Among Jack Franqui's last words was a plea: Tell my dad the real story of what happened today.

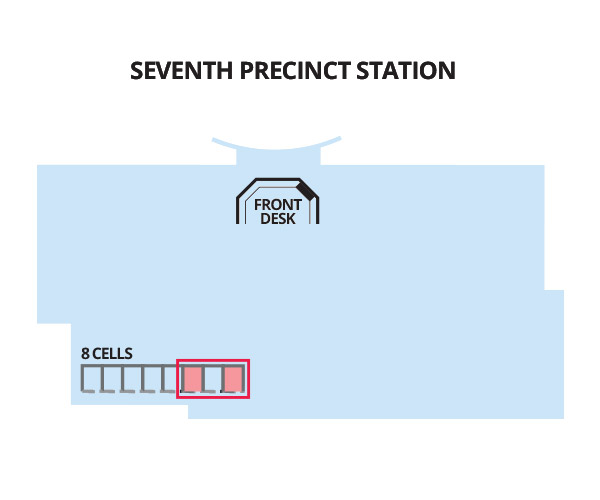

John Burke entered Male Cell #3 at the Suffolk County Police Department’s Seventh Precinct in Shirley on the afternoon of Jan. 23, 2013. There are eight units on the cellblock, each one 6-foot-1 across by 7-foot-9 long and furnished only with a metal sink-toilet and a wooden bench.

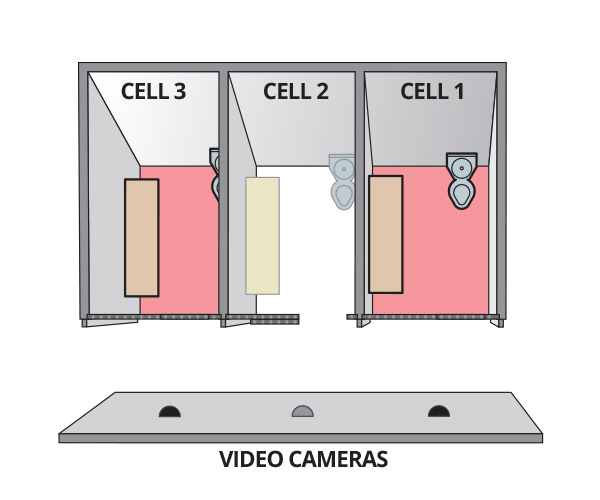

Through the bars and up near the ceiling, surveillance cameras eyed each cell. A tinted plastic shell protected each camera, and in its reflection Burke could see another prisoner locked up two doors away in Male Cell #1.

“I’m sorry you got arrested for whatever you got arrested for,” said the other prisoner, who introduced himself as Jack. “I’m kind of glad you did though, because now I have some company.”

Over the next few hours, Burke, 35, and Jack Franqui were the only prisoners on the precinct cell bock, typically an overnight way station for recently arrested people awaiting arraignment the next morning.

SCPD homicide detectives responded to the precinct shortly before 7 that night to investigate Jack Franqui’s suicide. A later homicide report identified five detectives as being a part of the investigation.

Among them were Charles Leser and Ronald Tavares, homicide veterans who have attracted legal scrutiny for their role in the alleged cover-up of a 2011 police shooting of unarmed cabdriver Thomas Moroughan in Huntington Station. They obtained from Moroughan a since-discredited statement that initially justified intoxicated off-duty Nassau County police Officer Anthony DiLeonardo’s decision to fire at Moroughan. At least one other homicide conviction has since been vacated because it hinged on Tavares’ detective work.

At the precinct, the homicide squad found the trio of officers who had been responsible for Franqui’s life.

Sgt. Kevin O’Reilly was the desk supervisor and the officer in charge of the precinct. He had worked the desk only once or twice before and had been promoted about two and a half weeks earlier. He had not yet completed the supervisory training required of every sergeant in the department.

The desk officers working under O’Reilly were George Oliva, who had been stationed at that desk about fifteen times, and Joseph Simeone, who had been stashed there for more than a decade after superiors deemed him “less than adequate” as a police officer. Simeone had health problems that limited him to light duty status and barred him from contact with prisoners.

When the officers found Franqui hanging in his cell wearing only white socks and camouflage underwear, O’Reilly told the detectives, the prisoner had no pulse and was “purple, blotchy and cold.” O’Reilly declared Franqui “gone” and in an effort to preserve the crime scene, had stopped Oliva from untying Franqui and attempting to resuscitate him. A state investigatory commission would later call O’Reilly’s decision to make no effort to save Franqui’s life a failure worthy of disciplinary action.

The detectives also spoke with Burke. The Brooklyn resident had been locked up that day on charges that he’d attempted to arrange to have sex with a 10-year-old girl by offering her mother $4,500 — a background that would typically make for an imperfect witness. But Burke ultimately testified under oath about Franqui’s death at least three times, including before a special grand jury, and the critical elements of his account have not been challenged. In fact, Burke’s story has been corroborated by evidence and the testimony of several police officers.

Burke also told his story with the belief that he would be backed by the perfect witness: The surveillance cameras trained on the cells.

“Again, the tape will show it all,” Burke said.

The homicide detectives would find, however, that the surveillance cameras at the precinct did not record any footage. The lack of a video record made Burke’s account vital to ascertaining what occurred.

Though Burke’s story would be echoed by officers when they testified under oath before a special grand jury, a homicide report filed a month after Franqui’s suicide presented a more sanitized version of what happened.

Burke repeatedly referred to Franqui making his T-shirt into a “noose,” and that officers advised Franqui to “stop doing stupid [expletive]” as they removed the shirt from the bars. Burke said Franqui’s request for medical attention was denied by an officer who said, “If we bring you to the hospital, we’ll just end up bringing you back here.”

In sworn testimony, Burke said Franqui repeatedly threatened to kill himself. “And he just kept on saying — like he was screaming to them, ‘If you don’t get me medical attention, I’m going to leave here in a body bag,’ ” Burke said. “I mean, he screamed that.”

The homicide report noted Burke’s claim that Franqui was ignored when he asked an officer for medical assistance. But the detectives did not report that Burke said the fellow prisoner was yelling suicidal threats for the guards to hear, only that he “mentioned” to Burke “that he was going to hang himself.”

The report shows O’Reilly told homicide detectives that Franqui tied his T-shirt to the bars in “an apparent attempt to obscure the vision of the surveillance camera,” not to make a noose, as Burke insisted.

When Franqui finally hung himself with his jeans and could be heard gasping for breath, Burke told the detectives he screamed for officers to come help until he realized it was a futile effort.

“It got to the point where I just gave up and I was just standing there just in shock,” Burke later testified. “Like I could hear his bones cracking and stuff, you know.”

There’s no way to know at what point Franqui still could have been saved. But at least three times that year, Suffolk County precinct officers noticed prisoners attempting to hang themselves with shirts tied to holding cell bars and reached them in time to rescue them. Burke, however, said it took roughly five to 10 minutes for officers to arrive — too late to save Franqui, as O’Reilly decided.

The homicide detectives learned how Burke’s screams could have gone unheard. Oliva acknowledged that the volume on a television they were watching made it “difficult to overhear sounds from the cellblock.”

In addition, detectives discovered that an intercom system installed to transmit sound from the cellblock to the precinct desk had been switched off, according to a grand jury report. The homicide squad’s own report, however, states that the intercom system was “operational and at a low volume setting.”

There were other key facts not found in the homicide report that would prove central to the grand jury investigation.

On the night of Franqui’s suicide, Det. Tavares obtained and reviewed phone recordings to and from the precinct. The homicide report does not note that the phone calls contained evidence that Simeone had withheld information from his supervisor, and then later from detectives, concerning yet another incident earlier in the day, when Franqui’s blanket was confiscated after he tied it to the bars of his cell.

The homicide squad also did not report that an inspection log showed that Simeone, who was responsible for checking on prisoners during that shift, did not make those checks as required.

In his own interview with the detectives, Simeone said “at no time did the prisoner indicate that he needed medical attention or that he was a threat to himself.”

Despite the evidence to the contrary, the police department’s public statements mirrored Simeone’s description of events. Then-homicide commander Det. Lt. John “Jack” Fitzpatrick, who signed his unit’s report detailing their investigation of the suicide, described Franqui as calm and at ease with officers before unexpectedly taking his own life.

“There was no indication he was suicidal,” Fitzpatrick said in a Newsday article published the morning after Franqui’s death.

Fitzpatrick retired last year and declined to comment for this article, citing the ongoing litigation.

Timeline of events

Jan. 2013: Franqui suicide

Jan. 2013: Franqui suicide

March 2013: Burke released from prison

March 2013: Burke released from prison

January 2014: Grand jury convened

See how it happened

January 2014: Grand jury convened

See how it happened

The only civilian eyewitness who could contradict the homicide commander’s account spent the next two months in Suffolk County jail cells.

Burke was released on March 22, 2013, after pleading guilty to charges that included a felony for disseminating indecent material to minors. He received a sentence of time served and immediately upon his release searched online for news about Franqui’s suicide.

He found the Newsday article containing what he called Fitzpatrick’s “ridiculous” characterization of Franqui’s calm demeanor before the suicide. “I was angered by that,” Burke said in sworn testimony.

On the day he was set free, Burke dialed the phone number Franqui had asked him to memorize. When Franqui’s father — who also goes by Jack — answered, Burke told him what happened and that “the reports in the news were false.”

Franqui’s family had received no information from law enforcement officials about the suicide other than what Fitzpatrick had said to the media. Burke told Franqui’s father, “I will be there to support you because your son seemed like a nice guy.”

“I got to know him for a couple hours,” Burke later testified. “And I just felt like what happened wasn’t right.”

After speaking with Burke, Franqui’s father hired Mineola attorney Anthony Grandinette. In a recent interview, Grandinette called the suicide in police custody the result of officers’ “catastrophic failure to follow their own rules and regulations” and criticized the homicide squad’s findings, which were “directly opposite” of what the evidence showed.

“That is not by mistake,” Grandinette said. “That is by design and it’s nothing short of fraud and corruption.”

In April 2013, Jack Franqui’s estate filed a notice of claim — a precursor to a lawsuit — against Suffolk County and its police department. The claim alleged that Suffolk officers violated Franqui’s civil rights when they falsely detained him, used excessive force during the arrest, ignored his suicidal actions and pleas for medical attention, and then covered up their failings.

“He would still be here today if we had people behind that desk who were willing to serve and protect,” Franqui’s father said. “They lied about it and hid the fact that they didn’t do their job.”

As Franqui’s family moved ahead with their lawsuit, a state commission that oversees correctional institutions criticized Suffolk County’s district attorney’s office and police department for mishandling a case similar to that of Franqui.

The state Commission of Correction found in a report released June 2013 that District Attorney Thomas Spota’s office had been negligent in failing to criminally investigate the homicide of Daniel McDonnell, a carpenter with mental and physical health problems who died in a 2011 struggle with officers at the First Precinct. Suffolk County ultimately paid $2.25 million to settle a wrongful death lawsuit filed by McDonnell’s family.

The commission found that officers conducted prisoner checks via security monitors rather than making required visits to the cellblock, ignored McDonnell’s screams for medical attention and failed to place him under one-on-one supervision despite his agitated state.

The commission report states that homicide detectives performed a “cursory and incomplete” investigation into the circumstances of McDonnell’s death, including the use of excessive force by officers.

The commission also determined the police department had “failed to conduct a comprehensive internal investigation” into McDonnell’s “preventable” death, the medical examiner’s office “failed to adequately identify and examine the blunt force injuries” to his body and Spota’s office “failed to conduct any investigation” of the death in custody even after it had been ruled a homicide.

Spota, in a defiant response written on June 27, 2013, called the commission’s report “baseless and inaccurate.”

Meanwhile, nearly six months had passed since Franqui’s death, and Spota’s office had not convened a grand jury to investigate the incident.

Franqui’s family filed its lawsuit in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District in Central Islip in late October 2013. In January 2014 — nearly a year after Franqui’s death — Spota convened a special grand jury to investigate the matter.

Pace Law School professor and former Manhattan prosecutor Bennett Gershman said it’s highly unusual for a district attorney to allow so much time to elapse before opening a grand jury probe.

“It’s incomprehensible that they would wait so long, especially if you’re talking about events that rely on people’s memories,” Gershman said.

Peter Davis, a recently retired professor at Touro Law Center who previously probed police misconduct as special counsel to a Suffolk County Legislature committee, agreed that the lag before convening the grand jury was unusual.

“The general rule is that a delay is bad for the district attorney’s case and good for criminal defendants,” Davis said. “You don’t want a delay if you can avoid it.”

During the nine-month special grand jury session, prosecutors called 24 witnesses and presented 45 exhibits of evidence, much of it materials that homicide investigators had access to on the night of the suicide.

The brunt of the blame would fall on Simeone, whose contentious history with the department is contained in a separate civil court case that was not noted in the grand jury report.

Simeone unsuccessfully sued the SCPD in 2000, claiming that he had been rejected for promotion to sergeant due to discrimination on the basis of disability and age.

The department countered that the rejection was based largely on a deputy inspector’s evaluation depicting Simeone as interested only in “the arena of future retirement planning.”

The evaluation stated that Simeone’s “performance began to deteriorate in 1988,” his seventh year on the job. In years since, a supervisor reported problems motivating Simeone, who “purportedly incurred a back injury” when he fell out of his chair at a police precinct in 1996. A year later, Simeone had a heart attack and was placed on permanent limited duty.

The deputy inspector’s evaluation concluded that the officer “seems to be lacking those qualities we expect of potential supervisors,” including “interest in one’s career, needs of the public, development of subordinates and attainment of Department goals and objectives.”

Though Simeone called the evaluation “untruthful,” he acknowledged under oath that he had difficulty with such physical activity as walking through a mall, washing his car, vacuuming a rug or traversing a flight of stairs. A phone call to his desk at the precinct once aggravated him so badly that he suffered an angina attack and had to call his wife to take him home, Simeone testified.

“My batteries run low and then I have to rest,” Simeone said in a deposition for his lawsuit, which was ultimately dismissed before trial. “After putting in an eight-hour day, I’m exhausted.”

Simeone’s limited duty status allowed him to carry a gun but not have any physical contact with suspects. Nevertheless, the department stationed him since 2000 at the Seventh Precinct front desk, where his duties included checking on prisoners in the cellblock.

Special grand jury testimony called into question whether Simeone had been making those checks. Simeone kept an activity log indicating that from 3 p.m. through 5 p.m. during Franqui’s time locked up, he had checked on him every half-hour, as required. However, the log showed no inspection until 5:40, when it is noted that Franqui’s T-shirt was confiscated.

The officer acknowledged during his special grand jury testimony that his log may have been inaccurate. “Simeone was reluctant to state during his testimony that the inspections were actually occurring at the recorded times,” a special grand jury report stated. “He admitted during his testimony that some of the inspections may not have occurred as written on the log.”

Though the homicide detectives did not note it in their report, their investigation uncovered recordings of two precinct phone calls in which Simeone could be heard speaking about a blanket that had also been confiscated from Franqui.

“He was tying the blanket,” Simeone said. “That’s why we don’t give them blankets. I don’t know why they give them blankets.” At another point he could be heard saying “tying a blanket . . . to the bars” and stating that “we took the blanket away from him.”

Simeone did not tell the homicide detectives about the blanket incident, which occurred before Burke was locked up in the cellblock. Simeone’s supervisor, O’Reilly, also said he had not been told about the blanket.

Simeone acknowledged to the grand jury that “anytime you see somebody doing something by the bars, that’s a red flag, you take a look.” But Simeone testified he did not believe confiscating Franqui’s blanket was a significant event of the sort that would merit action.

Sgt. O’Reilly disagreed, testifying before the special grand jury that if he had known about the blanket incident when officers later removed the T-shirt from Franqui’s cell, he would have put the prisoner under one-on-one supervision. “Franqui’s suicide would not have occurred and was preventable,” a special grand jury report stated.

The Commission on Correction, which completed its own report on Franqui’s death in September, agreed with the special grand jury’s findings but found that Simeone was not the only officer at fault. The commission also stated that O’Reilly’s failure to put Franqui under isolated supervision or send him to a hospital after the T-shirt incident was “a fatal mistake” that led to Franqui’s death.

Both Simeone and O’Reilly refused to answer questions when subpoenaed by the commission, invoking their Fifth Amendment right to not incriminate themselves.

Attorney Brian J. Davis, who represents O’Reilly, defended his client’s actions on the day of Franqui’s death by noting his inexperience as a supervisor.

“There were certain things procedurally that he had never been trained in,” Davis said in a recent interview, adding that the lack of training was “not his fault.”

Pace Law Professor Gershman reviewed special grand jury reports and other documents detailing Franqui’s suicide at Newsday’s request. The former prosecutor said criminal charges against Simeone and other officers could have included conspiracy, official misconduct, filing a false instrument, tampering with evidence, obstructing governmental administration and perjury.

Retired Touro Professor Davis, who also reviewed the documents, said that the officers involved “certainly” could have been charged with some of those crimes, comparing the Franqui situation to the ongoing prosecution of Baltimore police officers blamed for prisoner Freddie Gray’s death in custody.

But the grand jurors in Franqui’s case did not have the option to indict either Simeone or O’Reilly, because both received from district attorney Spota what is known as “transactional immunity.” In New York, if a grand jury witness is allowed to testify without waiving the right to automatic immunity, the witness is shielded from prosecution in the case.

A special grand jury report justified the decision to allow Simeone and O’Reilly to receive immunity because their “testimony was key to determining what occurred” and “in order to learn the truth, prosecutors were forced to give up the ability to criminally prosecute any police officer.”

Gershman said with other willing witnesses — such as Burke and Officer Oliva, who agreed to waive his right to immunity before testifying — “you don’t have to give immunity to any of these officers.”

State criminal justice statistics show that Suffolk County prosecutors are normally unencumbered by the transactional immunity law and are among the most successful in the state during typical grand jury proceedings. Between 2008 and 2014, Spota’s office won over 314 indictments to each “no bill” – meaning a proceeding that ended without an indictment due to insufficient evidence – in grand juries stemming from felony arrests. The statewide average in the same kind of cases over that span was just over seventeen indictments to every no bill.

Spota has also blamed the transactional immunity law for his inability to prosecute police in the special grand jury convened to investigate the cabdriver shooting in Huntington Station by intoxicated off-duty Nassau Officer DiLeonardo. Spota claimed in that case that his prosecutors could not proceed at all for fear of granting immunity to other officers at the scene of the shooting who may have broken the law.

Gershman noted that Spota’s handling of transactional immunity in the DiLeonardo and Franqui cases were at odds. But “in both cases it appears he’s protecting the police,” Gershman said.

The special grand jury that investigated Franqui’s death released two reports, one calling for Simeone to be disciplined and the other proposing recommendations for widespread reform to prevent another tragedy.

Among the 19 recommendations, grand jurors in the Franqui case called for the formation of a county task force to investigate ways in which Suffolk police can improve “prisoner safety, security, humane treatment and medical treatment” for detainees.

Grandinette, the Franqui family’s attorney, said that he relayed to the district attorney’s office a request from Franqui’s father that he be involved in the proposed task force inspired by his son’s death. Grandinette said he received no response.

The report also recommended that the police department improve screening so that officers are aware of an arrestee’s past suicidal or psychiatric behavior; that precincts employ “detention attendants” to “maintain close physical observation of prisoners”; that light-duty officers like Simeone not be permitted to perform prisoner inspections; that supervisors be ranked higher than sergeant in order to be in charge of a precinct; and that each desk have more than two officers and a supervisor per shift.

And the special grand jury reports called for all precinct video cameras to record and be positioned to monitor the officers as well as the prisoners.

Watch News 12’s Oct. 1 interview with Spota

Special grand jury reports are public records under New York State law, and Spota has touted many of those reports on his office’s website. But in the matter of Franqui’s suicide, he did not have the report posted and made no public announcement that an investigation had occurred. Spota would not make himself available for an interview with Newsday, which first contacted his office about this story in September.

Former Touro Professor Davis said he found the lack of promotion of the grand jury’s findings troubling considering the high expense and public importance of grand jury proceedings.

“The recommendations then need to be communicated to the people involved and they should be published to the general public as well,” Davis said. “If they don’t do that, then I’m not quite sure what the point is.”

At least one lawmaker who would be central to implementing the recommended reforms said although she knew of Franqui’s suicide, she had “heard nothing” about a probe being convened to investigate it.

Legis. Kate Browning (WF-Shirley), who is chair of the Suffolk County Public Safety Committee and whose district includes the Seventh Precinct, said she had not seen copies of the special grand jury reports until a Newsday reporter provided them in September.

“It’s a little disturbing when you call me about something and I don’t have that information,” Browning said.

The police department cited the ongoing litigation in denying Newsday an interview with any officials about the Franqui case, but said in an emailed statement that it “continues to implement and maintain the best police practices” in ensuring the safety of arrestees and had made changes in mental health screening, prisoner monitoring and training.

The grand jury reports also noted that some changes had already been implemented in the immediate wake of Franqui’s death. Steel doors to cellblocks are now operated by a key card that tracks which officer is checking on prisoners, and how often. And officers must now keep their precinct’s intercom in the “on” position so that a prisoner’s screams for help can be heard.

Although not requested by the grand jury, the officers’ television has been removed from the Seventh Precinct.

Court records show that Simeone was not interviewed by the department’s Internal Affairs Bureau until July 2014, nearly a year and a half after Franqui’s suicide.

The records reveal that administrative charges were filed against at least three officers: Simeone, Sgt. O’Reilly, and Lt. John McHugh, who oversaw the previous shift and booked Franqui. The records do not specify the charges against the officers or whether any discipline was administered.

O’Reilly’s attorney, Davis, said that his client had not been disciplined and that he did not expect any discipline to be meted out until the conclusion of the civil action by Franqui’s family.

The special grand jury recommended Simeone’s “removal or disciplinary action as prescribed by law.” In January 2015, Spota wrote in a letter to then-SCPD Commissioner Edward Webber that it was his “recommendation and hope” that the department fire Simeone and implement the special grand jury’s recommendations “so that another tragedy is prevented.”

Simeone, who earned $168,344 in 2014, has not been fired in connection with Franqui’s death. He has been transferred to the police department’s Yaphank-based property bureau, where he is responsible for evidence.