Football helmets, the iconic piece of equipment in America’s most popular sport, are at the center of the debate over concussions that is roiling the way the game is played at all levels.

On Long Island, there are nearly 10,000 student-athletes playing football on 239 varsity, junior varsity and freshman teams at 116 high schools.

Experts say the helmet is the last line of defense against head injuries. But how well a helmet can help prevent a concussion is a source of controversy among neurologists, medical researchers, helmet manufacturers and football coaches.

A typical high school football player receives about 650 hits to the head per season, according to researchers at Purdue University and the University of Michigan. The impacts of those hits are the equivalent of what a seat-belted passenger experiences in car accidents ranging from 15-to-35 mph, according to University of Nebraska professor Timothy Gay, author of “The Physics of Football.”

There are many factors that contribute to concussions: speed, acceleration, the angle of a tackle and a player’s physical size among them. Players are bigger and stronger than ever before, which presents enormous challenges to the efforts to protect them from head injuries. Neurologists also don’t know why some hits cause concussions in certain players and not in others.

A seven-month Newsday examination into head safety in high school football on Long Island — which included analyzing concussion reports from 104 of the 116 schools and helmet inventories from 108 schools and interviews with more than 80 neurologists, researchers, helmet manufacturers, state athletic officials, superintendents, athletic directors, coaches, players and parents — found:

— Entering this football season there were 885 football helmets in circulation that are classified as “low performers” at reducing the risk of concussion, according to safety ratings that Virginia Tech researchers have been publishing since 2011. The testing grades helmets on their ability to reduce head acceleration within the helmet on impact. A five-star helmet is the best at reducing the risk of concussion. A one-star helmet is the least effective. The study’s lead author, Stefan Duma, is surprised these 885 one- and two-star helmets remain in circulation. “Four years later these should have definitely been phased out,” he said.

— There are 60 schools with one- or two-star helmets in inventories obtained by Newsday. In response to Newsday’s inquiries, 18 schools said they either removed those helmets from their inventories or did not issue them to athletes this season.

— New Hyde Park, in the Sewanhaka school district, has the most with 71 one-star helmets in its inventory. District Superintendent Ralph Ferrie said in July he was comfortable with players still wearing one-star helmets because they meet the safety standards set by the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (NOCSAE), which oversees helmet use in football on all levels. Despite Ferrie’s previous comments, the district purchased 160 five-star helmets on Tuesday for $38,400 and said it plans to swap out all of the one- and two-star helmets currently being worn when the helmets arrive Friday, a district spokeswoman said.

— Of the 9,502 helmets in circulation at 108 of the 116 high schools that responded to Newsday’s request, there were 2,898 five-star (30.5 percent) and 4,576 four-star (48.2 percent) helmets. Another 408 (4.3 percent) have no rating because they are more than 5 years old and were no longer being made when Virginia Tech released its first ratings in 2011.

— There were 364 reported concussions during practices or games last season at districts covering 88 public high schools and two private schools.

—There were 14 high schools that said they had no football players suffer concussions on any of their teams, including varsity, junior varsity and freshman.

— Six players on Long Island were not cleared to return to athletic activities for more than four months because of lingering concussion symptoms. The longest time missed was 202 days.

Find your school’s helmet inventory

‘Brain was rebooting’

Yusuf Young doesn’t remember much about the final plays of his high school football career.

The former Roosevelt High School linebacker was playing in last year’s Long Island championship game against Shoreham-Wading River when a swarm of blockers came his way during a third-quarter running play. He stepped into the path of the oncoming bodies and took the brunt of a blocker’s helmet-to-helmet hit.

On the next play, Young was knocked to the ground, and, according to the school’s concussion incident report, hit his head on the ground.

“At first I didn’t think I was hurt that bad,” Young said. “I tried to stay in the game, but it was like I kept falling, I was so weak . . . It felt like my brain was rebooting.”

Young stayed in the game for two more plays. When he returned to the sideline, he dropped to his knees and tumbled to the ground. As he was being checked by a physician on the sideline, he said his mom rushed to his side and, through tears, implored him to go to the hospital. Young was taken by ambulance to an emergency room at Stony Brook University Hospital, where doctors told him he had suffered a concussion.

Young, now 18, graduated from Roosevelt in June and is attending Nassau Community College this fall.

Young was the only Roosevelt player removed from play last season on either the JV or varsity because of a concussion, according to documents obtained by Newsday.

The school’s incident report said Young was confused, dizzy and was sensitive to noise in the aftermath of the hits to the head.

According to a doctor’s note, Young returned to school the next day following the concussion but “was sent home because he was feeling drowsy.” Young said the school’s athletic director, Michael Jones, drove him home.

“I know I wouldn’t want my kid walking home after something like that,” Jones said.

Paperwork provided by the school indicates that Young began the school’s return-to-play protocol that Thursday, five days after the concussion.

The protocol, part of New York’s concussion management act of 2012, includes gradually increasing a player’s activity level for a series of days. He was cleared to return to sports by the school physician Dec. 10, nearly two weeks after the concussion.

Helmet testing

Stefan Duma, a biomedical engineering professor, said he modeled Virginia Tech’s independently funded helmet rating system after the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s five-star car safety rating system.

Some neurologists say Virginia Tech’s ratings overinflate a helmet’s role in preventing concussions and oversimplify the complexities behind the science of concussions. However, just as safety testing changed the way the automobile industry made cars, Virginia Tech’s ratings changed the way football helmets are made.

The number of five-star helmet models being manufactured has risen to eight from one since the ratings were first made public in 2011.

Riddell makes the most helmets in use on Long Island, followed by Schutt, Xenith and Rawlings, which announced in June it will no longer produce football helmets because it was not profitable enough.

Riddell credited the Virginia Tech ratings for encouraging schools to accelerate their helmet replacement plans.

“We think kids should be in the best available technology,” said Thad Ide, Riddell’s senior vice president for research and product development.

Xenith chief executive Joe Esposito called the ratings “the de facto industry standard” and said Xenith wouldn’t put a new helmet on the market that wasn’t five stars.

On Long Island, two schools — Oyster Bay and Port Jefferson — replaced their inventories with all new five-star helmets after the death of Shoreham-Wading River junior Thomas Cutinella following a helmet-to-helmet hit last year. Port Jefferson spent $14,749 on 50 new five-star helmets. Oyster Bay spent $33,915 on 85 five-star helmets equipped with a sensor system that alerts a handheld device when a hit registers above a certain threshold of force.

Northport is the only other school with all five-star helmets. Typically, schools buy about 10 helmets per year, according to purchase orders obtained by Newsday.

Helmets worn by high school players are the same makes and models as those worn in the NFL. The league says it’s “mandatory” that teams make the Virginia Tech ratings available to players, a spokesman said.

Schutt chief executive Robert Erb, who lives in Manhasset, described the ratings as “one piece of information with all sorts of caveats.”

Schutt’s website touts that it makes the highest-rated helmet, but Erb doesn’t believe the ratings indicate which helmet is best at reducing concussion risk.

“There are simply too many variables taking place on a football field for such testing to be predictive of risk reduction,” Erb said.

But Dr. Michael Egnor, a professor of neurosurgery at the Stony Brook University School of Medicine, said Duma’s team has done “the best and most rigorous work” studying which helmets decrease head acceleration the best.

“And if it were my kid, I would want him to be wearing one of the higher-rated helmets,” Egnor said.

Other experts agree.

“I would not put my kid in one of those one-star helmets,” said Kevin Guskiewicz, co-director of the University of North Carolina’s Sport-Related Traumatic Brain Injury Research Center and a member of the NFL’s Head, Neck and Spine Committee.

Virginia Tech tests helmets in a laboratory by dropping them 120 times from predetermined heights to simulate the different forces of impacts that its research says a football player would expect to experience during a season.

A separate six-year study by researchers from eight universities, including Virginia Tech, tracked the force of impacts and concussions suffered by college football players from 2005 to 2010 wearing a one-star helmet and a four-star helmet. The researchers determined there was a 54 percent reduction in concussions among players in the four-star helmet compared with the one-star.

But just as injuries and deaths can happen to people in a car with a five-star safety rating, Duma says that a five-star helmet by no means guarantees someone won’t get a concussion.

“There’s always going to be a risk,” Duma said. “It’s about risk reduction . . . At the end of the day, I ask people this simple question: Do you want to wear a helmet that lowers head acceleration or not? We tell you which ones lower head acceleration better than others, and you can pick.”

