NFL Route Tree

Each movement by a wide receiver is carefully coordinated, and they all stem from one thing: the route tree.

The route tree is a simple way for an offense to teach, organize and quickly call plays. It was developed by Don Coryell while coaching at San Diego State in the 1960s. He brought it to the NFL in the 1970s as a head coach with the Cardinals and Chargers.

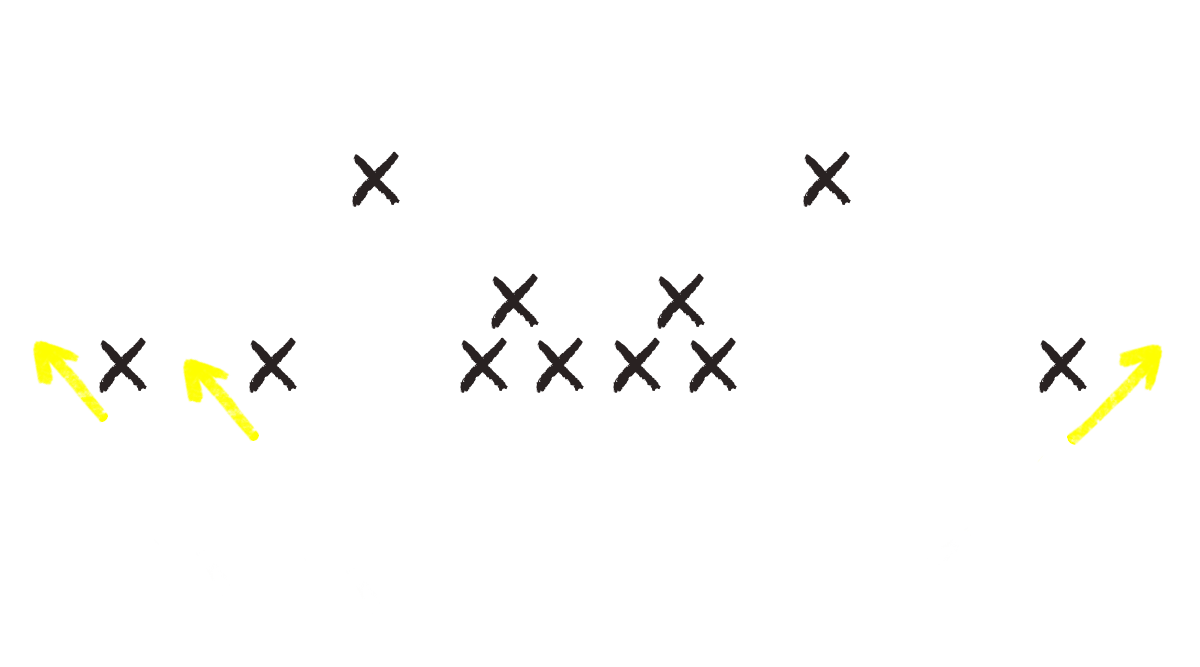

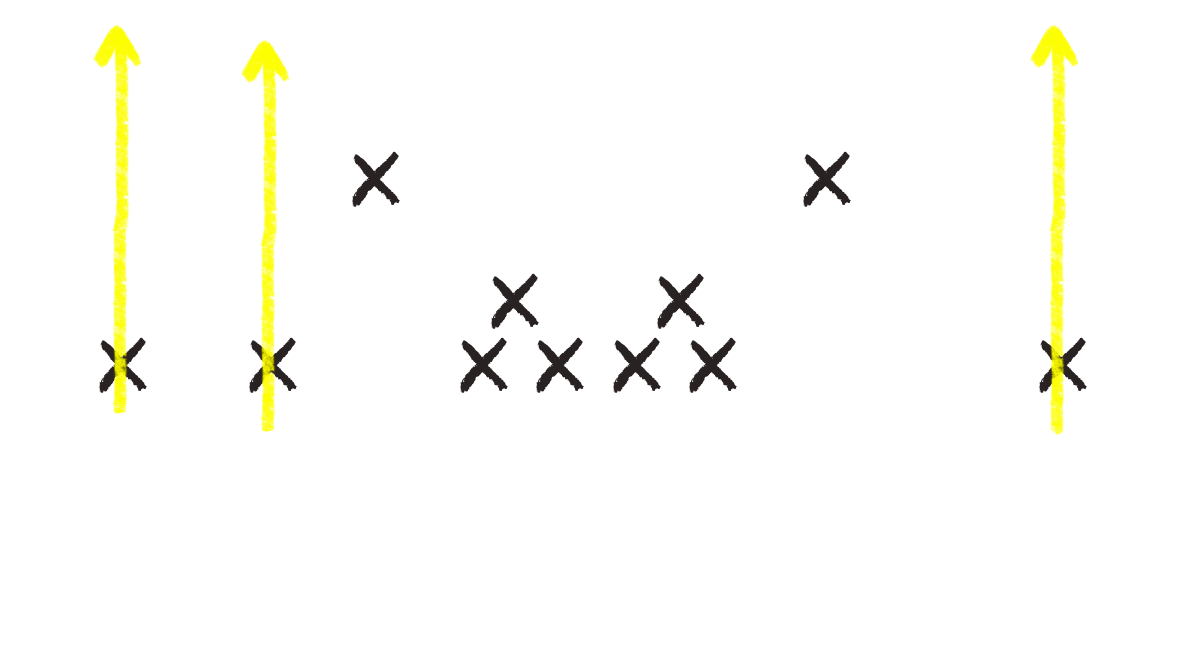

Odd-numbered routes break out to the sideline, even-numbered ones into the middle. An offense can use these numbers to quickly tell the receivers what routes to run on a play. For instance, a call that has the number “958” means that one receiver runs a “go” route (9), one runs an “out” route (5) and one runs a “post” route (8).

Click on each tab below to learn more about each route in the route tree, as well as the best players (active or retired) to run each pattern.

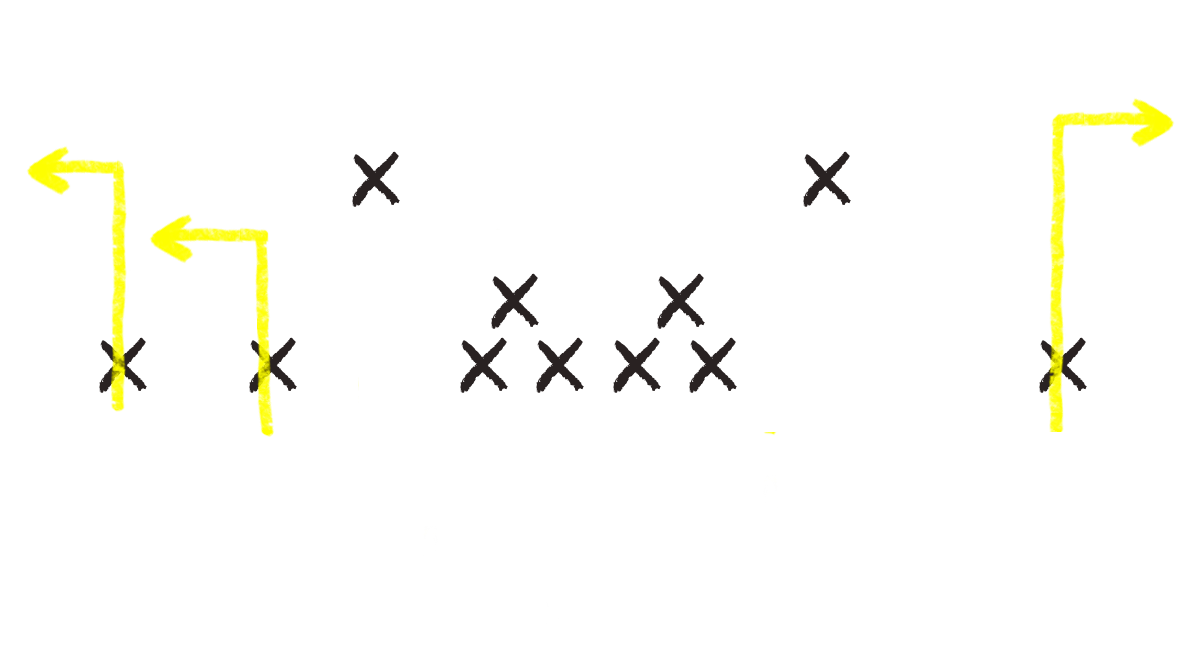

1 Flat

A flat is a short, quick-hitting route run close to the line of scrimmage. The receiver takes a step upfield, then quickly breaks out toward the sideline. It’s called a flat route because it’s run into the area between the sideline and the hash marks, known as the flat.

Usually, flat routes are run by running backs out of the backfield, tight ends and speedier, more elusive receivers, since the play’s result mostly will depend on what they can do after they make the catch.

Flat routes are effective when a defense commits to covering deep or as a checkdown option against heavy pressure. They’re also good when a team needs to quickly gain a few yards and stop the clock during a two-minute drill. In addition, flats often are paired with one or two other routes as part of a combo route — “stick,” “flood,” “spacing,” “curl-flat” and “slant-flat,” among others — designed to put stress on a specific defender and force him to choose who to cover.

Best to run the route: Roger Craig

2 Slant

A slant is the inside-breaking relative of the flat route (meaning, it’s a short, quick route close to the line). Here, a receiver takes three steps upfield, then cuts in at a 45-degree angle and runs toward the middle of the field.

Slant routes are good for speedier, shiftier receivers who can quickly shake defenders and do damage after the catch. Odell Beckham Jr. is a perfect example — he’s made a habit of turning 5-yard slants into 60-yard touchdowns.

Slants are good against a defense that is playing off coverage and giving the receiver a cushion, or against man coverage (since the receiver’s inside break should give him a step on his defender). An offense also can throw the slant route against a blitz-happy defense, since the quarterback doesn’t have to wait for his receiver to get far downfield and can get the ball out quickly.

Best to run the route: Beckham, Jerry Rice, Andre Reed, Art Monk

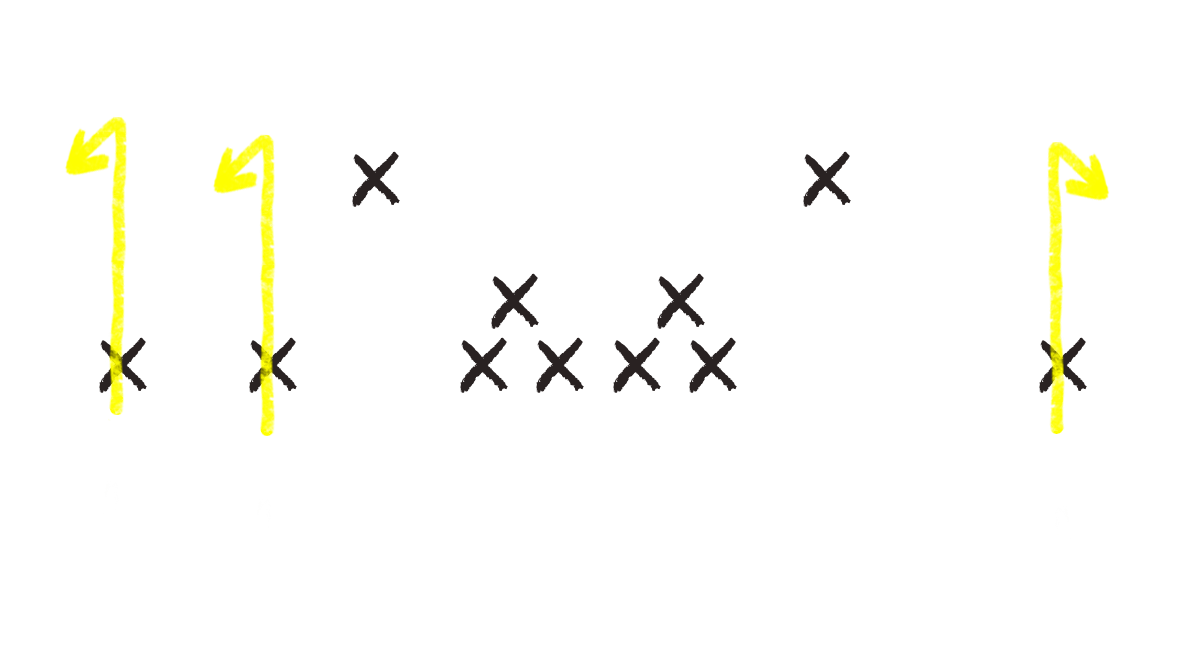

3 Comeback

A comeback is an intermediate route that usually covers about 10-15 yards. As soon as the receiver reaches the top of the route , he plants, turns out and runs back toward the sideline to make the reception.

The key part of a comeback route is the timing between the quarterback and the receiver. In an ideal situation, the ball should be at the receiver as soon as he turns around at the top of the route, so the quarterback needs to anticipate the break. The receiver’s ability to sell a “go” route also helps — the receiver wants to make the cornerback think he has to cover deep before making his cut. That would make the defender off-balance and create natural separation as the defender tries to recover.

A well-run comeback route can help a team beat man coverage. Like the other outside-breaking routes, it’s good if a team needs to drive down the field in a two-minute drill since the receiver already is close to the sideline to stop the clock.

Best to run the route: Michael Irvin, Steve Largent, Terrell Owens, Jarvis Landry

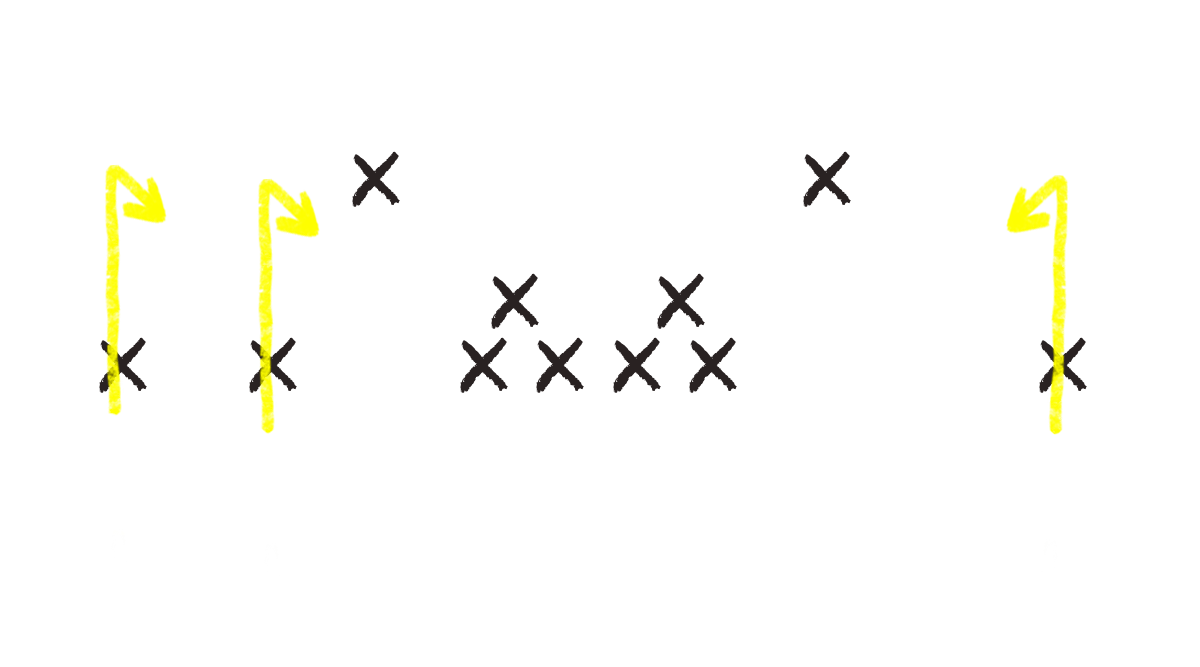

4 Curl

The curl — also called a “hook” or a “button hook” — is largely the same as the comeback route, with one key difference: When the receiver reaches the top of the route, he plants and turns back in toward the middle of the field. When run closer to the line of scrimmage (about five to eight yards downfield), a curl becomes a “hitch” route.

The curl relies heavily on timing and the ability to sell the go route. As soon as the receiver plants and turns, he should expect the ball to be there. At the same time, if he can convince the cornerback that he’s going deep, the inside break will be that much more effective as the defender has to react and make up ground.

The curl route is good against man coverage, for the above reason. It’s also part of several combo route concepts, including “curl-flat,” “smash,” “spacing” and “spot,” among many others.

Best to run the route: Michael Irvin, DeAndre Hopkins, Hines Ward

5 Out

The out can be run at pretty much any level of the field, though it’s usually run at about a 10-yard depth. The receiver runs straight ahead when the ball is snapped, then once he reaches the top of the route, he sharply cuts 90 degrees toward the sideline.

Here, the receiver needs to be aware of the distance between him and the sideline — and be prepared to toe-tap to stay inbounds if the pass is outside. The cut also is important — if it’s not crisp enough, the defensive back will know what’s coming and can jump the route.

Out routes are very common in two-minute drills and other time-saving situations since it’s a great way to get a decent amount of yards and stop the clock. They can beat both man and deep zone coverages — the outside break should fool the defender in man, while a shorter out route could allow an opportunity for some yards after the catch against a deep zone such as Cover 4.

Best to run the route: Larry Fitzgerald, Terrell Owens, Marvin Harrison, Cris Carter

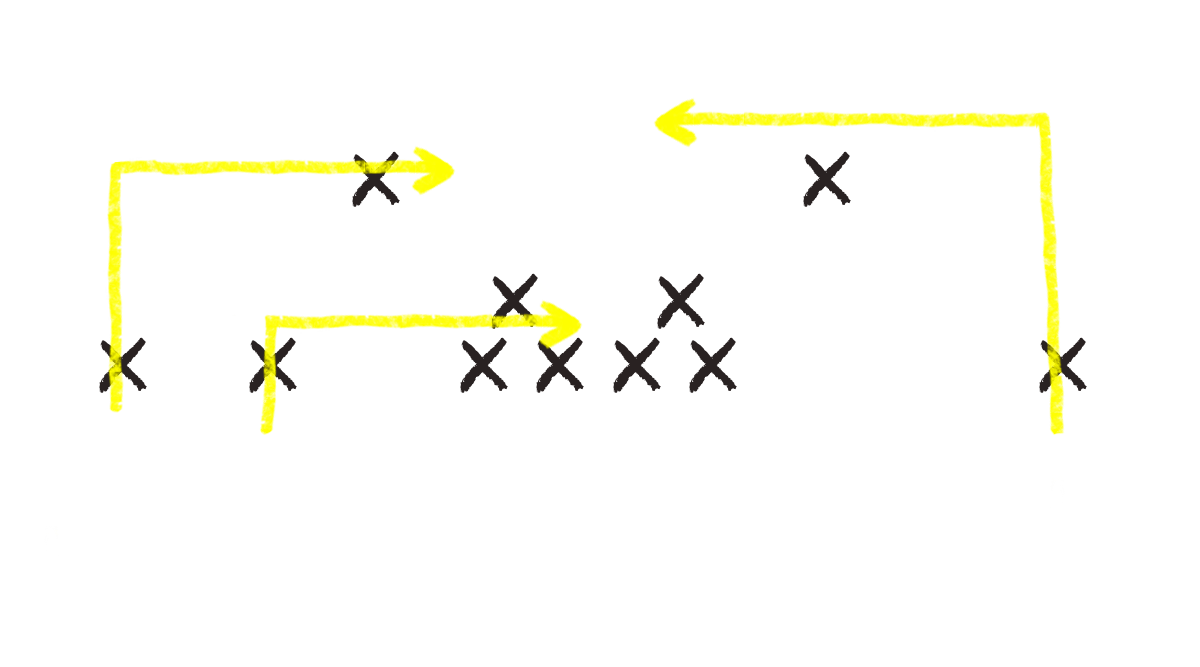

6 In

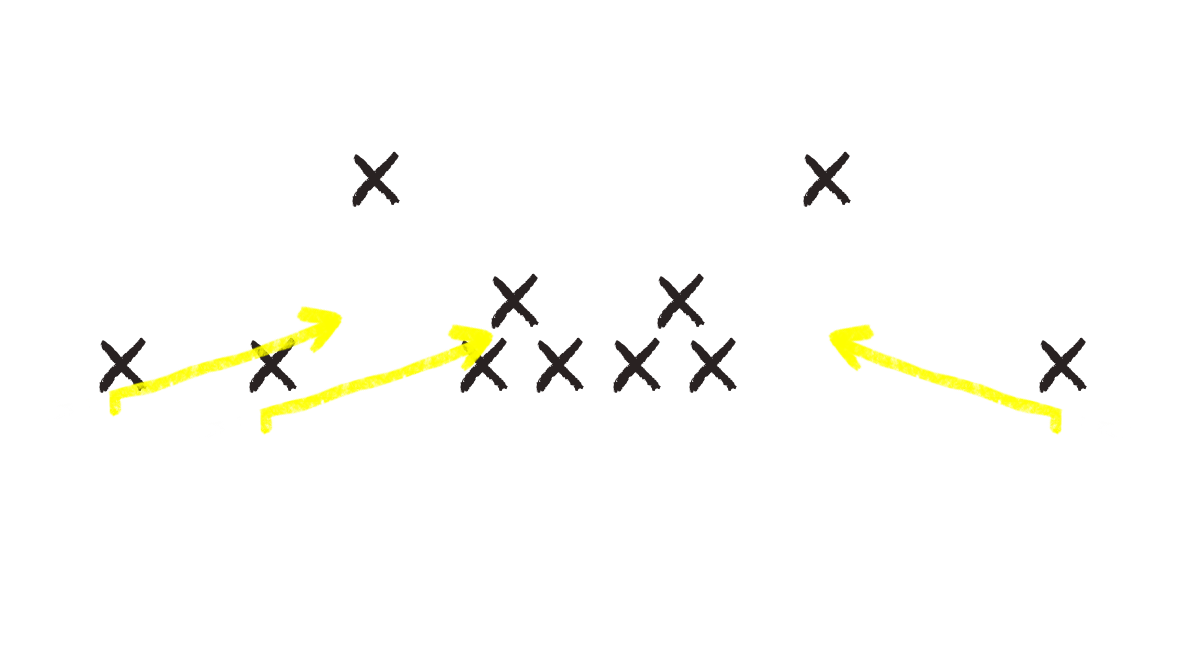

An in route (also called a “dig”) is the inside-breaking version of the out route.

An in route becomes a “drag” route when: (a) it’s run closer to the line of scrimmage with no stem, and (b) the receiver rounds off the route instead of sharply cutting inside.

The break on an in route needs to be crisp or else the receiver risks the defender diagnosing the play and putting himself in better position to jump the route. It also helps to have a receiver who can make catches in traffic since the middle of the field often is flooded with players.

Ins are very good against man coverage since the defender will have to recover against a strong-enough cut. Depending on the depth of the route, they can work against zone coverage — shorter routes can exploit deep coverage, while deeper ones can attack the area between the linebackers and the safeties. In routes also are used in several combo route concepts such as “levels” and “Mills”, while drag routes are popular in “mesh” combo routes or as checkdown options for a slot receiver or tight end.

Best to run the route: Larry Fitzgerald, Terrell Owens, Marvin Harrison, Cris Carter

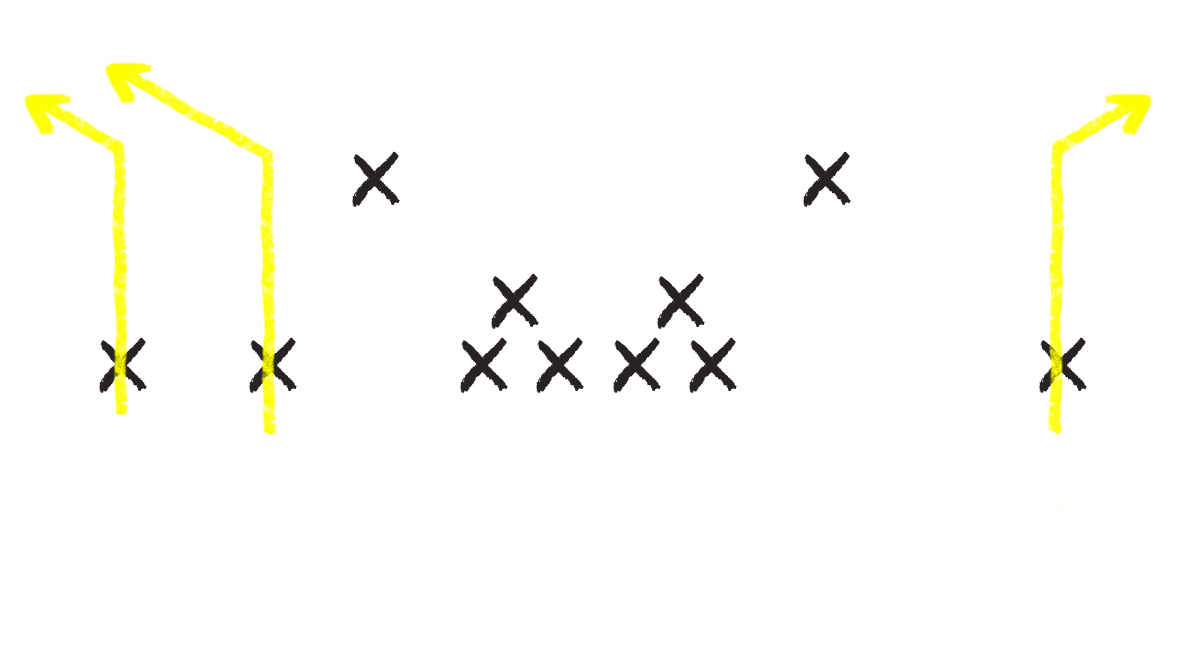

7 Corner

A corner route, also known as a flag route, attacks the deep portion of the field. The receiver runs straight ahead for 10-15 yards, then cuts 45 degrees and runs diagonally toward the sideline. It’s called a corner or a flag route because it often is run to the pylons (which were flags in the old days) in the corners of the end zone.

The receiver should be able to create separation with his cut. He can sell an inside-breaking route against the cornerback by turning his head inside toward the quarterback right before he plants his foot and cuts outside. The quarterback often will wait for the receiver to make the cut before throwing and should place the throw to the receiver’s outside shoulder to help avoid defenders.

Corner routes are great against Cover 2, since there are coverage holes along the sidelines between the corner (who is covering the flat) and the safety help over the top. They’re also useful whenever the offense needs to get out of bounds on a chunk play, and are common in the “smash” combo route — the inside receiver runs a corner route, while the outside receiver runs a hitch — and other concepts where the defender has to choose whether to cover deep or shallow.

Best to run the route: Cris Carter, Randy Moss, Jerry Rice, Odell Beckham Jr., Jordy Nelson, DeAndre Hopkins

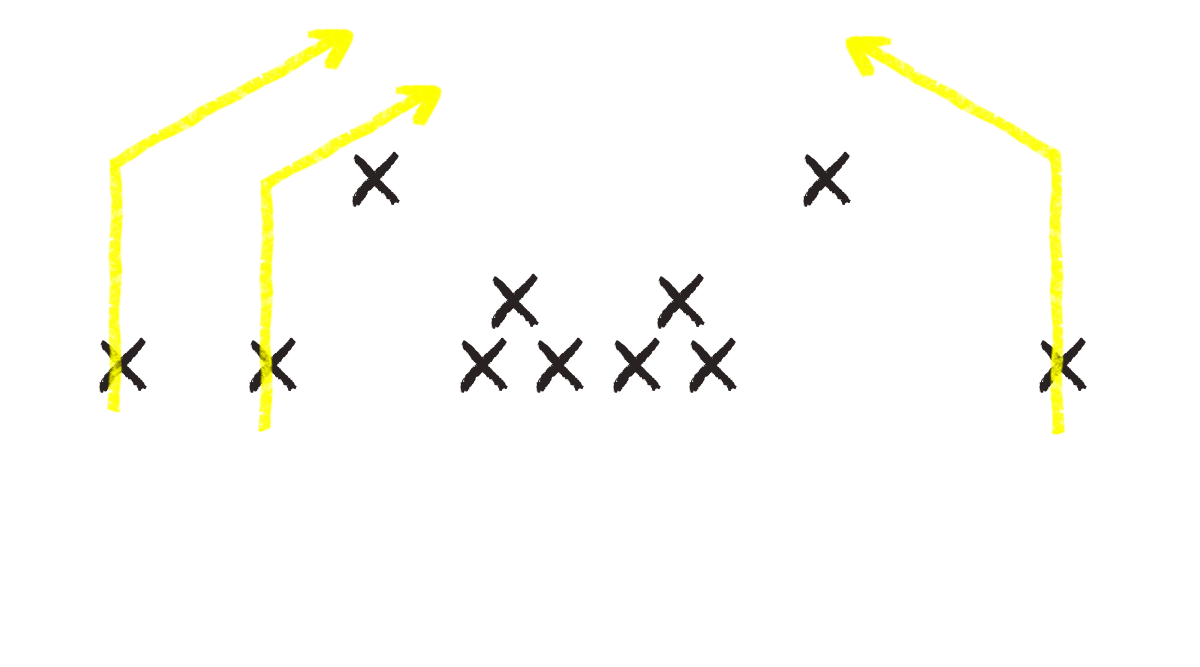

8 Post

The post is the inside-breaking variation of the corner route. The receiver runs 10-15 yards downfield, then cuts 45 degrees inside and runs across the middle of the field. It’s called a post route because the receiver is running toward the goalposts.

A common variation of the post route is the “skinny post” or “bang 8,” in which the receiver runs a less severe angle than usual — in essence, narrowing the route.

The receiver should be able to handle catches in traffic, since he’ll likely have a safety bearing down on him. And like the corner route, the receiver should be able to create separation from his initial defender on the cut.

Posts are good against defenses with a single-high safety, such as Cover 1 or Cover 3, since the inside break allows the offense to attack the defender over the top. They can work against man, but the receiver needs to get good inside positioning on the defender and the quarterback needs to loft the pass over any underneath defenders. Skinny posts are good against Cover 3, since the narrower route can attack the small seam between the outside cornerback and the safety responsible for the deep middle third of the field.

Best to run the route: Torry Holt, Terrell Owens, Jerry Rice, Al Toon

9 Go

This route has many names — you’ll also hear it go by “fly,” “streak” and “clearout” — but it’s the simplest of them all: a straight line downfield.

There are three ways a go route can play out: a pure over-the-shoulder throw-and-catch, a jump ball or a back-shoulder catch. The first is a result of pure speed — the receiver speeds by the defensive back, and the quarterback hits the receiver in stride. The second usually happens on underthrown passes, traditional over-the-top fades in the end zone, or instances where the receiver has a clear size advantage and can outmuscle his defender. The third is all about ball placement — the quarterback throws it behind the receiver, who adjusts based on where both he and the ball are in relation to the defender.

Of course, faster receivers such as DeSean Jackson are better at burning defensive backs, but bigger receivers also can have success on go routes. Jordy Nelson has mastered the back-shoulder fade concept with Aaron Rodgers, while Mike Evans uses his size and 37-inch vertical leap to make deep contested catches over defenders.

Go routes can beat both Cover 2 and 3, since the defense has only two (Cover 2) or three (Cover 3) defenders dropping back deep. So, if an offense sends enough players downfield, they should outnumber the defense. Go routes also can serve as decoys to take defensive backs out of the play and free up space for shorter underneath routes.

Best to run the route: Randy Moss, Tim Brown, Isaac Bruce, Tyreek Hill, Jackson, Evans, Nelson

Production: Nick Klopsis (with Bob Glauber) Design: James Stewart