For many years, Grumman, the Bethpage aerospace giant, knew its toxic chemicals were contaminating area groundwater, but kept critical information from the public as it avoided culpability and many cleanup costs, a Newsday investigation has found.

This behavior, newly revealed in confidential company documents, was long enabled by regulators who downplayed the pollution and did little to contain its spread from Grumman’s facility to the larger community and, now, to neighboring towns.

At 4.3 miles-long, 2.1-miles-wide and as much as 900-feet deep, the plume is among the most complex and significant of its kind nationwide. An agglomeration of two dozen contaminants, it includes multiple carcinogens, most significantly the potent metal degreaser trichloroethylene, or TCE, which is in pre-treated water at levels thousands of times above state drinking standards.

The solvent most infamously poisoned the water supply in Woburn, Mass., in the 1980s, causing a childhood leukemia cluster and prompting the successful litigation depicted in the book and film, “A Civil Action.”

Grumman relied on TCE to clean aircraft parts for 40 years, but at its peak obscured or outright denied its use. The company released so much of the chemical into the ground that its own environmental manager later wrote to a colleague that the thought “caused my insides to start churnin’ somethin’ fierce!!”

Public water providers in and around Bethpage have spent more than $80 million to cleanse their water within the plume. They cite consistent sampling that shows what’s delivered to taps meets all state and federal drinking standards, but wary consumers still clear bottled water from supermarket shelves, especially as other potential health risks, such as radium and the industrial stabilizer 1,4-dioxane, a likely carcinogen, are identified.

Email between environmental manager and colleague

From: Smith, Kent A.

Sent: March 15, 2011

To: Cofman, John

Subject: RE: How Much TCE Spilled? Perspective

Perspective? How’s this for perspective? The fact that there might have been a total release of 40,000 gallons of TCE just caused my insides to start churnin’ somethin’ fierce!!

Man, oh man, that’s a lot of material

From: Cofman, John

Sent: March 16, 2011

To: Smith, Kent A (AS)

Subject: RE: How Much TCE Spilled? Perspective

Yes — I was stunned when looking at this.

Read the emailsThe nine-month Newsday investigation, built on thousands of pages of records and scores of interviews, found numerous points over the last 45 years that the pollution from Grumman could have been addressed more aggressively. But instead of candor and decisiveness, obfuscation, and foot dragging took hold – not only by Grumman, but also at first by Nassau County and, until recently, the state Department of Environmental Conservation, the lead regulatory agency.

The consequences have been measurable.

When the county in 1986 first identified the migrating contaminants as a plume, it was two-miles long, one-mile-wide, up to 500-feet deep and yet to cross Hempstead Turnpike. In doubling in size, it has crossed the Southern State Parkway and moves, a foot per day, toward the Great South Bay, the centerpiece of Long Island’s estuaries.

After years of inaction, the state has approved a $585 million plan to finally fully contain and remediate the plume, with Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo saying it will fall to the polluters to do the work or face litigation aimed at recovering the costs. If that fails, the state would pay for the project itself.

The Grumman emblem on a tank on top of Plant 5 at the Grumman Corp.s Bethpage facility on March 9, 1966. Photo credit: Newsday / Dick Kraus

Under New York’s “Superfund” program, Grumman, now Northrop Grumman, shares cleanup responsibility with the U.S. Navy, owner of a sixth of the once-600-plus-acre Bethpage complex.

What Grumman knew

Beyond the fact that Grumman fully operated the site, its behavior stands out from the Navy’s because of how it contrasts with the corporation’s paternal presence in the era when it was Long Island’s economic engine. It employed more than 20,000 people and was revered for building World War II fighters and the space module that took Neil Armstrong to the moon.

Before its 1994 acquisition by Northrop Corp. greatly diminished its jobs and presence in the community, Grumman all but defined Bethpage. One French restaurant got so much business from company executives it was dubbed “Grumman’s annex.” Schools would stagger dismissals to avoid the traffic crush from the plants’ day shift letting out.

