Map Point Title

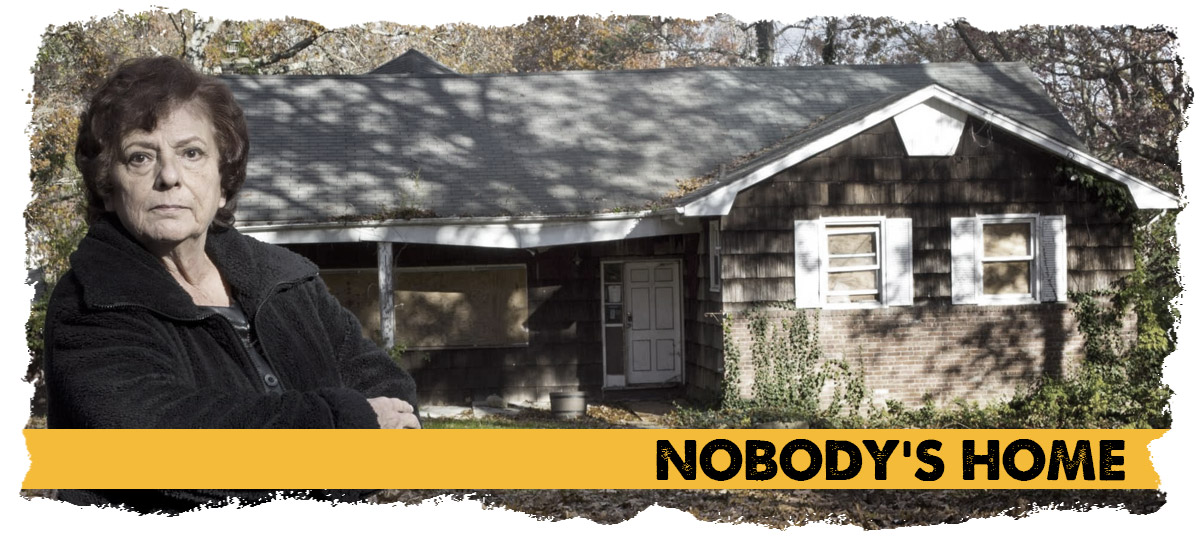

Zombie houses exist in every town on Long Island. Scroll through the gallery to see some of the houses town officials have identified as abandoned homes and watch the map to see how the problem spreads across the island.

Zombie houses exist in every town on Long Island. Scroll through the gallery to see some of the houses town officials have identified as abandoned homes and watch the map to see how the problem spreads across the island.

According to a News 12/Newsday investigation both Nassau and Suffolk lead the state in the number of abandoned or “zombie” homes, costing their neighbors more than $400 million in decreased home values.

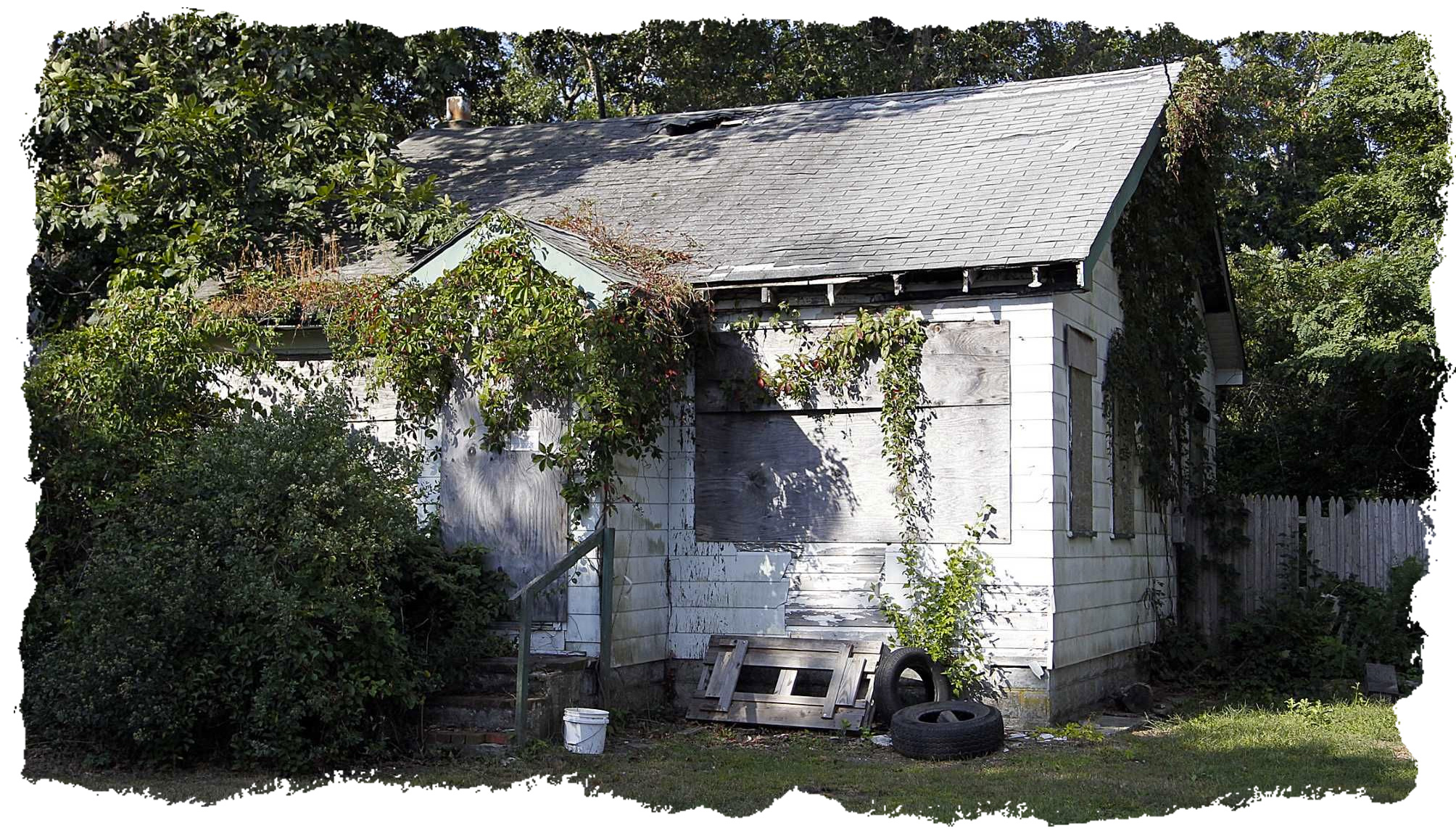

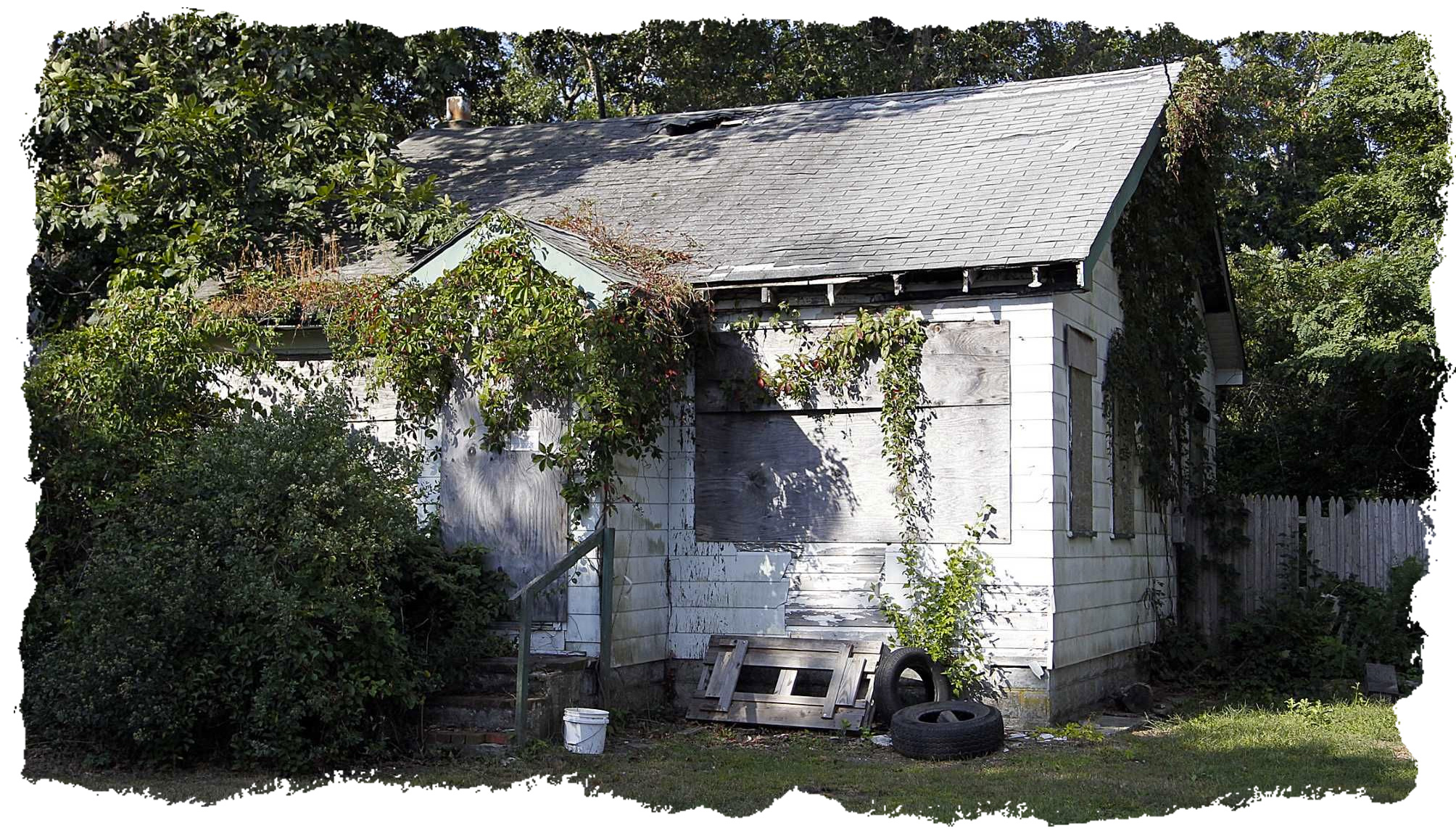

Neighborhoods across Long Island are battling an epidemic of blighted, abandoned houses as municipalities spend millions of tax dollars trying to maintain structures that fester with rats, mold, weeds and squatters.

Long Island communities are littered with empty, neglected homes — from small Cape Cod-style houses in Levittown, America’s first suburb, to large Colonials in upscale Hamptons communities.

The abandoned houses ruin the quality of life for neighbors, threaten public safety and send property values plummeting.

What had been a nuisance in some municipalities intensified with the financial and housing crisis of the late 2000s when thousands of homes went into New York’s nearly three-year-long foreclosure process, creating what have become known as “zombie houses.” Those homes, with no owner on site and no one taking care of the property, are neither alive nor dead.

The size and scope of the abandoned-home scourge is growing so fast that it challenges municipal efforts to keep up with it. The birthplace of suburban life and one of the most expensive places to live in the United States, Long Island now has homes with manicured lawns and meticulously maintained facades sitting side by side with foot-high grass and plywood-covered windows.

And the crisis is worsening.

A yearlong Newsday analysis, using data from municipalities and RealtyTrac, a national real estate tracking company, found:

Long Island “is one of, if not the epicenter of zombie properties in the state of New York,” state Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman told Newsday. “This is a huge problem on Long Island.”

Explore data for your area or others by entering a ZIP code, or click a location on the map.

Bank officials said the homeowner — whether still living on the property or not — is legally responsible for the continued maintenance through the foreclosure process. The financial institutions aren’t responsible because they don’t own the properties until a foreclosure judgment is issued.

But government officials and residents say the financial companies should do more to protect the properties from deteriorating.

In thousands of cases, Long Island municipalities have stepped in to ensure public safety and protect property values, using tax dollars and their own work crews to clean up, board up and tear down deteriorating abandoned houses. Even more employee time is spent trying to find the property owner or the bank to take action.

“This costs our local governments millions and millions of dollars,” said Schneiderman, who in February proposed legislation that would hold banks responsible for the maintenance of empty homes in foreclosure and create a registry of zombie properties in the state. “It’s a problem for local governments and it really is a problem in our efforts to revitalize the New York State housing market.”

As of Jan. 31, there were 182 properties considered zombie houses in the Bay Shore ZIP code, according to data from California-based RealtyTrac, which identifies zombie homes through county foreclosure records and postal service information. Hempstead Village had 170; Brentwood 168; Freeport 142; and Central Islip 139.

Few communities are spared. In Suffolk, Holbrook had 42 zombie homes and East Northport had 27. In Nassau, Westbury had 79, Hicksville 49 and Glen Cove 36. Five are located in the East Hampton ZIP code. Westhampton Beach officials on Thursday demolished the boarded-up, crumbling home of incarcerated former Suffolk Legis. George Guldi. The house had been gutted by fire in 2008 and deteriorating since then.

Officials from the towns with the highest numbers said the problem is far greater than what the narrowly defined RealtyTrac analysis shows.

“The face of Brookhaven has been scarred heavily,” Town Supervisor Edward P. Romaine said. “It’s a legacy that’s going to last for us. . . . It’s beyond the grasp of local government.” Brookhaven spent more than $800,000 cleaning, boarding up or tearing down blighted homes in 2014.

Romaine said there’s “hardly a neighborhood that remains untouched.” But some communities have suffered more than others. North Bellport has 104 vacant or boarded-up houses within 1 square mile, he said.

In Islip, where the town spent more than $200,000 on abandoned homes in 2014, “there has not been a hamlet . . . that has not been affected by this,” said state Sen. Tom Croci (R-Sayville), the former Islip Town supervisor. He described the abandoned-home issue as “the great leveler in our town.”

“We certainly see that there are no social or economic boundaries to this problem,” Hempstead Supervisor Kate Murray said, citing recent teardowns in Bellmore, Merrick and Seaford. “We’ve had demolitions, we’ve had board-ups in probably every single unincorporated area.” In 2014, Hempstead spent more than $700,000 on residential properties that fell into disrepair.

Municipalities undertake work at an abandoned house for a variety of reasons: houses neglected by absentee owners; properties where ownership is in dispute; homes being rehabilitated but the financing ran out; and zombie homes in foreclosure.

Local officials and residents expressed the greatest frustration with zombie houses, blaming banks for the deterioration of the homes and neighborhood property values. Romaine called the lack of bank responsibility “a policy of not even benign neglect, just pure neglect that resulted in the degradation of neighborhoods.”

Representatives of banks and mortgage companies said they try to secure properties and prevent them from becoming eyesores.

“It really doesn’t help us to have a property that’s in disrepair,” said Tyler Smith, real estate owned and community development manager for Wells Fargo in San Francisco. “Eventually, they’re going to complete the foreclosure process and [the home will] become an asset.”

Municipal officials and bank representatives raise concerns about trespassing on private property to take on maintenance work, but the argument rings hollow to those living near abandoned homes.

“All we care about is that this very real problem and this blight on our community and the many blights that exist are addressed,” said Pamela Ubl, 61, of Bay Shore, who has lived near an abandoned home for more than a decade. “We have a right to expect that. I don’t have to tell anybody on Long Island that we pay among the highest taxes in the country.”

Data analysis by Tim Healy

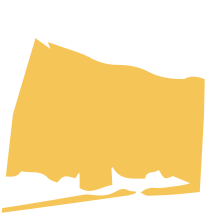

Annette Melchers stands in front of an abandoned house next to her home in Dix Hills. (Photo credit: Newsday / Chuck Fadely)

Karen Newman started noticing houses in her Levittown neighborhood with large red squares posted on them in early 2014.

Some signs included an X or a slash through them. They reminded Newman, 50, a retired NYPD crime scene photographer, of signs warning emergency responders about unsafe homes in the city. The postings in Levittown by Hempstead Town officials serve the same purpose — identifying abandoned, neglected properties that have deteriorated to the point of being unsafe.

Newman started taking photos of neglected homes, posting them on a Facebook page she created called “The Levittown Project.” She has more than 60 vacant houses on the site.

Levittown, created in the late 1940s as America’s first suburb with tidy houses and yards for growing postwar families, is home to 81 zombie houses, according to RealtyTrac, a California firm that tracks the homes that are in the foreclosure process but abandoned. The number in Levittown is the seventh highest among 67 Nassau County ZIP codes.

Newman, a 16-year resident, said that “never in a million years” would she have imagined there would be so many abandoned homes in Levittown. “If you had told me that there would be [safety warning] signs outside houses that have been abandoned, I never would have believed it.”

The impact from neglected homes spreads beyond property lines. From scurrying rats and marauding raccoons to the stench of garbage and mold, the quality of neighborhood life is compromised. And the longer the house is abandoned, the worse the problem gets.

“When you see a rat that’s the size of a cat on your property, you get scared,” said Ora Scheine, 63. She and her husband, Ed, 65, have lived next to a boarded-up house in Dix Hills for seven years. There’s a hole in the roof and a tree growing through the chimney. Raccoons frequently roam onto the Scheines’ property and knock down their trash pails. “Every day I’m cleaning up garbage on the driveway,” she said.

Porzia DiGiorgio, 42, and her husband, John, 44, live on the same cul-de-sac as the Scheines. “You can’t even have a friend drive down the street and not make assumptions about your neighborhood,” John DiGiorgio said.

Douglas Bunge, 66, said the abandoned home on his Bay Shore block has broken windows and graffiti as well as construction debris and a boat rotting in the backyard — across the street from an elementary school.

“Lately it has become a real hangout at night for the kids,” he said of the empty house. “Somebody could very easily get hurt, there’s so much debris over there.”

And if someone does get hurt in a crumbling, abandoned house, first responders may be limited in what they can do.

“When a kid roams in to explore and falls through to the basement and gets hurt, how do we get in there?” said Mastic Beach Fire Marshal Carlo Grover. Abandoned homes “are a safety issue and definitely a concern.”

Once a month, Grover drives around the village looking for unsafe, abandoned houses that had been reported by residents. He surveys the home from the outside, checking for decaying wood or holes in the roof. Then he peeks through the windows looking for squatters as well as animals, rodents or anything else that could pose a safety threat. Next, he slowly enters while tapping a pole to test the stability of the floor ahead of him.

“If it looks too dangerous, we don’t go in,” he said. “These abandoned homes aren’t just a risk to the public, they are a risk to the department.”

Insp. Gerard Gigante, Suffolk Police First Precinct commanding officer, said squatters in abandoned homes often remove valuable copper pipes, causing flooding. Propane tanks and barbecue grills are brought inside for heat and create a fire hazard. He cited one home where stairs had been removed and another where the toilet flushed directly into the basement because the plumbing had been disconnected.

Abandoned homes that sit vacant for months or years can bring another menace to neighborhoods: mold.

“It’s a quality-of-life issue for every single neighbor who walks by that house, lives next door to that house, leaves their window open . . . it’s a problem in your house then,” said Terence McSweeney, a North Babylon civic leader who estimates that a 10th of his community’s homes are abandoned.

“It’s extremely frustrating,” he said. “I grew up in this neighborhood. There was never a vacant house. Last year we had dozens.”

Central Islip homeowner Mauricio Turcios, 35, said his community has so many abandoned homes that he doesn’t allow his children to play outside. “The bus picks them up and drops them off and that’s it,” he said, noting that the empty houses have attracted squatters.

Residents who live near abandoned houses said they’ve spent years calling and sending letters to every official and agency they can find — all the way up to the federal level. They have tried to track down banks and property owners. But the efforts have amounted to nothing, they said, as the homes and their quality of life decay.

“The great frustration is that every single agency, every entity we’ve talked to . . . no one can give us any information as to how this can be resolved, when it will be resolved, if it will be resolved,” said Pamela Ubl, 61, who has lived near an abandoned home for more than a decade in Bay Shore.

Blame usually first falls on town and village officials, even as those leaders explain to residents that private property laws limit what they can do.

“If our elected officials ultimately are saying they can do nothing, then where do you go?” Ubl said. “Even though we get great expressions of sympathy from our elected officials and the banks involved, we don’t want to hear that anymore. We want it resolved.”

In Mastic Beach, where the mayor estimates there are hundreds of abandoned homes, residents have tried to rein in the neglect by cutting grass and trimming trees on blighted properties themselves.

In Islip Town, which has three of the ZIP codes with the highest numbers of zombie homes in New York, state Sen. Tom Croci (R-Sayville), the former town supervisor, said the quality-of-life issues brought to officials about abandoned houses “have been overwhelming.”

Hempstead Supervisor Kate Murray said it frustrates her as much as any resident to see a house fall into disrepair. “Because the bottom line is we want to help our constituents and want to make sure our neighborhoods stay as beautiful as they can,” she said.

Newman said that if anyone visits her Levittown home, no matter which direction they come from, they will see blight — from shattered windows to tattered porch screens and padlocked doors. “It’s just sad because on my block, it’s a really beautiful block,” she said. “Now looking forward you have to figure, how much is that devaluing my house?”

Annette Melchers, 69, got the answer to that question when she tried to sell her Dix Hills house and buyers were deterred by the property next door — the same eyesore that worries the Scheines and DiGiorgios.

Melchers has owned her home for 40 years and lives with her two adult disabled sons, she said. She retired from her job as a nurse practitioner at Sagamore Children’s Psychiatric Center three years ago and wants to move to Florida. In 2013 she put her home, appraised at $695,000, on the market.

“The house is terrific, the house is priced right and I get calls on it constantly,” said Melchers’ real estate agent, Sheila Gatto of Realty Connect USA in Woodbury. “But the minute anyone comes, they look next door to that blighted house and they’re afraid.”

Gatto said she took about 60 to 70 people to see Melchers’ house. Some took one look at the boarded-up home next door and turned right around, she said.

“You can’t say to them well maybe the house will be torn down, maybe this, maybe that,” Gatto said. “Especially when someone is spending a half-million dollars.”

A prospective buyer offered Melchers $550,000 and she was inclined to accept the offer. But he came back with his wife, who refused to even step inside the home.

“I couldn’t give this house away because of that house next door,” Melchers said. “I feel trapped.”

Neighborhood residents said the blighted house is “beyond repair” and all of the copper piping has been ripped out. Even though the home has been boarded up, the front door is unlocked and can be pushed open, requiring constant vigilance by neighbors to ensure no one illegally moves in.

Huntington Town spokesman A.J. Carter said an engineer inspected the house in December. He recommended in his report that it be demolished, noting that it contains a “hazardous environment” of moisture and mold, and recommending the town “clean the concrete foundation walls and slab, and fence-in the concrete foundation for the safety of the public.” An administrative hearing on the demolition is scheduled for next month, Carter said.

State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman called residents like Melchers “the worst victims” of the zombie home crisis.

“If you work hard and you’re working multiple jobs, you manage to save your home after the collapse of the housing market and you’re staying current on your mortgage but you’ve got two abandoned properties around you . . . your opportunity to sell the home and move on is hurt, the property values go down,” he said. “It’s well documented that crime and vandalism go up. So it brings down a whole community.”

Dilapidated abandoned homes have cost Long Island at least $295 million in depreciated home values, according to an analysis of RealtyTrac’s zombie home data by Manhattan-based appraisal firm Miller Samuel. Vacant homes are likely to suffer an average price reduction of roughly 20 percent and the five closest neighbors face a price cut of about 5 percent, estimated company chief executive Jonathan Miller, who analyzed the data for Newsday.

Town and village officials said banks could prevent the loss in property values by maintaining an empty home while it is in the foreclosure process.

“If you just put a little money into this house, it would sell for more, it would sell for the asking price in the neighborhood,” said Shanna Smith, president and chief executive of the Washington, D.C.-based National Fair Housing Alliance, a consortium of groups focused on ending housing discrimination. Instead, financial institutions “are pulling down the property values and as a result if you live in that neighborhood you can’t refinance because you have a hard time . . . getting a line of credit, or your line of credit may be reduced,” Smith said.

Those who live near blighted homes lament the lost promise of suburban life that had enticed families to move to Long Island.

“The suburbs have traditionally represented and been emblematic of the American dream,” Ubl said. “This is where people came to start their lives and have their children and enjoy a quality of life that they associated with being a middle-class American or a working-class American and to have that undermined . . . I think a lot of people are deeply frustrated and confused and feeling very powerless.”

Zombie houses exist in every town on Long Island. Scroll through the gallery to see some of the houses town officials have identified as abandoned and watch the map to see how the problem spreads across the island.

west nassau

east nassau

west suffolk

central suffolk

east suffolk

Ed Gay Sr. sees plywood-covered windows and doors in every direction when he steps onto his front porch.

There are boarded-up houses on either side of his neatly maintained Wyandanch home, two more across the street and another two within view down the block. Surrounded by blight, Gay’s neighborhood has become a microcosm of Long Island’s growing struggle with neglected, abandoned houses.

“I’m very frustrated,” he said. “It’s just a mess.”

Gay, 77, a retired head bus mechanic, said the deteriorating homes on his street have been problems for years. He said men wielded shotguns and machetes at one abandoned house and squatters nearly burned down another. On either side of his house there always seems to be loud music and cursing, and a steady stream of people coming and going from the homes.

On a recent day, the sheet of plywood covering the front door of a home next door blew open. A hole just below a window facing Gay’s house has become another entry into the structure.

“You name it, every kind of animal has been in there — raccoons, squirrels, everything,” he said. “I can’t even sit in my bedroom without seeing that hole.”

Gay, a Korean War veteran, bought his house 43 years ago and still remembers the names of all his original neighbors. Back then, kids played in the street, he said. There were weekend block parties where police, after cordoning off the road, stopped by for barbecue. Neighbors took meticulous care of their lawns in the summer and offered to help shovel driveways of the elderly in the winter.

“It makes me very angry, what’s happening now,” he said.

Gay, who lives with his wife, Josephine, 71, and granddaughter Shakima, 21, said he keeps watch on the abandoned homes near him, patrolling every night as he walks his dog. He regularly cuts the grass and rakes the lawns of the houses on either side of his.

“Everybody calls me a damn fool because they see me doing it and wonder why,” he said. “I do it because I love my house.”

Gay said he’s constantly calling police or Babylon Town, looking for help. “Somebody’s always breaking into the house next door,” he said. “I call 911. It just keeps happening.”

Suffolk police said there have been many calls about squatters or related issues on the block, and a Babylon Town 14-page incident report on one of the properties next to Gay’s goes back nearly a decade.

The town has cleaned or boarded up at least six properties on the street. Workers tried without success to get banks to maintain the properties in foreclosure, officials said.

“Have exhausted all avenues of getting a hold of bank,” a town worker wrote in the incident report in 2012. “Spoke with several people, they were supposed to have the preservation department get back to me. I again have left several messages to no avail. Also tried getting numbers for the preservation department myself, have not had any luck.”

Gay said many of the homes on the street began to deteriorate after their original owners died or relocated, leaving the homes to their children. Unable to keep up with property taxes, they began renting them or abandoning them, he said.

