Inside Internal AffairsSuffolk police let Peter Fedden go after a drunken-driving crash. He got back behind the wheel and died.

Officer Michael Althouse drove the Commack deli owner home without a sobriety test. Minutes later, Fedden sped into a brick building and was killed. Althouse’s punishment? Counseling.

P

eter Fedden gave special treatment to the Suffolk County Police Department officers who bought meals, snacks and drinks at the deli he owned in Commack. They would slip him a $20 bill. He would give them $19 in change, whatever they bought.

Then, some officers gave Fedden a break that proved fatal.

Driving drunk, he lost control of his 1999 Chevrolet, careened more than 300 feet over front lawns, plowed through two chain-link fences and smashed into an unoccupied car parked in a driveway, according to police and court records and witnesses.

Five officers and a sergeant arrived at the scene.

No one subjected Fedden to field sobriety testing, as required by department regulations.

Instead, Officer Michael Althouse drove Fedden home without notifying dispatchers.

There, within minutes, Fedden, 29, got behind the wheel of his mother’s 2008 Honda and sped through an industrial park in Hauppauge. He lost control, this time at a speed estimated at more than 100 mph. The car went airborne, slammed through a brick wall and traveled more than 30 feet inside a building.

A helicopter airlifted Fedden to Stony Brook University Hospital, where he was pronounced dead. An autopsy showed he had a blood alcohol level of .15, nearly twice the legal level for driving while intoxicated, according to police records.

Behind the scenes of a Newsday investigation

After an internal affairs investigation, the Suffolk County Police Department moved to fire Althouse for failing to do his duty. County lawyers told an arbitrator that Fedden would still be alive if Althouse had performed a sobriety test and taken Fedden into custody, the arbitrator reported.

The arbitrator ruled against the county and authorized the department only to counsel Althouse that officers must notify a dispatcher when transporting a civilian.

Althouse, now 57, stayed on the job until he retired in 2019 with an annual pension of $136,131. He did not respond to requests for comment.

Newsday’s Inside Internal Affairs investigation has revealed through case histories that the internal affairs systems of the Nassau and Suffolk police departments have allowed officers to escape most or all discipline even in cases involving serious injuries or deaths.

Newsday reconstructed the events that led up to Fedden’s death through police and court records. After reviewing Newsday’s findings, six experts in drunken driving and the law concluded that police failed to conduct a basic investigation at Fedden’s first crash, covered up evidence that he was intoxicated and avoided subjecting him to standard field sobriety testing.

“This shocks the conscience, it really does,” said Karl Seman, a Garden City-based criminal defense attorney who has taught classes on defending alleged drunken drivers.

From the editors

Long Island’s two major police departments are among the largest local law enforcement agencies in the United States. Protecting and serving, the Nassau and Suffolk county police departments are key to the quality of life on the Island — as well as the quality of justice. They have the dual missions of enforcing the law and of holding accountable those officers who engage in misconduct.

Each mission is essential.

Newsday today publishes the fifth in our series of case histories under the heading of Inside Internal Affairs. The stories are tied by a common thread: Cloaked in secrecy by law, the systems for policing the police in both counties imposed little or no penalties on officers in cases involving serious injuries or deaths.

This case documents how a provision in the Suffolk police contract worked to stop that department from firing an officer despite finding that he had failed to perform his duty at the scene of a drunken-driving crash, with a fatal consequence. The county concluded that Officer Michael Althouse’s actions cost the life of 29-year-old deli owner Peter Fedden — yet was limited to subjecting Althouse to counseling for a comparatively minor rule violation.

Newsday has long been committed to covering the Island’s police departments, from valor that is often taken for granted to faults that have been kept from view under a law that barred release of police disciplinary records.

In 2020, propelled by the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the New York legislature and former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo repealed the secrecy law, known as 50-a, and enacted provisions aimed at opening disciplinary files to public scrutiny.

Newsday then asked the Nassau and Suffolk departments to provide records ranging from information contained in databases that track citizen complaints to documents generated during internal investigations of selected high-profile cases. Newsday invoked the state’s Freedom of Information law as mandating release of the records.

The Nassau police department responded that the same statute still barred release of virtually all information. Suffolk’s department delayed responding to Newsday requests for documents and then asserted that the law required it to produce records only in cases where charges were substantiated against officers.

Hoping to establish that the new statute did, in fact, make police disciplinary records broadly available to the public, Newsday filed court actions against both departments. A Nassau state Supreme Court justice last year upheld continued secrecy, as urged by Nassau’s department. Newsday is appealing. Its Suffolk lawsuit is pending.

Under the continuing confidentiality, reporters Paul LaRocco, Sandra Peddie and David M. Schwartz devoted 18 months to investigating the inner workings of the Nassau and Suffolk police department internal affairs bureaus.

Federal lawsuits waged by people who alleged police abuses proved to be a valuable starting point. These court actions required Nassau and Suffolk to produce documents rarely seen outside the two departments. In some of the suits, judges sealed the records; in others, the standard transparency of the courts made public thousands of pages drawn from the departments’ internal files.

The papers provided a guide toward confirming events and understanding why the counties had settled claims, sometimes for millions of dollars. Interviews with those who had been injured and loved ones of those who had been killed helped complete the forthcoming case histories and provided an unprecedented look Inside Internal Affairs.

He called the police response a “tragedy, in that the cops, thinking that they were doing a solid for one of their own, ended up killing him. Because, but for their — I’ll use the word — unfettered, improper discretion, this guy would be alive.”

Harry Thomasson, a lawyer who represented Fedden’s mother, Kathi Fedden, in lawsuits against Ruby Tuesday and Suffolk County, said Fedden was “a marvelously talented, gentle, kind artist, and had too much to drink, had too much marijuana one night, had some very poor judgment.

“And no one protected him from himself.”

The night no one saved Peter Fedden

Fedden bought Commack Breakfast in 2005 after working there part time while majoring in political science at C.W. Post College, now known as LIU Post. He finished his degree by taking night classes, often working seven days a week behind the counter.

“Someone he knew would come in and he’d say, ‘Are you hungry today? I’m going to make you something special. You don’t even know what I’m going to make you,'” Kathi Fedden, a court stenographer, recalled in an interview after her son’s death.

On the night of July 30, 2013, Fedden worked at a friend’s restaurant because the chef had called in sick. After finishing up, he drove to a since-closed Ruby Tuesday restaurant on Jericho Turnpike in Commack. He had two drinks at the bar, each 10 ounces of Jack Daniel’s whiskey with ice and a splash of soda in a 16-ounce glass, according to his mother’s lawsuit.

Bartender Joelle Dimonte was friendly with Fedden. She said in a Newsday interview that Fedden “would go above and beyond for his friends” and that he often gave free meals to police at Commack Breakfast.

“They would go there for big breakfasts,” Dimonte recalled.

Fedden left Ruby Tuesday after less than 90 minutes around 11 p.m., drove to the deli and smoked marijuana, the lawsuit states. Then he took off in his car, accompanied by Dimonte and Douglas Nigro, a man he had met that night.

Fedden picked up speed. He lost control on New Highway near the intersection of Mohegan Lane. After crossing the lawns and plowing through the two fences, he smashed into the parked car with a force that pushed it 20 feet up the driveway into a garage door.

The impact shook the house, according to the internal affairs file.

Off the road at high speed

Fedden lost control on New Highway near Mohegan Lane in Commack. Credit: Chris Ware, Jeffrey Basinger

Robert Rupnick rushed from his home across the street.

“We didn’t hear any braking sound, just a loud bang,” Rupnick, a chiropractor, said in a Newsday interview.

A woman who lived nearby told investigators she heard the crash from inside her basement, went to the street, saw Fedden get out of his car, and heard him yell, “I’m drunk. I’m drunk,” followed by three obscenities. She called 911 and reported what the driver had said, according to the file. The dispatcher radioed that the crash involved a “possible intoxicated driver.”

Rupnick said he spoke to Fedden and found him to be lucid.

“There wasn’t, to my interpretation, anything that seemed like he had been under any influence of drugs or alcohol,” Rupnick said, adding, “I asked him what happened, and he says, ‘I swerved to avoid a raccoon or a cat on the road.’”

Drivers often offer similar explanations for crashing, said Robert E. Brown, a former NYPD captain who now is a defense attorney.

‘Swerving to avoid an animal is a standard story.’

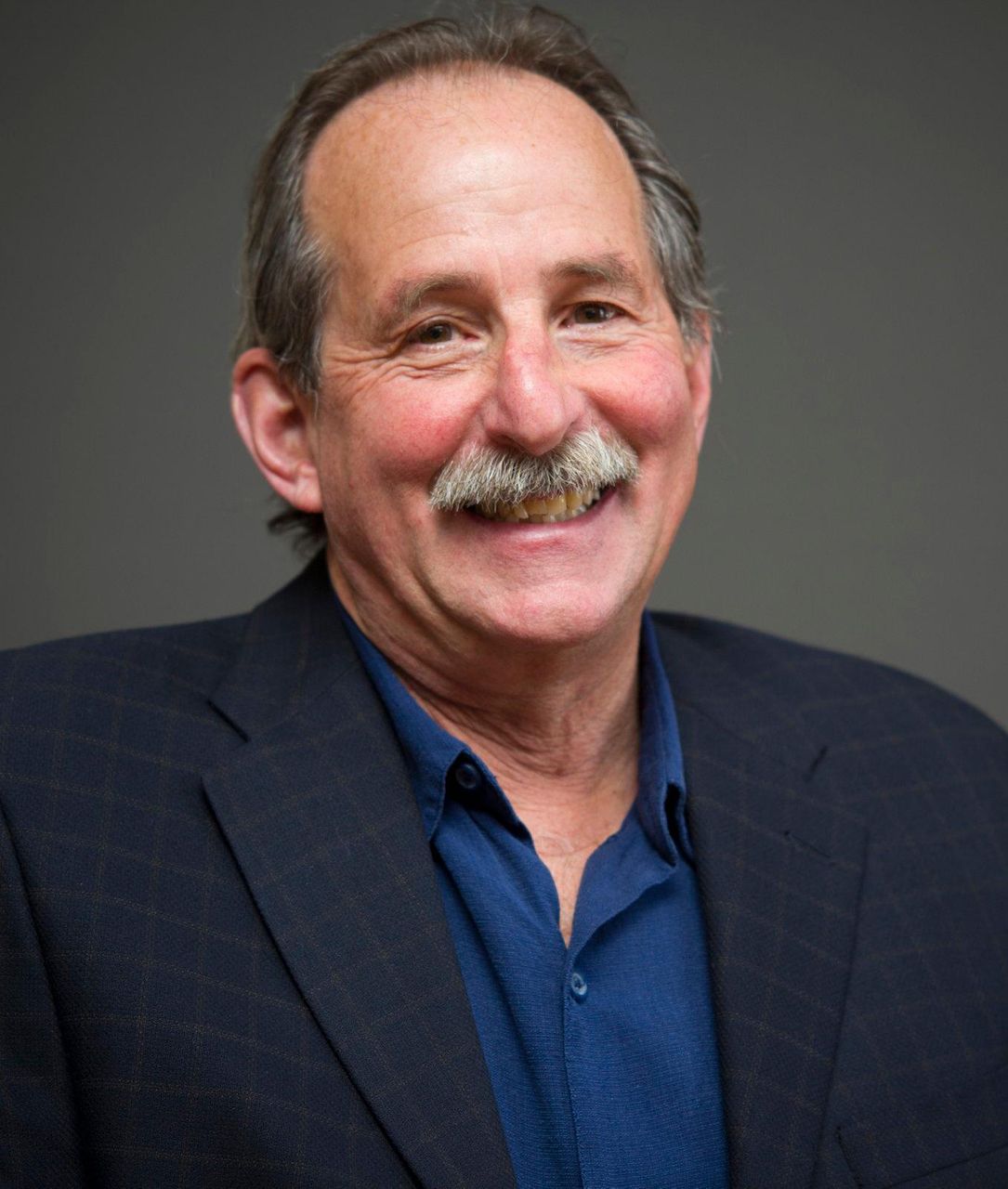

DWI defense attorney and former NYPD captain Robert E. BrownPhoto credit: Amessé Photography/Vinnie Amessé

“Swerving to avoid an animal is a standard story,” he said.

Fedden’s passengers emerged from the disabled car. Althouse reached the scene five minutes after the crash, according to police records. He was followed by four officers and a sergeant. The four officers who responded were not named in the file.

Althouse completed a police report about the crash. He cited “unsafe speed” and “animal action” as contributing factors to the crash. He did not note that there had been passengers in the car.

Speaking with Newsday, Dimonte said that police told Nigro and her to leave the scene. She also recalled that Fedden was placed in the back seat of a police car and smiled at her through a rear window as the car drove away. It was the last time she saw him.

Nigro did not respond to interview requests.

The owners of the car that Fedden hit were in Florida. Their son, Jody Calabrese, arrived. Police assured him that the driver was fine and told him, unprompted, that the driver was not drunk, Calabrese said in an interview with Newsday.

He recalled surveying the damage and being stunned that a police officer had taken Fedden away without calling an ambulance. He also remembered telling Rupnick, “It was a serious accident. How do they know he didn’t bump his head?”

Fedden’s home was a four-minute drive away. Althouse brought Fedden there — never notifying a dispatcher that he was transporting a civilian, as required by department rules.

Minutes later, Rupnick and Calabrese heard a police radio call: A car had gone off a roadway and crashed into a building in Hauppauge.

“Another one?” Rupnick recalled hearing an officer say.

Dropped off by Althouse, Fedden had taken the keys to his mother’s Honda and gone out again. He drove east on Commerce Drive at a speed estimated by police to be 100 mph, barreled into a parking lot, went airborne and crashed into a brick building.

Penetrating the wall, the car destroyed a conference room and test kitchen of Advantage Marketing, a food service brokerage, the company’s owner, Mitch Levine, said in an interview.

An officer, whose name was blacked out, reported finding an unidentified driver “unresponsive with shallow breathing.” His legs were pinned under the dashboard.

Althouse also responded to the 911 call, joined efforts to extricate the driver from the wreckage, and flew with him in a helicopter to Stony Brook University Hospital.

There, medical staff gave Althouse a folded piece of paper they found in the driver’s pocket. It was then that Althouse learned who the crash victim was. The paper was a copy of the report Althouse had written about Fedden’s first crash, according to a report he filed with the department.

Sequence of events

- 1 11:23 p.m. Fedden drives across yards, crashes into parked car.

- 2 11:55 p.m. Officer drives Fedden to his mother’s home.

- 3 12:07 a.m. Now driving his mother’s Honda, Fedden crashes into a building and dies.

Fedden was pronounced dead at 1:05 a.m., July 31.

The level of alcohol in his blood was still almost twice the legal limit for driving when an autopsy was done several hours later.

“Thank God Peter didn’t kill somebody” else, said Levine, who, too, had known Fedden as a friendly deli owner.

How police failed Fedden

Police are trained under National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration guidelines to conduct investigations of drunken driving in three phases, said Steven Epstein, a Garden City attorney who specializes in drunken-driving cases and teaches DWI defense to attorneys.

The first phase entails studying how the driver operated the vehicle — whether, for example, the driver had been speeding or had lost control.

Then an officer looks for signs of intoxication. This entails observing drivers for unsteadiness, slurred speech, the odor of alcohol, bloodshot eyes and difficulty producing a driver’s license.

An officer typically questions witnesses, including passengers and other drivers, with a goal of understanding what happened before the crash.

An officer typically asks, ‘How much have you had to drink today?’

Eric Sills, attorney-author specializing in drunken driving and the lawPhoto credit: Akullian Creative

“An officer arriving at a scene of an accident typically asks the person where they’re coming from and where they’re going to,” said Eric Sills, an Albany attorney who has co-authored a book about representing clients charged with driving while intoxicated.

“And if there’s any reason to believe that the person has been drinking or using drugs, there typically would be questions regarding that, such as, have you been drinking? Or how much have you had to drink today?”

If the officer spots physical signs of intoxication, a witness reports evidence that a driver was intoxicated or a driver came from a place such as a bar or party where alcohol is typically consumed, the officer moves to the third phase: field sobriety tests.

This can include a gaze exam, in which an officer observes how eyes follow an object moving across a person’s horizontal field of vision; the walk and turn test, which involves taking nine heel-to-toe steps in one direction and back; and the one-leg stand.

Failure to successfully complete those tests gives police grounds to ask a driver to take a preliminary breath test, known as a PBT.

A driver who refuses to take a PBT, or whose breath shows traces of alcohol on a PBT, is typically taken into custody for more sophisticated testing at a police precinct. There, police will most commonly ask the driver to submit to a chemical breath test, such as a Breathalyzer or an Intoxilyzer, whose results are accepted as evidence in court.

Refusal to take such a test typically results in an automatic one-year driver’s license suspension.

Drunken-driving experts who reviewed Newsday’s findings pointed to five departures from police protocol:

The car’s trail of damage should have prompted an investigation.

“A quick look around the accident scene will give a trained officer an indication that there was high speed,” said John Powers, a West Islip-based attorney who specializes in DWI cases.

Seman said that the Chevrolet’s path from the roadway to smashing into a car parked up a driveway could itself offer “proof of intoxication or impairment.”

“This is not somebody that hits the curb or somebody that falls asleep at the traffic light. This is a huge crash. Look at the property damage involved,” he said. “You would expect someone who was not intoxicated or not impaired to have better control of their vehicle.”

Fedden very likely smelled of alcohol.

A standard drink contains 1.25 ounces of alcohol. Consuming 10 ounces would be the equivalent of eight drinks. Someone who consumed that much whiskey in just one drink would give off a strong odor of alcohol, Seman said.

Pointing out that the autopsy took place hours after Fedden died, he also estimated that Fedden’s blood alcohol level would have been close to double .15 at the time of the first collision in Commack.

A witness reported that Fedden had yelled, “I’m drunk. I’m drunk.”

Suffolk police protocols require that dispatchers relay reports of intoxication to responding officers. IA investigators confirmed from 911 recordings that the witness reported that she heard Fedden say he was drunk and that the police dispatcher relayed the call as a “possible intoxicated driver.”

The protocols direct officers to perform sobriety testing if a dispatcher reports possible drunkenness. None of the officers tested Fedden.

“His statement to civilians who have no reason to lie, ‘I’m drunk. I’m drunk,’” followed by obscenities, “is enough to arrest him” if the officer is aware of it, Seman said. He added that standard procedure called for detaining Fedden and, “at a minimum,” subjecting him to sobriety tests.

Police told the witnesses to leave the scene without questioning them.

Suffolk police regulations direct officers to “interview the parties involved” in a collision, along with witnesses.

Althouse’s crash report did not reflect the presence of passengers in Fedden’s car, as required. It also showed no indication that any of the officers interviewed Fedden, Dimonte or Nigro, who knew both that he had been drinking and that he had driven recklessly. Instead, Dimonte’s account that police told her and Nigro to leave the area suggests an attempted cover-up, the experts in the law of drunken driving said.

“You have witnesses to a potential criminal offense at your fingertips. You’re allowing very important investigative information to walk away from you, of what clearly could be a criminal offense,” Powers said.

‘…potentially, you have witnesses who were there and can tell you things.’

Drunken-driving defense attorney Steven EpsteinPhoto credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

Epstein said: “You have witnesses at the scene who can probably give you information about how the accident took place because if you’re doing an investigation into an alcohol-related accident, potentially, you have witnesses who were there and can tell you things.”

He continued: “It’s not very consistent with proper procedures to tell people involved in a car accident to leave the area unless they’re trying to have them not interviewed.”

Additionally, Althouse’s crash report shows no indication that officers located and interviewed the woman who reported hearing Fedden say, “I’m drunk. I’m drunk.”

Violating regulations, Althouse drove Fedden home without notifying a dispatcher.

“If you get arrested for drunk driving or driving while impaired, you don’t get to go home, just for that very reason,” said Brown, the former NYPD captain. “You need to go through the system because they want to make sure you’re not intoxicated when you get out.”

“Why do you think the cop did that?” Seman said. “’Cause he doesn’t want anybody to know that he’s giving his buddy a break and taking him home. ’Cause he doesn’t want anybody to know that this guy was at the scene. ’Cause he doesn’t want anybody to know that there was police involvement.”

Powers said Althouse put himself in jeopardy by driving Fedden home.

“It could be perceived that he’s giving aid to someone who had committed a crime,” he said. “You’re tampering with the witness of a crime.”

John Bandler, a former state trooper who teaches at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said he was always concerned about releasing a driver who may have been drinking.

‘You made a judgment call and let them drive and they killed someone, you are on the hook as a cop…’

Former state trooper John BandlerPhoto credit: Gail Bandler

“You made a judgment call and let them drive and they killed someone, you are on the hook as a cop, your discretion was wrong,” he said.

Letting Fedden go “emboldened” Fedden, Powers said.

“When you’re 29 years old, and you’re high and you’re intoxicated and you just got a pass, you’re invincible,” he said, adding:

“My gut reaction to hearing all the facts of the case is that here police officers are showing discretion to help this individual, and unfortunately, it cost him his life.”

How police escaped discipline

The crash happened in Althouse’s Fourth Precinct patrol sector. That gave him the primary responsibility for determining what had happened. At the same time, regulations required all the responding officers to request sobriety testing if they detected evidence that Fedden was intoxicated, Powers said.

The file shows no evidence that internal affairs interviewed any of the officers who responded to the scene. Instead, internal affairs permitted Sgt. Matthew Scaduto and the four additional officers to submit written statements. All wrote that they declined to waive the constitutional right against self-incrimination and that their accounts could not be used against them in criminal proceedings.

Their statements were each less than a page long.

The four officers who joined Althouse at the scene wrote that they had no contact with Fedden, did not know who he was until after the second crash and had no knowledge of whether he was subjected to sobriety testing. None of the officers mentioned witnesses.

One wrote that he helped guide traffic around the crash.

“I never saw or knew driver of vehicle involved,” this officer wrote. “I also had no interaction with driver.”

A second wrote that he saw Althouse in the driver’s seat of his patrol car and Fedden in the rear seat.

“Althouse advised that he did not need an assist with traffic control, and we left the scene,” this officer stated.

A third wrote that he saw that no one was inside the crashed car and saw that officers were “speaking to civilians.”

“Due to their distance and it being dark out, I was unable to see who they were speaking to,” this officer wrote. “I waited near the vehicle for a few minutes, and upon realizing my assistance wasn’t needed, I left the scene.”

A fourth officer recalled that Fedden’s car was towed.

Although he was the supervising sergeant at the crash site, Scaduto reported that he did not know who the driver was and had no contact with him. He wrote:

“I did not know the identity of the driver involved in the [crash] and had never met him before. I did not have any interaction with the driver and did not observe any signs of intoxication. I did not observe field sobriety tests being administered.”

The assertions by the four officers and Scaduto that they had no interaction with Fedden strained credulity, said Lee Adler, who teaches at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations and has studied police discipline.

“When you have an accident like that and it’s late at night, it’s very hard for a civilian to imagine that everybody let this go on without any inquiry,” he said, adding, “The statements made by the police officers about what occurred at the scene closed down the possibility for more careful examination.”

‘The statements made by the police officers…closed down the possibility for more careful examination.’

Lee Adler, Cornell University lecturer who has studied police disciplinePhoto credit: Cornell ILR School

Only Althouse acknowledged having contact with Fedden. Internal affairs summarized an incident report he filed as saying that Fedden showed “no signs of any physical or emotional impairment” and was “polite and cordial and in good spirits” when Althouse drove him home. There, Althouse wrote, Fedden thanked him and walked to his front door.

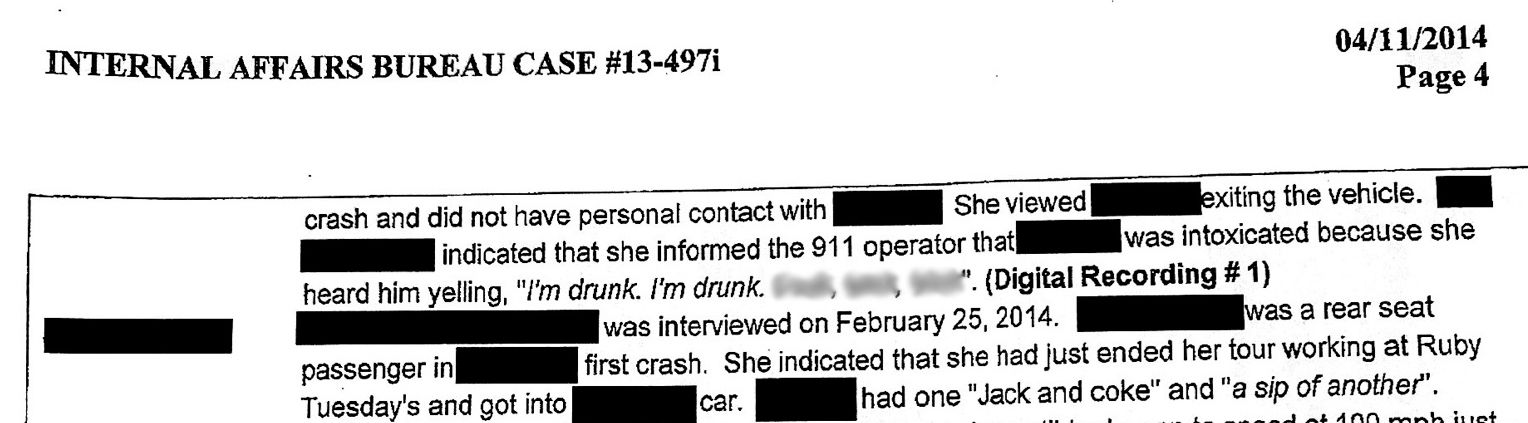

The internal affairs file includes one-paragraph summaries of interviews with Fedden’s passengers.

According to the summary of Dimonte’s interview, she reported that Fedden had consumed one “Jack and coke,” a reference to Jack Daniel’s whiskey, and “a sip of another.” She also said that Fedden “appeared normal” until “he began to speed at 100 mph” and that she wouldn’t have gotten into the car if she thought he was drunk.

A witness reported that Fedden “had ‘one Jack and coke’ and ‘a sip of another.’” Internal affairs report as redacted. Expletives blurred by Newsday.

Nigro said he saw Fedden have one drink, according to the summary of his interview.

The investigation substantiated three charges against Althouse.

- First, internal affairs found that Althouse “should have recognized Fedden’s intoxication and arrested him at the scene of the first motor vehicle crash.”

Investigators based the finding on statements by Dimonte and Nigro that they had witnessed Fedden drinking at Ruby Tuesday, as well as on a statement by the neighborhood resident that she heard Fedden yell that he was drunk. Internal affairs also noted that police received the 911 call about Fedden’s fatal crash 12 minutes after Althouse dropped him off.

- Second, internal affairs found that Althouse had failed to properly document the first crash because his report did not reflect that Fedden had two passengers.

- Third, internal affairs concluded that Althouse had violated Suffolk Police Department regulations by failing to notify a dispatcher that he was transporting a civilian member of the public.

Internal affairs substantiated a single charge of improper supervision against Scaduto, finding that he “knew or should have been aware of the vehicle operator’s intoxication” because of the 911 call and the suspicious circumstances of the first crash, the file says.

The department moved to terminate Althouse. He fought to keep his job.

Under New York state civil service law, an officer charged with misconduct can request a hearing before an examiner appointed by the police commissioner. The examiner issues a ruling, but the ruling is not binding. The commissioner retains the final authority to decide whether an officer will be disciplined and how tough the punishment will be.

At the same time, the law enables police unions to negotiate contracts that establish different disciplinary procedures.

In Nassau County, the commissioner has held power over discipline for the last decade.

In 2012, then-Commissioner Thomas Dale persuaded the county Legislature to repeal a law that allowed officers to seek binding arbitration if they faced the loss of 10 or more days of pay. After the Nassau Police Benevolent Association sued, the state’s highest court upheld the commissioner’s power.

In Suffolk, the PBA negotiated a contract that stripped the police commissioner of sole authority over discipline in the early 1980s.

Suffolk officers facing punishments more severe than the loss of five days of pay have two choices: They can opt for an internal police department hearing whose conclusions are presented to the commissioner for endorsement, modification or rejection, or they can choose a hearing conducted by an arbitrator selected jointly by the department and the PBA. The arbitrator’s ruling is binding.

Top police officials have insisted that commissioners should have the power to make the final decisions over discipline.

“It’s inconceivable to hold a commissioner of police responsible for organizational discipline when he has no control over the punitive discipline in the department because the arbitrator ultimately is going to make the decision,” said Thomas Krumpter, former Nassau County police commissioner.

Rather than face a ruling by then-Commissioner Edward Webber, Althouse chose arbitration. The case was assigned to Daniel Brent, a professional arbitrator and mediator who charges $2,000 per day to preside over hearings, according to his listing on the website of the Cornell University labor relations school.

County lawyers asked Brent to order Althouse dismissed from the force.

They argued that Fedden “would be alive today” if Althouse had made an arrest “because Fedden would not have been able to take his mother’s car so soon after the first accident and crash it into a wall with fatal consequences,” Brent wrote.

The lawyers cited the level of alcohol found in Fedden’s blood as evidence that he had been driving while intoxicated; pointed to Fedden’s reported statement, “I’m drunk. I’m drunk”; and informed Brent that police department procedures called for subjecting Fedden to sobriety testing based on the dispatcher’s notification of possible intoxication.

In his defense, Althouse testified that he saw no evidence Fedden was intoxicated. Supporting Althouse’s account, the PBA submitted a sworn statement obtained from a witness who lived across the street from the crash site. The witness’ name was blacked out in the internal affairs file.

“The driver did not appear to me to be under the influence of alcohol or impaired in any visible way,” the witness wrote, also stating that Fedden appeared to be “composed, calm, lucid, and spoke clearly.”

Interviewed by Newsday, Rupnick, the chiropractor, said that he gave the PBA a statement for use in the arbitration hearing in which he said he had seen no evidence of intoxication.

Based on the two statements that Fedden appeared sober — one by Althouse, one by the witness — Brent found that Althouse had no grounds to suspect that Fedden had been drinking.

He also wrote that Fedden’s blood alcohol level “did not demonstrate persuasively” that Fedden had shown signs of intoxication.

Finding that the county failed to establish a personal relationship between Althouse and Fedden, Brent concluded both that Althouse knew Fedden “only casually as the owner of a local sandwich shop and that there was no reason to think favoritism influenced Althouse to spare Fedden from taking a field sobriety test.”

He also excused Althouse’s failure to subject Fedden to testing as ordered by regulations.

While acknowledging that “police protocol mandates” sobriety testing after a dispatcher relays that a driver may be intoxicated, Brent wrote that the county had failed to prove that Althouse had “improperly” failed to follow the rule. Instead, he wrote that Althouse’s observations of Fedden “operated as an informal field assessment of the driver’s sobriety.”

Suffolk police protocols do not include an “informal” field sobriety test, Powers said.

‘If it is subjective, and a police officer can come up with his own informal investigation, then what are we doing?’

John Powers, attorney who specializes in DWI casesPhoto credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

“Their language is pretty formal and doesn’t leave room for interpretation,” he said, adding, “What’s an informal field assessment? What, in fact, would that mean? If it is subjective, and a police officer can come up with his own informal investigation, then what are we doing?”

After remarking on Althouse’s “impeccable record of service,” Brent dismissed the department’s charge that Althouse had failed to perform his duty by not testing Fedden.

Brent also dismissed the department’s second charge — that Althouse had not mentioned Fedden’s two passengers in his crash report.

He concluded that Dimonte and Nigro left the scene before Althouse arrived five minutes after the 911 call — an account that conflicts with Dimonte’s memory of seeing Fedden in the backseat of the police car that drove him away.

Asked about the third charge — that he had transported Fedden without notifying a dispatcher — Althouse told Brent that he couldn’t remember what he had done. Brent wrote that notifying a dispatcher would not have changed the outcome for Fedden and accepted the PBA recommendation that Althouse should be subjected to counseling by the department.

After the arbitrator ruled that the county had not produced evidence that Fedden was drunk, the department withdrew the charge that Scaduto had failed to supervise Althouse.

It is not uncommon for arbitrators to reduce proposed punishments for police, said Stephen Rushin, associate professor of law at Loyola University Chicago who has studied police arbitration. But reducing a punishment from termination to counseling is “fairly dramatic,” he said.

“If you’re unable to consistently discipline officers and have that discipline stick, that makes organizational change and reform hard. It also makes it difficult to deter future wrongdoing,” he said in an interview.

Adler, who has studied arbitration in police discipline, said, “If I was in that community, I would be scared … that this is the way the world works.”

Michael Caldarelli, who oversaw the department’s investigation into the case as commanding officer of the Internal Affairs Bureau at the time, said he viewed the case as “very cut and dried.”

‘I stand by the IAB report. Am I perplexed by the arbiter’s finding? Yes.’

Ex-Suffolk internal affairs commander Michael CaldarelliPhoto credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

“I stand by the IAB report. Am I perplexed by the arbiter’s finding? Yes,” he said.

Brent declined to discuss his decision.

“The arbitrator’s decision speaks for itself. It is not appropriate for an arbitrator to speak further,” he said.

Anonymous calls and PBA cards

In her lawsuit against Ruby Tuesday, Fedden’s mother alleged negligence and reckless disregard for allegedly serving Fedden two 16-ounces glasses of Jack Daniel’s whiskey and coke, with at least 10 ounces of alcohol in each glass. She recovered an undisclosed amount.

Kathi Fedden’s suit against the police department alleged, among other things, negligence and reckless misconduct. Her complaint said police “conspired to avoid charging Peter with any crime due to their knowledge of Peter and his generosity to them through his deli.”

She settled the case against the police department for a payment of $1,500.

After speaking with Newsday in a brief interview, Kathi Fedden said she did not wish to discuss the case any further.

Thomasson, the lawyer who represented her, said that she had received anonymous phone calls about the suit and that notes accusing her of being “anti-cop” had been left on her windshield. He said she settled because she wanted to move on with her life.

He added that Kathi Fedden turned over to him a two-inch stack of PBA cards that officers had given to Fedden for use if police ever pulled him over.

MORE COVERAGE

Reporter: Sandra Peddie

Editor: Arthur Browne

Video and photo: Jeffrey Basinger, Reece T. Williams, Chris Ware

Video editor: Jeffrey Basinger

Graphics: Jeffrey Basinger, Gustavo Pabon, Andrew Wong

Digital producer, project manager: Heather Doyle

Digital design/UX: Mark Levitas, James Stewart

Social media editor: Gabriella Vukelić

Print design: Jessica Asbury

QA: Daryl Becker