Homecoming football games have provided all kinds of excitement on Long Island this year. But whether the home team is winning or losing, high school cheerleading and kickline teams make sure everyone has a good time. Click on the photos below to watch video snippets of team performances that Newsday.com community journalists Tara Conry and Amy Onorato and contributors Jennifer A. Uihlein, John Friia and Ann Luk shot on their cellphones while covering homecoming celebrations. Homecoming is just the beginning for many of these teams as competition season gets underway. Bookmark this page, as we’ll be adding more videos when the trophies are up for grabs. Do you have photos, video footage or an interesting story to share about LI’s cheer and kickline teams? Email submissions to Josh Stewart at josh.stewart@newsday.com.

Month: October 2014

Superstorm Sandy: Two years later

Documentary

Until everyone comes home

For the past two years, families whose homes were severely damaged let Newsday document how the storm impacted them. For the storm's second anniversary, they discussed being displaced and rebuilding.

Newsday / Jessica Rotkiewicz and Newsday / Chris Ware

Latest stories

See complete coverage of LI's recovery after Sandy

NY Rising

New York Rising starts demolishing Sandy-damaged homes

Data

Information on the first 25 projects funded by NY Rising

Infrastructure

$96M mission to protect LI from major storms

Reimbursements

$21.4M in refunds for Sandy-affected owners

LIRR

LIRR still a long way from storm readiness

Rebuilding

'Not over'

Thousands of LIers are still struggling to survive superstorm Sandy

Rebuilding

Sandy's victims

10 Long Islanders share their stories

Then & Now

LI & NYC after Sandy

See dramatic images from the aftermath of the storm six months, one year and two years later

PSEG

LI's electric system improved, but untested

Looking ahead

After Sandy: Are we ready for the next big storm?

Rebuilding

Red Cross announces $2M in grants to survivors

Rebuilding

Finding a new cause

During Sandy, volunteers emerged as local heroes and their missions continue two years later

Summer after Sandy

Heading into Long Island’s first summer after superstorm Sandy, many Long Islanders were still dealing with the storm’s destruction on a daily basis, and worrying about how they would fare during the island’s busiest season. From homes to businesses, beaches and roads, this series shows some of the dramatic images from the aftermath of the storm and the same locations six months later. Photos on the left show the damage after the storm; photos on the right show those areas now. Move the slider — the vertical divider between each set of photos — left or right for the full photo. Mobile users can tap anywhere on a photo to move the slider.

Use the navigation tools at the top of the page to see then and now photos from one and two years after Sandy.

South Bay flooded Oak Island homes during superstorm Sandy. Those not completely destroyed are in the midst of repairs.

Only about half of the residents in the West End section of Long Beach have returned to their homes since Sandy wiped out the area’s one-level bungalows and the first floors of many two- and three-story homes.

Of all of Long Island’s state parks, Jones Beach required the most repairs, with park employees, state agencies and 17 contractors beginning the work within days of the storm.

When superstorm Sandy pummeled the Nautical Mile in Freeport, Tropix bar and restaurant was devastated by the storm surge, high winds and a raging fire.

Many of the East Massapequa homes that sit directly on the Great South Bay are vacant. Storm surges during superstorm Sandy ripped apart walls, shattered windows and washed away parts of the houses.

A sense of rejuvenation is washing over visitors after the boardwalk was recently repaired and debris has been cleared. The beach, too, seems to be making a natural comeback.

When the more than 4 feet of water that flooded Shore Road in Lindenhurst receded, the damage left behind was both material and emotional.

The oceanfront beaches in Montauk lost nearly 75 yards of sand to erosion after superstorm Sandy, leaving shores nearly 2 feet lower than they were before and oceanfront homes and hotels with their foundations exposed.

Ocean Parkway suffered such severe Sandy damage that New York State awarded a $33.2-million contract to three New York-based companies to repair it just a month-and-a-half after the storm hit.

Long Beach was one of the areas hit hardest by superstorm Sandy, and the most iconic part of the city to fall prey was the boardwalk.

More than 4 feet of water flooded the Nikon at Jones Beach Theater, damaging its VIP boardwalk, box office, electrical system, orchestra seating and concession supplies.

Water from Moriches Bay flooded the southernmost part of Ocean Avenue in Center Moriches, bringing 4 feet of water into the streets and many of the homes.

Fire Island’s recovery from Sandy has been equal parts resolve and rumination — how to rebuild while coming to terms with man’s limits vs. Mother Nature. But while the discussion goes on, locals are preparing for summer as usual.

The Village of Mastic Beach saw widespread flooding, downed trees, outages and homes damaged. While much has been cleared, some residents are still struggling to make repairs, while others have left altogether.

Many of the ground-level homes in Westhampton Beach were flooded by storm surges from Moriches Bay. As summer nears, signs of hope and normality are returning.

Most Freeport residents are back in their homes, but many are still repairing the damage from a 9-foot storm surge that crested over nearby Woodcleft Canal.

Residents living on South Wellwood Avenue in Lindenhurst are still trying to restore their homes, which took in roughly 4 feet of water laced with silt, fuel and debris from the Great South Bay.

Water from Moriches Bay swept over the small spit of land between Ocean Avenue in Center Moriches and Inletview Place, breaking down boat docks and house walls, and flushing out homes.

One year after Sandy

This interactive project highlights some dramatic images from the aftermath of superstorm Sandy and the recovery efforts one year later. Photos on the left show the damage after the storm; photos on the right show those areas now. Move the slider — the vertical divider between each set of photos — left or right for the full photo.

Use the navigation tools at the top of the page to see then and now photos from two years and six months after Sandy.

The popular Fiore Bros. Fish Market which had been in business since 1920 on Freeport’s Nautical Mile burnt to the ground after superstorm Sandy. The restaurants and bars on the mile-long stretch that runs along Woodcleft Canal were ravaged by the storm. Most businesses reopened by Memorial Day, but some like Fiore Bros. are still recovering.

Cars along Long Beach’s Michigan Avenue were submerged by water and sand after superstorm Sandy. Long Beach was among the hardest hit communities on Long Island and continues its efforts to rebuild. FEMA provided the city, its schools and the Long Beach Medical Center more than $39 million in aid.

Homes along Bayview Avenue West in Lindenhurst were pummeled by superstorm Sandy. Another of the harder hit areas on Long Island, the village and its schools received more than $7 million in FEMA aid to assist in the recovery.

The Statue of Blessed Mother once overlooked the charred remains of the smoldering homes on Gotham Walk in Breezy Point. Superstorm Sandy devastated the area damaging or destroying more than 100 homes.

Ransom Beach in Bayville was completely submerged by waves as superstorm Sandy walloped the village tucked between the Sound and the waters of Oyster Bay. The storm surge reached 11.06 feet in Bayville.

A home along West 5th Street in Ronkonkoma damaged by a fallen tree after superstorm Sandy ripped through Long Island had to be completely rebuilt. Sandy damaged or destroyed more than 95,000 structures on Long Island.

Joe and John Toto’s Restaurant and Bar was among the Staten Island businesses that suffered damage after superstorm Sandy. New York City officials have acknowledged that many residents are still waiting for financial aid to rebuild their damaged homes but said the city’s infrastructure has been strengthened.

Superstorm Sandy lifted boats from the water onto the docks along Barnum Island in Island Park. The village received $872,029 in FEMA aid and is seeking $45 million in federal hazard mitigation funds to make drainage improvements and infrastructure repairs.

Joseph Leader, Metropolitan Transportation Authority vice president and chief maintenance officer, tours the inside of the South Ferry train station in Manhattan. The MTA was forced to shut down train, subway and bus service after superstorm Sandy.

Long Beach was one of the areas hit hardest by superstorm Sandy, and the most iconic part of the city to fall prey was the boardwalk. Officials said the city’s rebuilt boardwalk was “substantially complete” in October with a pricetag of $44.2 million.

The Sea Breeze Cafe in Babylon Village was completely submerged by superstorm Sandy. Long Islanders received more than $87 million in Small Business Administration business loans for damage suffered by the storm.

Superstorm Sandy breached the seawalls of the Battery in lower Manhattan, swamped part of the subway system and poured into the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel (also known as the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel).

Some homes along Clocks Boulevard in Massapequa destroyed by superstorm Sandy still have not been rebuilt. Long Islanders received more than $725 million in Small Business Administration home loans.

Superstorm Sandy damaged or destroyed more than 100 homes in Breezy Point. Sandy inflicted about $33 billion in damage to the state and plunged more than 1 million households into darkness for more than two weeks.

Superstorm Sandy scattered boats and debris throughout Empire Boulevard in Island Park. The village is seeking $45 million in federal hazard mitigation funds to make village-wide drainage improvements and infrastructure repairs.