During the height of the crack epidemic in the ’90s, Gay said, he considered moving out of Wyandanch, even though he raised five children there.

Instead of moving after retiring, he expanded and updated the house, adding two bedrooms and a front porch. The work increased the value of his home significantly, Gay said.

But after an assessment last year, Gay said, he learned the proliferation of abandoned houses in the neighborhood decreased the assessed value of his home from $72,000 to $58,000. The assessor, he said, told him it’s a “neighborhood that nobody wants.”

Even so, he won’t sell. He proudly points to the 30-year-old rosebush he cares for in the summer, along with a garden full of collard greens, tomatoes and carrots.

“I love my house,” Gay said.

His son Ed Gay Jr. said many people in the neighborhood simply want to live a quiet suburban life.

“We don’t want loud noise or neighbors who park cars on their lawn,” he said. “The same things people in Oakdale want, the same things people in the Hamptons want, the people in Wyandanch want.”

What Gay Sr. wants, he said, is for his block to be “nice again.”

“I’m looking for someone to move into those houses who wants a home,” he said. “I just hope I’m around to see it.”

Paul Degen, chief investigator in the Brookhaven town attorney’s office, takes a photo of an abandoned houses. (Photo credit: Newsday / Chuck Fadely)

Maintaining abandoned, neglected, crumbling homes is a time-consuming and costly business for Long Island municipalities.

Officials said the number of decaying properties began to rise sharply after the housing crisis took hold in 2007 — and it’s only gotten worse.

“There are more houses than I’ve ever seen before . . . more homes that are being neglected,” Hempstead Supervisor Kate Murray said.

A yearlong Newsday analysis found that towns and villages across Long Island last year spent at least $3.2 million to clean, board up and demolish thousands of neglected homes. Most of the blighted properties are what have become known as “zombie houses” — homes that are being foreclosed on by financial institutions and the owner has walked away.

Town and village workers try to track down the financial institutions involved and then push them to tend to the properties. Bank representatives, however, say that without holding title to the property, they are limited in what they can do.

“What was an occasional problem here and there at the turn of the century has become a pervasive problem,” said Brookhaven Town Supervisor Edward P. Romaine, who estimates there are about 2,000 vacant and blighted homes in the town.

The total number of abandoned houses on Long Island is difficult to calculate, officials said, especially after superstorm Sandy in 2012 left many homes at least temporarily empty. Municipalities often have different definitions of what constitutes an abandoned home and don’t keep a separate count of zombie properties.

But Long Island officials agree the number is in the thousands — and much higher than statistics indicate.

California-based RealtyTrac, which compiles real estate data, identified 4,044 zombie homes in Nassau and Suffolk — nearly 24 percent of the state’s total of 16,777 — as of Jan. 31. RealtyTrac’s methodology focuses on active foreclosures and automatically removes any home that is still in the process beyond the state’s average foreclosure time, which in New York is 934 days.

However, residents and local officials point to properties that have been stuck in the state court’s foreclosure process for five years or more, homes that they said would be missing from RealtyTrac’s data.

The longer the houses sit empty, the more problems develop.

Municipal workers are largely limited to outside cosmetic improvements, such as mowing lawns, trimming bushes and removing trash.

“We’re eliminating all the visible immediate problems so the house remains stable and that will make the neighborhood stable,” said Lindenhurst Village Clerk-Treasurer Shawn Cullinane.

Abandoned homes that are not secure — and easily accessed by children and squatters — can be boarded up. And if an engineer determines a house is structurally unsafe, state law allows municipalities to demolish it.

“We have a responsibility to try to board them up, cut the grass, maintain them,” said Valley Stream Mayor Edwin Fare. “You’re trying to protect the integrity of the village, the suburban community we live in, but we have to follow the law. We just can’t arbitrarily say ‘their grass is high’ and go on their property and cut their lawn.”

Town and village board members each month vote to approve dozens of resolutions authorizing clean-ups, board-ups and demolitions. They then seek to recover money spent by adding the costs to the abandoned property owner’s tax bill.

With foreclosures, the tax bills are paid by the bank. If left unpaid, the county could seize the property. Officials said they eventually recoup the money but getting those funds repaid can take more than a year.

“Any time you have to lay out that kind of money, it is something that we shouldn’t have to do,” said Babylon Town Supervisor Rich Schaffer. “But I view it as an investment in our communities in that it’s important that we make sure we’re keeping these properties secure, safe, cleaned up.” The town spent more than $900,000 on blighted properties in 2014.

Romaine said it takes at least 18 months for Brookhaven to recoup clean-up costs through the additional tax payments. The town does not get reimbursed for “hidden costs,” such as legal expenses incurred by town attorneys attempting to locate owners of derelict homes.

“We could be cutting down our expenses or using them in other ways,” Romaine said of the money spent on abandoned homes.

The town does not have enough money to tear down all houses that should be demolished, Romaine said. Mortgage tax revenue from property sales in Brookhaven have declined to about $9 million to $10 million per year from about $36 million annually a few years ago.

Officials also struggle with using municipal work crews to maintain vacant homes.

“Our staff could be addressing a lot of other issues but because of the number of [abandoned] homes, that staff time has been diverted,” Schaffer said.

Ed Buturla, lead inspector with Babylon’s environmental control department, said his workers try to keep tabs on the homes they know have had problems, but the numbers have become too great. “We do patrols, but we only have so much manpower to use,” he said.

For villages, with smaller budgets and fewer employees than town governments, the work needed to address blighted homes can become cost prohibitive.

“It’s something we shouldn’t have to deal with, and it’s something we have to put our resources in,” said Hempstead Village Mayor Wayne J. Hall Sr. “If we can get the banks to do their part . . . that would take a lot off of our village.” Hempstead spent about $100,000 on neglected homes last year.

Mastic Beach Village incorporated in 2010 partly in an attempt to crack down on code violations and absentee owners. “One reason I voted for Mastic Beach to become a village was to get problems like this done quick, but that hasn’t been the case,” said Brenda Richardson, 55, who lives across the street from an abandoned home gutted by fire. “We keep hearing from the village that it’s going to be torn down, but we keep getting disappointed because nothing happens.”

There are about 250 abandoned homes in the village, Mayor Bill Biondi said, and officials are trying to keep up.

“This is great what we’re doing,” he said of village efforts to maintain the neglected homes. “But what kind of long-term effects does it have?”

Municipal officials said that in cases where a bank is involved, they are as aggravated as the residents.

“I get professionally frustrated as well as personally frustrated because I live here too,” said Babylon Town Supervisor Schaffer.

Despite the strain, the money and staff time must be spent, officials said.

Residents “want to be able to say they have a certain quality of life, they want to protect the value of their homes,” Cullinane of Lindenhurst said. “So if we do not help eradicate this problem of . . . homes that are unkempt, then the entire thing will spread to surrounding houses and whole neighborhoods will be affected.”

It usually starts with a phone call.

A resident complains to town or village officials about conditions at an abandoned house, and the process of battling weeds, rodents or worse begins.

Municipalities undertake work on an abandoned property for a variety of reasons: houses neglected by absentee owners; properties where ownership is in dispute among family members; homes that are being rehabbed but financing runs out; and zombie homes that are being foreclosed on.

Properties are generally inspected within a week or two of a complaint, officials said.

“Although we can correct the condition in five to seven days, that’s a long time if someone is having a family party and somebody has ripped the door off the home next door,” Freeport Village Mayor Robert Kennedy said. The village spent nearly $200,000 on blighted homes last year.

Babylon Town Chief of Staff Ronald Kluesener said the problems uncovered in inspections range from the annoying to the dangerous.

“Maybe there are kids going in there, maybe there are illegal activities taking place, maybe there are animals, maybe there are raccoons living there, or rats, maybe there’s tall grass, maybe there’s debris, maybe there’s a collapsed septic tank, maybe there’s all of those things,” he said.

Life Cycle of a Zombie House

Life Cycle of a Zombie HouseThe process of taking care of a zombie house can take years, and it often starts with a phone call from residents complaining about an issue they’ve spotted at an abandoned property – overgrown grass, broken windows, piles of trash. After that, it’s up to the town to track down the responsible party or address the problem. Often it’s a mix of the two, costing the town in both dollars and manpower.

Click through this interactive timeline to see real examples of how officials in the Town of Babylon addressed one zombie house and how much it cost. Note that although the town will front the cost of maintenance, officials expect to add that cost to the property’s tax bill.

The first complaint on file for this house was May 8, 2007. This is a truncated version of the complaint log.

Before they spend time and money to fix the mess, town and village workers check with the county clerk’s office to find the last owner of record who would be responsible for repairs.

“If we actually have a homeowner who gets on the line and says ‘I’ve had x, y and z problems and if you could give me a couple more days’ … dollars to doughnuts we’ll do that,” Hempstead Town Supervisor Kate Murray said. “The bottom line is we want compliance and if the homeowner can do it themselves, it’s better for us too.

“We don’t want to be in the rehab business,” Murray said. “We don’t want to be in the landscaping business either, quite frankly.”

The trouble starts when municipal officials learn a home is in foreclosure and the owner has walked away, leaving a zombie house behind. Until the foreclosure process is completed, the owner remains liable for the maintenance.

