Fair housing laws bar agents from directing whites to one community and equally qualified blacks, Hispanics or Asians to other places, a practice known as steering.

Even so, in 21 of 86 Newsday tests – 24 percent – agents located white and minority house hunters in areas that were different enough to suggest evidence of steering.

Robert Schwemm is a University of Kentucky College of Law professor and author of “Housing Discrimination: Law and Litigation.”

Elmont, a predominantly minority community, was suitable for a Hispanic house hunter but not for a comparable white one.

Freeport, an overwhelmingly minority village, could be a good place for a black home seeker but was a risky place to invest for a matching white tester.

Predominantly white Levittown was fit for a white buyer but more diverse East Meadow and Hicksville were appropriate for an African American.

Said one agent when speaking to a white customer: “I don’t want to use the word steer, but I try to edu – I use the word – I educate in the areas.”

Pointing out a need to study who lived in a community before buying, that agent, Rosemarie Marando of Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage, advised the customer to observe nighttime patrons of convenience stores.

“Wherever you’re going to buy diapers, you know, during the day, go at 10 o’clock at night, and see if you like the area,” she said, adding:

“There was one fellow who would – like insisted on this house, and the wife was pregnant and had a little one, and I said to him, ‘I can’t say anything, but I encourage you, I want you to go there at 10 o’clock at night with your wife to buy diapers. Go to that 7-Eleven.’ They didn’t buy there.”

“I have to say it without saying it, you know?” Marando confided.

She also counseled: “What I say is always to women, follow the school bus. You know, that’s what I always say. Follow the school bus, see the moms that are hanging out on the corners.”

Finally, Marando remembered hearing similar advice from an agent as a first-time homebuyer three decades ago and thinking, “What a creep.”

Marando made no similar comments when visited by a black tester. She gave both testers comparable listings in similar areas, showing no evidence of steering.

Newsday’s two fair housing consultants found that Marando had used “coded language” or “a euphemism” to describe steering while talking only to the white tester.

Based on information provided by Newsday, Robert Schwemm, law professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law, concluded:

“This agent knows what steering is and has come up with a euphemism for it that she is willing to share only with the white tester, not the black tester.

“Instead of ‘steering,’ she uses ‘location.’ She is saying she learned over time that this is particularly important. She is now displaying the behavior she criticized in her original agent. And not saying the same things to the black homebuyer is really problematic. Does she think minorities don’t want that?”

Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, concluded:

“This agent appeared to use coded language to urge the white tester to consider the racial composition of neighborhoods when considering where to buy a home.

“The agent said, ‘Look at who’s on the school bus. Look at who’s buying diapers in the grocery store.’ These statements were not made to the African American tester.

“While both testers were provided home listings in predominantly white areas, some of the statements made by the agent suggest that the agent is not interested in taking buyers to racially diverse neighborhoods.”

Newsday notified Marando of its findings by letter and email, invited her to view recordings of meetings with testers and requested an interview. She did not return phone messages.

Newsday presented its findings by letter to Charlie Young, president and chief executive officer of Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage. The letter covered the actions of Marando and additional Coldwell Banker agents.

The company’s national director of public relations, Roni Boyles, wrote in an emailed statement:

“Incidents reported by Newsday that are alleged to have occurred more than two years ago are completely contrary to our long term commitment and dedication to supporting and maintaining all aspects of fair and equitable housing.

“Upholding the Fair Housing Act remains one of our highest priorities, and we expect the same level of commitment of the more than 750 independent real estate salespersons who chose to affiliate with Coldwell Banker Residential Brokerage on Long Island. We take this matter seriously and have addressed the alleged incidents with the salespersons.”

Coldwell Banker declined to discuss the company’s responses to specific cases.

A map of the 5,763 house listings gathered by Newsday represents the collective choices made by the tested agents. All things being equal, white and minority listings should appear in roughly 50-50 proportions across the Island.

They did not.

The map revealed divided racial and ethnic patterns that would help shape both lives and communities, in some cases speeding demographic change and in others blocking it.

Most stark: Agents directed white buyers most heavily to areas with the highest white concentrations while most often suggesting that black buyers focus on areas with lower white representations.

“They’re putting you in a place that they think you belong. They’re telling you that you don’t belong on this side of town because of your race or whatever and it’s not right,” said black tester Johnnie Mae Alston, a retired state worker, adding:

“But just because you think I would rather be here or because I’m a certain race you think that I should be over here. But what about my choices of where I want to live?”

Both blatant and widely accepted before the civil rights revolution, racial steering by real estate agents has receded largely from view.

Where agents once openly shut black buyers out of white communities, some now apply courteous professionalism while sorting buyers based on race or ethnicity.

“The issue of discrimination is very subtle,” said Claudia Aranda, a director of field operations for the Urban Institute, a nonprofit group that oversaw more than 8,000 paired tests in a nationwide study sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2010.

That study found real estate agents engaged less frequently than in the past in more explicit forms of discrimination, such as not showing available houses to minority buyers. However, the study also showed that agents placed minority buyers in more integrated neighborhoods at a higher rate than white buyers.

“In the absence of treatment that’s more overt, in the absence of particular discriminatory comments, individual home seekers will never have potentially any reason to suspect discrimination,” Aranda said.

Newsday’s tests sought to get behind the smiles and handshakes that can mask evidence of steering by comparing how agents responded to paired buyers while video recorders were running.

Working one-on-one with an agent, an individual house hunter generally would never know whether the agent has suggested different options to other buyers, let alone determine whether the differences were based on race or ethnicity.

Evidence can emerge if an agent advises one or both testers about the racial or ethnic makeup of a community.

Century 21 agent Muhammad Chowdhry, for example, counseled a white tester about the advisability of searching for homes near the Nassau border with Queens, where some communities have significant immigrant populations.

“Mixed neighborhood like Guyana, you know, and, you know, from the island people. There are mixed people, you know?” Chowdhry said, adding, “So, you see, the closer you get to the city you have a subway and buses so other people that’s coming into the area, you know, the safety factor, it’ll go down.”

Chowdhry provided comparable listings to black and white testers. Still, based on the statements, Newsday fair housing consultant Robert Schwemm, a University of Kentucky College of Law fair housing law professor, concluded:

“The conversation with the white ‘customer’ is concerning, particularly when not given to the black tester. The ‘mixed neighborhoods like Guyana’ might have a claim against this agent for steering all customers away.”

Newsday’s second fair housing consultant, Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, found:

“The agent made inappropriate and discriminatory statements to the white tester.

“While the agent provided both the African American and white tester with listings in similar areas, the agent cautioned the white tester to stay further away from New York City (Queens) due to the race/national origin of the people in that area. The agent implied that the presence of a ‘mixed neighborhood like Guyana’ raised a ‘safety factor.'”

In many cases, the locations of listings provided to each tester can be key to judging whether an agent appears to have engaged in steering – or has properly recommended houses in different neighborhoods based on information provided by one tester and not the other.

Ideally, an agent will suggest homes in similar places to customers who are conducting similar searches, offer comparable qualifications and are matched except for race or ethnicity.

Consider, for example, how Realty Connect USA agent Vivian Kamath provided listings to a white and a Hispanic buyer when each sought help finding $400,000 homes within 30 minutes of West Islip.

Kamath, who declined an interview request, placed the choices for both testers – 23 for the Hispanic, 18 for the white – wholly in West Islip.

Kamath provided parallel listings to the white and Hispanic testers in the same community. In this case, the community happened to be 89 percent white.

When an agent provides similar listingsRealty Connect USA agent Vivian Kamath concentrated the choices for the white and Hispanic testers in a community that was 89 percent white.

Now, consider how Realty Connect USA agent Joseph Jannace recommended homes when black and white testers requested $400,000 homes within 30 minutes of Bay Shore, a community that neighbors West Islip but has a 38 percent white population.

Jannace’s choices stretched more than 40 miles from west to east. He placed only the white tester in the overwhelmingly white communities of North Bellmore, Seaford, Massapequa and Commack, and located only the black tester in largely minority Amityville, Copiague and Bay Shore.

The agent picked census tracts that averaged 67 percent white for the white tester and 58 percent white for the black tester.

When listings provide evidence of disparate treatmentRealty Connect USA agent Joseph Jannace picked census tracts that averaged 67 percent white for the white tester and 58 percent white for the black tester.

“The apparent steering is particularly evidenced by the white tester’s getting no listings in Amityville and getting lots of listings in west/white areas where the black tester did not,” wrote fair housing consultant Schwemm based on Newsday’s data.

In May, Jannace viewed Newsday’s video recordings of his meetings with the testers and was shown maps of the listings he suggested. In June, he declined to comment.

Newsday presented its findings by letter to Kevin McClarnon, listed as chairman on the Realty Connect website, and to Michael Ardolino, Fern Karhu and Bert Cafarella, listed there as owner-brokers. None responded to the letters or follow-up phone calls.

Agents are not required to give precisely identical listings to house hunters who have embarked on similar searches. Differences begin gelling into evidence of steering when an agent has placed two sets of listings in distinctly different locations that diverge racially or ethnically, experts say.

For example: An agent selects listings for a white customer in one town with a high white population level and chooses a second more integrated community for a minority customer.

Hispanic tester

Sent to more diverse Hicksville

White tester

Sent to mostly white BethpageHispanic and white testers, Liza Colpa and Lizzy Lee, asked Century 21 agent Palma Napolitano Reyhing for help finding $500,000 houses within 30 minutes of Bethpage. Lee said that her husband had taken a job at St. Joseph’s Hospital, a local medical center. Colpa said her mother lived in a Bethpage apartment.

Reyhing limited white tester Lee’s listings to Bethpage, a community that was 86 percent white. She offered Lee 13 home choices there, compared with three selections for Hispanic tester Colpa.

