The report does not describe Franqui having a gun outside of the house, or firing on an officer. It only states that the officers “were able to get Franqui out of the house, but he attempted to go back into the house. Police officers gave chase and Franqui discharged a handgun into the ceiling during the ensuing struggle with police.”

Franqui was charged with several felonies, including menacing a police officer, reckless endangerment, second-degree assault and criminal possession of a weapon in the second degree. An officer also claimed in a misdemeanor charging document that Franqui possessed a .22 Derringer inside his house.

He was never charged with attempted murder of a police officer.

Yet within the Seventh Precinct, Franqui would be remembered as the guy who tried to shoot a cop.

Franqui filed a notice of claim against the Seventh Precinct in February 2012, alleging that he was physically beaten during the arrest at his home. He sought $7.2 million for personal injuries.

Repp said that Internal Affairs Bureau officers investigating the excessive force allegations visited her while Franqui was in jail.

She said she told them that during the arrest, officers shot Franqui with a Taser multiple times, “hogtied” him with black electrical tape and dragged him down the front steps of his house, “allowing his chin to hit every step.” Repp said officers kicked Franqui in the head and stomach and “took turns beating the crap out of him.”

According to Repp, who has no known criminal convictions, the IA investigators rewrote her statement “in the way they wanted it to sound.” She said, for example, that they refused to include in her statement that police had used electrical tape to hogtie Franqui.

Each time, “they either told me I was fabricating it, my words were wrong, or they just changed my words for me,” Repp said.

Anthony Grandinette, an attorney representing Franqui’s family in a civil rights lawsuit filed in federal court against Suffolk County and its police department, said Franqui spent three weeks in the hospital after his arrest due to injuries inflicted by police. An arrest warrant shows that officers took Franqui into custody at John T. Mather Memorial Hospital in Port Jefferson on Dec. 22, 2011, three weeks after his arrest. In applying for the warrant, a detective stated that Franqui was at the hospital for a “psychological evaluation.”

Franqui spent roughly a year after his arrest at the Suffolk County Jail in Riverhead because he was unable to post a $40,000 bond. He mailed to Repp from jail more than a dozen handwritten letters, which provide a manic portrait of his psyche while locked up.

“Maybe finally having you in my life did make me crazy but then I should be in a [psych] ward not in jail,” Franqui wrote in one letter spotted with blood, which he said came from cutting his hand in a fight. He said while in jail he had been forced to join a gang, “as much as I hate them.”

And he repeatedly accused the police of beating him up and lying about it.

“I know you were just scared and I don’t blame you but the people you called are even more [expletive] up than I am,” Franqui wrote of the police. “They had just been waiting for the chance to beat me up and put me behind bars and that’s why they are lying so much.”

Franqui wrote that the officers had trumped up the charges against him by falsely accusing him of exiting his house with a gun. The officer with the fractured hand, Franqui wrote, injured himself by punching Franqui unconscious. “I wasn’t trying to hurt the cops just myself,” Franqui wrote.

Franqui would plead guilty on Dec. 5, 2012, to second-degree felony attempted criminal possession of a weapon, resulting in a sentence of 6 months’ imprisonment and 5 years of probation, which included psychiatric and psychological conditions. Because Franqui had already spent a year at the Suffolk County jail, he was ordered released. A judge warned him that he faced 7 years in an upstate prison if he violated probation.

Franqui left jail certain that police would come up with a “brilliant plan” to set him up because he had filed the legal claim and accused them of brutality, according to his friend Kyle Fox, of Rocky Point. “He came out more looking over his shoulders because he was afraid the cops were going to get him,” Fox said.

Suffolk police and a probation officer raided Franqui’s dad’s house on Jan. 9, 2013, less than two months after Franqui had been released from jail. Franqui was living in his father’s garage because he had lost his job, his car and his home during his stint in jail.

Franqui’s father, Joaquin, said he was present when the raid occurred and that officers “stormed in the house yelling, with guns out.” Though Franqui’s sentence subjected him to random visits and searches by police and probation officers, available police documents do not explain the show of force that Joaquin Franqui said occurred.

A search of Franqui’s de facto bedroom resulted in two more criminal charges. One, for unlawful possession of marijuana, was for two clear plastic bags of the drug. Though an arrest report does not state the amount of marijuana, the charge is typically punishable by a fine not exceeding $100. Franqui — who had a cartoon of a pot leaf tattooed on his back — told officers that he smoked marijuana “because it helps me with my anxiety.”

The more serious charge against Franqui was for third-degree felony criminal possession of a weapon. As described in a police report, the confiscated weapon was a “wrist-brace type slingshot.”

“I actually didn’t even know it was there,” Franqui would tell the judge of the slingshot. He spent nine more days in Suffolk County’s Riverhead jail.

Franqui’s aunt, Michelle Dionisio, said her nephew got the slingshot when he was a boy. Dionisio said the weapons charge is evidence that Franqui’s paranoia was justified and that officers set out to harass her nephew as payback for the 2011 shooting.

“It would be different if this was a hardened criminal that would cause them to raid him like that,” Dionisio said. “What did they find? A slingshot, from when he was 10 to 12 years old.”

Four days after getting out of jail, Franqui again found himself staring at the barrel of a service weapon brandished by an officer of the SCPD’s Seventh Precinct.

On Jan. 23, 2013, a Wednesday morning in the midst of a brutal cold snap in which the temperature dipped to 10 degrees, Franqui drove with Dog to Shoreham in a rusted 1972 Cadillac Eldorado. He had recently acquired the car, his father said, for $200 and a crucifix necklace, and he wanted to show it off to his friend, Simon Earl.

A fellow resident of Earl’s upscale neighborhood would later tell the special grand jury that he had a feeling “something was not right” as he watched the driver of the old Cadillac move slowly through the neighborhood. Seeing a young man wearing a hoodie get into the vehicle, the resident said he feared potential burglaries. He called a retired police officer who lived nearby, and they called 911 to report a suspicious vehicle in the neighborhood.

Earl, in a hooded sweatshirt, was checking out his friend’s new ride as contractors worked on his parents’ home. From her patrol car, Suffolk Officer Karen Grenia ran the license plate number on the gold Cadillac parked in front of Earl’s home on Cordwood Path. A dispatcher responded that the car belonged to Franqui.

Grenia would later testify before the special grand jury that she recognized Franqui’s name, characterizing him as the person who had discharged a firearm at other Seventh Precinct police officers.

She pulled her gun and ordered Franqui out of the Cadillac, she told the special grand jury, “for fear that Franqui may have had another weapon.”

Darryl Moore, a contractor remodeling the Earl family’s home, recalled during a legal deposition that Grenia yelled, “Don’t F’in move” as she pointed her gun at Franqui. Grenia was “dropping F bombs, four-letter words,” Moore said.

Asked if he had ever witnessed such a scene, Moore responded, “Just on TV.” (According to court records, Grenia has been the subject of “at least 10” civilian complaints, most for “unprofessional language.”)

Grenia was “yelling extremely loud and giving inconsistent orders,” according to a sworn statement from Moore’s carpenter, Jay Moshier. “It was a volatile situation but both Simon and the person in the car remained calm and obeyed the female officer’s orders.”

Police reports, however, do not describe Franqui as compliant. Grenia later claimed in an arrest report that, with her gun trained on him, Franqui opened his door and told Dog: “Go get her.”

Grenia, referring to Franqui’s dog as a “pinscher,” wrote that the animal’s release was “only prevented” when she “slammed the vehicle door shut before the animal could exit.”

In his affidavit, carpenter Moshier stated of the claim that Franqui had ordered his dog to attack the officer, “I never observed that ever happen.” However, Grenia would be lauded by department brass for her quick instincts in thwarting the potential dog attack.

“He has a Doberman in the car and he said ‘get her,’ ” Det. Lt. John “Jack” Fitzpatrick, then-commander of the Suffolk homicide squad, told Newsday when recounting Franqui’s arrest for an article published the next day. “She’s so alert, she slams the door back closed.”

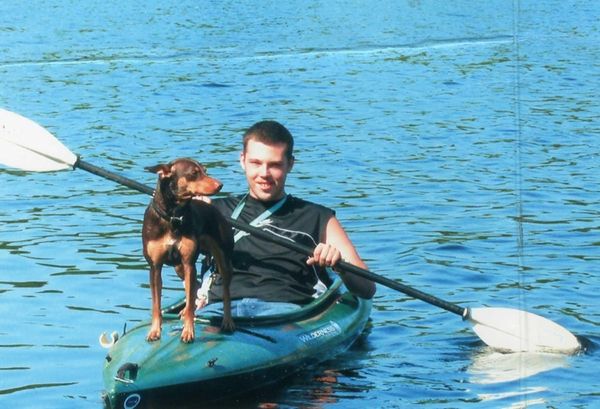

Dog is neither a Doberman nor a pinscher. He’s a Manchester terrier, small enough to stand on the bow of Franqui’s kayak as he paddled around Long Island Sound.

By Grenia’s count, 15 to 20 officers streamed to Cordwood Path to assist her arrest of Franqui, including an off-duty officer who lived nearby. At least two of the officers had also been on the scene during Franqui’s 2011 altercation.

Earl, a 27-year-old geology student with no criminal record, said he was just looking at the engine of Franqui’s Cadillac when Grenia unholstered her gun and pointed it at him. Moshier and Moore corroborated that account, and Grenia did not deny the allegation during a court appearance.

Moshier said he watched as Earl was handcuffed and put in the backseat of a police car, although he would not be charged with any crime.

According to Grenia’s deposition, police Officers Nicholas Robbins and Janine Lesiewicz — one of the officers at the 2011 incident — then entered Earl’s home. The house is owned by Earl’s parents, who were not there.

The officers walked throughout the house, riffling through ashtrays, mail and cabinets, the contractor, Moore, later said in sworn testimony. Moore said he asked one of the officers whether they had permission to enter the house, and the officer responded: “What, are you hiding something?”

Grenia, during her own deposition, said Earl invited an officer into the house while he searched for identification, which the officers needed as proof that he lived there. “We did not know, in fact, they did not just burglarize that house,” Grenia said.

In a joint lawsuit filed with Franqui’s estate, Earl’s family claims officers never had permission to enter their home and illegally searched it without a warrant. The suit alleges that Earl was wrongfully handcuffed, searched and detained despite no evidence that he had done anything illegal. The suit also claims Grenia continued to harass Earl because he was “a witness to the initial police misconduct against himself” and Franqui. Court records show that in April 2014, Suffolk County attempted to settle the lawsuit with the Earl family for a judgment of $5,001. The family did not accept.

Grenia said in court testimony that after Franqui’s arrest, she drove into the Earls’ driveway and recorded the license plate number of Simon Earl’s gold 2000 Volvo. She gave no reason for that in court.

On April 9, 2013 — less than three months after arresting Franqui — Grenia stopped Earl’s Volvo about a half-mile from his house, at North Country Road and Norman Drive in Shoreham. According to her court testimony, she had passed the car and then watched in her rearview mirror as Earl made a right turn without signaling.

Grenia testified that she did not recognize the vehicle as Earl’s and only kept her eye on the car because there is a lot of “drug traffic” on the “backcountry winding roads.”

“I don’t know if somebody’s doing drugs or trafficking drugs until I pull them over,” she said.

Upon recognizing Earl, Grenia said, she called for backup to prevent him from making false allegations against her. “If we think there’s going to be a problem, we have another set of eyes,” she explained.

Earl informed her that he would be recording video of the traffic stop with his phone, and Grenia took the phone, turned it off and put it on top of Earl’s car. Grenia explained in court that “cell phones have been used as Tasers or different weapons.”

Officers instructed Earl to exit his vehicle, and he was patted down. Earl claimed that despite explicitly denying the officers permission to search his car, “they searched my vehicle down to the floor mats.”

Grenia acknowledged entering the back of Earl’s vehicle, but only to help find his insurance card.

Grenia ticketed Earl for not producing an insurance card and for failing to signal before turning. He pleaded not guilty in a September 2014 traffic court appearance, where a judge dismissed the violation and ruled that the government had “not proved their case.”

Franqui was placed under arrest at Earl’s house for allegedly ordering Dog to attack Grenia, for which he would be charged with obstruction of governmental administration and, after allegedly admitting to Grenia that he had smoked marijuana 30 minutes earlier, for driving while under the influence of drugs.

Grenia also charged Franqui with resisting arrest because she alleged that he “flailed his arms and legs and refused to put his hands behind his back until he was eventually subdued.”

Franqui suffered several injuries during the arrest, according to police records and special grand jury testimony. He had a large scrape across his left cheek, which would still be visible at his open-casket funeral. A medical examiner’s report described blunt impact injuries to his body, including his torso and upper and lower extremities. The medical examiner’s office found that Franqui’s injuries, including the cheek wound and “injuries on the front of his body,” were consistent with “having occurred during [the] time he was placed under arrest by police.”

Franqui was booked at the Seventh Precinct at 12:28 p.m. The morning shift supervisor noted the scrape on Franqui’s cheek and wrote in a prisoner log that he “appears intoxicated unsteady slurred speech.” The supervisor also wrote that Franqui said “he’s being treated for anti-anxiety but doesn’t need medication at this time.”

Franqui entered a holding cell at 2:25 p.m. In conversations with a prisoner locked up two cells away, Franqui exhibited wild mood swings, at times speaking calmly and then breaking into angry, paranoid rants or uncontrolled sobs of anguish. He insisted that police had “roughed him up and that he shouldn’t have been arrested.”

About three hours after he was locked up, Franqui’s mother called the Seventh Precinct and spoke to the supervisor, Sgt. Kevin O’Reilly.

“My son is being harassed and I’m really at the end of my rope,” Phyllis Daily told O’Reilly in the recorded phone call. She asked to speak to her son and the precinct commander.

O’Reilly denied both requests. “Ma’am, I’m going to hang the phone up right now on you,” he said. “If you want to see your son, you can go to first district court tomorrow morning.”

Jack Franqui was dead within the hour.

Read Part 2