Jo’Anna Bird’s murderInside her final months: ‘She really felt like she was going to die’

Jo’Anna Bird was sure that her violent ex-boyfriend would murder her. She sought help from the police – but with information from a long-secret file, Newsday reconstructs how officials mishandled her case.

Content warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of domestic violence.

Jo’Anna Bird knew there was no escape.

She could only dream that she might ever live free from fear and brutality. No more torture. No more kidnapping. No more threats to kill her, her sisters, her mother.

It hadn’t always been that way. While still in high school, Bird had gotten pregnant, and things didn’t go as she had hoped. Her boyfriend dumped her. Feeling vulnerable and alone, she agreed to let another man into her life, a suitor who brought her gifts like candy, teddy bears and flowers.

But that suitor, Leonardo Valdez Cruz, who promised to always love and support her, turned into something else.

Over time, she came to realize that no matter how hard she tried to break with him, Valdez Cruz would refuse to release his grip.

That no matter how often and desperately she pleaded for help, the police would fail to protect her.

Watch the Newsday documentary

In the last months of her life, Jo’Anna Bird was sure that Valdez Cruz would murder her.

“Please tell Mommy to dress me like myself,” she told her sister Melissa, envisioning her funeral. “Like I don’t want to be in a suit or dressed like an old person. Dress me young, how I look now.”

Valdez Cruz had spelled out exactly what he intended to do to Bird in letters and recorded phone calls from the Nassau County jail.

He said that he would “make her f—in’ eyes pop out (of her) f—in’ head” were she to leave him.

In one letter, he threatened, “if I had the chance I would cut you in your f—ing face.”

In another, he warned: “It’s not gonna KILL you to give me one last chance. It might KILL you if you don’t.”

Jo’Anna Bird was as trapped as any character in a horror movie could be.

Except the monster that had emerged in once-charming Leonardo Valdez Cruz was relentlessly real in monitoring who she was talking to, in tracking her to her job as a school bus matron, in subduing her with a Taser, in kidnapping her, in promising her that he would kill the people she loved most if she reported his violence to police.

Bird did what she could to escape. She did what she was supposed to do.

She went to court and secured orders of protection, directing Valdez Cruz to stay away under penalty of arrest.

Valdez Cruz, a member of the violent Bloods street gang, shrugged off the orders.

Bird called the police. They shrugged off the need for action.

Again, again, again and again.

Until, just as he had vowed, Valdez Cruz fatally stabbed and slashed Bird in her Westbury home, propped her body on a staircase and fled.

The date was March 19, 2009, but only now has a long-secret Nassau County Police Department internal affairs file enabled Newsday to reconstruct the official indifference that proved fatal for Bird.

In 2010 and 2013, Newsday waged court actions seeking access to the information. Judges rejected the requests, citing a New York State law that barred public disclosure of police disciplinary records.

That law was repealed in 2020. Even so, the police department denied Newsday’s renewed application for the documents in a Freedom of Information Law petition that also sought numerous unrelated internal affairs records. Newsday sued. A Nassau Supreme Court justice upheld the department’s argument that releasing the disciplinary documents sought by Newsday would represent an unwarranted invasion of officers’ privacy. Newsday is appealing.

Independently, in a nationwide look at policing, a consortium of New York news organizations working with USA Today asked the Nassau County District Attorney’s Office for copies of records that prosecutors are required to turn over to criminal defense attorneys. Such records contain information defense attorneys may use to impeach prosecution witnesses. Upon request, the Nassau DA routinely releases such records.

The DA’s office emailed the long-sought file to USA Today because a police officer scheduled to testify in a case was named in the records. USA Today’s editors then proposed a partnership that would rely on Newsday’s deep Nassau contacts and knowledge about criminal justice on Long Island.

While Police Commissioner Patrick Ryder has maintained that the police department has the power to seal the file from public view, the district attorney’s office determined that the repeal of the secrecy law mandated releasing the document.

“This agency disclosed records responsive to a 2020 request based upon our interpretation of our obligations under the FOIL statute following the legislature’s repeal of § 50(a) of the New York State Civil Rights law,” the district attorney’s office explained in a written statement.

Comprising 781 pages, the file provides the chronology that the department used in charging 11 police officers, one detective and two sergeants.

It does not, however, reveal why the Nassau Police Department Internal Affairs Unit focused only on the last four months of Bird’s life; shows no evidence that the unit held superior officers accountable; and does not disclose the penalties meted out to officers.

Ryder refused to release the punishments, as well.

After the politically powerful Nassau Police Benevolent Association intervened with then-County Executive Edward Mangano, the penalties were limited to as little as the loss of four hours of sick or vacation time to a maximum deduction of 24 days of sick or vacation time, according to well-placed sources and records. The department ordered retraining for one officer.

The department imposed the lowest financial penalty on Det. Jeffrey Raymond, who now heads Ryder’s Burglary Pattern Squad. Policing experts who reviewed the file for Newsday singled out Raymond as the officer most culpable for failing to protect Bird.

The file’s chronology offered a framework for telling the intertwined stories of the terror under which Bird lived and the Nassau County Police Department’s failures to safeguard her life. Newsday supplemented that account with interviews with Bird’s family and friends, a prison interview with her killer and the judgments of the policing experts.

The 14 officers declined to be interviewed.

JO’ANNA

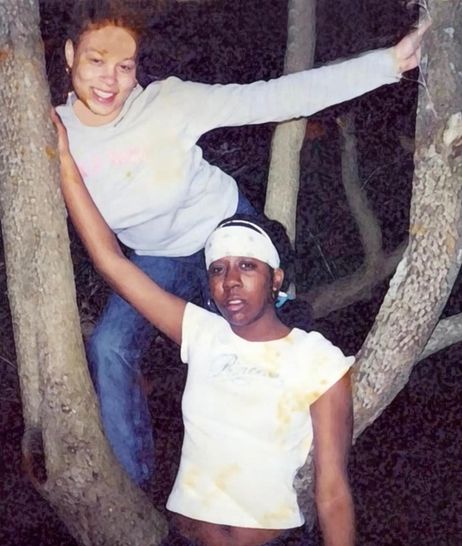

Growing up, Jo’Anna Bird was a girl who knew her own mind.

She was a tomboy. She liked to hang out with the boys, climb trees and play touch football. She usually dressed in pants and a T-shirt, and sometimes a baseball cap. Her mother fought to get her to wear a dress for middle school graduation.

People wanted to be around young Jo’Anna because she was fun. Her siblings squabbled over sitting next to her on car rides.

“Everyone loved being around her,” her sister Melissa said.

Bird did well in school. She talked about growing up to become a pediatrician, said her best friend, Latina MacFadden.

“She wasn’t the one to go to parties,” her mother said. “She’d stay home and let her best friend go to the parties, and then her best friend would come and tell her everything that happened at the party.”

The third of nine children, Bird was a senior at Westbury High School when she got pregnant. She graduated and was excited about becoming a mother and continuing her education, her friend Sheena Rudder said.

“I would call her like a divine spirit,” said Rudder, who also was a young mother. “She was the truth of anything, you know. I could share anything that I was going through with her, and it would be a no-judgment zone. And she would give me her opinion – right, wrong or indifferent. And I would accept it because I knew it was sincere.”

When the father found out that Bird was pregnant, he made it clear that he didn’t want a child. He joined the military and shipped off to the Iraq war, family members said.

Though hurt and upset, Bird persevered. She worked at BJ’s Wholesale Club and made plans to go to vocational school to get a better job.

In this unsettled time, Bird met Valdez Cruz.

It was the summer of 2002. Bird’s family had just moved to Westbury, where Valdez Cruz, nicknamed “Pito,” hung out. Her large family – three boys and six girls – had moved around a lot. Her brothers knew the streets well. That’s where they met Valdez Cruz.

Like neighboring New Cassel, where Bird’s family had previously lived, Westbury is one of Long Island’s more diverse communities. Nearly 22% of the population is African American, and about 27% is Hispanic, according to the latest Census.

Valdez Cruz spent much of his time on Prospect Avenue, a busy Westbury thoroughfare. One day, Bird met her brothers at a corner store. Valdez Cruz saw her and was smitten.

“The minute that I seen Jo’Anna, I was caught off track,” he said in a prison interview. “I was, ‘This woman is beautiful. I gotta, I gotta, I gotta talk to her.’ You know um, she was just, she was just glowing. You know, she had beautiful eyes, nice skin, nice hair.”

He followed Bird’s brothers home to find out where she lived. Then he started showing up at her family’s house on the pretense that he had come to see her brothers, but he brought her those gifts, the candy, teddy bears, flowers.

Bird’s mother took an immediate dislike to Valdez Cruz.

“There’s something about him,” she would say.

Bird told her mother to give Valdez Cruz a chance. She appreciated his attention, gestures like walking her home from the bus stop after a night shift at BJ’s.

He kept coming around “like a tick on a dog,” Bird’s friend, Latina MacFadden, said.

Valdez Cruz agreed that he was “very persistent.”

“It took me six months to really get her attention,” he said. “She was hard. She was a good girl.”

When he discovered that she was pregnant and that the father wouldn’t be around, Valdez Cruz offered to step in. Faced with being a single mother, Bird finally agreed to accept his help.

“All Jo’Anna wanted was somebody to love her and respect her and stand by her just as much as she did for them,” said her sister Sharon. “And that’s all anybody ever wants.”

Valdez Cruz was at the hospital for the birth of her daughter, Joanna, in March 2003.

‘Men — not men, cowards — prey on vulnerable women … They can know exactly where to work them.’

Sheena Rudder, Bird’s childhood friend

“Everything was so, so good at this point,” Valdez Cruz said.

But Bird’s family and friends saw danger that she failed to see.

“Men – not men, cowards – prey on vulnerable women,” Rudder said. “I feel like they can smell their weakness. They can smell their fears. They can smell their vulnerabilities. They can know exactly where to work them.”

VALDEZ CRUZ

Valdez Cruz was all of 12 years old in 1997, the year he was arrested for the first time.

He had pointed a BB gun at the heads of two elementary school children and threatened to kill them. The BB gun wasn’t loaded; the case was dismissed.

Nearly every year after that, he was arrested again, according to the internal affairs file and court records. In the prison interview, Valdez Cruz confirmed his past.

In December 1998, it was for robbery. The following August, he was charged with second-degree assault after an argument with his mother’s boyfriend. In a separate incident, he was arrested at Westbury Middle School in November 1999.

Valdez Cruz spent roughly the next two and a half years in a state residential facility for juveniles, an experience “that made me a little hardened on the outside,” he said.

Released, he enrolled in Hicksville High School but cut class more often than he attended school. He focused on selling drugs to fellow students and evading security guards, he said.

“I was already tearing up the streets,” he remembered.

When he was in 11th grade, school officials called in the police after he was selling drugs there, Valdez Cruz said. He never returned to school.

In June 2002, police charged him with criminal mischief for damaging a car. By then, police records show that Valdez Cruz was a member of the Bloods, a violent street gang.

Around this time, he met Bird.

He wasn’t working. In fact, he never held a job for more than a couple of days – but he was flush with cash. He was peddling angel dust, also known as PCP, an illegal psychedelic drug commonly sold in powder or liquid form. Valdez Cruz opted to sell the more popular and expensive liquid form.

A wholesale source in Harlem charged $500 for an ounce. He made the investment, then pulled down $3,500 to $4,000 cutting the drug for sale on the street in Westbury, he said.

Bird disapproved of his drug dealing, he said, but she was coping with working a couple of jobs and going to vocational school. She would take courses to learn office skills and to pass the civil service exam for becoming a correction officer. She was also caring for the baby.

In April 2003, when infant Joanna was a month old, police charged Valdez Cruz with robbing $20 from a man and slashing him in the face. The victim, a stranger, needed 30 stitches to close the wound.

Over the next two years, Valdez Cruz cycled in and out of jail.

In March 2005, Bird gave birth to a son, named Leonardo after his father.

The last, horror-filled phase of her life had begun.

BIRD TRIES TO BREAK AWAY

Bird called police a month after Leonardo was born. She wanted Valdez Cruz to leave her apartment, but he refused to go. The police took no action. The internal affairs file reveals nothing more about what happened.

Bird called police again in August that year after she and Valdez Cruz argued over his visiting 4-month-old Leo. The police took no action. Bird agreed to clarify in court his ability to see the infant. Again, the file provides no details.

Increasingly obsessed with Bird, Valdez Cruz grew volatile. In the prison interview, he blamed his violence on a budding angel dust habit.

“Once I started doing that stuff, everything just went downhill,” he said.

But he was overbearing and violent even when sober, her sisters said. He followed her to work, demanding to know who she was talking to. He took her phone apart to stop her from calling for help. More than once, he tied her to an apartment radiator. He choked her until she passed out.

In the fall of 2005, Bird got some relief. Valdez Cruz started almost eight months in jail after an arrest for driving while high and trying to pass two counterfeit $100 bills. Within a few months of his release, police arrested Valdez Cruz twice more, first for driving with a suspended license and then for selling cocaine. He was sentenced to one year in jail.

Bird told Valdez Cruz their relationship was over. He cursed her in a letter for not visiting him behind bars, writing, “You have been a f—ing lost soul to me this bid and I will never forget this bid.”

Valdez Cruz was freed in 2007, shortly before Bird applied to become a correction officer. He resumed his single-minded, violent pursuit. But the internal affairs investigation did not focus on the police response to how he tormented Bird until the end of the next year.

In June 2007, she reported that Valdez Cruz had punched her over the right eye – and the police department started its record of inaction.

The police file states that Bird declined to press charges.

“For some reason, she never wanted to see him hurt or in jail,” her brother Joseph said.

The file does not explain why officers did not use the state’s mandatory arrest law to take Valdez Cruz into custody.

The statute requires police to make an arrest, regardless of a victim’s wishes, when there is probable cause to believe that a crime has been committed or that an order of protection has been violated.

Three weeks later, Valdez Cruz, by now 22 years old, yanked an 11-year-old boy off his bicycle in an unprovoked attack. He slammed the boy to the ground, dragged and punched him. Two witnesses pulled Valdez Cruz off the child.

As was his pattern, he blamed forces beyond his control.

“Somebody laced my smoke with PCP,” Valdez Cruz told police, whose records identified him as a member of the Bloods.

Returned to jail, Valdez Cruz stewed about the possibility of another man around Bird and the children.

“I wanna let them know that they only have 1 father and daddy and that’s me and only me and NO ONE ELSE,” he wrote her.

With Valdez Cruz sentenced to eight months, Bird saw a chance to get away, Melissa said. She found an apartment in Westbury and planned to keep its address secret from him.

Then Valdez Cruz’s sister, Aurea, insinuated herself into the situation. A protector and helpmate to her brother, she by then had compiled her own rap sheet, with three arrests, one for driving without a license and two for the possession and sale of a controlled substance. Aurea told Bird that she had no place to live. Bird agreed to let Aurea move in – on the condition that she didn’t share her address with her brother.

“My sister had a big heart,” Melissa said.

The generosity proved disastrous. Before long, Valdez Cruz started calling Bird’s new phone number from jail.

Released in early 2008, he headed straight for the apartment. Bird called police after he pulled her hair in an argument. Again, officers made no arrest. They recorded the incident as resolved: “NPA,” for “No Police Action.”

The file does not identify the officers; it again does not explain why they failed to take Valdez Cruz into custody under the mandatory arrest law or tell why internal affairs excluded the incident from the investigation.

In April, Bird called police after Valdez Cruz punched her. Again, no arrest, no explanations, and no IA investigation of an NPA resolution.

By now Bird was desperate, her mother said. She went to court. Hoping to make him stay away from her and the children, she secured her first order of protection. But it had little effect. Valdez Cruz sneered at the threat of a misdemeanor arrest for violating such an order.

“That didn’t mean anything to us,” he said, referring to himself and suggesting that Bird, too, didn’t care.

He hounded her; police arrested him. Finally, with guns drawn, police took Valdez Cruz into custody, charged with the more serious crime of burglary after he barricaded himself in Bird’s apartment.

From jail, Valdez Cruz badgered her with ominous letters and phone calls. He told her in one call that he was going to “make her f—in’ eyes pop out [of her] f—in’ head.” She repeatedly told him that they were through. Then, in August 2008, she showed the first indication that she was resigned to a terrible fate.

“I don’t belong to anyone, and I certainly don’t belong to you,” she told him on a recorded jail call. “I don’t want to be with you. So, you’re going to kill me, whatever. Bring it on. I’m tired. I don’t want to be with you. So just finish it.”

Relentless, Valdez Cruz wrote and called.

Sometimes he begged her to stay with him.

“The only one thing that keeps me sane is knowing that I will soon see you again and maybe in time I can get my baby back ‘You Joanna’,” he wrote.

Sometimes he issued gruesome threats – to slash her face, to “f— you up real bad,” to “turn to the only thing I know and that’s violence.”

“It’s not gonna KILL you to give me one last chance. It might KILL you if you don’t,” he wrote.

On a recorded phone call, he told Bird that he would make her watch as he mutilated her genitals and that he would be upset if she died suddenly in a car accident because he wanted her to suffer.

When Valdez Cruz emerged from jail in December 2008, he had his mind made up: Bird and the two children would live with him, or else.

Bird was equally determined. She knew she had to get away.

She made plans to move out of state. She secured a new order of protection. Afraid that Valdez Cruz would come to her apartment in Westbury, she spent more time at her parents’ home in New Cassel. Terrified to be alone, she slept in Melissa’s bedroom with her sister.

“She would tell me how she really felt like she was going to die, and he was going to kill her,” Melissa remembered.

‘She would tell me how she really felt like she was going to die, and he was going to kill her.’

Melissa Johnson, Bird’s sister

Bird hid more than 100 letters Valdez Cruz had written her from jail, concealing the threatening notes under clothing in a laundry hamper in the back of a closet. She told Melissa to take the letters to the police and district attorney as evidence to prosecute Valdez Cruz if he murdered her. She believed that he kept breaking in to find them.

The day after Christmas 2008, when her murder was less than three months in the future, Bird called 911 shortly after 9 p.m. She asked police to come quickly because Valdez Cruz was beating her up.

This is the first plea for help covered by the internal affairs investigation.

Officers James Shanahan and Gary DiPasquale responded. DiPasquale knew both that Valdez Cruz had a record of domestic violence against Bird and that Bird had secured an order of protection. He told internal affairs that he assumed Valdez Cruz was the subject of the 911 call. Shanahan said that he expected “a heavy call,” meaning a serious call.

Both officers told internal affairs that a woman came out of the house, walked by DiPasquale and drove away. DiPasquale quoted the woman as saying, “He was here. He left. Everything is fine,” an apparent reference to Valdez Cruz, whose presence alone would have violated the order of protection.

The file recounts that:

Neither officer asked the woman to identify herself.

Neither stopped her for questioning.

Neither noted the car’s make or license plate number, or checked its registration, which would have identified Bird.

Neither searched for Valdez Cruz or potential witnesses.

Neither filed the state and local reports that officers were mandated to enter in domestic violence cases.

DiPasquale closed the 911 call as “UNF,” or unfounded, meaning that he had determined it was baseless.

Shanahan recorded the call as NPA.

Both designations were false, internal affairs concluded.

Total elapsed time: 13 minutes.

By then, Bird was convinced police wouldn’t help her, her family said. She told her mother, “Nobody’s going to help me.”

John Eterno, a former New York Police Department captain who heads Molloy College’s graduate criminal justice program, said that a ranking officer should have joined Shanahan and DiPasquale in responding to Bird’s 911 call, presumably ensuring that Valdez Cruz was arrested.

‘They’re basically not making an arrest where an arrest should be made.’

John Eterno, retired NYPD captain

“These officers are going to the scene. They’re basically not making an arrest where an arrest should be made, or not investigating where it should be investigated. But why isn’t there a supervisor there?” Eterno said.

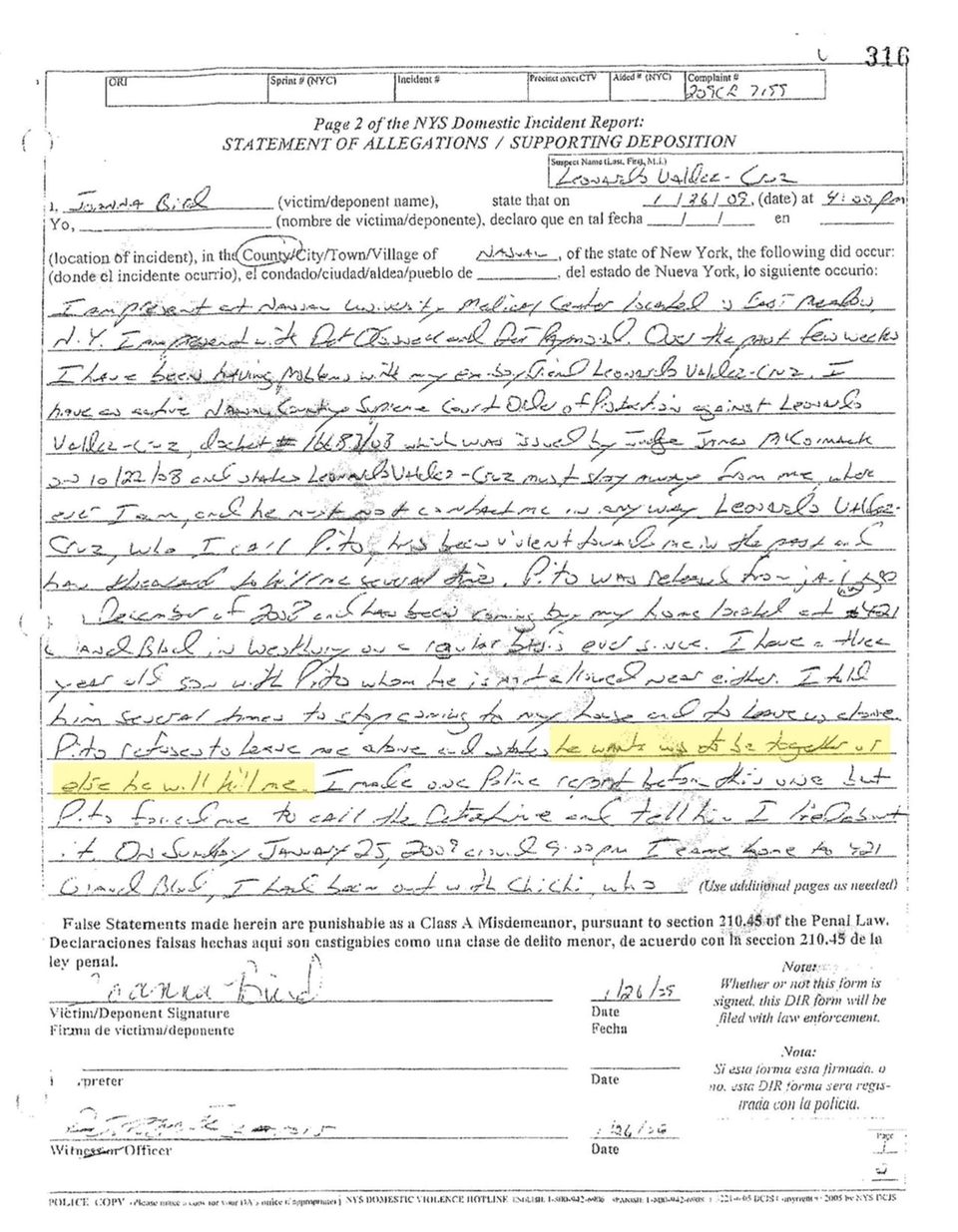

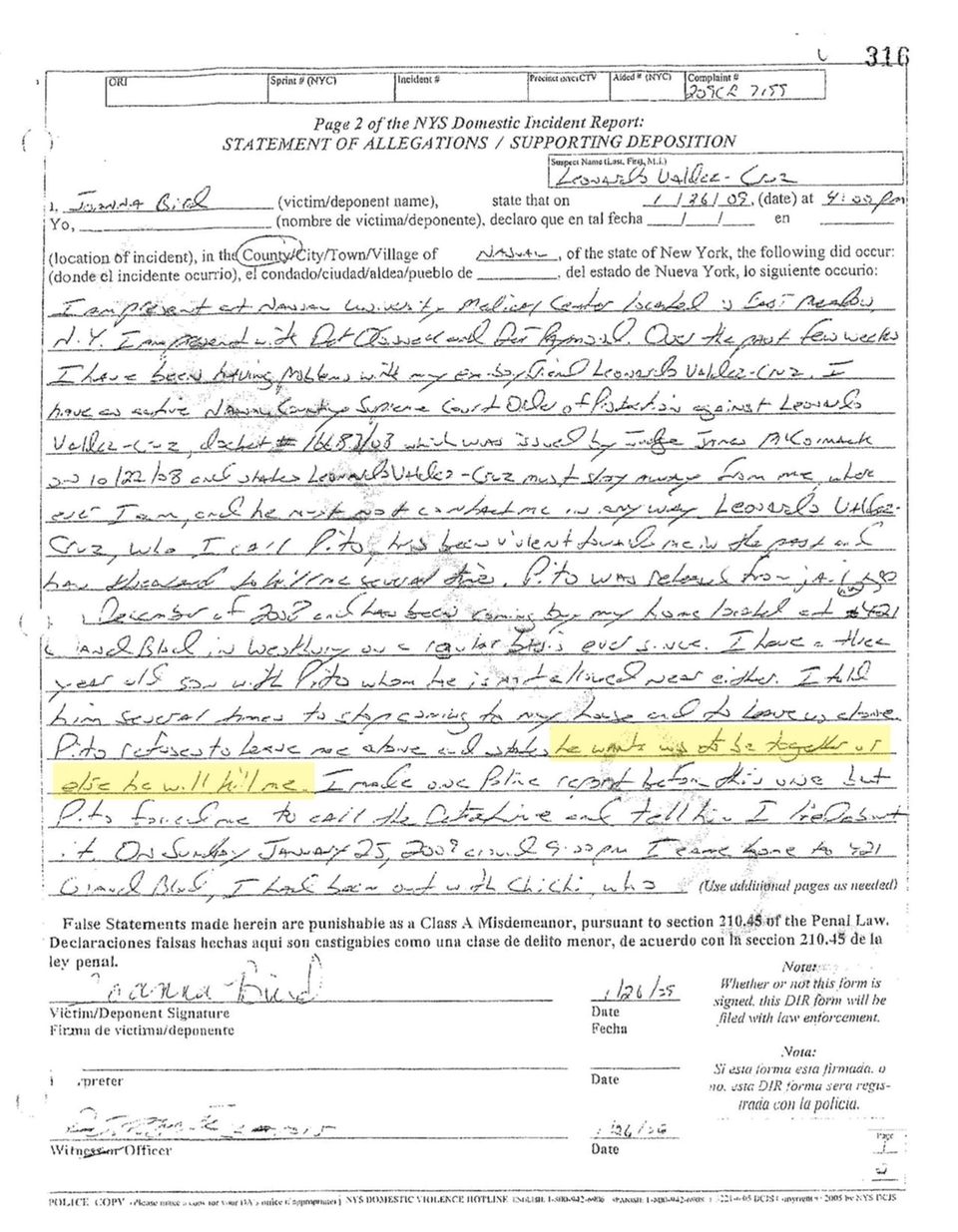

Two weeks later, Bird took what for her was a big step. She walked into the Third Precinct and asked for help.

Away from Valdez Cruz and able to speak without fear in that moment, she gave a police officer the docket number of an order of protection and signed a statement that called Valdez Cruz “my ex-boyfriend,” recounted that he had threatened her and concluded:

“I am requesting an arrest be made.”

A police officer and lieutenant signed Bird’s “Domestic Incident Report.” After an hour and 15 minutes in the precinct building, they sent her home without taking immediate action to arrest Valdez Cruz.

In fact, a detective did not follow up until three days later.

“That is completely unacceptable,” said Melba Pearson, past president of the National Black Prosecutors Association and a former domestic violence prosecutor.

“When there is an active restraining order, that usually triggers the police to act more rapidly. That is the reason why you go to court and ask a judge for this restraining order to give you that extra level of protection.

‘If the police do not respond accordingly … that defeats the whole purpose of having a restraining order.’

Melba Pearson, past president of the National Black Prosecutors Association and a former domestic violence prosecutor

“If the police do not respond accordingly and do not escalate their tactics to make sure that they’re responding quickly and in a timely manner, that defeats the whole purpose of having a restraining order.”

Det. Nicholas Occhino went to Bird’s apartment after 10:15 at night. Valdez Cruz’s sister, Aurea, stuck her head out the window and told the detective that Bird was not there. Aurea refused to come outside to speak with Occhino.

The detective asked her to give Bird his contact information and left.

Sometime after that, Bird called the Third Precinct. Occhino called her back. By then, Valdez Cruz had come to the apartment and threatened to hurt Bird. Occhino asked whether she was under duress. Under pressure from Valdez Cruz, she responded and told the detective that her account of being threatened had been false. She said that she had never actually seen Valdez Cruz at that time.

Instead, she said that someone in her neighborhood had told her the story. She refused to identify the man and refused to meet with Occhino.

“Honestly, she was terrified,” Bird’s brother Joseph said.

The police department closed the matter without additional investigation – appropriately, according to the internal affairs file.

“This investigation has determined that this Domestic incident was investigated and handled in accordance with Department Procedures,” the file concludes.

The three-day delay in responding was inexcusable, Pearson said.

“Knowing that time is of the essence, that detective should have acted immediately,” she said, adding, “Everything that you do in domestic violence cases is homicide prevention.”

A week after Bird’s trip to the Third Precinct, police received a 911 call saying that a woman was screaming. Four officers responded: Thomas Roche, Anthony Gabrielli, Brian McQuade and Brian Iovino.

Roche and McQuade were aware that Valdez Cruz had a history of domestic incidents with Bird. McQuade knew that Valdez Cruz had once barricaded himself in the apartment. Roche and Gabrielli knocked on the door. No one answered. Fearing that someone needed help, the two officers went in.

Aurea appeared and ordered the officers to leave. They continued to search the apartment while she yelled at them to get out. Roche found Bird. She was calm, said that nothing was wrong and told the officers that she hadn’t called 911.

Determining that the call had not come from Bird’s phone, the officers left the apartment. Gabrielli checked to find out whether Aurea was subject to outstanding warrants. Nothing turned up. Roche described the events to the precinct desk officer. The four officers resumed patrol.

Internal affairs concluded that officers acted properly.

A week later, Bird stopped at her Westbury apartment to pick up some things on her way to work as a school bus matron. She hadn’t been staying at the apartment. She figured it would be empty. She was wrong.

Valdez Cruz was waiting inside.

He jumped up from behind a couch and demanded that she drive him and a friend somewhere. She knew from his tone that she couldn’t say no.

After Bird dropped off the friend, Valdez Cruz put on gloves, pulled out a gun, pointed it at her, took her cell phone and keys, and said:

“This s— is going to end today. Don’t move or say anything, or I’m going to kill you.”

He ordered her out of the car. She refused. He pulled her out by her hair, opened the trunk and told her to get in.

She slammed it shut. Again, he opened it and ordered her to get in. Again, she slammed it. The third time, he threw the gun in. As he tried to force her in, she broke free and ran. He caught her, pulled her to the ground and choked her. Afraid for her life, Bird mollified Valdez Cruz by professing her love for him. He ordered her to drive back to the apartment. He spent the night with her.

The next morning, Bird dropped Valdez Cruz off at Nassau Community College, where he was starting to attend classes. Then she drove to her parents’ home and played with a baby niece. Bird’s mother noticed that something was wrong. Pulling back her daughter’s hair, she saw strangulation marks. Bird started crying.

“Jo’Anna, tell me what happened,” Dorsett remembers saying.

“He’s going to kill me,” Bird sobbed to her mother and Melissa, revealing bruising and lacerations from her hip down her leg.

Her mother and sister took Bird to Nassau University Medical Center in East Meadow. Dorsett asked security officers to call police. Det. Jeffrey Raymond came to the hospital. So did Valdez Cruz and Aurea. Valdez Cruz was a familiar face to Raymond because Valdez Cruz had given the detective information about other criminals.

When Valdez Cruz resisted arrest, Raymond tackled him. He demanded to know why Valdez Cruz was at the hospital. Aurea insisted that they were visiting her son, who was ill.

Dorsett said the police repeatedly asked Bird whether she was sure that she wanted them to arrest Valdez Cruz. She insisted. Raymond took Valdez Cruz into custody on a charge of attempted kidnapping. Valdez Cruz faced up to 20 years in prison and Bird would be freed from his domination and violence for at least as long.

What happened next became a critical turning point in Bird’s final two months.

With Valdez Cruz locked up, Bird gave police a five-page statement about his attempt to kidnap her.

‘He wants us to be together or else he will kill me.’

Excerpt from a five-page statement Bird gave police detailing Valdez Cruz’s attempt to kidnap her at gunpoint.

“We knew she was afraid of him and if she testified against him, he would hurt her,” Raymond Cote, then-commanding officer of the Third Precinct, said in a Newsday interview. “That’s why we got all these details in that statement to protect her so that she wouldn’t have to go to court initially.”

Because Valdez Cruz was being held behind bars, the Nassau district attorney’s office had up to six days to secure a grand jury felony indictment or demonstrate to a judge at a hearing that there was probable cause to believe that Valdez Cruz had attempted the kidnapping.

Both types of proceedings hinged on Bird testifying. But there was a critical difference between the two: Before a grand jury, she would testify in secret. At a preliminary hearing, she would have to testify in public – facing Valdez Cruz in the courtroom.

Valdez Cruz demanded the hearing, which was his right.

“He was arrogant, confident that she wouldn’t come forward; so, he demanded, and that’s why we had to scramble,” said Joseph LaRocca, the former assistant district attorney who handled the case.

At home with her family, Bird was convinced that Valdez Cruz would make good on his promise to kill her, Melissa said.

“They’re not going to keep him, they’re going to let him go and I’m going to die,” Melissa recalled Bird saying.

The hearing was scheduled for Feb. 2, 2009. Bird failed to appear, as did Raymond.

Police searched for Bird. They couldn’t find her.

Valdez Cruz had been calling from jail. He told Bird that he would kill her if she talked to the police, her mother said. In his prison interview, Valdez Cruz maintained that Bird had simply chosen not to testify “because she didn’t want to see me going to jail.”

Without evidence that Valdez Cruz had intimidated Bird, the DA’s office had to order his release, LaRocca said.

“The only evidence was her. She gave the statement describing it. There were no witnesses, the defendant never confessed, or made a statement. There was no video or camera,” he said.

“And when she wouldn’t come forward, that’s why, by law, he was released.”

Cote contacted domestic violence advocates to help Bird. Speaking with Newsday, he remembered directing Raymond to give LaRocca a chilling warning:

“Let him know if you let this guy out, he’s going to kill her.”

Raymond offered Bird the use of a “panic button” that would instantly alert police that she was in danger. She declined it, according to the file. He also offered to help relocate her. She declined that as well, the file says.

Cut loose, Valdez Cruz became emboldened.

He bought Bird an engagement ring and proposed marriage in front of her mother. Bird refused. Valdez Cruz turned cold.

“If you don’t marry me, you won’t marry anyone, because I’ll kill you,” he told her, Dorsett recalled.

He went to the homes of her friends, warning that he would kill her if she left him. He showed up when she ran errands, watching from behind the wheel of a yellow Cadillac. By March, he called her 40 to 50 times a day.

“If you’re not going to be with me, you’re not going to be with anyone,” he told her, according to Sharon’s testimony at the homicide trial. “Keep playing with me. I’m going to kill you. You’re going to be dead, bitch.”

One morning, as Bird was leaving for her job as a school bus matron around 6 a.m., he jumped up from behind her car, demanding to talk to her and yelling, “I’m not playing with you.”

Her mother began walking her to her car. And Bird made plans to move away.

BIRD’S LAST FOUR DAYS

After midnight leading into March 15, 2009, Valdez Cruz’ obsession became a police matter again. He appeared at Bird’s parents’ house three times to insist that she come home with him. If she didn’t, he made clear there would be consequences. She refused.

The family called 911 three times, hoping that police would arrest Valdez Cruz. They didn’t.

A little after 1 a.m., Melissa heard a muffled scream. She ran downstairs and saw Valdez Cruz with a pillow over Bird’s face on the couch. He jumped up. Melissa ran to call 911.

“He’s got a knife!” Bird screamed.

Officers Christopher Acquilino and Steven Zimmer responded to the emergency call. A woman met them at the door, according to the file. That woman was Bird. She and her family told the officers that she had an order of protection. They pressed the officers to check. They did not. They only ordered Valdez Cruz to leave.

Acquilino and Zimmer drove away without having taken the basic step of asking for Bird’s name.

They told internal affairs that no one said anything about a knife or the existence of an order of protection.

Total elapsed time: 5 minutes.

Internal affairs discovered that the two officers were then “out of service” for the next 46 minutes, meaning the police department had no record they were on patrol for that time. They told internal affairs that they knew nothing about Valdez Cruz and that the woman at the door assured them that all was fine. There is no indication that internal affairs investigated what the two officers had done during the missing 46 minutes.

An hour later, Valdez Cruz barged into the house again, now with Aurea. Bird’s stepfather, Vernard Johnson, ordered Valdez Cruz to leave and called 911. Acquilino and Zimmer returned, accompanied by Officers Joseph Massaro and Thomas Shevlin in a second patrol car.

As the four officers approached the front door, Zimmer told Massaro and Shevlin, “We’ll handle this. We were here earlier,” according to the file.

Again, Bird and family members told the officers that Bird had an order of protection. Bird also said that Valdez Cruz had chased her with a knife, four of the family members told internal affairs.

Acquilino, Zimmer, Massaro and Shevlin acknowledged to internal affairs that they told Valdez Cruz and Aurea to leave without identifying them, had not investigated their presence in the house and did not check whether there was an order of protection. All four said they heard nothing about a knife or about an order of protection.

Total elapsed time: 5 minutes.

As Valdez Cruz recalled it, “I’m out there like, ‘Whew. That was a close one.’ I know that they were supposed to do their job. But they didn’t.”

Terrified, Bird went to sleep in her parents’ bedroom.

Around 5 a.m. Valdez Cruz climbed through a bathroom window in full view of Melissa. She called 911. Valdez Cruz fled.

Acquilino and Zimmer handled the call again.

The family reported that Valdez Cruz had broken in, committing attempted burglary, a crime that could have landed him behind bars for an extended period. As proof, the family showed the officers a hat that Valdez Cruz had dropped in the bathtub.

Still, Acquilino and Zimmer did not enter the house or check for an order of protection. They also failed to put out an alert about an attempted burglary by a named individual.

In their memo books, Acquilino and Zimmer wrote “condition corrected.” The internal affairs file did not note the elapsed time of the call. The officers then went out of service for 82 minutes. They asserted to internal affairs that they were hunting for Valdez Cruz while they were off the radar screen.

At his murder trial, Singas told the jury that the officers’ failure to act emboldened Valdez Cruz by letting him go without consequences.

Two days later, Valdez Cruz took Bird’s car and made an illegal U-turn over a double yellow line. Officer Anthony Gabrielli pulled him over.

“I don’t have no license. It’s revoked. I shouldn’t be driving,” Valdez Cruz said.

Officer Thomas Roche arrived as backup. Immediately, Valdez Cruz asked to speak with Raymond, saying he had information about a man named Pookie who was selling guns and drugs in Westbury.

After that statement, Gabrielli became the first of three officers who enabled Valdez Cruz to further torment Bird with impunity. He drove Valdez Cruz to the precinct, without impounding Bird’s car as legally required. He failed to identify Bird as the car’s owner and failed to check on an order of protection, which could have led police to arrest Valdez Cruz.

Additionally, he falsely told his supervisor, Sgt. Kenneth Ward, that he was going to release the car to its owner. Then, he falsely punched into the police department’s computer system that he had released the car to its owner, rather than investigate the possibility of arresting Valdez Cruz for driving a stolen car.

At the precinct, Gabrielli and Roche searched Valdez Cruz and confiscated his cell phone.

Raymond, the arresting officer when Valdez Cruz attempted to kidnap Bird, well knew Valdez Cruz’s history with Bird, his violent streak and the threat of arrest he faced for violating an order of protection. Precinct security cameras showed that he met with Valdez Cruz in a cell for 25 minutes.

Valdez Cruz named Bird’s brother, Jonathan, as the man who had robbed a New Cassel pizzeria at gunpoint, according to the internal affairs file.

In his interview with Newsday, Valdez Cruz denied giving Raymond any information about Jonathan Bird. He said he merely offered to help Raymond, so he could get released: “You let me go now, I’ll try to go over there and find him and see if he’s at the house and tell him to turn himself in. They let me go.”

After the 25-minute conversation, Raymond gave Valdez Cruz the confiscated cell phone in violation of department regulations. Valdez Cruz started calling Bird, each call violating an order of protection.

Gabrielli took the phone away.

Raymond returned the phone to Valdez Cruz.

Roche admitted to internal affairs that he saw Valdez Cruz using the cell phone in the detention cell and that he did not take it away from Valdez Cruz. He also said that he did not know Valdez Cruz had called Bird, according to the file.

All told, Valdez Cruz made 80 calls while in the precinct – 46 of them to Bird.

Raymond later told internal affairs that Valdez Cruz had provided information about guns and drugs, as well as about Jonathan Bird. He also said that he took a photo array that included Jonathan Bird’s picture to the pizzeria, where witnesses identified him as the robber. Eventually, Jonathan Bird was convicted and sentenced to prison.

The detective explained that he let Valdez Cruz make calls for “investigative reasons” and had simply forgotten to take it back from him.

Standard processing called for Valdez Cruz to be held overnight for arraignment in court in the morning. Raymond worked out a better arrangement for him.

Police have the power to release people using what’s called a Desk Appearance Ticket, essentially a summons to appear in court. These DATs are typically reserved for people who have been charged with low-level offenses and who are not repeat offenders – or, for example, a member of the Bloods.

To win release for Valdez Cruz, Raymond asked his supervisor, Sgt. Ward, to take Valdez Cruz’s cooperation into account. He did not inform Ward about Valdez Cruz’s criminal record, violent history and the orders of protection against him, the file states. It also shows that Ward approved letting Valdez Cruz go with a DAT without confirming Raymond’s information, as he was required to.

Raymond dropped off Valdez Cruz at Bird’s car. He told internal affairs that he watched to make sure that Valdez Cruz then went on his way without driving the car.

“This guy’s a known gang felon,” Eterno said. “You can’t just release him back out there knowing that he is involved in this domestic incident.”

Valdez Cruz went straight back to Bird.

Forty-four minutes after his release, the family called 911. Officers Jason Contino and Christopher Jata arrived to find Valdez Cruz banging on the door of her mother’s house. With Valdez Cruz nearby, Bird told the officers that he had come to the house not knowing she was there.

Bird was torn. By now she was convinced that the police wouldn’t protect her, and she was terrified that Valdez Cruz would make good on his promise to kill her sister and her mother, Melissa said.

Without additional investigation, Contino and Jata gave Valdez Cruz a pass. Once again, police did not make an arrest, as required by New York’s mandatory arrest law.

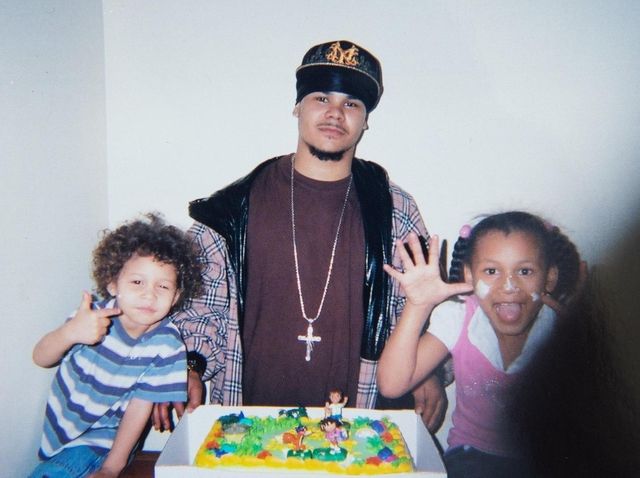

The next day – the day before her murder – Bird and the family celebrated her daughter’s 6th birthday. Valdez Cruz insisted on being there. To appease him, Bird agreed. Home video showed Bird looking strained as she stood near him at the party. Aurea came with her brother.

Valdez Cruz and Bird with her children at a birthday party the night before he killed her.

After singing Happy Birthday, Valdez Cruz sat down next to Bird and again made his intentions clear:

“You better come home with me,” he told her, according to trial testimony. “I’m not playing.”

Bird didn’t go. Within 24 hours, she would pay with her life.

THE HOMICIDE

At the party, Aurea asked to borrow Bird’s car. Bird agreed, but said she needed it back that night because she had to go to her job as a school bus matron by 6:30 a.m. the next day, March 19, 2009. Aurea didn’t return the car as promised, so Dorsett drove Bird to work.

Meanwhile, Valdez Cruz was on the hunt. He called Bird 37 times by 9:32 a.m., when the calls stopped.

Around that time, Aurea pulled up in the parking lot of the bus terminal. Valdez Cruz hid low behind the backseat. Bird didn’t see him when she got into the car. Then she discovered that she was at the mercy of Valdez Cruz and Aurea.

They drove to Bird’s apartment. She had less than three hours to live.

The only record of what happened before Valdez Cruz’s fatal spasm of violence is that he deposited semen into her body that morning, according to the medical examiner.

At 12:34 p.m., Dorsett received a call that she dreaded and will never forget.

‘Mommy, help! Please help me, Mommy.’

-Sharon Dorsett, Bird’s mother, says these are the last words her daughter spoke to her

“Mommy, help me! Help me!” Bird screamed into the phone. “Pito is in the house. I can’t get out! He has me locked in. He has me trapped. Mommy, help! Please help me, Mommy.”

In the background, Dorsett heard Valdez Cruz say, “You be dead before your mother or the police get here.”

Dorsett and Melissa raced the two miles to Bird’s apartment, as Melissa called 911.

Police arrived within minutes and surrounded the house, but didn’t go in. They banged on the door and called Bird’s phone. There was no response. Family members later claimed in their lawsuit that police delayed responding with potentially deadly consequences. The police department denies their assertions and released records showing a fast response.

Emergency Services Unit officers arrived about 15 minutes later at 1 p.m. Because they believed Valdez Cruz could be holding Bird hostage, they waited for a hostage negotiator, a police spokesman said then.

Over the next frantic minutes, Valdez Cruz stabbed Bird so many times that the medical examiner couldn’t give an exact count of the wounds. Valdez Cruz twisted the knife in her throat, transecting her windpipe.

And, keeping with a vow he had made in a letter, Valdez Cruz stabbed Bird around the eyes while she was still alive.

Outside, Officer Daniel Doerrie noticed Melissa crying and pointing to Aurea, who was talking on her phone, bent over as if she were going to vomit.

“You got to tell me what’s going on,” Doerrie told Aurea.

“She’s in the house, and she’s no longer alive,” Aurea answered.

Police burst in. Valdez Cruz had propped her body on the steps of a stairway to the second floor. There were signs that she had tried to run for her life. A bloody clump of her hair and blood streaming down the steps suggested Valdez Cruz had dragged her there before fleeing out the back of the building.

He made his way to the Bronx, where his father lived. Under police pressure, Aurea revealed where he was. Police found him the next day.

“Am I going to spend the rest of my life in jail?” he asked.

THE TRIAL

Madeline Singas, who was then chief of the sex crimes unit, prosecuted Valdez Cruz. She went on to become Nassau County district attorney. Nominated by former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, she took a seat on the New York Court of Appeals, the state’s highest bench, in June. She declined interview requests.

Valdez Cruz pled not guilty and went to trial. His only prayer of acquittal was that the police had not found him at the scene, leaving open the possibility that someone else was the killer.

Singas immersed the jury in the horror of Valdez Cruz’s relationship with Bird and frankly confronted the police department’s failures to arrest him. In her closing argument, she reminded jurors that Valdez Cruz had vowed to make Bird’s eyes “pop out” and make her “sit up” while he killed her.

“She is sitting here trying to make me look guilty,” Valdez Cruz shouted, jumping from his seat. “I did not do this crime. “

Admonished by the judge, he asked, “What about my feelings?”

Jurors deliberated for almost two days. In a Newsday interview, jury forewoman Karen Brandon said cell tower records convinced the panel that Valdez Cruz had been at the murder scene. And the letters he had written from jail had laid out exactly what he planned to do – just as Bird had predicted to Melissa when she asked her sister to hide them.

‘I could never understand, why did they let him go? Each time. It just, it boggles my mind.’

Karen Brandon, jury forewoman in the case

Reece T. Williams

“It was probably one of the most challenging experiences of my life to hear the brutality and intensity of their relationship,” Brandon said. “It changed me. It absolutely changed me.”

The police failure to arrest Valdez Cruz, particularly on the night when the family called 911 three times, puzzled all the jurors, she said.

“I could never understand, why did they let him go? Each time. It just, it boggles my mind. You know, and subsequently we were able to discuss it as a jury – we were all like why is that?” she said.

Brandon and other jurors attended the sentencing.

“We wanted to do it,” she said, “for Jo’Anna.”

VALDEZ CRUZ IN PRISON

Locked away for life without hope of parole, Valdez Cruz opened an interview in August in the Green Haven Correctional Facility by explaining, “I’m just not, trying to just completely look like a bad guy, like they been portraying me.”

He maintained that lying witnesses and corrupt cops had steered his trial to a wrongful conviction, and he cast guilt for Bird’s homicide onto unknown robbers or drug dealers. He brought notes to the interview, as well as family photographs, but no proof of his innocence.

Reminded that in a letter shown to his jury he had told Bird she “was going to have to sit up while you stabbed her to death,” just as happened to her, Valdez Cruz answered calmly:

“This is what the district attorney does. This is their job. To make, to take things and turn it into a big Picasso and make it look bigger than it really is.”

Valdez Cruz, now 36, wore a green prison jumpsuit, white knit cap and glasses to the interview. He was not handcuffed or shackled, but a corrections officer stood close by during a nearly 90-minute socially distanced conversation.

He admitted being violent towards Bird, kidnapping her and repeatedly violating her orders of protection; he blamed his behavior on his addiction to PCP. He described a childhood in a fatherless household, toughening stints in juvenile facilities and early involvement in crime.

At no point did he take responsibility for his actions, saying instead that he had been consumed by “this game we call life on the streets.”

His depiction of his relationship with Bird was wildly at odds with all the evidence.

He was particular about how his record would be reported, disputing that he had been classified as a violent felon before Bird’s murder. There he was right. After he slammed the 11-year-old bike rider to the ground and pummeled the boy, police had charged Valdez Cruz only with a misdemeanor.

He described much of his life as a series of failures that often were the fault of others, or of drugs.

“As much as I tried to do right, it just, it’s like bad always befell me,” he said. “No matter which road I tried to take, it was like, it was just I always ended up in a dead end.”

And he talked about police, including Det. Raymond, from a street-gang point of view. He insisted, strongly, that he had never provided useful information about other criminals to anyone in law enforcement.

Including Raymond, the detective found to have enabled Valdez Cruz to violate Bird’s order of protection.

Including information that pointed police toward Bird’s brother as a suspect in a pizzeria robbery.

“My relationship with Detective Raymond and the Nassau County Police Department is the same as every criminal out there doing crime who gets arrested,” Valdez Cruz said. “I can’t stand him. And that was it.”

Reminded that he had asked to speak with Raymond after getting arrested for driving Bird’s car without a license (an arrest that took place two days before Valdez Cruz murdered Bird) Valdez Cruz said:

“I utilized Detective Raymond the same way he tried to utilize me. In this game we call life in the streets, you’re going to have detectives and officers that if they know who you are and who you are associated with, it doesn’t matter if you get locked up for stealing a lollipop out of 7-Eleven …

“So, I was telling Raymond and the detective who locked me up, what they wanted to hear. I do that all the time. No, so there’s nothing wrong with that. As many times as I’ve been in the precinct, and they put hands on me, and they assaulted me and they threatened me, and they overcharge me for things and they got over on me, why can’t I get over on the police department if they’re going to allow it?”

Emphatically, he added: “There’s not an individual walking God’s green Earth today that says Leonardo Valdez Cruz put me in prison.”

His criticism of the police extended to their failure to arrest him for violating Bird’s orders of protection.

“They’re just being lazy,” he said. “And they didn’t care.”

As the interview was closing, Valdez Cruz acknowledged that he looked healthy.

“I try to eat and work out and stay focused and stay busy because my goal is to try to find a way to make it home one day and reconnect with my children,” he said, admitting that he has no contact with the son he fathered with Jo’Anna and the daughter she had with another man.

“You know, they don’t want to have anything to do with me,” he continued. “For the years of negative things that was placed into their head through their grandmother and that side of the family. And I understand. You know, but I just want them to know that I love them.”

FAMILY AFTERMATH

He is 16 years old and a student at Hicksville High School, where he’s a point guard on the basketball team. Family, friends and school officials say he’s a happy-go-lucky guy and is thriving.

But he’s haunted by the sound of his full given name.

He was named after his father – the father who killed his mother, the murderer, Leonardo Valdez Cruz.

He looks forward two years to the age when he will gain the legal power to change his name.

Until then, he is to be called Leo, not Leonardo Valdez Cruz.

Bird’s daughter, Nana, remembers police coming to school when she was just six years old, and bringing Leo and her to their grandmother, Sharon Dorsett. They found Dorsett, Bird’s mother, weeping.

“She was like, ‘She won’t be coming back.’ And she said that she went away to a better place,” Nana, now 18, recalled, through tears.

Leo Antonio Valdez and Nana Bird. Photo credit: Jeffrey Basinger

For Leo, being asked to recall that moment is like a gut punch. At the mention of it in an interview, he doubled over, buried his head in his hands and sobbed.

The pain and grief over Bird’s death is still raw for the people who loved her.

“He took something from us,” Bird’s sister Sharon said. “And I hate him for it. I hate him for it, and I know it’s not good to hate. But I hate him for it. Because he’s still breathing. He still gets to watch the TV. He still gets to eat… He talks to people. He sees letters from people, and it’s not right. And it’s not fair.”

Told that Newsday had obtained the internal affairs file, Bird’s loved ones described in interviews the continuing reverberations of her murder in their lives.

They feel anger, not just toward the man who murdered her, but also toward the police they believe didn’t do enough to protect her. Worse than the anger, however, is the guilt. They said they are haunted by thoughts that, maybe, they could have done more to shield her from Valdez Cruz.

Bird and her siblings formed a close-knit yet fractious family; some of their fights prompted 911 calls. Brothers Jonathan and Joseph have both served time in prison. But the family is united in believing that a key reason police failed to stop Valdez Cruz from targeting Bird was that he was an informant.

“They knew his track record and what he’s done, his domestic record,” Joseph said. “And she’d call the police for months and days and telling them this was going on. I’ve got an order of protection and they still let him out.”

Referring to the police, Bird’s brother Walton, known as Junior, added, “They made a mistake, a fatal mistake” by deciding that letting Valdez Cruz stay “free is worth more than her life.”

Twelve years later, family members look back with a terrible what-if question: What if they had only done something more?

“I feel like I failed because I feel like we should have been there that day and this would have never happened,” her sister Sharon said, recalling the day of the murder.

Bird’s family knew that Valdez Cruz had been abusive, and they knew she was frightened. But, busy with their own lives and reassured when she told them she was fine, they didn’t step in.

Junior, who had been living with Bird, remembers telling her that he was moving out to live with his girlfriend and young child. He didn’t realize it at the time, but he was, in effect, leaving her to face Valdez Cruz more on her own.

“The look on her face, when I turned around, that turned me around and I went back up the stairs, and asked her, ‘What’s wrong? What’s going on?’

“Because I felt a vibe, the energy that something was wrong. But I felt like she didn’t want to tell me. I felt like I should have stayed there.”

The night before Valdez Cruz killed Bird, Joseph sensed something wrong. She seemed distressed but wouldn’t talk about it. He told her he loved her and that he didn’t want to lose her. Today, it tears at him that he didn’t act.

“I feel guilty that I didn’t protect her that night, and I let her go back, to leave my sight, to go back to the house,” he said.

Bird’s siblings believe she stayed silent to make sure they were safe from Valdez Cruz. He had threatened to kill them; she knew that he was capable of violence. He had made his violent intentions all too clear in the threatening letters she had hidden so that, if need be, she could tell the truth about Valdez Cruz from the grave.

“She said, ‘If something was to happen to me, you’re the only one who knows where the letters are,” Bird’s sister Melissa said. “So, if something happens to me, give them these letters. So, when she got killed, I told the DA where the letters were.”

In 2012, Nassau County agreed to pay Bird’s family $7.7 million as compensation for the police department’s failure to protect her. The money came tinged with sorrow and even some reproach from others.

“I had a guy in Babies ‘R’ Us approach me. Yelling and screaming at me,” Bird’s mother, Sharon, recalled. “I was on line and I was paying for a gift for a baby shower and he starts yelling and screaming at me. ‘Who do you think you are?’

“And I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ He said, ‘Your daughter is dead. She’s gone.’ He said, ‘Why are you trying to make these officers suffer? Do you know they got families and they have kids?’ And I turned around and I said, ‘I’m sorry.’”

Valdez Cruz repeatedly petitioned in court for visitation rights with Nana and Leo. After multiple hearings, where Sharon Dorsett refused to look at Valdez Cruz in the courtroom, a judge denied him. Nana and Leo want nothing to do with him.

They have been raised by her parents, who are both protective and proud of them.

Nana has graduated from Hicksville High School and plans to study cosmetology and start her own business.

Leo hopes to become a personal trainer after graduating.

For Melissa, in particular, who idolized her older sister, the years after Bird’s murder have been an emotional struggle. She cries when she looks at family photos. After the birth of her third child, she suffered postpartum depression and “wanted to go be with Jo’Anna,” she said.

Her mother and her own children helped Melissa recover.

She worried that an interview could drag her back into depression but felt something important was at stake for other “families who had to go through losing a loved one to domestic violence.”

She spoke with the hope of making people “aware of how serious domestic violence is and how a lot of these women (are) being failed.”

“I’m crying,” she wrote in a text, “while writing this.”

Reporter: Sandra Peddie

Editor: Arthur Browne

Video and photo: Jeffrey Basinger, Howard Schnapp, Chris Ware, Reece T. Williams

Aerial Photography: Jeffrey Basinger, Kevin P. Coughlin

Video editors: Valerie Robinson, Jeffrey Basinger

Studio graphics: Gregory Stevens

Documentary writer: Pat Dolan

Documentary production: Jeffrey Basinger, Robert Cassidy, Pat Dolan, John Keating, Sandra Peddie

Studio Production: Mike Drazka, Faith Jessie, Arthur Mochi Jr., Gregory M. Stevens

Digital producers: Heather Doyle, Tara Conry, Joe Diglio

Digital design/UX: James Stewart

Social media editor: Gabriella Vukelić