Cassini the Saturn Spacecraft’s Fond Farewell

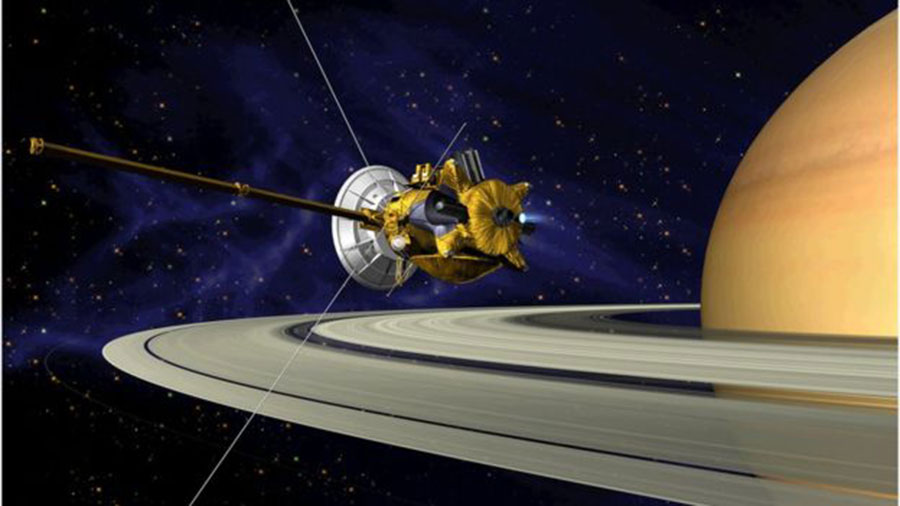

A billion-dollar spacecraft named Cassini burned up as it plunged into the atmosphere of Saturn today.

That’s the plan, exquisitely crafted. Cassini, the only spacecraft ever to orbit Saturn, spent the past five months exploring the uncharted territory between the gaseous planet and its dazzling rings. But now, it’s useful life is up.

Dreamed up when Ronald Reagan was president, and launched during the tenure of Bill Clinton, Cassini arrived at Saturn in the first term of George W. Bush. So it’s old, as space hardware goes.

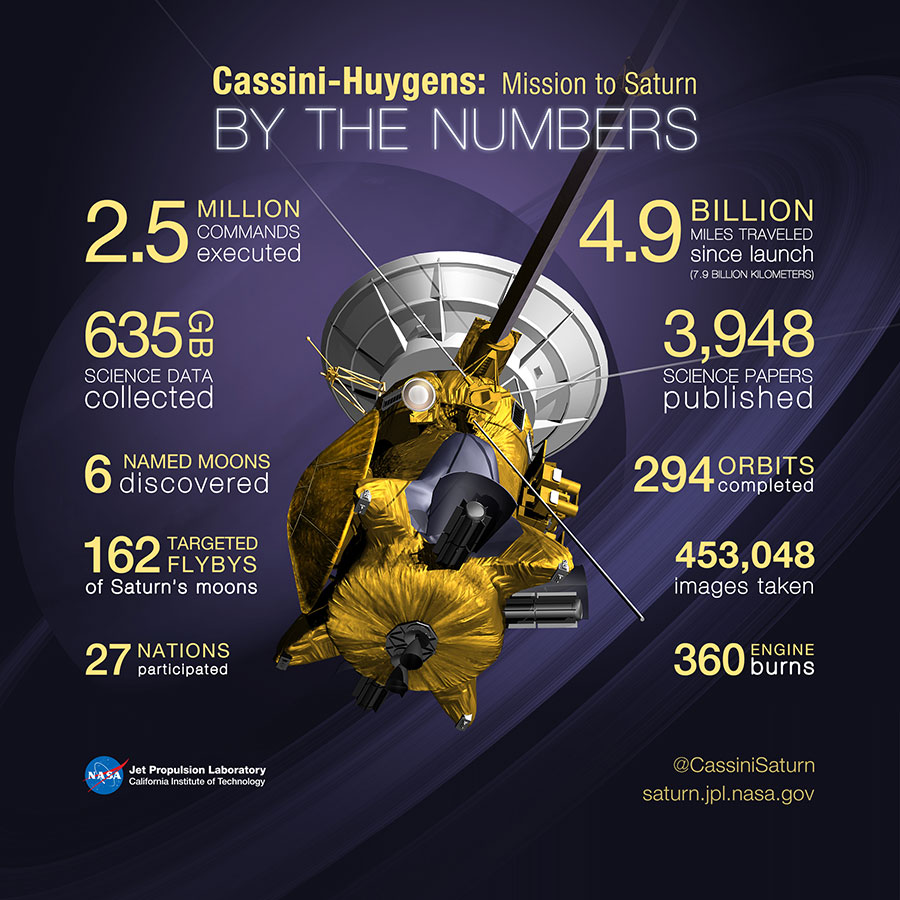

It has fulfilled its mission goals and then some. It has sent back stunning images and troves of scientific data. It has discovered moons, and geysers spewing from the weird Saturn satellite Enceladus. It landed a probe on the moon Titan. It would have kept transmitting data to Earth to the very end, squeezing out the last drips of science as a valediction for one of NASA’s greatest missions.

Earth received @CassiniSaturn’s final signal at 7:55am ET. Cassini is now part of the planet it studied. Thanks for the science #GrandFinale pic.twitter.com/YfSTeeqbz1

— NASA (@NASA) September 15, 2017

Images from @CassiniSaturn's #GrandFinale dive are being posted – https://t.co/yYbjbC4WLi #GoodByeCassini pic.twitter.com/bxIaQAxeFM

— NASA HQ PHOTO (@nasahqphoto) September 15, 2017

It was also running out of gas, basically, though precisely how much fuel was left is unknown. Program manager Earl Maize says, “One of our lessons learned, and it’s a lesson learned by many missions, is to attach a gas gauge.”

Cassini’s final orbits have taken it, amazingly, inside the rings of Saturn, where the spacecraft practically skims the tops of the planet’s clouds. These orbits can plausibly be compared to Luke Skywalker flying into that narrow trench on the Death Star.

“We’re kind of going through the mourning cycle,” said Julie Webster, head of spacecraft operations.

Here’s a look at Cassini — a NASA mainstay for two decades that’s about to meet its demise.

History

Cassini closes out an era in NASA space science. This is hardly the end of solar system exploration, but it’s essentially the end of the first, heroic phase – the initial reconnaissance of the planets.

The colossal scale of Cassini is a legacy of the go-big mentality of the early days of space exploration. The United States put men on the moon with a jumbo rocket, and NASA for a long time skewed toward muscle-bound spacecraft even when humans weren’t along for the ride.

No single event changed everything, but what happened to a spacecraft called Mars Observer in 1993 certainly had an impact. It was large and fully adorned with instruments. And then, one day shortly before it was to go into Mars orbit, it simply went silent and was never heard from again. It probably blew up, Webster said.

Space is hard. Space will break your heart. “It’s like a loss of a family member,” Webster said.

By that point, Cassini had already been conceived, the instruments already coming online, and so it was essentially grandfathered in to the old-fashioned go-big protocol. NASA Administrator Dan Goldin wasn’t a fan. He had a name for Cassini: “Battlestar Galactica.”

Actually, it wasn’t simply the “Cassini” mission. It was the “Cassini-Huygens” mission. The Europeans designed the Huygens probe, a separate vehicle that detached from Cassini when it passed close to Titan.

Arrival and discovery

After Cassini, launched in 1997, arrived at Saturn in 2004, Huygens disengaged from the main spacecraft and dropped through Titan’s thick clouds. It sent back details of an alien world that possesses a stew of complex organic molecules, including liquid methane. Hydrocarbons rain from the sky. There are lakes and rivers.

The highest-resolution color images ever of any part of Saturn’s rings. See more: https://t.co/Z0Knorle8a pic.twitter.com/zOasrb2sL1

— CassiniSaturn (@CassiniSaturn) September 7, 2017

It’s the only place in the solar system other than Earth known to have rain and open bodies of liquid on the surface.

Cassini also discovered something amazing about Saturn’s moon Enceladus: It has geysers spewing from its south pole. Almost certainly it has an interior ocean, sealed beneath ice, that contains great volumes of water and possibly hydrothermal vents.

14 hours watching the plume at Saturn’s moon Enceladus, our last dedicated observation of this singular scene https://t.co/EqLPb6MsbO pic.twitter.com/hW3BVUExcz

— CassiniSaturn (@CassiniSaturn) September 10, 2017

Someday NASA or some other space agency is likely to send a probe to Enceladus to sample those geysers and test them for indications of life.

“The legacy for which Cassini will be remembered will be Enceladus,” said project scientist Linda J. Spilker.

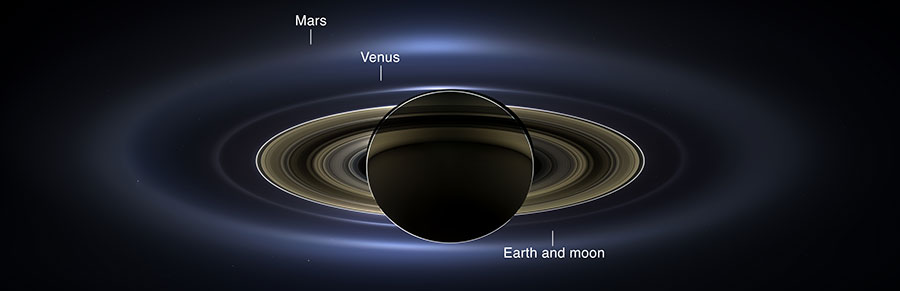

The day the Earth smiled

For a moment four years ago, the Cassini watched Earth from 900 million miles away. The probe had ducked behind Saturn. There, shielded from the sun’s rays, the robot turned its delicate lenses toward home. On July 19, 2013, Earthlings in the know waved and smiled for the paparazzo in the sky. Everyone else went about their day. Cassini, a gracious photographer, caught the entire Earth on camera anyway.

Perhaps no other Cassini photograph carries the emotional heft of “The Day the Earth Smiled.”

Astronomer Carolyn Porco, the leader of the Cassini imaging team, and her colleagues organized a campaign to smile into the void at 21:27 Coordinated Universal Time (accounting, of course, for light’s 15-minute dash from Earth to Saturn). It would be only the third time that Earth had been photographed from such a distance, after an earlier Cassini image and the Voyager portrait. It also marked the first time that Earth inhabitants knew they were being photographed from the outer solar system, beyond the asteroid belt.

“This could be a day, I thought, when all the inhabitants of Earth, in unison, could issue a full-throated, cosmic shout-out and smile a big one for the cameras from far, far away,” Porco wrote in June 2013.

The picture of Earth wasn’t the only image taken that day. The Cassini team ultimately stitched together 141 photos into a sweeping view of Saturn, a mosaic 404,880 miles across. Shot from the back, Saturn is a black ball suspended in ink, enclosed in the coffee-colored circles of its rings.

“On the one hand, it is a beautiful image that will serve as a reminder of all the great data Cassini obtained,” said Matthew Hedman, a physicist at the University of Idaho who was involved with the project. “And on the other, it contains a lot of information about the properties of the rings that we will be trying to understand for many years to come.”

Winding down

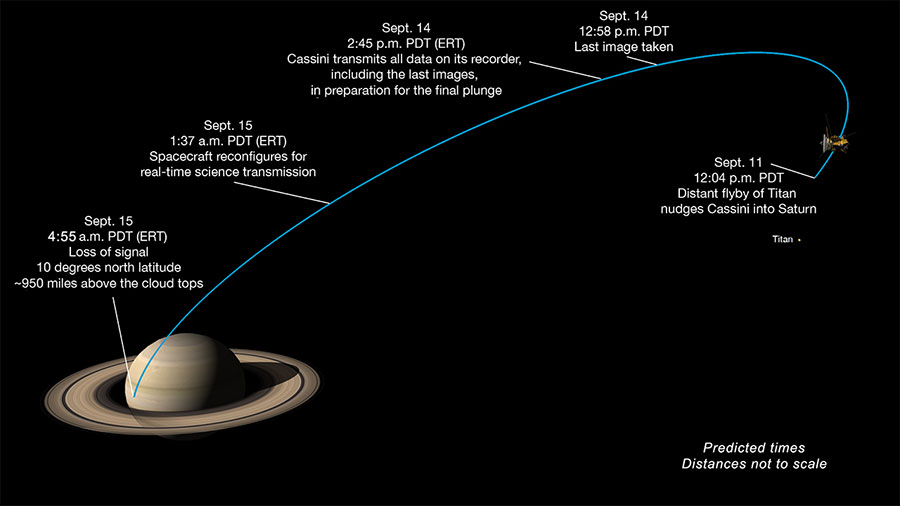

Cassini slowed down slightly in its final few orbits as it passed through the outermost layers of Saturn’s atmosphere. The drag on the spacecraft hastened the final plunge slightly.

At about 4:37 a.m. Eastern Standard Time today, the spacecraft was expected to roll into position to enable one of its instruments to sample Saturn’s atmosphere as it gets closer and closer to the planet. It would stream data back to the Deep Space Network.

In the final minute of its life, Cassini will have fired its thrusters in an attempt to keep its high-gain antenna pointing to Earth. But that is a battle Cassini was destined to lose.

Around 8 a.m. Friday, the final images taken by Cassini were streaming back to scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

But Cassini is already gone. It will have been destroyed 83 minutes earlier. That’s how long it takes at the speed of light for news to travel from Saturn to Pasadena.

Cassini did’t exactly “crash” into Saturn, because it’s a gaseous planet and there’s no surface to hit. In the last moments, the spacecraft will have gone into a tumble and lost contact with Earth. Then it burned up as it plunged through Saturn’s atmosphere and disintegrated.

And then nothing was left.