One man’s rise shines light on LI’s corrosive system

Gary Melius goes from street tough to owner of Oheka Castle

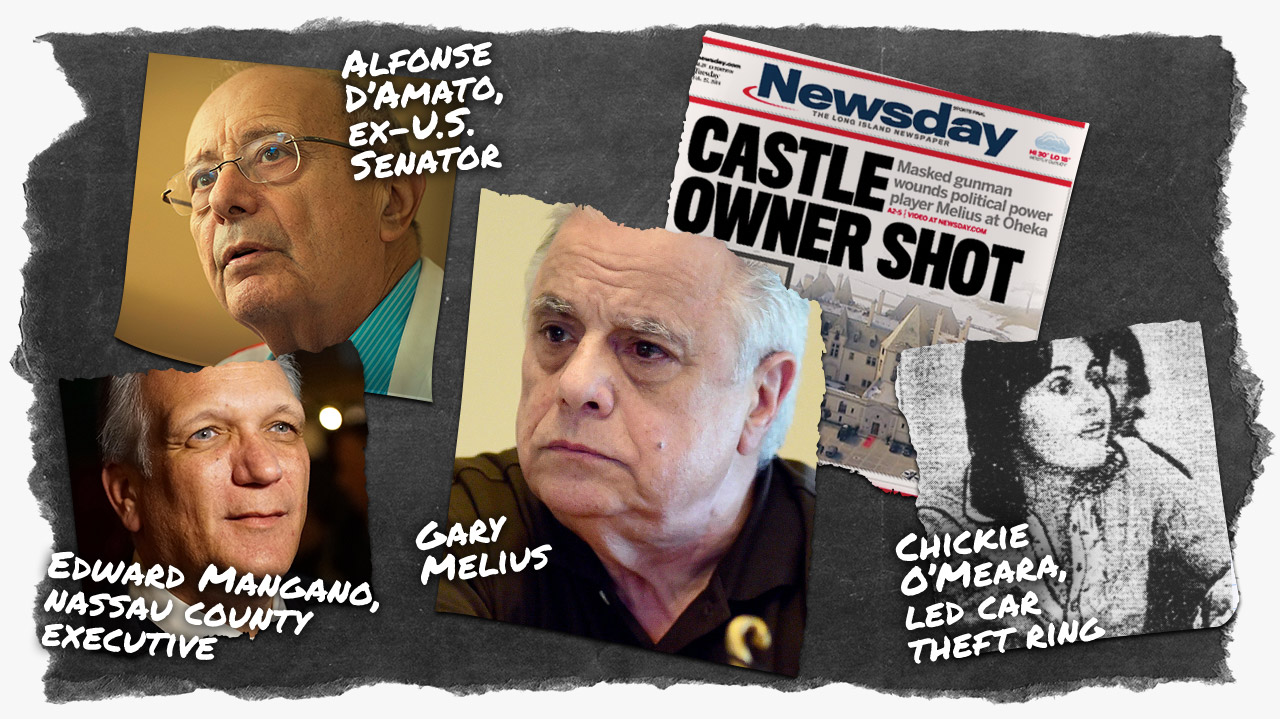

Shortly after noon on the near-freezing day of Feb. 24, 2014, real estate developer Gary Melius started his Mercedes-Benz in the valet parking lot behind Oheka Castle, the palatial Huntington hotel and event center he owns and calls home.

A masked man crept from a Jeep Cherokee parked nearby, put a pistol to the driver’s window and pulled the trigger, wounding Melius in the left forehead.

In his fragmented recollection, Melius heard a ringing in his ear and staggered to the castle, where he swiped himself in, put a wet towel to his head and asked his daughter to drive him to a hospital, later bragging that he “showed no fear.”

His still-unsolved shooting was treated like the attempted assassination of a statesman. Suffolk police officers assumed an imposing guard at the snow-specked castle while a roster of Long Island’s most influential officials at the time visited him at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset.

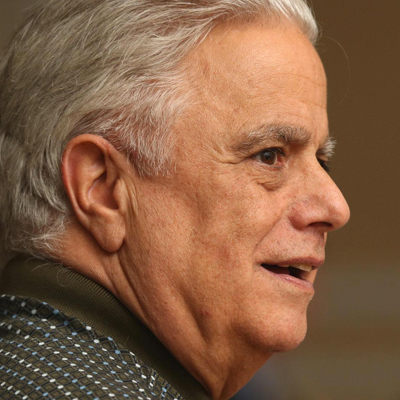

The visitors included the two county executives, Suffolk’s Steve Bellone, a Democrat, and Edward Mangano, a Republican; Reps. Peter King, a Republican, and Steve Israel, a Democrat; former Freeport Mayor Andrew Hardwick; acting Nassau Police Commissioner Thomas Krumpter; Nassau Sheriff Michael Sposato; Nassau’s top administrative judge, Thomas Adams; Suffolk Supreme Court Justice Thomas Whelan; and, overshadowing them all in wide-ranging influence, former Sen. Alfonse D’Amato.

The attempted murder in broad daylight of a developer with powerful connections, captured by surveillance footage on his castle grounds, briefly made national news. It loomed larger in Long Island’s political world.

Gary Lewi, D’Amato’s former press secretary who has also represented Melius, compared the incident with “Robert Moses being gunned down in the parking lot of Jones Beach.”

However overblown the link to the legendary master builder, Melius’ broad reach over Long Island politics, law enforcement and civic life has in many ways been unparalleled.

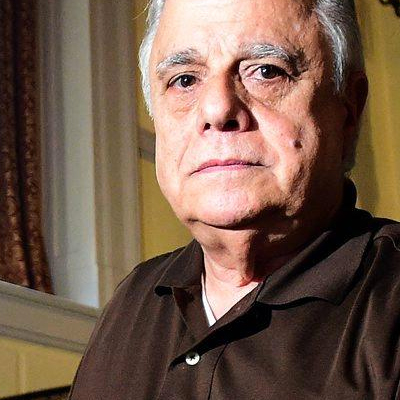

With a mix of canniness, unpolished charm and threats and taunts, Melius, now 73, has transformed himself from a teenage street tough out of West Hempstead to owner of the castle that became Long Island’s unofficial political clubhouse. His networking has been prodigious, allowing Oheka to flower. He has been the host at years of law enforcement parties at the castle, where, guests said, cops and FBI agents ate and drank for free.

His foundation has donated more than $2.8 million to roughly 500 mostly local charities. In addition, Melius, his family, businesses and employees have contributed at least $1.3 million to politicians, several of whom were behind governmental actions worth millions to him.

Never a Democratic or Republican functionary much less a party boss, Melius made his way from the outside in — as a player with powerful friends and a practical understanding of the day-to-day workings of Long Island’s cozy, transactional politics. As such, his life reveals a detailed picture of how the system functions.

It is a system facing crisis. For decades, scandal has been a steady current in Long Island politics, but last year it blew out fuses. By Newsday’s count, in 2017, about 40 public officials, politicians and cops and other government workers were indicted, imprisoned, or forced from their jobs by ethical transgressions and scandals. That capped a 10-year period with more than twice that number of cases.

High-profile year of political corruption

Among them was Mangano, whom Melius has described as “the best political guy” and whose federal trial is scheduled to begin in March. He is charged with giving government contracts to a restaurateur whose favors included employing his wife, Linda, as a food taster for a total of $450,000 over more than four years; prosecutors allege that she performed little or no work. Mangano and his wife have pleaded not guilty.

They also include Edward Walsh, the influential former chief of the Suffolk Conservative Party, who is serving a 2-year sentence for theft of government funds and wire fraud for golfing, gambling and doing political work when he was supposed to be on the job at the Suffolk County jail. The charges included an instance in which prosecutors said Walsh provided support to Melius at a private business meeting when he should have been working at the jail.

Former Suffolk Police Chief James Burke is serving 46 months for pummeling an addict who stole his porn-filled duffel bag and trying to cover up the beating. In arguing for a stiff sentence, federal prosecutors noted that Burke bragged about his actions to fellow cops at an Oheka Christmas party.

The year’s indictment roster included John Venditto, who resigned as Oyster Bay supervisor between his two corruption indictments, the second of which also ensnared several past and then-town officials; Gerard Terry, who while head of North Hempstead’s Democrats held down five government jobs and pleaded guilty to not paying income taxes on them; and Hempstead Councilman Edward Ambrosino, a prominent Republican who was indicted on charges of failing to pay taxes on his earnings as an attorney for the Nassau Industrial Development Agency and the Nassau Local Economic Assistance Corp.

Capping the year was the indictment and subsequent resignation of Suffolk’s longtime district attorney, Thomas Spota, who, with the head of his anti-corruption unit, was charged with conspiracy and obstruction of justice, accused of helping Burke in the cover-up. Spota, who headed the still-unsuccessful investigation into Melius’ shooting, and his corruption-unit chief, Christopher McPartland, have pleaded not guilty.

Ambrosino, Venditto and the other Oyster Bay officials have also pleaded not guilty.

Federal investigators have looked into matters involving Melius: One concerning fees that he and associates collected from state court appointments and another involving the Elena Melius Foundation, which is named for his mother. But Melius has never faced political corruption charges and is adamant about his integrity. Three years ago, he said, FBI agents hauled 180 boxes out of Oheka. The FBI has declined to comment.

“I haven’t done one thing wrong,” Melius said in a meeting with Newsday editors last April. “The federal government — three years to investigate me — you know what they came back with? Nothing.”

“I am a very honorable person,” he continued. “Whatever I say, I do the best I can and nobody got robbed from me.”

Melius was asked in April if he would be interviewed substantively by Newsday reporters for this project. He was asked again on Feb. 13 if he would consent to an interview. He responded that he would first want to read all of the stories. Newsday’s policy is not to do so.

This past November, voters elected several new office holders who carried the banner of reform, including Nassau County Executive Laura Curran, Suffolk County District Attorney Timothy Sini and Hempstead Town Supervisor Laura Gillen. Melius’ half-century-long rise shows how broad and entrenched the system is and how hard it may be to exact lasting change.

A contradictory picture

As cops, reporters and an array of Long Island power brokers massed outside the hospital where doctors were working to save Melius’ left eye, his friends said they were mystified by the attack.

“No one could think of anyone that would want to kill Gary,” Steven Schlesinger, a powerful Nassau Democratic Party lawyer told a television reporter.

In many ways, the sentiment was understandable. There are plenty of campaign contributors who send money to politicians, but few who go puppy shopping with them, as Melius did with Mangano.

At Oheka, he is known as an affable, self-effacing bon vivant, telling jokes in a blunt cadence while wearing short sleeves that display faded tattoos. And his private enjoyments can be endearing. His fellow up-from-nothing mansion owner John Nasseff fondly recalls dinners with the Meliuses at his Minnesota home where they enjoyed performances by hired singers and magicians.

“To know him is to love him,” said D’Amato after visiting Melius’ bedside.

But a far more complicated and contradictory picture of Melius emerges in Newsday’s extensive examination.

The picture took shape through a mosaic of sources: more than 500 interviews and tens of thousands of pages of records. They include long-overlooked files that cover Melius’ early criminal career; documents from more than 200 often rancorous court cases with business partners, neighbors, government agencies, and even his dry cleaner; an investigation by the National Indian Gaming Commission, a federal agency whose staff recommended that Melius be found unfit to run a casino; and a string of business failures and gambling debts that left his creditors with as little as 5 cents on the dollar.

The generosity is certainly there. So is the likable persona recalled by friends.

But that can dissolve on a dime, and in one infamous case his fierce focus led to the arrest of a man with learning disabilities, Randy White, who unwittingly wound up on the wrong side of one of Melius’ political schemes.

Often overshadowed by his restoration of the resplendent Oheka and his munificent charitable donations, this more troubling side surfaces most tellingly in Long Island’s public arena.

Benefits of the system

Unfolding in records and interviews is something akin to an American dream success story, albeit of the complicated, less sanguine variety captured in novels such as “The Great Gatsby.” There, the protagonist emerges from obscure beginnings with the help of questionable connections offered by his 1920s Jazz Age circle and achieves a success captured in the grandeur of his North Shore mansion.

Melius is a far cry from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s glamorous, tragic protagonist. But for a half-century, Long Island’s world of politics and power has provided him an equivalent circle, supplying connections, opportunities and the playing field of a tumultuous life, grand mansion included.

When Melius maneuvered within Long Island’s bounds, he reaped millions through zoning changes, legal settlements, contracts and court appointments. When he tried his luck outside it, he often stumbled through an assortment of failures, from a foray into boxing promotion to trying to partner in casino management upstate and more.

Those are stories in themselves, but more importantly they point to what was absent as Melius tried to succeed on his own: the sustaining power of Long Island’s political network.

Through Melius, Newsday’s investigation reveals the benefits that system can provide:

- Early on, a young Melius faced five sets of criminal charges, but after he hired a politically connected Long Island lawyer, felonies morphed into misdemeanors, near certain jail time turned into light fines and probation, probation got cut short, and his most serious conviction was expunged.

- As Melius, his employees, businesses and family members were contributing at least $1.3 million to political campaigns, he was lifted out of real estate problems at Oheka and in Freeport through favorable government decisions worth millions. In Freeport, Nassau County bought his failing property based on a questionable valuation commissioned by the county that was three times higher than the property’s assessed value.

- As he feted cops and FBI agents at Oheka, Melius became involved in episodes that called into question the integrity of law enforcement agencies in which his friends held key positions. Melius championed the hiring of Thomas Dale as Nassau police commissioner. Later, he called Dale to say Andrew Hardwick’s county executive campaign wanted to file a perjury charge against Randy White, the man with learning disabilities who had testified in a case that threatened Melius’ bid to influence the 2013 election. Dale had White arrested — on grounds so suspect the county eventually paid White a $295,000 settlement — and was later forced out for doing so. Freeport Village Attorney Howard Colton filed a police complaint in 2009 alleging that Melius threatened to have him indicted, citing Melius’ relationships with the Nassau district attorney’s office and its chief investigator. Colton alleged they were acting as Melius’ “private police force.”

- The Nassau and Suffolk leaders of the influential Independence Party worked as Oheka employees over the years. Melius was named the party’s “chief adviser” as part of an effort to take the party national, and he and his daughter reaped hundreds of thousands of dollars in appointments from a judge whose political career was resurrected by the party.

In the mix of Melius’ business associates were: a Howard Beach car thief whose son was killed in a mob hit, a charismatic loan shark, and a Japanese businessman widely reported to have ties to the Yakuza crime organization.

Critical of media coverage

The incongruities in the arc of Melius’ life have been plentiful, notably the juxtaposition of relationships with Long Island government and law enforcement officials and sporadic associations with unsavory characters.

At a meeting with editors last April, Melius criticized coverage of him in Newsday, which has published articles about his foundation, receiverships he and his daughter were awarded by judges, and other matters.

Melius last year accused Newsday of unfairly attacking him, saying the newspaper had featured him in 170 stories since he was shot — 16 on the front page — that, he said, had exacted a toll on his business and family.

Also last year, Melius threatened a Newsday reporter who worked on a story about his effort to get the Nassau County Legislature to approve a sewer hookup for a condominium development at Oheka Castle.

He agreed to an interview at Oheka in 2014 with Newsday investigative reporters for this story but declined to discuss many topics. Melius refused further substantive interviews with team members, although he answered some questions from a Newsday business reporter last summer before a legal proceeding began.

“I am broke now, I mean I have lost everything, thanks to the paper,” he told the editors last April, explaining his reticence to talk further. “I am none of the things you have me down as. I am not a power broker; I am a nice guy.”

Melius’ life is quieter now and he complained to Newsday editors of the fallout from the shooting: seizures and that he can’t drink, smoke cigars or drive anymore.

“They only harpoon the whale when he surfaces, and it’s true — look what happened to me,” Melius remarked. “I will never do that again, getting shot in the head.”

As for the shooting investigation, Justin Meyers, chief of staff for Suffolk County District Attorney Timothy Sini, said: “We wouldn’t discuss an open investigation but I can assure you it remains open and the police department continues to pursue the case.”

‘Troubled youth’

Melius’ Long Island story began like many others in the 1950s, when droves of city dwellers, many of them Irish, Jewish or Italian, flooded what had mostly been farmland, more than doubling the Island’s population in two decades. It amounted to a second great migration by families that emigrated from Europe in the 19th and early 20th century.

When Melius was in third grade, his family, which included two sisters and an older brother, moved from Jackson Heights, Queens, to a small home on West Hempstead’s Maplewood Avenue.

He would establish the multimillion-dollar Elena Melius Foundation in honor of his mother, a daughter of Italian immigrants whom he venerated. He has characterized his father, a truck driver, as abusive, he once told Newsday.

As described by his teenage sweetheart, Melius was the most charming rogue on the block. Marilyn Brown Ryder, who dated him when she was 16 in 1960, remembers the handsome, dark-eyed leader of a crew of trouble-seeking boys, including her future husband, Robert Ryder, who mostly hung out at the neighborhood bowling alley. “They were the talk of West Hempstead,” she recalled.

But while his friends looked for fights, Marilyn Ryder described Melius as something more, smart and savvy and able to “B.S. anyone.”

Nonetheless, Melius said in a Newsday interview that he dropped out of West Hempstead Junior High before ninth grade.

In 1962, he and Robert Ryder were arrested and charged with petty larceny for stealing tires, according to the staff findings of the National Indian Gaming Commission, which years later chronicled his criminal history as it weighed his suitability to manage a casino. The disposition of those charges is unknown.

The next year they were busted for a felony marked by ruthlessness and the incongruous generosity that has typified Melius.

Just short of his 19th birthday, he, Ryder and two others “slapped, choked and threatened with death” a West Hempstead hitchhiker from whom they stole $40, according to a Newsday report. But the muggers left their victim with $10 for carfare home.

Melius pleaded guilty to felony second-degree attempted grand larceny, according to the Indian commission memo. He was sentenced to up to 5 years, with the penalty suspended, the memo stated, meaning he served no time.

Melius has described his criminal past as “colorful,” chalking it up to his “troubled youth.” But criminal records, court transcripts and interviews indicate that he graduated from local hooliganism to more sophisticated schemes, one with organized crime links.

Befriending an officer

By the early ’70s, Melius was stumbling through what he has called a “whole list of failures,” such as Gary’s Tree Service and Gary’s Pizza Oven, and trying to build a modest contracting company called Eastport Construction.

Around this time, Nassau County Police Officer James Mileo later recalled, he pulled over Melius in Manhasset for speeding.

Now in his 80s, Mileo told this story from Florida: Melius talked fast, quickly learned that the cop had money woes, and offered him part-time work at Eastport, which Mileo accepted after forgetting about the speeding.

Mileo got to know his new boss, and real estate records show that at one point the cop deeded him a house in Seaford. He recalled a day when Melius picked him up at a job and drove to a Brooklyn restaurant.

There, Mileo said, Melius joined a man at a corner table whom the cop recognized as Carmine “The Snake” Persico, the Colombo crime family boss whose foreboding, angular features were captured regularly in New York tabloids.

After 10 minutes, Melius returned to their table, Mileo said.

Mileo said he took the display as at least partly for his benefit. “He wanted to get me on the illegal side of things,” he said.

Fran Arello, then a rookie with Nassau police’s organized crime squad, said that a Colombo-affiliated informant reported that Mileo was stealing construction equipment from parkways and shaking down motorists with Melius’ help.

Arello recalled scoping out Melius’ contracting storefront in Valley Stream before she donned a red wig and jammed a tissue-wrapped microphone into the bosom of a tightfitting dress one night in September 1971.

She drove a Cadillac convertible down Roslyn Road, where her informant had set up Mileo by telling him a heroin courier with a “very rich father” would be driving by.

Mileo pulled over the Cadillac, rifled under a floor mat and found packets of milk sugar that passed for the drug, Arello recalled. She said Mileo offered to let her go for $15,000 and then released her to retrieve the cash.

After collecting marked bills in an envelope from detectives outside a nearby bank, she went to a meeting point across from a synagogue on Roslyn Road where Melius, whom Arello called the scheme’s “bagman,” was waiting and took the cash, she said. A short time later, he and Mileo were arrested and charged with felony grand larceny.

During the episode, there was another person in the car: the mob informant, who sat in the shotgun seat.

She was a gangster with a bouffant who ran a racket with three female lieutenants and whom Arello remembered as foul-mouthed, funny and smart, and also as someone who would “shoot you in a heartbeat.” Her name was Ellen “Chickie” O’Meara.

O’Meara was a cinematic figure undiscovered by Hollywood. A product of private schools in Queens and Long Island, she traced Mafia ties to her grandfather, whom she described in an interview as an associate of the seminal mobster Vito Genovese.

Besides the Colombo family, O’Meara told a reporter she also worked for Gambinos. She had been locked up dozens of times by 1970 for offenses as diverse as lifting fur coats and fixing college basketball games, according to contemporaneous news reports.

That summer, according to O’Meara’s later testimony, her primary racket was an interstate theft ring specializing in construction equipment and Cadillacs. She ran it with her three lieutenants and a crew of male worker bees.

Word of the operation got around, though, and shortly before the Melius-Mileo busts, O’Meara was quietly arrested and turned; her bid for leniency put her in Arello’s Cadillac on Roslyn Road.

Cliff Schmidt, then the Nassau Police Benevolent Association’s second vice president, recalled sitting with Mileo in an interrogation room and his heart breaking as the cop owned up. “He was a great officer,” Schmidt said of Mileo, who he believed was likely “entranced with Melius.”

“I wish he would have never have gotten involved with him,” he said.

More than four decades later, Mileo could not qualify for a job as an unarmed security guard in Florida.

Testimony on car theft ring

Weeks after Melius and Mileo were arrested, federal and New York City prosecutors moved on O’Meara’s entire ring, sweeping up 16 suspects, including Melius again.

A New York Times account described the crew as an element of “a much more potent faction of organized crime that operated in many states.”

O’Meara and others detailed the operation during a related federal trial in Virginia against buyers of her stolen haul. According to her testimony and others’, construction site managers were complicit, deals went down under city bridges, and hot machinery was stashed at a Sheepshead Bay marina. Witnesses testified of threats and visits from O’Meara’s intimidators, her demands for money she said was needed to pay off a judge and an apparent attempt to burn evidence as authorities closed in.

Granted federal immunity for her testimony, O’Meara used simple terms to describe Melius’ role. “He is the one who steals the Cadillacs,” she testified in court.

With car theft rampant on Long Island and often mob-controlled, O’Meara and others described the street outside Melius’ home as lined with stolen, nearly new Cadillacs.

She recounted a negotiation at a motel near LaGuardia Airport, where a couple of out-of-state businessmen attempted to pay for a Cadillac with a cashier’s check. “Gary said they wouldn’t take no check, that they would only take cash,” O’Meara testified.

When the buyers returned with proper payment, Melius and an associate identified only as Pauley led them to his fleet, O’Meara testified. “Gary gave me the keys to give them,” O’Meara said. “They gave me the cash in an envelope, and Gary counted it out, and that was it.”

O’Meara served 3 years in prison. Upon release she found a home in Long Island politics.

She became an aide to then-state Sen. Karen Burstein of Woodmere, who said O’Meara caught her eye as a leader in prison reform from the inside. Burstein said that she believed that O’Meara “might still be friendly with some people,” but was through with the rackets.

That may have been a miscalculation. In 1976, O’Meara was arrested and charged with soliciting a cash bribe in exchange for using her position to help secure parole for an inmate, according to a news report. The bribe allegedly was paid directly to her bookie. O’Meara was found guilty, but the conviction was overturned because of a wiretap the courts ruled illegal.

Along the way, she found Judaism. She died last year, said her rabbi, Yitzchok Frankel.

Meeting influential lawyer

In 1971, Melius faced grim prospects. At 27, he had been arrested five times. The hitchhiker mugging had resulted in a guilty plea to a felony.

He still faced judgment day on the cases involving the shakedown of the undercover cop and the car theft ring. And unknown to him, there was a Nassau County judge who wanted him imprisoned.

He needed legal magic, and found it in a young lawyer named Richard Hartman.

Hartman was a well-connected, self-destructive math genius who was born a Brahmin in Long Island politics.

His father was William Hartman, a one-time state senator, GOP committeeman and aide to Assembly Speaker Joseph Carlino. Carlino was a seminal leader of Nassau’s formidable party organization, which at one point caused Ronald Reagan to beam, “When a Republican dies and goes to heaven, it looks a lot like Nassau County.”

Before his father pushed him into law, Richard Hartman dreamed of teaching mathematics, his sister Lynn Alpert said.

He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology but left before graduating and then earned a degree at New York Law School. He worked briefly as a Nassau prosecutor and a lawyer in traffic court, where Melius met him.

Soon, though, he leapt into representing the police unions that cover both Long Island county departments and influence life — and taxes — here to this day. He also represented dozens of other unions, politicians and mobsters.

Among the latter was an admitted contract killer named John Alite, a mob associate who became a witness for federal prosecutors. In an interview with Newsday, Alite described Hartman easily arranging a plea deal that kept him out of jail for carrying a handgun in an Island Park nightclub.

He said he still recalls how Hartman explained his success: “It’s who I know, it’s not what I know.”

Hartman’s headquarters at 300 Old Country Rd. in Mineola was a white stucco building recalled as a dump by nearly everybody who encountered it. Melius’ contracting company eventually became a tenant.

Hartman’s unmarked domain, a raucous all-hours hub of political power, was on the second floor.

A secretary, Patricia Phillips Hartman, no relation to her boss, whom she called “maniacal,” recalled: “He would pound on the desk and yell for a girl. ‘Girl! Girl!’ Everybody would bump into each other trying to get into that office quick enough.”

Former Suffolk Police Commissioner Gene Kelly, who worked briefly for Hartman, said he “never had a clock” and would call on work matters at 3 a.m., something that drove some to quit.

Hartman’s then-girlfriend, Patricia Motamed, a secretary on the overnight shift, recalled that as his practice grew, Hartman hired so many new attorneys that Melius was enlisted to build each an office on the roof.

“It really looked like a shack and a dump,” Motamed said.

She also measured the fast-forming friendship between the on-the-rise police lawyer and his frequent client.

“You have two people who collided, one who was brilliant, almost a savant,” said Motamed, “and one who was a true, local thug.”

Change in fortune

The vagaries of record retention and sealed files concerning decades-old cases make it impossible to ascertain Hartman’s full representation of Melius.

What’s clear is that after meeting Hartman, Melius was the beneficiary of numerous fortuitous legal developments.

His 1964 felony plea in the hitchhiker case was a seemingly indelible mark. But in September 1970, nearly seven years later, it disappeared, according to the Indian Gaming Commission memo. The outcome of the case was erased and records of it sealed.

Melius was the unusual beneficiary of a statute that was touted as a means of helping teenagers start fresh after an early arrest. Melius was a good deal older in 1970 — 26 — and the statute makes no mention of a retroactive youthful adjudication, which the federal memo stated he received.

And at the time, according to O’Meara’s testimony, he was stealing cars for her ring.

Under the statute, a candidate for adjudication had to be recommended by a district attorney, grand jury or judge and investigated by a probation agency.

Because the records are sealed, it’s unknown who recommended the treatment in Melius’ case, but the circumstances were noted by Nassau County Judge William J. Sullivan when Melius appeared before him on St. Patrick’s Day 1972.

He was awaiting sentencing in the attempted shakedown of the undercover police officer, for which he had been charged with grand larceny, according to court documents.

Melius had agreed to a deal in which he would plead guilty to a misdemeanor. Melius’ lawyer, Theodore Daniels, argued for probation.

But that day, Sullivan received a probation report describing Melius as unreformed. In scathing remarks reflected in a court transcript, he told Melius, “The probation report indicates you still keep undesirable company, that you are greedy for money, and I am satisfied that you are the one that got your co-defendant in trouble.”

The judge called the erasure of Melius’ felony in the hitchhiker’s mugging a “break,” but, he told him, “You didn’t learn anything from that.”

Despite the plea deal, Sullivan said, “I think that the only way to straighten you out and to get you away from the associations that you have been keeping, is to take you out of circulation for a short while.”

Facing certain jail time, Melius withdrew his guilty plea and turned to a new lawyer, Hartman.

Sullivan was a rare Democrat among Nassau judges. In Hartman, Melius retained a lawyer with deep GOP connections.

By the next court date a month later, Sullivan had been replaced by a new judge, Albert A. Oppido, a Republican. The change of judges is not explained in surviving court records, and both Sullivan and Oppido are deceased.

A transcript shows Oppido taking a stance diametrically opposed to Sullivan’s. The judge allowed Melius to plead to misdemeanor attempted grand larceny in the third degree, according to court documents. He sentenced Melius to 3 years’ probation and a $1,000 fine.

The National Indian Gaming Commission memo shows Melius again the benefactor of lenient sentencing in Queens, where he faced felony charges including criminal possession of stolen property for his role in O’Meara’s ring. Melius pleaded guilty to misdemeanor conspiracy and was fined $500.

Citing FBI records, the memo recorded one last arrest by Nassau police in October 1971, that led to grand larceny charges, which were dismissed. The memo did not describe the activity that led to the arrest or why the charges were dismissed.

By February 1974, Melius’ arrest record had resulted in no known prison time, with his single felony conviction erased, according to the federal gaming commission memo. It totaled his fines at $1,500.

Melius bore one last legal burden: more than a year still left on his probation resulting from his attempted-grand-larceny plea in the shakedown of the undercover cop.

This was more than an inconvenience. Probationers sometimes receive surprise home visits from probation officers and risk jail for any violation.

Escaping the obligation required a recommendation from probation officials who two years earlier had found him unreformed, and then a judge’s OK.

Hartman was familiar with the heavily politicized department. His sister was an officer there and he would represent its union for years.

The role that politics played in Nassau probation in ’70s

In February 1974, Melius was the subject of a new probation department report that noted a remarkable transformation. It concluded that he had “demonstrated a complete change of attitude and behavior,” and had “concrete roots in the community and is seen as a responsible father and citizen. He is conscientious and ambitious with his business.”

The author of the report was John Siarkowski, a longtime probation officer who has been active in the Republican Party. He declined to comment for this story. One of those signing off on it was Daniel Ebbin, the now-deceased longtime chairman of the probation officers’ union.

Perhaps there was truth to the report, but when told of it, Motamed said she recognized the handiwork of her old boyfriend. “That was all Richard,” she said. “He fixed all that.”

The probation department recommended Melius’ discharge and Oppido signed it. The once-accused Cadillac thief and shakedown artist left Nassau Supreme Court an unencumbered man.

Long Island power established

Three decades later, developer Wilbur Breslin and his lawyer drove to the same courthouse to do battle with Melius, by then also a prominent developer.

In the parking lot, they noticed Melius’ car in the chief judge’s spot.

“We’re dead,” Breslin recalled saying. The sinking feeling intensified in Judge William LaMarca’s courtroom, where Melius and his lawyer were seated.

As Breslin remembers it, the courtroom door swung open and in came a robed judge who greeted Melius with an enthusiastic: “Hi, Gary!”

Then the door swung open again, and another smiling face emerged — that of Al D’Amato. He delivered kisses to LaMarca, Melius and Melius’ attorney, Marlene Budd, according to an attorney who was there.

Melius had sued Breslin, seeking repayment of a loan and a broker’s commission, on which Melius said they had orally agreed.

As Breslin had gloomily forecast, the case went south for him. In his ruling in 2005, LaMarca said contradictory testimony by Breslin and Melius left him having to weigh whose was more believable. He said he found Melius a “more credible witness” based on other witnesses’ testimony.

Breslin appealed the award of the loan, and a state appellate court in Brooklyn overturned LaMarca’s decision, finding that Melius’ argument hinged on a complicated “kickback scheme, which was illegal and unenforceable.”

LaMarca’s decision on the loan, they determined, was “contrary to the weight of the credible evidence.”

It was a loss for Melius, but it proved a contrary point: His influence on Long Island had grown far more than could have been expected once upon a time.

Intro:

Intro: Video:

Video: Chapter 1:

Chapter 1: Chapter 2:

Chapter 2: Chapter 3:

Chapter 3: Chapter 4:

Chapter 4: Chapter 5:

Chapter 5: Chapter 6:

Chapter 6: Chapter 7:

Chapter 7: