It was a problem Jackie Robinson outlined in 1972, days before he died. As he looked out at the crowd attending the World Series between the A’s and the Reds, the same crowd that was currently honoring him, he wondered aloud: Where are the Black people in baseball?

At the time, the legendary Hall of Famer didn’t mean the guys on the field — Black players were becoming a strong, important presence in Major League Baseball — but the managers in the dugout.

If Robinson were around today, he likely would be pointing out the lack of Black men and women in baseball’s front offices. And he would have witnessed the consistent decline in the number of Black players through the decades — from 18.7% in 1981 to 6.7% in 2016, according to SABR, the Society for American Baseball Research.

It was a haunting irony: Robinson, the man who broke baseball’s color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers 74 years ago Thursday, was beginning to witness another color barrier. One that still exists.

“It all trickles down,” said baseball historian Rocco Constantino, author of “Beyond Baseball’s Color Barrier.”

“There’s the front office aspect of it, and the managerial aspect of it and that [comes from] the lack of Black players, and then you trace it back to the lack of African American participation at the youth level . . . and the rise of costs” to play baseball.

There are other repercussions, too.

“I can go to a baseball game and be the only African American in an entire section,” Hall of Fame reporter Claire Smith said. Smith is the first woman and fourth Black person to receive the J.G. Taylor Spink Award, given for “meritorious contributions to baseball writing.”

So why, as society generally begins to steer toward greater inclusion, is baseball lagging? And, more particularly, what steps can baseball take to change the course?

Half a dozen prominent men and women in baseball were asked that same question, and there was consensus — yes, it’s a problem and, yes, it’s solvable.

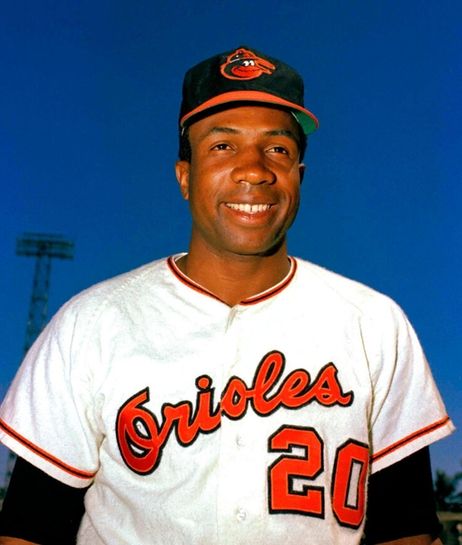

PHOTO CREDIT: AP

PHOTO CREDIT: AP

Frank Robinson

- Years as player: 1956-1976

- Years as manager: 1975*-1977; 1981-1984; 1988-1991; 2002-2006 *began as player-manager

- Teams managed: Cleveland, Giants, Orioles, Expos/Nationals

- Notable achievements: As a player, 14-time All Star and two-time World Series Champion. American and National League MVP. As a manager, the first Black man to hold the position. Named 1989 American League Manager of the Year

Since Frank Robinson became the first Black manager in 1975, while also playing for Cleveland, there have been 263 different men hired to manage baseball teams, according to Elias Sports Bureau. Sixteen of them have been Black. There are currently only two Black managers in baseball: Dusty Baker, with the Astros, and the Dodgers’ Dave Roberts. Since 2007, only two Black men have been hired as first-time managers.

As for Black heads of baseball operations — the people like general managers or presidents who hire managers, make trades and generally decide how baseball teams are run – there’s just one, according to MLB: White Sox executive vice president Kenny Williams, who earned that title in 2012 after also serving 12 years as general manager there.

There are only three other minority heads of baseball operations: The Marlins’ Kim Ng, who is Asian, and the first woman to ever be hired as a general manager; Tigers GM Al Avila, who is Cuban; and Giants president Farhan Zaidi, who has Pakistani ancestry.

THE PAST: Where have you gone, Frank Robinson?