Northrop Grumman now holds nine acres, and employs about 500 people, in Bethpage.

Grumman’s own documents, and its admissions… are clear that its long-term, historical practices created contamination.

U.S. District Court Judge Katherine B. Forrest

Many of the starkest examples of what Grumman knew about the pollution it caused, but did not share publicly, were found in a series of exhibits and decisions in sparsely-covered federal lawsuits filed in 2012 and 2016. Grumman’s primary insurer during the 1970s and ‘80s, The Travelers Companies, argued successfully that it has no duty to cover potential liabilities for the company’s past practices in part because Grumman had not provided it with full or timely notice about its role in the pollution.

In 2014, U.S. District Court Judge Katherine B. Forrest wrote, “Grumman’s own documents, and its admissions in reply to Travelers’ [motion] are clear that its long-term, historical practices created contamination.”

Last year 2019, Judge Lorna G. Schofield separately ruled: “no reasonable jury could conclude,” even in the ‘70s, that “Grumman lacked sufficient information” to know its pollution could open it to damages.

Grumman’s own documents, and its admissions… are clear that its long-term, historical practices created contamination.During the first case, telling documents emerged that were never meant to be seen. Nearly every exhibit submitted by Northrop Grumman and Travelers was filed under seal, as were those submitted by another party, Century Indemnity Company, a successor to Grumman’s insurer during the 1950s and 1960s.

But Newsday discovered that 23 of the 42 exhibits Century offered in support of one critical motion — all marked “confidential” – had not been sealed as intended and were available on a court records website with the notation “FILING ERROR – DEFICIENT DOCKET ENTRY.”

Together with historical news articles and decades of official correspondence received by Newsday under state and federal Freedom of Information laws, the secret documents reveal what the company knew, when it knew it, and what was withheld from the public.

“…we have no evidence of any risk to the environment.”

Newsday Grumman hazardous site and denial Seel full document

“A shallow…plume of organic contamination consisting of volatile organic compounds was documented beneath the Grumman facility…”

DEC reclassification report on Grumman site Seel full documentAs early as 1955, for example, the state determined that Grumman’s toxic wastes, then identified as chromium and other heavy metals, could “concentrate as slugs or ribbons which might eventually contaminate the water in public supply wells at a considerable distance.”

In 1976, Grumman’s environmental consultant concluded in a private memo that “basins, lagoons, spills, etc. have created a slug of contaminated ground water in the shallow aquifer underlying at least part of the plant.”

Through it all, Grumman insisted that it had no knowledge it was the source of much of the underground mass. It maintained the public position into the 1990s, even as it continued receiving similar information, internally and from government agencies.

The company also allowed regulators to create a false narrative that a nearby manufacturer – responsible for another toxic chemical found at lower levels – was the primary cause of its pollutants. It would take decades to undo that perception.

Grumman planes on display at the Grumman annual company picnic in an undated photo. Printed in Newsday on March 13, 1994. Photo credit: Stan Wolfson

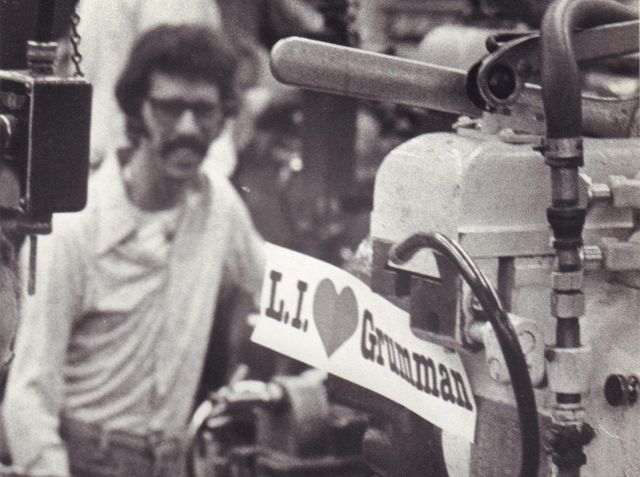

An “L.I. Loves Grumman” sticker is shown on a machine in the milling area of Grumman’s Bethpage facility on Nov. 13, 1981. Photo credit: Newsday/Daniel Goodrich

In her 2014 decision, Forrest discredited Northrop Grumman’s argument that Grumman initially thought it wasn’t to blame, writing: “a belief in non-liability was unreasonable based on the factual record.”

‘Complete and utter failure’

More recently the company, with the state’s help, moved from denial to persistently minimizing the problem and dodging costs.

In the 1990s, a Northrop Grumman consultant developed a computer model used by the state that grossly underestimated how the plume would grow. Notably, it predicted that the toxic contamination wouldn’t spread to additional public water supply wells beyond Bethpage in the next 30 years. Within a decade wells that serve South Farmingdale, Levittown and North Wantagh were hit.

It also predicted that, through treatment and natural processes, a TCE-contaminated well in Bethpage would be cleaned to state drinking water standards of 5 parts per billion by 2012. The average TCE concentration was 83 parts per billion in 2012 and 349 last year 2019.

Until the federal government intervened and put its use to a halt, the state relied on that faulty model to issue limited, less-expensive cleanup plans that failed to contain the plume.

It illustrated that it often acted as Grumman’s ally in minimizing the extent of the pollution and what was needed to fight it.

At the start of the cleanup, in 1990, the it dismissed calls to tackle the off-site groundwater pollution, saying it “would be a waste of time and money.”

“…we have no evidence of any risk to the environment.”

Newsday Grumman hazardous site and denial Seel full documentPositions like that, compounded over time, have helped Virginia-based Northrop Grumman avoid numerous costs for cleaning the region’s contaminated water and soil. Many were instead borne by local taxpayers.

“Everyone involved should be ashamed to admit that this plume has been known about since the 1970s, and 40 years later, it is bigger, deeper and worse than ever,” district superintendent Michael Boufis told state lawmakers at a 2016 hearing. “A complete and utter failure of the system.”

Hundreds of millions spent

Northrop Grumman declined multiple requests for sit-down interviews.

In written statements, the company and the Navy each highlighted a range of cleanup measures they’ve engaged in over the last 30 years, which they claim have cost about $300 million combined.

Tim Paynter, a Northrop Grumman spokesman, wrote, “For over two decades of environmental remediation efforts in Bethpage, Northrop Grumman has worked closely and extensively with New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the United States Navy, the New York State Department of Health, and other federal, state and local regulatory authorities to develop and implement scientifically sound remediation strategies that protect human health and the environment. Northrop Grumman’s commitment to remediation in Bethpage is an important aspect of its ongoing legacy.”

The company has repeatedly defended its waste disposal practices as legal at the time, although the Superund process holds polluters responsible for costs nonetheless. In terms of clean-up, it touts, in particular, a long-running containment well system along the boundary of Grumman’s former property that has extracted nearly 200,000 pounds of groundwater contaminants.

“We cut off that offsite migration,” Ed Hannon, a Northrop Grumman project manager, told residents at a January 2020 public hearing.

But approximately 200,000 more pounds of toxic chemicals still await removal beyond the original grounds, according to the state. After a decade of planning and construction, the company is still completing its first comprehensive off-site system to remove plume contaminants before they reach drinking wells, joining one that the Navy operates and another it is planning.

Northrop Grumman said it has spent $200 million on the plume, but unlike the Navy, refused to break down that cost. Critics contend it is inflated by payments to lawyers and consultants that have helped it stall and avoid cleanup responsibility.

The Navy since 1995 has contributed more than $40 million to public water supply treatments in Bethpage, Levittown and South Farmingdale, compared to about $3.6 million paid by Grumman/Northrop Grumman.

“The Navy is focused on fulfilling its responsibility to protect human health and the environment, and we take our role in these clean-up efforts seriously,” a Navy spokesman, J.C. Kreidel, said in a statement when asked about the difference in contributions.

Northrop Grumman cites these existing treatments – specifically officials’ reassurances that they make the area’s drinking water safe – to argue that a more extensive cleanup is unnecessary. Water providers call that argument specious because it leaves the burden to them and their ratepayers. Environmentalists also note that it’s unknown how the various contaminants in the toxic mix react with each other, what new ones will emerge, such as the likely carcinogen 1,4-dioxane that can’t be removed by traditional treatment, and what happens when all of this hits the Great South Bay.

The ire in the community continues unabated, and a review of Grumman’s legacy over more than 50 years shows why.

In the early 1960s the company donated 18 acres of land to the Town of Oyster Bay for what became Bethpage Community Park. It had used several acres of it as a dump site for toxic sludge and solvent-soaked rags. In 2002, seven years after the state had dismissed the park as a pollution concern, it was closed because of soil contamination.

The park’s ballfield, built directly over the rag pit, remains closed.

But the problem turned out to be worse than just soil. In 2007, the Bethpage Water District found that the park – specifically the ballfield – was also the source of the highest levels yet detected of TCE-tainted groundwater.

It asked Northrop Grumman to pay it millions of dollars for upgraded treatment and wound up in protracted negotiations. When the district finally sued the company in 2013, the case was tossed because it had missed the three-year legal window to bring a claim.

Bethpage residents, who are increasingly joining class action lawsuits, have become consumed by suspicions that the cancers afflicting their family members, neighbors and themselves can be traced to the pollution, despite a lack of conclusive studies.

Property values around town are also of such concern that realtors sometimes call the water district superintendent to open houses to assure prospective buyers of the water’s safety.

Pamela Carlucci, 68, a cancer survivor who has lived in Bethpage for 43 years, encapsulated the feelings that many in her community have of the polluters, regulators and water providers alike: “Should we trust them?”

Moments of consequence

The story of the pollution plaguing Bethpage is marked by many failures, but underpinning them all is that the public wasn’t told the truth when the problem was first emerging.

That left tens of thousands of people in the dark about something that deeply affected their lives and to this day has created widespread distrust.

Below are five of the most telling examples of this deceit, all from the documents meant to be kept secret and discovered during the Newsday investigation.

They have been culled from “The Making of an Environmental Disaster,” which will appear tomorrow and presents the full, seven-decade narrative of how the contamination came to be and grow to such avoidable proportions.

As much as they reveal on their own, these examples stand out even more in the context of that chronicle.

1. ‘CONTAMINATION MAY SPREAD’

In June 1976, Grumman’s environmental consultants, Geraghty & Miller, presented the company with the confidential memo that identified pollution problems as caused by the plant’s “basins, lagoons, spills, etc.”

But just as significantly, it predicted, in prescient terms, that the groundwater contamination, which had already shut several of Grumman’s private drinking water wells, “may spread both laterally and vertically beneath the property;” that “neighboring wells may become contaminated over the long term;” and that “further contamination may take place from sources presently not detected.”

“If they had done their job in ’76, when they knew about the polluted wells, we wouldn’t be here today,” said John Sullivan, chairman of Bethpage Water District’s board of commissioners.

Grumman didn’t tell employees or the public of these findings. The problem would only surface a half-year later because an alarmed state official with access to Bethpage water sampling results called an Albany newspaper.

2. ‘I’D DRINK THE WATER’

On Dec. 2, 1976, the Bethpage Water District shut down the first of its public supply wells because of TCE contamination of 60 parts per billion, above the state standard of 50 that would be set in 1977 – and 12 times today’s of 5. County Health Commissioner John Dowling told Newsday, “If I lived in the area, I would continue to drink the water. We don’t have any information that the chemicals are harmful in drinking water.”

That same day Dowling had been present for an ominous private warning about the water. He was among the officials who met with Grumman representatives, according to a memo that was among the meant-to-be-sealed Century Insurance documents. The memo included confidential handwritten notes to Grumman by Geraghty & Miller that recorded a sharp disagreement between the federal Environmental Protection Agency and a representative of the state Department of Environmental Conservation:

EPA — “Don’t drink the water”

State [illegible] disagrees

EPA — “no basis for levels that are acceptable”

It is unclear how Dowling, who is deceased, could have made his public comment– but no one else in the room alerted the public to those federal concerns, which came on top of the National Cancer Institute reporting that TCE had caused cancer in mice and federal officials moving to limit workplace TCE exposure.

It was only last year, that state officials suggested that levels of TCE in Bethpage public water before late 1976 were high enough to harm people’s health.

3. ANOTHER COMPANY TAKES THE FALL

Faced with the contamination, Nassau and state officials placed almost all the blame at the feet of Hicksville’s Hooker Chemical Company, which operated at a far-smaller site adjacent to Grumman’s western edge.

Privately, the Bethpage Water District had evidence this wasn’t the case and blamed Grumman. In November 1977, it sent the company a letter demanding damages and asserting, “currently available evidence indicates that…contamination has arisen by virtue of discharge of waste products from your company into the ground water supply,” according to Judge Forrest’s insurance case ruling.

But the district never publicized its position.

Instead, a few years later, it blamed only Hooker, with the district’s lawyer at the time telling a Bethpage newspaper that he was sharing, for the first time, “district records of its two-year struggle to force Hooker to pay up to one million dollars for replacement costs” of the TCE-tainted well.

The small water district then had such a collegial relationship with the powerhouse company based in its town that it often preferred to cut deals in private, sometimes over beers.

“It was Grumman and the district coming in and sitting down at a table,” said Richard Humann, a longtime Bethpage Water environmental consultant. “It was ‘What do we need to do?’ ‘Ok, you did this, we’re going to do this, you’re going to do pay this.’ Then they’d shake hands, go out, and it was done.”

4. CHERRY PICKED-DATA

In 1978, Geraghty & Miller privately presented Grumman with results from a 3-day sampling of its industrial wastewaters, in which it attributed the results to company “housekeeping practices” such as spills and equipment cleanup. At 4 p.m., a peak usage time, the samples showed an average of 17 lbs. per day of TCE, according to the confidential report, which was also mistakenly left unsealed.

But when the company published the data few years later as part of a presentation highlighting its concern for the environment, it omitted the 17-pound reading, which was enough to contaminate 292 million gallons of groundwater, according to a court filing by the Century company.

Grumman only presented measures from midnight, 4 a.m. and 8 a.m. two days later that showed an average of between 2 and 6 lbs. per day of TCE in the water.

Included in the presentation was a statement from a Grumman executive that read, “The concerns of Long Island are the concerns of the 20,000 Grummanites who live and work here.”

5. ‘NO QUESTION REGARDING LIABILITY’

Grumman executives, lawyers and insurers huddled in August 1989 to discuss a complaint from the Bethpage Water District, which had privately notified the company that a second of its public wells had been polluted with TCE.

In another memo that was meant to be sealed, a company summary of the meeting offered this blunt summary: “Data is conclusive that it is Grumman plume which is contaminating the [Bethpage] Water Districts [sic] well.” It underscored the point: “No question regarding liability as there are no other direct parties [that] appear to have contributed to contamination yet.”

Yet in March 1990, some of the same Grumman officials present at the 1989 meeting were interviewed by the town’s weekly newspaper, The Bethpage Tribune, for an article headlined, “Rumors of Grumman Contamination Pose No Threat.”

The story, filled with reassuring comments from the executives, included this line: “Grumman doesn’t admit liability on the issue of contaminating Bethpage wells.”

1966

September

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

November

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

June

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

July

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

1968

September

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

November

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

1970

September

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

November

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.