With new players, will LI’s entrenched system survive?

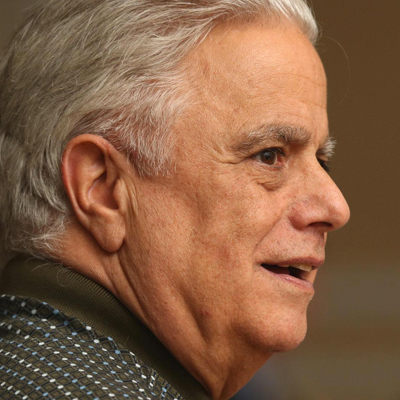

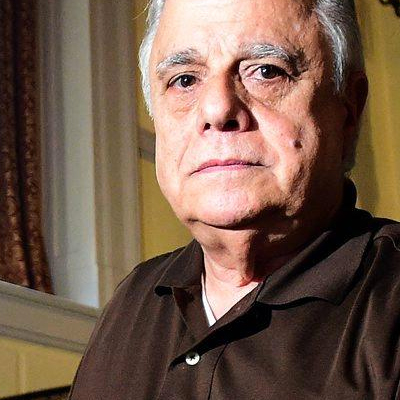

Gary Melius and the two tours of Oheka

Oheka Castle’s grand ballroom has been home to decades of fundraisers, weddings and parties for Long Island’s elite. In a small, linen-white dining room nearby, intimate networking lunches hosted by the influential Independence Party have drawn a steady stream of judges and law clerks. Down in the basement is what the castle’s proud proprietor, Gary Melius, calls his “man cave,” where some of the Island’s most powerful figures have smoked cigars and traded stories.

The castle has stood unrivaled as an expression of power on Long Island, and its bonding rituals provide a blueprint of how local influence operates, bearing fruit for Melius, his allies and many others. Whatever it costs the public, for those in power the system works.

The grand tour

Melius nearly lost his life in the shadow of his greatest success.

From the day he bought the abandoned castle, in 1984, Melius dedicated himself to restoring Oheka. He sold it in 1988 for $22.5 million to a Japanese billionaire accused of negligence in a hotel fire that killed 33 people, and years later bought it back from the businessman’s family for a third of that recorded price.

He was cited for ignoring fire safety and zoning laws and fought his neighbors, but after an aggressive political and public relations campaign, he won approval from Huntington officials he had supported to operate the castle as a commercial enterprise. Over the years, he said, he had invested millions renovating the castle, trying to recapture its original look.

He transformed what was then a 127-room mansion into an exclusive setting for lavish wedding receptions, the home of a high-end restaurant and boutique hotel, and a mingling ground for Long Island’s political, law enforcement and judicial elite.

A night at the hotel can cost more than $1,000, a catered event tens of thousands — up to $500 a head, in addition to a rental fee of up to $12,000. Restaurant guests can sample appetizers like lobster meatballs for $20 or steak entrees for up to $55.

The curious can book tours, with prices ranging from $15 to $100, according to Oheka’s website.

There’s a lot to see.

Start at the main entrance, where the marble steps, wrought-iron railings of the grand staircase, and shimmering crystal chandelier offer an expansive introduction to a mansion where F. Scott Fitzgerald was supposed to have gotten inspiration for Jay Gatsby’s fantasy palace in fictional West Egg, Long Island.

These days, it has been used as a location for Taylor Swift’s 2014 “Blank Space” video about a woman living the Gatsby life who unleashes her fury on a cheating beau in, of all places, a castle parking lot.

Just outside the castle are the gardens and Great Lawn, where Melius holds an annual Garden Party hosted by Friends of Oheka, a nonprofit formed to raise restoration money and public awareness of the castle. After buying tickets, party guests may rent antique Gatsby-style attire and props, like tommy guns, through an Oheka website.

Musicologist Roger Hall, who had lived as a student at the Eastern Military Academy when it was located at Oheka, created a website called “Memories of Oheka.” On it, and in a subsequent interview, he described a 2004 garden party where, he said, Huntington Councilman Mark Cuthbertson played Jay Gatsby. Cuthbertson said he did not remember doing so.

