By Bob Glauber

The erratic behavior started in 1998, long after John Mackey’s career as one of the NFL’s greatest tight ends had ended.

Finally, in December 2001, his wife, Sylvia Mackey, got some answers.

John Mackey, a star at Hempstead High School who played at Syracuse University and then enjoyed a Hall of Fame career with the Baltimore Colts, was diagnosed with dementia. Complications from the disease took his life on July 6, 2011, at age 69.

In December 2012, the Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy revealed that Mackey had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in people — most notably athletes — with a history of repetitive brain trauma.

His diagnosis and death were reminders about the dangers of concussions and how they impact players after they leave the game. Former players suffer in varying degrees from the head injuries they sustained, and while the NFL has instituted safety measures to reduce the incidence of concussions, it is too late for the former players who now deal with the aftereffects.

According to the NFL, the number of concussions suffered in preseason and regular-season practices and games during the 2013 season dropped to 228, a 13 percent decrease from the 2012 season, when there were 261 concussions. The NFL said there were 252 concussions during the 2011 season. The numbers, however, do not include concussions suffered in playoff games.

Still, there are no guarantees that today’s players and those who will eventually play in the NFL will avoid concussion-related problems.

“I’ve seen so many at the Hall of Fame . . . and [the wives] started asking me questions about what did I see in John at first,” Sylvia Mackey said. “I could tell by looking at their faces that they were going through the same thing.”

She eventually grew so alarmed that she wrote a letter to NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue in 2006. “I said, ‘Paul, I feel that this [dementia and concussions] are not a coincidence,’ ” she said. ” ‘Whether it was caused by football or not, the league needs to step up and take care of these players.'”

Within a year, the NFL, which lacked specific benefits for former players dealing with brain-related illnesses, launched the “88 Plan,” named after Mackey’s uniform number with the Colts. The plan provides $88,000 per year for nursing home care and as much as $50,000 a year for adult day care for each former player in need. In 2010, the league included former players suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease, to the “88 Plan.”

The aftereffects of concussions have taken a heavy toll on former players. Some are deceased, due in part to problems associated with repeated head trauma.

Junior Seau, the former San Diego Chargers, Miami Dolphins and New England Patriots linebacker, died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on May 2, 2012. It was later determined by the National Institutes of Health that Seau’s brain showed abnormalities associated with CTE.

Dave Duerson, the former Chicago Bears and Giants safety, died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the chest in 2011. In a suicide note, Duerson asked his family to donate his brain to the Boston University School of Medicine, which has a department devoted specifically to studying former players’ brains. According to the Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, Duerson was suffering from a “moderately advanced case” of CTE. Boston University also revealed that the CTE in Duerson’s brain was severe in areas that influence impulse control, inhibition, emotion and memory.

Other deceased former players diagnosed with CTE include Pittsburgh Steelers center Mike Webster, Philadelphia Eagles safety Andre Waters, Tampa Bay Buccaneers offensive lineman Tom McHale and Steelers offensive linemen Justin Strzelczyk and Terry Long.

More than 4,500 former players sued the NFL, charging that the league knew of and hid evidence of the dangers of concussions. The case was settled in August 2013 for $765 million. But U.S. District Court Judge Anita S. Brody rejected that agreement in January 2014, because she said there wasn’t enough money in the settlement to satisfy all future claims. The two sides agreed last July on a revised financial package that would eliminate the cap on damages. Brody has not yet ruled on the adjusted terms so no payments have been made to former players.

The settlement, however, did not represent an admission of liability by the NFL, nor did the league admit that the players’ injuries were caused by football. Among the litigants were Dallas Cowboys Hall of Fame running back Tony Dorsett, Buffalo Bills Hall of Fame offensive lineman Joe DeLamielleure and Giants two-time Super Bowl champion defensive end Leonard Marshall. All were diagnosed with likely CTE and/or symptoms associated with dementia that are consistent with CTE.

But not all players experience concussion-related problems after they leave the NFL. Boomer Esiason was playing quarterback for the Jets in 1995 when he was knocked out in a game after a hit by Buffalo Bills Hall of Fame defensive end Bruce Smith.

“I didn’t realize that it was going to be a five-week time period before I got back on the field,” said Esiason, who lives in Manhasset and played high school football at East Islip. “The hit I’ve seen a thousand times since then. I knew it was significant. I knew it was going to be intense. And I realize now when I went back on it, the right thing was for me not to play for five weeks because it was a scary hit.”

Today, Esiason, 53, who also played for the Cincinnati Bengals and Arizona Cardinals, is an NFL analyst for CBS and weekday talk-show host on WFAN. He said his health is generally good.

Harry Carson, a Hall of Fame linebacker with the Giants from 1976 to 1988, was one of the first NFL players to take a proactive approach toward the concussion issue. In 1990, he was diagnosed with post-concussion syndrome by a doctor referred to him by Giants trainer Ronnie Barnes. Post-concussion syndrome is a condition associated with a head injury that can last for weeks or months. Carson has since become an advocate for more awareness of the dangers of head trauma.

Carson, now 61, looks back and says he would not have played football. But a Newsday survey of 763 former pro football players found that 89 percent (680 respondents) would play in the NFL again if given the chance. The survey also found that 57 percent (434) were diagnosed with a concussion during their playing careers. When asked what ailments they now suffer from that they believe are related to their NFL playing days, 49 percent (371) said the head.

Carson said he did not know about the potential for brain damage while he was playing.

People ask me if I had to do it all over again, and I say, ‘Knowing what I know now from a neurological standpoint, I would not play,’ ” Carson said. “Nobody told me about the whole brain injury issue.”

Carson, who was not a part of the concussion litigation against the NFL, said he is saddened by the plight of former players dealing with the aftereffects of head injuries, particularly those who have taken their own lives. He believes greater awareness can help prevent such tragedies and allow players to lead more normal lives once their pro careers end.

“I noticed the problems a long time ago, when most guys didn’t notice it,” he said. “Quite frankly, my feeling was that if it’s happened to me, it’s probably happening to a lot of other guys. That’s why I talk about it, to let guys know that there is something going on and that there’s something you can do about it.

“I feel like if the message got out that it was something that was manageable, then you wouldn’t have the Junior Seaus and Dave Duersons and any other guys killing themselves, because it’s manageable . . . Most guys who don’t have a diagnosis, they’ll think they’re off their rocker and they’ll resort to doing something their families regret.”

Marshall, 53, was recently told that he has symptoms commonly associated with CTE. He underwent a battery of tests at UCLA last year after experiencing a variety of symptoms, including memory loss, headaches and mood swings.

“I’m glad I know what’s going on now,” Marshall said. “I think it’s important we come forward with our situation. It really tests your ability to be patient with people and you have to deal with it on a daily basis. You have to learn to temper your behavior and deal with some of the issues associated with the disease.”

Chris Nowinski never played in the NFL, but he is deeply invested in the health and well-being of former players, particularly those who are dealing with concussion-related problems.

Nowinski was an All-Ivy defensive tackle for Harvard, but became a professional wrestler in 2002. He suffered a serious concussion in 2003 and developed post-concussion syndrome, which forced him to retire. Nowinski’s own injury taught him about the lack of awareness for concussions and brain trauma. He wrote the book “Head Games: Football’s Concussion Crisis,” which was published in 2006. He has worked with several retired NFL players in an effort to better understand the aftereffects of concussions. Nowinski co-founded the Sports Legacy Institute in 2007 and then partnered with the Boston University Medical Center a year later to research concussions, in part by studying the brains of deceased players.

According to Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, 76 of the 79 brains of deceased NFL players studied at the Department of Veterans Affairs’ brain repository in Bedford, Massachusetts, have showed some form of CTE.

“With the state of football, I think it’s clear that CTE is not an isolated problem,” said Nowinski, the co-director of Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. “We’re trying to unlock more information on what the disease is so that we can find ways to prevent it and treat it.”

The NFL is also spending millions on research involving brain injuries, partnering with the National Institutes of Health and providing funding to the Boston University study center.

“We obviously are very interested in the [BU] center’s research on the long-term effects of head trauma in athletes,” NFL commissioner Roger Goodell said in announcing a $1 million grant. “It is our hope that this research will lead to a better understanding of these effects and also to developing ways to help detect, prevent and treat these injuries.”

NFL concussion data: Practice vs. Game(includes preseason and regular-season games)

NFL concussion data: Preseason vs. Regular Season

The NFL has since attempted to make its game safer through rules changes and increased awareness about the dangers of concussions. In 2013, the NFL’s head, neck and spine committee introduced new protocols for diagnosing and managing concussions, which included detailed steps for a player to return to the field after suffering a concussion. The NFL also put more emphasis on protecting players from helmet-first hits to the head and neck.

But Nowinski isn’t sure enough is being done.

“It’s going to be hard to solve the problem for the pros playing today in terms of preventing CTE, particularly because they’ve all come up in a football environment that didn’t pay attention to concussions,” Nowinski said. “I think there will be inherent conflicts forever, in that most guys from the team don’t have secure jobs and are not going to be forthcoming with concussions because they’re so common.”

Marshall wants people to know that the damage is real for former players dealing with concussion-related issues.

“We’re private people now and no longer professional athletes playing the game,” he said. “I think there’s a lot of fortitude that’s being exhibited in bringing our situation to the forefront and letting America have a chance to see what’s going on.”

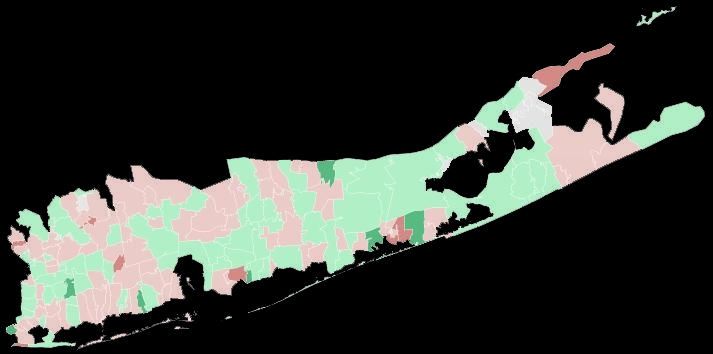

Holtsville Hal

56.3% accurate

Holtsville Hal

56.3% accurate

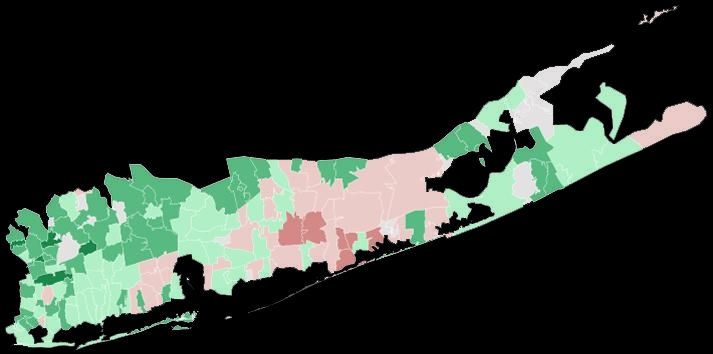

Malverne Mel

52.6% accurate

Malverne Mel

52.6% accurate

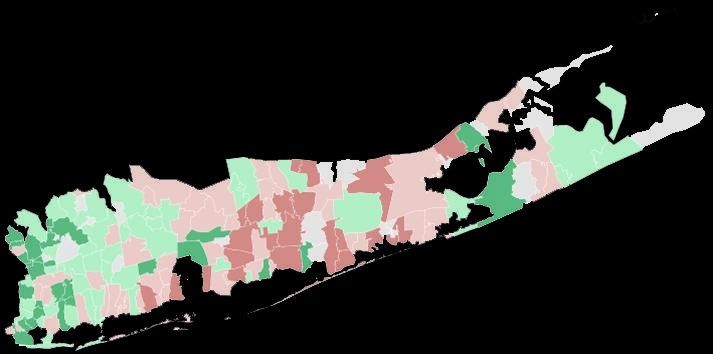

Staten Island Chuck

57.9% accurate

Staten Island Chuck

57.9% accurate

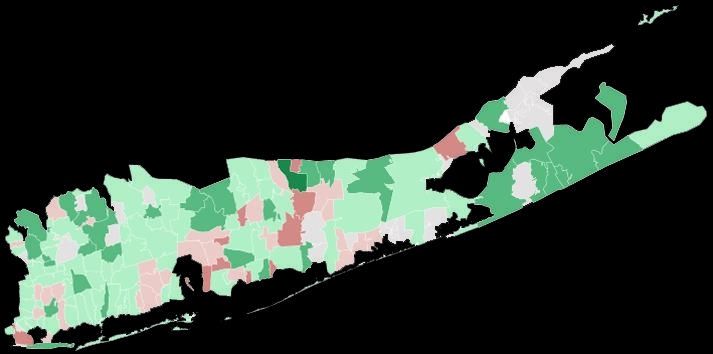

Punxsutawney Phil

47.4% accurate

Punxsutawney Phil

47.4% accurate