Suffolk County District Attorney Chief Aide Christopher McPartland

Convicted of:Conspiracy, obstruction of justice, witness tampering and acting as accessories to the deprivation of the civil rights of Christopher Loeb, a suspect in the break-in of Suffolk Police Chief James Burke’s department SUV

Christopher McPartland, one of Suffolk County District Attorney Thomas Spota’s chief aides, who ran the office’s political corruption unit, was indicted along with Spota in October 2017 on federal charges related to allegations the two were involved in a cover-up of ex-Suffolk Police Chief James Burke’s assault of a suspect. McPartland pleaded not guilty to the charges. McPartland was fired by incoming District Attorney Timothy Sini and left the DA’s office as of Dec. 31, 2017, according to spokesman Justin Meyers. Spota and McPartland’s trial began on Nov. 12, 2019. Spota and McPartland were convicted on all counts on Dec. 17, 2019. On Aug. 10, 2021, McPartland was sentenced to five years in prison. Spota was also sentenced to five years.

The latest on McPartland’s case

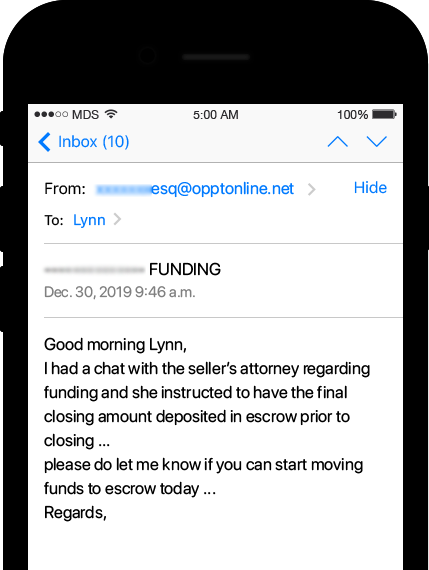

Aug. 10, 2021: Spota, McPartland each sentenced to 5 years in prison Aug. 8, 2021: Spota, McPartland to learn their fates at sentencing scheduled Aug. 5, 2021: Spota, McPartland face 57 to 71 months in prison under federal sentencing guidelines, judge rules June 30, 2021: Spota, McPartland defense teams argue against possible sentence enhancements May 1, 2021: Unsealed Spota records reveal allegations of plot to topple Levy April 17, 2021: Feds: Spota and McPartland should serve 8 years in prison for Burke cover-up March 9, 2021: Spota, McPartland should not go to prison over Burke cover-up, court papers say Feb. 25, 2021: Federal judge in Spota-McPartland criminal case said she would unseal some court records Dec. 10, 2020: Judge sets Spota, McPartland sentencings for March 24 Nov. 30, 2020: Judge refuses to toss Spota-McPartland convictions; defendants won’t get new trials July 1, 2020: Feds, defense clash over sentencing date for ex-Suffolk DA Spota June 10, 2020: Former Suffolk DA Spota disbarred from practice of law due to conviction May 28, 2020: Spota, McPartland sentencing delayed again due to coronavirus May 5, 2020: Defense for ex-DA: Prosecution brushed off defense bid for new trial April 13, 2020: Defense, prosecution spar on bid for new trial for Spota, top aide March 9, 2020: Suffolk sues Spota, McPartland and Burke for back pay and benefits Feb. 28, 2020: Papers: Spota, McPartland want convictions thrown out; seek new trial Feb. 12, 2020: Sentencing delayed for former Suffolk DA Jan. 10, 2020: Bellone: Spota conviction closed ‘dark chapter’ in Suffolk history Jan. 7, 2020: Sentencing set for April for Spota, McPartland Dec. 17, 2019: Jury finds Thomas Spota, Christopher McPartland guilty Dec. 16, 2019: Spota-McPartland jury sends 3 notes to judge as deliberations start Dec. 16, 2019: Power on Trial: Judge mentions Burke 45 times in jury instructions Dec. 12, 2019: Defense: No credible evidence ex-DA Spota was corrupt Dec. 11, 2019: Power on Trial: Defendants formed a cabal, prosecutor says Dec. 11, 2019: Lawyers sum up in Spota, McPartland obstruction trial Dec. 10, 2019: Power on Trial: James Burke’s lawyer takes the stand Dec. 10, 2019: Ex-chief’s lawyer at trial: Burke wanted it known he didn’t cooperate Dec. 9, 2019: Power on Trial: Burke brother says guilty plea was ‘tough pill’ Dec. 9, 2019: Witness: McPartland took jailed ex-PD chief’s money without questions Dec. 5, 2019: Power on Trial: Ex-Spota deputy says Burke trash-talked DA’s office Dec. 5, 2019: Ex-DA’s deputy: Spota had a ‘queasy’ feeling about chief’s comment Dec. 4, 2019: Power on Trial: Burke cried at Spota’s home, witness says Dec. 4, 2019: Former top prosecutor says ex-DA was angry at handling of beating case Dec. 3, 2019: Power on Trial: McPartland, Spota lawyers quiz ex-cop Dec. 3, 2019: Defense for ex-DA Spota attacks star government witness Dec. 2, 2019: Power on Trial: Ex-cop feared for safety in Burke meeting Dec. 2, 2019: Ex-cop testifies he feared for life as beating cover-up unraveled Nov. 26, 2019: Power on Trial: Ex-cop links McPartland, Spota to cover-up Nov. 26, 2019: Witness: Spota demanded to know who ‘flipped’ on Burke cover-up Nov. 25, 2019: Power on Trial: Stress over Loeb probe put cop in hospital Nov. 25, 2019: Doctor: Key witness in Spota case hallucinated after stress, no sleep Nov. 21, 2019: Power on Trial: A brutal beating described Nov. 21, 2019: Witness: Burke’s fury sparked by prisoner’s ‘pervert’ insult Nov. 20, 2019: Power on Trial: Cops describe department in turmoil Nov. 20, 2019: Ex-detective testifies he put family in hotel due to concerns about Burke case Nov. 19, 2019: Power on Trial: Current and former cops take the stand Nov. 19, 2019: Detective: Burke’s bag contained sex toys, condoms, union cards Nov. 18, 2019: Power on Trial: Suffolk Dems leader takes the stand Nov. 18, 2019: Schaffer: Spota boosted Burke’s bid for chief job Nov. 14, 2019: Power on Trial: Spota, McPartland trial gets underway Nov. 14, 2019: Feds: Spota, McPartland thought they were above the law Nov. 13, 2019: Jury selected in case against former Suffolk DA and aide Nov. 12, 2019: Key figure appears at final jury selection round in Spota-McPartland trial Nov. 9, 2019: Former DA Spota’s obstruction trial to start Tuesday Nov. 5, 2019: Jury selection moves forward in case against Spota, McPartland Oct. 30, 2019: Hundreds of potential jurors screened for Spota/McPartland trial Oct. 2, 2019: Judge denies defense request for Spota, McPartland trial delay Sept. 11, 2019: Lawyers: Ex-Suffolk DA, aide committed no crime June 27, 2019: Judge sets trial schedule for ex-DA Spota, aide April 1, 2019: Judge delays the Spota-McPartland trial to November March 11, 2019: Bellone signs bill to recoup Burke pay; targets Spota Dec. 6, 2018: Prosecutors: Spota, top aide plotted to obstruct justice Oct. 25, 2018: Judge delays obstruction trial of Spota, aide to May June 20, 2018: Prosecutors turning over evidence in Spota-McPartland case, government says June 11, 2018: Christopher McPartland gets legal defense fund June 2, 2018: Brown More corruption trials on Long Island are to come April 12, 2018: Power on Trial: Judge in Mangano trial also presiding over Spota case April 12, 2018: Judge gets Spota trial date for March, 2019 Jan. 26, 2018: Spota, former aide make brief court appearance in cover-up case Dec. 23, 2017: Arc of Thomas Spota’s career marked by close relationship with police Dec. 1, 2017: Thomas Spota’s aide wants government to pay for current attorney Nov. 21, 2017: Records: Suffolk DA’s office bonuses totaled $3.25M since 2012 Nov. 15, 2017: Brown: Restore trust in Suffolk DA’s office — now, not later Oct. 28, 2017: Brown: Thomas Spota couldn’t continue as Suffolk DA Oct. 26, 2017: Spota, McPartland draw mix of onlookers to courtroom Oct. 26, 2017: Suffolk DA Thomas Spota, top aide indicted in cover-up June 11, 2016: Sources: Probe focuses on Thomas Spota, Christopher McPartland Feb. 7, 2016: Feds probe if Suffolk wiretap violated civil rights, sources say Jan. 10, 2016: Chris McPartland, Spota deputy, sought Internal Affairs files on James Burke, sources say Jan. 7, 2016: Christopher McPartland, key aide to DA Thomas Spota, investigated by federal grand jury, sources say