A multimillion-dollar taxpayer bailout

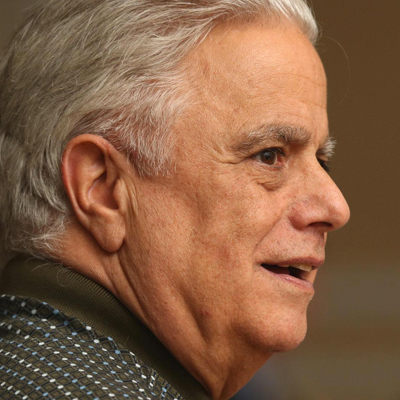

Gary Melius navigates a way out of the Water Works property

Freeport Village Attorney Howard Colton went to police in July 2009 with a startling accusation: Gary Melius was verbally threatening him and he feared for his safety and that of his family.

At the time, Melius was trying to resolve a long-standing legal dispute with the village over his Brooklyn Water Works property, a 4-acre site that he had tried unsuccessfully to develop for two decades and wanted to sell.

Colton told Freeport’s police chief by email that Melius was “pressuring” him to force a settlement and claimed to have incriminating recordings and the clout to get him indicted. Melius was using the Nassau County district attorney’s office and its chief investigator, Chuck Ribando, as “his private police force,” Colton wrote.

By the time Colton leveled his charge, Melius had remade Oheka Castle into a magnet that drew political, business and law enforcement elites from across Long Island and catapulted himself to a new level of influence. Melius was now more than a man with influential friends; he was a power broker.

To unburden himself of the money-losing Water Works, Melius worked the levers of electoral politics. In Freeport, he put his political weight and pocketbook behind the successful mayoral campaign of Andrew Hardwick, a five-time loser in previous election efforts. Then, after donating $15,000 to the re-election campaign of Democratic Nassau County Executive Thomas Suozzi, he pivoted to Republican Edward Mangano after his surprise 2009 victory over the incumbent. Melius made a $2,500 donation to the apparent victor before Suozzi even conceded in December.

Melius, Hardwick and an FBI wire

Melius estimated in a 2012 interview that Water Works had cost him $13 million over the years. At one point his tax and mortgage liabilities on Water Works exceeded $3 million. Moreover, village residents largely opposed his development plans as too large and intrusive for the neighborhood, and he’d failed to find a private buyer.

Melius looked to the Hardwick and Mangano administrations for help. They would come to Melius’ aid by spending a combined $11 million in taxpayer money, all of which went into the pocket of the castle owner or to his various creditors.

That figure includes a $3.5 million legal settlement that Hardwick spearheaded despite acknowledging the conflict in his personal relationship with Melius, a $900,000 tax refund from the village, a $500,000 settlement that county officials declined to discuss when it was reached, and $6.2 million that Nassau paid to purchase Water Works — an amount three times the county assessor’s estimated market value.

The Mangano administration justified the inflated price by saying that Melius had won valuable development approvals, when, in fact, the village had denied him a building permit.

Powerful figures using the public purse to satisfy private ends is not a new story in Nassau. But Melius’ maneuvers with Hardwick and Mangano stand out as a brazen display of political muscle.

Melius declined repeated interview requests for this story. In previous public statements, he described himself as a victim of unscrupulous village officials who had tried to “steal” the property from him.

“I just want to get out,” Melius told Newsday the year before Nassau bought Water Works. “I want to sell it.”

The multimillion-dollar taxpayer bailout that Melius secured shocked even veterans of Long Island business and politics.

Desmond Ryan, the retired longtime leader of the Association for a Better Long Island, a real estate trade group, said the county’s purchase of Water Works was a “deal to die for” that left him and others in the industry “stunned.”

“You buy this piece of property, you don’t get what you want and now you want to unload it back on the county?” Ryan said. “What, are you kidding me?”

A frustrating money-loser

In the 19th century, the City of Brooklyn undertook a massive public works project to supply its residents with water from Long Island.

The project’s largest pumping station — a Romanesque Revival redbrick structure with castle-like towers and huge arching windows — was built near Freeport’s Milburn Creek. Throughout the 20th century, the station, known as Brooklyn Water Works, was used less and less and was shut down in the 1970s.

Melius saw opportunity in the station’s ruins in 1986 when he purchased the then-county-owned property for $1.4 million. But Water Works quickly proved a frustrating money-loser. Melius feuded with village mayors and residents over development proposals and saw deal after deal dissolve into lawsuits as the once-grand structure slowly collapsed, becoming a graffiti-covered eyesore.

Melius came to bemoan the purchase and engaged in a long battle with then-Mayor William Glacken over property tax payments. What Melius’ attorney dubbed a “business decision” for Water Works involved remaining delinquent on his village and county taxes, making good only when liens, which can be purchased by private investors, put him at risk of losing the property, according to a lawsuit.

Melius’ ownership was briefly in question after a group of private tax lien investors obtained deeds, but a judge in 2006 declared Melius the rightful owner, saying he’d not been properly notified of deadlines he faced to pay the liens off.

Even so, Melius in 2008 sued the village, Glacken, other village officials and Nassau County, alleging a conspiracy to steal Water Works by secretly transferring the tax liens to the investors. Melius had first raised his allegations years before, and FBI investigators began questioning those involved in 2006, according to court records.

At a campaign event in early 2009, Glacken told village residents that Melius’ conspiracy lawsuit was an attempt “to extort money from you.” Melius sued Glacken for defamation and lost the case at the state appellate level.

Hardwick becomes mayor

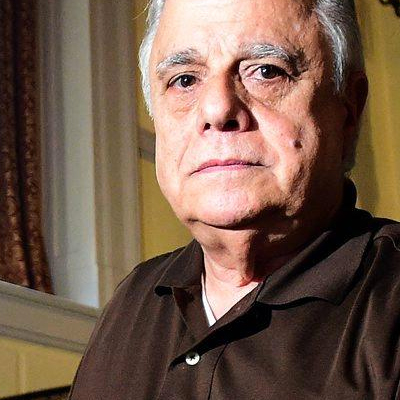

Melius needed a friendlier administration in Freeport. And Hardwick, an aspiring politician with a pugnacious style, needed help if he was ever to win an election.

A captain in Freeport’s volunteer fire department and former assistant to two Freeport mayors, Hardwick lost a race for state Assembly in 1994 as a Republican; failed to make the ballot in 1995 and 1997 after holding himself out as a potential candidate for Nassau Legislature; then lost a race for village trustee in 1999 and unsuccessfully challenged Glacken for mayor in 2005.

He filed to challenge Glacken again in 2009 — this time with Melius as an ally.

Melius asked Nassau Democratic leader Jay Jacobs to back Hardwick. Jacobs recalls being reluctant. Glacken, however, was a Republican. Melius had given the Nassau Democratic Party nearly $40,000 in the previous three years. Jacobs and the party gave Hardwick $3,580.

Two weeks before Election Day, Hardwick received a combined $2,997 in donations from Melius’ wife, daughter and former son-in-law, Richard Bellando, records show. The donations plus Jacobs’ money totaled nearly a third of what Hardwick raised.

On Election Day, workers from Oheka Castle were out campaigning for Hardwick, according to current Mayor Robert Kennedy, who ran on a slate with Hardwick for village trustee. Hardwick won by 328 votes of 5,842 cast.

Hardwick’s combative streak and sometimes curious actions during his single mayoral term would cause controversy. Here’s a sampling:

When sworn in, he had a band play “Hail to the Chief,” which is used to announce the president of the United States. During his first weeks in office he had the village hire a private security team to guard him at a cost of nearly $10,000, citing unspecified threats. He and an aide toured China on a “trade trip” paid for by the village. He used the village’s automated phone system to contact residents with a recorded call that attacked a political opponent. He apologized after hosting the vice president of El Salvador, who had participated in anti-American protests after 9/11. And in his unsuccessful re-election effort, he sent out a mailer falsely claiming that he had the personal endorsement of then-President Barack Obama.

As mayor, Hardwick, a regular at Oheka Castle parties that drew cops and politicians, worked to resolve Melius’ Water Works woes and put millions of dollars in the pockets of the castle owner and a close Melius ally.

Three months after Hardwick’s swearing-in, the village retained Steven Schlesinger’s law firm as an outside counsel. A Melius poker pal whose 2014 wedding was held at Oheka, Schlesinger was then the Nassau Democratic Party attorney. Records show that his firm collected $1.1 million from cases it was assigned during Hardwick’s single term.

Schlesinger and Hardwick declined to be interviewed.

Allegations of intimidation

Freeport Village Attorney Colton charged that within weeks of Hardwick taking office in April 2009, Melius’ intimidation campaign began, according to internal records and emails that Newsday obtained.

Melius first unnerved Colton by instructing him to report to the Nassau district attorney’s office, according to an email the attorney sent in July of that year to then-village Police Chief Michael Woodward. Colton wrote that Melius told him he was “personal friends” with the office’s chief investigator, Chuck Ribando, and that an indictment “is coming” of Colton’s predecessor, Joe Edwards.

“Melius informed me that I should go in on my own before, ‘they come and get you,’ ” Colton wrote to the police chief.

Edwards, also a Melius adversary over Water Works, was never indicted. He did not return calls for comment.

Ribando was a retired 20-year NYPD veteran when he joined the Nassau district attorney’s office in 2006 to lead the investigations division. He was a regular at Oheka, according to Melius and castle guests in law enforcement. When a wedding reception for Ribando’s daughter was held at Oheka in 2012, an overnight affair that saw all the castle’s hotel rooms booked, Melius said he charged a discount. In a 2014 interview, Melius said that he had been unable to book an event for that date, and that under such circumstances, he typically lowers his prices.

Melius kept calling in the summer of 2009, according to Colton, and on July 22 Colton filed a formal complaint with village police. Melius had phoned him that day and asked for a “status report” on settlement talks, he wrote. When Colton told him that no report was ready, according to the complaint, Melius exploded. “You don’t know who you are [expletive] with,” Colton said Melius yelled. “I’m coming after you. I’m going to get you. I’m going to get you indicted and the rest of you [expletive].”

Many people who have interacted with Melius over the years, including business adversaries, have experienced this boorish and bullying side.

“If you punch me in the nose, I am going to punch you back,” Melius told Newsday editors in April 2017.

According to Det. Sgt. Raymond Horton’s summary of what Colton told him, the village attorney brought Melius’ alleged tirade to Hardwick’s attention. Colton “reported that Mayor Hardwick had told him that Gary Melius has an anger management problem and to let cooler heads prevail,” the sergeant wrote.

In his complaint, Colton requested that no further action be taken in the matter, but then followed up with an email to Chief Woodward that detailed these events:

On July 28, 2009, after he said he and Ribando had exchanged telephone calls, Colton wrote that the two met and Ribando questioned him about the alleged tax lien scheme that Melius argued was designed to defraud him of Water Works. Colton said he told Ribando he had little knowledge of the matter and was not involved.

Colton told the chief: “Melius has made several veiled threats at me in the hopes of pressuring me to force a settlement of the Water Works civil litigation,” he wrote. “Melius has informed others that he has tape recordings of me, but when asked to produce them, he cannot. . . . It is obvious that this is being used as a pressure tactic.”

The following day, July 29, Colton met with Hardwick and Melius at the Grand Lux Café in Garden City to talk about the settlement, according to the email. During the meeting, Colton wrote that Melius took a call from a man named “Chuck” who “clearly” was Ribando.

“I have concerns that the County DA’s Office has been corrupted by Melius and he is using them as his private police force,” Colton wrote to Woodward.

The district attorney’s office said that it never received a complaint from Colton or Freeport police about Melius’ conduct and his ties to Ribando, who declined to be interviewed for this story. However, another public official notified the district attorney’s office of Colton’s concerns, according to emails Newsday reviewed.

At the time Colton lodged his complaint, Kathleen Rice, now a congresswoman, was Nassau district attorney. Her spokesman Coleman Lamb said in an email that any suggestion Melius had corrupted the office was “ludicrous.” Lamb added that he could not “speak for Chuck Ribando, but I can certainly say that he did not run the DA’s Office. He had bosses, and he couldn’t indict anyone.”

A month after Colton’s July 29 meeting at the Grand Lux Café, and after years of antagonism, it became clear that Freeport’s posture toward Melius had undergone a striking reversal, as would the village attorney’s. The village agreed to settle its tax dispute with Melius by reducing the assessments levied on Water Works over the prior decade and cutting him a $900,000 refund check. Six weeks after the meeting, the village settled Melius’ conspiracy lawsuit for $3.5 million.

Hardwick pushed for the settlement, Mayor Kennedy said. Attorneys close to Hardwick presented cost estimates justifying the move, Kennedy recalled, suggesting that if the village lost, it would have to pay attorney fees for both sides, which could total at least $4 million on top of any judgment for Melius.

When the settlement was voted on, two trustees abstained. Hardwick and his two running mates, including Kennedy, voted for the deal.

In a written disclosure filed with the village, Hardwick acknowledged that he had a potential conflict of interest. Melius was “personally known to me,” he wrote, and as a result he would “prefer to abstain.” But without his vote, the settlement would fail, Hardwick said, exposing the village to the risk of “burdensome taxes or, in the worst case, a potential municipal bankruptcy.”

Glacken, the former mayor who is himself an attorney, said in an interview that the village had no liability and Melius no case. Glacken said Melius’ lawyers had not even deposed him or other defendants. The Hardwick administration “just rammed this thing through,” he said.

“If I had still been there, we would not have settled the case,” Glacken said. “We would not have given them a dime.”

A relationship thaws

By summer 2010, the relationship between Colton and Melius had undergone a remarkable change. No longer an adversary, Melius had become Colton’s regular host and the attorney began attending twice-monthly dinners at Oheka, according to a deposition he gave the following year.

In an unrelated case involving allegations of discrimination in the Freeport Police Department, Colton said in 2011 that Oheka dinner guests included lawmakers; county executives; state and county police officers; Robert Hart, the former head of Long Island’s FBI office and then-chief investigator for State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman; FBI agents; Rice; and Ribando.

In August 2010, Freeport put Colton’s father, a prominent rabbi, on its payroll as a $150-an-hour community liaison. Melius also hired Colton’s father as a consultant for Oheka Castle, according to the attorney’s deposition in the discrimination case.

A personal spokesman for Colton, John McDonald, initially said Colton declined to be interviewed because of a cooperation agreement with federal law enforcement. McDonald declined to say what the cooperation concerned then insisted after the fact that his comments had been off the record. Then, more than 48 hours after this story appeared online, he contacted Newsday to say that Colton is a witness for the FBI and that on advice of his counsel, Colton could not comment.

A bond with Mangano

As he won settlements from a more amenable Freeport, Melius also strengthened his bond with Mangano, then the incoming county executive. Mangano is awaiting trial on federal corruption charges in a case unrelated to Water Works.

Melius had supported Nassau Executive Suozzi’s re-election campaign, but nine days after the Nov. 3, 2009, election, amid a recount and mounting indications that Mangano had won an upset, Melius gave him a $2,500 donation. Suozzi conceded on Dec. 1.

During his first term, Melius, his wife, Pamela, and Bellando would donate a combined $17,900 to Mangano.

Today, Melius and Mangano are friends. They’ve traveled to New Jersey together to shop for dachshund puppies and to Las Vegas to gamble. Mangano has been a frequent guest at Oheka, appearing not only at regular private cigar parties, but also as an honored guest at large functions.

“I love him,” Melius has said of Mangano. “I think he’s the best political guy.”

With Mangano in office, Melius reaped rewards.

The day superstorm Sandy struck in 2012, for instance, the county awarded a $655,000 emergency debris cleanup contract to a Melius design and construction firm, ArchCon. The contract was among several awarded without bidding for debris removal. Available Nassau records show no previous county payments to ArchCon for debris cleanup or anything else. In an interview a few years later, Melius said, “Everything was done above board.”

In 2010, nine months into Mangano’s term, the county settled its portion of the Water Works lawsuit — in which Melius accused Nassau of having conspired with Glacken to wrest the property from him — for half a million dollars.

Asked at the time to explain the decision, the county declined.

Varying appraisals

Meanwhile, with the two settlements won, Melius renewed efforts to develop Water Works, proposing a complex that violated village zoning in multiple ways.

His plan called for a six-story, 140-unit apartment building and quickly drew fire. Under pressure from residents and environmentalists, Melius dropped the number of units to 121, a figure still almost 50 percent above what was allowed.

Dozens of angry residents attended village Landmarks Commission hearings. “I don’t need a gigantic monstrosity like that in my neighborhood,” one said. Another described the proposed plans as “scary . . . like looking at a big box store on Sunrise Highway.”

Only a handful of residents spoke in favor. Melius’ attorney wrote a letter threatening to sue the commission. “This is an attempt at intimidation!” one member of the board seethed in an email to her colleagues. But the final vote was 4 to 4, which under board rules kept the plan alive.

Before the development approval process could proceed, however, an alternative proposal from then-Nassau Legis. David Denenberg, who represented parts of Freeport, gained traction. Nassau should buy the property with money set aside to preserve undeveloped land, he argued.

Denenberg had suggested this before and had the site placed on the county’s list of potential acquisitions in 2006. It was situated along the South Shore, where open land is scarce, and bordered a nature preserve that Denenberg said he wanted to protect from development.

In 2006, the deal stalled over money. Two appraisers hired by Nassau pegged its value at $1.6 million and $2.7 million. An offer of $3 million was discussed, Denenberg said, but it wasn’t enough for Melius. In a court filing a few years later he said that he had once had a deal to sell the property for $8.5 million, but that it fell apart.

In 2011, the Mangano administration turned its attention to buying the property for open space and ordered two new appraisals.

By then, Long Island property values had crashed under the weight of a historic economic slump. Nonetheless, the appraisals valued the property at $6.3 million and $6.9 million — more than double the higher estimate from five years earlier.

During the same time period, the median value of condos and co-ops in Freeport had dropped 24 percent, from $420,000 to $318,000, according to the real estate data firm Zillow. Countywide, the decline was 21 percent.

Neither the appraiser who arrived at the $6.3 million figure nor the appraiser who produced the $6.9 million figure responded to multiple interview requests.

In April 2012, when the county assessor’s office last estimated market value for the property was $2.1 million, the Mangano administration and Melius drew up a sale contract for $6.2 million.

Explaining the price increase to county legislators the following month, the acting director of the Nassau Office of Real Estate Services, Michael Kelly, said that “time has gone on” and that Melius had obtained additional approvals to develop the property, “which, of course, raises the value.”

Both sets of appraisals assumed the owner would turn the property into a large residential complex with 121 units. Melius didn’t have approval to build any units, however, and under Freeport’s density rules the complex he proposed could contain at most 78.

Freeport’s superintendent of buildings had repeatedly rejected Melius’ permit applications in 2011, noting the many ways his plans didn’t comply with Freeport law.

The proposed apartment building didn’t provide enough parking, the superintendent wrote; it would take up too much of the parcel; and buildings taller than five stories were illegal.

“We’re getting a phenomenal deal,” Kelly, who did not return calls seeking comment, told county legislators. They approved the sale unanimously two weeks later. Two days after the vote, Melius’ wife, Pamela, donated $3,500 to Mangano.

The Nassau Interim Finance Authority, which monitors the county’s spending, was less sure the deal made sense. Its board voted 2 to 2 — a tie that let the sale proceed. However, even the two members who voted in favor questioned the price.

“There’s a lot not to like about this transaction,” said one of them, Chris Wright, “whether it’s the political motivation, the timing or the value.”

Nonetheless, Wright said, the use of long-term debt to finance the purchase was sensible, as was using money dedicated for open-space preservation.

The deal gets done

In September 2012, Nassau paid $6.2 million for Water Works. Of that, $3.2 million went to Melius and $2.6 million to his mortgage lenders. Another $400,000 covered taxes owed on the property. For Melius, the burden was lifted.

Twenty-one days after legislators voted for the sale, Melius’ wife made a $1,500 contribution to Denenberg. In the five years before the Water Works vote, Melius had given him $1,950; in the year after, Melius and his wife donated an additional $1,800.

In an interview, Denenberg, an attorney disbarred in 2015 after pleading guilty to stealing $2 million from a client, defended the purchase, calling it an important piece of property for Freeport residents.

Nonetheless, he acknowledged, the $6.2 million price tag seemed inflated.

“I had always thought that the price was less than half of that,” he said.

Intro:

Intro: Video:

Video: Chapter 1:

Chapter 1: Chapter 2:

Chapter 2: Chapter 3:

Chapter 3: Chapter 4:

Chapter 4: Chapter 5:

Chapter 5: Chapter 6:

Chapter 6: Chapter 7:

Chapter 7: