The Mission. The Module. The Memories.

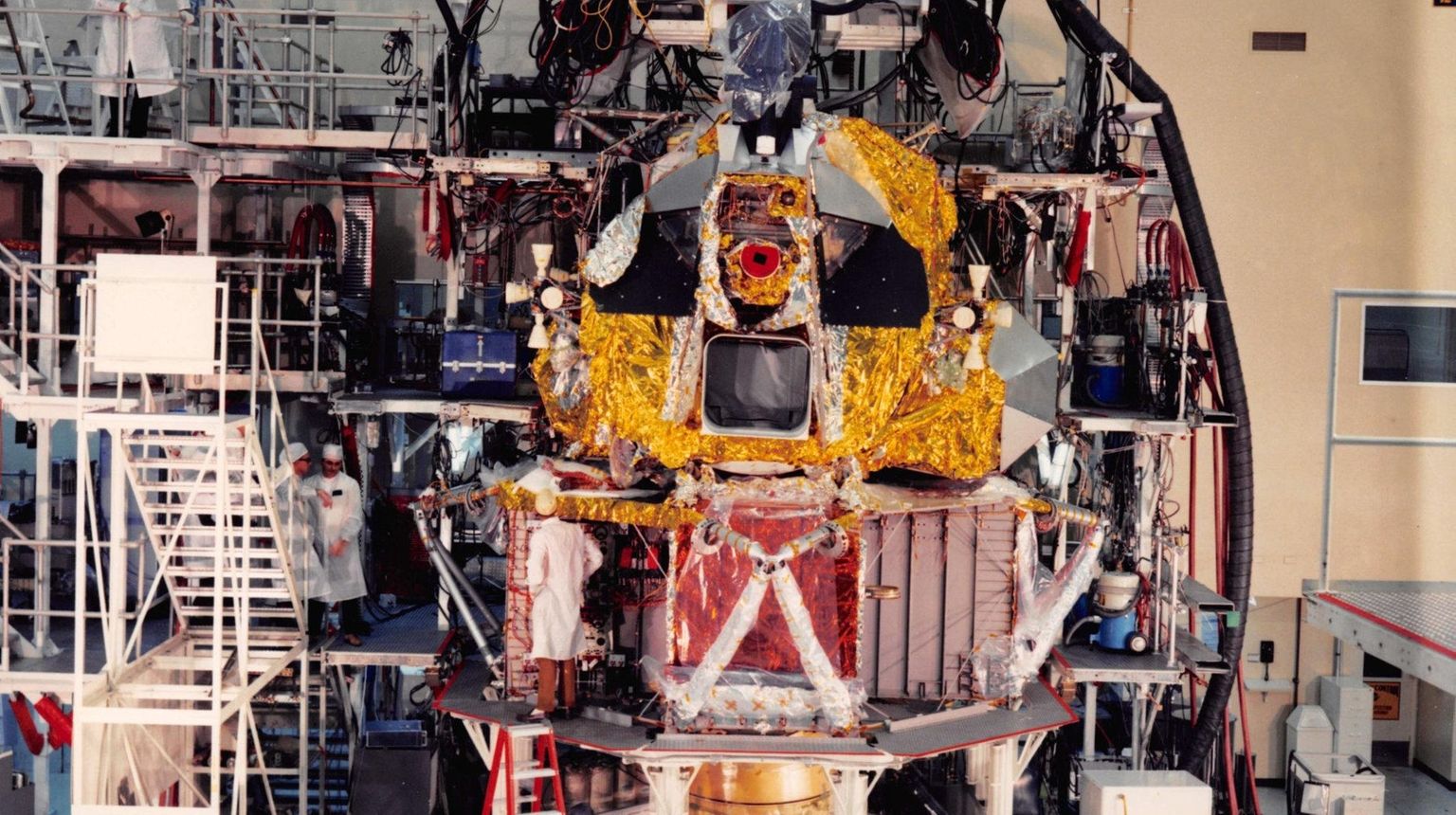

The Apollo 11 flight marked a turning point for America, the realization of a dream a decade in the making. And Long Islanders played a fundamental role in the mission: They were the men and women who fashioned the Eagle, the lunar module that carried Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin from the command module to the moon’s Sea of Tranquility.

On the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing, Newsday celebrates the people who worked tirelessly to propel the lunar module into history.

The beginning

Made in Bethpage: How Grumman got the contract

When Grumman was launched in 1930, there was scant thought of moon shots. Instead, Huntington native Leroy Grumman and his co-founders were scrambling for funds to open an aircraft repair shop in a decrepit garage in Baldwin.

Three decades later, Grumman was among 11 companies invited to submit lunar module proposals. The company focused on a technique called the lunar orbit rendezvous and that’s exactly what won the bid (though for a period, it looked like that’s exactly what would make it lose the bid when NASA decided it would go with an alternate method). In March 1963, a contract was signed for $387.9 million.

Building a first-of-its-kind spacecraft was daunting. Sixty-hour weeks were common as Grumman employees worked on assembling three lunar modules at once.

But they pulled it off, and the company rose to fortune. Leroy Grumman, suffering from diabetes, retired as chairman in 1966, at which time revenue had tripled to $1.1 billion.

Cradle of Aviation Museum

The mission

Mission accomplished: Apollo 11 restored America's sense of self

The flight of Apollo 11 was epic, but it wasn't easy — and it wouldn't have been possible without a bold president with a vision, the commitment of a nation, billions of dollars and thousands of the best minds.

It started off rocky. Sputnik was a sucker punch. Americans saw the Soviet Union morph from World War II ally to Cold War arch nemesis, and the transformation scared them. Space exploration, as they saw it, was simply the backdrop for something much bigger: military dominance.

The dynamic shifted in November 1960, when the country elected Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kennedy to the presidency.

'Kennedy saw that when the Soviets put the Sputnik satellite up in 1957, … that we could not afford to be first on Earth and second in space,' said presidential historian Douglas Brinkley.

Space was a whole new world to explore, and the moon was where America could reclaim glory.

NASA

The people

We came to know them as Grummanites

Roughly 9,000 of Grumman's 25,000 employees — 36 percent — found themselves attached to the lunar module. Long Island came to know them as Grummanites.

The 2,400 engineers — 1,800 who worked on the module and 600 who worked on ground support — worked out of the Long Island headquarters.

Who were they? Al Contessa was an insulation specialist. He still has a Polaroid of himself squeezed inside the Apollo 11 rocket. Ross Bracco was a structural engineer. He helped redesign the door to the module so an astronaut’s spacesuit wouldn’t be in danger of catching.

One thing they all had in common: They were thrilled to be a part of it. 'It was a crazy time, but we got it right,' said former technician Gary Morse.

Debbie Egan-Chin

The timeline

Timeline: The road to the contract

December 1960: Grumman begins a feasibility study of a lunar-orbit rendezvous, one of three proposed techniques for executing a moon mission

November 1961: NASA researcher John C. Houbolt breaks protocol and writes to a top NASA administrator, protesting the exclusion of the lunar orbital rendezvous technique from serious consideration

February 1962: Earth orbit rendezvous is instead designated as the primary mode for a lunar landing

April 1962: NASA reviews the lunar orbit rendezvous technique

June 1962: Director of the Marshall Space Flight Center reverses course and recommends lunar orbit rendezvous; top NASA officials adopt the recommendation

September 1962: Nine companies, including Grumman and Republic, submit proposals

November 1962: NASA selects Grumman

Cradle of Aviation Museum

The technology

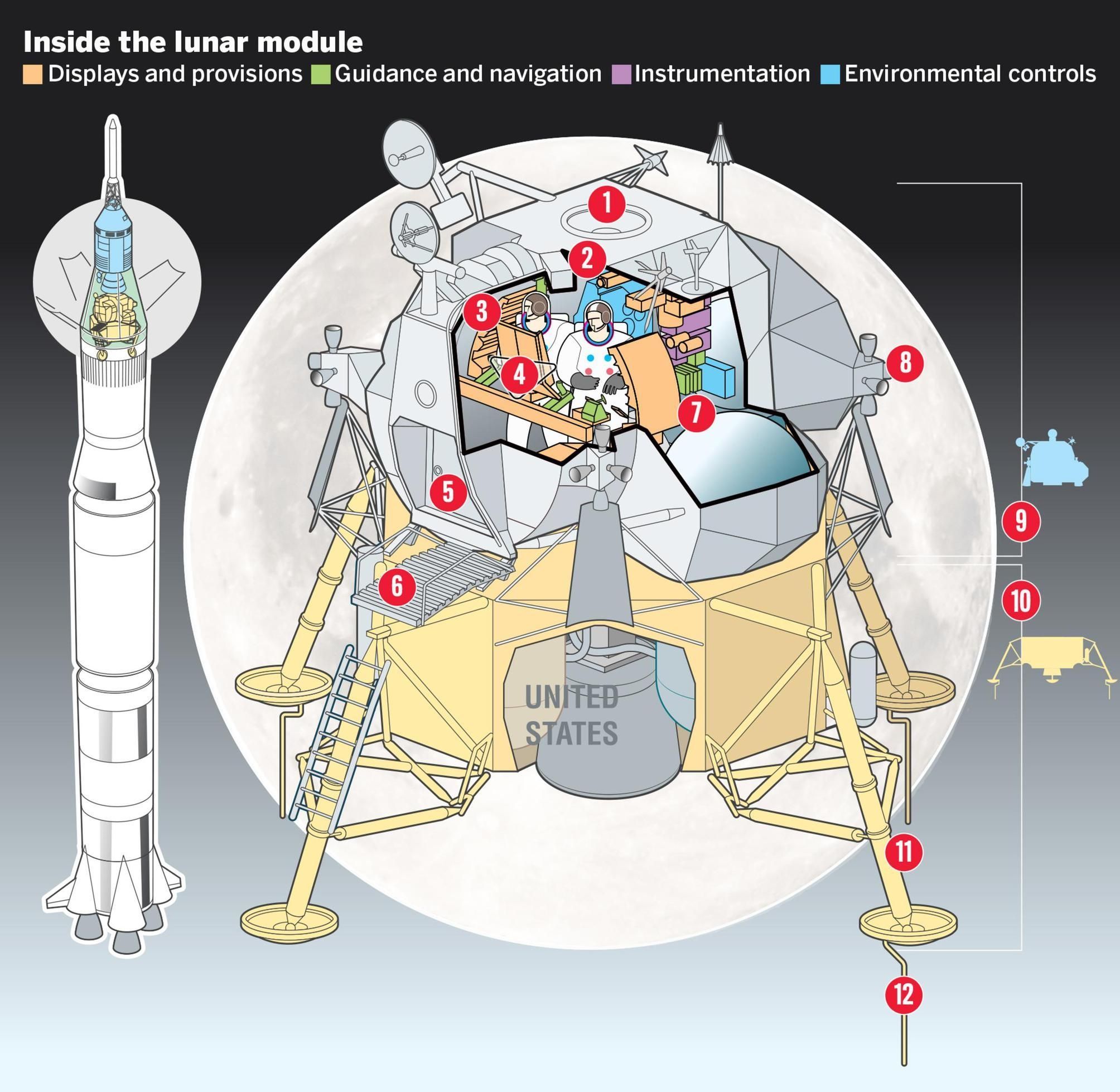

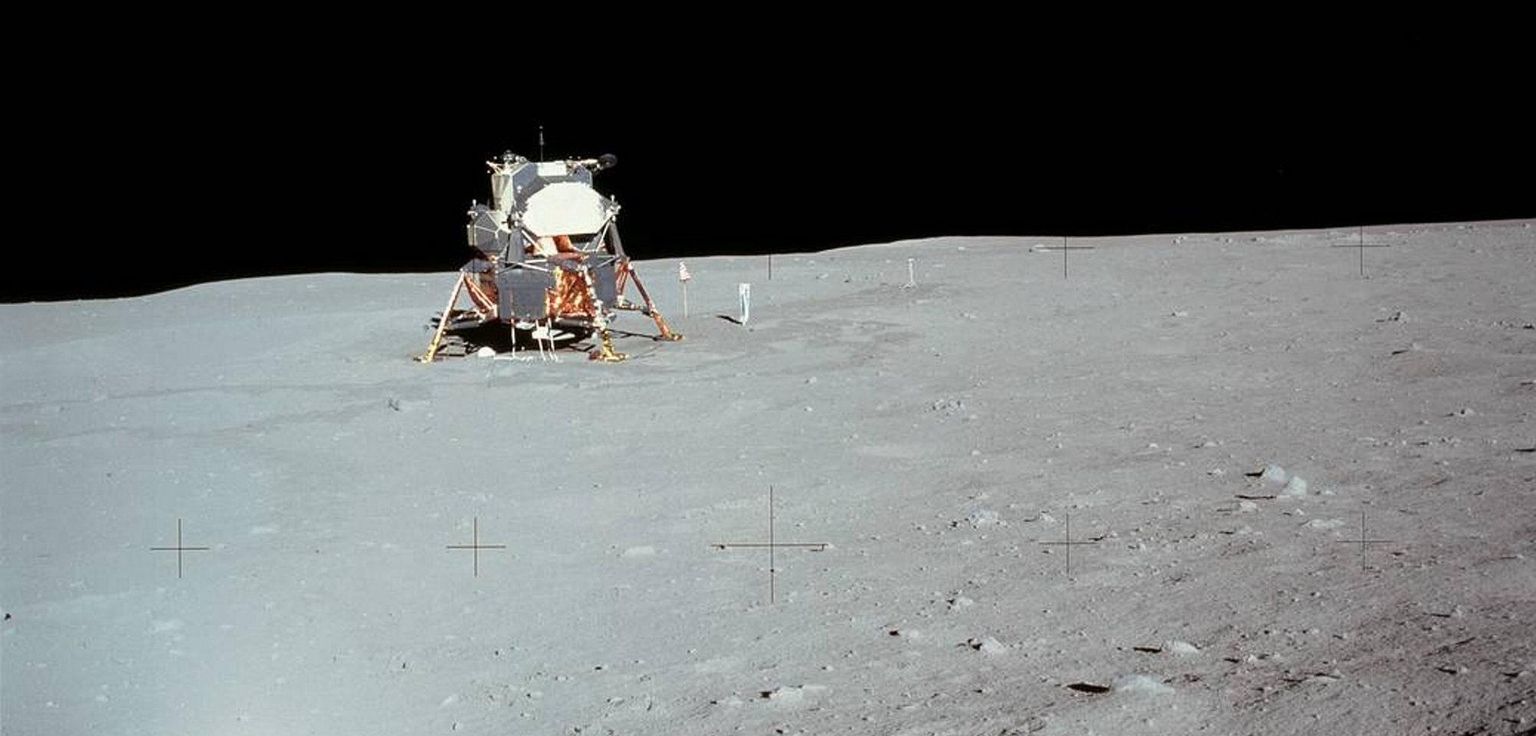

Behind the four-legged robot that walked the moon

No spacecraft capable of transporting humans has been like the lunar module, which possessed legs and feet instead of wheels, had zero aerodynamic design, and was composed of a structural “skin” so fragile that it could have been punctured with a pen.

On first blush, it looked like a four-legged robot that curious aliens might beam down to Earth. Instead, it was the first vessel to make a landing approach by transmitting beams of microwaves to the lunar surface as curious humans descended on an alien orb.

The inventiveness and engineering underlying the development of the Apollo 11 lunar module — and the vehicles that aided its journey — rank among the astounding feats of American scientific ingenuity, experts today say.

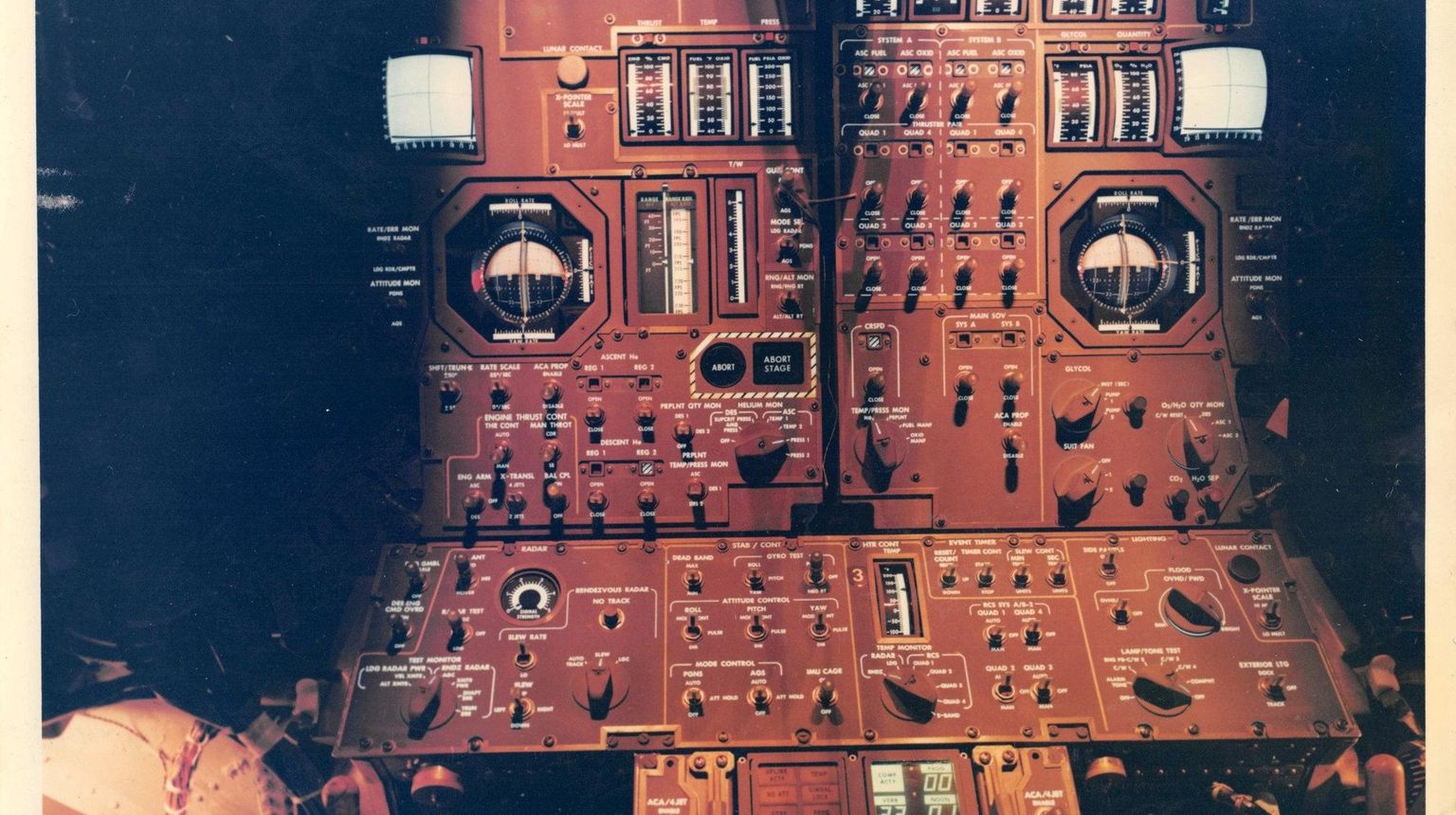

Designers decided the most efficient configuration for the lander would be as a two-stage vehicle — descent and ascent stages — that could function as a single unit during touchdown. The upper section contained the crew’s compartment, control panel, oxygen tanks, radar antennae and fuel – stacked in the rocket.

The lunar module was enclosed in the middle, docked to the command service module, which was at the rocket’s tip and where all three Apollo astronauts rode out of Earth's atmosphere.

The lunar module had to withstand temperatures from 250 degrees Fahrenheit to minus 250. And finally, it had to be light. Ultralight. So the skin of the craft was the thickness of a soda can.

Cradle of Aviation Museum

The technology

Guide to the Eagle

The lunar module was nearly 23 feet tall and 31 feet across. Each metal component was specially milled to remove all but the structurally critical parts. Since there is no air in space or on the moon, there was no need for aerodynamic streamlining.

1) Docking hatch Used to move between service and lunar modules when docked.

2) Hull The wall of the crew cabin was only as thick as three sheets of aluminum foil.

3) Cabin There were no chairs. The astronauts flew and worked standing up, with helmets stowed at their feet.

4) Windows The astronauts had two small, triangular windows to observe the surface while looking for a landing site.

5) Forward hatch Used to get out to the moon surface. Was originally built round, but astronauts said it was difficult to get through in their specialized suits.

6) Egress platform Commonly known as the porch, a platfrom for the astronauts to use to get from the hatch to the ladder on the landing gear.

7) Ascent engine Since it was considered disposable, there was no cooling system. Plumbing and other moving parts were kept to a minimum.

8) Thrust chambers Propellant was fired from nozzles in each of the four corners of the craf. These 'reaction control thrusters' were used to make small and precise adjustments to position during flight.

9) Ascent stage Contained the crew compartment, a midsection (housing the ascent engine; navigation, communication and life-support systems) and an equipment bay.

10) Descent stage Accounted for two-thirds of the module's weight. It had a larger engine and more propellant than the ascent stage.

11) Landing gear Since the nature of the lunar surface at the landing site could not be predicted, these were made using crushable honeycomb material in the struts and footpads that could compress on impact.

12) Landing probe Would detect contact with the surface. One on each leg, except for the leg in front of the craft -- that probe was removed so astronauts wouldn't trip over it.

Newsday / Rod Eyer. Sources: Northrop Grumman History Center, Cradle of Aviation Museum, NASA.

The technology

Made for astronauts. Used by you.

Neil Armstrong stepped onto the surface of the moon more than 200,000 miles away from Earth. But today, the products and technology that got him there are in your pocket, medicine cabinet and living room.

Here is a sampling of some of the better-known developments that have had far-reaching consumer impact:

- Technology underlying CT and MRI scanning

- Cool suit technology

- Computer Microchip

- Cordless tools

- Ear thermometer

- Freeze-dried foods

- Home insulation products

- Memory foam

- “Moon boot” materials

- Pulse-generator technology

- Satellite television

- Scratch/shatter-resistant plastic lenses

- Smoke detector and home security systems

Joakim Leroy/Getty Images/iStockphoto

What they ate in space

Americana cuisine goes airborne

Some of the foods the astronauts had on board:

- Coffee (this was the first mission to bring coffee)

- Cornflakes

- Shrimp cocktail

- Salmon salad sandwiches

- Thermostabilized frankfurters

- Scalloped potatoes

National Air and Space Museum

Space Age fashion

How fashion was — and still is — inspired by Apollo

Jumpsuits. Thigh-high skirts. Androgynous looks.

The Space Age, starting with the Soviet Union’s 1957 launch of Sputnik 1 and including the Apollo 11 mission, has had a huge influence on what people have worn on Earth since.

Outer space — representing a new frontier, adventure, endless possibilities and a clean slate — was the perfect fit for a fashion industry increasingly being driven by rebellious young customers bucking tradition and abandoning old dress codes for things that were fresh and new. So, in the 1960s the fashion universe became one of extremes, representing diverse youth movements — with traditional looks colliding with counterculture Space Age, hippie, Carnaby Street, Mod and Beatnik styles.

Designers Pierre Cardin, Andre Courreges and Paco Rabanne began looking to the stars to push the boundaries in their choice of materials and silhouettes, and creations inspired by events such as the moonwalk landed squarely on the catwalk.

Getty Images / Bettmann Archive

Life in 1969

What do so many of us remember about July 20, 1969? Watching TV.

The three TV networks delivered wall-to-wall coverage that day and into the next (TV Guide would later estimate there had been a total of 31 hours of continuous coverage).

CBS was first to get on the air with Apollo coverage at 8:35 a.m. The nation's most popular anchor, Walter Cronkite, would oversee the most-viewed coverage of the moon landing mission, from 11 that morning until Neil Armstrong stepped off the lunar module at approximately 2:12 a.m. Eastern Time the next day.

Viewers had long expected to have the world refracted through Cronkite’s calming and steadfast demeanor. On July 20, they expected nothing less.

Cronkite narrated almost minute-by-minute. For most of those hours Cronkite was joined by astronaut Wally Schirra.

At 4:17 p.m., the module touched down on the moon.

An overwhelmed Cronkite removed his glasses and rubbed the bridge of his nose: '...Boy,' he said. Then, 'Wally, say something. I'm speechless.'

CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

Life in 1969

What we heard and watched

A glimpse of pop culture in 1969

Top song: IN THE YEAR 2525 (Zager & Evans, RCA) Not everyone was comfortable with the technological advances of 1969. This bleak portrait of the future ('In the year 4545, ain’t gonna need your teeth . . . You won’t find a thing to chew') was in the middle of its six-week run at No. 1 for the one-hit wonders.

Popular on TV: ROWAN & MARTIN'S LAUGH-IN (NBC) gave us comedy sketches, antic energy, and plenty of catchphrases that entered the language (and stayed): 'Sock it to me!' 'Here come da judge.' 'You bet your bippy.'

Popular movie: EASY RIDER Few films captured the contradictions of the counterculture like this one. The movie was a cross-generational must-see, and a touchstone for future filmmakers. It was released July 14, two days before the launch of the Apollo 11 mission.

Everett Collection/Columbia Pictures

Life in 1969

Prices have gone up — just a bit

Here's what common items cost on Earth when man went to the moon:

U.S. postage stamp: $.06

Gallon of milk: $1.16

Sticker price of a 1969 Volkswagen Beetle: $1,799

NYC subway ride: $.20

Monthly LIRR Ticket (Huntington-Penn Station): $45.40

Newsday

Life in 1969

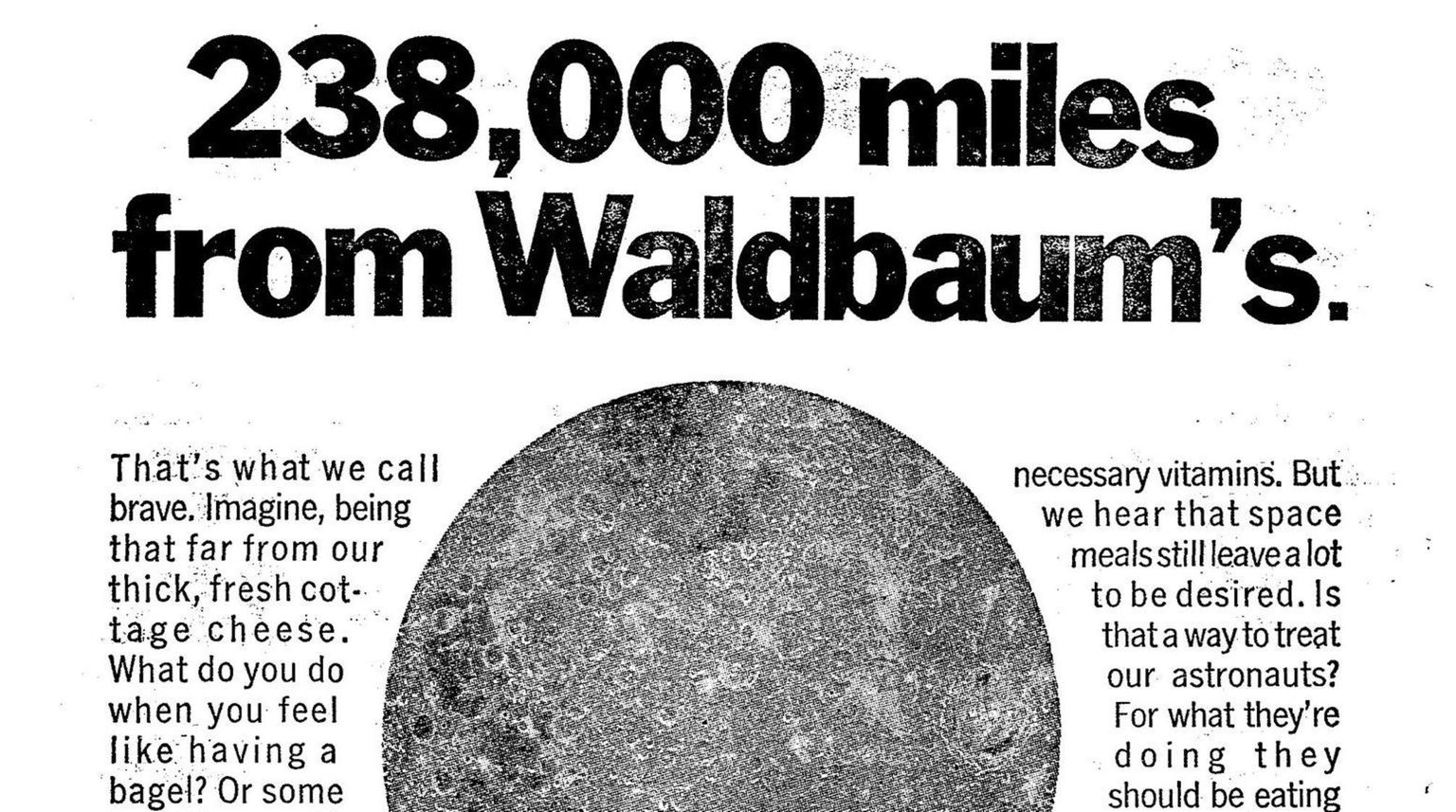

LI businesses look to capitalize on moon landing

What was for sale? A phonograph record of the first words uttered by man on the moon. The watch brand astronauts wore for the moon flight. Twenty three-cent iceberg lettuce. All were featured in Long Island-area promotions by local businesses to help drum up sales during 1969's historic voyage to the moon.

One supermarket touted the event ‘238,000 miles from Waldbaum's.’

The ad pointed out that ‘space meals still leave a lot to be desired’ and that heavenly meals ‘only happen on Earth.’

H.L. Gross & Bro., a jeweler in Garden City, pushed Omega watches for $195 — a pretty penny for 1969 — bragging that NASA leaned on the two-button, four-dial chronographs for space trips.

As for the phonograph record, it was free for anyone who applied for a Marine Midland Master Charge Card.

Click on the photo above to see the ads that ran in Newsday in 1969.

Newsday

The memories

LIers remember the landing: He watched on his Zenith

David Lappin, 64, from East Meadow

Lappin had been hooked on space since 1961, when his kindergarten class watched Alan Shepard orbit Earth.

Lappin was 14 on that summer day. He flipped on the TV in his room, a 12-inch black-and-white Zenith from the Sears in Hicksville that he bought for $100 with his own money and a loan from grandma.

The TV announcer talked about alarms going off in the module, computer problems, and something about the spacecraft maybe running out of fuel. None of it fazed Lappin, who now lives in Charlotte, North Carolina.

'This is no big deal,' he recalled thinking. 'This is NASA. They can do anything.'

Mark Lappin

The memories

LIers remember the landing: She feared disasters

Pat McCullagh, from Sayville

McCullagh was on pins and needles. Her mind kept turning to her husband, Jack.

She was at home with their three kids in Sayville and Jack was in Houston — at Mission Control, on the job as an instrumentation engineer at Grumman.

Lots of their neighbors worked for Grumman, too. And virtually all of Pat's uncles were Grummanites.

'My hopes for the project were many,' said McCullagh, of the moon mission. 'I feared disasters.'

When the module finally touched down, relief and delight.

'I was screaming and yelling,' she said. 'I knew all the hard work they did.'

Danielle Silverman

The memories

Instant heroes

Here’s how some have remembered the Apollo 11 astronauts:

Neil Armstrong, commander

’I think his genius was in his reclusiveness,’ said historian Douglas Brinkley. ‘He was the ultimate hero in an era of corruptible men.’

Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin, lunar module pilot

‘There isn’t a human being in the world who wouldn’t have wanted to be the second man on the moon, but for Buzz, it was almost like being a failure,’ astronaut Gene Cernan said.

Michael Collins, command module pilot

Apollo 11 teammate Aldrin, in the Alamogordo Daily News of New Mexico in 2009, called Collins ‘a great guy, a hard worker and a real team player with a quick sense of humor.’

NASA

The memories

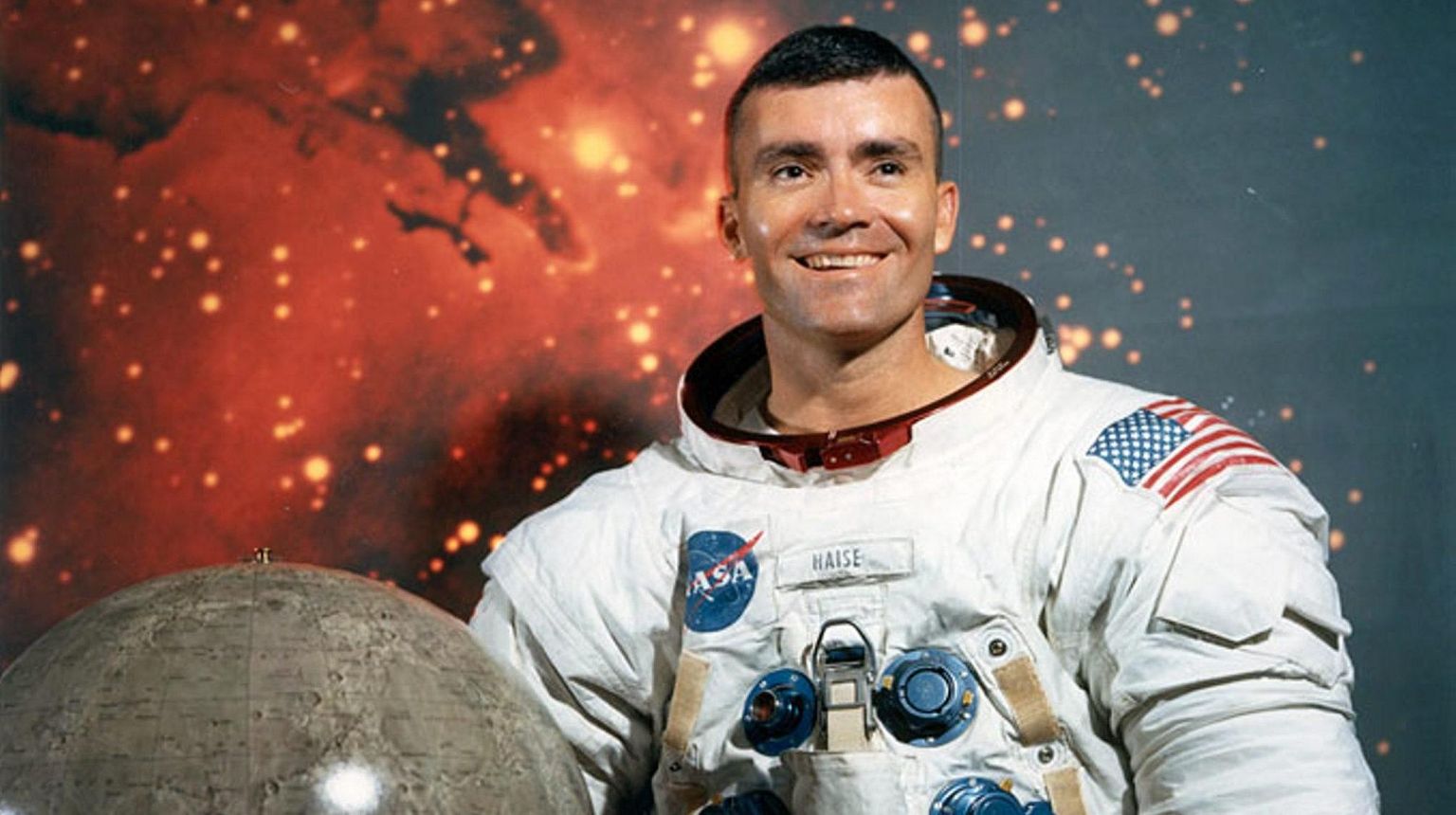

He came within 130 miles of the moon

As a backup for Apollo 11’s Buzz Aldrin, astronaut Fred Haise shadowed him through training, studying and testing for the moon mission, ready to step in.

'It would have been exceptional, obviously, to walk on the moon,' said Haise, 85, who lives in Houston. 'Twelve people got to do it and there's only four still left alive. So it's a pretty small club.'

Still, Haise is one of only 24 Americans who have flown to the moon although he never set foot on its surface. His flight came in April 1970, on the disastrous Apollo 13.

The lunar landing was scrapped two days into the mission when an oxygen tank exploded and crippled the service module. The crew used the lunar module to get home.

For both Apollo 11's launch and the lunar landing, Haise was front and center at Mission Control.

During the module's descent to the moon, alarms in the module sounded: Its computer was overtaxed. Anxiety grew in the room, Haise recalled.

'I wasn't particularly worried at that time because Neil wasn't complaining about the way the vehicle was flying,' Haise said. 'The vehicle was still doing what he wanted it to do, or he would have said so.'

NASA

The memories

Some go up to space. Some arrive on Earth.

For a small contingent of Long Islanders, July 20, 1969, wasn’t just the day a man landed on the moon, it was also when they arrived in the world.

Randi Miller, of East Meadow, was born post-moon landing and just before the moonwalk. The nurses at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New Hyde Park nicknamed her Moonbeam.

Angelina Salerno, of Hicksville, always felt a special connection to the moon. ‘Every time I see a full moon, it speaks to me,’ she said.

To celebrate a half-century on Earth, Miller says she just hopes to wake up at a beach somewhere. Salerno is taking a family trip to Italy this summer.

Matilde Garcia

Reporter reflects

Dad: The Man and the Moon

My Dad was a Grumman man, through and through.

Milty Schneider loved building planes, but his favorite time was working on the lunar module.

With that spider-like spacecraft, my father touched history — much as he did when he served as an Army mortar-gunner in World War II.

Not bad for a kid from Brooklyn, who grew up in an orphanage.

Schneider family

Did you know?

Computer crash

The Apollo 11 mission wasn’t without heart-stopping moments -- Americans just didn’t know about them at the time.

Information overload During the 12.5-minute descent to the moon, the Eagle’s landing computer crashed and recovered five times. Tracking both the Eagle’s landing point and the command module proved to be too much.

Switching things up As Armstrong was getting out of the module, his backpack broke off a circuit breaker needed to blast off the moon. Mission Control came up with a work-around – a computer to fire the engine instead.

Cradle of Aviation Museum

Did you know?

Fun facts

Armstrong talked about the “small step” for man, but his final step down was more of a leap. Armstrong had to hop more than 3 feet from the lunar module’s ladder to the moon’s surface.

For the one night they spent on the moon, Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had to sleep in their helmets and gloves to avoid breathing the moon dust floating around in the lunar module’s cabin.

What does the moon smell like? It depends on who you ask. Neil Armstrong said “wet ashes.” Buzz Aldrin, thought, thought the scent was more like gunpowder or firecrackers going off.

In a nod to the history of flight, Armstrong carried to the moon little pieces of the Wright Brothers’ first plane.

AP

Did you know?

Fuel shortage

The Apollo 11 mission wasn’t without heart-stopping moments -- Americans just didn’t know about them at the time.

Almost on empty Neil Armstrong was caught off guard by all the craters and boulders littering the landing area. He decided to keep flying. By the time he finally found a smooth spot, the lunar module had less than 30 seconds worth of fuel left.

Feelin’ the squeeze Within minutes of setting down, the astronauts noticed pressure rapidly building in a fuel line. An explosion was a real possibility. The cause: Ice, created by the moon’s frigid temperatures. The solution: Heat from the engine, which melted the ice.

NASA

The impact

They watched Armstrong's famous steps. Then they followed his path.

Mike Massimino was mesmerized as he watched the lunar landing. As a 6-year-old, he was already fixated on space.

‘I thought the astronauts were the coolest people around and I wanted to grow up to be just like them,’ he said.

Mary Louise Cleave was 16 when she watched Armstrong’s moonwalk. She too was passionate – for her it was flight.

But she never gave a thought to following in his footsteps. Girls and women didn’t do such things.

‘My parents probably would have sent me to a psychologist if I had said, ‘I want to be an astronaut.’ It was bad enough I wanted to be a pilot.’

But both of them did go into outer space – two of only a half dozen of Long Islanders to have ever done so. Cleave was the 10th woman to fly beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

Looking back, Massimino says even though he was just a young boy at the time, he understood the impact of Apollo 11.

‘I thought it was the most important thing that was ever going to happen in my lifetime and almost the most important thing that was ever going to happen in the world for the next 500 years,’ he said.

‘And I still think that.’

NASA

The impact

LI still a player in space exploration

Long Island is no longer home to major aerospace contractors, but it still has its eyes on the stars. These days its smaller companies on the cutting edge that are keeping the region in the game. To name a few:

Launcher Inc., a six-person startup in Brooklyn, is developing a 60-foot-long rocket powered by a 3D-printed engine. The goal is to deliver satellites as small as a loaf of bread into orbit for less than $10 million per launch.

Hitemco, in Old Bethpage, develops high-temperature coatings that have been used in missiles, rockets, satellites and other aircraft.

And of course Northrop Grumman still has a facility in Ronkonkoma. It’s testing a first-in-the-nation Mach 8 clean-air wind tunnel, and with two other innovation companies forms a hypersonic research triangle within a few miles of Long Island MacArthur Airport.

Newsday / Alejandra Villa Loarca

The theories

Did the government mastermind a fakery?

To this day, millions of Americans think Apollo 11 never landed on the moon — nor any of the other five lunar missions. Did the government mastermind a fakery?

Deniers popped up almost immediately after the Apollo 11 landing, news accounts show. But the conspiracy theories didn't start taking root until the mid-1970s, when a book ‘We Never Went to the Moon’ came out, said Rick Fienberg, a spokesman for the American Astronomical Society.

’This was the time of Watergate, Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers,’ Fienberg said. ‘People began to wonder whether the government was telling them the truth.’

Opinion polls have routinely estimated that 5 percent of Americans don't believe the moon landings happened, Fienberg said. And what about the sheer number of people who would have had to keep the hoax a secret for decades?

’Why would I lie?’ said James Head, who worked at Mission Control. ‘Why would I build a career on this?’

Newsday / Audrey C. Tiernan

Joye Brown

Will the work be remembered?

Did man really land on the moon? Peter Giargente, sitting at his kitchen table, aside a stack of photographs and mementos of his time as a lunar module assembler at Grumman, laughs at the notion of fakery.

And then he says: 'You know, we did have an area in the plant that was made up to look like the moon.'

Giargente was 19 years old when he became a member of the Lunar Module team. He'd be 27 when he left Grumman.

'I talk to my grandchildren about, about what I did, about what other Long Islanders did and about how it was something that had never been done before, he says, wistfully. 'But sometimes I'm afraid that they would be more excited if I had worked on Star Wars, or some other movie about space than what we actually did.'

Johnny Milano