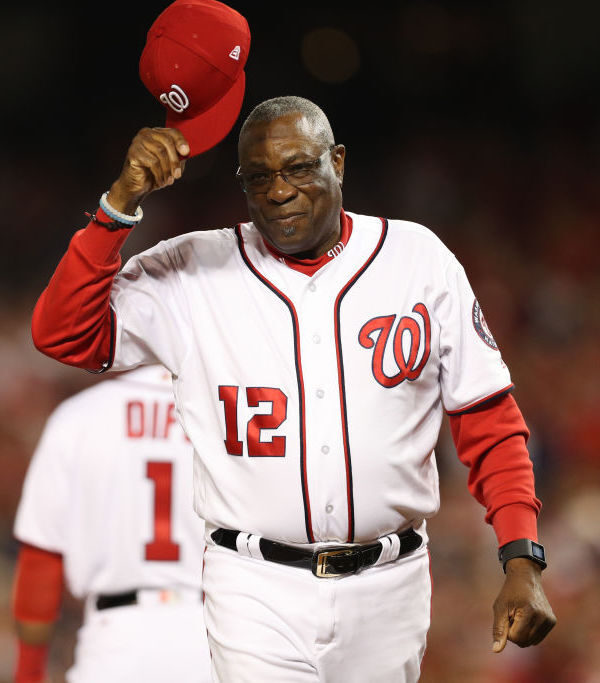

Dusty Baker, 71, is in his 24th season as a manager, and he knows baseball has a blind spot. It starts at the very top, he said, with the men in power suits networking and getting their mostly white friends big jobs.

“We don’t have any fraternity brothers or any friends, so to speak, upstairs that are doing the hiring,” of Black men as managers, said Baker, a three-time National League manager of the year. “How many probably qualified Black friends do most of the people upstairs have, period — in life or in the game? That’s where it starts. It also starts when baseball quit hiring former players for these positions and started hiring businessmen only.”

General managers used to come from a pool of ex-players, but that trend began to change in the 1980s, when it veered toward businessmen and lawyers. Baker didn’t have a GM that wasn’t a former player until 1985, two years after Sandy Alderson, formerly the A’s general counsel, ascended to the position.

PHOTO CREDIT: Getty Images

PHOTO CREDIT: Getty Images

Dusty Baker

- Team: Houston Astros, current manager

- Years as player: 1968-1986

- Years as manager: 1993-2006; 2008-2013; 2016-2017; 2020-present

- Teams managed: Giants, Cubs, Reds, Nationals, Astros

- Notable achievements: As a player, a two-time All Star and World Series Champion. As a manager, three-time National League Manager of the Year. Has led his team to the playoffs for six of the last seven seasons he’s managed.

As baseball steered toward the computational analysis of statistics in the late ’90s, the trend shifted again. Now, the preferred GM candidate for many is Ivy League educated, with a strong eye toward analytics, said Alderson, president of the Mets.

“Clubs are favoring that type of candidate over more traditional candidates. I think you have to look at, No. 1, whether that’s a good idea, and, No. 2, how to identify minority candidates with that background,” Alderson said.

He added: “The key is hiring at lower levels and bringing individuals in to create a pipeline. I think one of the problems, generally, that we have in the game is that the entry level, the internship level, there are some people who can afford to take on an internship and some people who can’t, and yeah, that has a big impact.”

Baseball internships pay less than first-year jobs at large tech companies or Wall Street firms, said Brian Cashman, general manager of the Yankees, who started his career with the organization as an intern. And since many of these analytic-minded candidates have degrees in business or statistics, the competition for them is fierce. A choice to start a career in baseball can sometimes fall to two factors: love for the game and the financial means to not take the highest-paying offer, Alderson said.

“It just comes down to how can we continue to find ways and initiatives to get an increase in the population within the Black community that will love the sport of baseball,” Cashman said. “There is a population. Is it represented enough as it should be in our industry? The answer is no.”

In 1999, then-commissioner Bud Selig sent out a memo requiring teams to interview minority candidates for five top-tier job positions, including general manager and manager, and though that mandate lives on today, it doesn’t always translate to minority hiring.

“There are people that are clearly qualified and clearly very respected in the game, [people] you never hear anything bad about [who don’t get jobs] and I just don’t know I can assume what’s not getting them their foot in the door,” Constantino said. “It’s mind blowing . . . A lot of places are filling the Bud Selig quota by interviewing Latin American candidates or women but not really hiring them, either.”

Michele Meyer-Shipp, a Black woman and MLB’s first chief people & culture officer, says she is glad the rule exists — but for it to work, there must be a deeper shift.

“The more I looked into this [rule], the more and more I realized that the rule is the rule and it’s words on paper,” she said. “We have to actually create an environment wherein we have the pipeline of talent to apply the rule to. It’s not good enough to find one person and put them through the process and check the box on the rule. We actually need to . . . get really intentional about looking across baseball and identifying the talent that we have in our pipeline right now.”

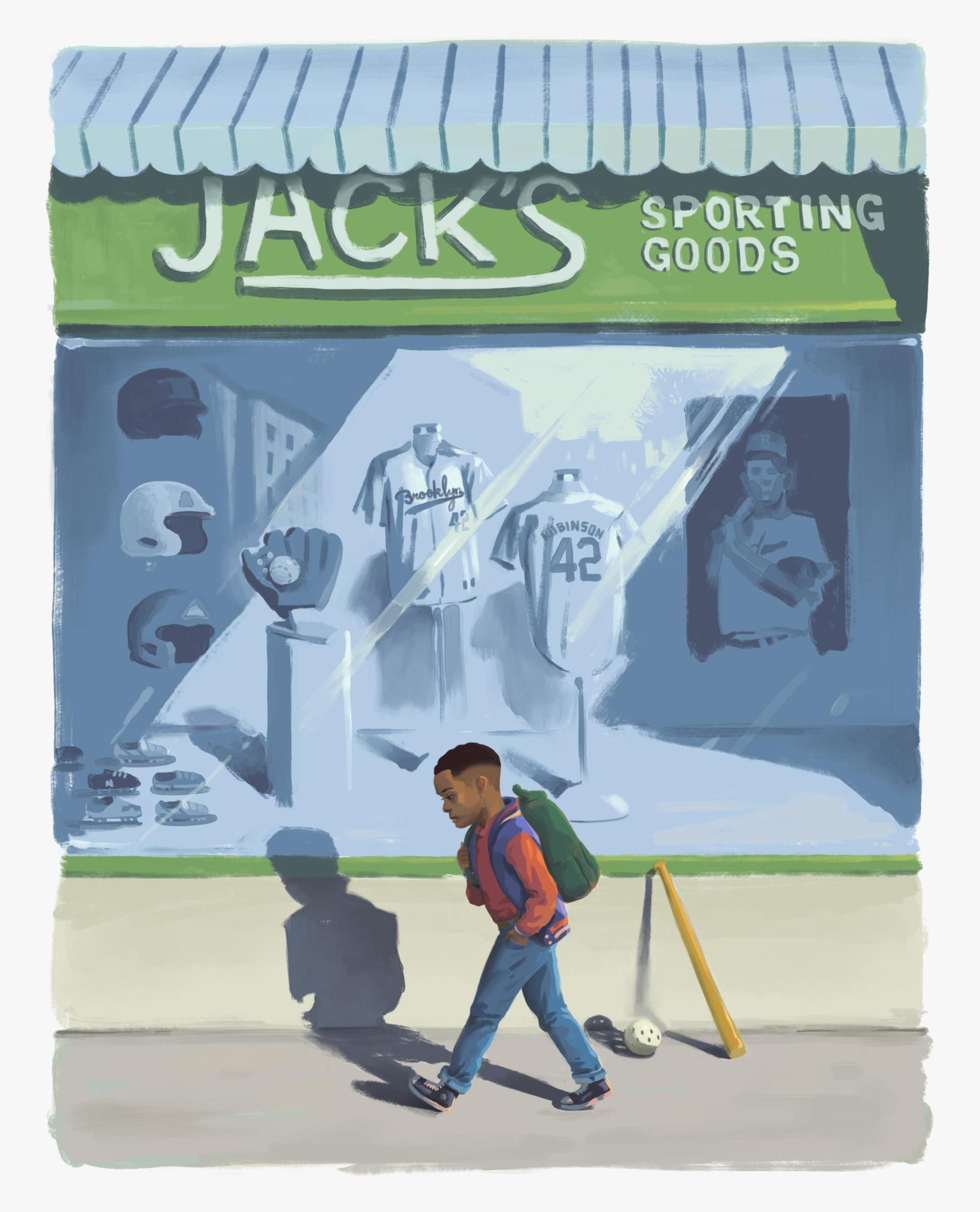

THE PRESENT: A Children’s Game?

Being good at baseball is an expensive endeavor.

According to a 2019 study by the Federal Reserve, the average white family in the United States has a net worth of $188,200, compared with $24,100 for Black families. It’s caused a schism between talented kids who can afford to pursue baseball and those who can’t, especially as children are being asked to specialize in a particular sport early on, Constantino said.

“The rise of the cost of youth level baseball over the past couple of decades” has been a big part of homogenizing the sport, he said. “It’s become a country club type sport, where it takes a lot of money and a lot of year-round training and a lot of elite club travel ball that inner city, underprivileged youth don’t have access to.”

To have a good shot at advancing though the ranks, youth players have to play travel ball. The average annual cost to play on a travel team is around $3,700, according to a study conducted by USA Today. That can balloon to around $8,000 for training and tournaments. Tack on hundreds of more dollars for equipment.

One impactful fix would be financing travel ball, Alderson said, which would allow kids to get into the sport when they’re still young and potentially capable of developing the skills they need to go pro.

“And I don’t mean holding showcases,” he said. “I mean subsidizing players that want to participate in travel ball but can’t for financial reasons.”

That’s not to say Black parents don’t spend money on sports, but specializing in one sport, while also taking costs into account, means making difficult decisions. Parents of Black children rated the possibility of earning a college scholarship as 23% more important than white parents, according to a 2020 survey by the Aspen Institute. Basketball and football scholarships are more accessible than baseball: There’s a greater number of them and they pay out more.

Smith said the issues Black children face are also different from the ones faced by Latin American players. Over 27% of MLB players are Latino, and there are four Latino managers. A lot of it has to do with the different rules that govern scouting and signing international talent.

“With Latin American players, you can spot a kid that’s 13, 14 years old, see the talent and you can sign that child,” she said. “You can tuck that child away in an academy because that child, unless he’s Puerto Rican, isn’t subject to the draft. There’s more certainty in pursuing the player in Latin America, and baseball is able to say, we’re more diverse than ever . . . but players of color and African Americans are not interchangeable.”

Compared to international players scouted at an early age, Black American children have to pay their own way, choose to specialize in a predominantly white sport, display their talents in expensive showcases and tournaments, and hope for the best.

“They can say, we’re more diverse than we’ve ever been, and yet, hidden in those numbers is the disappearing of the Jackie Robinson legacy.“

-Claire Smith, Hall of Fame reporter

THE FUTURE: Reaching out for more

But there are ways to remedy this, Meyer-Shipp said, adding that baseball is making strides in the right direction.

There are programs dedicated to youth outreach and bringing baseball to communities that may not have the ability to support the sport. And since 2012, nearly 20% of all first-round selections in the MLB Draft have been Black. Major League Baseball also has instituted a “Diversity Pipeline Program” meant to spot early on which minority candidates can begin to be groomed for either roles that are on-field or in baseball operations.

Baseball has worked to integrate Black men and women into league roles: Michael Hill, who interviewed for the Mets GM position but was passed over for Jared Porter (later fired for sending unsolicited sexually explicit texts to a female reporter), is now MLB’s vice president of on-field operations, a position that makes him the league’s top disciplinarian. Ken Griffey Jr. was named senior adviser to commissioner Rob Manfred. Tony Clark is the head of the players’ association, though that’s chosen by the players union.

MLB and the players association have also committed $10 million through 2024 to The Players Alliance, which helps fund programs set to improve representation of Black Americans in all levels of baseball.

“I think we all acknowledge that we have a lack of representation, and the good news is that there is a keen laser focus on doing all that we can to address that in some really proactive ways,” Meyer-Shipp said.

Not attracting Black players early on means missing out on some of the best talents of a generation, Smith said. Frank Robinson was a standout basketball player and could have gone that route. Jackie Robinson was a football and track star. When Black children feel alienated from the sport, either due to cost or lack of representation, they’re less likely to choose it as they get older.

THE EPILOGUE: What About Mookie?

If baseball wants to attract Black kids, Constantino said it could start by marketing Dodgers star Mookie Betts, arguably one of the top five players in the game. Betts is a former American League MVP and was the player who handed out food to the homeless before Game 2 of the 2018 World Series, and gave out masks, food and hand sanitizer during this pandemic.

Mookie Betts of the Los Angeles Dodgers catches a fly ball at the wall during Game 7

of the NLCS in October 2020. Credit: Ronald Martinez/Getty Images

Mookie Betts of the Los Angeles Dodgers catches a fly ball at the wall during Game 7

of the NLCS in October 2020. Credit: Ronald Martinez/Getty Images

“Players in the ’80s grew up watching Willie Mays and Hank Aaron, and Jackie Robinson was a mythical figure to them,” he said. “And right now, they [only have] Mookie . . . They need to do a better job of getting Mookie out there because how could you ask for a better role model?”

And until baseball tries to do that, there aren’t going to be kids who want to be like Betts. They’d rather be like LeBron James, the megastar of the NBA, or Patrick Mahomes, the extremely talented, extremely likeable Kansas City quarterback (his dad was Mets pitcher Pat Mahomes.)

“You’re not setting up role models for kids,” Smith said. “There’s no Michael Jordan. There’s no LeBron James. Baseball didn’t [initially] get involved in social justice issues [like Black Lives Matter] until the players did.”

All of which means that baseball needs to be more intentional if it wants to grow its Black fan base. And get its Black players back. And its Black managers. And its Black GMs.

“To me, it’s a menu of things that need to be done in order to rekindle that interest and ultimately end up with more minorities and women leading front offices,” Alderson said. “I think there are ways it can happen but I think it requires some attention.”

Illustrations by Neville Harvey/Newsday