The rise of Oheka Castle

Gary Melius sells Oheka to a Japanese billionaire, then buys it back

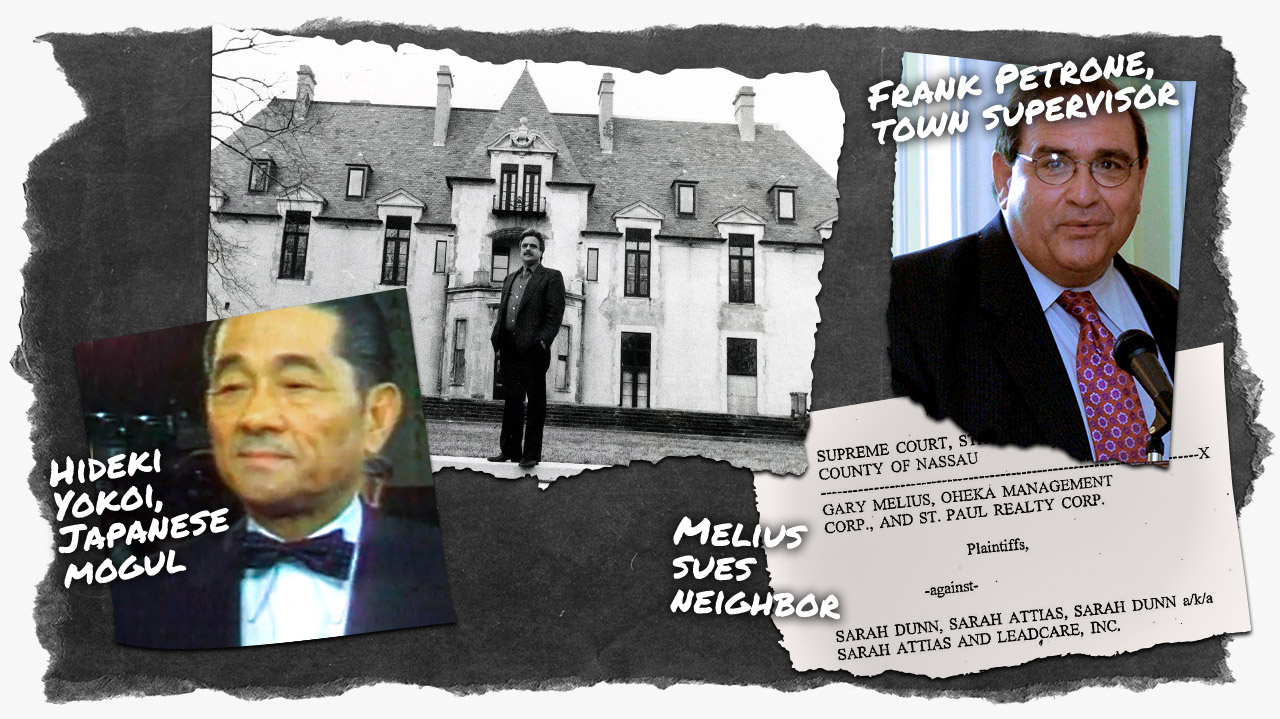

Christopher Okada still remembers the mysterious call his father, Naomi, a New York City real estate broker, received from Japan.

“All that my dad knew was that this client was extremely wealthy and he wanted castles,” Okada’s son, Christopher, recalled. “So my dad scouted the tristate area, and there’s not a lot of castles in the tristate area.”

But on the Gold Coast of Long Island there was Oheka Castle, and Gary Melius owned it.

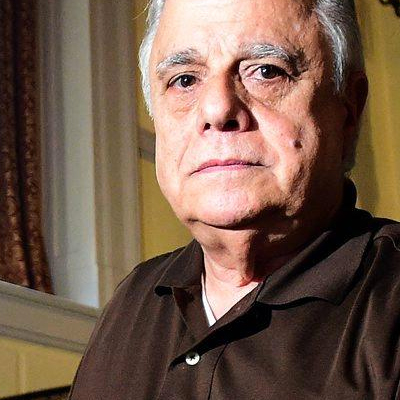

He had bought the abandoned mansion in 1984 for about $1.5 million, assuming ownership of what had been the grandest of Gold Coast estates and the second-largest residence in America. And he went to work, pouring money into a meticulous restoration he hoped would not only prove worthwhile on its own, but also would open the way for the lucrative development of 39 luxury condos.

His condo plan collapsed a few years later, though, along with the real estate and stock markets. His real estate empire was crumbling. He turned his attention to trying to transform the castle into a destination, a place for weddings, parties and other events.

Christopher Okada remembered that in 1988 his father called Melius on behalf of his new Japanese client.

It was the sort of moment people hope for when they buy lottery tickets. Melius would soon sell Oheka for a recorded price that was 15 times higher than what he bought it for — and get to live there as caretaker to boot.

The conversation led to a deal that eventually helped Melius emerge from multiple bankruptcies and business setbacks and enshrined him as a major player in Long Island’s politics and social life.

Remarkable in itself, the transformation provides a lens into the workings of Long Island politics and shows how somebody who had nurtured powerful people could overcome a formidable array of obstacles to get what he needed.

In Melius’ case, the obstacles included half a million dollars in unpaid property taxes, 17 building and fire code violations, vocal neighbors he had infuriated, business partners who ran afoul of the law, a decisive rejection by the Huntington Town Zoning Board of Appeals and two judicial orders against him, the last of which temporarily shut down Oheka.

A billionaire investor

Okada’s mysterious client turned out to be one of Japan’s most reviled figures.

Hideki Yokoi, an aging billionaire investor connected by the Japanese media with the vicious Yakuza crime syndicate, faced criminal negligence charges after a fire in 1982 ripped through a Tokyo hotel he owned where he hadn’t installed sprinklers. Thirty-three people died.

Worried about prison, Yokoi, who denied Yakuza links, wanted to get some of his assets out of Japan, and at one point his family even invested them in a purchase of the Empire State Building, with Donald Trump later joining as a partner. He began buying castles and other luxury residences in Europe and the United States, according to court testimony from a daughter, Kiiko Nakahara. She said that during the 1980s, she took photos of European châteaux and grand estates and sent them to Yokoi for inspection.

Through Okada, Yokoi bought Oheka for a recorded price of $22.5 million in 1988.

Then in 1993, Yokoi’s son-in-law, Jean-Paul Renoir, who was married to Nakahara, agreed to another deal, in which Melius leased back Oheka for $500,000 a year, records show, which apparently covered property taxes, maintenance and other operating expenses.

Violating zoning codes

Oheka was zoned residential, ensconced in an exclusive neighborhood near Cold Spring Harbor. Beginning in the early 1990s, Melius defied the zoning and began promoting the castle for weddings and catered events. He hosted private dinners and parties. He used Oheka to impress prospective business partners. He hosted profit-making events like wedding celebrations, a $300-a-seat Debbie Gibson concert and even flea markets.

He did this without town permits, a working sprinkler system or fire extinguishers, according to Huntington records.

A day after a 1994 “gala evening of tribute” for Frank Grimes, then the Huntington Democratic Party leader, a fire inspector warned Melius in writing to stop using Oheka as “a place of public assembly” until he obtained the required license.

Joseph Cassella, who was then Huntington’s chief fire marshal, said in an affidavit that “a potential catastrophe was barely averted” when children at a bar mitzvah in 1995 were led into a darkened basement for a “Halloween experience.” The basement was decorated with combustible materials that caught fire, then were extinguished, Cassella said.

Between 1994 and 1996, inspectors repeatedly found Melius violating zoning restrictions and codes. Records reveal at least 17 citations for illegal wedding receptions, blocked hallways, deadbolts on exit doors, plywood doors where fireproofing was required, combustible debris and unauthorized tree cutting.

Lawrence Cregan, who was then town attorney, said he felt compelled to take action against Oheka.

“You have to stand for something in this world,” he said in a recent interview. “I have to be able to sleep at night. I have to be able to face my children should something ever come to question. I prefer to do what’s right.”

On Oct. 24, 1995, the Huntington Town Board voted to obtain a court order compelling Melius to remedy “dangerous conditions.”

Three days later, a judge granted an injunction requiring Melius to comply with fire codes. He was ordered to install emergency lighting and fire stops, rehang fire doors, clear hallways and remove combustible debris. Oheka lacked an operable sprinkler system and so Melius was ordered to install one. He settled the case by agreeing to do so.

Tensions were high with neighbors, too, who complained that speakers boomed music so loud their homes rattled. “We do not welcome another summer of lounge lizard music,” a neighbor, Sarah Dunn, wrote to the town in 1996, adding, “the more sleep I lose, the nastier I get.”

On top of this, Melius had fallen far behind on property taxes. By 1997, he owed $668,557, tax records show.

Melius argued in a deposition that he was in compliance with zoning regulations because he believed there were no restrictions on renting out the residence. The weddings, parties and other events were legal, he insisted, because they were private affairs, including the flea markets and Debbie Gibson concert.

For a private residence, though, Oheka was quite busy. During a six-month stretch in 1996, 39 weddings and a Sweet 16 party were scheduled, according to documents filed with the court.

The town went back to court; in July 1996, another judge, Suffolk Supreme Court Justice Howard Berler, found Melius had failed to uphold the earlier “unambiguous” court order. He ordered Oheka shut down until Melius met fire safety codes.

In December 1996, a half-year after the court order shutting down Oheka, Melius asked the Huntington Town Zoning Board of Appeals for a variance allowing the castle to be used commercially. He was turned down.

A new offensive

For owners hoping to win a zoning change, such a record of noncompliance would prove daunting. And Oheka’s circumstances were worse than they looked on the surface.

Melius was leasing the castle, but its ownership was murky and being contested. The castle was held either by Yokoi, the billionaire who served 2 years in a Japanese prison in the mid-1990s after the calamitous Tokyo hotel fire, or by his daughter, Nakahara, and her husband, Renoir, who had each done prison time during a family battle over Yokoi’s vast real estate holdings in Europe and the United States.

After Yokoi filed fraud charges against them in France, Nakahara spent a year in a French jail and Renoir spent more than 2 years in American prisons fighting extradition. The French authorities eventually dropped the extradition request, freeing Renoir — but not before Nakahara was accused by irate mayors in nine French towns of having stripped the castles her father had purchased of marble, statues, tapestries and nearly anything else of value. She was not charged by French authorities.

But in Huntington, Melius was playing on his home field and determined to find a way to operate Oheka commercially. What emerged was something new for Melius and far more sophisticated.

He fashioned a new offensive that early on included a flash of his traditional aggressiveness — a $10 million libel suit against his most persistent and quotable critic, his neighbor Sarah Dunn, an environmental consultant who filed noise complaints and spoke up at council meetings.

But he also paid special attention to his public image, which was honed to portray him as a committed preservationist intent on reclaiming a piece of Long Island history for the public’s benefit. Town board members who had long benefited from his political contributions and friendship would eventually allow commercial use, despite his history of violating town codes and judicial orders, and not paying his taxes.

Political lifeline to Huntington

Despite his financial struggles in the ’90s, Melius still managed to finance his political lifeline, particularly in Huntington. Considered broadly, between 1985 and 2000, Melius, his family, his companies and employees contributed at least $180,515 to federal, state and local political campaigns, according to campaign finance records. They are incomplete because local campaign records are available only as far back as 2006 and state and federal records go back only to the 1980s.

Campaign donations by Melius, family and his companies

A Gannett Suburban Newspapers survey of corporate contributors that exceeded legal limits found that in 1995, the state’s worst offender was Melius’ Oheka Management Corp., which had exceeded the limits by $21,265.

“Who the hell knew anything about this?” Melius said in a Newsday interview at the time. “I called four lawyers, and nobody knew this, so how the heck am I supposed to know? Stupidity they could charge me with. I plead guilty.”

Existing records and news articles revealed that over the years Melius, his family members, companies and employees have contributed a substantial part of their combined campaign donations through 2017 — at least $214,067 — to political committees and elected officials from Huntington.

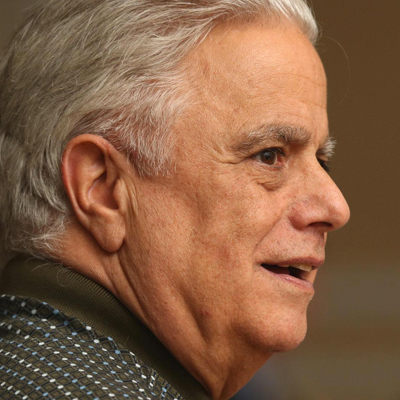

In the last dozen years, Melius, his former son-in-law and his companies gave $33,742 to Frank Petrone, according to records. Melius also hosted parties at Oheka for Petrone, who was the Huntington supervisor for 24 years. He did not seek a seventh term last year.

Melius became Huntington Councilman Mark Cuthbertson’s biggest donor, giving him at least $31,300, based on campaign records.

Steve Israel, a Huntington councilman in 1997 before his election to Congress, received at least $33,200 in donations from Melius and his family for his congressional campaigns. A dominant figure in local Democratic politics as a fundraiser and strategist and a longtime friend of Melius, he held the wedding of a daughter at Oheka in 2013.

Israel did not respond to requests for an interview and it’s unknown if the wedding was discounted, a favor Melius frequently offered to friends and political allies.

Councilwoman Marlene Budd, who joined the town board in 1996 and married Israel in 2003, became Melius’ lawyer in 1998. She abstained from voting on Oheka matters after that. Budd later became a Family Court judge.

A Melius company, ArchCon, designed plans in 2004 for a remodeling project in the Dix Hills home Budd shared with Israel, her then-husband. Melius also held in-kind fundraisers at Oheka — in which services are donated — for Israel and Budd.

In addition, since 2005, the Huntington Town Democratic Committee has received at least $25,500 from Melius and his family members. Israel, Budd and Cuthbertson are all Democrats. Petrone changed parties to become a Democrat in 2002.

‘The floating castle district’

Despite this record of support, Melius faced a daunting prospect when he tried once again to legalize the castle’s operations. Residents of Oheka’s quiet upscale neighborhood, still upset by traffic, noise and previous battles with Melius, had mobilized against him. They collected 300 signatures on a petition against his plans and hired an attorney, John Flanagan, currently the Republican majority leader of the State Senate, to fight him.

In place of the obstructionism of the past, Melius retained a respected former town attorney and zoning expert, Arthur Goldstein, who aside from his formidable expertise was known for his charm, humor and personal modesty.

Goldstein also knew more about the town zoning code than anyone else because he had written it. For Melius, he invented a new zoning category tailor-made for Oheka. It was confined to officially designated historic properties of more than 15 acres. That description fit only Oheka. It was crafted to allow commercial use in the name of generating revenue to assist in what was now portrayed as Melius’ singular mission, preservation.

Goldstein called the category a “historic overlay district.” In Huntington, as in many areas, there is a firm prohibition against what is known as “spot zoning” — a zoning designation that applies to only one property. While Oheka was the only property affected, the “overlay district” did not directly refer to Oheka.

Among town officials it was known as “the floating castle district.”

Goldstein launched a charm offensive, meeting with neighbors, and received big support from Ellen Berkowitz Schaffer, an assistant town attorney and a local civic leader, and Joan Cergol, a public relations specialist. Five years later, Cergol became a special assistant to Petrone. In December, she was appointed to the town board.

Under her guidance, the castle was opened for public tours that filled up with schoolchildren and town residents.

A nonprofit, Friends of Oheka, was created to support and accept donations for the restoration. Several years earlier, Melius had named Schaffer, a close friend, the castle’s curator. She was deeply involved in creating Friends of Oheka and later became its board president.

“The truth was that he performed miracles there and saved us from the horrors of an empty building that was attracting teenagers,” Schaffer said in an interview.

Melius began connecting with the influential Cold Spring Hills Civic Association. He invited members to Oheka and allowed them to hold free parties there, as well as association meetings. He hosted holiday events for neighborhood children.

Schaffer was the civic association’s past president and an adviser to its board. At her urging, it decided to support Friends of Oheka, arguing that Melius needed an ample revenue stream for the restoration.

Goldstein took note of neighborhood concerns and acknowledged them in the restrictions that accompanied the new zoning category. The final proposal allowed for the hosting of only one event at a time, with no more than 220 guests. The castle’s exterior could not be altered and only one small “Oheka” sign was permitted. Perhaps most significantly, the building could not be expanded, limiting the possibility of truly large events.

By the time the town board took up Goldstein’s proposed new zoning category in December 1997, civic association members were holding their meetings at Oheka, residents were touring the castle and their children were attending spectacular holiday parties there.

The resolution to approve the “floating castle zone” was sponsored by Petrone, Huntington’s supervisor.

News accounts reported that hundreds attended the board’s hearing, with 19 speakers, according to the official transcript. Civic association members and professional experts on Melius’ team were among those who spoke in support.

Because she was a town attorney, Schaffer said at the meeting that it would be “totally inappropriate for me to comment.” She then presented a slideshow on the castle’s history.

Ted Owens, then the president of Friends of Oheka, told the board that permitting “some limited commercial use” was essential to the castle’s survival. “It is only these operations that do generate enough money to maintain and restore the building,” he commented. He said, though, that the operations had to be limited, as they were in the proposed restrictions, to minimize the impact on the neighborhood.

Among the opponents was Dunn, the target of Melius’ $10 million suit. She said she wondered why the board would even consider a zoning provision for Melius after he had ignored safety and zoning regulations for years. She asked why they would allow him to operate a large business in a residential neighborhood, disrupting the quiet life she and her neighbors had once enjoyed.

“I don’t understand how zoning codes and fire codes and safety laws go completely unchecked,” Dunn said. “I don’t understand how property taxes remain in arrears, yet this board continues to entertain this application. None of this seems to matter.”

And she expressed astonishment that no one on the town board felt compelled to come to her defense after Melius’ libel lawsuit, which was based on her public comments and her correspondence to the town as a Huntington citizen.

“He seeks out his most vocal opponent and sues her for $10 million, and what does the town board have to say about that?” she said in frustration. “Nothing.”

In the end, the board voted unanimously to approve the new zoning category that allowed commercial use of Oheka, a little more than a year after the zoning board had rejected Melius’ last attempt. In addition to Petrone, board members Budd, Israel, Donald Musnug and Susan Scarpati-Reilly approved the zoning.

The board’s action, Petrone said, enabled the castle to become “a benefit to that community.”

The complaints about noise and fire hazards were routine in issues of this sort and Melius’ donations had nothing to do with the council members’ votes, he said.

Petrone said Melius worked hard to win over the community. “That was Gary’s basic mode of operation,” he said. “He would come in and want to be part of the political process. My guess? He probably contributed to all the politicians on Long Island.”

Restrictions eased

The libel suit against Dunn, who declined to be interviewed for this story, was eventually settled. She moved out of the neighborhood.

But at the tumultuous hearing, she cautioned that the zoning change was likely the first step toward something further. “I have a very strong feeling that he is just getting warmed up,” she said.

She was right. Virtually every important restriction enacted in 1997 was eliminated or eased over the next few years.

In 2002, the board relaxed the limit on the number of guests at events and removed the ban on building expansion.

In 2003, it allowed construction of a temporary banquet facility.

In 2004, it permitted Melius to add signs and approved operation of a 50-room hotel and a health spa, which has yet to be built.

Petrone said that while he couldn’t remember specifics, the changes had community support. “Anything that took place at Oheka the community was involved in and spoke for,” he said.

Melius portrayed things similarly. His neighbors, he said, told the board, “Give him what he wants. We trust him.”

Soon, the number of events was burgeoning. Celebrity weddings hit the entertainment pages regularly. John Gotti Jr.’s lawyer promoted boxing matches through a company called Explosion Promotions. Political meet-and-greets became a staple.

The board’s decisions were worth tens of millions of dollars.

Melius repurchased the castle from Yokoi’s family during a booming real estate market in 2003. He paid $6.9 million, roughly $15 million less than the recorded price that Yokoi had paid 15 years earlier.

But Melius still held onto an idea for a bigger score — a condo development on the grounds, on a far grander scale than he had envisioned years before.

By now, he had demonstrated that he was a bona fide political player.

Intro:

Intro: Video:

Video: Chapter 1:

Chapter 1: Chapter 2:

Chapter 2: Chapter 3:

Chapter 3: Chapter 4:

Chapter 4: Chapter 5:

Chapter 5: Chapter 6:

Chapter 6: Chapter 7:

Chapter 7: