Over the past decade, Long Island’s blacks, Hispanics and other minorities were far more likely than whites to be arrested and wind up behind bars for a group of crimes that experts say are the suburban equivalent of “stop and frisk” charges, a Newsday investigation shows.

Nonwhites on Long Island were arrested at nearly five times the rate for whites, according to an analysis of police and court records from the years 2005-2016.

For every one Long Island arrest per 1,000 whites, there were on average 4.73 arrests per 1,000 nonwhites, records show. A similar racial pattern existed among those who wound up in jail.

Newsday reviewed more than 100,000 Long Island separate cases involving charges identified as the primary ones resulting from “stop and frisk”-like tactics — such as resisting arrest, obstruction of governmental administration, criminal trespass and a host of drug-related offenses.

The analysis compared the number of arrests involving whites and nonwhites (black, Hispanic, Asian/Indian and others) with the overall Long Island population reported by the U.S. Census. During this time, whites made up on average 73 percent and nonwhites 27 percent of Long Island’s population.

While the state data does not detail how a person was arrested, Long Island police say these types of charges are predominantly the result of pull-over traffic stops. As Suffolk Police Commissioner Timothy Sini explained, “A lot of our police interactions are traffic stops because people are driving in Suffolk County, as opposed to the city where fewer people are driving.”

Police say these arrests are based on legally permissible causes or “reasonable suspicion” discretion by officers, part of an overall crime-reduction strategy. Under the law, police can use their discretion to stop, question and possibly frisk suspects if they believe a crime has been committed.

Riding alone in patrol cars, officers will focus their attention often on “hot spots” — street corners, open spaces or buildings generally found in Long Island minority neighborhoods — where complaints of crime are the highest, officials explain.

“We go to great pains to ensure that our members are not engaged in any forms of biased policing,” says former acting Nassau County Police Commissioner Thomas Krumpter, who retired in July. “A small percentage of the population are responsible for the majority of the crime. We look to target those individuals that, based on their histories, are responsible for that crime in those hot spots.”

But critics say many pull-over arrests are prompted by minor traffic infractions, such as a faulty brake light, that can quickly turn into more serious charges affecting nonwhites in unfair proportions. While white drivers may get a warning or a traffic ticket, they say, nonwhites are more likely to face serious felony charges.

Frank Torres, former president of the Long Island Hispanic Bar Association, and other critics point to recent “stop and frisk” cases — some caught on video — that illustrate what they say is an underlying bias on Long Island that has existed for years.

“All too often I hear, this would not happen to a non-Latino white person,” Torres explains. “The officers will pull someone over for something very minor — a broken taillight, or the headlight is not working or something of that nature. Where otherwise the officer may look away, so to speak, and not bother, but when they see that it’s a person of color or Latino, that’s the basis to stop … and invariably it snowballs.”

While arrests by police are the most serious consequence of overall traffic stops, they account for only a small percentage of stops. More than 90 percent of the thousands of police stops each year wind up in a ticket or just a warning, according to records and police officials.

Newsday’s review of more than 100,000 cases, both felonies and misdemeanors, found one of the sharpest racial distinctions involves arrests for drug possession.

Government studies nationally show little difference in marijuana usage between whites and nonwhites. Yet the Long Island rate of arrests for possession of marijuana is nearly quadruple for minorities than for whites — 5 arrests for 10,000 whites, 20 arrests for 10,000 nonwhites, records show.

And when it comes to drug arrests for having heroin, cocaine and illegal pills (“possession of controlled substances”), nonwhites were overwhelmingly charged with a felony, while whites generally faced a misdemeanor charge with far less chance of going to jail.

Some experts see bias

This pattern of arrests reflects a tale of two different justice systems on Long Island depending on race, some experts say.