But with a homeowner no longer on site, municipalities turn to banks. And finding the right financial institution to take responsibility isn’t easy.

“You have a bank in Texas, a mortgage company in Wisconsin, an attorney in New Jersey, an owner who is in Florida, who is dead or who we can’t find, and then we have a home here in Valley Stream,” said Edwin Fare, the village mayor.

Zahra Jafri, president of the Empire State Mortgage Bankers Association and owner of Lynx Mortgage Bank LLC in Westbury, described the zombie house crisis as a “very difficult situation,” but said it’s “up to the municipalities and community services to perhaps come up with some sort of method to report homes that look like they are in disarray.”

Valley Stream Clerk and former Assemb. Robert Barra said the calls needed for just a handful of homes take up 70 percent of his time as clerk.

“It was impossible to get to them,” Barra said of his attempts to reach Nationstar Mortgage Holdings Inc. about a property it was foreclosing on. “I called everybody. Press one, press two. And then just when you thought you were going to get to speak to a person, it says ‘please type in your Social Security number.’ “

Then he tried to reach CitiMortgage, a division of Citigroup, about another property. “You were literally ripping your hair out because the way the corporate veil was set up, it was made to keep you away,” he said.

Barra said that because of those frustrations, the village does not invest any money with Citigroup or any of its subsidiaries. “It just flies in the face of every resident if we do that,” he said. Hempstead Mayor Wayne J. Hall Sr. said his village took a similar tactic with Chase.

Newsday reporters contacted banks with similar results. A Nationstar spokesman was reached only after the same effort that Valley Stream officials faced. A bank spokesman said the company has a “dedicated property preservation department that coordinates and has oversight for all properties” and that there is a contact number listed on all homes.

A Citigroup spokesman declined to answer specific questions about abandoned homes.

Financial companies affiliated with an address may only serve as a “trustee,” accepting mortgage payments and sending them to investors who bought a group of loans that include that property’s mortgage. Those companies typically say they have no direct responsibility for the property because they have hired another company to service the loan. Mortgages are often sold from one entity to another over the course of a foreclosure, and banks sometimes fail to register those transactions with county real estate offices.

“They’ll change banks and no one will know about it and we’ll find out by accident,” Barra said.

Even when a municipality finds the right person at a bank, it becomes “a game of telephone tag” because “the sense of urgency isn’t the same for the bank as it is for the town,” said state Sen. Tom Croci (R-Sayville), the former Islip supervisor.

Valley Stream officials finally sent summonses to the attention of bank chief executives at their corporate headquarters. After that, they started getting responses, Barra said.

But Valley Stream Justice Robert Bogle, who handles village summonses that are given to banks and homeowners and also reviews foreclosure cases as a supervising court attorney in Nassau County Court, said the financial industry was unprepared for the zombie house crisis. “The banks are overwhelmed because they’re not in the real estate business,” he said. “They never expected something like this to happen.”

Municipal officials said some banks are responsive and take care of their properties without prompting. Others take some action but not enough.

“They’ll cut the lawn, they’ll board it up,” Barra said. “And they’ll try to leave it like that until the people complain enough and they have to go back and cut the lawn again or we cut the lawn and put it on the tax bill.”

With Deon J. Hampton

An abandoned house in Brentwood is shown Thursday, Dec. 18, 2014. (Photo credit: Newsday / Chuck Fadely)

Responsibility for Long Island’s exploding abandoned house problem is being placed mainly on the financial institutions seeking foreclosures on thousands of properties caught up in the financial crisis of the late 2000s.

When the homeowner walks away, towns and villages look to banks that issued the mortgages to maintain properties, but the financial companies have no legal obligation to do so. As a result, the properties, known as zombie houses, fall into a gray area that often leads to disrepair.

New York’s judicial foreclosure process averages 934 days, leaving many houses vacant for years, slowly decaying and cultivating infestations that range from mold to rats. The problems spread to nearby homes and ultimately drive down property values for entire neighborhoods.

A yearlong Newsday analysis found that with no one maintaining the properties, municipalities had to spend at least $3.2 million in 2014 to clean, board up and demolish thousands of abandoned homes.

Municipal leaders said it’s simply not fair for banks to place the burden of property upkeep on local governments.

“Our goal is not for us to be maintaining properties but for banks to be taking some social responsibility in our neighborhoods,” said Babylon Town Deputy Supervisor Tony Martinez.

Source: RealtyTrac

Representatives of banks and mortgage companies said the blame for zombie homes is misplaced and the problem lies with the state’s lengthy foreclosure process. Zahra Jafri, president of the Empire State Mortgage Bankers Association and owner of Lynx Mortgage Bank LLC in Westbury, said the issue boils down to the lender not wanting to spend money “to maintain a home that is not theirs.”

“I feel that if someone is to buy a home and take a mortgage out, they should be responsible for maintaining that home,” Jafri said. “Lenders do not own the home. I see a fundamental disconnect with who has the responsibility to maintain that property.”

Newsday tried to contact more than three dozen homeowners who abandoned properties in foreclosure but they could not be reached, did not return phone calls or declined to be interviewed.

The zombie house epidemic was years in the making, tied to the housing crisis that was fueled by high-risk loans that led to record foreclosures. During the boom years of the early 2000s, lenders scrambled to make loans that they could repackage and sell to investors under what the U.S. Justice Department has said were careless or sometimes deceptive practices.

Years later, the housing crisis had seeped into all income levels across Long Island. Median home prices, not counting the East End, plummeted by 23 percent to a low of $339,000 in late 2011 from their peak of $442,380 in fall 2007, according to data from the Manhattan appraisal firm Miller Samuel.

“We’ve known the tsunami was coming,” said Martinez. “We’ve known that it was just a matter of time before all of these homes would be in our neighborhoods.”

Foreclosures are declining across the country, but the numbers continue to rise in New York. The state had 47,612 foreclosure filings on record last year, a 39 percent increase from two years ago, according to California-based RealtyTrac, which compiles real estate data.

New York’s average foreclosure time is down about 100 days from a year ago, but remains the fourth-longest in the country, said RealtyTrac vice president Daren Blomquist. The lengthy process is linked to state law requiring a lender to sue to take back a home. In other states such as Texas where lenders do not need court approval to foreclose, the process can take as little as three months, according to RealtyTrac.

“I think the foreclosure process was extended in a well-intentioned but perhaps not very effective effort to provide additional protections for homeowners,” New York State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman said. “In fact, what it’s ended up doing is penalizing both sides because it drags on and on.”

The length of time needed for a foreclosure to work through the New York judicial system increases the possibility that a homeowner will walk away, Blomquist said.

Valley Stream Village clerk Robert Barra said banks need to find a better way to manage the long process. “They can’t just point to the courts and say ‘well it’s in the court for three years and so you have to live near a boarded-up house with raccoons in the chimney.'”

Bank officials said they encourage homeowners to remain in the home and maintain it during foreclosure.

“We do try to have that conversation with them,” Tyler Smith, real estate owned and community development manager for Wells Fargo in San Francisco, said of homeowners facing foreclosure. “We don’t want to take the property back. If it’s not good for the customer, if it’s not good for the neighborhood, it’s not good for us.”

State law had only required banks to be responsible for maintenance once they took ownership of a home. That changed in 2010 when a new law forced banks to take on that duty as soon as a court issues a judgment of foreclosure, which allows them to eventually take ownership, said Bruce Bergman, a Garden City-based attorney who represents banks.

Municipal leaders said they feel the most frustration in that period before the bank takes possession.

“If the house is in foreclosure, and the bank doesn’t really own it, we’re in limbo there,” Hempstead Village Mayor Wayne J. Hall Sr. said.

Federal Department of Housing and Urban Development regulations require companies that own or guarantee mortgages, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, to have their “servicers” perform basic maintenance on a home in the foreclosure process. Those servicers — often large banks such as Chase or Bank of America — hire national property preservation companies to oversee maintenance. The property preservation company then hires local contractors to perform work such as mowing the lawn and removing trash.

When homeowners sign mortgage documents, they agree to maintain the home and are held legally responsible for it, Bergman said. But the mortgage documents also give the lender or the servicer it hires the right, if it chooses, to secure the home if its value is in danger of eroding. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which hold or guarantee roughly half of all mortgages, require servicers to secure properties within seven days of learning they are vacant. The servicer must change the lock, check for damages, do necessary work to preserve the property and post contact information for the servicer or vendor, according to Fannie Mae’s guidelines for servicers.

A lender only has a lien on the home, not an ownership interest, and it does not make sense to impose the responsibilities of ownership without the rights, Bergman said.

“Winterizing the premises they typically will do because the effect on value is very significant,” he said. “As for mowing the lawn, they will often do that just to maintain the value of the property. But if they choose not to, it’s a business decision on their part.”

And lenders often decide not to invest money in a property they do not own, Jafri said.

“In most cases they are maintaining the taxes and insurance and then to also expect a lender to maintain the property, I think that’s quite expensive for a lender,” said Jafri, whose company has about 400 mortgage customers.

According to RealtyTrac, the top 10 leading lenders for zombie properties on Long Island are Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Chase, Citigroup, HSBC, Deutsche Bank, U.S. Bank, Nationstar Mortgage, OneWest Bank and Bank of NY Mellon.

Citigroup, OneWest Bank and HSBC declined to answer specific questions about their property preservation practices. U.S. Bank, Deutsche Bank and Bank of New York Mellon representatives said they only oversee mortgages on Long Island properties as trustees and do not service them.

But trustees of homes that become part of their inventories can be held responsible for property maintenance. In 2013, Deutsche Bank settled for $10 million with the city of Los Angeles after being sued over its failure as trustee to maintain their real-estate-owned properties — those that have been through the foreclosure process with the banks taking title — in minority communities.

The Washington D.C.-based National Fair Housing Alliance has sued some banks, alleging that they routinely allow homes in minority communities to decay while maintaining homes in less diverse neighborhoods.

Municipal leaders on Long Island reported that some minority and working-class communities were the ones hardest hit by the housing crisis and have become home to the largest numbers of zombie properties. Babylon’s Martinez said his town, as a largely blue-collar area, has felt the impact.

“Usually banks take better care of properties in high-class communities than in working class communities,” he said.

Chase spokesman Jason Lobo wrote in an email that in the first two months of this year, the company conducted more than 2,000 inspections on homes in Suffolk County and more than 1,300 in Nassau County. “Our property preservation inspectors provide detailed reports of maintenance activities, including photos, every 25-35 days,” he wrote.

Bank of America spokesman Rick Simon wrote in an email that he could not provide “specific proprietary detail” about the company’s preservation measures, other than to say that they order regular inspections to determine if a property is vacant. He also stated that Bank of America takes “routine maintenance and preservation measures to protect the collateral value of the loan and mitigate neighborhood impact.”

Officials with Ohio-based Safeguard Properties, one of the largest property preservation companies in the United States, declined to answer questions about their practices, including how often they inspect properties. They noted in a statement that there are “industry standards for property maintenance, however banks, as well as cities and counties, can impose additional and varied guidelines, which we work within when inspecting, securing and maintaining properties.”

Ronnie Ory, president of Florida-based preservation company Cyprexx Services LLC, said he has 500 employees in a call center who hire local contractors. Nationally, the company has about 20,000 contractors and uses 4,000 to 5,000 of them each week, he said. On Long Island, Cyprexx uses about 40 to 50 companies for property cleanups.

Banks give Cyprexx a list of work needed on their properties, Ory said. Debris removal “is usually on top of the list” he said, followed by cutting grass, trimming bushes and making the house exterior “look very presentable.”

Lenders are “trying to do the right thing,” Jafri said. “Nobody wants to have an asset or a property that’s in disarray, but the question becomes at what cost? How much can a lender do and in what capacity can they get in there?”

Several lawsuits have been filed in recent years against property preservation companies for overstepping their boundaries. They include a 2013 case by the Illinois state attorney general against Safeguard for incorrectly declaring homes vacant, going inside, shutting off utilities and changing the locks.

Nationstar spokesman John Hoffmann wrote in an email that it can be difficult to determine when a home becomes vacant, a process made more problematic by varying county and city definitions of “abandonment.” Even if a property appears abandoned, he wrote, “the servicer may be subject to claims of trespassing if it attempts to initiate any repairs or maintenance.”

As a result, he wrote, it is difficult for servicers “to maintain a perfect balance between maintaining a property and honoring a homeowner’s rights to possession of the property prior to foreclosure.”

Wells Fargo won’t send people inside homes for maintenance because it could be construed as trespassing, Smith said, and their ability to do repairs is limited. “We can do some of the exterior maintenance but we can’t repair the foundation on a home we don’t own,” he said.

Wells Fargo works with municipalities on maintenance issues and places stickers on houses with contact information for complaints about maintenance or other issues, Smith said. “We want to know if there’s something wrong with one of our properties. If there’s a lawn that isn’t mowed, we want to know about it,” he said.

Other financial companies appeared to know little about the condition of their properties on Long Island.

Dico Akseraylian, a spokesman for PHH Mortgage in Mount Laurel, New Jersey, was given more than five months by a Newsday reporter to research three properties that had been boarded-up by Babylon Town after numerous calls and certified letters from town officials went unanswered.

Akseraylian indicated he was unaware the town had boarded up the homes. He said he did not have an answer when asked why PHH had let the properties deteriorate to the point that they had graffiti, raccoon infestations and squatters. He denied the company had been contacted by the town for two of the homes. After being given copies of the certified letters sent by the town, Akseraylian did not respond to additional requests for comment.

Shanna Smith of the National Fair Housing Alliance said the lack of awareness by servicers is a big part of the reason so many homes continue to fall into disrepair.

“Everyone seems to have good policies for taking care of the properties but they’re all really lousy about making sure the work gets done,” she said.

Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae representatives declined to discuss specifics about their methods but insisted that they monitor property maintenance by their servicers.

“We routinely audit servicers for compliance with our guidelines as well as insuring that they have in place good controls, policies and procedures for implementing our requirements,” said Freddie Mac spokesman Brad German, adding that servicers must have photos of properties to show the work has been done. “If something wasn’t done that should have been done,” he said, the company would seek compensation upon foreclosure.

Cyprexx ensures compliance by its contractors by using its own inspectors to conduct random checks to make sure work is being done, Ory said. The company also requires contractors to submit before and after photos for houses they have worked on in order to receive payment.

But those methods can be flawed.

In 2012, the Office of Inspector General for the Federal Housing Finance Agency investigated Florida-based American Mortgage Field Services, a property preservation company that was hired by Bank of America for mortgages owned by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

According to the inspector general’s report, the company’s owners sent fraudulent reports, including using photographs from previous inspections that had the dates changed to make it appear as if new inspections had taken place. As a result, the report states, the company fraudulently received $12.7 million over three years for property inspections that they never conducted.

The report found a “problem which may be systemic throughout the industry.” Two owners of the company pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit wire fraud and served time in federal prison.

Financial institutions have paid the U.S. Department of Justice nearly $37 billion to settle charges of wrongdoing related to the housing crisis, including Bank of America’s nearly $17 billion accord in August, the largest civil settlement with a single entity in the nation’s history.

Banks have paid for making those bad loans and “now they’ve got to pay for the results and the harms to the communities of the foreclosures that are left from those bad loans,” Smith of the National Fair Housing Alliance said.

“The rest of us who still live in the neighborhood, we’re the collateral damage,” she said. “And the banks can’t get away with that.”

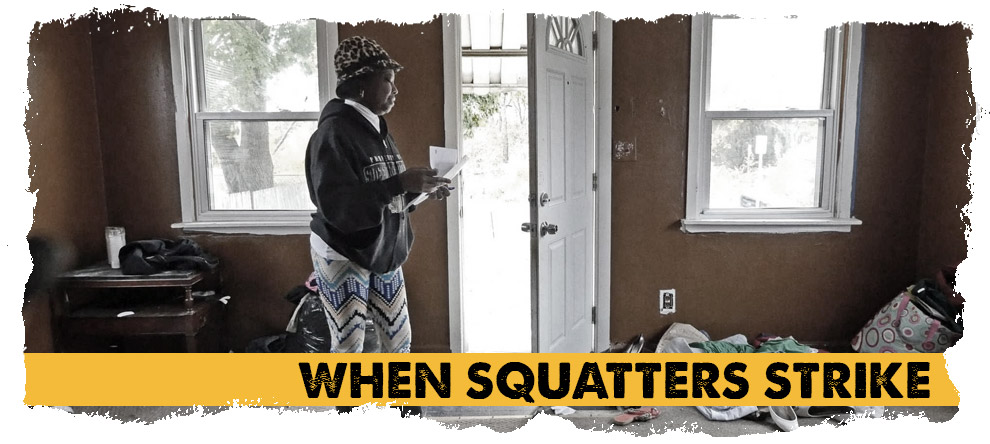

Amencia Larose looks through the Wyandanch home on Friday, Nov. 7, 2014, that she says squatters took over. (Photo credit: Newsday / Chuck Fadely)

Amencia Larose bought a house in Wyandanch in 2005 for $140,000 with plans to expand, improve and sell it.

But when she couldn’t find a buyer and renters stopped paying, the home sat vacant until last year when Larose, 52, found herself facing the most frightening consequence of Long Island’s abandoned house crisis: squatters.

People who illegally occupy a home create problems for neighborhood residents ranging from the aggravation of noise to the danger of gang activity. Squatters often damage the homes, remove anything of value and make the house unsafe for first responders or neighborhood children who venture inside.

Under New York’s real property law, anyone living in a residence for 30 days or more is considered a tenant and can only be removed through a court eviction proceeding, which can take six months or longer, according to local officials and real estate agents.

Police and local officials put squatters in several categories: people who are homeless and looking for a place to live; those looking to set up drug dealing or o#tther illegal activity; people duped into renting by someone posing as the homeowner; and those for whom squatting is a full-time endeavor.

Larose, who works for the state’s Long Island Developmental Disabilities Service Office, said she believes it was the last type of squatter who put her “through hell” by moving into her house, tearing off doors, pulling up flooring, breaking fixtures and flooding the house.

In 2013 she started working with her mortgage servicer, Bank of America, to sell the house for less than the amount she owed — what’s known as a short sale. A bank appraiser said the property was worth $63,000, according to Larose’s real estate agent, Elma Phifer of Blackstone Property Inc. in Greenlawn.

But the bank wouldn’t accept offers at that price. Bank of America spokesman Rick Simon said Freddie Mac, a federally chartered corporation that buys mortgages, had a set minimum for the house “considerably higher” than $63,000.

As a result, the house sat empty for six months. Larose checked on it weekly and said in April she noticed curtains in the front window and a new front door.

A woman came to the door and said she was renting the house. She’d had the water and electricity turned on in her name, Larose said.

Larose called the police who said they could only investigate the squatter’s claims. One officer told Larose he recognized the woman and that she had similarly moved into other houses.

Larose gave police copies of her deed, home insurance and property tax bills. She was told to start eviction proceedings.

As she waited for a court date, she continued to check on the house. Each time more people were there and a late model Mercedes-Benz was in the driveway, Larose said. The squatters yelled and threatened to beat her up, telling her she was trespassing, she said.

“The whole thing was just so unreal,” she said. “It’s like a nightmare and every day you hope you wake up from it.”

Before she could get an eviction order, the squatter who had met Larose at the front door signed a court agreement to leave the house on Oct. 15. But when Larose showed up at the house that day, she said, the woman told her she wasn’t leaving.

Larose said she paid more than $400 to have the Suffolk County Sheriff’s Office remove the woman, a process that can take one to two months. The department charges fees based on the number of occupants, travel distance and amount of possessions that have to be removed.

The squatters left on their own two weeks later, before being evicted.

When Larose went to the house with police, the door was locked. Officers refused to let her in, saying that without the key, the home was still in the squatters’ possession, she said. Larose looked in the window and saw the kitchen faucet running into a plugged sink and flooding the home.

Larose got the Suffolk County Water Authority to shut off the water. Days later, a mattress that had been outside was now inside the house, Larose said. The squatters were back.

A week after that, Larose noticed the front door wide open. She called the police and was finally able to get inside.

What she saw horrified her: missing bedroom and closet doors, cracked window panes, torn flooring and carpet. There was a hole in a bedroom ceiling, a chunk of the bathroom sink had broken off and scribble marks covered the walls. The toilet was full of waste and the bathtub crusted in varying shades of brown. The oven and refrigerator Larose had purchased were gone. Even the smoke detectors were missing.

Left behind were beer cans, takeout food containers, diapers and clothing strewn across the floors, ashtrays full of cigarette butts, and a broken baby carrier.

“You put so much energy, so much of your finances, into everything and somebody just ruins it,” Larose said. “It’s just sickening.”

Bank of America’s Simon said squatters are one of the biggest challenges in the preservation of homes going through the foreclosure process. “Even when properties are reasonably secured and under routine inspection, complete security cannot be guaranteed,” he wrote in an email.

Without the bank having title to the property, the squatters “have to be treated as if they are bona fide occupants,” Simon said. “The current owner, not the mortgage servicer, has the legal authority to request eviction.”

Police said their role is limited in most squatter cases. “They say ‘I’ve been living here for six months and I’ve been paying rent’ — well how are we going to disprove that?” said Insp. Gerard Gigante, commanding officer of Suffolk County Police First District. “We’re generally not going to throw anyone out on their feet based on the opinion of what that patrol officer thinks. It’s going to get a follow up investigation.”

Unless there’s obvious illegal activity taking place such as selling drugs, squatter cases are rarely resolved as quickly as neighbors would like, he said.

“Chances are it’s been going on for a while so another day, week, or two weeks or a month isn’t going to make a difference,” Gigante said. “The process can slow down a little bit because it’s not an emergency.”

Police said banks often decline to file charges against those who break in and steal copper and other materials from a house in the foreclosure process. Suffolk First Precinct Officer Jeff Blaskiewicz, who serves as a community liaison, said police try to get banks to sign trespassing affidavits so they can keep them on file and pursue criminal charges on any future incidents. But those are “few and far between” he said.

“It’s frustrating for everybody,” Blaskiewicz said. “They don’t really want to make arrests, they just want people out of the buildings.”

Wells Fargo spokesman James Hines said in an email that the bank considers affidavits on a case-by-case basis.

Without a complainant, police cannot pursue charges.

“We can’t go to a house and lock someone up for trespassing” without the owner filing a complaint, Gigante said. “The neighbor’s word isn’t good enough.”

Police said the easiest solution — boarding up the house — often is not one that neighbors welcome.

“People don’t want the squatters in there but they don’t want the house boarded-up either,” said Insp. Robert Brown, commanding officer of Suffolk County Police Third Precinct.

Gigante said his officers conduct patrol checks on abandoned houses that are known to have problems. The checks are reviewed monthly and if Gigante feels some homes are still vulnerable to illegal activity, he will increase the effort.

Police said they advise homeowners and banks to pursue eviction of squatters. But the process can be prolonged by savvy squatters who “use every legal obstacle they possibly can,” said Valley Stream Village Clerk Robert Barra.

As a result, some banks have long had a “cash for keys” policy, real estate agents said, offering money to squatters who refuse to move out. The pay can be several thousand dollars and accomplished squatters know which banks pay the most, targeting those properties, officials said.

Wells Fargo’s Hines said the bank offers “financial relocation assistance to non-owner occupants.”

A state judge recently recommended cash for keys, said Allison Schoenthal, an attorney who represents lenders for Hogan Lovells in Manhattan. The judge acknowledged that a squatter was breaking the law by occupying a bank-owned house in Queens, but suggested the lender pay the squatter the equivalent of moving expenses or one to two months rent, she said.

Squatters’ ability to get utility service in homes they occupy is another frustration to municipal officials. The squatters often show phony leases or aren’t required to provide more than an ID to get water or power turned on.

Mastic Beach code enforcement officers last year responded to reports from residents about an electrical wire running across one of the busiest roads in the village. They found 17 people living in a house and stealing the electricity from another abandoned home across the street, Mayor Bill Biondi said.

Utilities often do not require proof of a lease or deed unless there is an outstanding balance for a home or a person requesting service.

When water service is requested, the Suffolk County Water Authority requires a driver’s license number, social security number or other form of valid identification for service to start, spokesman Tim Motz said in an email.

PSEG Long Island has a similar policy, spokesman Jeff Weir said, pointing to the Tariff for Electric Service and the state Home Energy Fair Practices Act that dictate many of their policies. Both laws were enacted to protect consumers and ensure they continue to receive gas and electric service during disputes.

If a homeowner reports someone squatting in their house, PSEG cannot turn the power off, Weir said. Electricity would only be turned off if a home is unoccupied. The water authority has a similar policy.

“We can’t simply turn the water off due to the complexity and legality of landlord/tenant relations,” Motz said. Courts, not utilities, have the authority to decide who is entitled to occupy a property, Motz said.

“The bottom line is we do what we can to assist the proper authorities,” he said. “When a town provides us a list of premises that are abandoned or at which they suspect illegal occupancy, we’ll make every effort to prevent new accounts from being started at those premises.”

Squatters often just move to another vacant home, sometimes in the same neighborhood.

In the past two years, about a third of the abandoned houses in Babylon Town have had squatters in them, said Edward Buturla, lead inspector with the town’s environmental control department. Sometimes they use a phony lease and rent the house to someone else, he said. One squatter moved among five different houses in the town.

The problem has been acute in the Parkdale neighborhood of North Babylon. In late 2013, neighbors mobilized after finding squatters had moved into several vacant homes, with one family, including young children, moving back and forth between houses. When neighbors started documenting the situation, the squatters called police, alleging harassment, officials said.

“It’s a magnified example of what can happen in a very small neighborhood if you have a number of these homes that are abandoned where squatters take up residence,” said Babylon Supervisor Rich Schaffer. “It not only affects the property values of the neighborhood but the public safety of the neighborhood.”

As a result of the town working with the community, many of the homes were boarded-up. The Parkdale Civic Association became more vigilant and a Neighborhood Watch was formed, association president Terry McSweeney said.

But staying vigilant comes with a cost, Schaffer said. “It takes time away from a lot of things that people should be doing,” he said. “They’ve got kids, they’ve got jobs, after school activities — why should they have to deal with this?”

Larose said until she is able to sell her Wyandanch house, she worries about other squatters moving in and causing even more damage.

“This is what happens when the system fails you,” she said. “These people have all the rights. Once they go inside, they have all the rights.”

With Maura McDermott and Deon J. Hampton

Under the state’s real property laws, individuals living in a residence for 30 days are considered tenants and can only be removed through a court eviction proceedings.

Squatters must be first given a 10-day notice to “quit” the property.

If the squatter doesn’t leave, the matter moves into the local district court.

The case usually begins within weeks, but there can be delays and that take months.

When a judgment is made for the squatters to leave, the order is sent to the sheriff’s office.

The sheriff’s office serves notice and the squatters have 72 hours to voluntarily vacate the property.

If the squatters fail to leave, the sheriff’s office — which may take weeks or months to act — can remove the squatters and their possessions from the property.

