Inside internal affairsAn off-duty Suffolk police officer escaped alcohol testing after a car crash that fractured 2-year-old Riordan Cavooris’ skull.

The department suspended Officer David Mascarella and a second officer in secret, after fellow police gave the DA no way to prove whether Mascarella was intoxicated.

Suffolk police shielded an off-duty officer from alcohol testing after he crashed a pickup truck into the back of a car at an estimated speed of more than 50 mph, fracturing the skull of a 2-year-old boy and causing lasting injuries, a Newsday investigation has determined.

At the wheel of a 4,500-pound Ram truck, Officer David Mascarella rear-ended a 2,000-pound Mitsubishi subcompact on Middle Country Road in St. James in August 2020. A witness reported to police that Mascarella had driven erratically for approximately a mile-and-a-half before the collision.

The Mitsubishi’s driver, Kevin Cavooris, had slowed to make a left turn. His two sons, Bastian, then 4, and Riordan, then 2, were buckled into car seats. Mascarella was multiple car lengths behind them. The police accident report and crime scene diagram reflected no evidence that he braked before the pickup slammed into the Mitsubishi.

A security camera captured the crash that fractured Riordan’s skull. Credit: St. James Star via SCPD

The impact crushed the Mitsubishi’s hatchback area, spun the car 180 degrees into the opposite traffic lane and threw Cavooris’ head into the steering wheel, breaking his nose. Bastian’s thighs, shoulders and chest were bruised by the car seat’s harness. Riordan’s skull cracked into pieces resembling a jigsaw puzzle. The Ram continued forward with little damage.

Security cameras at four businesses along Middle Country Road recorded the moments immediately before the crash; the impact and rescue efforts; and the actions of Mascarella and police officers after he drove away from the scene and into the parking area of a car dealership 400 feet down the road.

Watch the video report

The Suffolk County Police Department gave the video recordings to a Cavooris family attorney in response to a Freedom of Information Law request. They were on discs in formats that were not readily viewable. Newsday made the recordings playable for the family.

The department also turned over to the family police documents, including accident reports, photos of evidence and sworn statements from five witnesses and six officers.

Cavooris and his wife, Valerie, provided the videos and police records to Newsday’s Inside Internal Affairs project after being contacted about the case. They said they hoped to find out what has never been explained to them: how the department investigated a high-speed crash that harmed Riordan’s development, requiring him to relearn how to feed himself and perform other activities of a toddler.

Almost two years after the crash he uses a leg brace to walk and is unable to run or jump.

“Riordan deserves answers because he was wronged,” Kevin Cavooris said.

From the editors

Long Island’s two major police departments are among the largest local law enforcement agencies in the United States. Protecting and serving, the Nassau and Suffolk County police departments are key to the quality of life on the Island – as well as the quality of justice. They have the dual missions of enforcing the law and of holding accountable those officers who engage in misconduct.

Each mission is essential.

Newsday today publishes the sixth in our series of case histories under the heading of Inside Internal Affairs. The stories are tied by a common thread: Cloaked in secrecy by law, the systems for policing the police in both counties imposed little or no penalties on officers in cases involving serious injuries or deaths.

This case documents that Suffolk police shielded an off-duty officer from alcohol testing after he drove a pickup truck into the rear of a nearly stopped car at more than 50 mph, fracturing the skull of a 2-year-old and causing lasting injuries.

Three hours after the crash, Officer David Mascarella refused to submit to a breath test. The police then failed to seek a warrant to test his blood alcohol level. Without that test, the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office was unable to determine whether Mascarella had been drinking before the crash – ruling out a possible vehicular assault prosecution.

The child’s name is Riordan Cavooris. The crash happened in 2020. Since then, Riordan’s parents, Kevin and Valerie Cavooris, have tried to discover what led Mascarella to drive into their car – as well as whether the Suffolk County Police Department had held him accountable.

Contacted by Newsday, the Cavoorises gave reporter David Schwartz copies of police documents obtained in response to a Freedom of Information Law request along with security camera recordings that captured a sequence of events starting moments before the crash and extending to police interactions with Mascarella.

Based on Schwartz’s reporting, the Cavoorises learned for the first time that then-District Attorney Tim Sini had closed a criminal investigation without action; that a second officer, Kevin Wustenhoff, falsely reported Mascarella had passed a breath test, according to a source with direct knowledge of the investigation; and that county payroll records revealed Suffolk Police Commissioner Rodney K. Harrison suspended Mascarella and Wustenhoff without pay in February.

Wustenhoff’s suspension covered 45 days, while Mascarella remained suspended as of Aug. 17, according to the payroll records. An aide to the commissioner asserted that Harrison was legally barred from discussing the results of the department internal affairs investigation.

This case history is the second in which Suffolk police protected off-duty officers from alcohol testing after they drove into crashes that caused serious, even life-threatening, injuries. In both instances, Suffolk County Police Benevolent Association representatives drove the officers away from investigators at the scene; the officers refused to submit to breath testing; and police failed to take additional steps to determine whether the officers were intoxicated.

Newsday has long been committed to covering the Island’s police departments, from valor that is often taken for granted to faults that have been kept from view under a law that barred release of police disciplinary records.

In 2020, propelled by the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the New York legislature and former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo repealed the secrecy law, known as 50-a, and enacted provisions aimed at opening disciplinary files to public scrutiny.

Newsday then asked the Nassau and Suffolk departments to provide records ranging from information contained in databases that track citizen complaints to documents generated during internal investigations of selected high-profile cases. Newsday invoked the state’s Freedom of Information law as mandating release of the records.

The Nassau police department responded that the same statute still barred release of virtually all information. Suffolk’s department delayed responding to Newsday’ requests for documents and then asserted that the law required it to produce records only in cases where charges were substantiated against officers.

Hoping to establish that the new statute did, in fact, make police disciplinary broadly available to the public, Newsday filed court actions against both departments. A Nassau state Supreme Court justice last year upheld continued secrecy, as urged by Nassau’s department. Newsday is appealing. Its Suffolk lawsuit is pending.

Under the continuing confidentiality, reporters Paul LaRocco, Sandra Peddie and Schwartz devoted more than 18 months to investigating the inner workings of the Nassau and Suffolk police department internal affairs bureaus.

Federal lawsuits waged by people who alleged police abuses proved to be a valuable starting point. These court actions required Nassau and Suffolk to produce documents rarely seen outside the two departments. In some of the suits, judges sealed the records; in others, the standard transparency of the courts made public thousands of pages drawn from the departments’ internal files.

The papers provided a guide toward confirming events and understanding why the counties had settled claims, sometimes for millions of dollars. Interviews with those who had been injured and loved ones of those who had been killed helped complete the forthcoming case histories and provided an unprecedented look Inside Internal Affairs.

Three attorneys, each with more than a decade’s experience with car-crash and drunken-driving investigations, reviewed a case file prepared by Newsday. Independently, they concluded that police officers who responded to the crash broke protocols that are designed to identify the causes of serious vehicular collisions.

‘… they did not do a diligent, reasonable, defensible investigation.’

Former state trooper and prosecutor John BandlerCredit: Reece T. Williams

“I know based on what I’ve seen, they did not do a diligent, reasonable, defensible investigation,” said John Bandler, a former state trooper who served as a prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office for 13 years.

“And that’s really unfortunate because when any casual observer looks at the facts of this case and the investigation, a casual observer is going to think that the police department gave a benefit to this off-duty cop.”

Referring to the quality of the police investigation, John T. Powers, a West Islip-based lawyer who represents clients charged with drunken-driving offenses, said, “In my experience over 20 years, I’ve never seen anything like this.”

“No other individual would get the same deference,” Powers added, speaking of Mascarella.

Two-year-old Riordan Cavooris started long recovery after off-duty Suffolk officer crashed pickup into family car.

Watch and ReadBrian Griffin, a former Nassau assistant district attorney assigned to the drunken-driving prosecution unit, has represented drivers accused of vehicular crimes and driving while intoxicated.

“Normal procedures/protocols were not followed,” he wrote in an emailed statement, adding that “the more important question is whether these lapses . . . were intentional and negatively impacted the investigation.”

Mascarella was assigned to the Fourth Precinct in Smithtown. Fellow precinct officers and a sergeant responded to the crash and handled the initial investigation. A deputy inspector later took command. Newsday determined that:

- Sgt. Lawrence McQuade and precinct officers failed at the scene to ask Mascarella to submit to a breath test that would have provided a preliminary reading of whether he was intoxicated.

- After a detective told McQuade that he wanted Mascarella to undergo a preliminary breath test, McQuade notified a Suffolk County Police Benevolent Association delegate. The delegate, Officer Joseph Russo, then drove Mascarella away from investigators, McQuade reported.

- Ordered to catch up with Mascarella, Fourth Precinct Officer Kevin Wustenhoff falsely reported to a supervisor that he had given Mascarella the breath test and that Mascarella had passed it, according to a law enforcement source with knowledge of the case. Wustenhoff retracted the account, the source said.

- Three hours after the crash, Deputy Insp. Mark Fisher asked Mascarella to take the breath test. Mascarella refused. When a driver refuses a preliminary breath test, police typically seek a warrant to have the driver’s blood drawn and tested for alcohol. Fisher only issued a traffic ticket to Mascarella.

- Police failed to notify the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office on the night of the crash that an officer had been involved in an unexplained, high-speed rear-end crash, had seriously injured a 2-year-old and had refused a breath test. The omission prevented the DA from considering whether to seek a warrant to test Mascarella’s blood.

- Although five officers wrote reports stating they saw no evidence that Mascarella was intoxicated, prosecutors under then-DA Tim Sini subsequently investigated the crash with an eye toward charging Mascarella with vehicular assault. Lacking a blood test that would have revealed whether Mascarella was intoxicated, they closed the investigation without action.

“The failure to get a prompt chemical test handcuffed the prosecutor,” Powers said. “At that point, the prosecutor is coming up on the barn with the door open and there’s no animals in the barn. It’s a day late.”

Newsday sought comment from former DA Sini, his successor Ray Tierney, Police Commissioner Rodney K. Harrison and Mascarella’s lawyer, William Petrillo.

Sini and Tierney responded that the investigation, handled by police in the crucial hours after the collision, failed to produce the evidence necessary to determine whether Mascarella had been drinking.

Tierney wrote in an emailed statement: “Because certain evidence was not collected by SCPD on the date of the incident, we were unable to make a determination as to whether or not a crime was committed.”

Tierney also wrote that he had met with Harrison “about the failures in the prior investigation,” stating, “It is my expectation that any future SCPD investigations of incidents such as this will be conducted properly with guidance from my office.”

Sini wrote in an email: “The absence of certain evidence prevented the Office from determining whether a crime was committed.”

Harrison stated that he is establishing policies aimed at preventing police from giving special treatment to off-duty officers. He declined to comment on the specifics of the case. A spokesperson for the department wrote that Harrison is moving to terminate Mascarella.

Petrillo asserted that the district attorney’s investigation “correctly concluded that no crime was committed.” He stated that “alcohol was not a factor” in the crash and added that a doctor and physician assistant at the hospital, along with a witness at the crash site and officers, “reported seeing no signs of alcohol consumption or impairment.”

Newsday informed Cavooris about its findings and enabled him for the first time to watch the four security camera videos. Those captured events from the moments before the collision through Mascarella’s departure with a PBA delegate — and included evidence that Mascarella threw an object from the Ram’s window seconds after the crash.

Cavooris said he had not known about investigations by the Suffolk internal affairs unit and the district attorney’s office before being informed by Newsday. He said he also knew nothing about Wustenhoff’s reported role.

“There are things we should know that are being withheld from us,” Cavooris said. “We want to forgive, and we want to live in the moment and not dwell on the past, but it’s impossible to move on until we get the answers that some people have and are not telling us.”

Records reveal officers suspended without pay

In December last year, Newsday began to publish case histories documenting that the internal affairs systems of the Nassau and Suffolk County police departments had imposed little or no discipline on officers in cases involving serious civilian injuries or deaths. This is the sixth case history.

Harrison took command in Suffolk on Jan. 11. His assistant said the department’s legal bureau advised Harrison against discussing Mascarella’s case.

Still, county payroll records revealed that Harrison suspended Mascarella and Wustenhoff without pay on Feb. 3 — a week before the deadline for filing disciplinary charges against them. Wustenhoff’s suspension ended 45 days later on March 21, according to the county comptroller’s office. Mascarella remained suspended as of Aug. 17.

For a half century, police disciplinary files in New York were sealed by law. In 2020 following the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis officer, state legislators and then-Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo repealed a law known as 50-a that had imposed near-total secrecy on police disciplinary files.

The Nassau County Police Department has claimed continuing power to withhold almost all internal disciplinary records. The Suffolk County Police Department has released records only in cases where charges had been upheld against officers.

Newsday is pressing lawsuits against both departments with the goal of establishing that the public has a right to review how Long Island’s police forces police themselves.

On March 16, Newsday asked the Suffolk department to release internal affairs records related to the crash that injured Riordan Cavooris. The department replied that it would make the records available on or about June 14.

The date came and went without additional communication. In other cases, the department has delayed releasing records for as much as a year.

‘I feel cheated and lied to, denied justice and victimized again.’

Kevin CavoorisLearning Newsday’s findings almost two years after the crash, Cavooris said:

“I feel cheated and lied to, denied justice and victimized again.”

Reached by telephone, Wustenhoff referred questions to his attorney, Anthony La Pinta.

La Pinta called the account that Wustenhoff falsely reported that Mascarella had taken and passed a PBT “incorrect.”

La Pinta wrote in an email: “The charges were resolved between the department and Officer Wustenhoff. I am unable to comment further because Officer Wustenhoff’s IAB file remains sealed and a related IAB investigation is pending.”

Fisher and Russo did not respond to interview requests. McQuade declined to comment through Suffolk County Superior Officer Association president James Gruenfelder.

The source with knowledge of the investigation said that Wustenhoff resolved the internal affairs investigation by accepting his suspension and placement on restricted duty, which took him off patrol. He was assigned to police administrative duties at the John P. Cohalan Jr. Court Complex in Central Islip.

The department permitted Wustenhoff, 45, to stay on the police payroll until 2025, when he will first be eligible to retire with a 50% pension that he could begin collecting immediately. He agreed to resign then, the source said.

The police contract empowered Wustenhoff to challenge stricter penalties, potentially including dismissal, in arbitration. Wustenhoff was paid $176,177 in 2021.

Mascarella, 52, made $250,954 in 2021. At the time he was suspended, he was a year from being able to retire and collect his pension immediately.

Sudden horror on ordinary day

Kevin Cavooris, then 33, picked his sons up from a day-care center after work on Monday, Aug. 10, 2020. He held a job as a supervisor at Long Island Adventure Park in Wheatley Heights while completing graduate studies at Baruch College. He buckled Riordan and Bastian into their car seats for the 2-mile drive to their St. James home.

The route took Cavooris east on a stretch of Middle Country Road lined by automobile dealerships. Double yellow lines separated two lanes. The speed limit was 40 mph. Traffic moved smoothly on a sunny afternoon.

The crash occurred on Middle Country Road in St. James. Credit: Jeffrey Basinger, Google

Mascarella traveled the same stretch. So did John Melendez, owner of a junk removal company. At the wheel of another pickup and towing a trailer, Melendez came up behind Mascarella’s black Ram approximately a mile and a half from the crash scene. The Ram’s driver had slowed down, holding up traffic, Melendez told police.

“He was driving slower than the traffic in front of him like he was not paying attention,” Melendez reported. “He was holding me up and the cars behind me. The traffic was moving, he was not moving and there were no cars in front of him.”