NFL players choose which helmet to wear. The Giants’ Odell Beckham Jr. wears a five-star helmet, the Jets’ Darrelle Revis wears a four-star helmet and New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady wears a one-star.

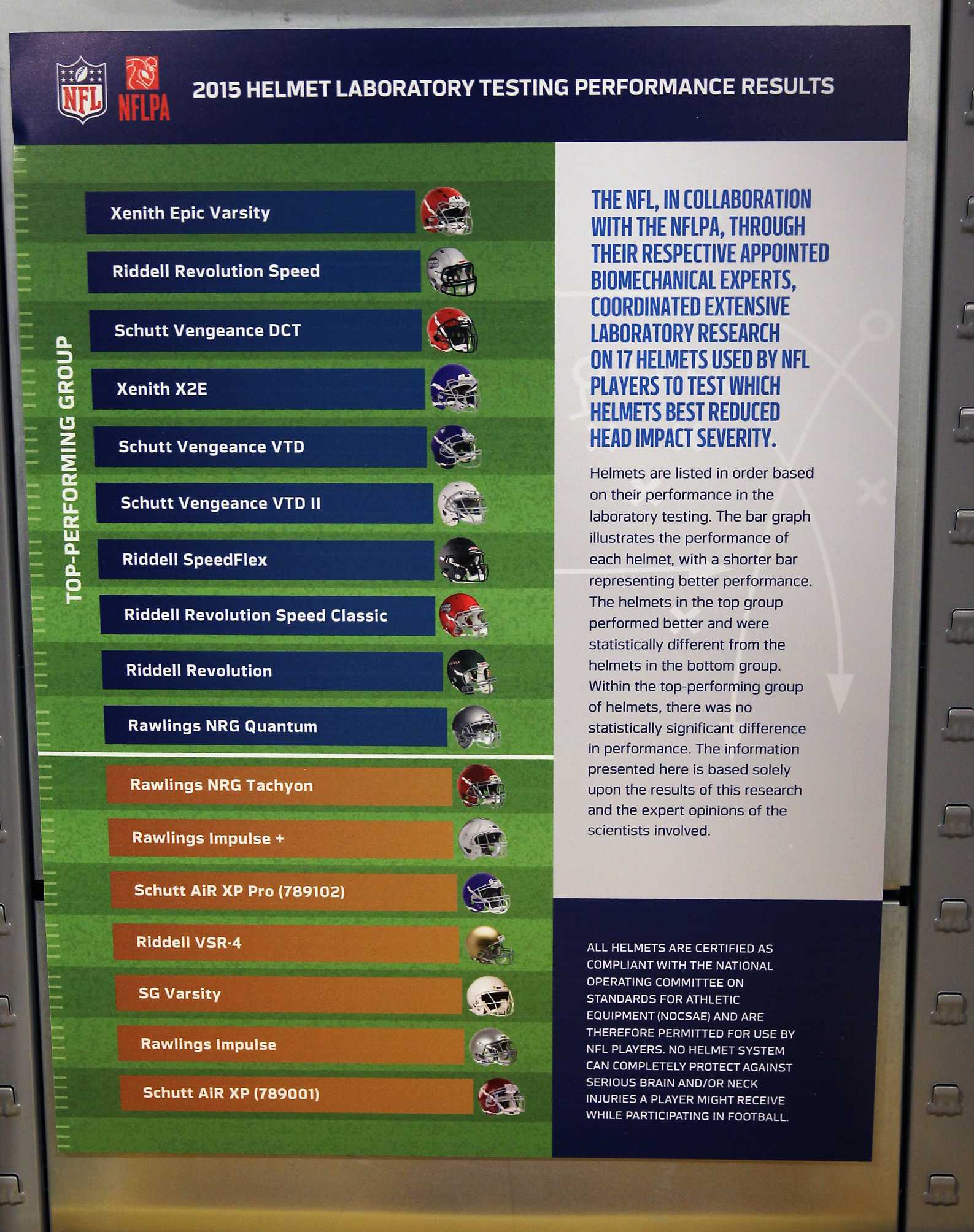

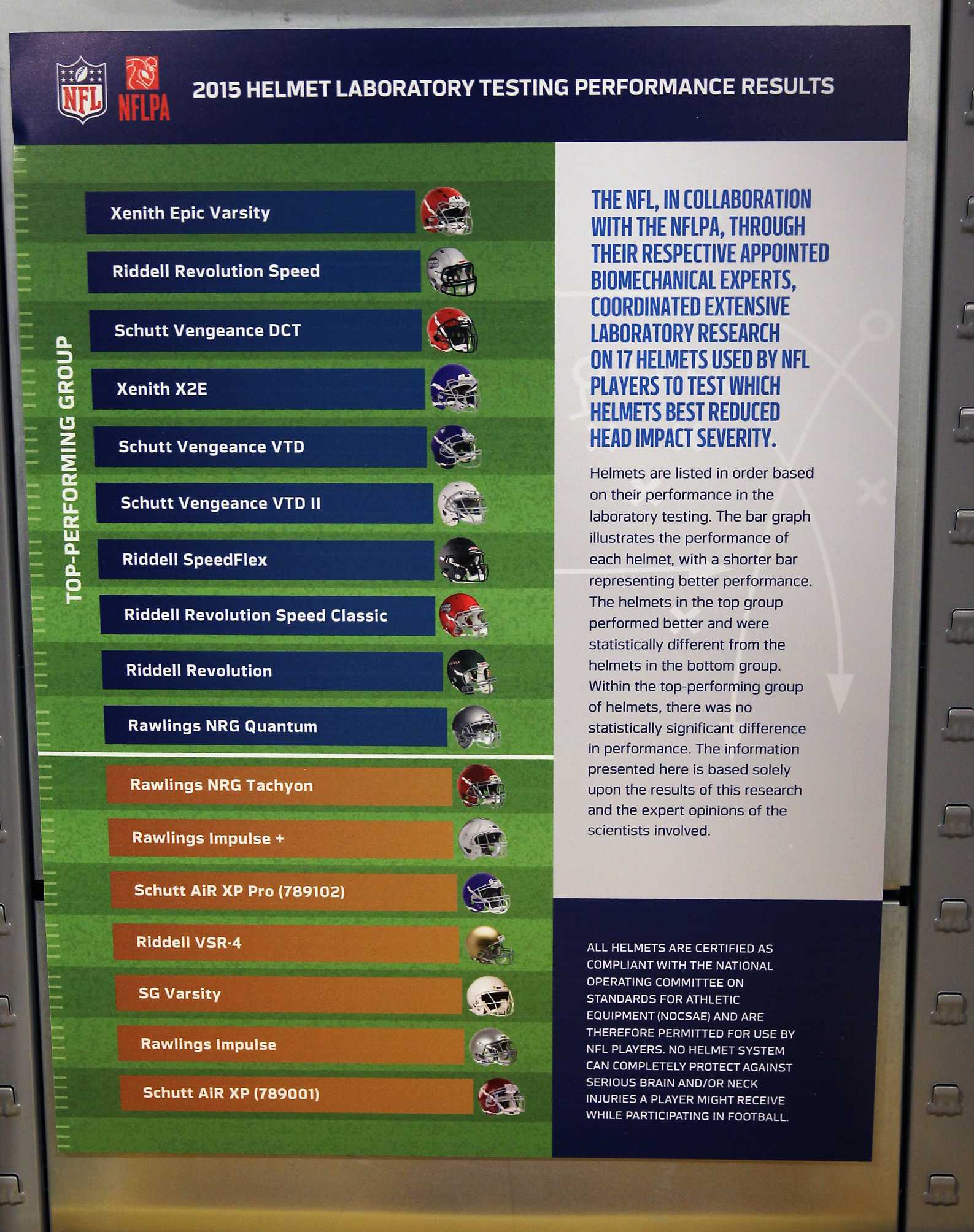

In July the NFL and the NFL Players Association released the results of their own helmet rating system. The NFL’s testing focused on high-impact hits more typical of the professional game. Virginia Tech’s testing is designed to replicate both high- and low-impact hits.

NFL’s helmet safety rating poster in Jets’ locker room (Patrick E. McCarthy)

NFL’s helmet safety rating poster in Jets’ locker room (Patrick E. McCarthy)The NFL/NFLPA listed helmets from best to worst and separated them into two groupings: top performers and low performers. The poster that ranks the helmets says “there was no statistically significant difference in performance” among helmets in the top grouping.

The league’s grouping of helmets was consistent with Virginia Tech’s, aside from a few outliers. But the league says “it is important to emphasize that these results were based on testing intended to represent NFL impacts and thus, the conclusions on helmet performance cannot be extrapolated to collegiate, high school or youth football.”

Unlike NFL players, high school players have little say as to what’s available to them. Either the coach or athletic director purchases the helmets, which range in cost from $150 to $400 each. Some schools said they will allow an athlete to purchase his own helmet if asked. Other schools do not allow it for liability reasons.

NOCSAE, which oversees helmet use in football, recommends but does not require that helmets be reconditioned every year.

Reconditioning is a process in which the padding in the helmets is cleaned and, if needed, replaced, and the helmets are recertified for use by NOCSAE standards. This costs schools about $35 per helmet. Helmets can be reconditioned only up to their original specifications, so a three-star helmet cannot be upgraded to a five-star, Duma said.

Concussion management

New York State’s concussion management act was passed by the legislature in July 2011 and went into effect for the 2012-13 school year. The result of a nationwide push for better standards, the act mandates that any public school athlete suspected of suffering a concussion must be removed from play and cannot return until he or she has written authorization by a licensed physician.

Experts say concussion reporting relies on players speaking up, coaches noticing a violent hit or the athletic trainer recognizing a difference in a player’s behavior. Sometimes there are no immediate symptoms.

Dawn Comstock, an epidemiology professor at the University of Colorado in Denver, has been tracking high school sports injuries, including concussions, on the national level since 2006. She said concussions are the most challenging injury to track.

The incident reports obtained by Newsday offer firsthand accounts of how difficult these injuries are to recognize if the athlete doesn’t speak up.

One player “made a tackle and hit his helmet” in practice and “experienced a headache during and after practice” but did not say anything until the next afternoon. He sat out 21 days before he was cleared to return to play.

One high school reported 11 concussions last season. But in seven of those the incident report notes that the student did not report any symptoms at the time of the injury. Instead, the athlete spoke up either after the game, to his parents at home or to the school’s health office at a later time.

Another player “did not report [injury] at game. Three days later complained of head injury.” Records show he was diagnosed with a concussion and missed 44 days before he was cleared by a physician to play.

Other reports offer a glimpse into the symptoms that occur after a concussion.

One high school player was unable to compete for 38 days. The injury report states, “Coach reports no known hit. Teammates reported athlete appeared confused last 5 minutes of play. Student had no recall of game.”

A report says a player lost consciousness during a game for approximately 15-20 seconds. “When regained consciousness, could not answer questions except ‘yes/no’ squeezing my hand.” The student was cleared to return to athletics 39 days later.

Safety guidelines

A high school football player in a Seattle suburb died of an undisclosed injury on Monday, three days after getting hurt while making a tackle. He is the fourth high school football player to die this season. A player in Louisiana suffered a neck injury, a player in New Jersey died of a lacerated spleen and a player in Oklahoma had a head injury, according to news reports.

At football games, a doctor or medical personnel such as an athletic trainer is recommended to be on hand to assist with injuries, according to the New York State Public High School Athletic Association, the state’s governing body that oversees all aspects of interscholastic sports. But medical presence is not required, NYSPHSAA assistant director Todd Nelson said.

Nassau’s Section VIII, the county’s governing body for interscholastic sports, requires schools to have medical representation “of their choice” on the sideline at all football games. Examples Nassau provides are a doctor, physician assistant, a certified emergency medical technician (EMT), a certified advanced medical technician (AMT) or an athletic trainer certified by the National Athletic Trainers Association.

Suffolk’s Section XI, the county’s governing body for interscholastic sports, follows the state athletic association’s guidelines.

An athletic trainer’s job at a football game is to be on constant lookout for player injuries and be prepared to put the emergency action plan in place in the event of a serious injury, according to Larry Cooper, chair of the National Athletic Trainers Association’s high school athletic trainers committee.

“The way we look at the game is completely different from anybody else,” Cooper said. “We’re looking at the game with an eye on the health and safety of the players.”

At football practices — or any other high school sport practices — there are no state requirements that an athletic trainer be present, Nelson said.

Thomas Dompier, lead epidemiologist at the Indianapolis-based Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention, said Long Island’s concussion figures are likely underreported because of a lack of an athletic trainer at every school.

A study led by Dompier that was published in July in the Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics tracked 96 high schools during the 2012 and 2013 seasons and found an average of five reported concussions per team. Long Island schools averaged 3.5 football concussions during the 2014 season, according to the documents obtained by Newsday.

Dompier said all of the schools that took part in his study had athletic trainers.

New York State’s concussion management act requires that coaches take an online concussion training course every two years. But an athletic trainer has a bachelor’s degree that includes concussion training. “The course that coaches take is just a skimming of the surface” of an athletic trainer’s background in concussion awareness, Cooper said.

Nationwide, 70 percent of public high schools employ an athletic trainer part-time or full-time, according to a study by University of Connecticut researchers published this year.

Schools without an athletic trainer rely on coaches or athletic directors to assess injuries, which the National Athletic Trainers Association said is a disservice to student athletes.

“If coaches do recognize a medical emergency is present, they are not trained to treat potentially life-threatening conditions, nor should it be their responsibility to do so,” NATA said in a statement.

Don Webster, the executive director of Section XI, estimated that 80 percent of Suffolk districts employ a trainer “in some capacity” — full-time or part-time — to assist with all athletics, not just football.

Of Nassau’s 56 districts, 44 employ a trainer in some form, said Michael Spreckels, head trainer for the Seaford district and president of the Section VIII Athletic Trainers’ Society.

Jay Hegi, head football coach in Elmont for 14 years and a coach for 31, remembers only one player ever suffering a concussion, and it was “13 or 14 years ago.” He thinks that’s because they focus on teaching the fundamentals of tackling, they do not hit much in practice and, he said, “a lot of it is luck.”

Hegi said Elmont is one of the eight Nassau high schools that doesn’t have an athletic trainer, which he doesn’t think affects their concussion reporting.

“A coach, if he’s been around the sport, he can tell if a kid is dizzy or not,” Hegi said. “I don’t think a trainer is going to make a difference. Me personally, I can tell. Obviously a trainer is more qualified, but I can tell when a kid is not standing up straight.”

Elmont is one of five high schools in the Sewanhaka district. None employs an athletic trainer, Superintendent Ferrie said. He cited the expense as a factor and estimates that a full-time trainer at all five high schools would cost around $750,000.

“If I didn’t have a budgetary cap placed on me, I would have an athletic trainer,” Ferrie said.

Reaction around Long Island

Long Island school administrators, athletic directors and football coaches ran the gamut in terms of knowledge and opinions regarding Virginia Tech’s ratings.

Plainview JFK athletic director Joseph Braico said the ratings are “definitely a positive” because they give schools guidance on which helmets to consider. He said he’s been using them for three years.

“We try to get only five-star helmets purchased here,” said Braico, a former football player at Division III Westfield State (Mass.). “That’s the transition we’ve been going with. All of our helmets are four or five stars, but anything we’ve purchased over the last three years have only been five stars.”

Not everyone is a believer.

Brentwood athletic director Kevin O’Reilly called it “a very weak survey.” He questioned the methods used by Virginia Tech to test the helmets.

His school has 32 two-star helmets but he said he is not concerned about students wearing them because they have been reconditioned annually and meet the NOCSAE standard to be used during games and practices.

“You can’t be like the pros and get top-of-the-line for everybody under the sun,” O’Reilly said.

“But they are safe and they are meeting the standard set by NOCSAE. . . . What we do here, if they don’t meet the NOCSAE standard, which is the gold standard, then they’re not going to be in play. As long as it’s passing the NOCSAE standard, I’m perfectly fine with it.”

The governing bodies of Suffolk and Nassau sports and the state athletic association do not offer recommendations regarding Virginia Tech’s ratings and allow the school districts to make their own decisions about which helmets to buy.

Of Central Islip’s 62 helmets, 30 are either rated one- or two-star. In a statement, Central Islip Superintendent Craig Carr said every helmet purchased since 2012 has been rated five stars and that the district’s entire inventory gets reconditioned and recertified every year.

The former high school football coaches who now act as the football coordinators for Nassau and Suffolk believe all helmets provide around the same level of concussion protection.

“I believe you can put two good helmets together, no matter what their ratings are, and I don’t think there is any difference,” said Nassau coordinator Pat Pizzarelli, who retired this summer as Lawrence’s athletic director but remains the county’s football coordinator. He said he bases this opinion on conversations with doctors.

He doesn’t believe schools should automatically remove one- and two-star helmets from use as long as they’ve been reconditioned regularly.

Suffolk coordinator Tim Horan questions the Virginia Tech system because he said it doesn’t take the fit of the helmet into account. He said some makes and models fit a player’s head better than another make or model.

Duma said Virginia Tech’s testing assumes a proper fit of the helmet.

“I don’t think in today’s day and age, or right now today, that you can say this five-star helmet is a better helmet than a one- or two-star helmet,” said Horan, who also is the athletic director at West Islip, which has 18 two-star helmets and one one-star helmet (19 percent of its inventory).

But Horan added that he believes in the system enough that since 2011 “we’ve been a lot more conscientious” about purchasing only four- and five-star helmets.

Experts warn there will always be a risk of a concussion regardless of the helmet.

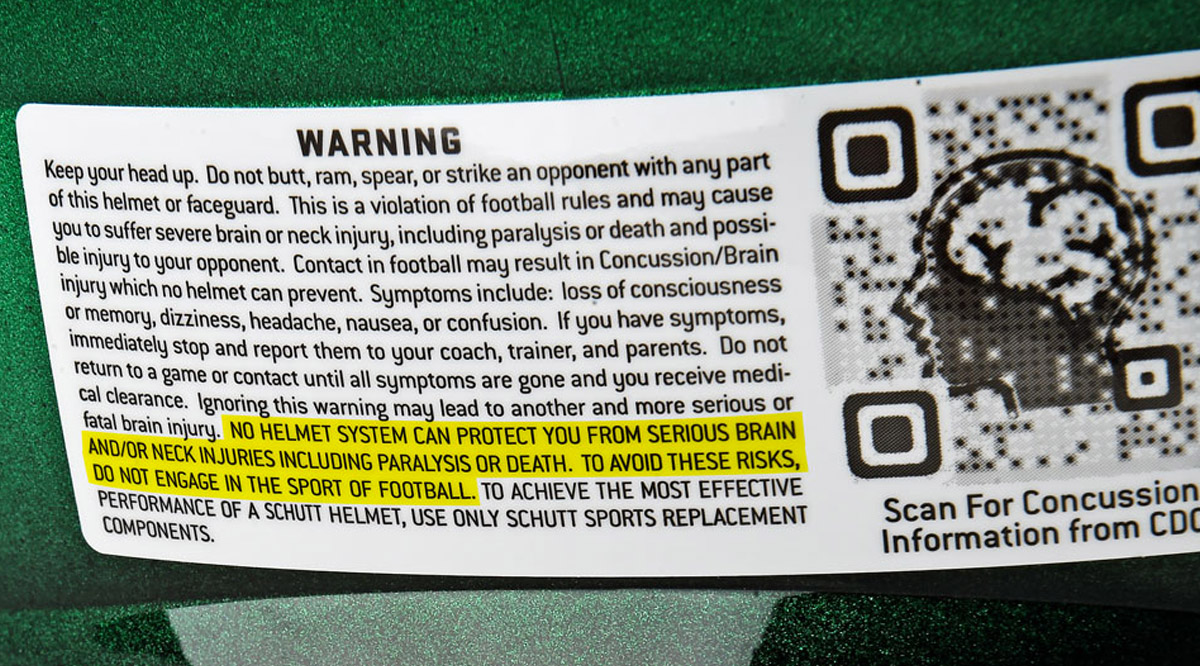

Every football helmet is required to have a warning label that spells out the possibility of danger inherent to the game. Schutt takes its message about the possibility of brain and neck injury, paralysis and death one step further than its competitors.

“To avoid these risks, do not engage in the sport of football.”

NFL’s helmet safety rating poster in Jets’ locker room (Patrick E. McCarthy)

NFL’s helmet safety rating poster in Jets’ locker room (Patrick E. McCarthy)