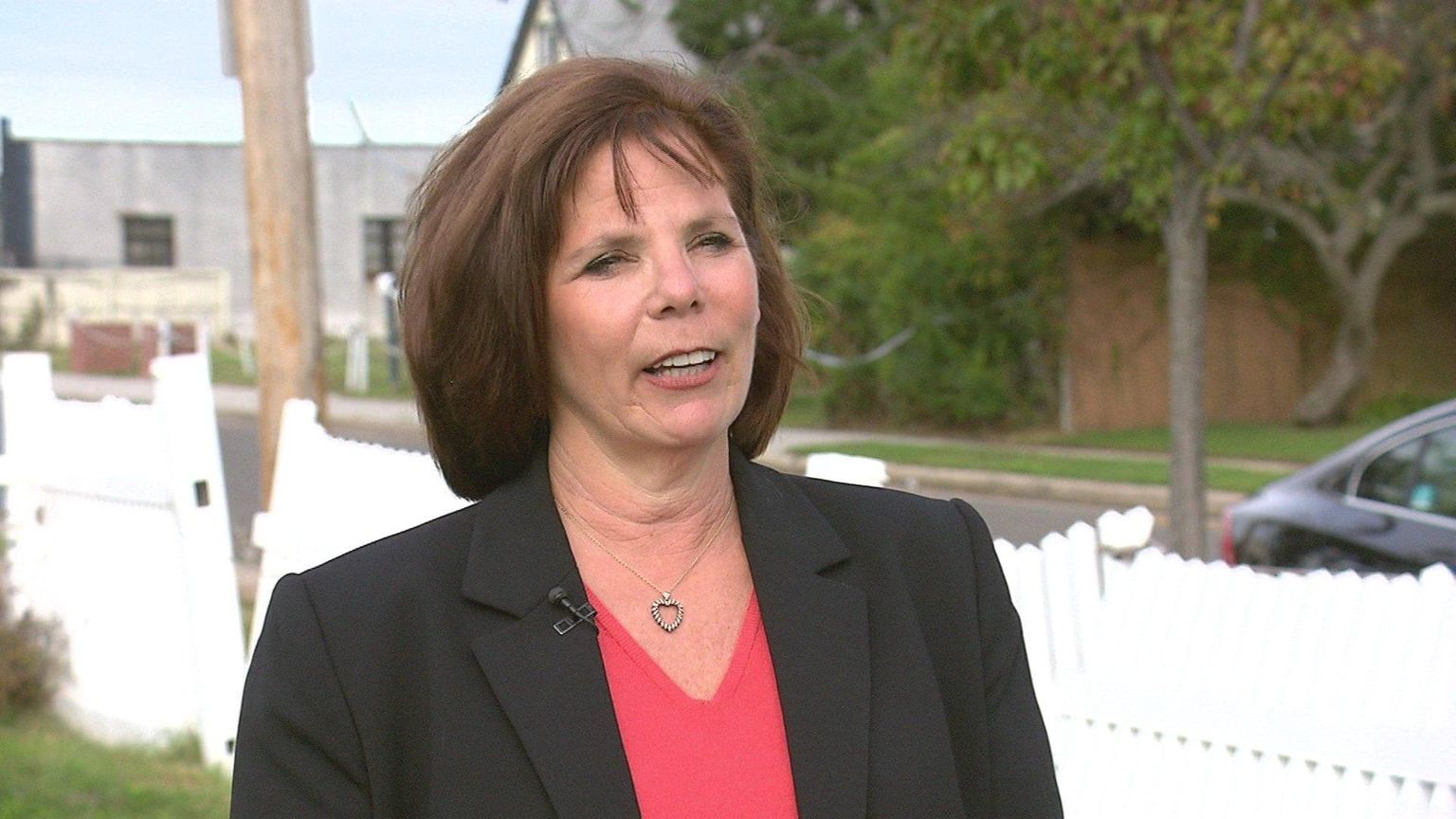

Croci maintains lead over Esposito in Newsday/News 12/Siena poll

Republican Tom Croci continues to hold a substantial lead over Democrat Adrienne Esposito in New York’s 3rd Senate District, according to a Newsday/News12/Siena College poll.

Croci, the Islip town supervisor, leads Esposito, a longtime environmental activist, 59 percent to 34 percent among likely voters in the district, which covers parts of Brookhaven and Islip. The survey of 425 likely voters was taken Oct. 20-23 — a week after Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo announced his support for Esposito. The poll has a margin of error of plus or minus 4.7 percentage points.

The numbers in the race have hardly budged from a benchmark poll one month earlier. That poll showed Croci ahead 56-29.

“It does seem noteworthy that this race hasn’t closed,” said Don Levy, director of the Siena College poll. “It doesn’t appear she’s succeeded in gaining traction.”

To see raw data, click here.

Who would you vote for today between Adrienne Esposito and Tom Croci?

In contrast, there was noticeable movement among district residents’ views on the gubernatorial race. The October survey found Cuomo, a Democrat, leading Republican challenger Rob Astorino 44 percent to 41 percent — down from 13-point difference just a month earlier.

Levy noted that Cuomo “lost traction in the district, even among Democrats,” since the September poll, a trend that may or may not affect the Senate race. In September, 78 percent of Democrats said they favored Cuomo, 10 percent Astorino and 4 percent Green Party candidate Howie Hawkins. In October, that shifted to Cuomo, 67 percent, Astorino, 15 and Hawkins, 13.

Esposito and Croci are vying to replace Sen. Lee Zeldin (R-Shirley), who is leaving the State Senate to run for Congress against Rep. Tim Bishop (D-Southampton).

On the bright side for Esposito, her name recognition has almost doubled since September. On the down side, her negative ratings grew faster than her positive. About 28 percent of district residents surveyed now say they view her favorably while 38 percent said unfavorable.

How likely would you say you are to vote for Adrienne Esposito or Tom Croci?

“She is better known, but not in a way that enhances her electability,” Levy said.

Meanwhile, Croci was viewed favorably by 59 percent of respondents and unfavorably by 24 percent. He even gained a split among registered Democrats, 39-39.

Croci also fared much better than Esposito at gaining independent support. Among independent and third-party voters, he leads 58-34.

“He is really cleaning up with independents,” Levy said of Croci. “She needed to flip that around and she hasn’t.”

Regardless of your support, which candidate do you think has waged the more negative campaign?

Croci enjoys strong core support from his party’s base. Eighty-eight percent of Republicans said they back Croci, while 61 percent of Democrats favor Esposito.

The district is 35 percent Democratic and 31 percent Republican. But Republicans historically have voted in larger numbers than Democrats in the district, according to Siena.

Despite the big lead, Croci spokeswoman Christine Geed said only: “This election is too important to take anything for granted. The results that count are next week on Election Day. Until 9 p.m. on November 4th we are going to continue running an aggressive campaign about Tom Croci being the only candidate who can create jobs and improve the quality of life for the families of Long Island.”

Esposito’s campaign manager highlighted her increased visibility and tried to link Croci to a toxic dumping scandal in Islip that occurred while he was town supervisor but when he was in Afghanistan on naval duty.

“Tom Croci has spent over half a million dollars lying about Adrienne’s record and the truth is she has gone up in the polls,” said Esposito spokesman Michael Fricchione. “Croci is relying on shady New York City special interest money and money from illegal toxic dumpers, which has flooded the airwaves with his lies. At the end of the day, Adrienne Esposito is the only candidate in this race who is out there fighting for hard-working, middle- class families . . . “

As Election Day draws near, survey respondents contacted by Newsday indicated they were voting along party lines.

