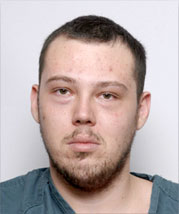

In 2013, Jack Franqui landed in a jail cell. He left in a body bag.

On Jan. 23, 2013, one of Long Island’s coldest nights in years, Jack Franqui shivered in a Suffolk County Police Department holding cell wearing only his socks and underwear, his bruised body soaked in toilet water. He had been ranting for hours that the cops had unfairly targeted him and that he planned to leave his cell in a body bag.

He fashioned a noose from a pair of bluejeans knotted to the bars of his cell. It was the third time in a matter of hours that Franqui — a 26-year-old man from Rocky Point booked on misdemeanor charges — had tied something to the bars. Officers on duty at the Seventh Precinct in Shirley had already confiscated a blanket and Franqui’s T-shirt in separate incidents. But officers ignored protocol and failed to put Franqui under closer supervision or transport him to a hospital.

A medical examiner would later state that it takes roughly ten minutes for somebody to die by hanging the way Franqui did. During that time, the only other prisoner in the cellblock said he faced a surveillance camera, made frantic gestures toward Franqui’s cell and screamed for officers to come save the dying man.

When nobody came, he gave up. He heard gasping, bones cracking and then silence.

An officer eventually noticed Franqui’s dangling body on a closed-circuit monitor.

“What is this guy doing now?” the officer, Joseph Simeone, remarked.

Franqui’s body was cold to the touch by the time officers made it to the cellblock. Deciding there was no point in trying to resuscitate him, officers left Franqui’s body hanging in his makeshift noose.

The homicide detectives who arrived soon after began to piece together what had gone wrong. The officers on duty kept records documenting prisoner checks that may not have actually occurred. The officers failed to act not only after Franqui had tied two items to the bars, but also despite obvious signs of erratic behavior witnessed by the other prisoner including banging his head repeatedly against the wall, drenching himself in toilet water and begging to be taken to the hospital.

Detectives found that an intercom system that pipes in sound from the cellblock to where officers were stationed 70 feet away had been switched off. And officers had turned up the volume on a TV they were watching loud enough to drown out the other prisoner’s screams for help.

Suffolk County’s law enforcement officials did not tell the public this story of failure and neglect. Instead, the department contradicted its own internal documents in saying that Franqui was calm, at ease and showed “no indication” that he was suicidal before he took officers by surprise and suddenly killed himself.

Franqui’s family got the same story, and for months, they had no choice but to assume it was the truth.

There’s an increasing burden on police officers to deal with mental health issues requiring a law enforcement response. Suffolk officers transported 4,273 people, most of them involuntarily, to a psychiatric ward in 2014. The number has risen steadily every year since 2008, when Suffolk officers transported 2,524 people for psychiatric care.

SCPD cadets receive hours of training on how to handle encounters with the mentally ill, and the department’s rules and procedures call for “compassionate, safe and effective handling” of those dealing with “possible mental/emotional issues.”

“You’re dealing with good people, but they’re suffering from this illness,” said SCPD Sgt. Colleen Cooney, speaking in general and not about Jack Franqui. “And the officer has to realize that they may not be behaving in their best way because they’re dealing with this illness, which might make them dangerous to themselves or others.”

Before Franqui’s clash with local law enforcement in December 2011, he led what was on the surface an unremarkable life. After attending Rocky Point High, he lived in a rented 720-square-foot, cream-colored duplex on Xylo Road, drove a Honda and owned a dog named Dog.

Franqui’s friends said he liked to unwind after work by playing Xbox while smoking marijuana. He worked as a chef at the American Red Cross, where he cooked meals for the elderly. After his death, some of the older women who worked with him there would take the time to write remembrances of the goofy, lanky young man who called them “Auntie” and was famous for his “egg in a boat breakfasts.”

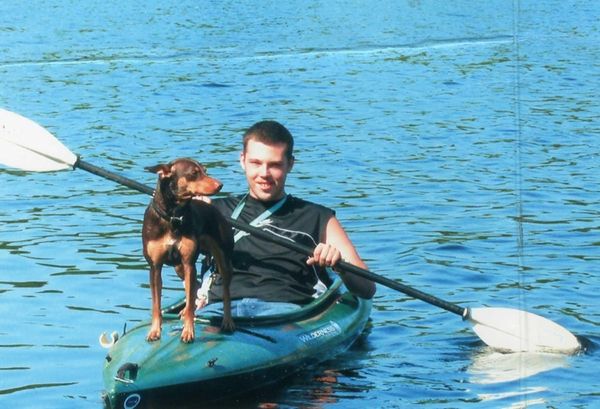

An only child whose parents had divorced when he was a teenager, Franqui spent time on the nearby Long Island Sound, kayaking or puttering on a 12-foot motorboat owned by his father, Joaquin Franqui, who like five generations of men dating back to Spanish roots also goes by Jack.

“He was my fishing buddy,” the elder Franqui, a facilities manager at Stony Brook University, said of his son. “He was my constant companion. We did everything together.”

When he learned that Franqui had killed himself in a precinct holding cell, he recalled an incident from when his son was 17. One day his son came home with a puncture wound to his stomach and told his father that some guys had jumped him. But the elder Franqui always suspected the wound was self-inflicted.

Kristy Repp, Franqui’s onetime girlfriend, said he had untreated mental problems and had threatened suicide “at least five or six” times when she attempted to break up with him.

“Anybody who’s taken Psych 101 would tell you that he was bipolar,” Repp said.

Repp said she finally decided to call the authorities on the morning of Dec. 1, 2011. She was with Franqui at his home as he threatened suicide while “loading a shotgun and putting it into his mouth.”

Repp said she expected an ambulance. “I didn’t expect the police force to show up like he had just robbed the bank,” Repp said.

Officers flooded a narrow Rocky Point road before noon on a Thursday, making for a chaotic scene and perhaps explaining why officers later filed statements that were inconsistent on two key claims: whether Franqui stepped outside his house with a gun, and whether he fired it at an officer.

In charging documents, two officers at the scene attested that Franqui was outside his house brandishing a loaded .38 Special. However, a third officer alleged only that she witnessed Franqui announce that “he had a gun in his pocket” when he exited his house.

Repp said she watched the incident unfold from a nearby driveway, roughly 200 feet away. She denied that Franqui brought a gun outside, although that was ultimately the charge for which he would be convicted. She said Franqui stood in the middle of the street, unarmed and wearing only his boxer shorts, yelling at the officers.

Franqui then ran inside, and Repp said she watched through the ajar front door as Franqui grabbed a gun. Officers reported that as Franqui was “kicking and wrestling” with police Officer Douglas Libonati, he fractured the officer’s hand. Franqui was finally subdued, but not before he “shot a loaded firearm” at Officer Kevin Corrigan, according to complaints filed by two officers.

Repp disputed that, saying that after Franqui ran inside his house, he put a revolver to his own face as the officers surrounded him. “They kicked the door in and the gun shot off behind him and went in the ceiling,” Repp said.

Corrigan himself filed a report reinforcing the narrative that Franqui had taken a shot at him. In a criminal complaint, Corrigan stated that Franqui “fired a functioning handgun in close proximity and in the direction of your deponent [Corrigan] and striking the ceiling.”

Two of the officers who were at the scene of that 2011 arrest would be called to testify before grand jurors investigating Franqui’s 2013 suicide. They are not identified by name, but their testimony as to what happened that day, as summarized by a grand jury report, does not contradict Repp’s version of events.