What’s going on with the Russian estate on Long Island?

A nearly century-old mansion on Long Island’s North Shore is still the focus of a diplomatic dispute between the United States and Russia that has lingered from shortly before President Donald Trump took office.

The United States barred Russian diplomats from the Nassau estate in retaliation for Russia’s alleged interference in the U.S. presidential election and harassment of U.S. diplomats in Russia, charges that the Russian government has denied.

However, for some Long Islanders this throwback to the Cold War is more about lost dogs, holidays gifts and armed guards than international intrigue.

How did we get here?

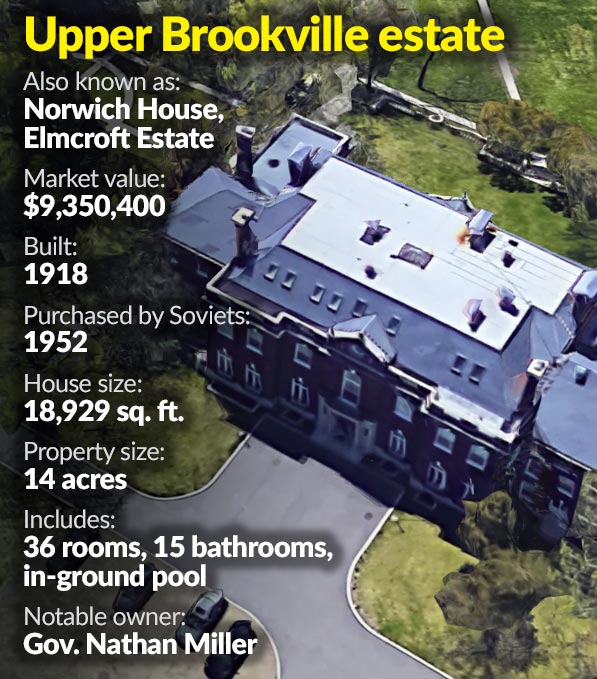

The 18,929-square-foot Russian-owned mansion and 14-acre property on Mill River Road in Upper Brookville, described by the U.S. government as a “recreational compound,” was ordered closed by President Barack Obama’s administration on Dec. 29, 2016. The next day, 35 diplomats were expelled from the premises.

(Credit: Google Maps)

Russia has repeatedly condemned the compound’s closure, charging that it is a violation of international diplomatic agreements. And Cold War experts have said they could not recall another example of a decision to bar diplomats from entering Soviet- or Russian-owned property, according to a McClatchy report.

Russian officials on July 28 ordered the closure of a U.S. recreational retreat and warehouse in Russia, a move described in news reports as in part retaliatory. Russia also ordered the United States to cut its embassy and consular staff in Russia by 755, in retaliation for Congress approving new U.S. sanctions against Russia, which Trump signed into law days later.

Upper Brookville estate closure timeline

Dec. 30, 2016

Dec. 30, 2016

Russian diplomats vacate the compound on Mill River Road in Upper Brookville after it was ordered closed by President Barack Obama.

Credit: Howard Schnapp

July 7-8, 2017

July 7-8, 2017

President Donald Trump and Russian leader Vladimir Putin discuss the mansion at the G-20 summit in Hamburg, Germany. Credit: AP

July 28, 2017

July 28, 2017

Putin orders the United States to cut its diplomatic staff in Russia by 755 in retaliation for Congress approving new sanctions. Credit: AP

Aug. 2, 2017

Aug. 2, 2017

Trump signs the bipartisan Russia sanctions bill, but calls it “seriously flawed,” drawing the ire of Democrats, including Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer. Credit: AP

Seemingly decent but distant neighbors

Liz Berens, 69, of Upper Brookville, has closer ties to the mansion than a typical Long Islander. She is the granddaughter of former New York Gov. Nathan Miller, the estate’s previous owner. In 1952, Miller sold the property to the Russians, according to Newsday reporting.

The house, also known as the Elmcroft Estate and Norwich House, had become “very proletarian,” she said, comparing it to her memories of visiting the property as a child, and her last visit from about 15 years ago.

“All of the beautiful details were gone. It was very sparse,” Berens said.

Shortly after her last visit, she said the FBI interviewed her and showed her a blueprint of the house, asking her to note each room she saw and to describe it. An FBI spokeswoman said the bureau had no comment.

Berens said the Russians were “decent neighbors,” but when the closure was announced, she “wasn’t surprised that there were perhaps intelligence operations going on there.”

Norwich House seen in an undated photo. (Credit: Courtesy of Liz Berens)

Dan Travers, 56, who has lived across from the compound for more than 12 years, said he never noticed any “unusual activities” on the property.

Travers said his only encounter with someone from the Russian compound came about two years earlier after his dog walked across the street and spent the night against the property’s fence.

“Someone called us who didn’t speak English” and managed to communicate that the dog was there, Travers said.

Alexa Roland, 23, who lives less than a quarter mile from the compound, said that when she was about 10 years old, her mother, out of curiosity, drove up the driveway, which at the time had no gate.

“Two men came out and they were armed,” Roland recalled. “They asked what we were doing and said, ‘We’ll have to search you. This is Russian property.’ ” The men searched the car, Roland and her mother, and then told them to immediately leave, she said.

Nick DeMartino, who said he had lived several houses away for five years, said he used to hear people at the estate firing shotguns at clay pigeons on the weekends.

“We knew they were Russian diplomats,” he said in a Reuters report. “We’d seen them driving around town.”

Penny Hallman, another neighbor, said that in the days before the Russians were removed, a man whom she knew only by the title of “senior counselor” stopped by her home with a holiday gift of vodka and candy.

“I hope they come back,” Hallman told The New York Times. “It’s been a pleasure to have them here.”

How has local government reacted?

Upper Brookville Mayor Elliot Conway said he had contact with the State Department, which has maintained the estate since it was ordered shut, and “they confirmed there’s no change” in its status.

“I think the [Russian] mission is a small pawn in a very large and complicated chess game,” Conway added.

Photos: Russian-owned mansion in Upper Brookville closes

In June, Oyster Bay Town officials started charging beach parking and permit fees for members of the Russian mission to the UN. The fees had been waived for decades as a gesture of goodwill.

But officials say the change has nothing to do with international politics, just fairness. Town Supervisor Joseph Saladino said the practice was unfair to residents who pay for the $60 annual permit. He said anyone who is a resident of the Upper Brookville house could buy the permit.

Do the Russians own anything else on Long Island?

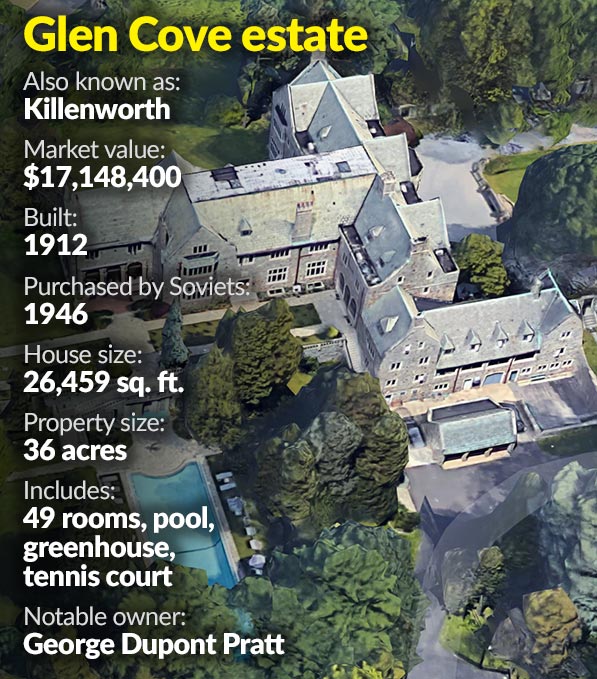

In addition to the Elmcroft Estate, the Soviet Union bought the Killenworth mansion on Dosoris Lane in nearby Glen Cove in 1946, according to a Newsday story from that year. The 26,459-square-foot house was built in 1912 by philanthropist and Standard Oil heir George Dupont Pratt. The property hasn’t been part of sanctions during the diplomatic tiff.

(Credit: Google Maps)

A number of early news reports incorrectly stated the Glen Cove property — not the Upper Brookville mansion — was the Long Island estate that the Obama administration had targeted.

Orin Finkle, 76, of Great Neck, is a historian of Long Island Gold Coast estates. Having acquired many historical photos of such houses, Finkle used his collection to secure a visit to the Glen Cove mansion in 1985.

“I called the UN and said, ‘I know no Americans ever go in that house,’ ” he said. “ ‘I’ll make you a trade: I’ll give you the photos if you let me in.’ ”

The Glen Cove and Upper Brookville properties are outlined in red in the map above. Click on each one for more information.

About one month later, Finkle said he was invited. He walked through, escorted by a United Nations diplomat and two of the Soviets who were staying in the house at the time. They showed him around and discussed the differences between American and Soviet lifestyles.

“It was very pleasant. They were very nice,” he said.

Finkle said they wouldn’t take him upstairs, only showing him the first floor. He recalled “nothing fancy” in the house itself, but said the outside was as “beautiful” as he had seen in older photos.

“Everything looked how it looked back in the old days,” he said. “If I didn’t know that was the Russians, anyone could’ve been living there at the time.”

Photos: Russian-owned estate in Glen Cove through the years

Liam Cox, 19, recalled that when he was a child at a summer camp located on property next to the mansion, counselors would jokingly say, “ ‘Don’t cross over the fence or you’ll get shot.’ ”

The Glen Cove resident said he doesn’t mind the Russian government’s presence in the city.

“I’ve lived here my whole life and it hasn’t bothered me,” he said. “It’s not like anything is going on there.”

Gloria Farino, 87, of Fort Salonga, who was in Glen Cove one afternoon for an eye doctor’s appointment, feels the same way.

“If it has never caused problems before, why would it cause problems now?” she said.

Spying allegations, Khrushchev and Castro

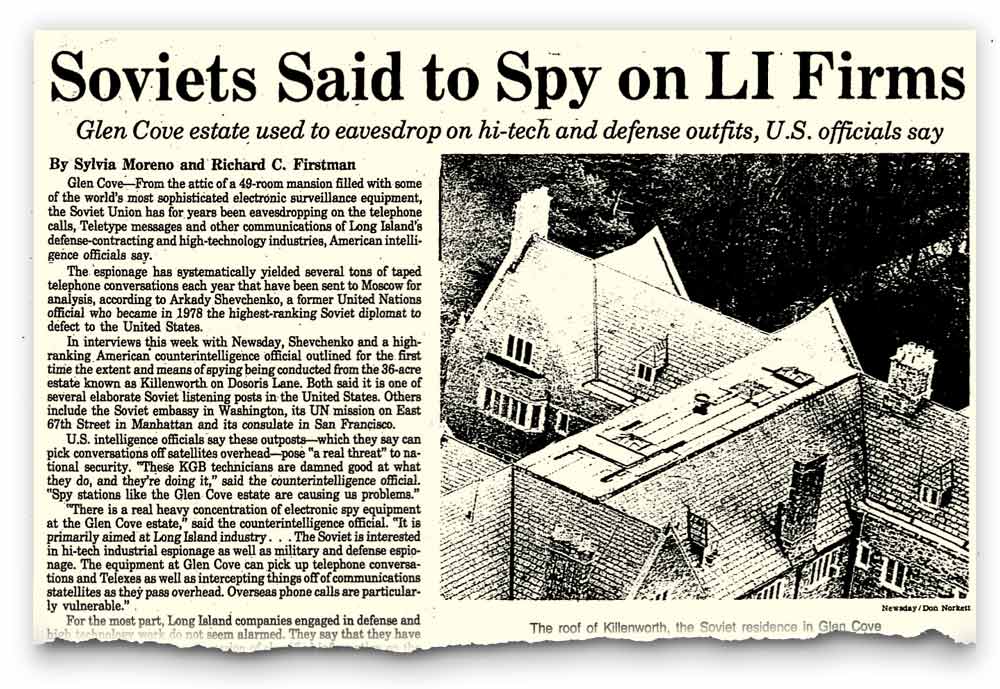

The Soviets installed electronic surveillance equipment at Killenworth to spy on the Long Island defense industry and high-tech firms, a Soviet defector and a U.S. official told Newsday in 1982.

The allegations of spying led Glen Cove Mayor Alan Parente to bar Soviet officials from using city beaches and tennis courts, according to news reports at the time. The Glen Cove City Council lifted the ban in 1984 by a vote of 5-2. The two dissenting voters, Tip Henderson and Ann Gold, said the Soviets should have to pay taxes to use the city’s recreational facilities. They had not done so because the house was under tax-exempt status as a diplomatic consulate.

An April 28, 1982, Newsday article about alleged spy activity conducted at the Glen Cove estate.

Reginald Spinello, the former Glen Cove mayor, recalled that when he was a child in 1960 during a time of tense relations between the Soviet Union and the United States, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev visited the estate.

“People lined the streets,” he said. “They were throwing tomatoes at the limos. People were not happy at the time that he was coming in there.”

The Soviets also once hosted Fidel Castro at the mansion, McClatchy reported.

Could the Trump administration let the Russians back in the Upper Brookville compound?

Only if Congress agrees. The new sanctions, which Trump reluctantly signed into law on Aug. 2 after they overwhelmingly passed the House and the Senate, require congressional review of any administration plan to return the property, news reports say. It’s unclear what will happen to the estate if the Russians are not allowed to return.

Top image credit: News 12 Long Island

Design: Matthew Cassella Map: Tim Healy Illustration: Seth Mates Copy editor: Jennifer Martin Research: Laura Mann, Judy Weinberg Production: Joe Diglio