After 33 years in prison new findings may clear his name

Keith Bush was convicted of the murder of an LI teen in 1976. He’s always said he was innocent — and now, new evidence shows Suffolk authorities kept secret that another man should have been a suspect.

Editor’s note: Since this story was published a Suffolk judge vacated Keith Bush’s conviction as a result of a joint application from his lawyer and Suffolk District Attorney Timothy Sini. Bush is no longer a convicted murderer or a registered sex offender.

An innocent man.

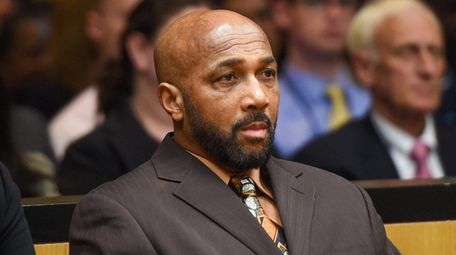

For the past 44 years, Keith Bush has made that claim to anyone who’d listen — ever since he was accused and convicted of a 1975 Suffolk County sex-related murder.

At every step in his long journey through New York’s criminal justice system, Bush insisted he didn’t commit this crime and that the real killer had gotten away.

“I always felt that they were hiding something,” he says of Suffolk’s original homicide investigation against him. “That they weren’t telling us something, that something was wrong.”

Bush was a 17-year-old junior at Bellport High School when Suffolk authorities charged him with killing Sherese Watson, 14, after a late-night house party in North Bellport. Watson’s body — strangled and stabbed — was later found in an empty lot full of weeds not far away from the party.

Despite his claims of innocence, a jury in 1976 found Bush guilty of murder and attempted sexual abuse after what was then called the longest criminal deliberation in Suffolk history. Bush would spend 32 years in jail until paroled in 2007, and an additional year for a later parole violation.

Now 62 and living in his mother’s house in Connecticut, Bush has spent his entire adulthood trying to show he was wrongfully accused and that his conviction should be overturned.

Without success, Bush and his lawyers have made several attempts to exonerate him over the past four decades. They pointed to male DNA evidence found on Watson’s body that wasn’t from Bush, a key witness who recanted, and claims that his signed confession resulted from a police beating.

But now, after gaining his freedom on parole, comes perhaps the most extraordinary twist in Bush’s effort to clear his name — newly revealed evidence showing that former Suffolk authorities kept secret another potential murder suspect in Watson’s killing.

Prompted by a Freedom of Information lawsuit against Suffolk police by Bush’s lawyer, authorities released never-before-seen 1975 documents, disclosed between October 2017 and May 2018. The evidence included a signed written statement by John W. Jones Jr., placing himself directly at the scene of the Watson killing.

In his statement, Jones told Suffolk authorities that after leaving the same North Bellport house party attended by Watson on Jan. 10, 1975, he stumbled drunkenly over the girl’s body in the empty lot. He also said a long black plastic comb, found beside Watson’s body, “looks just like the one” he dropped at the murder scene.

“I tripped over a girl. I know it was a girl because of her hair, ” said Jones, who never alerted police to the corpse he fell over. “Sometime after the girl was found and murdered I saw her picture in newspapers and in church. I recognized her as a girl I saw at the party.”

Other newly released documents show Suffolk’s then top homicide prosecutor arranged shortly afterward for two lie-detector test for Jones, including one given by a renowned New York polygraph expert in July 1975. According to a report based on that later exam, Jones acknowledged tripping over Watson’s body, but showed “slight indications of truthfulness” when he denied choking the young girl to death. The report does not explain what that means.

Yet Jones remained a mystery man in the Watson case for the next four decades.

Neither his signed written statement nor the polygraphs from Jones — both obtained by police and prosecutors before Bush’s 1976 trial and conviction — were ever revealed publicly by Suffolk authorities. These documents would remain unknown to judges overseeing the case as well as Bush and his attorneys.

This new evidence would have had a dramatic impact on Bush’s fate had it been revealed at his 1976 trial, said Harold Seligman, Bush’s former defense lawyer.

“When I heard about the Jones disclosure, I was shocked,” Seligman said. “I always thought my client was innocent. So of course, I think the real killer got away. And I think there’s a strong possibility that it could have been Jones.”

Bush’s current lawyer, Adele Bernhard, said the undisclosed facts about Jones and other important facts demand that the Bush conviction be thrown out.

“Keith Bush served 33 years in prison wrongly convicted of a crime he did not commit,” said Bernhard, a New York Law School adjunct professor who heads its Post-Conviction Innocence Clinic and has worked on the Bush case for the past decade. “New evidence proves his innocence.”

At Bernhard’s request, a Suffolk County Conviction Integrity Bureau — created last year by District Attorney Timothy Sini to review possible wrongful convictions — is investigating the newly disclosed evidence in the Watson murder. It will decide whether to join Bernhard in asking a judge to vacate Bush’s conviction.

If all sides agree with Bernhard, it would be a stunning turnaround for the Suffolk DA’s office, which for the past four decades has insisted on Bush’s guilt and fought any claims of innocence or official wrongdoing in the case.

If Bush’s murder conviction is thrown out — 44 years after he was first charged — it will become one of the longest-running “innocent man” homicide cases in both New York State criminal history and modern American jurisprudence, according to records and experts.

“In the event that we determine he should be exonerated, that would be an extraordinary amount of time for anyone to suffer under a conviction if they are, in fact, innocent,” said Howard S. Master, who heads the Conviction Integrity Bureau, which is reviewing the Bush case. “That would be deeply disturbing.”

At least one surviving member of Sherese Watson’s family still believes that Bush killed the young girl.

“Based on the evidence, it looked like he (Bush) did it,” recalls Fred Veale, Sherese’s uncle. “He was upset that she (Sherese) wouldn’t do what he wanted.” Veale, who lives in Florida, says he didn’t know about the newly disclosed evidence in the case and declined to comment further.

But Bush and his lawyers said he has suffered a grave injustice that may finally be righted. They say the hidden evidence of another potential murder suspect in the case forced Bush to spend most of his life in prison.

‘They were trying to make it look like I was responsible for committing this crime … they had someone at the crime scene and they hid it for 40 years.’ -Keith Bush

“They were trying to make it look like I was responsible for committing this crime,” said Bush, who is still listed on the internet as a sex offender because of his 1970s conviction. “In fact they had someone at the crime scene and they hid it for 40 years.”

The Bush case illustrates several long-running criticisms of Suffolk’s methods of investigating and prosecuting murders dating to the 1970s. It also raises major ethical questions about former police and prosecutors who knew about Jones and did nothing.

And if Bush’s conviction is overturned, it would be another reminder of a controversial past for Suffolk authorities that in this decade has included a conviction of official wrongdoing by the former police chief, James Burke, and pending federal charges of corruption against the former District Attorney Thomas Spota and his top aide.

Based on hundreds of court documents, sworn affidavits, volumes of testimony — as well as videotaped interviews with several key figures in the case — Newsday found:

- Failure by Suffolk authorities to follow legal rules with crucial evidence. During Bush’s trial, Suffolk’s prosecutor and police did not mention Jones. Despite a Supreme Court ruling, Brady vs. Maryland, calling for disclosure of exculpatory evidence to defense lawyers, Suffolk Assistant District Attorney Gerard Sullivan and top homicide detective Dennis Rafferty never mentioned the Jones polygraph test and signed police statement that they knew placed Jones at the scene of Watson’s murder.

- DNA evidence pointing to another suspect other than Bush was dismissed or ignored. A 2006 test of human tissue found underneath Watson’s fingernails revealed genetic evidence from another unknown male, but not any from Bush. A decade ago, Bush’s appeal of his 1976 conviction based on the new DNA tests was opposed by the then-Suffolk DA and rejected by a judge. Until the recent review, Suffolk authorities never tested the available DNA of Jones to see if he might be Watson’s killer.

- The key prosecution witness in Bush’s trial later recanted and is now part of the effort to clear his name. Fourteen-year-old Maxine Bell was crucial in implicating Bush in Watson’s murder but now says she was “scared” of Suffolk police when she lied on the stand in 1976. Her claim was rejected by a judge in 1981. Now a grandmother, Bell has apologized to Bush for what she said was her false testimony and has signed an affidavit in Bush’s new effort to vacate his conviction. “I knew my testimony was not true when I testified at the trial,” she said.

- Allegations of police coercion and forced admissions. During his trial, Bush insisted he was beaten by police during a lengthy interrogation and forced to sign a statement confessing to Watson’s murder — wrongdoing that police adamantly denied. Rafferty — the key investigator in Bush’s case — was later criticized in a 1989 state investigation commission report for questionable testimony and confession-taking methods used in other Suffolk murder cases similar to the Bush case. In Bush’s current appeal, other witnesses say they were coerced as teenagers into making false statements or that their accounts favorable to Bush were twisted or ignored by police.

- Past conflict of interest by Suffolk’s former District Attorney. Bush’s lengthy attempts to exonerate himself with DNA evidence from 2006-2011 were vigorously resisted by then-Suffolk DA Thomas Spota. Bush’s lawyer now says Spota should have considered recusing himself because of his past associations with both prosecutor Sullivan and Det. Rafferty and the controversy surrounding their actions in this case. Prior to becoming DA, Spota had been a private law partner with Sullivan, who died in 1993, and also a lawyer for the Suffolk Detectives Association. In an interview, Spota denied knowing anything about the Bush case or any possible need for recusal. “If I didn’t know anything about it, how could I recuse myself?” Spota said.

- Years of extra time in prison for Bush who constantly claimed that he wasn’t the killer. By insisting on his innocence with state parole officials, Bush’s lawyers say he stayed in prison by as much as an extra 12 years. Bush was eligible for release starting in 1994, under terms of his 20 years to life sentence. But repeatedly before state officials, Bush refused to admit any responsibility for Watson’s murder, a key requisite for getting released on parole. As part of his effort to clear his name as a convicted sex-related murderer, Bush also passed a privately administered lie-detector test, which found he was “truthful” when he denied murdering Watson. A copy of that report was provided to DA Sini’s office as part of their review.

- Doubts among the jury during long-running deliberations. At least one juror who voted guilty in Bush’s trial now says that learning about Jones, the other potential suspect, “would have made difference” in the outcome if disclosed by Suffolk authorities. “It would have led to doubts,” said Lore Barbier of Bellport, recalling the lengthy jury deliberations. “And we would have had doubts like ‘Maybe he didn’t do it’.”

- Destroyed murder weapon.Though strangled, Watson’s body was found riddled with many small puncture wounds on her back. Suffolk authorities said at Bush’s trial that these wounds resulted from his attack during Watson’s strangulation with a metal Afro comb that they later recovered at Bush’s North Bellport home. However, several years after the 1976 trial, police said they lost the metal comb, an alleged weapon used in the murder, which was destroyed and can no longer be found in their files.

- Tale of two combs. While the metal comb played a prominent role in Bush’s trial, the legal significance of another comb — a black plastic pick found at the murder scene — would remain unknown to Bush and his attorneys until recently. Only last year when Jones’ 1975 written statement to police was finally revealed by the current DA’s office — in which Jones identified the black plastic pick as the one that likely fell from his pocket when he tripped over Watson’s dead body — did this second comb take on greater meaning for Bush’s lawyers and Sini’s team investigating the case.

- If not Bush, who killed Sherese Watson?If Bush is exonerated, the real killer in the Watson case may never be caught or punished. Jones later committed felonies in the 1980s, including a knife assault outside an Amityville bar, but died in 2006 in Pennsylvania at age 52 while Bush was still in prison.

During a six-month investigation, Newsday attempted to contact all of the main surviving characters in this courthouse drama, including Bush, other witnesses, the top homicide detective, the victim’s family, and the 83-year-old judge who presided over his trial.

In addition, Newsday followed inside the DA’s team of investigators headed by Master as they examined the evidence in the case, including some new DNA findings, investigated potential official wrongdoing in the Bush murder conviction, and ultimately tried to determine whether an innocent man had spent much of his life unjustly in prison as a sex killer.

This is the story of Bush’s 44-year fight to prove his innocence.

Night of the party

The small ranch-style house on Bourdois Avenue in North Bellport reverberated with loud, thumping sounds of 1970s music. Inside were more than 50 partygoers, most of them Bellport High School students like Sherese Watson and Keith Bush.

On this Friday night in early January 1975, the weather was unseasonably warm. To get into the party, visitors paid 50 cents admission and 65 cents for beer and soft drinks. Others brought their own pot.

When the house got too steamy from people dancing, some like Keith Bush went outside to cool off and chat with friends. That’s where Bush said he first saw Sherese Watson approaching the front door.

“We had a little basic conversation,” Bush recalled in an interview. “She asked, like, who was in there? How was it in there? That type of stuff.” Bush said he was friendly with Watson and followed her into the party.

Watson was a freshman, who that night wore stylish jeans, a white turtleneck sweater, and a gray and white furry coat called a rabbit jacket. Two years earlier, Sherese’s family had moved from Brooklyn to North Bellport, living in a predominantly black community carved out of farmland, like much of suburban Long Island.

“I moved out here because I wanted a better environment for my children,” her mother, Sherry Young, explained at the time. But Sherese missed her life in the big city. “All the time she said she wanted to move back to the city,” Brenda Carlos, a friend who came to the “pay party” that night with Watson, said in a 1975 Newsday interview. “It was too quiet for her.” Unlike Watson, the family of Keith Bush had deep roots on Long Island. His mother’s heritage traced back to the Shinnecock tribe on the East End.

Bush liked his life in Bellport and made the high school’s freshman basketball team as a guard. But when his parents separated, Keith spent his sophomore year going to school in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where his father’s family lived. For his junior year, he returned to Bellport to live with his mother and other siblings.

On the night of the party, Bush said he chatted briefly with Watson inside the house.

“At one point, she came over and was telling everybody, ‘I’ll see you later’,” he recalled. “And she said, ‘I’ll see you later, Keithy!’ and she walked out the front door. But I didn’t know that would be the last time I would see her.” From this point, Bush’s version of what happened that night would differ dramatically from what became the official Suffolk police account.

Bush would testify that he didn’t leave the party until much later, around 3 a.m., and left with some male friends, heading north from the house on his way home to eventually go to sleep.

One witness said they saw Sherese leave earlier in a red car with other teenagers and drive off. Another teenage girl, Watson’s friend Brenda Carlos, told police that Sherese expressed her intent to walk home with Bush, though she didn’t see her leave with him. Bush “seemed to be the only guy she was talking to most of the night,” Carlos said to police.

But a key witness, Maxine Bell, gave a crucial statement to police, saying she watched Bush and Watson depart the party together. They headed south toward Brookhaven Avenue, Bell said, and she saw Bush walking with his arm around Watson.

The Saturday morning after the party, Watson’s mother reported her missing. Her worried family waited in vain, hoping Sherese might have stayed at a friend’s house and would show up soon.

But on Sunday, Jan. 12, her body was found by two children passing through an empty lot, about three blocks from where the party took place.

Based on her wounds and her tattered clothing, authorities determined that Sherese had been choked to death and that her attacker had attempted to sexually abuse her.

Word of Sherese’s murder spread quickly around the neighborhood, reaching an outdoor basketball game where Bush had been playing with friends. They all rushed to the scene, he said.

Bush watched as Sherese’s dead body was taken away by Suffolk authorities. “You get overwhelmed by seeing something like that,” he remembered. “I never imagined anything like that in my wildest dreams. So I was really sad and couldn’t understand why somebody would kill her. I really couldn’t understand it.”

Before Watson’s body was found, Suffolk officers had stopped by his family’s house and asked him if he had left the party with Sherese. With his mother by his side, Bush said no and offered to help in the search, having no idea he might be under suspicion.

“They were just trying to find out more information that they could go by to find other people who would provide some answers as to why she didn’t come home,” he recalled. Before long, it became clear Bush was the police’s leading suspect.

The confession

On Tuesday, Jan. 14, 1975, Suffolk Det. Dennis W. Rafferty returned to work, two days after Watson’s body was discovered.

During his time away, he’d not been involved in the North Bellport homicide investigation and sought to quickly catch up. The police had made little progress.

“We were finding it a little difficult knocking on a few doors. We were getting nowhere,” Rafferty later testified at a Bush pretrial hearing. “Sometimes — we’ve experienced in black communities you don’t get the greatest cooperation.” All the principles in the case were black.

A sandy-haired man in his 30s, Rafferty favored a more informal style than most cops, dressing more like a tweedy junior professor than a street cop. He brought an intensity to his work that other detectives and prosecutors said they admired but that critics said could be controversial.

Over the years, Rafferty would become involved in some of Suffolk’s most high-profile investigations — such as the so-called “Amityville Horror” murder case of defendant Ronald DeFeo Jr. Later on, as a detective investigator for the Suffolk DA, Rafferty worked on the kidnapping case of victim Katie Beers, the 9-year-old girl found alive in an underground bunker after she held hostage for 17 days by her captor who was then a neighbor.

In the Watson murder, Rafferty quickly canvassed other police working the case. Based on what he heard, Raffety later testified, he soon came up with the theory that Bush did it. As he later attested, Rafferty placed great weight on the statement taken from Maxine Bell, the only person to claim she saw Bush and Watson leaving the party together.

Later that Tuesday afternoon, police managed to get Bush taken out of Bellport High School with the help of a local community leader. They transported the teenager to a local precinct station and eventually to the homicide squad offices located then in Hauppauge, a short distance from the county legislature building.

For the next several hours, the teenager was questioned alone about the Watson murder without a lawyer present or his mother told of his whereabouts, court records show.

“I never was involved in the criminal justice system, in no way whatsoever,” Bush recalled. “I mean you see police but you’re taught … you respect them. They’re basically extensions of your parents. They tell you what to do whatever. And you’re taught to believe that they have your best interests at heart.“

What happened inside the homicide squad room that night became another point of sharp difference.

Rafferty and other detectives said they conducted their examination of the teenager by gaining his confidence until he finally confessed.

“I said, ‘I don’t think you wanted to kill her’,” Rafferty later testified at trial about his questioning of Bush. “I don’t think you took her there to kill her,’ and he said, ‘I didn’t mean to. Do you believe me?’ and I said, ‘I do believe you. I do believe you’.”

According to Bush’s written confession taken by Rafferty, the teenager admitted to strangling Watson when she screamed and resisted Bush’s sexual advances. And when Watson tried to pull away, the statement said, Bush pulled from his pocket a “pick” — later identified as a metal comb with a wood handle — and stabbed Watson repeatedly in the back with it.

The police statement, signed by Bush, says he was advised of his legal rights and waived the chance to have a lawyer present during questioning.

But Bush says he never confessed, insisting on his complete innocence. He describes the police interrogation as nothing short of torture.

According to Bush, Rafferty grabbed the teenager by the legs and kicked him in the groin, while others detectives beat him on the head with a thick telephone book.

“They were basically telling me that ‘We know you committed this crime,’ that you need to admit to that,” he recalled. “I kept telling them that I didn’t commit this crime.”

After several hours, Bush said, he finally signed a police statement — notarized by Rafferty — only because he feared more beatings. “Detective Rafferty, he was writing stuff,” Bush remembers about the three-page confession. “I never knew what the statement was. I never knew what I signed. I just know that I signed something to stop them from assaulting me.” Under questioning by the prosecutor at a pretrial hearing, Rafferty denied that Bush was “struck, hit, kicked, beaten or threatened in any way.”

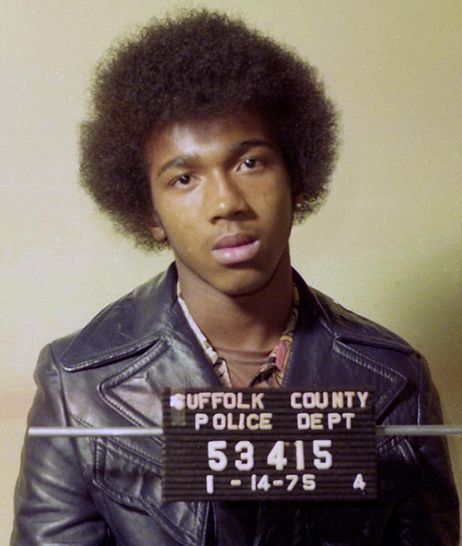

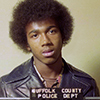

Keith Bush’s mugshot. Credit: SCPD

Booking photo of Keith Bush from 1975. Photo credit: SCPD

With Bush’s signed confession, the teenager was charged with murder and spent the night in jail — the beginning of more than three decades spent behind bars.

In years to come, Rafferty’s methods as a Suffolk homicide detective would be questioned by both judges and an outside state investigating panel.

In 1981, the New York Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, overturned a Suffolk murder conviction because Rafferty and another detective improperly took a confession from a defendant without contacting his lawyer from a pending case. That controversial decision, which required Suffolk to retry the case, effectively expanded rights for suspects questioned about crime in New York State.

And in 1989, the New York State Temporary Commission of Investigation determined that accounts of Rafferty’s alleged confession taken from a defendant in another 1985 murder case was “highly suspect” and created enough doubt to lead to a jury acquittal. “Rafferty’s convenient talent for producing crucial testimony and evidence at the 11th hour in homicide prosecutions disturbs the Commission,” said their report.

Rafferty declined to be interviewed for this story, according to his lawyer, James O’Rourke. Records show he was transferred out of the homicide squad in 1986 and retired in 1997.

But when he took Bush’s confession in January 1975, Rafferty was someone who had seemingly pieced together a homicide puzzle when other police had failed, court records show. In Rafferty’s hands, on his first day back to work, the whodunit murder case of Sherese Watson appeared solved.

The other potential suspect

Three months after Bush was jailed, Suffolk authorities came across a disturbing finding that seemed to throw the whole Watson murder case into doubt.

On May 9, 1975, Rafferty and other detectives took a statement from another suspect, John W. Jones Jr., that placed him at the murder scene at the same time the teenage girl was strangled.

Documents recently made available shed some light on how Jones came to the attention of homicide investigators.

Around that time, on Friday night, April 18, 1975, Jones was caught riding in a stolen Chevrolet Monte Carlo with two other men, records show.

Starting near the Wyandanch train station, Suffolk cops pursued the trio until the late-model muscle car crashed along Straight Path and Deer Park Avenue in Dix Hills. The driver was hospitalized and later arrested for burglary. Police charged Jones and the other passenger with unauthorized use of a vehicle, a misdemeanor.

The April 1975 arrest report, obtained by Newsday through a Freedom of Information request, shows that fingerprints were taken from Jones. Existing records do not show precisely how Jones, in a few short weeks in 1975, went from a minor crime to becoming a potential suspect in Watson’s killing.

However, with Bush awaiting trial, Jones raised a number of troubling concerns for Suffolk homicide investigators.

Unlike Bush, who denied any involvement with Watson after she left the party, Jones admitted to stumbling over the girl’s body in the weedy lot where she was found.

And unlike Bush, who had no previous record, Jones, then a 21-year-old woodworker, had a Suffolk rap sheet of burglaries and other crimes dating to 1970. The police report resulting from the stolen car crash summarized Jones’ previous convictions and arrests as “too many to list.”

By May 9, 1975, Jones had put himself directly in the center of the Watson murder probe. According to his police statement, Jones attended the January 1975 teenage party at Bourdois Avenue and left between 1 and 1:30 a.m. — about the same time the Suffolk medical examiner estimated Watson died.

Jones told police he was drunk, didn’t feel good and threw up along the street.

Then on his way home to his sister’s house, Jones said he cut across a dirt pathway and tripped over Watson’s body. A long black plastic comb fell out of his pocket and was left near the girl’s remains.

“I didn’t recognize her at the time,” Jones said in the statement. “After running away from the girl, I went home to my sisters [sic]”.

Why Jones didn’t alert anyone that night or call the police the next morning isn’t addressed in this police statement. Nor is it clear how Rafferty and the other detectives learned of Jones or what compelled him to give the statement three months later.

“On May 9, 1975 I came to the Suffolk County Police Department Homicide and was shown a photograph of where the girl I tripped over on January 11, 1975 was found,” the Jones statement read. “In the photograph I saw a pik [comb] that looks just like the one I had.”

On a piece of paper, Jones drew a small map for Rafferty of where he had traveled after leaving the party. He signed and initialed both the map and crime scene photo.

Staring at the dead girl’s police photograph also seemed to stir Jones’ memory about seeing Watson at the party that night.

“I remember her leaving the party about one hour ahead of me, or maybe a half-hour,” the statement said.

With Bush already in jail awaiting trial, the statement prompted Rafferty and Suffolk Assistant District Attorney Gerard Sullivan to seek a lie-detector test for Jones, to help judge his veracity.

On July 7, 1975, Rafferty and another detective escorted Jones into Manhattan, where he was connected to a polygraph machine. Richard O. Arther, then a leading expert in the country, conducted the exam at his firm called “Scientific Lie Detection.”

According to Arther’s confidential polygraph report later sent to Sullivan, “The main issue under consideration was whether or not Mr. Jones was telling the truth when he claimed that he had no guilty knowledge of nor had he participated in the murder of Sherese Watson.”

During his exam, the polygraphist asked Jones three basic questions:

- Did you see Sherry Watson get choked to death?

- Did you choke Sherry Watson to death?

- Did you see Sherry Watson get hurt?

Jones showed “slight indications of truthfulness” when he answered “No” to all three questions, according to the polygraph report. Experts told Newsday that Arther’s nebulous phrase — “slight indications of truthfulness” — would likely result in an inconclusive finding today.

The same level of veracity was shown when Jones replied “Yes” to the question — “Did you really stumble across Sherry Watson’s body as you walked home?”

To overcome any lingering doubt, the polygraphist Arther gave Jones one final open-ended multiple choice question — “Did you stab Sherry [sic] Watson in the back with a _____? “.

There were seven different choices and Jones answered “No” to each.

However, the lie-detector expert seemed to have mixed up a key piece of evidence.

According to the polygraph report, Jones was quizzed about a metal pick comb. But Arther apparently didn’t know the difference between the metal pick linked to Bush, the black plastic comb found beside Watson’s body that Jones identified as his own, nor any other possible weapon that caused the wounds.

“On two separate tests, Mr. Jones did NOT react to the choice known to be true — ‘metal hair pick’,” the report concluded. “Therefore, this is an additional indicator of truthfulness when Mr. Jones denies any guilty knowledge or participation” in the Watson case.

In fact, the metal pick confiscated at Bush’s home was the one that police said was used by Bush in the fatal Watson attack. It’s not clear from the polygraph report if Jones was ever asked about the black plastic comb found at the murder scene.

Jones proved to have remarkable good fortune for a man being questioned by police about a sex-abuse killing. Without a defense lawyer by his side, he had signed a statement placing himself at the scene of Watson’s murder. Yet he was never charged.

After his lie-detector test, Jones went home on his own. And on Sept. 11, 1975, the misdemeanor charge resulting from his wild ride in the stolen car that crashed in Dix Hills was dismissed on a motion by the Suffolk DA.

There wouldn’t be any further investigation about his part in the Watson murder for another four decades.

However, in the years ahead, John W. Jones Jr. would be no stranger to Suffolk police. Nor to violence against women.

Three years after Watson’s strangulation, police arrested Jones following “an altercation” with a woman described as his girlfriend, records show. In July 1978, Jones was charged with criminal mischief for kicking in the door frame of the woman’s North Amityville home. He later pleaded guilty to a reduced harassment charge and given a conditional discharge.

With another woman in January 1984, police said, Jones punched her in the face, lacerating her nose and leaving her head swollen.

Jones, by then 30 years old and living in North Amityville, was charged with third-degree assault, a felony, but later pleaded guilty to misdemeanor harassment and given a $100 fine.

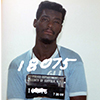

A 1984 booking photo of John W. Jones Jr. Credit: SCPD

A 1988 booking photo of John W. Jones Jr. Photo credit: SCPD

A few months later, in July 1984, Jones and a Brooklyn man were charged with robbery and assault with a knife outside a bar called Poppa T’s in North Amityville. The victim in that attack, Anthony Wrublasky, suffered several knife wounds.

“They were really vicious,” said his wife, Joann Wrublasky. “He was lucky to be alive.”

Anthony Wrublasky declined to comment, but his wife said they were unaware that Jones had been a police suspect in the 1975 Watson murder. “I didn’t know anything about this,” she said.

As part of that 1984 robbery and assault case, the then-Suffolk DA asked a court to require Jones to give a blood sample so it could be analyzed and compared with stains on the victim’s clothing and the knife used in the attack. “The amount of blood required is small” for the lab analysis, the DA said in November 1984.

Soon Jones’s defense lawyer, Kevin Fox, consented to the blood samples. And in February 1985, the Suffolk DA agreed to let Jones plead guilty to a reduced charge and receive a 1-year jail term.

In an interview, Fox said he doesn’t recall the 1984 case but said it was likely that the plea bargain resulted after blood samples were taken.

Earlier this year, Suffolk prosecutors confirmed the crime lab had kept the Jones blood samples stored since the 1984 incident. Until then, no Suffolk investigator had ever checked to see if the Jones blood sample might match the unknown male DNA discovered under Watson’s fingernails a decade ago.

Meanwhile, Jones’s criminality on Long Island continued. In 1988, Jones, then living in Wyandanch, was charged with two drug felonies — sale and possession of a controlled substance.

Police arrested Jones in the same North Bellport neighborhood where Watson’s murder occurred a decade earlier. Jones pleaded guilty to a reduced charge and was given a prison sentence of 2 to 4 years.

Despite all his criminal activity, however, there is no reference in available police records to the fact that Jones had been a homicide suspect in 1975. Even though Jones had stumbled over Watson’s body and left his plastic comb at the scene, his polygraph test results apparently satisfied prosecutor Sullivan and Suffolk detectives.

Jones would remain a mystery in the Watson murder case for many years, his presence never disclosed by the small circle of Suffolk authorities who in 1975 knew and kept this secret.

Instead, they decided to proceed with their prosecution of Keith Bush.

The trial

After more than a year behind bars, Bush went on trial in March 1976. “The event was overwhelming,” Bush recalled of the intense proceedings. “I was just really frightened, trying to maintain my composure and prepare for whatever the outcome would be.”

Bush’s private defense attorney Harold Seligman recalls being impressed how the 18-year-old client handled this ordeal.

“What struck me most about Keith was that he never, ever wavered in his proclamation of being innocent,” Seligman recalled. “There was never a time that he ever told me that he did this, or had anything to do with it. And I believe him.”

During the trial, prosecutor Sullivan presented damaging forensic evidence, including a police technician who testified that fibers found under Watson’s fingernails were identical to those on Bush’s jacket that night. A medical examiner official said the puncture marks found on Watson’s back were a match with the first three tines of the metal comb linked to Bush.

The prosecutor also called to the stand Watson’s mother, who testified how she visited Bush’s home when Sherese was missing and how he denied knowing what happened to her.

But the most damning evidence was Bush’s signed statement to police and testimony from 14-year-old Maxine Bell. She swore she saw Bush and Watson leaving the party house together in an embrace. “They were hugged up,” recalled Bell, without remembering many other details.

Nothing was mentioned about Jones. Neither prosecutor Sullivan nor Rafferty disclosed the police statement and follow-up polygraph of Jones that they had arranged months earlier.

“Officer, were there other suspects on the day you interviewed my client?” defense lawyer Seligman asked Rafferty during the trial.

Prosecutor Sullivan immediately objected.

What followed was another pivotal moment in Bush’s case.

At a sidebar with the judge, with the jury excused, Sullivan discounted any murder suspects other than Bush. The prosecutor assured the judge that Rafferty was prepared to testify about others who were questioned “but there was nobody else who was connected with the crime with any evidence.”

Then Sullivan indicated to the defense lawyer that if he persisted in this line of questioning, he would be free to ask Rafferty what incriminating things those questioned might have told police about Bush. Seligman said he wasn’t willing to risk further damage to Bush’s defense by doing so.

At that time, Seligman recalled in an interview, he had no inkling about Jones. And there’s no indication that trial Judge Melvyn Tanenbaum knew anything about the existence of Jones. So the police statement and polygraph from Jones remained a secret.

Looking back at this exchange, Bush’s current appeal lawyer Adele Bernhard said then-Suffolk authorities deliberately deceived the court.

“At trial, the state falsely permitted Detective Rafferty to deny that police investigated any other suspects besides Bush,” said Bernhard. “Rafferty was permitted to leave the impression that there were no other suspects. The state did nothing to correct that impression.”

Now retired as a judge, Tanenbaum, 83, said he remembers little from the Bush trial.

“I found it imperative to preside over a fair trial and let the evidence speak for itself,” he told Newsday.

Defense lawyer Seligman said he never had a clue about Jones. “Nobody heard that Detective Rafferty did indeed know there was” another potential suspect, Seligman recalled in an interview. “Nobody knew that at the time and they didn’t know about it until 2018 — 40 years later.”

Instead, at the 1976 trial, Seligman challenged the Bush confession taken by Rafferty and other Suffolk detectives, putting Bush on the stand to claim it was the result of a police beating.

On cross-examination, prosecutor Sullivan grilled Bush about details of the alleged physical threats. If there had been a police beating, Sullivan challenged the teenager to provide a blow-by-blow account.

“How many times were you hit?” the prosecutor insisted.

Bush said he didn’t know.

“Well,” Sullivan volleyed back, “can you tell us whether it was once or twice or three times?”

“It was a lot of times,” Bush insisted.

“Was it more than 10?”

“Yeah,” Bush said.

Sullivan pushed further. “How many more than 10?”

“I don’t know, I know I — I wasn’t counting,’ Bush replied, “but I know it was a lot of times.” More than 40 years later, the memory of his police interrogation remains vivid and painful. As Bush described this ordeal to Newsday, he burst into tears.

The verdict

Watching this dramatic Bush trial testimony in 1976 was a jury of nine men and three women.

Lore Barbier, now 79, recalled her surprise at being chosen as a juror because she lived not far from North Bellport and worried if she could be objective enough.

During the jury deliberations, Barbier said, the initial vote “went 50 — 50” among jurors. All were white except a black retired Air Force colonel.

Inside the jury room, Barbier said, she always voted guilty. She was convinced by detectives that Bush killed Watson because she rebuffed his sexual advances.

“Listening to the police testimony, we felt he must have done it,” she recalled. “We didn’t think he was violent but this was something that got out of hand.”

Barbier said if the jury had known about Jones, it would have likely led to a possible acquittal for Bush in 1976.

“It surprises me,” she said when told about Jones and asked about its possible impact on the jury’s verdict. “It goes back to what we were presented with.”

After four days of deliberations in April 1976, the jury convicted Bush of murder and attempted sexual abuse. The next day’s Newsday said the jurors “had deliberated longer than any other jury in Suffolk’s history.”

The jury acquitted Bush of a charge of intentional premeditated murder but found him guilty of second-degree murder for killing Watson while attacking her sexually. The judge would later give Bush a 20-to-life sentence for murder and another 0-to-4 years on the attempted sexual abuse charge.

“When they first said ‘not guilty’ of intentional murder, some of the people in the courtroom started clapping and saying, ‘That means he’s coming home’,” Bush recalls.

But from the long faces on the jurors, who didn’t make eye contact with him as they returned to their courtroom seats, Bush surmised that his fate had been sealed.

As the foreman read the guilty verdict, Bush’s family and friends in the courtroom erupted in anger at what they considered a great injustice. Suffolk sheriff deputies had to be called for public protection as court officers ejected three people from the room.

Calling Bush a murderer was more than his family could bear. “They said he was guilty and I went in shock, started getting really upset and screaming, “You’re lying!'” recalled his older brother Mark.

Before the verdict, Bush’s mother, Lorraine Bolling, said she had sought refuge in the ladies room, praying on her knees that somehow her son would be spared.

When she heard noises outside, she rushed to the courtroom door. Exiting were Rafferty, who had composed her son’s confession, and Sullivan, she recalled.

“Rafferty was laughing and he said the DA always gets his man’,” recalled Bolling. “And they started laughing and he walked away.”

Amid the pandemonium, Keith Bush remained calm. “Cool it,” he told his loved ones, raising his two fingers in a peace sign. “We don’t need this.”

Then he was ushered away.

The recantation

After his 1976 murder conviction, Keith Bush moved from the Suffolk jail near his home to confinement in various state prisons, often hundreds of miles away, never staying long in one place.

Time passed slowly, counted in the number of Christmases and other holidays he missed, the weddings and funerals he couldn’t attend. Bush said he felt terribly alone.

“A lot of it is mental torment, mental torture, mental suffering — and that’s where the battle is,” Bush says of life spent in a cell. “Not necessarily in the physical operations of prison life. But overcoming the family getting older, dying on you — you never having the chance to have a real life because the best years of life is literally erased away.”

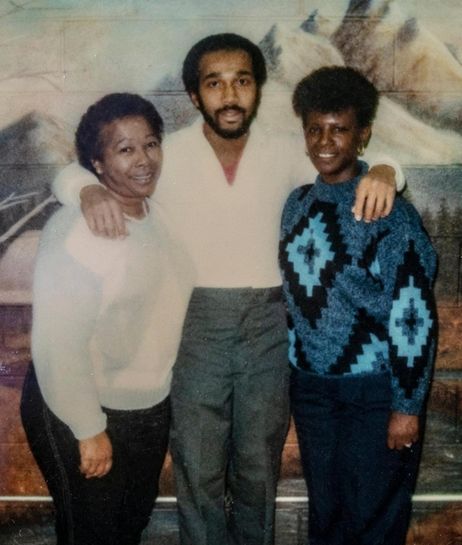

Faded photos from the 1980s and 1990s show Bush’s mother and siblings visiting him behind bars, often with barbed wire or cinder block walls in the background. His mother still keeps a framed graduation portrait of Keith at upstate Green Haven Correctional Facility, dressed in a blue cap and gown after he earned his associate college degree.

Keith Bush, at age 19, in Elmira Correctional Facility in upstate New York. Credit: Bush family

Keith Bush sharing time with his mother, Lorraine Bolling, and cousin Elaine McAllister during a day visit in 1989 in the Eastern Correctional Facility. Photo credit: Bush family

Bush’s brother Mark recalls the long car rides to see Keith in prisons, always careful not to let his real emotions show in the visiting room. The two brothers had grown up together like twins, less than a year apart, sharing the same bedroom as kids.

“I always talked positive because I didn’t want him to feel the pain that I felt,” Mark Bush recalled. “Especially when I was leaving the jail and he couldn’t leave with me. It used to tear me up inside.”

Mark remembers Keith’s remarkable strength and reassurance as an inmate. “You take care of mommy,” Keith told him. “They don’t have my mind — they just have my body.”

Despite the guilty verdict against him, Keith Bush hoped he would prevail through the appeals court process and prove his innocence. His first real chance came in 1980.

In a unanimous decision, the Appellate Division ordered a new hearing to determine if Suffolk police had probable cause to pick up Bush for questioning about Watson’s murder. They wanted to know if Bush’s confession was improperly obtained as the result of “police deception and trickery.”

After five years in prison, Bush said he felt hopeful. If his confession was thrown out, it seemed Suffolk’s conviction against him might fall apart.

The new hearing was held in November 1980 before Tanenbaum, the same Suffolk judge who presided over the original murder trial. While the legality of police questioning was the main issue of the weeklong proceedings, the biggest surprise was the recantation of Maxine Bell.

At the trial five years earlier, Bell, then a 14-year-old girl, testified that she saw Bush and Sherese Watson walking away together from the North Bellport house party on the night of the murder. Bell’s crucial statement to police pointed them in Bush’s direction and eventually led to his questioning and arrest.

But at the new hearing, Bell offered a bombshell — she admitted that she lied at Bush’s trial.

Bell now said she’d never been to the party that January 1975 night and never saw Bush and Watson together. And Bell said she only gave her incriminating statement against Bush because she felt alone and pressured by police after being questioned for hours about the murder.

“I made the statement up,” testified Bell. “I was afraid and scared.”

Four decades later, in a Newsday interview, Bell still says she lied at Bush’s murder trial based on a phony statement to police. Now 59, Bell described herself as a young girl who ran away from her adoptive home and was living in an abandoned house in North Bellport when she was questioned by police about the Watson murder. By the time of the trial, she had become pregnant and felt very vulnerable.

“I felt badly about providing false testimony, but I was afraid of the police and prosecutor,” said Bell in a 2016 affidavit supporting Bush. “I believed that I had no choice but to go along with what they wanted me to say.”

Bell’s affidavit suggests she was coached by Suffolk authorities. “I think that I must have told the police what they told me to say,” Bell now says. “I believed I was doing the right thing by confirming what they already believed.”

To be sure, there were earlier indications that Bell might not be telling the truth. At the 1976 trial, Bush’s defense lawyer Harold Seligman called other witnesses who said they never saw Bell at the house party prior to the murder.

‘I told the judge and the prosecutor that I lied at Keith Bush’s trial … I thought the judge would believe me when I told the truth.’ -Maxine Bell, prosecution’s key witness in 1976 trial who later recanted

Nevertheless, Bell’s change in her story came as a big surprise at the 1980 hearing about the legal admissibility of Bush’s confession. By then, Bell had moved to Alabama and gotten married. Suffolk prosecutors paid for Bell’s plane ticket to return to Long Island so she could reprise her trial testimony against Bush.

Instead, during the 1980 hearing, Bell balked.

“I refused to repeat my false testimony,” Bell explained. “I told the judge and the prosecutor that I lied at Keith Bush’s trial. No one pressured me to admit to my lie or to finally tell the truth. I thought the judge would believe me when I told the truth.”

But in an April 1981 decision, Tanenbaum said he didn’t believe Bell’s recantation. The judge determined enough other evidence existed to uphold the “probable cause” legality of the police interrogation of Bush.

Although Bell’s “crucial testimony” was believed by the 1976 jury that convicted Bush, Tanenbaum now ruled, her new hearing testimony suggesting Bush’s innocence “was not believable.”

Tanenbaum noted that Bell had received “some psychiatric care,” attempting “to commit suicide with the use of Excedrin,” according to court records, apparently referring to the over-the-counter pain reliever.

The judge also pointed out that Bell had reaffirmed to Suffolk authorities her incriminating account against Bush up until one week before the November 1980 hearing when she recanted.

“Now married and a homemaker, she has matured into a disturbed adult who was clearly not a credible witness,” Tanenbaum concluded about Bell’s recantation.

In addition, the judge underlined other evidence sufficient enough for police questioning — such as the metal comb linked to Bush that allegedly caused Watson’s wounds and a statement by Watson’s friend Brenda Carlos who told police that Sherese said Bush “would walk her home” after the party.

Based on this other evidence, Tanenbaum ruled, it was “reasonable to conclude that the police had probable cause to arrest the defendant.” His decision was later affirmed by the Appellate Division.

With this denial, Bush would have to wait another 20 years for his next best legal chance of being proved innocent.

In retrospect, Bell told Newsday she was stunned that Tanenbaum didn’t throw out Bush’s murder conviction when she admitted she lied about being at the 1975 party.

“I went before the judge and thought it would change everything but it didn’t,” said Bell, who now uses her married surname of Weber. “Everybody knows I wasn’t there” at the party.

For years after, Bell says, she suffered pangs of conscience about her false testimony. She was desperate for forgiveness, she says, from the former schoolmate whose life she had helped ruin.

In November 1992, Bush received a handwritten letter from Bell, apologizing for all she had done. She expressed deep regrets and said her life had been “a living hell” because of guilt about her actions.

“I am very sorry for what’s happin [sic],” Bell wrote him. “I took your life from you and I can’t put it back. I no [sic] that you are INNOCENT.”

The DNA tests

In December 2000, Suffolk’s then-District Attorney James M. Catterson Jr. announced that his office would be the first in New York State to review DNA evidence routinely in cases brought by prisoners who said they were wrongly convicted.

“There are so many defendants sitting in jail that have been claiming innocence and who do not take advantage of it [DNA analysis] one way or other,” Catterson told The New York Times, “and I could sit back and wait for them to make their motions, but here’s a process where once and for all we can clear up the backlog.”

Such genetic technology — a powerful tool in proving guilt or innocence — wasn’t available when Bush was convicted in 1976. But by 2000, the telltale clues of DNA markers — found in the blood, hair, fleshy tissue, bones and bodily fluids taken from a crime scene — began to be embraced by prosecutors and defense lawyers alike around the country.

When he first heard of Suffolk’s DNA fingerprinting, Bush had been imprisoned for more than a quarter century. His cause seemed hopeless. It looked like he had run out of options to prove his innocence.

‘I practically begged them for three or four years, like ‘Listen I want you to take my DNA and test it against any physical evidence you got’’ -Keith Bush

In 1989, Bush had filed a Freedom of Information request, asking for “any and all detective reports concerning this case.” Suffolk officials approved the request but made no mention of John W. Jones Jr., the other potential suspect in the case. Bush also filed a federal habeas corpus appeal in the 1990s without success.

Bush had pleaded for executive clemency from the governor, but that too was turned down. “Pardons are generally considered only when there is overwhelming and convincing proof of innocence which was not available at the time of conviction,” wrote the director of the Executive Clemency Bureau.

When he heard about Catterson’s DNA initiative in the early 2000s, Bush quickly responded. The DA’s office offered only a glimmer of hope.

“Obviously, the only cases that can be reviewed are those in which DNA material was gathered at the crime scene and is presently in existence, and where all reasonable people agree that an exclusion would mean an exoneration of the convicted individual,” wrote back a Suffolk assistant district attorney in September 2001.

Insisting on his innocence, Bush offered to provide any blood or human tissue samples of his own. He was confident none of his DNA would be found at the murder scene.

But his wait would take several years until the crime lab determined that there was DNA evidence found and preserved from the Watson murder scene and compared it with the Bush samples.

“I practically begged them for three or four years, like ‘Listen I want you to take my DNA and test it against any physical evidence you got’,” recalled Bush.

Finally, Bush got the big break he was hoping for. In 2006, Suffolk authorities found and tested DNA evidence recovered from the Watson murder scene. They discovered human tissue from an unknown male underneath Watson’s fingernails.

The crime scene DNA was compared with a swab of body fluids taken from Bush. None of Bush’s DNA matched the male DNA found on Watson’s body.

This new scientific findings, using high-tech detective skills, ruled Bush out as Watson’s murderer, his lawyers said.

“The test results are compelling proof that Mr. Bush did not kill” Watson, argued his appeals lawyer Adele Bernhard. “Someone else struggled with the victim. Someone else’s skin cells lodged under her nails in that struggle.”

The use of DNA in the Bush case convinced Bernhard, a law professor, to take on his appeal. First at Pace University’s law school and then later at New York Law School in Manhattan, Bernhard worked with her students to review available evidence in Bush’s long-running case, which led her to believe he had been wrongly convicted.

“My clinic is designed to try and sort through all the requests for assistance that we get and try and look for people who we think may be innocent,” Bernhard explained. “I think Keith Bush is innocent because all the evidence points to his innocence.”

In reviewing Bush’s case, Bernhard also learned of Suffolk’s controversial past in handling murder cases, including the 1989 state investigative report criticizing several questionable practices by Suffolk police and prosecutors including Rafferty, the key investigator in Bush’s case. Bernhard said the Bush homicide case contained many similarities, including allegations of coerced confessions, threats of violence, and poor evidence-gathering by police.

Rafferty and other detectives “who produced Mr. Bush’s confession,” Bernhard noted, “were later found to have used violent ‘third degree’ tactics to obtain confessions in other cases.” Citing the 1989 state commission report, she said “Mr. Bush described the Suffolk County detectives’ illegal interrogation techniques before these same techniques were proven, by official investigation, to have been used in other homicide cases.”

The problem of evidence-gathering became evident in 2006, when the Suffolk District Attorney’s office agreed to a DNA test on the metal comb, the same one that authorities said Bush used to attack Watson. Bernhard felt that perhaps a DNA test on this metal comb would yield more clues, particularly about the unknown male whose DNA was found underneath Watson’s fingernails.

But Bernhard learned this key piece of evidence — an alleged murder weapon — was now missing. According to Suffolk Police Property Bureau records, the metal comb with a wooden handle had been inexplicably destroyed in 1983 and thus couldn’t be tested for DNA.

After reviewing photos of the girl’s body, Bernhard concluded this police claim about Bush and a metal comb didn’t make sense overall. “They took a comb from his house and entered that into evidence and argued to the jury that this was the very weapon that caused these wounds,” Bernard recalled. “When you look at those wounds and compare it to that weapon, there is no way that that weapon could have caused those wounds.”

Nevertheless, Bernhard felt she had enough to go forward. Bernhard asked a Suffolk court to throw out Bush’s conviction. She cited the unknown male DNA evidence found underneath Watson’s fingernails and the 1989 state investigative report. This process would take another two years.

During this appeal, Bernhard faced strong resistance from then Suffolk District Attorney Thomas Spota, who had defeated incumbent Catterson in 2001 with the help of Suffolk’s powerful police unions. She felt frustrated by legal wrangling that dragged on for months while Bush remained in a prison cell.

In retrospect, Bernhard now says, Spota should have considered recusing himself from any involvement in the Bush appeal to avoid any appearance of a conflict of interest. After they left the DA’s office, where they had worked together, Gerard Sullivan — who prosecuted the Bush case — and Spota became private law partners in the early 1980s. And Spota had also been the lawyer for the Suffolk Detectives Association, which represented those involved in the Bush case.

“Maybe he should have because he was connected to the important parties in the case, and would have had an interest in seeing the case not overturned,” said Bernhard, who explained she was unaware of these possible conflicts until recently.

In an interview, Spota said he knew nothing about the Bush case, including any issues such as a possible conflict of interest or requests about genetic testing from the Watson murder scene. A decade ago, Spota said, his DA office handled thousands of criminal cases and he couldn’t recall ever discussing anything about the Bush matter. “I didn’t know anything about the request for DNA,” Spota said. “I knew nothing about it, no knowledge.”

Spota said he and Sullivan parted as law partners under less than amicable circumstances in the 1980s, but he defended his deceased former friend and colleague as a skilled and ethical prosecutor. “I never knew him to do anything wrong,” said Spota, when asked why Sullivan never revealed the other potential suspect during Bush’s trial. “Nothing like this.”

Nevertheless, if Bush hoped that DNA would clear his name, he was soon disappointed.

In court papers, Spota’s office vigorously contested the DNA results. It raised the possibility the human tissue samples scraped from Watson’s fingernails could have been inadvertently “contaminated” during the police recovery of evidence. And it argued that other questions about Bush’s guilt had been settled long ago.

“The DNA evidence he [Bush] has presented does not exculpate him and he cannot use it as a means to embark on a fishing expedition,” contended Suffolk Assistant District Attorney Rosalind C. Gray in June 2008. “The DNA profile, which resided in the scrapings for 30 years, could have been there before the murder; there is no way of knowing.”

Gray, who is still with the Suffolk District Attorney’s office, was not available for comment for this story, according to a DA spokesman. Those familiar with the DA’s ongoing review say that while Gray had full access to the Bush case files for several years, there is no evidence that Gray knew of Jones’ incriminating police statement or the lie-detector report.

Though Rafferty testified at trial that Bush grabbed Watson by the throat and stabbed her repeatedly with a metal comb, the Suffolk DA now argued that there was no evidence that Watson had injured her attacker and that Bush showed no sign of injury at the time of his arrest.

In a 2008 decision upholding the conviction, acting County Court Judge Martin I. Efman agreed with the Suffolk DA and expressed doubt that DNA testing would have made a difference in the jury’s guilty verdict. Efman said fibers linked to Bush’s coat and found underneath Watson’s fingernails still provided sufficient evidence of his guilt.

“Defendant’s use of the DNA test results as a springboard for the argument that, had such evidence been received at trial, the verdict would have been more favorable to the defendant is highly speculative and conclusory,” Efman ruled.

And even though Suffolk authorities had been criticized for their methods in a 1989 state investigative report, Efman ruled that Bush “produced no evidence that law enforcement acted improperly in his case.”

However, the DA’s office never informed the judge of all the evidence prosecutors possessed.

In an interview, Efman said he had no knowledge of Jones, nor of his incriminating police statement and lie-detector report in the DA’s files.

Efman, who recently retired from the bench, said any exculpatory evidence should have been made known under legal precedents commonly called the “Brady” rules. The landmark 1963 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Brady v. Maryland, requires prosecutors to turned over any exculpatory evidence that would likely exonerate a defendant.

“Any Brady material should be brought to the attention of the defense and the judge if it exists,” said Efman.

Once again in 2008, Bush’s legal efforts had failed. His conviction as a murderer and sex offender would remain intact.

But Bush no longer feared he’d spend the rest of his life in a cell. Around this time, to his great surprise, Bush was released from prison.

Paroling the sex offender

For more than a dozen years, Bush had been willing to stay behind bars rather than admit to murdering Sherese Watson. He refused to do so, even if such an admission meant he could become a free man.

Starting in 1994, Bush became eligible for parole, based on the 20-to-life sentence given to him by Judge Tanenbaum in 1976. Every two years, a parole board would review Bush’s case and decide whether he was a candidate for release.

But an important part of this process involved whether Bush, like others eligible for parole, would express remorse and responsibility for the crime.

“I ran across another crossroad because I wasn’t just going to admit to this crime under no circumstances,” Bush recalled. “And Parole made it clear that they weren’t going to consider my release without it.”

While records show parole boards generally do consider an inmate’s remorse and other factors, incarcerated individuals are not required to admit their guilt to be considered for parole, said Thomas Mailey, a spokesman for the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision.

However, hearing transcripts show Bush’s parole board insisted early on that he admit “culpability” for Watson’s death.

“You denied your culpability,” the board told Bush, in rejecting his 1996 bid, saying he “expressed limited insight and understanding as to your violent bizarre conduct.”

Bush found himself caught in what he considered an awful Catch-22. He could either admit to a sex-related murder that he said he didn’t commit and undergo sex-offender counseling, or he wouldn’t get out of prison. An exchange during his 1998 hearing at the Fishkill Correctional Facility illustrated Bush’s dilemma:

“Why did you commit this crime?” a commissioner asked him.

“I didn’t commit the crime,” Bush replied.

“What is your theory as to how this young lady died?” the commissioner demanded.

As he would at other hearings, Bush went into a long explanation of his actions on the night of the murder, emphasizing he had nothing to do with Watson’s death. And at this hearing, as at others, the board members let Bush know that they were not interested in relitigating his case.

Guilt or innocence was an issue already decided by a jury and appeals courts, they told him. Instead, the parole board looked for an admission from Bush before they would consider releasing him.

“So, one of the requirements is that I would have to admit to guilt?” Bush asked the parole panel at this 1998 hearing.

“That is the first step in the rehabilitative process,” one of the two commissioners replied. “The very nature of rehab implies that the offender internalizes culpability, and then makes a commitment to address the behavior. You don’t seem to have gotten there in 24 years.”

“Does that mean that I will never get out of prison?” Bush asked.

“I’m not saying that,” the commissioner replied. “I am saying that you have not approached the threshold of that process. What else have you accomplished in the last 24 years?”

Bush pointed to his college associate degree earned while in prison. His family also had arranged for a job awaiting him if he got out. But at this hearing, Bush couldn’t hide his terror.

“I am lost, I am lost,” he explained. “I don’t want to die here, man. You know, for 24 years I have been trying to prove my innocence.”

The board was unmoved. “You lost your presumption of innocence when you got convicted,” a panel member told him. “We have to treat you as though you committed this crime. This is a very gruesome crime, Mr. Bush.”

After being denied six times, Bush was eventually granted parole and released in March 2007. The surprise decision came about without warning during the debate about the DNA evidence in the Watson murder and Bernhard’s involvement on his behalf. Bush says it happened without having to admit to a crime he didn’t commit.

His principled stand impressed those who knew him. “Everytime he came up for parole — and he came up for parole every two or three years — he refused to admit,” recalled Seligman, his trial defense lawyer. “I’m sure it was proposed to him ‘if you just admit it, they’ll let you go home’. So he spent another 10 to 15 years in jail that he didn’t have to, because he couldn’t just admit that he did this.”

After 32 years of incarceration, Bush walked out of the gates of Wende Correctional Facility near Buffalo.

Outside, his brother and sister-in-law were waiting to drive him home. “There was a sense of joy, a sense of freedom for that release,” Bush recalled, “yet I knew there was still a lot of things I had to do in terms of trying to exonerate myself.”

In an interview, Bush says his darkest, most desperate years were those after he had exhausted his formal legal appeals. He had to become his own jailhouse lawyer, filing Freedom of Information requests and pro se — on his own behalf — legal appeals.

During this period, Bush’s family and friends helped him checking out clues and seeking new evidence to prove his claim of innocence. All during that time, he felt his life slipping away in what seemed a futile shuffle of court papers.

“You’re talking about decades,” recalled Bush. “You’re talking about that transition from boyhood into manhood inside of a cage.”

Under the terms of his lifetime parole, Bush would be listed as a Level 3 sex offender, the most serious kind. Because of his conviction on attempted sexual abuse in 1976, his face still appears today on the internet, warning that he is a “sexually violent offender.”

No longer a Long Islander, Bush lives in a Connecticut house owned by his mother. Yet, in a sense, he still doesn’t have his freedom. He must stay in regular contact with parole officers from both states.

“I had to basically register as a sex offender,” he explains. These restrictions included a general ban on going near anyone under 18. “So that type of pressure played a significant role in my transition from prison life to community life.”

Shortly after his release, Bush was reminded of the indignities of being labeled a sex predator when he and some of his family were urgently called to a fire at a Bridgeport house where Bush’s niece, her husband and their five children lived.

As they watched the blaze engulf the home, his family advised Bush to stay away from the children, lest he get into trouble with his parole board.

But Bush did get in trouble in 2014 when he attempted to write his memoir on a computer. For Bush, writing about his experiences as a self-professed “innocent man” was like a form of therapy, of trying to make sense of a chain-reaction of events that had forever changed his life.

After more than four decades, his constant appeals and court filings had become like “Bleak House,” the famous Charles Dickens novel of the never-ending legal case.

“I really wanted to tell the story because I felt if I don’t get exonerated, then this will be my form of revealing the truth,” Bush explained. “And the book will be a form of exoneration for me.”

But under his restrictions, Bush wasn’t allowed to use a computer with internet access without paying a monthly fee so the state could monitor his activities. During an inspection of his home, parole officials became aware of Bush using a computer owned by his niece to write his memoir. Bush said he didn’t go online, but his failure to pay the $30 monthly computer fee resulted in a parole violation.

As a person convicted of sex-related murder, there was no room for excuses. Bush was ordered to spend another year in jail in New York.

When he got out and returned to Connecticut, Bush once again tried to re-establish a normal life. He now works full-time as a forklift operator in Bridgeport, and has a steady girlfriend.

But Bush’s legal status as a convicted murderer and sex offender still hangs over his head, a status he’s determined to rectify. Getting exonerated from Watson’s murder would also mean his sex offender status will go away.

The mystery man revealed

As Bernhard and her law students researched Bush’s case, there was an increasing mystery surrounding two very different combs — one metal, the other black plastic — each with crucial meaning to the Watson murder investigation.

During the 1976 trial, Suffolk authorities insisted that Bush had used a metal comb with a wood handle to jab Watson in the back while he choked her to death. A metal comb, which Bush said was another relative’s, was confiscated from his home at the time of his arrest. Bush insisted he didn’t have any comb on the night of the murder because his Afro-style hair was in braids.

But whatever DNA evidence the metal comb may have contained was lost when the police destroyed the comb in 1983.

As Bernhard’s law students reviewed the case, however, increasing attention was paid to the other comb in the Watson murder — the long black plastic comb found beside her body in 1975.

During Bush’s trial, the black plastic comb seemed peripheral, particularly since Suffolk police and prosecutors emphasized the metal comb as an instrument of Bush’s attack on Watson.

A scan of the metal “Afro” comb police said they recovered from Bush’s Bellport home. The comb itself was destroyed in 1983. Credit: Suffolk County Medical Examiner’s Office

A black, plastic comb found at the 1975 Sherese Watson murder scene in North Bellport. This comb was later identified by John W. Jones Jr. as his own. Photo credit: Government Exhibit

Nobody at the trial seemed to know who owned the black plastic comb, defense lawyer Seligman recalled. And Sullivan and Rafferty never revealed that John W. Jones Jr., the other possible murder suspect, had identified the black plastic comb as the one he lost when he tripped over Watson’s body on the night of the murder, according to the written statement Jones gave police.

But the black plastic comb steadily took on new importance during the DNA analysis in the mid-2000s, when a court judge allowed much of the physical evidence to be reviewed for possible traces of telltale genetic clues.

In December 2008, Arthur W. Young, a forensic biologist working with Bernhard, visited the Suffolk Crime Lab. Accompanied by Suffolk ADA Rosalind Gray and others, Young examined and photographed all of the available evidence taken from the Watson murder scene.

One particular piece of evidence stuck out among the rest — the black plastic comb.

“The afro pick was packaged in an unsigned/unsealed clear plastic bag,” Young described in a memo to Bernhard, next to a police photo of the black plastic comb. “Documents indicate that it was recovered near the victim’s body. According to ADA Rosalind Gray, this item was in the DA’s file and not stored with the remainder of the evidence.”

Though it seemed odd for the black plastic comb not to be with the rest of the murder evidence, Bernhard and her students didn’t make much of it at first.

They were unaware that Jones had claimed it as his own years earlier. And if DA Spota’s office knew the back story of the black comb, it wasn’t revealed to Bush’s lawyers.

Newsday’s review of court documents over the history of the Bush case shows that other Suffolk prosecutors — in addition to trial prosecutor Sullivan — had access to the DA’s office files, but it’s not clear why the evidence containing the Jones police statement and his lie-detector results was never disclosed.

Bernhard shakes her head about why this information about a second suspect never came out.

“We are talking about people’s lives, bottom line,” Bernhard said about the Suffolk DA’s actions in handling this case and its appeals a decade ago. “You’ve got a file. You’ve got information, you should be looking at it and then you should be making a decision. If they looked at it, even in 2008, they certainly should have disclosed it then.”

Bernhard also wondered why the existence of the black plastic comb didn’t come out during the murder trial.

“For reasons not clear from the record, the prosecution did not introduce into evidence the plastic afro-style pick comb found at the scene,” she wrote to the judge in 2008. At this point, Bernhard still had no idea of the black comb’s link to Jones.

Indeed, Bernhard’s effort to clear her client’s name seemed at a standstill, especially after Suffolk Judge Efman turned down her request to vacate Bush’s conviction. However, the judge did allow some further DNA testing, raising even more questions in the years to come.

Another genetic test in 2009, this time on the black plastic comb, also revealed male DNA from someone other than Bush. But just like the DNA found underneath Watson’s three fingernails in 2006, it wasn’t clear to whom this male DNA might belong.

Then in 2011, a New York appellate court allowed further DNA testing on Watson’s other fingernails. But again, no meaningful evidence could be obtained.

Determined to find out everything about Bush’s case, Bernhard and her students filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Suffolk police.

At first, Suffolk denied this record request. But when Bernhard persisted with a lawsuit, Suffolk officials relented.

Soon the significance of the black plastic comb would become much clearer.

In October 2017, the Suffolk police department disclosed to Bernhard a group of crime reports and photographs about the Bush case — including two never seen before by defense lawyers.

The first was a July 1975 detective’s report filed by Rafferty. It described transporting an individual — later identified as Jones — to Manhattan so polygraph expert “Richard Arthur [sic]” could conduct a lie-detector test.

In his report, Rafferty repeated the polygrapher’s judgment that the suspect “was telling the truth.” Rafferty ended his report with “Investigation continuing.”

However, the redacted version of Rafferty’s report given to Bernhard in 2017 crossed out Jones’ name and street address in black ink. The identity of John W. Jones Jr. — whose name was scratched out — would still remain a secret to her.

Nevertheless, it became clear that Bush — already in the Riverhead jail at the time of this 1975 lie-detector test in Manhattan — wasn’t this mystery man.

Bernhard realized none of the information about Jones had ever been disclosed, certainly not during Bush’s 1976 trial, as would be expected under so-called “Brady” court rules.

The second document released by Suffolk police in October 2017 provided another tantalizing but open-ended clue.

This document — a Police Identification Section report written shortly after Bush’s January 1975 arrest — showed Bush’s fingerprints were compared to the “latent impressions on file with this case,” and that there was no match. “No identity was found to exist,” the report concluded. However, in ruling out Bush, this fingerprint report didn’t mention from which piece of evidence the “latent” fingerprint was taken.

For a time, Bernhard wondered if this unknown piece of evidence might be from the black plastic comb, but it eventually proved not to be the case.

In March this year, Assistant District Attorney Howard S. Master, who heads the county’s Conviction Integrity Bureau, told Newsday that the “latent fingerprint” came from a red car mentioned in testimony at the trial, not from the black plastic comb, and that it did not belong to Jones. No longer did this second document seem to hold as much significance as once believed.

Still, more clues followed. The biggest breakthrough occurred in May 2018 when current Suffolk District Attorney Timothy Sini’s office disclosed additional documents, this time identifying John W. Jones Jr. as the mystery suspect.

First, the DA turned over the polygraph report with Jones’s name on it, the one sent to prosecutor Sullivan in July 1975. It also released the actual handwritten Jones police statement taken by Rafferty with other Suffolk detectives in May 1975, a few months after Watson’s murder.

The details were startling. In his signed statement, Jones admitted to leaving drunk from the North Bellport party around the time Watson was killed, tripping over her body in a weeded field, and dropping his comb when he stumbled. And in examining the photo of the murder scene, Jones acknowledged that the black plastic comb “looks just like the one” he left behind.