Kevin Keeley, a school teacher who lives in Islip, said he supports Esposito because he wants Democrats to control the state Senate.

“They typically lean more the direction I lean toward,” Keeley said. Noting his family received helpful social assistance when he was growing up, he added: “They lean more toward social programs. I like the idea of supporting them.”

Similarly, Leigh Ross, a flight attendant who lives in Ronkonkoma, said she supports Croci because he’s Republican.

“I’m very conservative, so I lean more toward the conservative,” she said. “I feel like he’s a better candidate.”

Questions on Rice’s early prosecution cases

“Disgruntled defendants sue the DA’s office all the time. Having only one case against me puts me in the baseball Hall of Fame as far as I’m concerned.” –Kathleen Rice, nine years agoRecords and depositions reveal that Rice and detectives locked in on Butts and discounted information pointing to another man who matched the shooter’s profile. Butts’ suit alleged that Rice and detectives coerced witnesses into testifying against him, and one of the witnesses claimed under oath that he was ignored when he protested that the wrong man was being targeted. Rice and the detectives denied the witnesses’ allegations during the civil suit. Experts who reviewed details of several of Rice’s cases at Newsday’s request differed on their assessments of her conduct as a prosecutor. Eugene O’Donnell, a John Jay College of Criminal Justice professor who was once colleagues with Rice in the Brooklyn district attorney’s office but did not work closely with her, said that Rice’s prosecutorial issues reflected “the typical job of the DA.” “There are glaring gaps in the cases, the victims have issues, the witnesses have issues,” O’Donnell said. “It’s baggage city. But you still have to bring the bad guys to justice.” Peter Davis, a professor at Long Island’s Touro Law Center, where Rice was once his student, said the records show she avoided consequences despite failing to disclose favorable information to the defense, which is known as the Brady requirement due to the landmark Supreme Court case Brady v. Maryland. “It seems one pattern is the pattern of Rice suppressing Brady material,” Davis said. “And the second pattern is this pattern of judges not holding Rice accountable.” Pace Law School Professor Bennett L. Gershman, a former Manhattan assistant district attorney and an expert on prosecutorial conduct, said that Rice’s errors stood out. “There are many, many prosecutors out there who have been prosecutors for this long who aren’t saddled with these kinds of problems,” Gershman said. Troubled cases The failed Butts prosecution bears many similarities to the cases currently under review in Brooklyn. There was an absence of physical evidence, an eyewitness who was an admitted crack user, accusations of coercion by authorities, and the involvement of now-retired NYPD homicide Det. Louis Scarcella, who has been the focus the Brooklyn district attorney’s false-conviction probe. Seventy convictions Scarcella helped secure are among the cases under review. During a September court hearing concerning a convicted murderer who claims Scarcella set him up, the former detective noted that it was the prosecutors who oversaw every arrest he made. “During my tenure as a detective in Brooklyn, which was about 19 years, we did not make the arrest,” Scarcella said. “We had to bring it to the Brooklyn district attorney’s office and they authorized the arrest. We did not.” Scarcella declined to comment for this story. He and his longtime partner, Stephen Chmil, were the first detectives at the scene of a double homicide in a Brooklyn bodega on Dec. 30, 1997. Scarcella and Chmil were integral to the case, interviewing witnesses, arranging photo lineups and ultimately arresting Butts, police records show. When Rice first arrived at the bodega, the store’s owner and a teenage employee were still lying behind the counter and in an aisle where they had been shot. “You are there to make sure that things are done correctly,” Rice said of her role during a 2005 deposition. The investigation found its key witness two days later when police arrested Martin Mitchell for allegedly ringing in 1998 by firing a pistol out of an apartment window. Cops found guns, ammunition, a silencer, a police-issued bulletproof vest and scanner, handcuffs and a gas mask in the apartment. Hoping to trade information for favorable treatment, an “intoxicated” Mitchell, according to a detective’s later deposition, tapped his hands on an interrogation room table and said: “I have something big.” Mitchell said, according to a statement taped by Rice, that three men had been involved in the bodega shooting, including a man known as “Black” from Tapscott Street. He said he witnessed the group plan to rob the bodega and was across the street from the Brownsville shop when the murders occurred. Mitchell denied being in on the crime but acknowledged accepting money and crack to keep quiet.

“There are glaring gaps in the cases, the victims have issues, the witnesses have issues. It’s baggage city. But you still have to bring the bad guys to justice.” — Eugene O’Donnell, a John Jay College of Criminal Justice professor