Source: Warren Berger, Central Islip attorney who handles eviction cases; New York state real property laws

A house in Selden is demolished on Feb. 23, 2015. (Photo credit: Ed Betz)

Local and state governments are developing new ways to fight Long Island’s abandoned home crisis. Municipalities are creating registries of vacant homes and new laws to tackle blight while the state is attempting to hold financial institutions more accountable for homes in foreclosure that become eyesores or hazards.

Newsday’s yearlong analysis of the problem found that towns and villages across the Island last year spent at least $3.2 million to clean, board up and demolish abandoned homes. Most of the properties are what have become known as zombie houses — those being foreclosed on by financial institutions and the owner has walked away.

Four Suffolk towns and three Nassau villages have established vacant-home registries. Depending on the location, banks have between 15 and 120 days to register empty houses with the municipality or face fines between $100 to $2,500.

Some towns have focused on trying to control blight before a house deteriorates to the point the town has to maintain the property.

Huntington, which in 2014 spent nearly $31,000 on cleanups and board-ups, last year assessed 61 properties more than $182,000 for violating its 2012 blight law.

The town assigns points based on the severity of the problem. For example, a house would receive five points for broken shutters and 50 points for having a fire hazard. When the house reaches 100 points, the owner has to agree to fix the problems. If the owner does not enter into an agreement with the town within 30 days, the town adds a $2,500 fee to the property’s tax bill.

Brookhaven officials in December approved a point system to determine whether a house should be repaired, boarded-up or demolished. A municipal court hearing is scheduled if the house isn’t brought into compliance. If the owner fails to appear, Brookhaven could repair or demolish the property.

“That is a desperate measure from a town that is overwhelmed by these problems,” Brookhaven Town Supervisor Edward P. Romaine said. Over the past year, the town has torn down eight houses from among 12 “Dirty Dozen” homes scheduled to be demolished because they are structurally unsound.

Babylon Town departments are working together to create a digital mapping system for abandoned homes and streamline the process of monitoring and maintaining blight. The work now involves five or six departments and is their most complicated task, said John Cifelli, Babylon’s director of operations.

Deputy Supervisor Tony Martinez said the proliferation of abandoned homes in the town — the number has reached nearly 200 — led officials to find new ways to address the problem. By mapping the homes and building a database that includes the property history, Babylon officials hope to identify blight at the neighborhood level while looking for patterns to prevent more abandoned homes.

“This came out of the frustration with all the clean-ups we do, all the calls that we get,” Martinez said.

Towns and villages also have been working to improve the aesthetics of boarded-up houses. Islip crews paint the plywood a neutral gray and Babylon Town workers match boards to the home’s exterior color. Islip workers also have started boarding up dilapidated homes from the inside and outside to try to prevent boards from being easily removed.

This week Nassau County Executive Edward Mangano and state Assemb. Todd Kaminsky (D-Long Beach) announced the launch of a new online database where residents in the county can submit information and photos of abandoned homes in their neighborhoods. The county assessor’s office will research the ownership of the homes and relay that information to towns and villages, who can then contact the owner or bank to bring the property up to code. The City of Long Beach is currently the only municipality that will be entering its log of abandoned homes into the database but Mangano said he is reaching out to other municipalities to take part.

In Suffolk County, the state Supreme Court last year created a fast-track procedure for abandoned homes in foreclosure. If a municipality identifies a home as abandoned, and the homeowner has not filed any legal papers or appeared in court, the court skips the usual process of appointing a referee to calculate the amount owed. Instead, if Suffolk County District Administrative Judge C. Randall Hinrichs determines that a foreclosure sale is warranted, the judge calculates the total debt.

That can save nine months or more, a court spokesman said.

In the year since the program began, the court has identified about 400 abandoned homes in foreclosure, the spokesman said. That’s 2.7 percent of Suffolk’s roughly 15,000 pending foreclosures.

Nassau County’s state court created a fast-track foreclosure process in mid-2013 for cases where homeowners have never shown up in court or filed any legal papers, a court spokesman said. Nassau has seen about 2,000 fast-tracked cases, out of a total of 9,700 pending foreclosures.

At the state level, attempts are being made to speed up the state’s foreclosure process, which averages 934 days, and hold banks responsible for maintenance on vacant homes.

State Assemb. John T. McDonald III (D-Cohoes) is drafting legislation that would create a fast-track foreclosure process for abandoned homes with delinquent tax bills.

New York Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman last month proposed legislation to force banks and mortgage companies to start maintaining homes as soon as they become vacant and not wait until there is a foreclosure judgment. The proposed bill also establishes an inspection schedule for banks to determine if a property is being occupied by squatters.

The legislation has not been introduced. It is an expansion of a bill Schneiderman proposed last year that died in both the Assembly and Senate.

Schneiderman told Newsday the legislation “is very much targeted at helping the local governments on Long Island deal with this really, really damaging issue for many communities.”

As part of the proposed Abandoned Property Neighborhood Relief Act, banks would have to electronically register vacant homes in the foreclosure process with the state.

“Until we have a statewide registry we’re never going to have accurate numbers,” Schneiderman said.

Data from California-based RealtyTrac, which compiles real estate statistics, show 4,044 zombie houses on Long Island, a number Schneiderman said is “low.”

The Vacant and Abandoned Property Registry would be supplemented by a toll-free hotline that residents could use to report suspected abandoned homes. The hotline also could be used to gather information on registered properties, including their status and who is responsible for maintaining them.

“The problem with zombie properties right now is that the neighbors can’t figure out who’s in charge, most times local government can’t figure out who actually holds the mortgage,” Schneiderman said. “So this is going to force, in one bill, transparency about who owns what properties in the state of New York.”

If the bill is enacted, failure by banks to comply would result in fines of $1,000 per day for each violation of failing to register a property or failing to maintain it. The money would be directed to a fund for local governments to hire additional code enforcement officers.

It is unclear how much support Schneiderman’s bill will get. Senate majority leader Dean Skelos (R-Rockville Centre) did not return repeated calls seeking comment.

Garden City-based attorney Bruce Bergman, who represents banks, said the attorney general’s proposal would impose potentially enormous financial burdens on lenders — not just the cost of maintenance, but liability for hazardous conditions and fires. Bergman said it’s not always clear whether a house has been abandoned, nor is it clear how often lenders would need to inspect homes to make sure they are in good condition.

Schneiderman’s proposal would force lenders to maintain properties for years even though they do not own the homes and it would expose lenders to charges of trespassing, said Marianne Collins, executive director of the New York Mortgage Bankers Association.

“How much do we want to drain the assets of the lender?” Collins said. “Rates will be higher, closing costs will be higher, because lenders have to stay in business.”

If New York fast-tracked foreclosures of abandoned homes, “the process would be over in 60 days instead of three years,” she said.

State Sen. Tom Croci (R-Sayville), the former Islip Town supervisor, said he is not sure if he will support Schneiderman’s legislation, but added he will take “a really hard look at it.”

Croci said he plans to find other ways the state can help combat problems associated with vacant dilapidated homes.

“I’ve seen the complexity, I’ve seen the difficulties that towns have,” he said. “If there’s a way from the state government perspective … that we can give the towns the tools to more effectively deal with this situation, I’d love to be in a position to investigate how to do that.”

Officials in Nassau and Suffolk counties have expressed support for Schneiderman’s bill.

“Anything to make these banks not hide behind the excuse that they’re not the legal owner of the property,” Martinez said.

“We need as many tools in the arsenal as we possibly can get,” Hempstead Town Supervisor Kate Murray said. “I think it [Schneiderman’s proposal] could go a long way in at least keeping the facade of these foreclosed homes in decent shape.”

The legislation would bring much needed help to smaller municipalities, said Valley Stream Justice Robert Bogle, who handles village summonses that are given to banks and homeowners and also reviews foreclosure cases as a supervising court attorney in Nassau County Court.

A state registry would “be really helpful to the little villages and towns throughout New York State that don’t have the manpower to do research on these matters,” Bogle said.

But the number of abandoned homes across Long Island and their associated maintenance costs steadily climb each year, and municipal workers often have to make repeat visits to properties.

Douglas Bunge, 66, lives near an abandoned home in Bay Shore that was boarded-up by Islip Town last month. The house — across the street from an elementary school — had become a hangout for trespassers, he said, and the town oarded it up inside and out. But within weeks, someone ripped out the window frames and removed the boards, Bunge said.

“It’s a continuing problem,” Bogle said. “And it could very well be a problem that will be with us for many, many years ahead.”

Examples provided by the Town of Babylon. Click the points on the photo for more information.

Structural damageStructural damage at abandoned homes can lead municipalities to board them up. The average cost of a board-up is about $3,700.

Tree trimmingOvergrown vegetation often leads to complaints that municipal crews have to address. The costs average between $500 and $1,000.

Grass overgrownComplaints about overgrown grass can result in municipal work crews mowing lawns at abandoned houses. These costs average between $500 and $800.

Debris removalPiles of trash and debris are removed by work crews. These costs average between $500 and $2,000.

Accessible entranceOpen doors are boarded up to prevent entry. The average cost of a board-up is about $3,700.

BOARD-UPSBroken windows and open doorways lead to properties being boarded up. The average cost of a board-up is $3,700.

DEMOLITIONIf the property is deemed unsafe, municipalities will seek to tear it down. The average cost of a demolition is $25,000.