She instead focused Colpa on neighboring Hicksville, where the population was 57 percent white and 16 percent Hispanic. She gave Colpa eight listings to consider in Hicksville, compared with zero for Lee.

St. Joseph’s Hospital, where the white tester’s husband was said to work, and the street on which the Hispanic tester’s mother purportedly lived were roughly 1.5 miles apart in southern Bethpage. Reyhing concentrated the white tester’s listings in the area surrounding the hospital. She focused only the Hispanic tester’s listings to the north of Bethpage in Hicksville, as much as four miles from the location given for the mother’s residence.

Overall, Reyhing placed the white tester’s choices in census tracts that averaged 84 percent white, while the tracts selected for the Hispanic tester averaged 65 percent white.

“Steering seems clear,” concluded Newsday consultant Schwemm, citing the divergent demographics of the listing locations. Based on the same data provided by Newsday, fellow consultant Fred Freiberg wrote, “The locations of the listings selected by the agent raises a concern about possible steering.”

Notified that the test had “suggested evidence of steering,” Reyhing viewed Newsday’s video recordings of her meetings with the testers, as well as the maps of the listings she provided.

“I feel that your findings are totally unfair,” she wrote in an emailed response, also stating, “I am adamantly denying” steering.

She stated: “I do not look up the demographics for these towns or any other towns,” adding that she started both house searches in Bethpage.

Explaining her selections for the white tester, Reyhing wrote that “it made sense to start her off with just the Bethpage area” because of the location of her husband’s workplace.

Reyhing also stated that the tester “seemed confused and needed clarification on the different styles of homes;” was “overwhelmed” by possibilities that Reyhing had called up on her office computer; and said that she had “explained I would share more once she digested the current options.”

Referring to the Hispanic tester, Reyhing similarly wrote, “I did not want to overwhelm her with too many listings to look at.” She stated, “I did not have as much time to spend with her,” and added that she conveyed to the tester, “If need be, in time, we could extend to other areas within the time distance she wanted (30 minutes).”

The transcript of Reyhing’s meeting with the Hispanic tester shows that she said: “Maybe we’ll just do Bethpage and Hicksville, and we’ll start with that … And then we’ll do Farmingdale. I’ll add that on next week.” Farmingdale was 75 percent white with a 13 percent share of Hispanic residents.

Newsday presented the test findings to Century 21 Real Estate LLC president and chief executive officer Michael Miedler by letter. He did not respond to the letter or a follow-up telephone call.

Black tester

Sent to more diverse East Meadow and Hicksville

White tester

Greater opportunities in mostly white Bethpage and LevittownBlack tester Martine Hackett and white tester Kimberly Larkin-Battista consulted Douglas Elliman Real Estate agent Lisa Casabona for assistance in searching for $500,000 homes in the Bethpage area. Hackett said her husband worked at the Northrop Grumman defense company, a major employer in the community. Larkin-Battista said her mother lived in an apartment there.

Casabona recommended 26 houses to Larkin-Battista in neighborhoods that averaged 80 percent white, compared with 12 homes for Hackett in areas that were 74 percent white. The racial gap was driven by three factors:

- Casabona suggested 18 listings in 79 percent white Levittown to Larkin-Battista, and three in Levittown to Hackett.

- She offered six homes in 89 percent white Bethpage to Larkin-Battista and two to Hackett.

- She placed a total of six listings, only for Hackett, in East Meadow (69 percent white) and Hicksville (57 percent white).

Based on results provided by Newsday, fair housing consultant Fred Freiberg, executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, concluded:

“While the agent selected home listings for both testers in predominantly white areas, only the African American tester received listings in the more racially diverse communities of East Meadow and Hicksville, raising concerns about possible steering.”

Newsday’s second consultant, Schwemm, wrote:

“Different listings given to the two testers is evidence of both steering and differential treatment.”

He cited the differences in listings provided to the white and Hispanic testers in Bethpage (8 to 3) and in Levittown (18 to 3).

“Both towns have higher proportions of white residents,” Schwemm concluded. “Even if the agent wanted to keep the white tester closer to her mother’s residence, this doesn’t explain why the agent failed to give the minority tester similar access to Bethpage and Levittown.”

Strenuously defending her commitment to fair housing, Casabona said of the white tester: “The way that I interpreted it is that the woman wanted to be near her mother.” She added, “So to be near my mother meant I could walk to my mother to take care of her.”

Casabona also said that a five-mile commute to work would be reasonable for the black tester.

“I didn’t say to somebody go live in some terrible town far away,” Casabona said in an August telephone interview. She pointed to her own neighborhood in Levittown, near the border of Hicksville, where she said she had neighbors of various races and ethnicities. She said that she had served as a broker to a number of them.

“I sold my whole neighborhood to every ethnicity with no judgment, no discrimination to anybody,” she said.

Representing both Casabona and the Douglas Elliman company, an attorney with the Kasowitz Benson Torres LLP law firm watched the video recordings of the agent’s meetings with testers and reviewed listings maps. Firm partner Jessica Rosenberg presented a reason why Casabona did not suggest houses in Hicksville and East Meadow to the white tester:

“Ms. Casabona, correctly or not, believed that the black tester had more flexibility in terms of location” because “the black tester said her spouse worked at Grumman; the white tester said her mother lives in Bethpage.”

Rosenberg did not explain why those differences would influence flexibility in choosing a house location, nor did she address the imbalance between Casabona’s placement of white and black listings in Levittown.

Black tester

Sent to areas that averaged 66% white

White tester

Sent to areas that averaged 89% whiteThree months apart in 2017, black tester Ryan Sett and white tester Steven Makropoulos consulted Keller Williams Realty agent Suzanne Greenblatt about finding homes priced at up to $450,000 within an hour commute from Manhattan.

Greenblatt, who is based in Massapequa Park, suggested six houses to Makropoulos – all located in a cluster of overwhelmingly white South Shore communities made up of Bellmore, Wantagh, Seaford and Massapequa.

In contrast, her selections for Sett – 84 in all – stretched almost the entire east-west width of Nassau County, approaching the Suffolk County border in Massapequa Park on the east and nearing the New York City line in Valley Stream. North and south, the listings reached roughly 12 miles.

The communities Greenblatt recommended for Sett included some with the highest proportions of minority residents on the Island. Those included Westbury, Freeport, Baldwin and Elmont. As a result, the listings produced a 23 percentage point white-black gap between the areas selected for the two testers: Sett’s listings landed in census tracts that averaged 66 percent white while the tracts chosen for Makropoulos averaged 89 percent white.

Newsday fair housing consultant Freiberg found “possible racial steering,” writing: “The agent provided the white tester with home listings only in predominantly white areas while giving the African American tester home listings in surrounding areas, including many racially diverse and predominantly minority areas.”

After viewing video recordings of her meetings with the testers and reviewing where she suggested listings to each tester, Greenblatt said that the white tester “did not seem like a serious buyer” so “I just sent the most recent listings with the higher probability being available and that’s all that we had agreed to.” She said of the black buyer, “We had conversations that led me to believe he was a serious buyer.”

Greenblatt said she compiled the listings for the black tester by inserting home search criteria into the Multiple Listing Service of Long Island computer system based on his price range for all of Nassau County. Asked whether it was natural for the search to produce listings in the predominantly minority communities as well as some predominantly white areas, she responded that some towns have a larger number of “older-style houses.”

Schwemm concluded: “The predominance of black-only listings in the heaviest minority areas strongly suggests steering. In addition, the white tester could complain that the agent denied opportunities of living in more diverse areas.

“Also, those areas where the map shows black-only listings could sue for having their housing market racially impacted by this agent’s behavior.”

Asked for comment about the actions of Keller Williams agents, including Greenblatt, chief executive officer Gary Keller responded through the firm’s national spokesman, Darryl Frost, who said in an emailed statement:

“Keller Williams does not tolerate discrimination of any kind. All complaints of less than exemplary conduct are addressed and resolved in partnership with our leaders to ensure compliance with our policies, as well as with local, state and federal laws.

“In addition, we require all Keller Williams agents to take the National Association of Realtors Code of Ethics training, developed in accordance with the Fair Housing Act, before they earn their Realtor’s license and thereafter, every two years to maintain it. Every Keller Williams franchise also receives extensive industry training and resources that reinforce best practices in fair housing.”

Hispanic tester

Sent only to more diverse East Meadow

White tester

Sent to six communities, four mostly whiteHispanic and white testers, Ashley Creary and Lizzy Lee, asked RE/MAX agent Christopher Hubbard for help finding $450,000 houses within 30 minutes of Hempstead.

Hubbard advised white tester Lee that Hempstead, Uniondale, Roosevelt, Baldwin, Freeport and Elmont were either poorly rated or “not as nice.” Their populations ranged from 63 percent to 99 percent minority.

He recommended that Lee focus instead on Merrick, Bellmore and Wantagh, as well as possibly Seaford and Massapequa. There, the populations ranged from 87 percent to 91 percent white. He also suggested East Meadow, which was 69 percent white.

In contrast, Hubbard told Hispanic tester Creary that she “can maybe do” largely minority Baldwin or Uniondale, while adding that the schools in the two communities were not as highly rated as the schools in East Meadow.

Speaking about another of the predominantly minority communities, he shifted from telling white tester Lee that Elmont was “not as nice” to advising minority tester Creary, “Elmont, you know, it’s – it’s OK. It’s good.” He added, “But the school district is maybe not as prime as some other towns.”

Hubbard selected 14 listings for Hispanic tester Creary, all of them in 69 percent white East Meadow. He placed two listings for white tester Lee in East Meadow and gave her the additional opportunity to consider four houses in overwhelmingly white North Merrick, North Bellmore, Seaford and Levittown, plus 57 percent white Hicksville.

Overall, the tracts chosen for the white tester averaged 73 percent white, while the tracts selected for the Hispanic tester averaged 70 percent white.

“I don’t think he really gave me much of an option,” Creary said, adding, “I think they’re nice towns. I was brought up in Elmont so, I don’t know, that kind of hurts my feelings.”

Her eyes welling with tears, Creary concluded: “I didn’t think this would make me sad … People just judge you.”

Hubbard said that he relied on a website that purports to ascribe “livability” indexes to communities based on factors including crime levels.

He said he felt justified in calling Elmont “not as nice” because the website, areavibes.com, graded the community as C-plus in crime while grading East Meadow B-plus. At the same time, he felt justified calling Elmont “OK” and “good” because C-plus was a better grade than given to other areas.

A look behind areavibes.com’s grades revealed that the website based them on no official crime data for the communities. Since FBI and local law enforcement data were not available, the site used factors such as median income and home prices to estimate crime levels, the site’s founder, Jon Russo, said in an email.

Its projections proved inaccurate by a wide margin.

Areavibes.com ascribed crime rates to both Elmont and East Meadow that were roughly three times higher than they actually are, according to Nassau County Police Department statistics.

Similarly sized at roughly 37,000 people, the two communities experienced an average of fewer than one violent crime per week in 2018 – Elmont totaling 44 and East Meadow 37, including crimes such as assaults and robberies.

In the same period, Elmont reported 181 property crimes and East Meadow 123. Those included thefts, stolen vehicles and burglaries.

The two communities had different patterns of crime last year, county figures show. Elmont had 18 reported felony assaults and East Meadow had 28. There were 21 robberies in Elmont and five in East Meadow. One rape and two cases of sexual abuse were reported in each community. There were two murders in Elmont and one in East Meadow.

Property crime patterns varied last year, too. There were 119 reported grand larcenies in Elmont and 72 in East Meadow. Elmont had 35 burglaries and East Meadow had 43. Vehicle thefts were reported 27 times in Elmont and eight times in East Meadow.

Overall, the combined property and violent crime rates were lower in both communities than in Nassau County as a whole, county crime figures show.

Similarly, both communities had per-capita rates of violent and property crime that were substantially lower than the rates for New York State and the nation as a whole – roughly one-third to one-fifth the state and national rates, a comparison of county and FBI crime statistics shows.

Asked why he located the Hispanic tester’s listings exclusively in East Meadow while offering the white tester houses in Levittown, Seaford, North Bellmore and North Merrick, Hubbard sent a written explanation stating that he scattered the white tester’s listings to allow the tester to view a variety of house styles and citing the fact that the white tester would be commuting into Queens.

Referring to the Hispanic tester, he wrote that he chose homes in East Meadow to allow her to look at house styles there as a start and “would review every town that may be an option” after determining the tester’s interests.

While noting that the tester and her husband would be commuting into Queens and the city, he raised the possibility of exploring some of the same communities he selected for the white tester: North Merrick, North Bellmore, and Levittown. He also placed the listings for both testers in adjoining communities, as little as five- to eight-minute drives apart.

The vice president of communications for Hubbard’s parent company, RE/MAX LLC, provided a statement covering three tests of the firm’s agents, including Hubbard:

“We have spoken with the franchise owners whose agents were included in the inquiry and are confident that they have taken this matter seriously and are committed to following the law and promoting levels of honesty, inclusivity and professionalism in real estate.”

The spokeswoman, Kerry McGovern, declined to provide further information.

Based on Newsday’s data, fair-housing consultants Freiberg and Schwemm independently described the test results as showing the earmarks of a “classic example of steering.” They cited both the locations of the listings and Hubbard’s “exact opposite statements to testers based on their race and about the quality of neighborhoods.”

Black tester

Sent to areas that averaged 75% white

White tester

Sent to areas that averaged 83% whiteOn the same day in August 2016, Martine Hackett met separately with two real estate agents in Bridgehampton, a mainstay community in Long Island’s fabled Hamptons.

One agent worked for The Corcoran Group, the other for Douglas Elliman Real Estate at the time of the tests. Their offices were roughly one mile apart.

Hackett, who is black, told each agent that she and her husband had a school-age child and hoped to purchase a house for a price of up to $2.5 million somewhere among the Hamptons’ many distinct communities.

She related to both agents that she had visited friends for several years in Springs, a community with small lot sizes that had become home both to artists and to working-class residents. Hackett also made clear that she wanted to explore the Hamptons generally.

Two months later, again on a single day, white tester Gretchen Olson Kopp individually asked the same agents – Kevin Geddie at Douglas Elliman and Frederick Wallenmaier at Corcoran – for help with a comparable search:

She and her husband had a school-age child and were in the market for a $2.5 million Hamptons house. She told them both that her mother-in-law was in a rehabilitation center in Southampton.

Same agents. Same home searches. Two different results.

Wallenmaier provided the black and white testers with listings in a broad swath of the Hamptons that stretched from Southampton to East Hampton, giving both testers choices in Southampton, Bridgehampton and Sag Harbor. They carried an average price of $2.7 million for the black tester and $2.5 million for the white tester.

After touting Sag Harbor schools, Wallenmaier recommended six listings there to the black tester and four to the white tester.

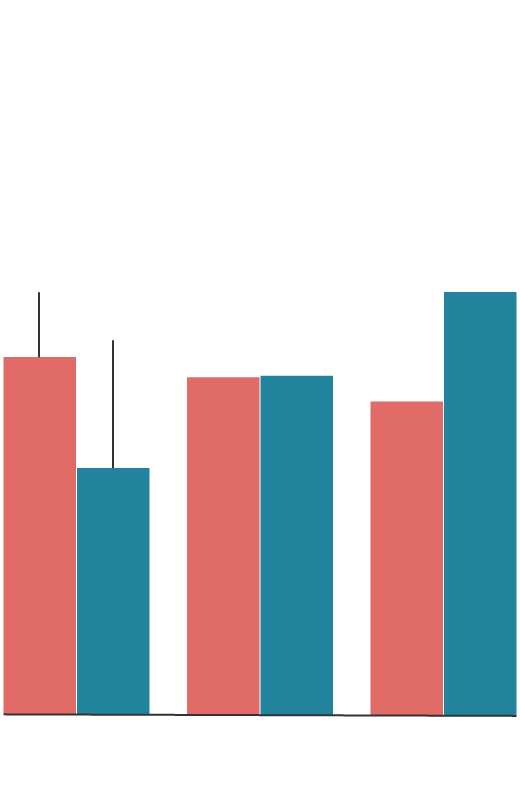

When an agent provides comparable listingsCorcoran agent Frederick Wallenmaier chose listings in census tracts that averaged exactly 78.2 percent white for each tester.

In contrast, Geddie offered listings to Olson Kopp and Hackett along lines that divided the Hamptons to the west for the white tester in Southampton, Water Mill and Sag Harbor and to the east for the black tester in East Hampton, Amagansett and Springs. The price tags averaged a million dollars less for the black tester: $2.4 million for the white, $1.4 million for the black.

Geddie, too, cited the quality of Sag Harbor schools.

He told the black tester: “They really do have one of the best rated elementary schools in the country.”

He told the white tester: “Sag Harbor Elementary is, you know, country known. People love it there.”

Geddie offered the white tester five choices in Sag Harbor and provided none to the black tester.

When an agent provides disparate listingsDouglas Elliman agent Kevin Geddie’s tracts were 83 percent white for the white tester and 75 percent white for the black tester.

While speaking with white tester Olson Kopp, Geddie described the ethnic makeup of Springs this way:

“What you see a lot more in East Hampton is the Hispanic community came in – and they really took over Springs in Northwest Woods area – which is great, because we have a lot more kids now – so their high school is drastically bigger than Southampton is.”

Talking with black tester Hackett about the same high school, Geddie said only:

“East Hampton is really, really – I don’t know how to say – it’s overpopulated, I feel like.”

In an email, Geddie described his statement about the Hispanic community as “out of context,” adding:

“I apologize for this remark and I look forward to continually improving in order to service all of my clients with respect.”

He said the statement “does not represent who I am as a person and does not reflect my professional commitment to treat everyone – clients, family, and friends – equally and with respect.”

Douglas Elliman lawyer Rosenberg wrote that Geddie’s remarks “are inconsistent with Douglas Elliman policies and applicable law, and are not tolerated. Had Douglas Elliman been informed of such remarks at the time they were made, Douglas Elliman would have taken immediate and appropriate corrective disciplinary action.”

Geddie left Douglas Elliman and began working with the Compass real estate agency in January 2018. He attributed the differences in the locations of the listings he provided to the black and white testers to reductions in the number of homes in the marketplace between August and October, adding, “Claiming discrimination under these circumstances is off base.”

Despite the difference in time frame, Wallenmaier more broadly distributed 27 listings to the black tester in August 2016 and 28 listings to the white tester in October 2016.

Drawing on data it purchases from the Multiple Listing Service of Long Island, the system by which agents can follow which homes are on and off the market, Zillow computed that the number of houses available in the requested price range differed by less than 2 percent on the dates Geddie was tested.

“It comes out I wanted to give my potential buyer a more diverse look and background of the Hamptons and what they like, based off of the area,” said Wallenmaier, who is now an agent with Nest Seekers.

After reviewing Geddie’s interactions with Hackett and Olson Kopp, Freiberg cited Geddie’s comments “about Hispanics having taken over one area;” recommendation of houses in that area only to Hackett; and the fact that he provided listings only to Olson Kopp in Sag Harbor and Southampton after praising the schools.

“The agent’s conduct indicates differential treatment and steering,” Frieberg wrote.

Schwemm concluded: “The different placement of the listings provided to the two testers is evidence of steering and would indicate a need to retest the agent” if legal action was contemplated.

Watch videos of the testsSelecting Houses, Shaping Communities

The drive from Uniondale into East Meadow into Levittown is a six-mile journey through three worlds: one minority, one integrated, one largely white. It can illustrate how the individual actions of real estate agents can play roles in the composition of communities.

Some Long Island real estate agents tested by Newsday provided listings that followed the color line along the route.

Hempstead Turnpike ties the three Nassau County communities. Traveling west to east on the busy road, the makeup of the populations changes with abrupt increases in white representations: Uniondale, 21 percent white; East Meadow, 69 percent white; Levittown, 79 percent white.

Traveling the same route, agents chose virtually no homes for any potential buyers in Uniondale; split East Meadow listings roughly half-and-half between white and minority house hunters; and gave 80 percent of their Levittown listings to white customers.

The parallels between the makeups of the populations and the makeups of the house listings in the three neighboring communities offer a particularly vivid illustration of how race and ethnicity often correlated with the choices agents made for buyers of different backgrounds.

Uniondale joined Roosevelt, Freeport and Hempstead in a cluster of overwhelmingly minority western Nassau areas that agents avoided almost entirely, in effect steering away potential buyers of all races and ethnicities.

The four communities have a combined population of 147,000 people and range from 76 percent minority to 99 percent minority. Based on Newsday’s test zones, agents had 142 opportunities to choose houses for customers there.

Only four agents made such choices, providing a total of 44 listings in the four communities. A single agent serving an Asian customer provided all the listings gathered in Uniondale and Roosevelt (five each), as well as all but one of the listings provided in Hempstead (24).

In comparison, agents in 14 tests recommended 199 listings in East Meadow, while agents in 11 tests suggested 173 listings in Levittown.

Cumulatively, agents tested by Newsday kept their distance from Long Island’s overwhelmingly minority areas and focused instead on communities with higher than average white populations.

They recommended homes in census tracts where whites made up the majority of the population at twice the rate they did in tracts were minorities composed more than half the residents: almost 14 listings per tract where whites predominated compared with seven per tract where minorities were most prevalent.

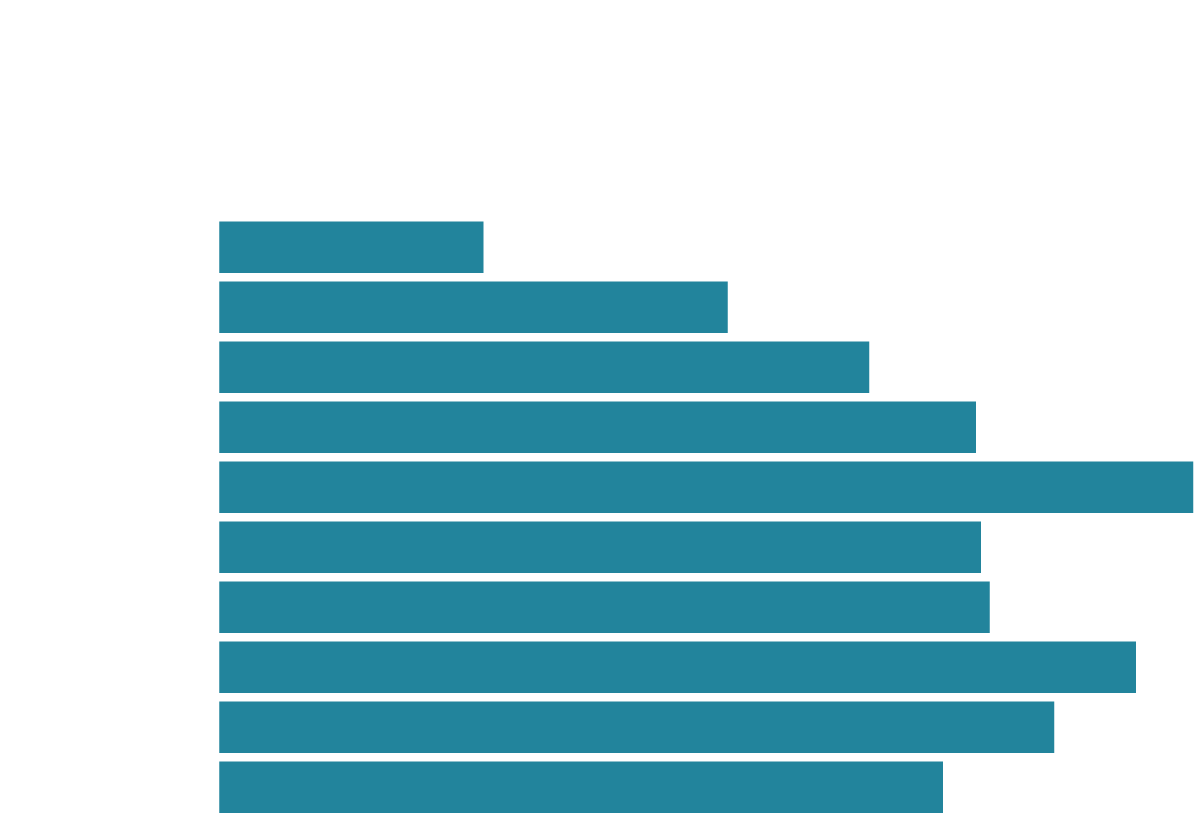

Agents gave the fewest listings in the least white census tracts

Each group represents one-tenth of Long Island’s census tracts — statistical boundaries with roughly equal-sized populations.

Census tract groups

Listings

212

0-20% white

20-52% white

409

52-65% white

523

65-72% white

609

72-77% white

784

77-82% white

613

82-85% white

620

85-89% white

738

672

89-91% white

91-100% white

583

Agents gave the fewest listings in the least white census tracts

Each group represents one-tenth of Long Island’s census tracts — statistical boundaries with roughly equal-sized populations.

Census tract groups

Listings

212

0-20% white

409

20-52% white

523

52-65% white

609

65-72% white

784

72-77% white

613

77-82% white

620

82-85% white

738

85-89% white

672

89-91% white

583

91-100% white

Overall, the agents chose houses for white potential buyers in tracts that averaged 78 percent white and minority house hunters in tracts that averaged 75 percent white.

That white-minority gap was narrowed by two factors: First, agents almost entirely avoided the predominantly minority communities that are home to Long Island’s largest concentrations of black and Hispanic residents. Second, some of Newsday’s test zones placed both white and minority house hunters in areas with overwhelmingly white populations.

At the same time, differences widened between the white and minority populations in neighborhoods selected by agents when predominantly white communities were located closer to more diverse areas. In those circumstances, the gap between white and minority populations on individual tests ran as high as 55 percentage points.

A comparison of the neighborhoods chosen for paired white and black buyers produced correlations between the race of testers and the racial composition of the recommended areas.

One-third of the 5,763 listings gathered by Newsday fell in census tracts that were less than 73 percent white, one-third in tracts that were 73 percent to 84 percent white and one-third in tracts that were 85 percent white or more.

What the numbers show- Where the white population was lowest, agents gave white testers their lowest share of listings (24 percent on average) and blacks their highest share (36 percent on average).

- Where the white population was highest, the count was reversed: White testers got the highest share of their listings (42 percent on average) and black testers got their lowest (31 percent on average).

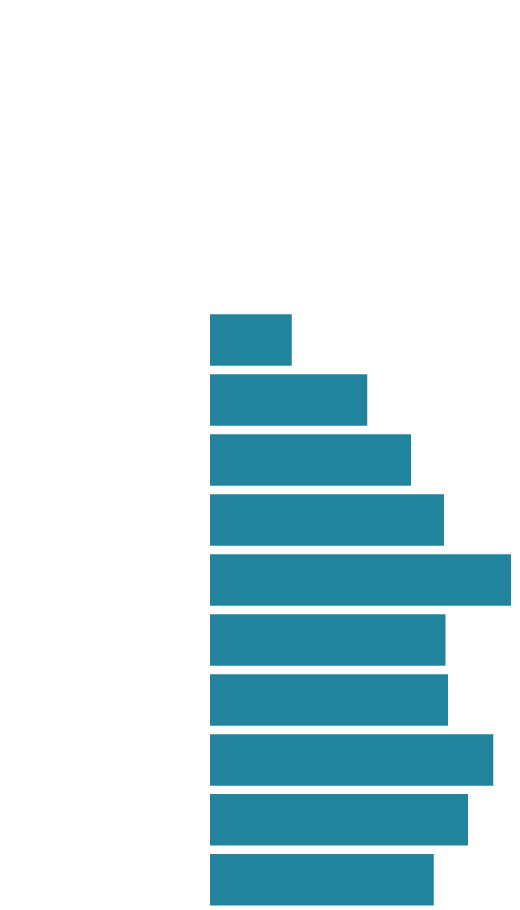

Average share of listings for black and white testers by census tract

Agents gave listings in comparatively high-minority areas to black testers more frequently on average than white testers.

Avg. black share

42%

Avg. white share

35%

33%

34%

31%

24%

0-73%

white tracts

73-85%

white tracts

85-100%

white tracts

The trends were different in the placement of listings provided to Asian and Hispanic testers compared with the listings provided to their white counterparts.

As happened with white testers, the agents gave Asian testers more of their listings in areas with higher proportions of white residents than they did in neighborhoods with fewer whites. The pattern was similar for Hispanic testers, although less pronounced.

Sources: Demographic data in maps and charts from Census Bureau 2016 American Community Survey five-year estimates.