The Ram’s driver accelerated for a stretch and slowed again, accelerated, and slowed again, Melendez reported.

Concluding that the driver was on a cellphone and distracted, Melendez edged his truck left toward the road’s dividing lines. He hoped that the driver would spot him in the Ram’s sideview mirror. The driver appeared not to notice.

Ahead of Mascarella, Cavooris prepared for a legal left turn that would take him off Middle Country Road and into a tree-shaded neighborhood of single-family houses. To make a left there, a driver slows or stops at a break in the double yellow lines to cross traffic coming in the opposite direction.

Cavooris recalled that he clicked on his turn signal and checked his rearview mirror. He judged that the driver behind him had time to slow and safely pass on the road’s black-topped shoulder.

“Perfectly normal mundane driving things,” Cavooris recalled.

Beyond Cavooris’ field of vision, Melendez again attempted to get the attention of the Ram’s driver, this time by honking his horn.

At the sound, the driver “punched it” and the pickup “accelerated quicker,” Melendez told police. He judged that the truck traveled about 12 car lengths before there was a loud bang.

Mascarella follows Cavooris into the crash. Credit: Certified Headquarters via SCPD

Newsday estimated Mascarella’s approximate speed, as well as the speeds of other drivers, including Cavooris, by measuring the lengths of the roadway captured by two cameras and clocking how much time elapsed as each vehicle passed.

Carl Berkowitz, a Moriches-based traffic engineer who reconstructs vehicular crashes for court cases, said Newsday’s methodology of estimating speeds was standard.

“It’s consistent with what I would do,” he said.

A 10th of a mile from the crash intersection, a Mazda dealership’s security camera captured 250 feet of the road. Newsday estimated the speeds of 20 cars that crossed the camera’s field of vision ahead of Cavooris and Mascarella.

Those measurements showed that Mascarella was driving 67% faster than the average speed of the 20 cars ahead — an estimated 60 mph compared with an approximate average speed of 36 mph.

The security camera at a used car dealership then recorded traffic on 150 feet of the road immediately approaching the crash site. Here, 20 cars passed at approximately 32 mph, followed by Cavooris slowing to a near stop and by Mascarella moving at approximately 55 mph in the moments before he drove the Ram into the Mitsubishi, according to Newsday’s estimate.

He said that Newsday’s calculation matched his belief that Mascarella had hit his car at high speed.

“I assumed from the force of impact he had to be going over 50 miles per hour,” Cavooris said.

With its rear crushed, the Mitsubishi spun across the opposite lane of traffic. Melendez described the motion as looking like the Ram had “spit the white car from the front of the truck.”

Cavooris said he doesn’t remember his face hitting the steering wheel.

“My mind was saying, ‘I’m fine. Bring this vehicle to rest. Make sure the kids are fine,'” he recalled.

The Mitsubishi rolled backward to a stop in front of the St. James Star gas station. Mascarella continued down the road. Damage was limited primarily to the truck’s front driver’s side. The truck’s air bag had not deployed.

Cavooris stumbled from his car, blood coming from his nose.

Ron Brandt was filling his tank. He rushed over with his wife, Laurene.

“It was a pretty violent hit where we thought we were going to get hit by the car rolling,” Brandt said.

The Brandts motioned for Cavooris to sit. He said his kids were in the back seat. Someone called 911. People ran from nearby businesses. Brandt, wearing a COVID mask, yanked open a rear door and lifted Bastian from the wreck.

“My brother, my baby brother,” Bastian screamed.

Brandt saw Riordan as he lifted Bastian.

“He was unresponsive. His head was down,” Brandt recalled.

The door beside Riordan was crumpled. The car shook as one man, then two, tried to pull it open. A third man came with a crowbar. Five men in all tried to force the door open without success.

Cavooris was on his feet again. He leaned into the car where Riordan was still in his car seat. He squeezed Riordan’s hand. Riordan was unresponsive. A woman identifying herself as a nurse said Riordan had a heartbeat and was breathing.

Brandt held Bastian in his arms. Laurene Brandt rubbed Bastian’s back. A man brought Cavooris water and a towel for his face.

Someone handed Cavooris a cellphone. He called his wife. Her father-in-law drove Valerie to the crash site, about a mile-and-a-half from home.

“I’m not ready for this,” she recalled telling him on the way.

“I know,” he responded.

Valerie reached the scene 12 minutes after the crash.

Nesconset firefighters place unconscious Riordan Cavooris on a stretcher. Credit: St. James Star via SCPD

“I screamed, I screamed, ‘Where’s my son?'” she recalled.

A Nesconset Fire Department heavy rescue team was cutting open the Mitsubishi. Within minutes of Valerie’s arrival, they gained access to Riordan and stabilized his neck. He was still unconscious. Fifteen minutes after the crash, two firefighters carried his limp body from the car and placed him on a stretcher.

Valerie faced a choice — stay with Bastian, who was upset and bruised from the impact, or go with Riordan to the Stony Brook University Hospital emergency room, five miles away.

“I felt horrible leaving Bastian’s side because he was terrified,” she remembered. “But I knew that I had to go with Riordan so that he would have someone there when he got to the hospital.”

She jumped into the ambulance.

“And I just prayed the whole way there. Please don’t take my baby,” Valerie said.

Watching the video, Cavooris said he took heart from the sight of people trying to help.

“It’s reassuring to have faith in humanity that people see something awful, and they want to help,” he said. “They want to jump into action.”

Police questioned Cavooris at the scene about how the crash had happened. He remembered that officers asked why his car was facing west when he had been driving east and that they pressed him to pinpoint the street where he was turning.

Officers also asked where Cavooris was coming from and where he was going — questions that police typically ask at the start of a possible drunken-driving investigation to discover whether a driver had come from a location where alcohol is typically consumed, such as a bar, restaurant or party.

Cavooris said the questions “I specifically remember were more about where I was going and what I was doing.” He assumed the driver who rear-ended his car would face similar questioning.

“I think certainly he was involved in an accident, and he deserves to be asked about his medical well-being,” Cavooris said. “And beyond that, to the extent he’s capable, it would be the time to seek answers as to what exactly happened and why it happened.”

The police records given to the family include no indication that officers questioned Mascarella about the circumstances leading up to the crash and the factors that caused him to drive the Ram into Cavooris’ nearly stopped car. The records reflected Cavooris’ description of turning but included none of his additional statements at the scene.

‘I want to know what he threw.’

After the crash, Mascarella slowed and an object flew from the passenger window. Credit: St. James Transmissions via SCPD

About nine seconds after rear-ending the Mitsubishi, Mascarella slowed to a stop approximately 300 feet from the crash site in the field of vision of a transmission shop’s camera.

The camera recorded an object flying from the Ram’s passenger window.

Seconds later, Melendez pulled his truck next to the Ram. In the statement he gave police, he recounted shouting obscenities at Mascarella “for being on the phone.”

“That’s what you get, are you happy?” he yelled.

The driver looked at Melendez “like he was scared or didn’t know what happened, like a look of confusion,” Melendez told police.

Melendez drove on. He did not respond to requests for comment,

Mascarella pulled a short distance forward into the parking area of a Chevrolet dealership, out of sight from the scene of the crash. He got out of the Ram and spoke on a cellphone. Two minutes after the crash, he walked toward the road, bent down, appeared to pick up the object that had flown from the truck window, and returned to the pickup.

“I want to know what he threw from his vehicle,” Cavooris said while reviewing the video. “I want to know why, after an accident like that, your mind would find it so important to get that item out of your vehicle, and then, with a chance to collect himself and make a phone call and clear his head a little, he realizes he needs to retrieve that item.

“And all this time he’s concentrating on whatever that item is, he doesn’t appear unwell. He seems perfectly capable of checking on the family that he caused such harm to. Apparently, his only concern was whatever that item is.”

Brandt, who’d lifted Bastian from the Mitsubishi, saw Mascarella’s truck pull to the shoulder. He glanced again after a few moments and the truck was gone.

“And then with all the commotion we looked around and it’s like, ‘Where the hell’s this truck?'” Brandt said.

Fourth Precinct officers reached the crash scene in four minutes. Mascarella walked toward his colleagues. He wore a light-colored polo shirt and shorts. One of the first responding police officers was positioning a squad car in the roadway to divert traffic around the Mitsubishi.

Riordan was still trapped in the car. Bastian was still in the arms of a stranger. The Nesconset rescue personnel had yet to arrive. Mascarella spoke to the officer in the squad car for approximately 10 seconds, then returned to his pickup at the car dealership.

Suffolk police regulations direct officers “to keep the drivers in sight and available” after crashes. The rule is aimed at preventing drivers from fleeing, destroying evidence or explaining failed breath tests by claiming they had consumed alcohol after crashes and not before.

“I don’t know any other circumstance in my career, and it’s over 20 years of handling these cases, with serious physical injuries, where I’ve ever heard that my client or a motorist was allowed to remain a football field and a half away,” Powers said.

Robert Brower, who worked in sales at the car dealership, spoke briefly with Mascarella. He later reported that Mascarella was talking on a cellphone while sitting on a curb and did not appear intoxicated.

At the crash site, Brandt asked police about the truck that appeared to have vanished. Officers responded, “What truck?” he recalled.

Brandt crossed the street with police.

“We all walked over and found out that the guy pulled over into the Chevy dealership on the other side of the building,” Brandt said, adding of Mascarella: “He actually moved the truck before the police arrived, which seemed very weird.”

The first uniformed officer approached Mascarella 10 minutes after the crash. Two additional officers followed. The three stood a few feet from Mascarella and appeared to speak with him.

Over the next hour, officers came and went from talking with Mascarella. He paced, walked around the parking area, sat on the curb and spoke on a cellphone. Officers left him alone for 16 minutes during that time. The camera recorded him opening one of the Ram’s doors and leaning into the pickup 10 times while officers were with him or when he was alone.

Bandler said leaving Mascarella alone violated standard training for drunken-driving investigations.

“If there’s the possibility that you’re investigating them for driving while intoxicated, you need to continually observe them, you can’t allow them to walk off on their own,” Bandler said. “Part of a DWI investigation is you’re continually observing someone.”

Officer Terence Greene wrote in a report dated the day of the crash that he recognized fellow officer Mascarella and asked if he was injured or needed medical attention. He stated that Mascarella replied, “No, I’m fine, how is everyone else?”

Greene reported no additional questioning, described no observations of Mascarella for signs that he had consumed alcohol, such as glassy eyes, unsteadiness or the odor of alcohol. He gave no assessment of whether Mascarella showed evidence of intoxication.

Officer Christopher Antola reported the day of the crash that the driver, a fellow precinct officer, identified himself as David Mascarella. Asked whether he needed medical attention, Mascarella said “He was okay for now,” Antola wrote.

Antola, too, reported no additional questioning, described no observations of Mascarella and gave no assessment of whether Mascarella showed evidence of intoxication.

Officer Nicholas Cutrone filled out a state Department of Motor Vehicles Police Accident Report. His report is the only document in the file indicating that an officer asked Mascarella on the day of the crash what happened.

Designating the Mitsubishi as “V1,” meaning “Vehicle 1” and the Ram as “V2,” meaning “Vehicle 2,” Cutrone wrote only that Mascarella “states he was traveling [eastbound] on Route 25 when V2 collided with V1.” He checked a box on the form citing “driver inattention/distraction.”

Greene, Antola and Cutrone did not respond to interview requests.

Bandler and Powers said that proper practice called for immediately investigating whether alcohol had played a role in the crash. They cited the facts that Mascarella had rear-ended a car and had been traveling at a high enough speed to cause both extensive damage and serious physical injury — a legal standard that triggers a possible criminal charge of vehicular assault.

Both said that the circumstances of the collision called on the responding officers to take a statement from Mascarella, document efforts to observe evidence of intoxication and request that he undergo both field sobriety testing and a preliminary breath test. Griffin said police had grounds to ask Mascarella to take a preliminary breath test.

Field sobriety testing requires a driver to perform actions such as walking heel-to-toe in a straight line and balancing on one leg.

In a preliminary breath test, also known as a portable breath test, a driver blows into a hand-held device that measures a body’s alcohol level. A preliminary breath test is different from a test commonly known as a Breathalyzer. Breathalyzer results are admissible in court; a preliminary breath test is not.

When a driver refuses to take a preliminary breath test, police typically take the driver into custody and seek a warrant to have a sample of the driver’s blood drawn for a blood alcohol test.

“The smashed and rear-ended car, the children in the car, indicate towards assuming the ‘worst’ and preserving evidence and erring on the side of doing a thorough investigation,” Bandler wrote in an email. He later said:

“This is not a situation where you’re not thinking about the possibility of intoxication. This is something you actively need to determine. And you need to determine quickly because if he was intoxicated, his blood alcohol content is dropping every minute.”

Powers said: “Heavy damage to the car, injury — a serious injury — to the passenger in the car, would prompt a further investigation in this case up to and including what’s called a PBT or a portable breath test at the scene of the driver.”

A child’s skull rebuilt

At Stony Brook University Hospital, pediatric neurosurgeon Dr. David Chesler explained to Valerie Cavooris that Riordan had suffered complex skull fractures, with part of the skull pressing on his brain.

Chesler needed to “put the skull back together like a puzzle,” she said. “It was totally fractured.”

Kevin Cavooris, who was with Bastian, spoke with Chesler by phone.

“He had to clean off the brain and reconstruct the skull around it,” said Cavooris, who rode with Bastian in an ambulance to the hospital, where the doctors examined the boy for neck and shoulder pain and bruises.

‘He had to clean off the brain and reconstruct the skull around it.’

Kevin CavoorisThat night, officers asked Cavooris to submit to a breath test and consent to have blood drawn for alcohol testing. Cavooris remembered that a detective told him:

“You have a long road ahead of you, of lengthy legal proceedings and lawyers being involved. You don’t want anything derailing what you’re going through, if anyone makes accusations against you.'”

Cavooris blew into the breath device. It registered zero. The officers told him they didn’t need to draw blood.

At that point, Cavooris knew nothing about the driver who smashed into his car. He and Valerie had no idea, and were not informed, that the driver was a Suffolk County police officer. Cavooris remembers presuming that police were using the same procedures to investigate the driver.

“Was he impaired? Was he distracted? Did he lose control of his vehicle? Did he suffer a medical incident that caused him to cause an accident? I trusted the police. If they were there to see me, then my assumption was there were police seeing him,” Cavooris recalled, adding,

“I probably just assumed they’d be doing their jobs.”

Two-year-old Riordan was still unconscious when the ambulance drove away from the crash site. Sgt. McQuade ordered two officers to go to the hospital to confirm whether Riordan had suffered a serious physical injury, the condition necessary for a vehicular assault charge.

New York’s Penal Law defines a serious physical injury as an injury that creates “a substantial risk of death” or causes long-term body harm.

An hour after the crash, an officer relayed confirmation from the medical center that Riordan had suffered serious physical injuries. Only then did McQuade call for a detective to take charge of the investigation.

Bandler faulted the delay, noting that a severe impact had rendered a 2-year-old unconscious.

“You don’t delay your investigative action, waiting for a determination of serious physical injury,” he said.

Mascarella refuses breath test

Fourth Precinct Det. James Ellis came to the scene. Ellis determined that Mascarella should undergo a preliminary breath test because of “the severity of the injuries” suffered by Riordan, McQuade reported. Ellis did not respond to interview requests.

Standard practice calls for officers to simply ask a driver to perform the test. McQuade instead called Russo, the PBA delegate. McQuade wrote that Russo had joined Mascarella at the car dealership and he told Russo that Ellis wanted Mascarella to submit to a breath test.

“I advised I would be at his location in five or ten minutes and administer the test there,” McQuade wrote.

The security camera recording shows that a dark car pulled into the parking area an hour and 47 minutes after the crash. The driver got out and opened the trunk. Mascarella talked to the driver and to a uniformed officer. The officer walked away. Mascarella got into the car. The car drove off an hour and 50 minutes after the crash.

McQuade wrote that he learned as he walked toward the car dealership that Mascarella had left. He didn’t explain how he was notified.

“I immediately called PO Russo via cellphone and informed him he should respond back to the accident location,” McQuade wrote. “He informed me that David Mascarella was in significant pain and needed to go to the hospital.”

Russo drove Mascarella to Southside Hospital, 15 miles away, the fifth-farthest hospital.

Griffin described moving Mascarella as “very problematic.”

“A lay person is not going to have an HR representative in the middle of an investigation, period, end of story,” he said.

Powers said that driving Mascarella away from a planned breath test could be seen as tampering with a witness or tampering with evidence.

‘The whole thing stinks of organizational conflict.’

Drunken-driving defense attorney John T. PowersCredit: Alejandra Villa Loarca

“The whole thing stinks of organizational conflict. At the very least again it erodes the public’s trust in law enforcement, bit by bit and step by step,” he said.

Bandler blamed police at the scene for allowing Mascarella to leave.

“I think it’s incriminating as to the reasonableness of the police department’s investigation that they would let someone who they should have suspected might be intoxicated, that they would let him drive off,” Bandler said.

Russo and PBA president Noel DiGerolamo did not return requests for comment.

Deputy Insp. Fisher arrived at the crash site. McQuade reported that Mascarella’s actions showed “no indication of criminality,” signaling that officers had evaluated Mascarella for evidence of alcohol consumption and that the results were negative.

“Nevertheless, I ordered the administering of a Pre-breath Test (PBT) to Mascarella,” Fisher wrote.

McQuade directed Wustenhoff, a former highway patrol officer, to administer the exam at the hospital and to take a photograph of the device’s readings.

Wustenhoff wrote in a report that he arrived at the hospital at 7:20 p.m., found Mascarella in the emergency department complaining of back pain, and saw “no indication of alcohol use.”

He called McQuade, stating falsely that he had tested Mascarella and that the device had registered zero alcohol traces, the source with knowledge of the investigation said.

About eight minutes later, Wustenhoff made a second call to McQuade, said he misspoke and asked to retract his earlier statement. McQuade told Wustenhoff he lied, according to the source.

Neither McQuade nor Wustenhoff included Wustenhoff’s retracted statement in their written reports.

The district attorney’s investigation later discovered that a hospital security camera recorded Mascarella walking up and back as if he was taking a sobriety test, the law enforcement source said.

“It was like he was practicing,” the source said.

Fisher drove to the hospital. While on the way, he wrote, he decided to rely on a highway patrol lieutenant, rather than Wustenhoff, to perform the breath test “to avoid any appearance of impropriety,” possibly alluding to the fact that Wustenhoff and Mascarella were fellow Fourth Precinct officers.

Fisher notified Highway Patrol Lt. Peter Reilly to meet him at the hospital.

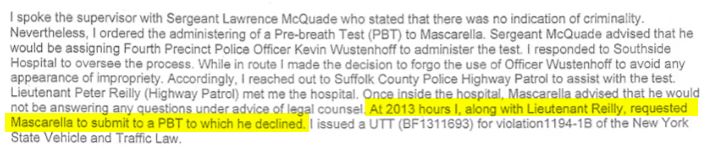

‘At 2013 hours I, along with Lieutenant Reilly, requested Mascarella to submit to a PBT to which he declined.’ Report by Deputy Insp. Mark Fisher

Around 8 p.m. — three hours after the crash — Mascarella twice refused to take the breath test.

First, Ellis asked Mascarella to allow Wustenhoff to administer the exam, Wustenhoff wrote. Then, Reilly and Fisher made the request, according to Fisher’s account. Each time Mascarella said no. Mascarella also declined to answer questions under the advice of legal counsel.

At 10:45 p.m. — six hours after the crash — Fisher issued Mascarella a traffic ticket for refusing a breath test, according to Wustenhoff’s report. He took no additional action.

Fisher wrote that there were “no overt indications of intoxication other than [Mascarella’s] eyes appearing somewhat glassy.”

When a driver refuses a breath test, police can arrest the driver and ask a judge to issue a warrant authorizing a blood alcohol test. Bandler said that refusing a breath test gives police evidence for a warrant application.

“If he says, ‘No, I’m not taking a PBT,’ then the officer is going to use some common sense and say maybe the reason he’s not taking a PBT is because he knows he had alcohol,” he said. “So, then you err on the side of arresting them.”

Powers said that Suffolk police typically force drivers to submit to blood testing when they refuse breath tests after unexplained crashes that cause serious injuries.

“If he’s saying no to a PBT, they then can go and get a warrant. They have the reasonable cause, and probable cause, to get a blood warrant, to get a blood draw issued by the court. A mandated blood draw,” Powers said. “In this case, with that kind of injury, that is par for the course for Suffolk County Police. They do it all the time.”

Powers added: “You have the puzzle pieces here for an arrest. You just need a competent police officer to come and do a reasonable and competent investigation.”

Suffolk protocols mandate that police must notify the district attorney’s Vehicular Crimes Bureau when officers see evidence of criminality in crashes that cause serious physical injury or death. Police did not contact the district attorney’s office on the night of the crash.

Powers said police were obligated to ask a prosecutor to decide how to proceed after Mascarella refused the breath test.

“The on-duty ADA catching cases that day should have been notified without a doubt. There was no reason not to have the case and fact pattern evaluated by the Office of the District Attorney,” he wrote in an email.

Bandler said an outside agency — whether the DA’s office, Nassau police or state troopers — could have ensured public confidence in the investigation.

Griffin said that if police saw evidence of criminality “they clearly did not follow protocol when they failed to alert the DA’s office Vehicular Crime Bureau.”

The DA closes the case

The day after the crash, the Suffolk police department issued a news release about the crash, identifying Cavooris, the injured children and Mascarella. The release reported that Mascarella “self-transported to Southside Hospital in Bay Shore with minor injuries.” The department did not identify him as a member of the force.

Officers Antola and Greene amended the reports they wrote hours after the crash, adding that they saw no evidence that Mascarella had been drinking.

Antola also changed his report to state that he had recognized Mascarella on sight, not that Mascarella had introduced himself.

Cutrone amended his DMV accident report to state that Mascarella had said “he briefly looked down towards his radio” before the crash. Cutrone then amended the report a second time, deleting his account that Mascarella said he looked at the radio. Instead, he again cited only “driver inattention/distraction.”

Det. Ellis took a sworn statement from Cavooris that described the impact of the crash and the events that followed.

The records included no statement by Mascarella.

The district attorney’s office and police internal affairs opened their investigations — while lacking the results of breath or blood testing that would have determined whether Mascarella had consumed alcohol.

“Clearly not having a breath test makes bringing a DWI case much more difficult. This difficulty is compounded when an arrest is not made at the time of the incident,” Griffin wrote.

Bandler noted both that Mascarella had not been tested and that officers reported they saw no signs of intoxication. The officers included Antola, Greene, Wustenhoff, McQuade and Fisher, who noted glassiness in Mascarella’s eyes.

“The case has a lot of problems,” he said. “You have police who failed to perform certain steps and record certain responses, police who have put in their reports they observed no signs of intoxication. I think they would not be able to prove beyond a reasonable doubt in court that he was intoxicated.”

Suffolk County Assistant District Attorney Carl Borelli, who worked on major vehicle accidents, subpoenaed Mascarella’s phone records, according to police statements, apparently trying to determine whether Mascarella was using a phone at the time of the crash. The police documents did not include the results of the subpoenas.

The chief of detectives took the investigation away from Fourth Precinct detectives.

There was “no evidence of criminality to date,” Ellis wrote nine days after the crash.

Major Case Unit detectives contacted Cavooris. He and Valerie learned for the first time that an off-duty officer had been at the wheel of the Ram. They had known that the Ram’s driver had refused a breath test and had accepted that police still judged that the driver was sober.

Valerie said discovering that the driver was a police officer “completely shifted my entire narrative of the situation. And I felt like I had to reprocess everything all over again.”

‘If he was not impaired, then why would he refuse?’

Valerie Cavooris“If he was not impaired, then why would he refuse? But I trusted that the officers could tell what was happening,” she said. “They’re trained to know who’s impaired and who’s not. So, I just took it at face value.”

Armed with a warrant, detectives searched the Ram at the county’s impound garage. They collected samples of liquids from water bottles and a Yeti tumbler. The police documents did not include results of tests performed on the liquids.

The DA summoned four police officers who responded to the crash for questioning about what they observed when they interacted with Mascarella. PBA attorney Alex Kaminski accompanied each officer during his interview.

The “interviews yielded no new information,” and the investigation was closed, Det. Sgt. James McGuinness wrote in a report.

In January, Raymond Tierney succeeded Sini as district attorney. In June, his office stated that prosecutors were continuing to look at the circumstances of the crash.

“This matter is currently under investigation,” an aide to Tierney wrote in rejecting a Freedom of Information Law request for access to records submitted by Newsday.

Cavooris and Valerie have moved from Long Island to Massachusetts, where Kevin got a job as a data analyst. Valerie, who works in marketing for a nonprofit, is pregnant with their third child. The crash still shadows their lives. They are seeking an insurance settlement through Mascarella’s insurance carrier. They have not filed a lawsuit. They wonder whether Riordan will ever walk or move without limitation, and whether brain damage will more deeply affect his future.

“Riordan is such an amazing, happy, active, energetic, playful, silly, curious kid. He doesn’t know what he went through. But one day he will, and one day he’ll be asking for answers,” Cavooris said. “All we can do as parents is try to have as many answers for him when that day comes.”

MORE COVERAGE

Reporter: David M. Schwartz

Editors: Arthur Browne, Keith Herbert

Photos: Jeffrey Basinger, Alejandra Villa-Loarca, Reece T. Williams, Chris Ware

Senior multimedia producer: Jeffrey Basinger

Video editors: Jeffrey Basinger, Greg Inserillo

Script production: Arthur Mochi Jr.

Photo editor: John Keating

Project management: Heather Doyle, Joe Diglio, Erin Serpico

Digital design/UX: James Stewart

Social media editor: Gabriella Vukelić

Print design: Jessica Asbury

QA: Sumeet Kaur