In later civil depositions, Rice and two detectives suggested that Mitchell’s account struck them as at least partially not credible. Detectives said they suspected that Mitchell was involved in the murders. “We were looking at it that he could have been and probably was part of it,” Det. Robert Schulman said in his deposition. “Of course, the way he was saying it, I mean it sounds like the guy was a lookout,” Det. Stephen Hunter said. In her own deposition, Rice said that Mitchell’s statements were “never shown to be untrue” and that relying on him as a witness had to “be seen in the prism of prosecuting cases in Brooklyn.” “My experience in Brooklyn in a neighborhood like this, you had to deal with witnesses not as credible as you like,” Rice said. Two days later, Rice recorded the interview of another alleged eyewitness to the shooting, a 15-year-old girl who said she saw a masked man nicknamed “Black” fight with the bodega owner before the shots rang out. The girl said she, her boyfriend and her dog followed the three shooters, who discussed the murders within earshot and handled weapons and a wad of cash. Butts’ attorney in both his criminal defense and later civil suit, Bruce A. Barket, said in a recent interview that the girl’s story suggested “she could see through a wall and a mask to identify a person she had never met before.” It was Scarcella who then steered the investigation toward Butts, another detective recalled during a sworn deposition, following a canvass of bodega owners, one of whom said he knew of a neighborhood man nicknamed “Black” who was in a group that robbed bodegas. Police then identified that man as Butts. In the civil suit, Barket alleged that the 15-year-old girl was threatened with her adult boyfriend’s prosecution for statutory rape if she didn’t implicate Butts. The girl was not deposed during the civil suit. Rice and the detectives denied that they coerced her statement. Mitchell would make similar allegations. He later claimed that after he told detectives that Butts was not the right man, he was told to implicate him anyway or face gun charges. “They just kept pushing the issue,” Mitchell said in a 2004 jailhouse deposition while serving an unrelated prison stint. “Tell me if I didn’t agree, they was gonna nail me with the case.” Mitchell included Rice among those who coerced him into implicating Butts. Mitchell recalled her as an aggressive prosecutor who intimidated him with “several threats” of prison time if he lied or didn’t cooperate. Rice and the detectives denied Mitchell’s allegations. A case crumbles A grand jury indicted Butts and charged him with multiple counts of first-degree murder. Though two other men were arrested, they were not charged. Less than two months later, a judge dismissed the charges against Butts on the grounds that the evidence presented to the grand jury was insufficient. However, Rice filed an appeal and the charges were ultimately reinstated. By the time Butts was tried in 2000, Rice had moved on to prosecute federal cases in Philadelphia. The case she helped put together in Brooklyn quickly fell apart. Transcripts of the trial have been sealed, but according to a New York Times account, Mitchell undermined his testimony by admitting that he was high on drugs and drunk within a day of the shooting. When asked what time the crime occurred, Mitchell reportedly replied, “I can’t remember people. How am I going to remember time?” Hynes acknowledged in a letter to The New York Times that flawed witness testimony doomed the case. “The jury acquitted Mr. Butts because two eyewitnesses contradicted their earlier statements to police and prosecutors when they testified at trial,” Hynes wrote. In pursuing Butts, the investigation cleared a known drug dealer nicknamed “Black” from Tapscott Street, records and depositions show. The murders have not been solved. O’Donnell, the John Jay professor and former Brooklyn prosecutor, said that focusing on a primary suspect, even if it means ignoring different leads, is normal. “Sounds like a typical investigation, but it also sounds like something you should be concerned with,” O’Donnell said. “Law enforcement investigators are not looking to create doubt. You don’t set out to say, ‘Let’s weaken our case.’ ” Pace Law Professor Gershman said the evidence against Butts was “very weak.” “It hinges on witness statements which the prosecutor admitted didn’t make sense and were strange,” Gershman said. “What the heck are you prosecuting this case for?” Rice maintained in her deposition that building a case isn’t as tidy as it’s portrayed in the movies. “The fact is, sometimes you have to deal with the evidence that you are given,” Rice said. “It’s not like going to central casting and say, ‘This person is a witness, get me the bloody gun.’ ” Butts accused New York City, the district attorney’s office and several individuals, including Rice, of violating his civil rights in a federal lawsuit filed in 2001. The suit was ultimately settled in 2007 with the city paying Butts $220,000. “Everything I lost I cannot get none of that back, nothing,” Butts said in his own deposition, adding that prosecutors persisted with the case against him despite realizing he was innocent. “Once they point the finger they have to stick with it.” State records show Butts has not been convicted of any crime since he was acquitted for the bodega murders. In a 2010 report by City & State, a media organization that covers New York government and politics, Rice said she was certain Butts was guilty. “From the very beginning, I knew we had the right guy. There was no question in my mind at all,” she said. “Sometimes that happens — sometimes guilty people get acquitted.” In her 2005 deposition, Rice said she “was convinced we had the right person” but whether she could prove it was “a different question.” However, she also said the witnesses’ credibility problems had influenced her to recommend that Hynes not pursue capital punishment. “God forbid there is a mistake, there is no going back from that. You have to be very careful in that process,” said Rice. “I knew it was a difficult case, as most of my cases were.” A driven prosecutor Hynes hired Rice in 1992 at a $30,000 assistant district attorney’s salary. Rice, who was 26 at the time, was a Touro Law Center graduate who had interned at the Manhattan Legal Aid Society and worked as a clerk at a law firm. She had also interned for Nassau County District Attorney Denis E. Dillon, whom she would oust in an election more than a decade later. “Growing up the seventh of ten children, I was strongly encouraged to keep the needs and feelings of others in mind,” Rice wrote in a cover letter for the Brooklyn prosecutor’s job. Personnel records show that in an office with hundreds of other assistant district attorneys, she rose from general criminal court duty to prosecuting sex crimes and, ultimately, homicides. Her new workplace was the deadliest borough in a city reeling from the crack epidemic and record murder rates. Rice prosecuted 295 felony charges through 1999, according to statistics Newsday obtained via a public records request. Rice’s acquittal rate at trial for those felony charges was just over 30 percent, slightly higher than the average of her Brooklyn peers during that era, which was 26.4 percent. (Nine of Rice’s cases ended in unclear dispositions, according to numbers provided by the Kings County district attorney’s office. If every one of the nine cases ended in a trial conviction, Rice’s acquittal number would improve to roughly 25 percent.) A more detailed breakdown of the office’s statistics, such as by individual prosecutor or by case type, was not available. Phillips, Rice’s spokesman, said using the statistics to compare Rice with her Brooklyn colleagues is not valid. “Kathleen was appointed a federal prosecutor by the US Attorney because she tried the toughest cases in the most elite bureau against the most violent New Yorkers in the city’s most violent era. And she won. Comparing her trial stats on these cases to those of prosecutors going after bad-check writers is not only naive but intentionally misleading,” Phillips wrote in an email. When asked to provide evidence in support of his statement, Phillips provided none. Court case files from convictions Rice secured during the era show she pushed for a sentence of 25 years to life for Jose Gutierrez, who engaged in a shootout that killed an innocent bystander, and branded him a “cowardly punk” who “personifies the senseless stupidity of random violence that plagues our city.” Gutierrez’s attorney in the shootout case, Joseph Ostrowsky, accused Rice of a “litany of prosecutorial misconduct and recklessness,” including withholding from the defense grand jury testimony from three witnesses in the case. One of those witnesses said on the stand that he saw Gutierrez immediately prior to the shooting, testimony for which the defense was not prepared. Both the trial judge and an appeals court agreed that Rice delayed disclosure of the testimony, according to court records. The higher court declined to overturn the conviction, ruling that Rice had been “properly sanctioned” by allowing the defense further cross-examination of three witnesses. Interest of justice Disposition statistics show that one of Rice’s cases in Brooklyn was dismissed in the interest of justice, a circumstance where the judge has determined that pursuing the prosecution would be unjust. No information about the case is publicly available. Under New York State law, cases ending in dismissal or acquittal are automatically sealed from public view. Like every prosecutor, Rice’s successes — the guilty pleas and verdicts — are preserved in court files, while the failures are mostly closed to public scrutiny.

“There are many, many prosecutors out there who have been prosecutors for this long who aren’t saddled with these kinds of problems.” — Pace Law professor Bennett L. GershmanSex-abuse case Other allegations against Rice appear in an appellate decision involving NYC Emergency Medical Services lieutenant Carlos Ramos, who was convicted in 1995 of sexually abusing a 10-year-old. Ramos’ attorney accused prosecutors of misconduct, stating in the appeal that the prosecution, led by Rice, had withheld information concerning the dates of the alleged attacks. Given those dates, Ramos would have produced records showing he was at work at the time he was accused of abusing the boy, according to the appeal. Kings County Supreme Court Justice John M. Leventhal agreed that prosecutors’ actions “severely interfered with defendant’s ability to adequately prepare a defense and amounted to a denial of due process.” Citing “fundamental fairness and due process,” Leventhal ordered a new trial for Ramos. State records show the charges against Ramos were dismissed in 1997. Leventhal declined to address the accusation of prosecutorial misconduct, saying that “a further hearing would be necessary” to determine whether Rice or two fellow prosecutors had purposefully withheld evidence. Rice defended her handling of the Ramos case during the civil deposition in the Butts lawsuit. Rice said she could not have disclosed the date of alleged abuse because she didn’t learn it until the boy took the stand. In her experience with sex crimes, she said, there was a “difficulty to get children to remember specific dates,” so prosecutors would often charge that the abuse occurred in a general time period. Pace Law Professor Gershman said a prosecutor is responsible for getting such information and then ensuring that it has been turned over to the defense. “She’s preparing a case for trial that could result in a person spending much of the rest of his life in jail and yet she doesn’t ascertain the dates that the abuse occurred?” Gershman said. Less than three years after Rice left Brooklyn to work as a federal prosecutor in Philadelphia, she again faced accusations that she had withheld key information during a trial. A federal appeals court overturned Rice’s conviction of Alfonzo Coward, a felon sentenced to 68 months in prison after he was caught with a pistol in his car, because Rice had failed to reveal why Coward was pulled over in the first place. Rice’s colleagues defended her in court by saying she was “relatively inexperienced.” Two judges rejected that explanation. “We note that the prosecutor’s ‘inexperience’ did not prevent the government from selecting her to handle the obligations of a criminal trial and, indeed, she secured Coward’s conviction,” ruled U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. “Nothing suggests that the government in Coward’s case ‘overlooked’ a ‘detail’ by ‘inadvertence.’ This case is not one in which the misinterpretation can be justified because the law was ambiguous or changing.” In a separate ruling, Judge Stewart Dalzell of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania called the defense of Rice’s inexperience a “bald excuse” and a “very odd premise.” He added “the Government seems to suggest that the Fourth Amendment … does not (somehow) apply in Brooklyn as it does in federal district court in Philadelphia, and therefore Ms. Rice could not have been expected to be familiar with controlling law.” Two years after Rice’s handling of the case led to Coward’s early release from prison, Coward was arrested on charges of marrying and having sex with a 14-year-old girl. Those charges were later withdrawn. Rice downplayed the Coward error in an interview with Newsday in 2010. “It was one case in an 18-year career,” she said. Remaking DA’s office “It will be a real prosecutor’s office again,” Rice declared at her victory celebration in November 2005 after seizing the Nassau County district attorney’s office from 31-year incumbent Dillon. She remade the office in part by firing veteran prosecutors and replacing them with former Brooklyn colleagues groomed by Hynes. Rice hired Teresa Corrigan, a Kings County prosecutor for 16 years, to become a bureau chief. Corrigan, now a Nassau County Court judge, wrote in her resignation to Hynes that “it is with great pride that I will be taking everything I have gained from this office and applying it to the problems facing Nassau County.” Former Kings County Assistant District Attorneys Meg Reiss, Sheryl Anania and Mitchell Benson were also given top prosecutorial jobs in Rice’s administration. And Albert Teichman, who was Hynes’ longtime chief assistant district attorney, was hired for the same No. 2 spot in Nassau. Teichman, in his own resignation letter, called Hynes’ administration “one of the finest prosecution offices in the nation.” How Hynes operated his office has become an issue of intense interest due to the ongoing search for wrongful convictions. This past August, the city agreed to pay $10 million to settle a lawsuit filed by Jabbar Collins, whose homicide conviction was tossed amid allegations that prosecutors had threatened and coerced witnesses in his case. Two Eastern District of New York judges, Dora Irizarry and Frederick Block, called prosecutors’ actions in the Collins case “shameful” and “horrific” and criticized Hynes for turning a blind eye to misconduct. Thompson defeated Hynes in an election last year and took over the Brooklyn office in January. Hynes may face criminal charges after a New York City investigation found that he used law enforcement money for campaign expenses. Barket, who represented Butts and another man freed early from a prison sentence following allegations that a Brooklyn prosecutor withheld information during his murder trial, said that Rice’s tutelage under Hynes is especially meaningful when it comes to her handling of Brady material. “She was brought up in an office where violating Brady was a trial tactic,” said Barket, who previously worked as an assistant district attorney for Rice’s predecessor, Dillon. “[Hynes] clearly ran an office that condoned misconduct by his trial assistants. I think she was raised by Hynes and taught a system by Hynes.” Phillips wrote in the emailed statement that Barket is Rice’s “sworn political enemy.” In Nassau County, state statistics show a marked shift in case dispositions in the years under Rice’s stewardship. In the eight years before Rice took office, just over 21 percent of completed trials stemming from felony arrests resulted in acquittal. During Rice’s tenure, that same figure jumped to 30 percent. Suffolk County’s corresponding acquittal percentage has stayed mostly steady over both time periods, rising only from 26.1 percent to 26.6 percent. A spokesman for the Nassau County district attorney’s office, Shams Tarek, called those numbers “false” in a statement to Newsday and instead provided figures which excluded initial felony charges tried as misdemeanors. Those numbers still showed an acquittal rise during the Rice era, from 17.6% to 24.2%. Experts interviewed by Newsday said that the jump in acquittals was troubling and deserved scrutiny. “It could mean you’re trying difficult cases,” Pace Law Professor Gershman said. “Maybe these people aren’t as experienced or competent as they should be. Maybe there is lousy supervision in the office.” John Jay professor O’Donnell said reviewing trial statistics “is an opportunity to assess whether there is a sufficient cadre of skilled trial prosecutors in the office. It is absolutely inarguable that you would like to have the highest conviction rate possible in cases that you bring to trial, and a defendant having a one in three chance of winning a case is a concern.” Brady rules Rice, who was president of the District Attorneys Association of the State of New York until July, has bristled at the accusation that her own prosecutors do not adhere to the law. In August 2012, she fired back after top defense attorney Marvin Schechter penned an editorial in the New York Law Journal accusing local district attorneys of coaching their assistants to hide information favorable to the defense — a clear Brady violation. Rice’s written response called Schechter’s argument “offensive and inaccurate” and said that some Brady violations are human error. “I would have told him what I would do with a prosecutor who willfully and intentionally commits a Brady violation: I would fire him or her on the spot,” Rice wrote. The month following Rice’s vow, a judge removed one of her assistant district attorneys, Martin Meaney, from trying a homicide case because he failed to disclose that a security guard near a murder scene did not identify the defendant in a photo array. “It seems that that Brady violation, unfortunately, does put your credibility into issue before a trial,” Judge Alan L. Honorof told Meaney in the case of Jovany Henrius, who is charged with killing two men in the Woodbury home of his cousin, former NFL linebacker Jonathan Vilma. Touro professor Davis, after reviewing transcripts from the case at Newsday’s request, said the violation seemed clear to him. “This is a very obvious piece of evidence,” Davis said. “Even a layperson could see this.” Meaney, who at the time had been a Nassau County prosecutor for 24 years, had little defense. “With regard to the Brady violation, Judge, I don’t have much to say,” Meaney said in court. “I know the law in the area says that Brady has to be turned over in sufficient time for defense counsel to make use of it.” Judge Honorof, remarking that he and Meaney “have served together in the district attorney’s office,” said he had no choice but to believe his former colleague. “I have known him that long and have that high of a regard for his honesty and integrity,” Honorof said. “So if he tells me something, I’m going to believe him.” Following the remarks, Henrius’ attorney, Michael DerGarabedian, appealed to have Honorof removed from the case due to his relationship with Meaney. Though the appeal failed, Honorof voluntarily recused himself last March to “avoid any conflict or appearance of impropriety.” Tarek, the spokesman for the Nassau district attorney’s office, wrote in a statement to Newsday that Meaney had not been disciplined because he’d been exonerated by an in-house investigation. “We respectfully disagreed with the judge’s finding that this was Brady material and a thorough investigation found there was no willful wrongdoing on the prosecutor’s part,” Tarek said. To read the original comments on this story, click here to view the thread in Disqus. With Matt Clark and Adam Playford CORRECTION: A previous version of this story misstated Kathleen Rice’s status with the District Attorneys Association of the State of New York.

Sandy Stories

Long Islanders recount their struggles during and after Sandy in these exclusive interviews with News 12 Long Island. Click the camera icon in each story to see videos and photos.

Anthony D'Esposito

Fighting Floods and Fires

Chief Anthony D'Esposito of the Island Park Fire Department takes us back to the night of Superstorm Sandy when his department went beyond the call of duty to protect its community.

News 12 Long Island

Mayor Bill Biondi, First Assistant Chief Carlo Grover

Rooftop Rescuers

Superstorm Sandy’s storm surge blasted The village of Mastic Beach, forcing residents and their pets to their rooftops awaiting help. Two of the rescuers on the front line tell their stories of that night.

News 12 Long Island

David & Judy Lande

Still Not Home

On the night Superstorm Sandy hit Long Island, the Lande Family of Oceanside evacuated their home and met rushing flood waters at their front door. They struggled to make their way across the street, carrying what little they could salvage above their heads.

News 12 Long Island

Margarita & James Udall

Sandy Baby

Margarita and James Udall were looking forward to the end of October 2012 as Margarita was due to give birth to their first child. As her contractions and Superstorm Sandy’s landfall drew closer, they knew this delivery would be special.

News 12 Long Island

Gabrielle Fehling

Serious Surge

Gabrielle Fehling and her husband Mike own “Empire Kayaks” located on Barnum Island in Island Park. They have been through what they thought was every type of storm possible, and secured their stock of boats and kayaks to evacuate. Gabrielle wasn’t prepared for what she would find when she returned, but that didn’t stop her from coming back better and stronger.

News 12 Long Island

Michelle Mittleman

Empty Lot

The property on which Michelle Mittleman’s former home stood is a vacant lot in a neighborhood littered with condemned homes. Despite having full flood coverage, her insurance company denied her claim.

News 12 Long Island

James Salazar, Anthony Bocchimuzzo

Answering The Call

Police 911 Operators, Anthony Bocchimuzzo & James Salazar, are used to emergencies. But when Superstorm Sandy hit Long Island, no matter how fast they worked the numbers of callers in peril kept growing.

News 12 Long Island

Stacy and Ralph Anselmo

Sunshine Behind The Storm

Stacy and Ralph Anselmo always knew they would get married in Long Beach. When their waterfront dream home was destroyed by Superstorm Sandy and rebuilding stalled in bureaucracy, they had an idea.

News 12 Long Island

Deborah Kirnon

Nowhere To Turn

After Superstorm Sandy left Long Island crippled, Deborah Kirnon used her position as Director of Parish Outreach at St. Anne's church in Brentwood to help thousands of Long Island’s neediest.

News 12 Long Island

Anthony Eramo

Taking A Chance

Anthony Eramo of Long Beach rode out Superstorm Sandy with his children in their home. What he saw when his family walked outside after the storm passed has him regretting the decision not to evacuate to this day.

News 12 Long Island

Two years after Sandy: NYC recovers

This interactive project highlights dramatic images from the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy and how those same sites look two years later. Photos on the left show damage directly after the storm; photos on the right show those areas now. Move the slider — the vertical divider between each set of photos — left or right for the full photo. Mobile users, the original photo will be stacked on top of the current photo.

First destroyed by fire, then demolished, the Gotham Walk section of Breezy Point has largely been rebuilt.

Water flooded the entrance to The Plaza Shops at One New York Plaza during Sandy.

A house on Kissam Avenue that had its first floor washed away by the storm was torn down.

Some of the Jamaica Walk houses that caught fire during Sandy have been demolished and others rebuilt.

Water flooded the South Street Seaport, causing extensive damage and knocking out power to many of the businesses.

Clear streets today show no signs of the submerged cars on Ave. C and 7th St. after Sandy.

Joe & John Toto’s Restaurant and Bar was severely damaged by Sandy.

Submerged cars were trapped at the entrance to a flooded underpass on South William Street, near Broad Street.

Many of the Ocean Avenue houses that burned down during Sandy have been rebuilt.

Rebuilding has begun in the Neponsit area of Rockaway.

Two years after Sandy

This interactive project highlights Long Island’s recovery process after superstorm Sandy. Photos on the left show sites that were dramatically altered by the storm and how they looked one year later; photos on the right show those areas now. Move the slider — the vertical divider between each set of photos — left or right for the full photo. Mobile users, the original image will appear stacked on top of the current image.

Use the navigation tools at the top of the page to see then and now photos from one year and six months after Sandy.

A house on Narraganset Avenue that was raised in 2013 is shown a year later.

Heading into the first summer after Sandy, outdoor nightclub Tropix on the Mile was scrambling to open before Memorial Day. It is since back in business.

Last year, the Albert family was living in a trailer and had just raised its house on Araca Road eight feet above the flood plain. They are now living back at home and hoping to have a stairway installed in the near future.

First destroyed by fire, then demolished, the Gotham Walk section of Breezy Point has largely been rebuilt.

When water from Moriches Bay surged over the area of land between Ocean Avenue and Inletview Place, it swept away entire walls of bay-facing houses. Some are not yet rebuilt.

Anthony Fiore, owner of Fiore Fish Market, is still waiting for a NY Rising award to rebuild the business.

A newly built, elevated home on Riviera Drive replaces a home that was damaged by the storm. A year ago, many houses in the area were still empty and in disrepair.