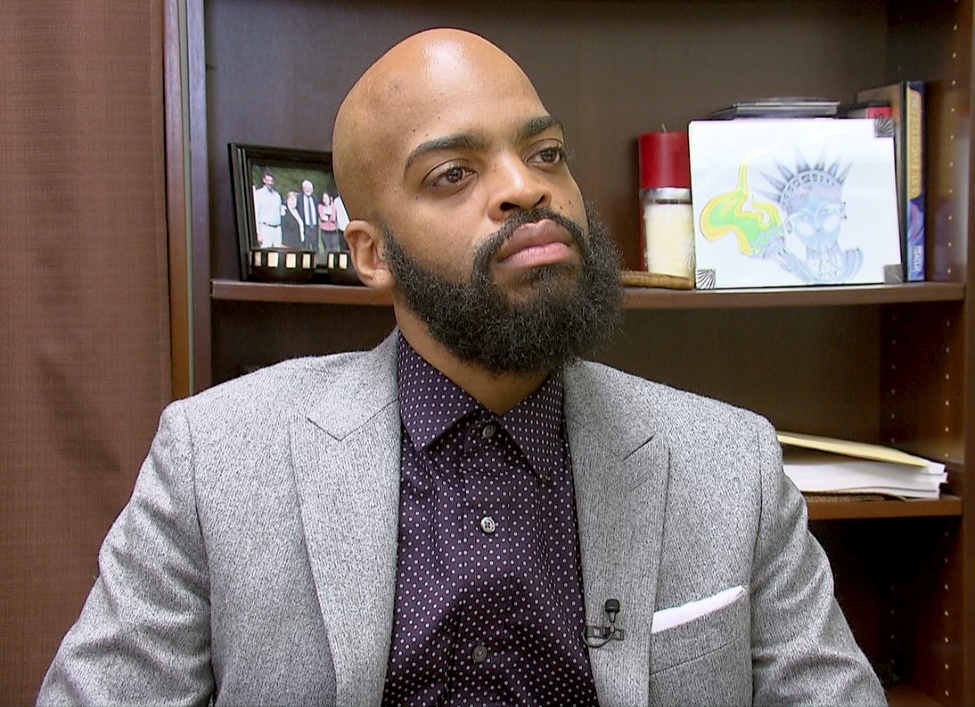

“The anecdotes that we’ve heard here across Long Island, as well some of the data that we’ve actually been able to look at over time, has indicated that indeed there is some sort of racial and ethnic bias in policing here on the Island,” says Jason Starr, formerly director of the Nassau and Suffolk chapters of the New York Civil Liberties Union and chair for the Nassau County Bar Association’s civil rights committee.

Delores Jones-Brown, a law professor at CUNY’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice and founding director of its Center on Race, Crime and Justice, said the Long Island numbers suggest “some racial targeting going on.”

“Disproportionately it is black and Hispanic people who are being arrested for these low-level crimes — which then turn into criminal records that can hurt them for their job opportunities and life chances in the future,” she said.

In Suffolk County, the racial pattern of drivers getting pulled over at traffic stops is part of an ongoing U.S. Justice Department review of policing methods involving minorities. The federal oversight stems from a 2013 settlement agreement prompted by the 2008 hate-crime death of Ecuadorean immigrant Marcelo Lucero and charges of discriminatory police practices.

The Justice Department review includes a comparison of racial patterns in police pull-overs of drivers with the general census population. Examining traffic stops with the racial breakdown of a community is a common approach used by federal authorities and criminal justice experts around the country to test for possible bias.

Nassau’s practices are not under review by the Justice Department, but the federal agency’s effort in Suffolk suggests evidence of some racial disparity in who gets pulled over.

According to an initial report examined by Newsday, more than 28,000 traffic stops made by Suffolk in the first four months of 2015 show blacks and Hispanics were stopped by police more often than would be expected based on census numbers.

Notably, Suffolk blacks accounted for 15.4 percent of traffic stops — far more than what would be expected from their 7.1 percent of the population in the county, documents in the Justice review show. Hispanics also had a higher-than-expected rate. Whites, on the other hand, were less likely to stopped, with 59.2 percent of actual traffic stops compared with their expected number of 71 percent based on the population.

Sini concedes the data reviewed by the Justice Department shows “some disproportionality when it comes to stopping whites and African-Americans” and vows to prevent any unfair racial patterns in who gets arrested by police.

“I’ve talked to many African-Americans in Suffolk County who have said that they have been racially targeted in the past,” Sini said. “Certainly I’ve heard from many folks of color, particularly men, that they’ve had experience in their past where they feel like they’ve been racially targeted.”

Long Island’s pull-over stops and arrests are part of a nationwide debate about policing methods.

President Donald Trump has expressed support for “stop and frisk” methods in New York City as an effective “proactive” crime-fighting tactic to be followed by other localities around the country.

However, this strategy of focusing on certain offenses and neighborhoods — intended to reduce overall crime and improve the quality of life — has sparked concerns about its possible racial overtones.

In November 2013, a New York State attorney general report warned about racial disparities in New York City’s “stop and frisk” policing methods. It found blacks and Hispanics were far more likely to be stopped by police than whites, especially for common charges such as marijuana possession.

Newsday examined 33 different kinds of so-called “stop and frisk” charges — previously reviewed by other government and academic experts in other regions — that applied to Long Island’s suburban setting.

See all of the data

Breaking down arrests: How outcomes differ by race

How we analyzed the data

Long Island police arrest and court data were collected from January 2005 through December 2016 and provided by the state’s Division of Criminal Justice Services. This agency keeps track of numbers regarding arrests, convictions and sentencing reported throughout New York State.

While the state data did not give specific names or the precise location of arrests, it did include age and racial designations for white and nonwhite defendants in each county, including those identified as black, Hispanic, Asian and other minorities. The state data reflect the most serious charge given out at each arrest and include those individuals who may have been arrested more than once in any given year.

Nationally, information about racial patterns in traffic stops and resulting arrests varies widely because of the lack of uniform reporting methods, experts say. “There’s no consistency across states on traffic stops” says Stanford University assistant professor Sharad Goel, co-author of a 20-state analysis of police pull-overs this year.

On Long Island, prosecutors generally leave it up to police departments to monitor concerns about race and ethnicity in who gets pulled over. In addition to their comments about the state arrest data, Nassau and Suffolk police officials were asked by Newsday to provide all available information concerning race and ethnicity regarding arrests and pull-over traffic stops.

In Suffolk, the Justice Department review provides a racial breakdown of traffic stops, without specifics on arrests like the state data. Nassau police provided their own breakdown of race and ethnicity in arrests for a five-year period but said they don’t keep track of traffic stops, nor do they know what percentage of stops wind up in arrests. Newsday’s review found Long Island’s decadelong racial disparity in “stop and frisk”-like arrests continues, with law-enforcement authorities debating how to address it.

Among the findings:

A racial pattern to all Long Island felonies, not just “stop and frisk” charges. In Suffolk County, nonwhites accounted for 25 percent of the population but 53 percent of all felony arrests in the past decade. Similarly in Nassau, nonwhites made up 30 percent of the population but 67 percent of all felony arrests.

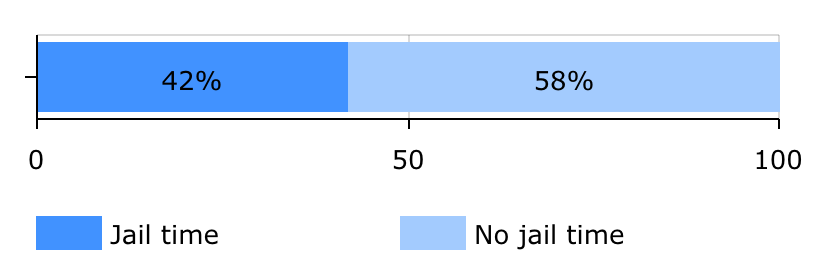

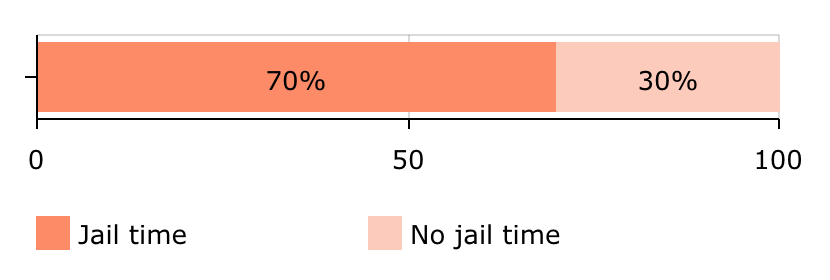

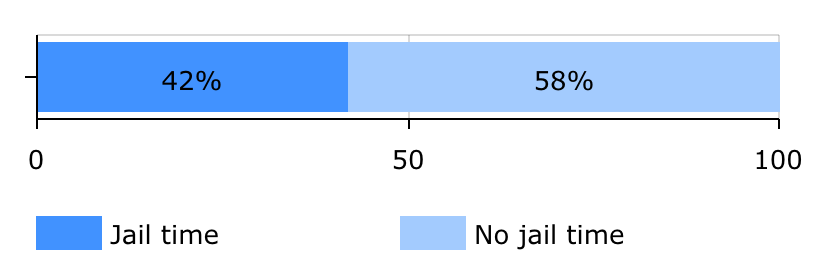

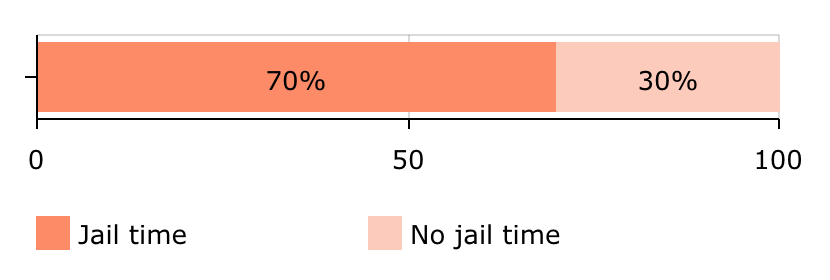

A racial disparity on who goes to jail. Despite guidelines for sentencing consistency, nonwhites on Long Island wound up behind bars far more than whites. In Nassau, for example, 70 percent of felony “stop and frisk” convictions involving nonwhites received jail time, compared with 42 percent of whites. Critics say white drug offenders, especially those with private attorneys, benefit from certain courts and sentencing methods that favor rehabilitation instead of incarceration.

Jail time breakdown among LI white felony offenders

Jail time breakdown among LI Nonwhite felony offenders

Marijuana possession, one of the most common “stop and frisk” offenses, rose last year to its highest arrest level in more than a decade on Long Island. In Nassau, blacks and Hispanics made up 60 percent of marijuana possession arrests — twice their percentage of the population. In New York City, where “stop and frisk” methods have been hotly debated, marijuana possession arrests have dropped by nearly two-thirds since 2011.

Questions about police discretion in certain crimes. A strong Long Island racial pattern exists with criminal charges that critics say rely too much on police discretion — such as resisting arrest and obstruction of governmental administration. For example, while Suffolk blacks and Hispanics account for about one-fifth of the population, they made up more than a half of all resisting-arrest charges in the past decade. While nonwhites make up less than one-third of Nassau’s population, they account for nearly two-thirds of obstruction charges.

Missing numbers and little review. Most Long Island authorities admit they rarely check for racial patterns in arrests and court outcomes, even though it’s recommended by experts. For six years, Nassau County police failed to properly report the number of Hispanic arrests to the state.

Crime down, disparity remains

While reported crime has generally declined over the past decade, racial disparity for those arrested has not.

“In the counties where people use their vehicles and don’t walk as much, a traffic infraction is the equivalent to ‘stop and frisk’ in the city,” says Garden City lawyer Amy Marion, who has represented clients claiming unlawful arrests by police. “You have vehicles being stopped allegedly for a traffic infraction, and that leads to an unlawful search of the person and the vehicle, and other charges being put down against the individual.”

Those who represent Long Island police say racial patterns in “stop and frisk” arrests reflect only where cops are being sent by their supervisors, rather than any inherent bias. Police say they often meet with school, church and community leaders in minority areas, responding to safety concerns about crime.

“No matter what your color is, if you commit a crime — or you appear to be committing a crime — you will be stopped by one of our police officers, and an investigation will ensue that may lead to your arrest,” said James Carver, former president of the Nassau County Police Benevolent Association. “Our police officers don’t look at color. Our police officers only arrest people who commit crimes.”

But many Long Islanders who are black or Hispanic share a story of being stopped at some point by police, with a nagging sense of unfairness based on their race or ethnicity.

Tamara Clark, 49, said she knows what racial profiling by police feels like. The East Brentwood legal secretary says she has an excellent driving record and had “never been arrested, thank God.” But she recalls how a Suffolk officer once pulled her over in her car while she was driving to a neighborhood store with her young son.

“I was pulled over randomly and I said, ‘Is there anything wrong?’” Clark recalled. “If you’re just looking for random purposes for a black male or black female, you can’t just can’t pull every black male and every black female over, or every Hispanic male and Hispanic female over.”

Police quizzed her and then let her go, she said, without any explanation. “I feel if I didn’t stand up for myself and continue to ask why and what was his reason, it could have led to a little more than that,” Clark said.

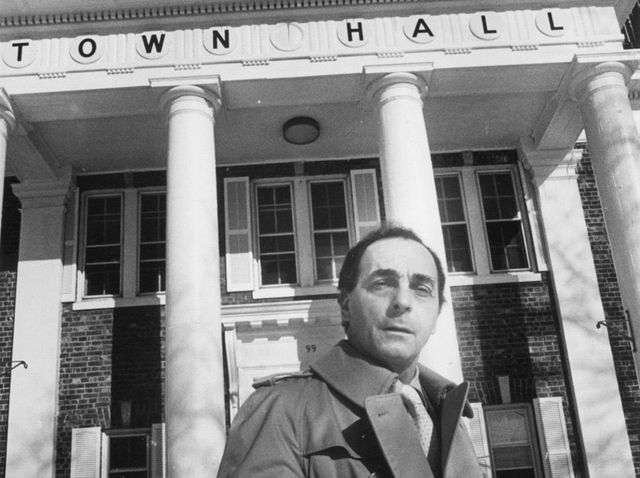

Attorney Fred Brewington, who has handled several lawsuits against police in which race played a factor, said resisting arrest is among a group of questionable “stop and frisk” offenses commonly cited by police.

“The police officer who decides to charge someone — with obstruction of governmental administration, resisting arrest, disorderly conduct — has an enormous amount of discretion,” said Brewington. He said “reasonable suspicion” legal grounds during a pull-over stop — particularly with white cops dealing with minorities — “allows them the opportunity to utilize their authority and the law to mask other deep-rooted issues.”

Newsday’s review showed resisting-arrest charges against nonwhites on Long Island are far more common than for whites. In Nassau, while nonwhites account for 30 percent of the county’s population, they made up 63 percent of resisting-arrest charges during the past decade. A similar disparity exists in Suffolk, records show.

Obstruction of governmental administration — a charge that critics say relies on a wide latitude in police discretion — also has a sharp racial pattern. In Nassau, 67 percent of all OGA arrests in the past decade involved minorities.

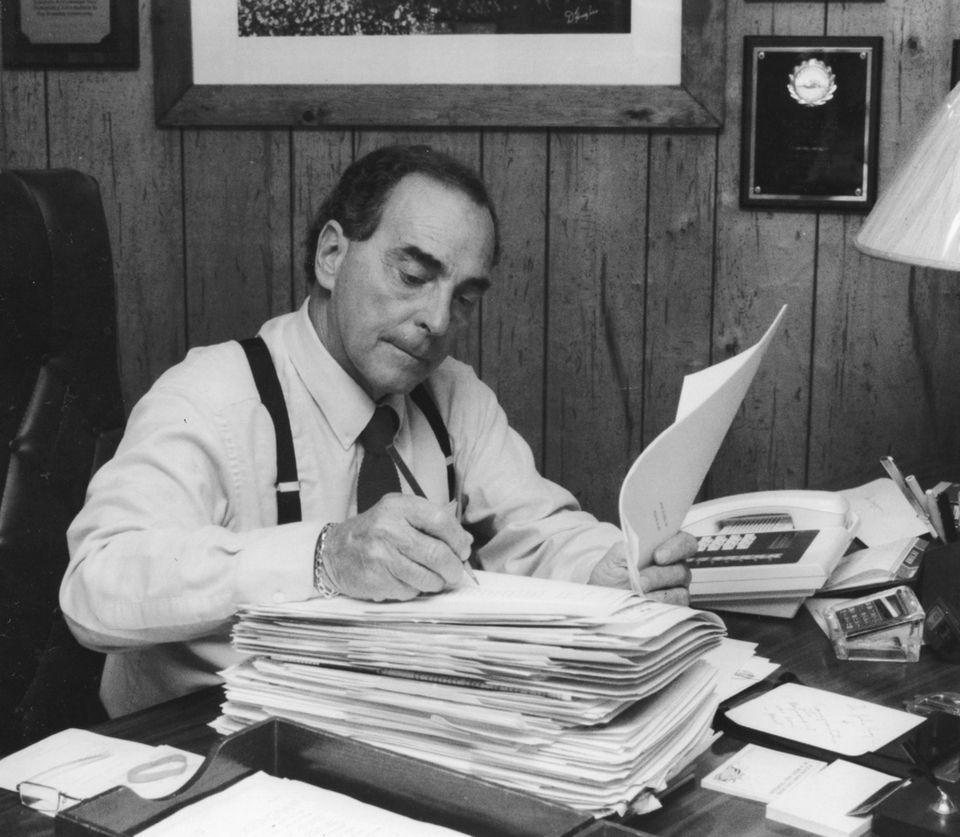

Nassau’s former acting commissioner Krumpter denied any allegations of bias in the department. “There are always going to be a few bad apples and in those cases here in Nassau County, we take aggressive action,” Krumpter explained. “We will not tolerate misconduct by our police officers.” He objected to the term “stop and frisk” and said most pull-overs by police result in questioning rather than any physical contact.

Arrests vs. population data

Criminal justice experts, such as Jones-Brown, say local law-enforcement officials should routinely compare arrest patterns with the racial makeup of their community to ensure there is no bias or racial profiling. The National Institute of Justice, the research arm of the U.S. Department of Justice, has recommended police officials conduct inspections and audits as a preventive.

“It’s an important starting point,” Jones-Brown said of comparing arrests to the general population. “It is easy to deny the existence of racial profiling if we are not looking at any data.”

But Newsday found Long Island prosecutors generally don’t check for racial profiling in arrests, convictions or sentencing — despite several high-profile disputes in recent years, including the ongoing Justice Department settlement in Suffolk.

“The answer to that is no,” said a spokesman for Nassau County District Attorney Madeline Singas, when asked about an overall review for racial patterns. “We analyze the facts and circumstances of each arrest on a case-by-case basis.” Suffolk District Attorney Thomas Spota declined to comment, according to a spokesperson who said concerns about racial patterns are left to police officials.

As criminal arrest cases go to court, Newsday also found, there exists a racial disparity in who winds up in jail.

Nonwhites on Long Island arrested on “stop and frisk” charges were more likely to land behind bars (local jail or state prison) than whites charged with the same offense.

For example, during the past decade in Nassau County, for every felony “stop and frisk” conviction involving nonwhites, 70 percent wound up behind bars, while 42 percent of whites faced jail time. Similarly, 66 percent of Suffolk minorities convicted of such felonies were incarcerated but only 40 percent of whites.

Even with low-level misdemeanors in both counties, the rate of going to jail is almost double for minorities.

Sini said his department has improved its review of race and police practices, based on the data of police pull-overs prepared as part of the Justice Department’s 2014 oversight agreement. Suffolk has also stepped up efforts to improve relations with minority communities, he said. Subsequent compliance reports under the Justice agreement have cited better bilingual handling of complaints and screening of new officer applicants for any history of bias.

Overall, the draft report on four months of 2015 data shows that Suffolk traffic stops resulted in a ticket (65 percent of the time) or a warning (30 percent). Less than 2 percent were criminally arrested, said the report, which didn’t provide any analysis of who gets charged, convicted and goes to jail.

“There were more traffic stops for Black, Hispanic and Mixed Race drivers,” the report said. Conversely, it found, “White drivers were less likely to be searched, receive a ticket, be arrested, or have any kind of action taken against them than non-White drivers.”

Sini says the Justice Department’s input is “tremendously value added. It’s almost like having a free consultant.” He said his department is working on refining its reporting methods to reach full compliance under the federal agreement.

A June 2017 Justice update report found Suffolk only in “partial compliance” and working to correct “various shortcomings” found in its traffic stop data methods to detect racial bias.

However, traffic stops only tell part of the story. Newsday’s analysis of the past decade shows a far greater racial disparity exists on Long Island once there is a pull-over arrest, particularly for a felony.

In general, the more serious the crime, the greater the chance of being charged for blacks and Hispanics. And instead of facing monetary fines or points off their driver’s license, they face a greater likelihood of spending time behind bars if convicted, records show.

Nassau’s Krumpter rejected comparisons of arrests to the general population, even though it’s a common standard used by the Justice Department and criminal justice experts. He believes the racial breakdown of arrests should be compared with all criminals in Nassau County at any given time, rather than the general population. He acknowledges no such data comparison now exists.

“Population [comparison] doesn’t take into consideration the transient public who comes into Nassau from other parts of the city and from Suffolk County,” Krumpter explained. “A lot of times, the communities that are predominantly minority you’ll find have a high propensity for crime. And we are very focused on being fair and unbiased here in Nassau County.”

Though Nassau arrest records suggest a comparable racial pattern to Suffolk, there is no similar Justice Department review of its practices, officials said. Krumpter said the department has consistently monitored data for racial patterns. However, when asked about traffic stop data, a Nassau police spokesman said the department was “unable to provide as we don’t track that.” Similarly, the department said it could not say what percentage of traffic stops wound up in arrests.

In response to Newsday’s request, however, Nassau provided its own arrest statistics for the five most recently available years for all misdemeanors, felonies, and violations such as disorderly conduct. It shows whites accounted for 59 percent of all arrests — less than their percentage of Nassau’s resident census population.

However, blacks in Nassau County made up 34 percent of all arrests — approximately three times their 11 percent of the county’s 2010 Census population. These Nassau statistics do not mention Hispanic arrests, which are intermingled in other racial categories, officials said.

Newsday’s investigation found properly counting Hispanic arrests has been a problem in Nassau. For six years, from 2007 to 2012, Nassau police failed to properly report Hispanic arrests to New York state Division of Criminal Justice Services — leaving the category blank in its filings — until the error was eventually corrected in 2013.

State officials first “identified the problem” in early 2008 and worked with its vendor to fix it, said Janine Kava, spokeswoman for the state Division of Criminal Justice Services. “That process took four years — we do not know why it took so long — that would be a question for … [Nassau County officials].” She said the six-year period of arrest data has never been updated by Nassau with the state.

Nassau said it is now reporting Hispanic arrests correctly to the state. “We made the adjustment and made the corrections,” Krumpter said.

Torres called “shameful” the six-year error in reporting Hispanic arrests in Nassau and said both the district attorney and police should check regularly for possible racial profiling. Hispanics account for about 15 percent of Nassau’s population during the dozen years studied.

“What purpose does it serve if you don’t know the categories of individuals being arrested as far as their ethnic or racial background?” Torres said. “That would help into determining whether there is racial profiling or disparity among the arrests here in Nassau County.”

Nassau’s new acting commissioner, Patrick J. Ryder, who replaced Krumpter in July, declined to be interviewed. But in a written statement, Ryder said his department “will analyze data, thus taking into account variables such as Hot Spot policing, crime trends, calls for service and community outcry when determining where additional resources will be assigned.”

‘Hot spots’ and race

Driving in an undercover car, Suffolk Det. Sgt. Mike McDowell recently explained the delicate balance for police in trying to solve crime in “hot spots” within predominantly minority communities without falling into racial profiling.

“A person’s race should have no bearing on why a person is stopped or arrested — it should not come into play,” explained McDowell, a 21-year veteran. Cops patrolling Suffolk go through “an ongoing and continuous training of how to avoid racial profiling, about the pitfalls and legal ramifications of racial profiling,” he said.

“Hot spot” policing, as it’s been practiced around the nation in the past decade, is designed to concentrate police resources in areas where it is most needed. Both Long Island top police officials say they deploy cops into these areas based on a careful analysis of crime stats, victim and neighborhood complaints, and informants tipping them to where suspects may be found.

But critics blame “hot-spot” policing methods for both the stark racial contrast in Long Island arrests over the past decade as well as sweeping up young people in nonwhite communities into the criminal justice system in a way that white youngsters in more affluent neighborhoods generally don’t face.

“The vast majority have had some sort of bad encounter with the police — from simple discourtesy all the way to more serious encounters,” said Starr about black and Hispanic young people. “You begin to feel more like a target because of what you look like than a partner in trying to keep your own community safe.”

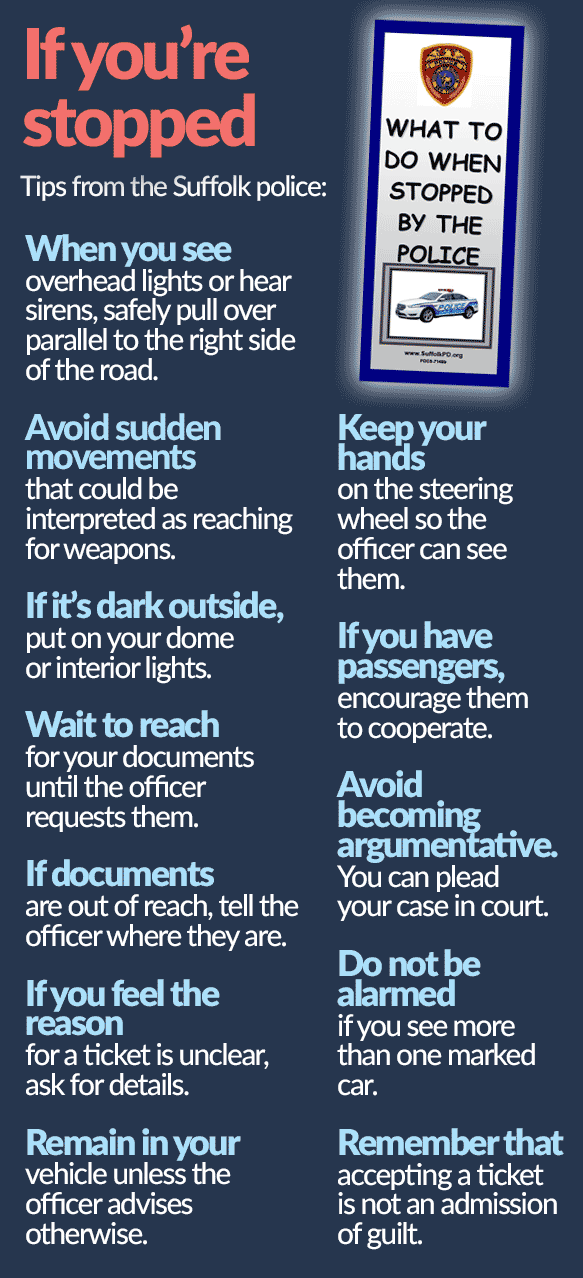

At STRONG Youth Inc. in Uniondale, a youth and community development group, staffers teach young people how to deal appropriately with police, even if they feel they are being treated unfairly.

“Our young people are constantly coming into contact with law enforcement,” said executive director Rahsmia Zatar. “We know that racial profiling is a real issue. It’s not something that’s made up. Unfortunately, especially our young men of color are constantly being approached.”

As Long Island’s population becomes more diverse, law-enforcement officials say it’s necessary to make sure there are no unfair patterns in pull-over stops, arrests or in the racial makeup of its police force.

Sini said understanding racial disparity is matter of both the hard numbers in police statistics as well as the public perception based on their own experiences. Sini is running for Suffolk district attorney, seeking to replace longtime incumbent Thomas Spota, who is retiring.

“The question is why? Is there legitimate reasons explaining that disproportionality, or is there an element of biased policing going on, whether it’s intentional or unintentional?” said Sini, recalling concerns about racial disparity he’s heard since becoming Suffolk’s top cop. “I think it’s very important as commissioner to recognize the validity of that sentiment. Or the police will have no legitimacy whatsoever with communities of color.”

Top image credit: iStock/kali9

Homepage image credit: iStock/m-imagephotography; composite photo posed by models.

JS Chart by amCharts

Read Part 2 of the series

Breaking down arrests: How outcomes differ by race

See all of the data