a system of hydraulic wells that would fully contain the plume at its southern edge. It was similar to proposals the state, Northrop Grumman and the Navy for years had called too costly and unworkable.

But with increased pressure from residents — and against the backdrop of the drinking water crisis in Flint, Michigan — the political climate had turned.

The Senate passed the law in June 2014. Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo signed it into law in the last days of the year, overriding concerns by his former environmental leadership.

Saladino, now Oyster Bay town supervisor, recalled seeing Cuomo at the wake of his father, former Gov. Mario Cuomo, in January 2015, where the governor told him, “You know, they told me to veto your bill. And I said ‘no.’”

That decision set off a new era of action by the state. Cuomo named Basil Seggos, a longtime environmentalist who had served in Cuomo’s office, the department’s commissioner and committed to a tougher approach later in 2015.

Basil Seggos, commissioner of New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, says the state will fight to push through its $585 million cleanup plan. Photo credit: James Carbone

In a recent interview, Seggos reflected on the longtime stances of Northrop Grumman and the Navy. “They tend to get into cruise control unless poked and prodded,” he said. “I believe that’s where they were.

“In the meantime, happening on the outside was a sea change in the way that the state was approaching environmental problems. You had this incredible awareness about drinking water problems nationally, certainly here in New York.”

The $585 million state cleanup plan relies on a complex network of new pipes, treatment facilities and containment wells, similar to what the study spurred by Saladino’s bill had said was feasible.

The state says it will take Northrop Grumman and the Navy to court if they refuse to pay.

More than 1,000 residents, meanwhile, have joined class-action and personal injury lawsuits, primarily against Northrop Grumman, that allege their health ailments are a result of the contamination. The company denies responsibility, and the cases are pending in federal court.

As the fighting continues, the plume continues to grow, cleanup costs continue to rise and the health concerns continue to consume many residents.

“It’s the worst-case scenario in every way you can imagine,” said Sarah Meyland, director of the Center for Water Resources Management at New York Institute of Technology in Old Westbury. “The contamination in the groundwater system was known in the ’70s — clearly.”