A politically motivated arrest on a public bus

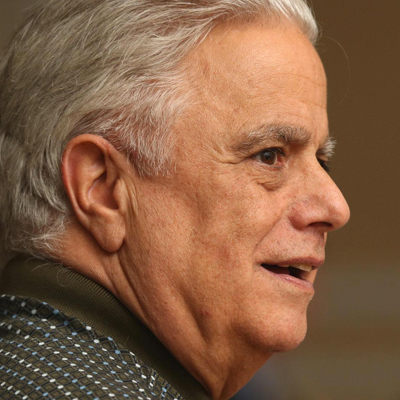

Gary Melius, the county executive’s race and the case of Randy White

A sergeant and two plainclothes detectives from the Nassau County Police Department stopped a bus in Hempstead Village on an October evening in 2013 and arrested Randy White as he was traveling to visit his nieces.

White’s apprehension and the incarceration that followed came days after he had given critical courtroom testimony against Andrew Hardwick, an ally of Gary Melius, that threatened to upend the Oheka Castle owner’s effort to sway the pending Nassau County executive race.

White’s testimony so troubled Melius that he telephoned Nassau Police Commissioner Thomas Dale, a friend whom Melius had recommended for the job, to say that Hardwick’s county executive campaign “wanted to file a perjury charge against” the 29-year-old White, according to findings District Attorney Kathleen Rice issued after her office investigated the case.

When Dale’s officers could not find evidence of perjury, they found another justification for apprehending White: an outstanding warrant — one not even entered in the department’s computer system, according to a sergeant involved — issued for White’s failure to pay a fine in a misdemeanor case involving bootleg DVD sales.

Following Melius’ call, police jumped White’s open warrant ahead of 50,000 others. Half were arrest warrants, which involve criminal violations and are supposed to be the department’s priority. Roughly 2,000 were felony warrants. White’s warrant was a bench warrant, typically issued for noncriminal violations like failure to pay traffic tickets. At the time, there were 25,000 open bench warrants in Nassau.

Hardwick was then a long-shot, third-party candidate for Nassau executive. Victory was unlikely, but his fledgling campaign had the potential to draw votes away from the Democratic challenger to Republican Nassau Executive Edward Mangano, a Melius friend and ally.

The political motivation for White’s arrest became all the more apparent when the sergeant served him with a civil subpoena from Hardwick’s attorney while White was in police custody. The campaign of Hardwick, a former Freeport mayor, wanted White back in court to re-examine him. Earlier he had testified that he’d been paid by the signature when collecting petitions for Hardwick, a violation of state election law that could endanger a campaign.

In targeting White, who has a learning disability, Melius acted not against another player in the bruising arena of Long Island politics, but a vulnerable civilian whose sworn court testimony had created a political obstacle. Top Nassau law enforcement leaders, some with personal ties to Melius, led the arrest effort.

Rice’s investigation determined that the incident, while troubling, did not include criminal misconduct warranting prosecution or involve Mangano or those in his administration. Newsday, however, has discovered unreported information that raises new questions about the scandal.

Melius emails District Attorney Rice

Key police officials at the center of the White matter told Newsday they were interviewed not by Rice’s investigators but by Nassau police internal affairs personnel. They include Dale’s chief of detectives, John Capece, who helped lead the effort to apprehend White. Interviews given to internal affairs investigators are generally criminally inadmissible, meaning Rice’s inquiry was conducted in a way that complicated or even precluded potential prosecutions.

In an interview, Capece told Newsday that he cautioned Dale against arresting White. But Capece said the police commissioner confided that he had no choice, saying that “he was getting pressure from people across the street.” Mangano’s office was across from police headquarters, and Capece said he understood Dale to be referring to the county executive, a Melius ally and the potential beneficiary of the election scheme, and his deputy, Rob Walker.

Dale, Mangano and Walker declined interview requests. They were among several pivotal figures in the White drama who chose not to answer questions from Newsday.

While the scandal led to Dale’s resignation and Capece’s decision to retire rather than be demoted, Melius and many public officials who abetted White’s arrest paid no price, unlike Nassau taxpayers. White, whose father said his son was left “psychologically bent” by the episode, brought a lawsuit against Nassau that alleged an array of civil rights violations and collected a $295,000 legal settlement in 2016.

Bennett Gershman, a Pace Law School professor and former public corruption prosecutor, expressed dismay not only at the actions of Melius and Nassau police, but also at the failure to pursue criminal charges in “a case of rank corruption.”

“You’ve got this power broker who picks up the phone to the chief of police and gets a man yanked off a bus and arrested,” Gershman said. “It’s terrifying.”

Independence Party ties

The White scandal sprang from machinations to keep Mangano in office.

In 2009, Mangano won an upset victory over Nassau Executive Thomas Suozzi by 386 votes out of nearly a quarter-million cast. Plans were made to prevent any such scare in the 2013 rematch. They involved using third-party spoiler candidates to siphon away the votes of environmentalists and African-Americans who would be likely to support Suozzi, a Democrat.

Melius and his wife, Pamela, had donated nearly $18,000 to Mangano during his first term, and Melius had reason to want him re-elected. With Mangano in office, Nassau had inked a real estate deal, legal settlement and contract with Melius worth more than $7 million to the castle owner. The county also tweaked its rules on the use of ignition interlock devices that combat drunken driving, benefiting a company in which Melius had a stake.

Backing Mangano in 2013 after having supported Suozzi in 2009 was the Independence Party, a controversial third party with which Melius and his beloved Oheka Castle had become deeply enmeshed.

Independence Party’s road to prominence

In 2008, Melius established an alliance with Frank MacKay, the party’s state and Suffolk County leader. MacKay named Melius his “chief adviser” that year in an effort to take the party national. The designation elevated him in a party whose modest size belies its clout, particularly in judicial races, and that’s described by some in state politics as an elaborate con.

In part, that’s because new voters have mistakenly registered as Independence Party members when they intended to register as independent of any party.

“They don’t stand for a thing,” GOP gubernatorial candidate Rob Astorino said of the party’s leadership during his failed 2014 run, “other than jobs for themselves.”

Astorino was expressing a frequent criticism, that the party is effectively a mechanism to exert influence and generate income for its leaders, rather than a standard-bearer for any political ideology. It’s a criticism party leaders reject, but one voiced by editorial boards and good-government advocates across the state.

At the time of the 2013 election, Oheka Castle had become the party’s de facto operations hub, a place to hold fundraisers and interview candidates. MacKay had named Richard Bellando, Melius’ employee, friend and former son-in-law, as the party leader in Nassau. And Oheka had put MacKay on its payroll in various positions.

MacKay declined to be interviewed for this story.

Spoiler candidates

The hand of the Independence Party was evident in two aborted efforts to use third-party candidates to strip votes from Suozzi and to aid Mangano’s re-election.

The first involved 25-year-old Phillipp Negron, who was recruited to run for executive on the Green Party line and had landed a public works job with the Mangano administration just days before his campaign became public. Negron would testify in an election law case involving his campaign that he decided to run after speaking with his stepfather, Timothy Williams, a Mangano appointee and chairman of the Nassau Industrial Development Agency. After the talk, he said, a woman brought a Green Party registration form to his home.

Negron testified that he and his stepfather next met a man at a diner who brought paperwork to sign. “When I registered to be a Green Party member, I expressed my interest in running,” Negron said. “Next thing I know, I’ve been nominated.”

The man he and his stepfather met at the diner was Brian Nevin, Mangano’s former chief spokesman and manager of his re-election campaign, Negron testified. The bulk of the petition signatures Negron needed to get on the ballot would be collected by Nevin and other Republicans working for Mangano, court records would establish.

Robert Pilnick, an Independence Party officer, was also among the handful of political operators who collected signatures, county election records show.

Democrats challenged Negron’s petitions in court, alleging that the campaign was a “fraud” and that some signatures were from reluctant Oheka Castle employees. After two days of testimony, Negron withdrew from the race.

Invalid signatures

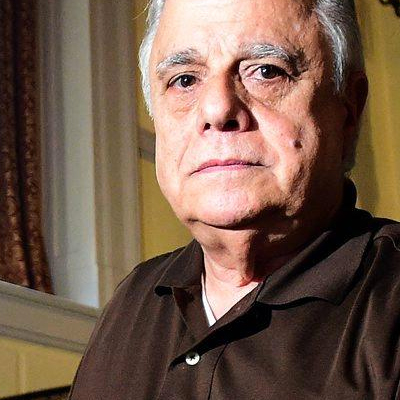

The Independence Party’s attorney was involved in the second effort, which featured Hardwick, who tried to run as a candidate for the new “We Count” Party.

After a tumultuous term as Freeport mayor — during which he backed $4.4 million in settlements for Melius in cases involving his troubled Water Works property — Hardwick had lost a re-election bid.

Hardwick’s party was a creation of Melius and his allies. Between July 2013 and the November election, records show Melius, his family and one of his businesses gave We Count $38,839, more than 80 percent of the party’s total.

Because Hardwick is black, many people in Nassau politics saw his candidacy as an effort to siphon African-American votes from Suozzi. The candidate, however, insisted that his run was a stand for the middle class and against corruption.

“People are sick and tired of the same old lies and deceit,” Hardwick said in a campaign video.

After Nassau Democrats challenged Hardwick’s petitions in state court, state Supreme Court Justice F. Dana Winslow barred him from the ballot, declaring that his petition effort had been “permeated with fraudulent practices” of which Hardwick had “knowledge.”

While the case was in court that October, the board of elections found 2,700 of Hardwick’s 8,400 nominating signatures invalid. It was suspected that thousands more were outright forgeries, but Winslow, with the consent of both parties, ceased his review after identifying more than 100 such bogus signatures.

Asked to identify his largest campaign donor, Hardwick replied under oath, “I don’t know.”

At the time Hardwick testified, Melius was his sole donor. His campaign treasurer was an Oheka employee, and a campaign worker testified that she had delivered nominating petitions to Hardwick at Oheka. Independence Party attorney Vincent Messina, whose firm collected $16,000 from We Count’s largely Melius-funded treasury, represented Hardwick in court.

Hardwick declined interview requests.

A call to the commissioner

Randy White emerged as a key witness in the Hardwick case.

As a teenager, White had compiled a criminal record, including convictions for attempted robbery and felony drug possession. Through his 20s, however, White stayed out of legal trouble, save for an occasional misdemeanor violation for selling bootleg DVDs.

He lived at home with his father, Rassan Hoskins, a Nassau Democratic Party committeeman, and struggled to find work. When Hardwick operatives asked White to collect signatures to get Hardwick on the ballot, White agreed.

“Randy naturally wanted to make some money,” Hoskins said. “But I told Randy, ‘Man, you can’t work for Hardwick, I am a Democrat.’ ”

Hoskins said his son “is not sophisticated enough” to always recognize when he’s being used and can be truthful even when doing so could cause him grief. Under questioning in the Hardwick case, White testified that he’d been paid by the signature, which is prohibited by state election law in part because it’s thought to incentivize fraud.

Two days later, on Oct. 4, Hardwick’s attorney Messina unsuccessfully attempted to introduce a telephone call recorded by campaign operatives in which it was alleged White contradicted his damaging testimony.

Within hours, according to findings that District Attorney Rice released six weeks later, Melius called Nassau Police Commissioner Thomas Dale, whom he had recommended Mangano appoint, and said Hardwick’s campaign “wanted to file a perjury charge against” White.

Dale sent some of his top people, a department attorney and Capece, the chief of detectives, to the First Precinct in Baldwin, according to the Rice findings. There they met with Hardwick campaign operatives and Messina, the candidate’s attorney who also represented the Independence Party, to discuss the perjury charge. The recorded phone call turned out to be inaudible, Capece said in an interview, and he told Dale that he would not arrest White for perjury.

Police soon found other grounds, however.

Sal Mistretta, then an Oheka regular and a Nassau police sergeant who led the pistol license division, played a central role in the scandal. At the time, Mistretta was backing Mangano’s re-election. He gave $500 to the incumbent on Oct. 18 and was listed as a contact on a flyer for an Oct. 28 Mangano fundraiser.

In a recent interview, Mistretta said that he checked the department’s electronic warrant system on the day of the First Precinct meeting and found no hits for White. Nonetheless, he said, an outstanding warrant was located, presumably in court filings, and faxed to the precinct after 5 p.m.

The warrant involved White’s failure to pay a $175 misdemeanor fine, $25 victim assistance fee and $50 DNA databank fee levied in a bootleg DVD case in which White was sentenced to 14 hours of community service after he pleaded guilty. All guilty verdicts in New York State require the levying of such fees.

The warrant had been issued on Aug. 26, almost six weeks before the meeting at the First Precinct, and until that moment it had apparently not been an urgent matter. Between the day it was issued and the First Precinct meeting, White had appeared in court several times and spent 10 days in jail on another DVD case, but he had not been picked up on the warrant.

When news of the warrant reached Dale, he ordered White located and arrested, despite what Capece said were his cautions to the commissioner.

Using information from an individual Dale would later describe to investigators as a “confidential source” who appears to have tracked White, he was located the following evening. A sergeant and two detectives handcuffed White on the public bus and took him to the First Precinct, where he was given a strip and cavity search, according to his federal civil rights complaint.

White was then taken to police headquarters, where Mistretta served him a civil subpoena drafted by Messina, the Independence Party’s attorney, who was representing Hardwick.

The subpoena ordered White to appear in court the following Monday so that he could be questioned about his prior testimony. Mistretta said he’d been given the subpoena by Brandon Irizarry, who worked on the Mangano and Hardwick campaigns. Though not a police officer, Irizarry mixed regularly with Melius and his many law enforcement guests at Oheka. Mistretta would later insist that he did not know that what he’d passed along was a subpoena.

Police next took White to the county jail, where, his federal complaint states, he was again subject to strip and cavity search. A judge released him the next day.

In comments to Newsday shortly after he left jail, White said he felt fearful and perhaps a bit paranoid. “It’s got me scared to go outside my house,” he said, “because I don’t know if the police think I got Andrew kicked off the ballot.”

Link to prosecutor’s office

Rice, who is now a congresswoman, began her investigation shortly after details of White’s arrest became public and would convey her findings to Mangano by letter, assuring the county executive that it was “appropriate to note our investigation has uncovered nothing to suggest that you or members of your administration were involved in the case against Mr. White.”

Chuck Ribando, Rice’s chief public corruption investigator whom Mangano would hire the following year as his deputy for public safety, helped lead the White inquiry.

By Melius’ own account, Ribando had been a frequent guest at Oheka and the two men enjoyed a friendship that went back years.

In 2009, Freeport Village Attorney Howard Colton alleged that Melius was using Ribando to bully him. Melius was engaged in an effort that eventually succeeded to settle a lawsuit he’d brought against the village involving his Water Works property.

Colton went to village police to complain that Melius had corrupted the district attorney’s office and was using Ribando and the threat of getting Colton indicted to secure a settlement. At one point, Colton told police, he met and was questioned by Ribando after Melius told him to seek out the investigator before the district attorney’s office came to “get” him.

Ribando declined repeated requests for comment.

In 2012, when Ribando’s daughter’s wedding reception took place at Oheka, an overnight affair that saw all rooms booked, Melius said in an interview that he had charged a discount and suggested that may have been because he’d been unable to line up any other event for the date in question. Mistretta and others who frequented Oheka said Ribando regularly attended the cigar parties Melius held at the castle and enjoyed Johnnie Walker Blue Label Scotch.

On Election Day in November 2013, as the Rice inquiry was underway, Melius sent Ribando a get-out-the-vote email that Newsday obtained through a records request. “Just a reminder to vote today,” Melius wrote. “Please consider voting Row E, the Independence Line — where you will find the best of all parties.” A November 2013 ballot showed Mangano and Rice were among dozens of candidates featured on the Independence Line.

Internal affairs involvement

Rice’s letter announcing the results of the inquiry was released on Dec. 12, 2013. She concluded there was no evidence of criminal misconduct by police brass.

While the case had “obvious political overtones” and Dale’s decision to involve himself was “a judgment potentially fraught with peril,” Rice found that “the department’s decision to target the subject of an open warrant was not a violation of criminal law.”

However, Rice noted that her office would continue to investigate White’s having been served with a civil subpoena by the Hardwick campaign while he was in police custody, which she called “a deeply troubling aspect of this case.”

“My office conducted a thorough investigation into these serious allegations,” she wrote.

Yet Mistretta and Capece, two lawmen central to the scandal, said in interviews that Rice’s investigators never spoke to them. Mistretta was the sergeant who delivered the Hardwick campaign’s subpoena to White while he was in police custody — the aspect of the case that Rice described as “deeply troubling” and “still under investigation by this office.” Capece, the former chief of detectives, had helped to carry out Dale’s arrest order. Mistretta said he knew of no others involved who were interviewed by the district attorney’s investigators.

After being told that Mistretta and Capece said they never spoke to any investigator from her office, Rice’s spokesman Coleman Lamb said by email that in fact the Nassau police Internal Affairs Unit had “conducted this investigation” with “oversight” from the district attorney’s office. Though Lamb said that was “standard” practice in such cases, the approach would require extraordinary steps to preserve prosecutors’ ability to bring criminal charges.

That’s because internal affairs units focus on violations of department rules and their investigators can use the threat of workplace sanction to compel interviews. Prosecutors, however, must honor the rights of individuals not to incriminate themselves and may not use such interviews to bring criminal charges.

In her letter, Rice, who declined to be interviewed for this story, stated that her office had reviewed “compelled departmental interviews” as part of its “consideration of potential criminal charges.”

“She should not have received any compelled interviews,” said Jeff Noble, a former Irvine, California, deputy police chief and now a law enforcement consultant who has written extensively on the issue of cooperation between prosecutors and Internal Affairs Unit investigators. “She could not use those interviews in any prosecution and the receipt of the interviews may have tainted her office from being able to conduct an investigation if there was independent evidence of a crime.”

Any valid criminal investigation, he said, would have required Rice to establish a “clean team” of prosecutors, none of whose members had seen the compelled interviews.

Asked how Rice expected to investigate potential crimes using internal affairs investigators, Lamb wrote “that’s a more detailed question than we can handle without having access to case files, notes and personnel at the DA’s Office.”

Lamb referred a reporter to the office of District Attorney Madeline Singas, who succeeded Rice in 2015. A spokesman for Singas recently declined to provide details of the investigation.

In response to a public records request Newsday made to the district attorney’s office, Singas provided portions of the White case file in early 2017, withholding some portions so as not “to reveal confidential information relating to a criminal investigation” and to avoid “unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.”

Newsday received White’s five-page notice of claim against the county in the civil lawsuit that resulted in his $295,000 settlement, 50 pages of related case law research and news stories, Rice’s letter of December 2013 and a two-sentence “final agency determination” from 2015 that found White’s in-custody subpoena service did not “warrant a criminal prosecution.” Newsday has asked Singas’ office how it was able to close that investigation without having interviewed Mistretta, the man who delivered the subpoena, but has gotten no answer.

The only other record the office provided in response to the records request was an email from White’s attorney to a prosecutor sent shortly after his client’s arrest that pointed out tens of thousands of warrants were then open.

Commissioner, chief of detectives out

On Dec. 9, 2013, three days before Rice issued her letter, Dale contacted Capece while he was vacationing in Florida and told him he had to come back to Long Island to be interviewed by internal affairs, Capece said. At the time, Dale was himself presumably a focus for investigators.

Capece said Dale told him not to worry because “directly from Kathleen Rice” he’d gotten everything “smoothed out” in regard to her soon-to-be-released letter.

Rice’s spokesman Lamb denied that such a conversation with Dale took place. “Is there any evidence at all to suggest it did,” Lamb wrote, “other than Mr. Capece claiming that he heard it second hand from Mr. Dale?”

The day Rice produced her letter, Dale resigned, under pressure from Mangano.

In an interview the following year, Melius called Dale’s ouster “the worst thing in my life.”

“It was worse than getting shot for me,” he said, adding that despite Justice Winslow’s decision to the contrary, he believed White had “perjured himself.”

The same day the Rice letter was released, Capece said, Mangano called him on speakerphone, saying he had “tragic news.” Mangano told him that he was at fault for the White debacle, Capece said, and that he had a choice: retire or be demoted to sergeant.

When Capece responded by saying he needed time to make such a decision, he said, Mangano deputy Rob Walker told him, “You have 15 minutes to make up your mind.” Walker also demanded to know whether he knew that he was obligated to refuse when asked to make an illegal arrest, Capece said.

He chose to leave the department.

“I don’t want to work for these people,” Capece said he remembers thinking.

The failure to bring criminal charges angered Nassau Democratic Party leader Jay Jacobs, who once backed Hardwick in a Freeport mayoral race and recruited Rice to run for district attorney in 2004. Jacobs said he was dismayed by Rice’s decision and aghast at the White affair, calling it “blatant witness intimidation.”

Jacobs is not alone in characterizing the episode as criminal. Gershman, the Pace Law School professor and former public corruption prosecutor, reviewed news reports that detailed the episode and said if the case had arrived on his desk, he’d have immediately empaneled a grand jury.

“This is just so outrageous,” Gershman said. “Do you have a conspiracy to violate White’s civil rights? Of course you do. Do you have official corruption? Of course you do. You have a lot of crimes here.”

Intro:

Intro: Video:

Video: Chapter 1:

Chapter 1: Chapter 2:

Chapter 2: Chapter 3:

Chapter 3: Chapter 4:

Chapter 4: Chapter 5:

Chapter 5: Chapter 6:

Chapter 6: Chapter 7:

Chapter 7: