The damaged Long Beach Boardwalk two and a half months after Sandy. Newsday / Alejandra Villa

The $102 million in state and federal emergency disaster funds given to Long Beach after superstorm Sandy masked financial problems that, with the relief money now drying up, led the city into a fiscal crisis, officials and analysts say.

Long Beach faces a $2.1 million shortfall after making retirement and management separation payments, potential layoffs of city staff, police and firefighters, and a budget that proposes a 12.3 percent tax hike to bridge a $4.5 million revenue deficit next year.

Taxpayers — and state Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli — are asking: How did it come to this?

Long Beach officials in 2017 touted a financial swing from the brink of bankruptcy to being $9 million in the black — a $24.2 million turnaround — but current and former city leaders say the previous collapse was never addressed and stayed hidden because of the disaster relief funds after superstorm Sandy.

“We’re almost where we were before Sandy,” Long Beach City Council President Anthony Eramo said of the current crisis. He also said problems the city faced before Sandy have not gone away. “We knew this would be a tough year and hard decisions would have to be made. . . . I knew the lack of Sandy money would make this a tough year.”

Eramo, DiNapoli, and municipal finance analysts say city officials should have made more difficult decisions such as cutting services and making incremental tax increases in previous years to avoid the larger tax increase proposed this year. The City Council passed a 1 percent tax boost last year — an election year.

The proposed $95 million budget for the fiscal year starting July 1 will mean an average $400 increase for homeowners.

DiNapoli announced last week that his office would audit the city’s finances.

“It is imperative that officials address the city’s declining financial condition during the current budget cycle,” his office said in the annual budget review.

“It’s identical to putting your budget on a credit card. It’s not a sustainable practice.”-Matt Fabian, a partner with Municipal Market Analysts.

The Wall Street bond rating agency Moody’s Investors Service this month maintained the city’s Baa1 rating — considered a moderate credit risk, but issued a negative outlook, citing cash flow challenges “following years of operating deficits and the City Council’s failure to approve budgeted borrowing to pay for operating expenses.”

Lower ratings can mean higher interest rates and costs of borrowing.

“Any time a local government borrows for operating expenses, we view that as a negative,” Moody’s vice president and senior analyst Rob Weber said.

Long Beach has borrowed to cover retirements and other payments for years.

“It’s identical to putting your budget on a credit card,” said Matt Fabian, a partner with Municipal Market Analysts, a municipal research and consulting firm specializing in the bond market. “It’s not a sustainable practice.”

Elements of the current fiscal crisis mirror those in 2011: unbalanced budgets, borrowing to make payroll and separation payments, and reliance on storm relief funding.

Former City Manager Jack Schnirman and the Long Beach City Council declared a fiscal emergency in 2012 after inheriting a $14.7 million deficit and facing $48.3 million in debt from the previous administration.

Long Beach was on the brink of bankruptcy as ratings agencies downgraded it five levels and threatened to reduce its credit to junk bond status. Other city officials faulted the administration for not reining in overtime and relying too heavily on reserves while giving residents a 1.9 percent tax cut in 2009.

The administration responded with a nearly 8 percent tax hike in 2012 and entered a deal with the state to pay the debt over 10 years, which allowed the state comptroller to review the city’s budgets annually for the next decade. The city’s total long-term debt is now $92.2 million.

An audit in 2013 by DiNapoli blamed the city administration for exhausting $21 million in reserve funds with “unrealistic estimates” of revenue and expenses and relied on advances and long-term financing to fund operations.

The city now has about $8 million in reserves, but used $3 million of it this year to cover Sandy recovery expenses while awaiting reimbursements.

Analysts said the city’s declining available funds show a history of budget imbalances, but it still has a positive balance compared with the negative reserves the city had when it was facing near-junk-bond status.

“We’re not anywhere near where we were in 2011-12 and saw negative cash positions. We’re not there yet,” Weber said.

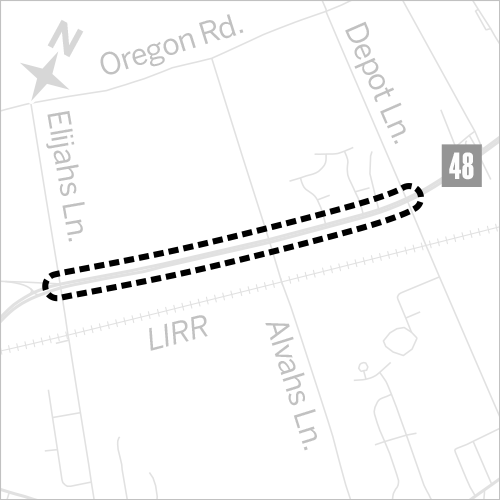

Long Beach was inundated from the Atlantic Ocean to the back bay, flooding the entire city and destroying the iconic boardwalk.

The city was also flooded with cash from federal and state emergency disaster recovery funds.

As the city sought to rebuild “stronger, smarter, safer,” portions of some projects were not reimbursed with storm money, adding to the debt and budget shortfall.

The city also used the government reimbursements to pay salaries to office clerks and workers completing the rebuilding projects, Eramo said.

Using disaster funds to cover indirect costs such as permanent salaries of workers and office staff so cities don’t have to slash workforce while rebuilding is common, municipal finance experts said.

“Money from the federal government is easy money, but it’s hard to balance a budget with counting it as reoccurring revenues,” Fabian said.

The state comptroller upgraded the city’s fiscal stress rating to “moderate” in 2016, but Schnirman cautioned that a “short-term infusion” of Sandy dollars was not sustainable without a long-term recovery plan.

More than five years after the storm, the city is still waiting for about $7.5 million in state and federal reimbursements. Long Beach officials recently issued a $4 million tax anticipation bond while awaiting reimbursement for boardwalk rebuilding work.

Moody’s stated in its May 4 report that “any expenses that are not reimbursed will result in additional long-term debt.”

State officials and credit agencies monitoring Long Beach’s finances said the warning signs of a budget crisis were flagged for city officials but in some cases not addressed.

Schnirman issued a transition memo on Dec. 31 to city leaders that included money-saving recommendations on department changes and cuts, such as restructuring public works, reducing part-time workers, privatizing day care and summer camps, and adding parking meters to increase revenue.

Schnirman said at the time he told the council that hard choices would have to be made, including proposals such as cutting the city’s 17-member paid fire department. The City Council rejected layoffs, and settled on fee inceases and tax hikes averaging 2.3 percent since Sandy.

“These are not the same problems we faced in 2011. The city is in a different place now and has come a long way,” Schnirman said in an interview last week. “The city funded a recovery after Sandy, taking the burden off taxpayers.”

DiNapoli’s office in April listed the city as being in significant fiscal stress, signaling a “deteriorating financial condition” and warning of significant tax increases.

City officials responded to the rating by noting the fiscal stress was due to Sandy funds that had not yet been reimbursed.

DiNapoli’s office determined this year’s proposed budget had balanced revenue projections of $41.5 million, “but does not include measures to improve financial condition.”

The comptroller’s office has cautioned the city for years to reduce overtime, which has averaged around $3 million for the past five years — about $300,000 more than budgeted last year.

The past two budgets have counted on $900,000 in sewer runoff fees from a contested $336 million 522-unit oceanfront apartment development starting construction on the Superblock parcel, a prime piece of undeveloped land along the boardwalk. The project stalled and the fees were not paid. The revenue stream was scratched from this year’s proposed budget as the future of the project remains uncertain.

Acting City Manager Michael Tangney said the lost funds contributed to a $1 million shortfall in revenue in last year’s budget, combined with another $200,000 shortage in the city’s recreation fees.

The state comptroller’s April review found that personal service contracts and employee benefits make up 75 percent of the city’s annual $41.5 million revenue and almost 12 percent in debt interest from bonds.

“With these costs accounting for 87 percent of revenue, there is limited ability to finance operations and maintain infrastructure,” comptroller officials said.

Long Beach issued deficit reduction bonds in 2014. The city has since reduced its operating funds by $3 million — to $8.4 million, according to Moody’s.

“The city had a financial position that was relatively healthy, but since that point, we’ve seen reserves decline and significantly,” Moody’s Weber said. “Basically, the liquidity over the last few months has dropped far more significantly than we anticipated.”

Moody’s said in its May 4 report that the city’s bond rating could be downgraded if its 2018 financial results are worse than anticipated, if available cash deteriorates, and if reserves are relied on to balance the budget.

Long Beach has counted on balancing its budget using borrowing and issuing bonds to pay for operating expenses such as separation payments, Moody’s and state officials said.

The state comptroller’s office said budgeting for “termination salaries is somewhat misleading as they also include cash payments for accrued leave to employees that remain employed by the city.”

Long Beach officials said union and nonunion employees for decades have been allowed to be paid for accrued time to reduce larger payouts to retirees later.

The payouts have averaged $2.6 million over the past three years, according to the comptroller’s review. A Moody’s report said the city will need to use an additional $1.75 million in previously approved bonds to cover separation payments and Sandy expenses this fiscal year through June.

Comptroller officials warned that if the city could not fund operations, the city could face a $2.1 million shortfall heading into the next fiscal year.

“The city’s continued practice of borrowing to fund these operating costs is not fiscally prudent,” comptroller officials said. “The practice will saddle future taxpayers.”

City Council members Anthony Eramo and Chumi Diamond have crafted a six-point plan to address the city’s finances.

1. Work with the comptroller’s audit team to improve budgeting practices.

2. Budget real dollars from city revenues for future separation payments and earned-leave obligations.

3. Require all separation or earned leave obligations more than $5,000 to have City Council approval.

4. Audit 2018 separation payments and pass legislation that limits the city manager’s authority for future payments.

5. Take remedial action if separation payments were miscalculated.

6. Ban anyone convicted of a crime against the city from receiving any separation pay or accrued time.

he luxury and grandeur of the Gold Coast befit a royal — say, Meghan Markle. The American-born actress — this year’s most-buzzed-about bride-to-be — will exchange vows with Prince Harry on May 19 at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle.

he luxury and grandeur of the Gold Coast befit a royal — say, Meghan Markle. The American-born actress — this year’s most-buzzed-about bride-to-be — will exchange vows with Prince Harry on May 19 at St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle.