One man’s rise shines light on LI’s corrosive system

One man’s rise shines light on LI’s corrosive system

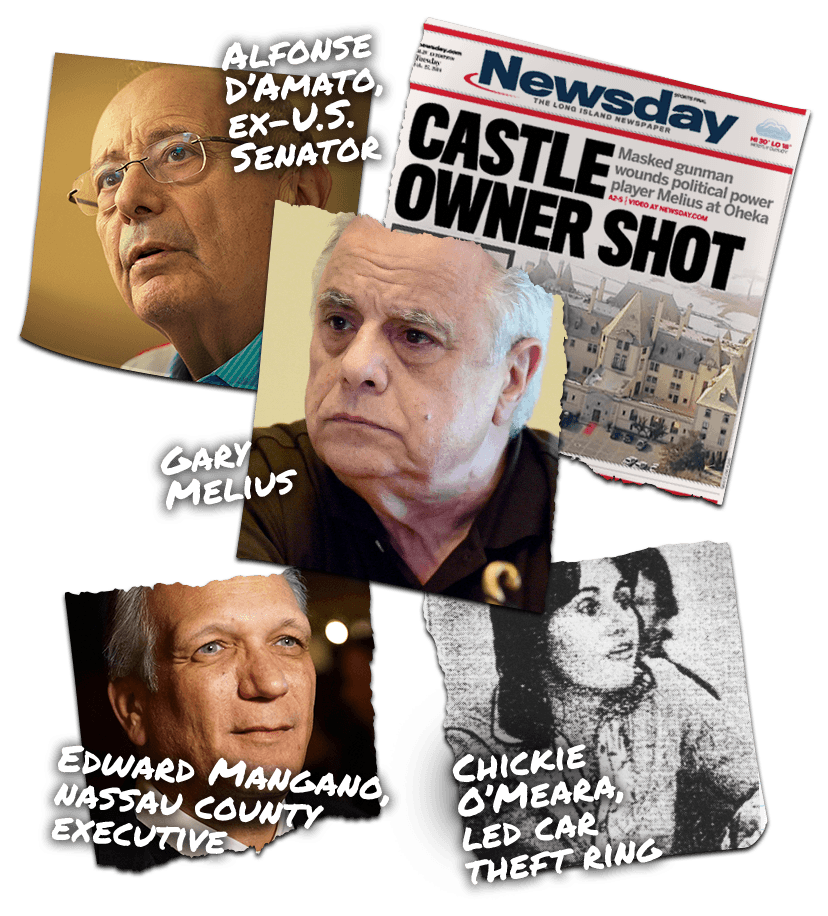

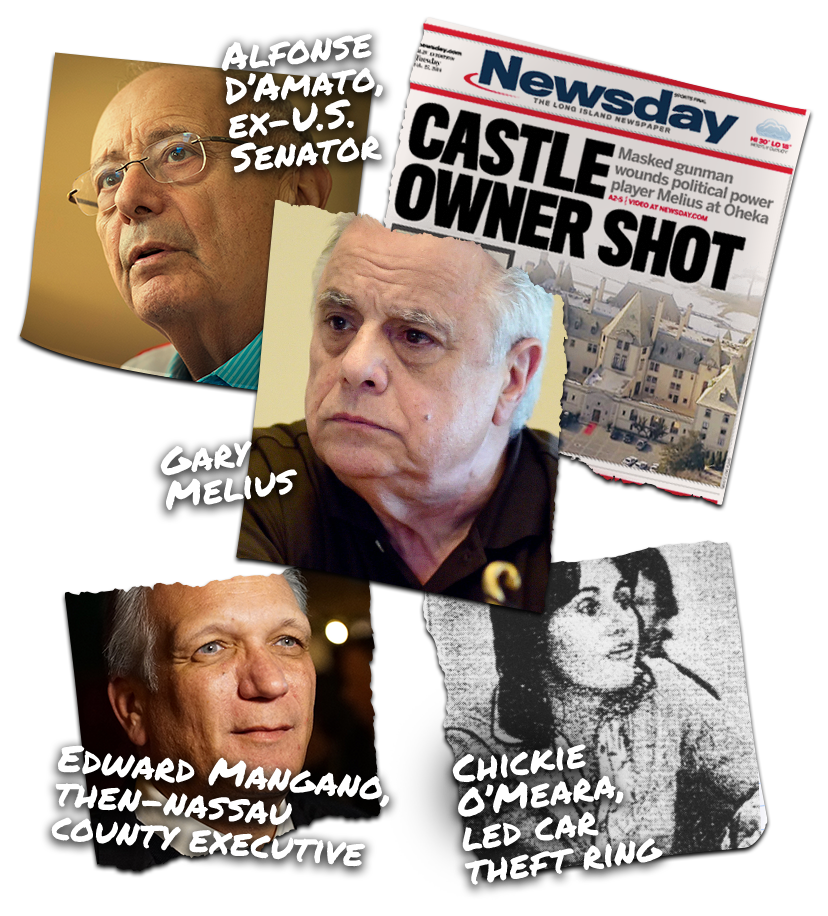

Gary Melius has transformed himself from onetime West Hempstead street tough to owner of a Huntington castle that became Long Island’s unofficial political clubhouse. He made his way from the outside in as a player with powerful friends and a practical understanding of the day-to-day workings of the Island’s cozy, transactional political structure.

Melius, who was shot and wounded four years ago in the shadow of his greatest accomplishment, Oheka Castle, didn’t invent Long Island’s way of doing business. But through him, a portrait emerges of how the game is played and how hard it may be to change.

Deals, cop contracts: Learning from the masters

Deals, cop contracts: Learning from the masters

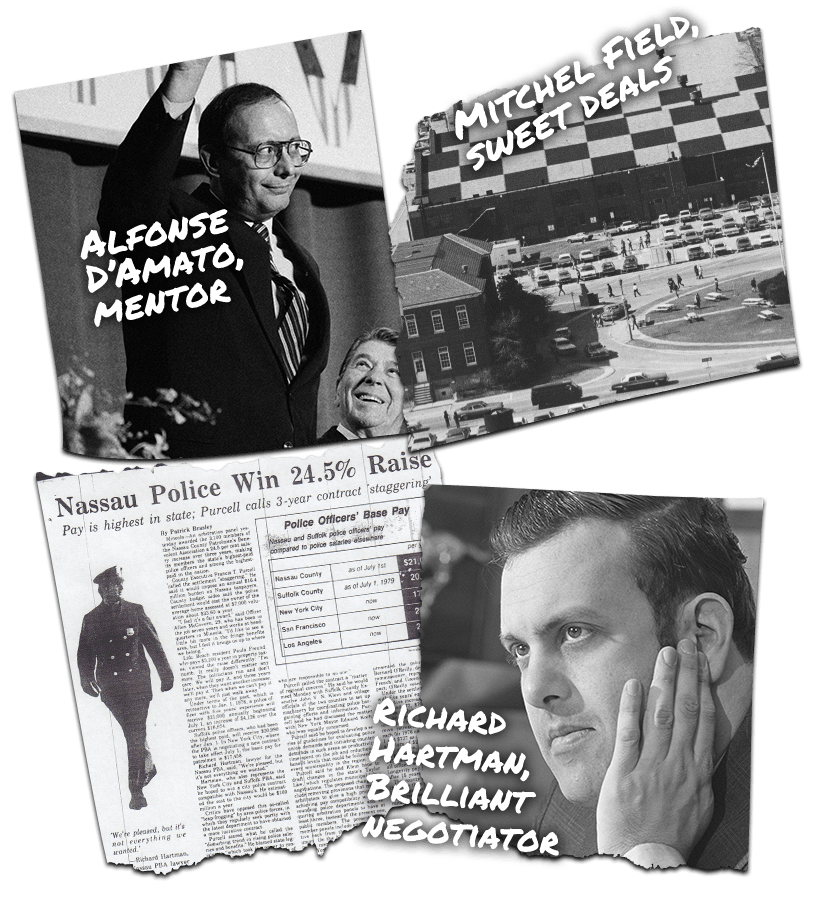

By the mid-1970s, Melius was making his way on Long Island, having emerged from five sets of criminal charges without jail time. Largely responsible was brilliant, politically connected lawyer Richard Hartman, who became one of his two great mentors. The other was Alfonse D’Amato, and the ’70s were when D’Amato and Hartman first scored big.

Hartman won police contracts that made the counties’ officers among the highest paid in the country. D’Amato rose from Hempstead supervisor to U.S. senator.

D’Amato toughed out an investigation into kickbacks by town employees to the Republican Party; allegations of favoritism in placements into subsidized housing in his hometown, Island Park; and a district attorney’s report that concluded politically connected developers had received below-market leases on valuable properties in Mitchel Field.

Melius, meanwhile, bought Hartman’s headquarters building and, using politically involved lawyers, built a property portfolio worth millions. He joined civic boards. His foundation, named for his mother, made the first of what would become $2.8 million in charitable donations. He gave $1,000 to D’Amato’s 1980 Senate campaign, which he would follow over decades with more contributions to a range of politicians.

Casino flop: Struggling outside LI’s cozy network

Casino flop: Struggling outside LI’s cozy network

One way to measure the sustaining power of Long Island’s network of insiders is to witness how Melius struggled during the ’90s, when, operating outside his network of political connections, he tried to rebound from a financial meltdown.

A recession and tax law changes sent his finances reeling. Five of his companies went into bankruptcy, and at one point he was more than $20 million in debt. He also owed more than $250,000 to casinos, most of it to ones owned by Donald Trump.

Trying to rally, he managed boxers, invested in a sexploitation film and joined forces with a prodigal member of the Gucci family in a fashion business. Most of these ventures failed.

In a last move, he tried to start a casino on a remote upstate Indian reservation with a Long Island partner.

The rise of Oheka Castle

The rise of Oheka Castle

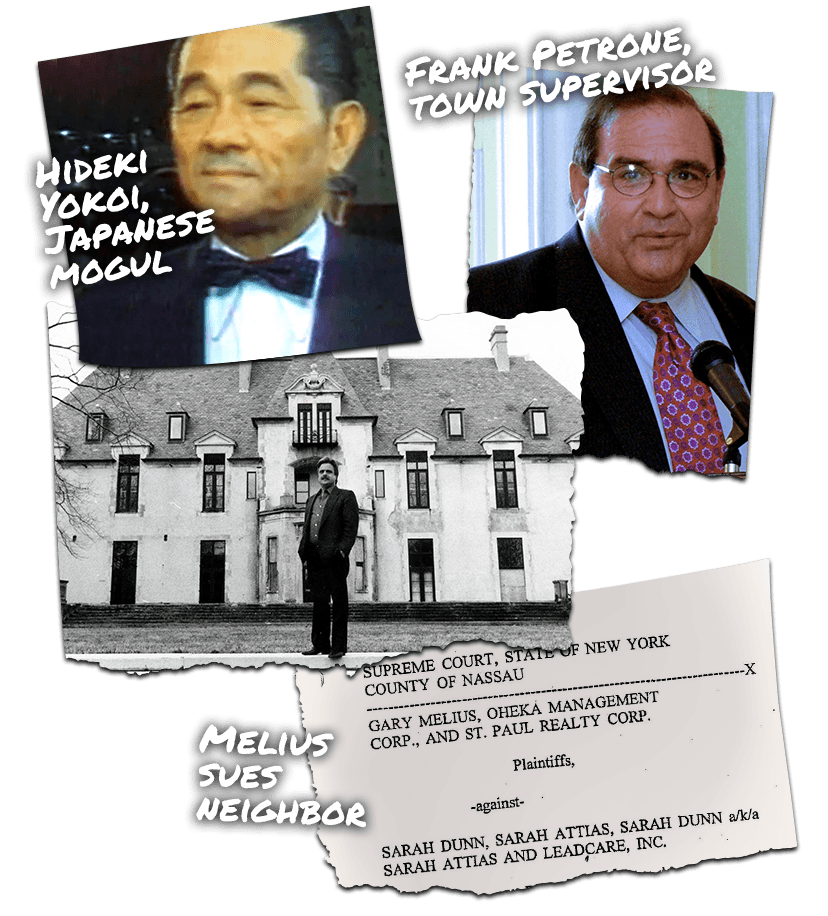

Gary Melius received an unexpected call in 1988. It came from a broker for a Japanese billionaire facing prison time for a fatal fire in a hotel he owned that lacked sprinklers. He wanted to buy Oheka Castle.

The billionaire was moving assets out of Japan as he awaited his fate. He paid a recorded price of $22.5 million for Oheka. He also allowed Melius to live at the castle and manage it.

But soon Melius began amassing code violations for fire and building hazards and illegally hosting weddings and flea markets. By 1997, he owed more than $600,000 in taxes and Huntington had sued to shut the castle down. Melius waged a consummate counteroffensive, though, that showed his rising skill as a power player. Despite his past record, the Huntington Town Board allowed him to operate Oheka commercially. The board placed significant restrictions on the use of the castle, but within a few years it had eliminated or eased virtually every one of them. In 2003, Melius bought back the castle for $6.9 million.

A multimillion-dollar taxpayer bailout

A multimillion-dollar taxpayer bailout

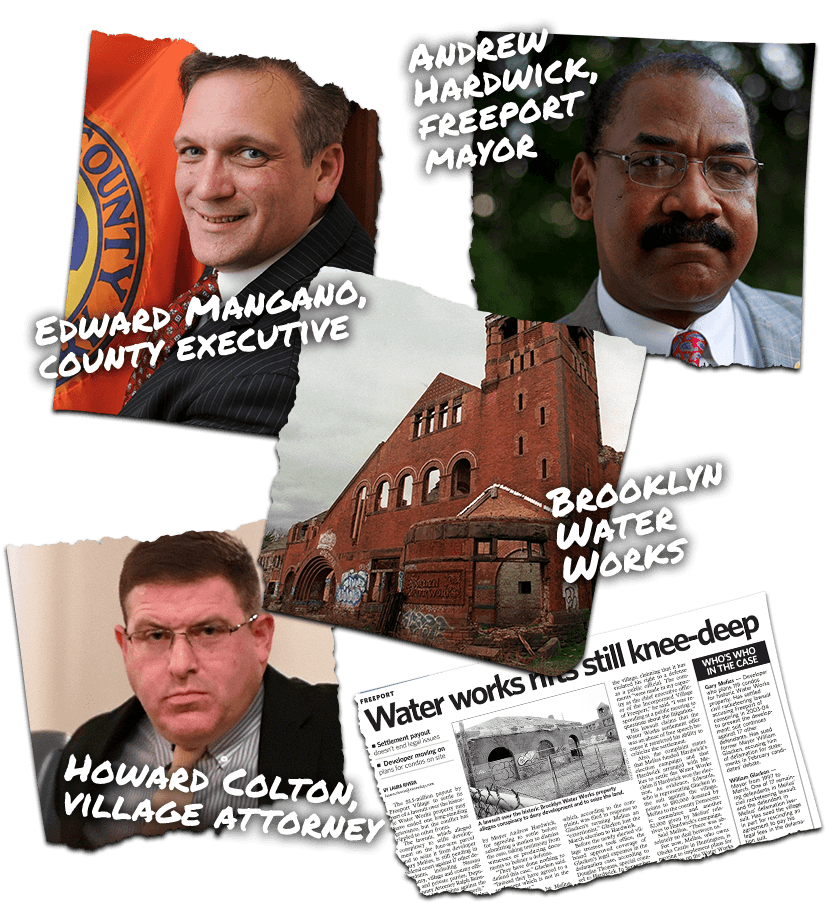

As Oheka thrived, a Melius property in Freeport bled money. Called Brooklyn Water Works, it was anchored by an abandoned 19th century pumping station. Melius had tried to redevelop the property unsuccessfully for two decades. He said Water Works had cost him millions of dollars and was waging legal war over the property with the village.

Freeport’s attorney told police in 2009 that Melius employed threats against him to pressure the village to settle.

How he worked his way out of the project at public expense reveals how Melius had come of age as a power broker.

In 2009, he threw his support and contributions into the successful insurgent mayoral campaign of Andrew Hardwick. Then he quickly cemented ties with the newly elected county executive, Edward Mangano.

Their two administrations would spend a combined $11 million in public money on the property, including $6.2 million that – based on questionable valuations – Nassau County spent to buy it. And the village lawyer never pressed his complaint. He became an Oheka regular.

A politically motivated arrest on a public bus

A politically motivated arrest on a public bus

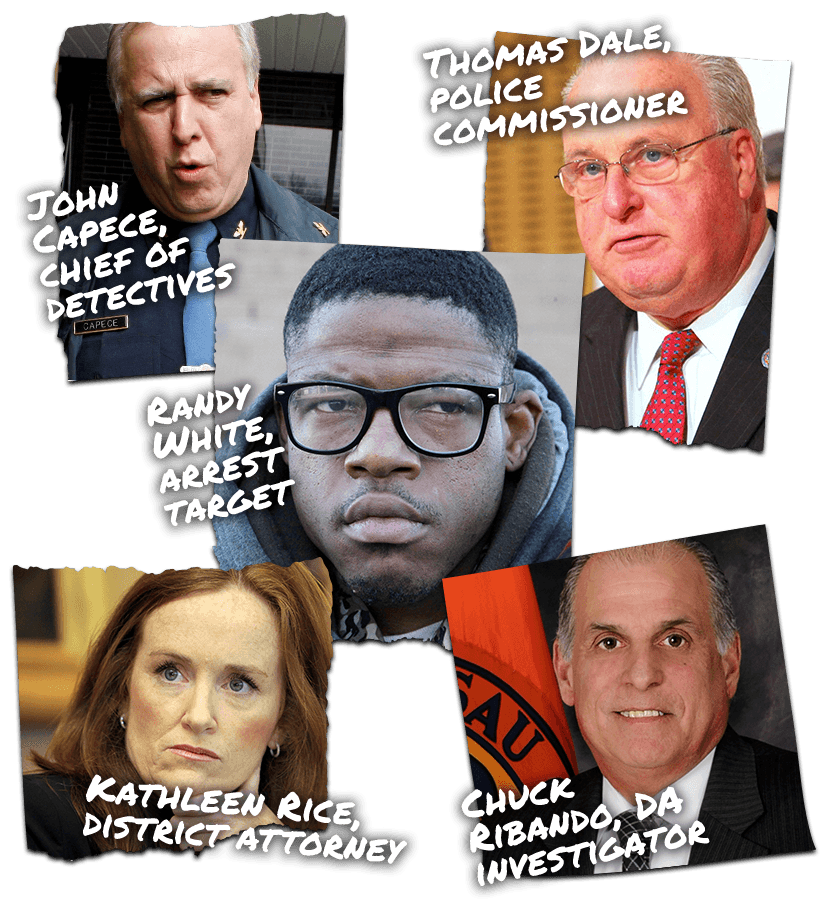

In 2013, Randy White, a man with a learning disability, was pulled off a bus and arrested. White wasn’t a wanted felon, but he had given testimony that jeopardized Andrew Hardwick’s third-party bid for Nassau County executive. Hardwick’s candidacy, financed largely by Melius, could have helped Nassau County Executive Edward Mangano, a Melius ally, by diverting votes from his Democratic challenger.

White testified he was paid by the signature for petitions, an election-law violation that threatened Hardwick’s candidacy. According to a report by Nassau District Attorney Kathleen Rice, Melius called his friend, Thomas Dale, the Nassau County police commissioner, and said the Hardwick campaign “wanted to file a perjury charge against” White. Officers found no evidence of perjury, but they did find an outstanding warrant issued for White’s failure to pay a fine in a misdemeanor case involving bootleg DVD sales.

Police jumped White’s warrant ahead of 50,000 others and jailed him, setting off a furor. Rice’s report found much of what happened from there troubling, but not criminal. Still, Dale resigned under pressure and his chief of detectives decided to retire rather than be demoted. White filed a lawsuit against the county, citing civil rights violations, and won a $295,000 judgment. Newsday has found unreported information raising new questions about the scandal.

With new players, will LI’s entrenched system survive?

At its peak, Oheka Castle has been a place of celebrity weddings, pop star videos and $1,000-a-night hotel suites. It also has been Long Island’s unofficial political clubhouse, filled with party endorsement meetings, political tributes and fundraisers, exclusive poker games and man-cave cigar gatherings.

At its low point – four years ago this Saturday – Melius was nearly assassinated in its rear parking lot, in a still-unsolved crime.

A lot has happened since then. Melius says his health and finances have suffered. His bank has sued to foreclose on Oheka. And several of his friends in politics and law enforcement have been indicted or imprisoned. Newcomers, espousing reform, have emerged.

But a look at Melius’ half-century on the scene shows both his resiliency and the staying power of the entrenched and lucrative political system he travels in.

Whether Melius can rebound remains to be seen. More importantly, is it possible to fundamentally change Long Island’s troubling way of business, and, if so, how easily?

This project was reported and written by Gus Garcia-Roberts, Keith Herbert, Sandra Peddie and Will Van Sant with contributions from Aisha Al-Muslim, Matt Clark, Paul LaRocco, Maura McDermott and Adam Playford. It was edited by Martin Gottlieb and Alan Finder. Mike King and Mark Tyrrell were the copy editors; Caroline Curtin, Dorothy Levin, Laura Mann and Judy Weinberg were the researchers.

Production: Saba Ali, Jeff Basinger, Raychel Brightman, Daryl Becker, Anthony Carrozzo, Matthew Cassella, Bobby Cassidy, Tara Conry, Susan Yale, Mario Gonzalez, Joseph Hegyes, Greg Inserillo, Sumeet Kaur, John Keating, Jessica Kelley, TC McCarthy, Ryan Restivo, Chris Ware, Yeong-ung Yang

Photo credits: Michael E. Ach, Nick Cardillicchio, Bill Davis, J. Michael Dombroski, Chuck Fadely, Thomas A. Ferrara, Elliott Kaufman, Dick Kraus, Patrick E. McCarthy, Robert Mecea, Megan Miller, John Paraskevas, Jim Peppler, David L. Pokress, Alan Raia, Howard Schnapp, Barry Thumma/Associated Press, Chris Ware, J. Conrad Williams Jr., Stan Wolfson, Nassau County Government, Associated Press