The formal gardens, with eight reflecting pools, three fountains and assorted statuary, are also a popular spot for weddings, among them those of the singer Kevin Jonas; Anthony Weiner and Huma Abedin in a ceremony officiated by former President Bill Clinton; and the late mob boss John Gotti’s grandson, John Agnello, with his proud mother, Victoria Gotti, looking on.

The 23-foot-high Grand Ballroom, lit by crystal and silver wall sconces, dominates the second floor. The sleek bar and restaurant are open to the public, and Melius often stops in to greet guests, on occasion showing them just where in the head he was shot.

In the morning, guests can breakfast in the yellow Terrace Room, added to accommodate larger events, or stroll amid the gardens.

Oheka, Melius has said, “is a place of happiness.”

The insider’s tour

But there’s another tour of Oheka that can be constructed, shaped by the workings of Long Island politics.

This is a more private world of cigar parties, man-cave gatherings, power lunches and political and judicial candidate screenings, over which Melius has at times presided, where local players forge relationships and cut deals outside public view.

Politically, the result is something in which Oheka has served less as a backdrop than an agent.

“Politics is a perception business, and if you can represent yourself as someone who can move votes or move money, or both, you’re powerful,” said Jay Jacobs, the Nassau Democratic leader with whom Melius has had a tumultuous relationship. “Oheka is an imposing, magnificent facility. I liken going to Oheka Castle to in some respects going into the Oval Office.”

In this world, it’s not a wedding involving a pop star that catches the eye. It’s weddings of people like Steven Schlesinger.

Schlesinger, then counsel to the Nassau Democratic Party, married Caryn Fink, a law clerk, there in March 2014, filling the grand ballroom, restaurant and bar.

Assemb. Phil Ramos and his wife, Angela, held their wedding reception in the Terrace Room in 2015, documenting the event in an elaborate video.

Chuck Ribando, former Nassau County Executive Edward Mangano’s deputy for public safety, held his daughter’s wedding at Oheka when he was chief investigator for then-Nassau District Attorney Kathleen Rice.

For at least some insiders, the payment terms are different from what Melius normally charges. In an August 2014 interview, he said he routinely gives discounts to law enforcement personnel and personal friends, including those in politics. He didn’t offer examples. But Schlesinger didn’t pay for his wedding until five months later, a day after a Newsday reporter made inquiries about judicial assignments he and other associates of Melius had received. He produced a $75,000 check as proof of payment.

Financial interactions involving Melius and Schlesinger drew the interest of the courts, where an examiner found later that there had been no invoices for the wedding at Oheka and that an internal worksheet listed no money due and contained the word “barter.”

The Friday cigar nights, at which a strong law enforcement contingent has mingled with the Island’s elite, have been held in the castle’s courtyards, according to several regular attendees. Mangano dropped in regularly with then-County Sheriff Michael Sposato often driving. Alfonse D’Amato, the former U.S. senator who remains politically involved, has also popped by occasionally.

Robert Hart, who headed the Long Island FBI office and has served as a deputy Nassau police commissioner, has attended, as has Malcolm Smith, once the Democratic leader of the State Senate who was convicted on corruption charges involving his would-be New York City mayoral campaign in 2013.

Sprinkled through many of the rooms have been several decades of fundraisers for such figures as state Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman, Mangano, Suffolk County Executive Steve Bellone, then-Suffolk Legis. Lou D’Amaro, and Steve Levy, then-Suffolk County executive. In an interview, Melius said he had hosted in-kind fundraisers for Levy and D’Amaro, meaning that he donated the cost of the events to their campaigns.

Many of those closest to Melius have often been invited to the library for brandy and cigars. State Independence Party leader Frank MacKay, who has posted Oheka photos on his Facebook page, has been one. Mangano has been another.

Far removed from the public tour, past the basement bakery and laundry, there’s what Melius calls the man cave, which remained unfinished as the rest of Oheka was reborn, with wooden planks leading to a wall lined with urinals. Melius has one rule for that room: No women allowed — even politicians he’s trying to cultivate.

In a March 2012 email to Rice, then the Nassau district attorney, in which he passed along the resume of a good friend’s son, Melius wrote: “Hi, Kathleen, I really enjoyed the other night, lots of laughs. Sorry I couldn’t bring you to the man cave, wink wink — but rules are rules.” That email and other emails provided by the district attorney’s office show no response from Rice, and her office said she made none.

The Chaplin Room, where the fuchsia walls are lined with photos and posters of the Little Tramp, is another special place. Although the public can rent it for parties, it outranks even the man cave as a home of political muscle-flexing. Beyond the election night gatherings that have drawn former Congressmen Steve Israel and Gary Ackerman, and other top elected officials, the truly special event is the running poker game, where the regulars have included D’Amato, Schlesinger and Dennis Lemke, a prominent criminal defense attorney, others who have attended said.

The Chaplin Room also has been used by the Independence Party to screen candidates for office, according to Jacobs, the Nassau Democratic chief. Oheka is the unofficial headquarters of the party, which has drawn enough votes to sway judicial elections in Suffolk and provides a platform for MacKay to negotiate complicated cross-endorsements that can assure a candidate’s victory.

“If you’re the Independence Party, your home court is an advantage,” Jacobs said.

Melius has been listed as the party’s chief adviser, and he has paid MacKay, the party’s statewide and Suffolk County chief, as a public relations executive at Oheka. In 2016, MacKay earned between $20,000 and $50,000 according to state filings that require party leaders to list outside income in broad ranges. In previous years, he made between $100,000 and $150,000 annually. Oheka also employs Richard Bellando, the party’s Nassau head and Melius’ former son-in-law.

A dining room lined with silk murals has hosted what MacKay calls “power networking luncheons,” where he and Melius have brought together Broadway producers, local politicians, law clerks and judges.

Judges are prohibited from politicking, so casual gatherings with party leaders offer an opportunity to get known. The connections can be useful.

Nowhere is that more evident than in the history of Thomas Whelan, who, while Babylon Town attorney in 1988, drove across the median on the Southern State Parkway and hit an oncoming car, seriously injuring a Commack man.

Whelan was charged with second-degree assault, vehicular assault and driving while intoxicated. He ultimately was convicted of three misdemeanors and a violation and sentenced to probation for 3 years. He was not reappointed by the town when his term expired.

It was a setback that could derail a career.

But in 2000, Whelan, who is godfather to MacKay’s daughter, saw his career resurrected after MacKay constructed a complex cross-endorsement deal on his behalf. By agreeing to Independence Party backing for Democratic candidates, MacKay persuaded the Democrats to back Whelan for a Suffolk Supreme Court judgeship, party leaders told Newsday at the time. He also secured Conservative and Working Families lines.

With those cross-endorsements, Whelan won with the highest vote in the 10th Judicial District.

By 2011, his career in full bloom, Whelan was assigned to one of Suffolk’s three commercial courts, where business litigation and foreclosures provide opportunities for coveted judicial appointments for lawyers and property managers to oversee troubled assets.

Whelan was also a welcome guest at Oheka and attended the castle’s posh Super Bowl parties, Melius recalled in an interview.

In an interview with Newsday editors last year, Melius readily acknowledged Oheka’s popularity, and his. “Everybody comes to me,” he said. “You know why? I deliver if I can. If I can’t, I tell you. I don’t pay anybody off.”

Power in action

Oheka’s power hubs intersect freely, particularly over arcane opportunities that only political insiders might recognize.

One involved Oheka itself, already the beneficiary of many decisions by the Huntington Town Board that allowed and expanded commercial activity in a residential neighborhood. Many board members frequented the castle, had become Melius’ friends and received generous campaign contributions from him. They credited their decisions with restoring an architectural gem.

But those decisions paled in potential impact to one they made in 2012 permitting construction of 191 condos on the property projected to sell for between $1 million and $5 million. The potential value created by their vote could run into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Cuthbertson, a Democratic board member whom other guests recall seeing at annual garden parties at Oheka and who received more than $30,000 in contributions from Melius over the years, opened the way in 2009. He sponsored a resolution establishing cluster zoning of golf courses — including the one next to Oheka. Such zoning allows a developer to build more units than normally permitted in one area of the cluster in exchange for preserving open space in another.

Cuthbertson then sponsored the critical 2012 zoning change to allow 191 condominium units on the property, which passed unanimously. Oheka Castle is 109,000 square feet. The proposed condo complex would be 393,427 square feet.

At the time, Cuthbertson was engaged with Melius in another lucrative public realm. They and Melius’ daughter, Kelly Melius-DiPreta, were involved in two court-appointed receiverships that earned the three a total of $284,000 in fees and expenses.

Cuthbertson did not disclose those ties at the time of the town board’s vote. He said this was because his was a “parallel” relationship in which a judge appointed him and the Meliuses separately, although he did acknowledge that he had recommended Melius-DiPreta for her assignment. The town ethics board, whose members are appointed by the town board, later found that he committed no “technical ethical violation,” but said Cuthbertson should disclose such appointments in the future.

The judge in both receiverships was Whelan.

When he was assigned the case of a foreclosed medical building in Islandia in 2008, Whelan named Cuthbertson to the role of receiver, the person who manages a building’s finances and overall operation.

Whelan chose Melius to run the building day-to-day as property manager. He was not on an approved list of professionals established by the courts after repeated scandals involving judicial appointments of donors and cronies.

Because Melius was not on the list, court rules required Whelan to write a finding “of good cause” to appoint him. In similar instances, other judges have cited a person’s particular expertise with an unusual type of property, like a horse farm. The Islandia property is an office building.

Whelan declared that Melius had “the appropriate ethical character” for the post.

Whelan’s lawyer, Clifford Robert of Uniondale, said in a statement that the judge, who was subsequently transferred out of the commercial part, had “proudly upheld the highest standards of both the practice of law and of the judiciary.”

Cuthbertson, who was paid $101,594 for his role in the Islandia building, said in an interview that he had recommended Melius’ daughter as manager for a subsequent receivership, because he thought she was well qualified.

Altogether, Melius and friends and allies collected more than $750,000 in fees from four receiverships. Among those allies were his former son-in-law, Bellando; his lawyer, Ronald Rosenberg, and Schlesinger, court records show.

Coveted appointment

Schlesinger, meanwhile, has reaped rewards in another judicial sphere and shared them with a charity created by Melius, his Oheka poker pal.

He was appointed by the Nassau County Surrogate’s Court to manage a foundation created by Shirley Gitenstein of Atlantic Beach after her death in 2007. The Kermit Gitenstein Foundation, with $11.4 million in assets, financed Jewish causes and health care.

This kind of appointment is coveted by politically connected lawyers because foundations created by wealthy individuals who die without heirs need to be managed and their funds distributed. The fees for carrying out these functions can be substantial. Records show Schlesinger earned more than $100,000.

Schlesinger gave $250,000 of the Gitenstein money to the Elena Melius Foundation, named for Melius’ mother. The donation came two days before Schlesinger’s wedding. He also provided $50,000 of the Gitenstein Foundation’s money to a charity started by another Oheka poker pal, D’Amato, who spent the money on a water park that was built in his hometown, Island Park.

In May 2016, the newly elected Nassau Surrogate’s Court Judge Margaret C. Reilly issued a scathing ruling and removed Schlesinger, calling him “unfit” because he had engaged in potential self-dealing, exceeded his authority as receiver, and had failed to comply with court orders.

Joseph W. Ryan Jr., appointed by the court to examine the case, found that Schlesinger had allowed Melius to direct where thousands of dollars in grants from the Gitenstein Foundation should go. Reilly said that was a conflict of interest, citing an email to Melius from Schlesinger’s legal assistant that asked him “to list the organizations Gary Melius decided on and the amounts requested . . . I don’t want to miss any.”

Both the state attorney general’s office and the Eastern District of the U.S. attorney’s office investigated the transactions. A spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office declined to comment.

In a court settlement related to the state attorney general’s office inquiry, Schlesinger agreed to stop taking commissions from the foundation and pay back $150,000 he’d earned as receiver. He was forbidden to serve on a nonprofit or charity for five years.

Schlesinger declined to be interviewed for this story. He said in a statement that he had made “no admission of wrongdoing.” His spokesman, Gary Lewi, has said Schlesinger “discharged his fiduciary duty appropriately.”

Melius has strongly denied any wrongdoing.

Partnership deteriorates

Other deals involving Melius imploded because of friction between him and his partners. One involved an engineer, John Ruocco, who created a company, Interceptor Ignition Interlocks, that produced a device to prevent people convicted of drunken driving from starting their cars if inebriated.

To get an edge on the competition in the market, court records show, he gave Melius nearly 3 million shares of stock in return for help in getting Nassau and Suffolk to enact regulations that mandated use of technology employed by his company.

Melius reached out to his contacts, including D’Amaro, the Suffolk legislator for whom he sponsored an Oheka fundraiser, and the Mangano administration. Both counties approved regulations that favored the company’s technology, and Interceptor’s market share soared.

Interceptor’s market share went from 7 percent to 54 percent in Nassau. In Suffolk, the company’s market share increased from 13 percent to 22 percent.

But the partnership deteriorated. Melius sued Ruocco, and, with the approval of both sides, the case was decided by Whelan. He issued a ruling that gave Melius control of the company’s stock.

A New York State appeals court eventually reversed Whelan’s decision, saying that he had failed to hold a jury trial, as Ruocco had requested, and thus should not have granted summary judgment in favor of Melius. Ruocco has said he hopes he can revive the company.

Prior to the appeals court decision in December 2016, Melius had struggled to put Interceptor completely under his control.

At the first board meeting after Whelan’s decision, on Feb. 21, 2014, Melius added one ally to the board but was unable to gain a majority.

Three days later, Melius was shot.

A shooting unfolds

The grainy video lasts all of 49 seconds. It starts with Gary Melius in a dark winter jacket striding on a diagonal from the lower right of the frame across the rear parking lot of Oheka Castle. After about 12 seconds, he reaches the driver’s side of his black Mercedes and lowers himself in.

As he does, a dark sedan leaves the lot. It circles behind him, slows briefly and pulls out of the frame.

Eighteen seconds later, a tall man wearing a winter jacket becomes visible getting out of an SUV at the far left of the frame, hunching a bit and moving quickly as he snakes among three cars to reach the driver’s side of the Mercedes. Only the back of his head is visible as he fires the shot that strikes Melius in the left temple. He remains there two and a half seconds.

The gunman then hustles away, crouching at two points looking toward his hands and then back at the car, as a worker emerges from behind a building at the parking lot’s edge. Next, the shooter vanishes, about 13 seconds after he first appeared.

He remains unidentified to this day.

After the shooting, detectives sought the names of Melius’ adversaries, trying to determine who might have a motive for doing him harm.

They knocked on a lot of doors, including that of Ruocco, whose former lawyer said he is not a suspect in the case.

“Simply put, there are so many suspects,” a law enforcement official who has been briefed on the investigation said in 2017.

Another law enforcement source with direct knowledge of the case said it quickly became clear that Melius “was connected to everybody” and that the list of potential suspects grew to more than 60 people.

Russian mobsters were caught on tape chuckling about the shooting, according to a law enforcement source, but that lead went nowhere. In the interview with Newsday editors, Melius voiced suspicions about a restaurateur, but nothing has surfaced about that, either.

Melius’ friends and family offered a $100,000 reward and hired a billboard truck, which was briefly parked in a Newsday lot to announce it.

But an official involved in the case said that when questioned, Melius had given leads to detectives that did not prove fruitful.

Melius said he has cooperated fully with police. But he may have hinted at tensions with law enforcement authorities’ handling of the investigation in a comment to Newsday reporters several months after the shooting about the prosecutor heading the investigation, Nancy Clifford. “If I don’t like her, I won’t tell you,” he said.

He blamed the police department and Suffolk District Attorney Thomas Spota for failing to solve the shooting in the interview with Newsday editors. Spota was indicted last year for allegedly obstructing a federal investigation into the beating of a prisoner by former Suffolk Police Chief James Burke and its cover-up.

“I think the PD screwed up, Tommy Spota screwed up by not putting out the picture of that car,” Melius said, referring to the fact that the Suffolk Police Department released the video two years after the shooting. A spokesman for Spota said last year that it is standard procedure not to release such videos in an ongoing investigation.

The police department declined to respond to requests for comment.

Burke, the police chief who headed the shooting investigation, went to federal prison in 2017 for his assault of a suspect in 2012. Spota, Burke’s longtime mentor, and one of his chief aides were indicted in October 2017, accused of being involved in covering up the assault. Spota retired in November, maintaining his innocence.

The fallout

Since the shooting, FBI agents have carted away boxes of material from Oheka. Melius said the agents had found nothing incriminating. “The FBI came to me and they wanted my stuff and I gave them 180 boxes of stuff,” he said. “And you know how many I had my lawyer look at? None. I have nothing to hide. I gave them everything.”

Melius said his life has fallen apart, as well. He can’t drive because he suffers seizures, and he can no longer enjoy a bourbon or a cigar, he told Newsday editors.

His wry conclusion: “I will never do that again, getting shot in the head.”

Oheka is also hurting. It had a net operating income of $2.38 million in 2014, according to Bloomberg’s financial data. That fell to $1.82 million in 2015 and $742,577 a year later.

In July 2015, Melius’ mortgage company, LNR Property LLC of Miami Beach, noted that Oheka required “substantive repairs” and needed a monthly budget of $72,455 for maintenance.

In December 2015, he stopped making mortgage payments, according to Trepp LLC, a Manhattan property data company. He was hit with a foreclosure lawsuit that continues. As of January, he owed $26 million on Oheka’s two mortgages.

“I am not sitting up there counting bills and money,” he said. “I don’t have it. I’m fighting for my life.”

The long shadow Oheka casts over local politics seems to have grown a little shorter, too. Meetings with party leaders, other than MacKay, have diminished, by many accounts.

Facing tough odds

At times like these, the cozy network of Long Island politics has been Melius’ reliable safety net.

In mid-August, as the battered Mangano administration faced its last months in office, it placed an item on the Nassau Legislature’s agenda that would allow Melius to connect Oheka, which is close to the Nassau-Suffolk border, to Nassau’s sewage system — quite literally the last link needed to fully realize a vision of Oheka he has harbored since 1984.

The hookup would handle a projected 156,000 gallons of wastewater a day from the condos Melius won approval to build in 2012. The proposed agreement called for Melius to pay $425,000 to connect to the Nassau system, as well as $23,000 for a sewer permit.

For a proposed development across the street from Oheka, the figures are strikingly different. It would pay more than twice as much for fewer than half the units and less than a third of the projected wastewater.

When news of the proposal emerged, the item was yanked from the agenda and, in an anti-corruption-themed campaign season, both candidates to succeed Mangano immediately voiced skepticism.

Melius told a reporter in October that he would not comment because the Newsday news article on the sewer hookup had “cost me millions.”

A new leader has taken the helm in Nassau, with Laura Curran, a Democrat, as the new county executive. In Suffolk, upstart Democrat Timothy Sini has taken over the district attorney’s job. They have promised to restore integrity to government.

But in an election season imbued with the drumbeat of reform, there were quieter lessons about the resilience of machine politics. In Suffolk, the Democrat, Errol Toulon Jr., defeated a Republican in the county sheriff’s race with Conservative and Independence Party support, which provided the margin of victory.

Sini won after a similar cross-endorsement deal. Curran celebrated her victory at a news conference in which she stood next to Nassau’s Democratic leader, Jacobs.

Melius, now 73, with many friends fading from the scene or already gone but others holding fast, finds himself again in a place both precarious and familiar — facing seemingly tough odds on the playing field of Long Island politics.

The question is whether the rules of the game have changed, or whether they easily can be.

Intro:

Intro: Video:

Video: Chapter 1:

Chapter 1: Chapter 2:

Chapter 2: Chapter 3:

Chapter 3: Chapter 4:

Chapter 4: Chapter 5:

Chapter 5: Chapter 6:

Chapter 6: Chapter 7:

Chapter 7: