Grumman, the Bethpage aerospace giant, knew as far back as the mid-1970s that its toxic chemicals were contaminating area groundwater, but it kept secret crucial information that could have helped stop what is now Long Island’s most intractable environmental crisis, a Newsday investigation found.

On numerous occasions, particularly during a critical 15-year period, the company made public statements that directly contradicted the alarming evidence it held, as it avoided culpability and millions in costs.

This behavior was long enabled by government officials who downplayed the pollution and did little to contain its spread from Grumman’s once-600-acre site, through Bethpage and into neighboring communities.

The nine-month Newsday investigation, built on thousands of pages of records and scores of interviews, charts a largely hidden history, one that emerges, most strikingly, in confidential Grumman and government documents revealed for the first time.

They show that the problem could have been addressed more aggressively at many points over the past 45 years. But instead, foot-dragging, resistance and grossly inaccurate projections took hold — not only on the part of the company but also for decades by the state Department of Environmental Conservation, the lead regulatory agency.

The U.S. Navy, which owned a sixth of the Grumman-operated facility, has also often objected to the costliest, most-comprehensive cleanup plans.

Though 4.3 miles long, 2.1 miles wide and as much as 900 feet deep, the plume’s significance is defined by more than size. Unlike most similar masses, it sits in an aquifer that is the only drinking water source for a densely populated region.

As one of the most complex in the nation, it is composed of two dozen contaminants, including multiple carcinogens. Most significant is the potent metal degreaser trichloroethylene, or TCE, which is present in pretreated water at levels thousands of times above state drinking standards.

Grumman relied on TCE to clean aircraft parts for 40 years, but as the chemical was discovered to be spreading from its property, it obscured or outright denied its use. The company released so much of it into the earth that one of its environmental managers later wrote to a colleague, in a newly revealed email, that the thought “caused my insides to start churnin’ somethin’ fierce!!”

A growing number of expensive treatment systems remove TCE and other contaminants from public wells within the plume, including ones serving not only Bethpage, but Plainedge, South Farmingdale, North Massapequa and parts of Levittown, Seaford, Wantagh and Massapequa Park. State and local authorities consistently certify the treated drinking water as safe, but cases of bottled water fly off supermarket shelves and residents’ health concerns, particularly about cancer, are numerous.

The pollution that originated from Grumman is classified as a “significant threat to public health or the environment” under the state’s Superfund program, which aims to clean hazardous waste sites.

“Everyone involved should be ashamed to admit that this plume has been known about since the 1970s, and 40 years later, it is bigger, deeper and worse than ever,” Michael Boufis, superintendent of the Bethpage Water District, told state lawmakers at a 2016 hearing. “A complete and utter failure of the system.”

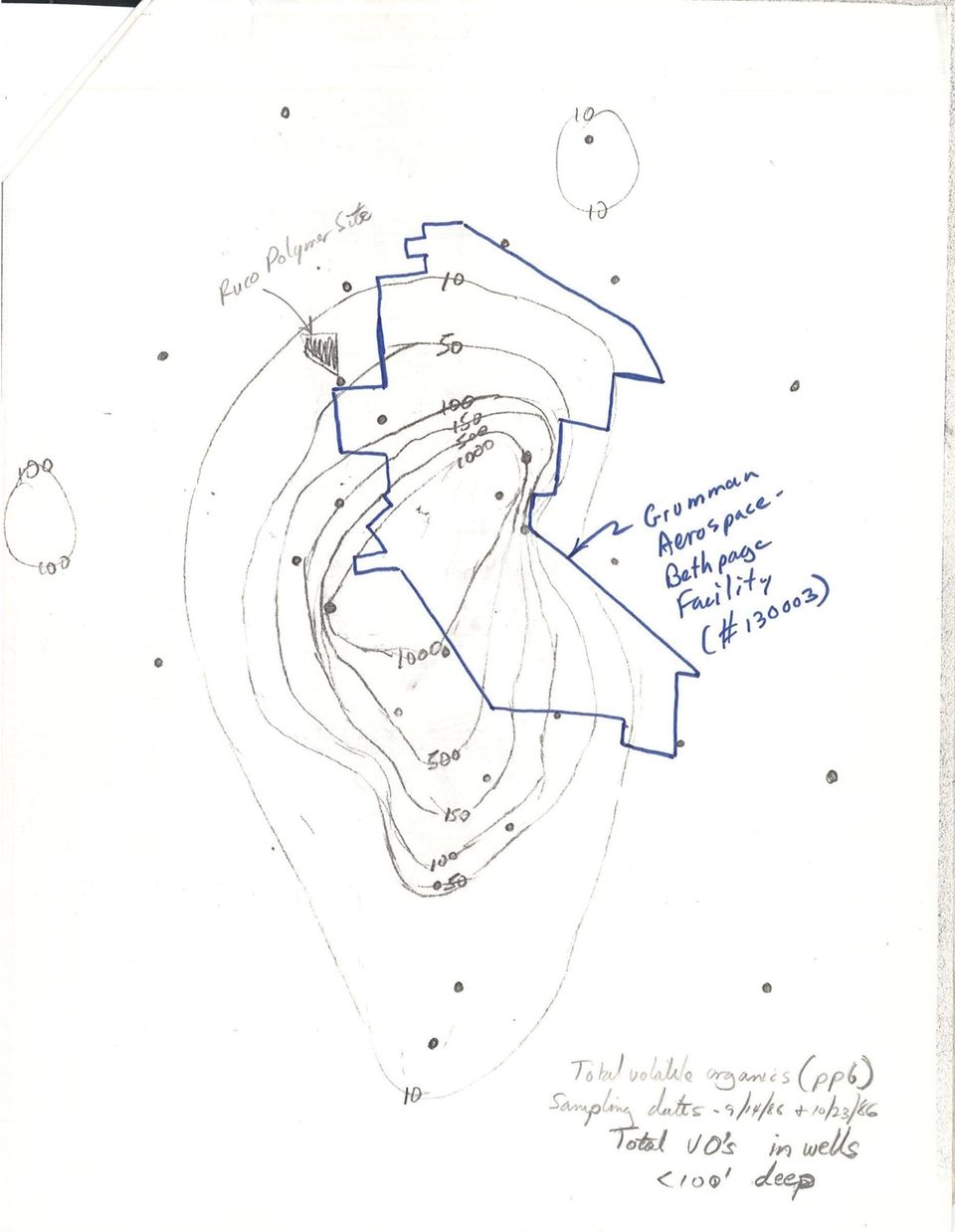

When Nassau County and the U.S. Geological Survey in 1986 first identified the migrating contaminants as a plume, it was two miles long, one mile wide, up to 500 feet deep and yet to cross Hempstead Turnpike. In doubling in size, it has crossed the Southern State Parkway and moves, at a foot a day, toward the Great South Bay, the centerpiece of Long Island’s estuaries.

The first known visualization of the plume, included in a 1987 state report. Source: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

Local taxpayers have paid more than $50 million for a portion of the public water treatments and a seven-acre soil cleanup by the Town of Oyster Bay, of which Bethpage is a part. The Navy, which is also responsible for remediation under the Superfund decisions, says it has spent more than $130 million in total, including for some of the public treatments.

Grumman’s successor, Northrop Grumman, says it has spent $200 million, but unlike the Navy it has declined to break down those costs. Critics question whether that figure includes payments to lawyers and consultants, but the company has completed a substantial system of groundwater contaminant extraction wells along its former properties.

How much more will it cost to contain and eliminate the plume?

The state’s comprehensive plan, announced last year, estimates it will take $585 million over the first 30 years alone. Near-total eradication of the contamination wouldn’t come for 110 years.

The plan is a remarkable reversal of the state’s far more cautious approach in decades past. It wants Northrop Grumman and the Navy to fund it or face litigation.

What Grumman knew

Grumman’s role in the crisis contrasts with its paternal community presence in the era when it was Long Island’s economic engine. It employed more than 20,000 people and was revered for building World War II fighters and the space module that landed Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon.

Before its 1994 acquisition by Northrop Corp. greatly diminished its jobs and presence, Grumman all but defined Bethpage. One French restaurant got so much business from its executives it was dubbed “Grumman’s annex.” Schools would stagger dismissals to avoid the traffic crush from the plants’ day shift letting out.

Virginia-based Northrop Grumman now occupies nine acres in Bethpage, employing about 500 people. Corporate offices, distribution centers and a movie soundstage fill the rest of the old site.

Everyone involved should be ashamed to admit that this plume has been known about since the 1970s, and 40 years later, it is bigger, deeper and worse than ever.

Michael Boufis, superintendent of the Bethpage Water District

“A lot of people had a lot of pride working for Grumman,” said Jeanne O’Connor, 49, a fourth-generation Bethpage resident and activist for a stronger cleanup whose mother and grandfather held jobs there. “Now it feels like that image has been severely tainted by the fact that they left this mess.”

Many of the starkest examples of Grumman’s private knowledge were found in a series of exhibits and decisions in sparsely covered federal lawsuits filed in 2012 and 2016. Grumman’s insurer during the 1970s and ’80s, The Travelers Cos., successfully argued that it had no duty to cover liabilities for the company’s past practices in part because Grumman had not provided it with full or timely notice about its role in the pollution.

In her 2014 decision, U.S. District Court Judge Katherine B. Forrest wrote, “Grumman’s own documents, and its admissions in reply to Travelers’ [assertions] are clear that its long-term, historical practices created contamination.”

She rattled off a number of pollution-causing practices that “Grumman knew” of in the period it publicly denied responsibility. They included using TCE in degreasing vats and spray guns, discharging TCE-contaminated water into basins that allowed it to leach into the ground, placing TCE-laden wastewaters in unlined “sludge drying beds” dug into the dirt and using a 4,000-gallon TCE storage tank that it was aware was leaking.

Workers construct a Grumman G-21 Goose amphibious aircraft on the Bethpage production line in an undated photo. Credit: Grumman History Center

In a separate ruling last year, a second district court judge, Lorna G. Schofield, pinpointed when Grumman, through consultant and regulator warnings, should have known its liability: “No reasonable jury could conclude that in June 1976, Grumman lacked sufficient information” to reasonably know its pollution could leave it on the hook for damages.

The first case contained unintended revelations, as telling documents emerged that were never meant to be seen.

Nearly every exhibit submitted by Northrop Grumman and Travelers was filed under seal, meaning they were to be kept from public view, as were those submitted by another party, Century Indemnity, a successor company to Grumman’s insurer during the 1950s and 1960s.

But Newsday discovered that 20 of the 39 exhibits Century offered in support of one motion — all marked “confidential” — had not been sealed as intended and were available on a court records website with the notation “FILING ERROR — DEFICIENT DOCKET ENTRY.”

Together with historical news articles and decades of official correspondence Newsday obtained under state and federal Freedom of Information laws, the secret documents reveal what the company and regulators knew, when they knew it and what was withheld from the public.

The court records mistakenly left unshielded contain prophetic governmental concerns about Grumman’s toxic wastes going back to the 1950s, profound warnings from a company consultant in the ’70s and a confidential summary of a 1989 meeting that declared Grumman’s unequivocal responsibility for pollution that had reached public drinking wells.

There is also urgent internal correspondence from a Northrop Grumman manager in 2000 alerting that the plume was spreading well beyond the contours predicted by company consultants.

Several documents detail how state and county officials for years falsely blamed the bulk of the pollution on a neighboring manufacturer. They clung to this position even though, as Grumman’s own consultants noted early on, at least one of its tainted wells was positioned north of the adjacent plant — in an area where groundwater contamination flowed south.

In her 2014 decision, Judge Forrest discredited Northrop Grumman’s argument that Grumman provided late notice to its insurer because it initially thought it wasn’t responsible, writing: “a belief in non-liability was unreasonable based on the factual record.”

From denial to dodging

Little in this trove of confidential documents has been known publicly, making their language and findings all the more extraordinary.

In 1955, for example, the Nassau County Health Department determined that Grumman’s toxic wastes, then believed to be limited to chromium and other heavy metals, could “concentrate as slugs or ribbons which might eventually contaminate the water in public supply wells at a considerable distance.”

That assessment, seven years after chromium first reached a public drinking water well beyond Grumman’s plant, is the earliest known forewarning that a plume could develop.

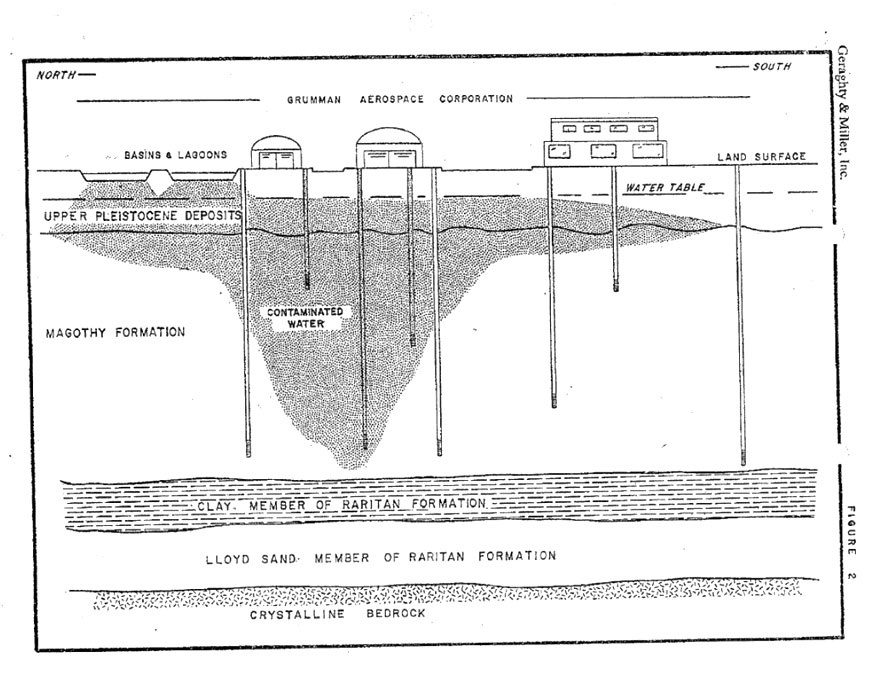

In June 1976 — after TCE had been found in a private Grumman well at a level 100 times today’s drinking water standard — the company’s environmental consultant concluded that “sources of contamination consisting of basins, lagoons, spills, etc. have created a slug of contaminated ground water in the shallow aquifer underlying at least part of the plant.”

A depiction of the groundwater contamination beneath Grumman, shown as part of a 1976 internal consultant memo to the company, shows the likely source as part of Grumman’s facility.

See full documentThat is the first known instance of contamination being identified by Grumman’s own experts as likely caused by its own practices.

Even after that, the company consistently stated that it was not to blame.

“A Grumman spokesman denied that the company’s own operations were responsible for the contamination,” Newsday reported in November 1976.

More recently, the company, with the state’s help, moved from denial to persistently minimizing the problem and dodging costs.

Beginning in 1990, the record becomes visible through voluminous Superfund documents, including long-overlooked technical reports and correspondence obtained through the public records requests. Among the most important threads that emerge is Northrop Grumman’s development of a computer model that substantially underestimated how much the plume would grow.

The modeling was particularly important because it was used by the state as a basis for developing limited, less-expensive cleanup plans that failed to stop the spread.

In 2000, it predicted that the toxic contamination wouldn’t reach public water supply wells beyond Bethpage in at least the next 30 years. Within a decade three additional wells required treatment.

A Bethpage well that it predicted would virtually be rid of TCE now treats contamination nearly 70 times the drinking water standard.

As it relied heavily on Grumman analyses like this, the state, at its most extreme, dismissed early calls to tackle the off-site groundwater pollution, remarking in 1990 that it “would be a waste of time and money.”

Basil Seggos, appointed the state’s environmental conservation commissioner in 2015, called the plume’s growth during the first quarter century of Superfund oversight “unacceptable.” The state in 2017 spent $6 million to conduct its own analysis, leading to a new model that informed the current $585 million cleanup plan.

“We’ve certainly put in place a much more aggressive and advanced and ambitious look into this,” he said in an interview.

200,000 pounds removed

Northrop Grumman declined multiple requests for sit-down interviews made between last June and earlier this month.

Tim Paynter, a Northrop Grumman spokesman, issued this statement: “For over two decades of environmental remediation efforts in Bethpage, Northrop Grumman has worked closely and extensively with New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the United States Navy, the New York State Department of Health, and other federal, state and local regulatory authorities to develop and implement scientifically sound remediation strategies that protect human health and the environment. Northrop Grumman’s commitment to remediation in Bethpage is an important aspect of its ongoing legacy; one which honors its exemplary service to the country since before World War II, during the space race, and today, as our Bethpage team continues to work on critical national security programs.

“Northrop Grumman remains committed to working with all stakeholders to provide for fact-based, scientifically-sound remediation efforts that advance the cleanup and help protect the community without unnecessary disruption and potential harm.”

The company has repeatedly defended its waste disposal practices as legal at the time, although the Superfund process holds polluters responsible for costs nonetheless.

In terms of cleanup, Northrop Grumman especially touts its system of five containment wells along the southern boundary of the old 600-acre property. The state estimates it has extracted nearly 200,000 pounds, or 18,000 gallons, of groundwater contaminants in the more than two decades it has operated.

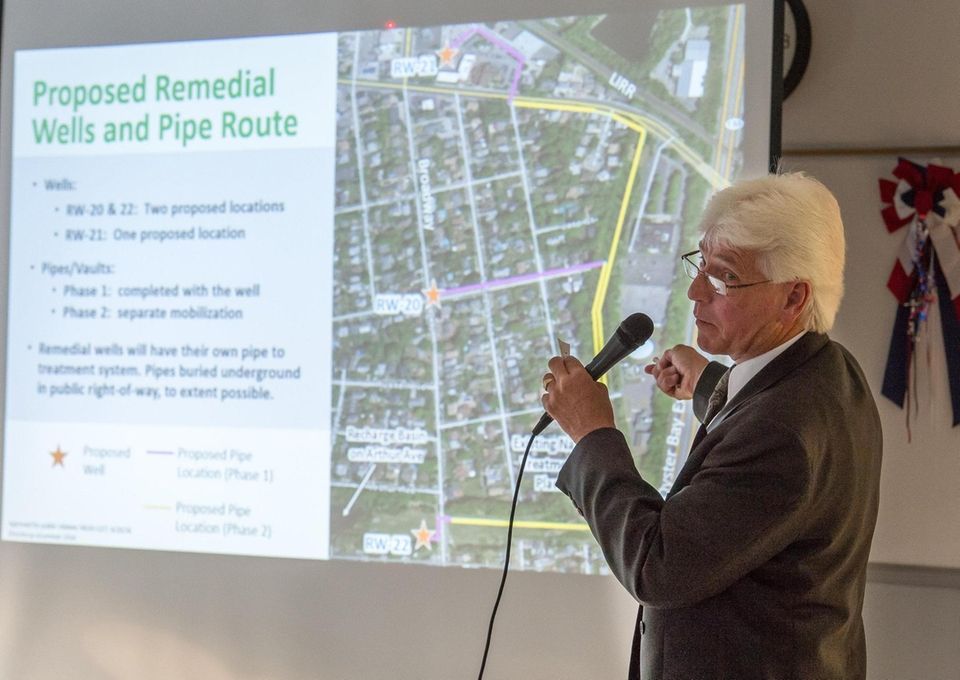

“We cut off that offsite migration,” Ed Hannon, a Northrop Grumman project manager, told residents at a January public hearing.

Ed Hannon, a Northrop Grumman project manager, explains cleanup efforts during a June 2016 meeting in Bethpage. Photo credit: Newsday / Daniel Goodrich

But approximately 200,000 more pounds of TCE still await removal, according to the state. After seven years of planning and construction, the company is still completing its first comprehensive off-site system of wells to remove plume contaminants before they reach drinking supplies, joining one that the Navy operates and another it is planning.

The Navy since 1995 has contributed more than $45 million for five public water supply treatments installed by the Bethpage and South Farmingdale water districts and New York American Water, which serves thousands of customers nearby. Northrop Grumman, in comparison, has paid about $5.4 million in construction and maintenance costs for the first two systems built by Bethpage in the early 1990s, according to a company attorney’s demand to Travelers for coverage.

“The Navy is focused on fulfilling its responsibility to protect human health and the environment, and we take our role in these cleanup efforts seriously,” a Navy spokesman, J.C. Kreidel, said in a statement when asked about the difference in public treatment contributions.

Northrop Grumman has cited these existing treatments — and the reassurances from government officials that they make the area’s drinking water safe — to argue that a more extensive cleanup is unnecessary. Water providers say that argument unfairly leaves the burden of continued monitoring and expense on them and their ratepayers — not on the polluters.

Experts also note that it’s unknown how the various contaminants in the toxic mix react with each other, what new ones — like the solvent stabilizer 1,4-dioxane, a likely carcinogen — will emerge that can’t be removed by traditional treatment and what happens if all of this hits the Great South Bay.

‘Should we trust them?’

As recently as last summer, local officials publicly celebrated Grumman on the 50th anniversary of the moon landing. But some actions by the company and its successor are serving to break those strong bonds of community pride, residents say.

Northrop Grumman went to court successfully to fight paying more than $30 million in remediation and treatment costs borne by taxpayers. Newly discovered records show that Grumman once presented the public with cherry-picked data to paint a misleading picture of how much TCE it was putting into the ground.

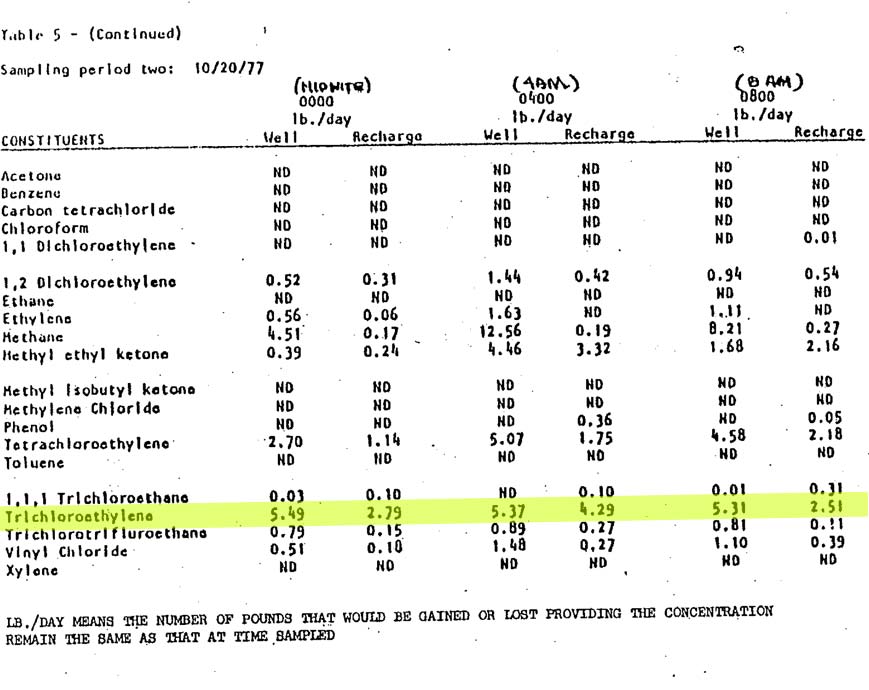

When presenting wastewater sampling to the public in 1982, Grumman highlighted a page from a previous consultant report that showed moderate levels of TCE being pumped from and put back into the ground at off-peak plant hours.

See full document

Grumman didn’t include the previous page from the same 1978 consultant report, showing one eye-popping TCE figure from a peak plant operation time. The company later called the reading an anomaly.

See full pageAnd its donation of land to the Town of Oyster Bay turned into an environmental debacle.

The 18 acres, gifted in the early ’60s, led to creation of Bethpage Community Park, a multigenerational centerpiece with a swimming pool, ice skating rink and ballfield.

It turned out that the gift included what had been a dumpsite for Grumman’s toxic wastewater sludge and solvent soaked rags, a fact undisclosed to the public for 40 years.

In 2002, less than a decade after the state had summarily ruled out the park as a pollution concern, it was shut down because the soil was found to contain elevated levels of two carcinogens, the industrial compound polychlorinated biphenyl, or PCB, and chromium.

Most of the facility reopened within a year, but the park’s ballfield, built directly over the three-plus acres that Grumman had once called an “open pit” for its wastes, remains closed.

In 2007, the Bethpage Water District discovered that the ballfield also was the source of some of the highest levels yet detected of TCE-tainted groundwater — several thousand parts per billion. The state would soon confirm it as a second plume, now commingled with the original mass from the Grumman plant.

The park saga is one of the better-known components of the Grumman pollution story. But the Newsday investigation has uncovered documents showing that the town knew from the start how the site had been used — though it believed the wastes were nontoxic. Once it became clear that its contamination had spawned another plume, Northrop Grumman consultants tried to obscure the detailed history of site dumping that another consultant had previously written.

Today, Bethpage residents are increasingly joining class action and personal injury lawsuits over the decades of contamination, mostly against Northrop Grumman but also against Oyster Bay. Many in the community have become consumed by suspicions that the cancers afflicting their family members, neighbors and themselves can be traced to the pollution, despite a lack of conclusive proof.

Longtime Bethpage resident Pamela Carlucci, 68, a breast cancer survivor, lost a son to brain cancer at age 30 in 2007. Photo credit: Johnny Milano

Pamela Carlucci, 68, a cancer survivor who has lived in Bethpage for 43 years, encapsulated the feelings that many in her community have of the polluters, regulators and even the water providers who have battled for a stronger plume offensive.

“Should we trust them?”

Moments of consequence

Underlying many of the missteps that forestalled a comprehensive cleanup was a failure to tell the public the truth when the problem was first emerging.

Below are a few of the numerous examples of private knowledge kept secret, some of it further shrouded by public statements to the contrary.

They have been culled from an extensive four-part history of how the contamination came to be — and how it grew. As much as they reveal on their own, these examples stand out even more in the context detailed in that chronicle of failure.

1. ‘CONTAMINATION MAY SPREAD’

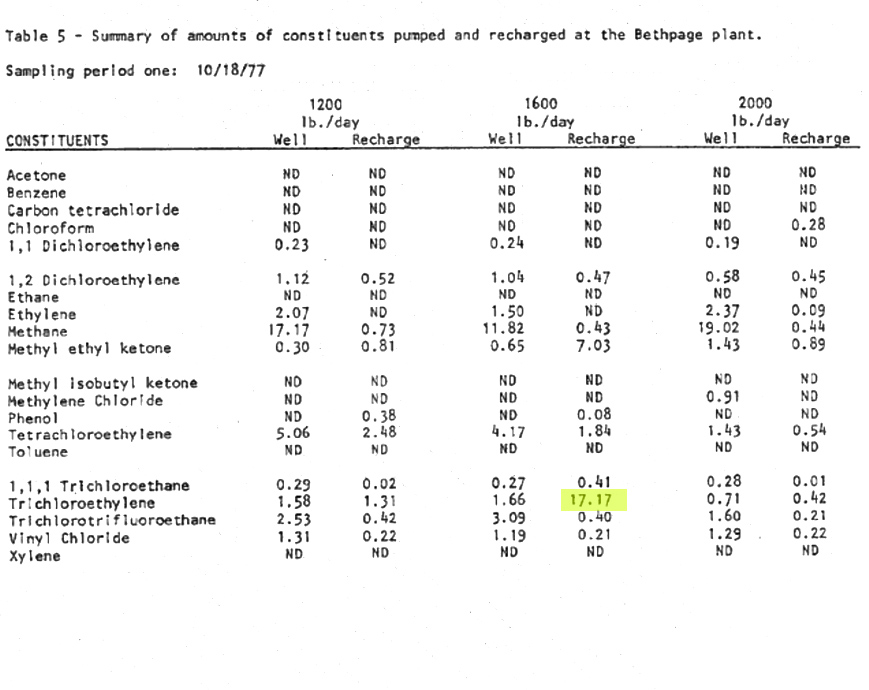

In June 1976, Grumman’s environmental consultants, Geraghty & Miller, presented the company with the confidential memo that pointed to the “basins, lagoons, spills, etc.” as the cause of the “slug” of pollution below ground. In an attached rendering, they labeled this source as part of Grumman’s facility. The memo offered four alternatives for how to deal with the situation.

In prescient terms, it also warned that the groundwater contamination, which had already shut several Grumman wells, “may spread both laterally and vertically beneath the property.” It cautioned that “neighboring wells may become contaminated over the long term” and that “further contamination may take place from sources presently not detected.”

All those projections came to pass. Officials today believe that the failure to acknowledge and act on them came at a big price.

“Slug may spread both laterally and vertically… Neighboring wells may become contaminated…”

1976 internal consultant memo to Grumman See full document“If they had done their job in the ’70s – ’76 – when they knew about the polluted wells; if they would have done their job then, we wouldn’t be here today,” said John Sullivan, chairman of Bethpage Water District’s board of commissioners.

Grumman didn’t tell employees or the public these findings, which were concluded with a call for the company to further investigate as it switched its drinking water supply to Bethpage wells to “eliminate the problem of potential adverse health effects.”

The general problem of groundwater contamination at the site only surfaced a half-year later when an alarmed state official with access to water sampling results called an Albany newspaper.

But the consultant’s precise analysis of what the future could hold didn’t emerge until now.

2. ‘I’D DRINK THE WATER’

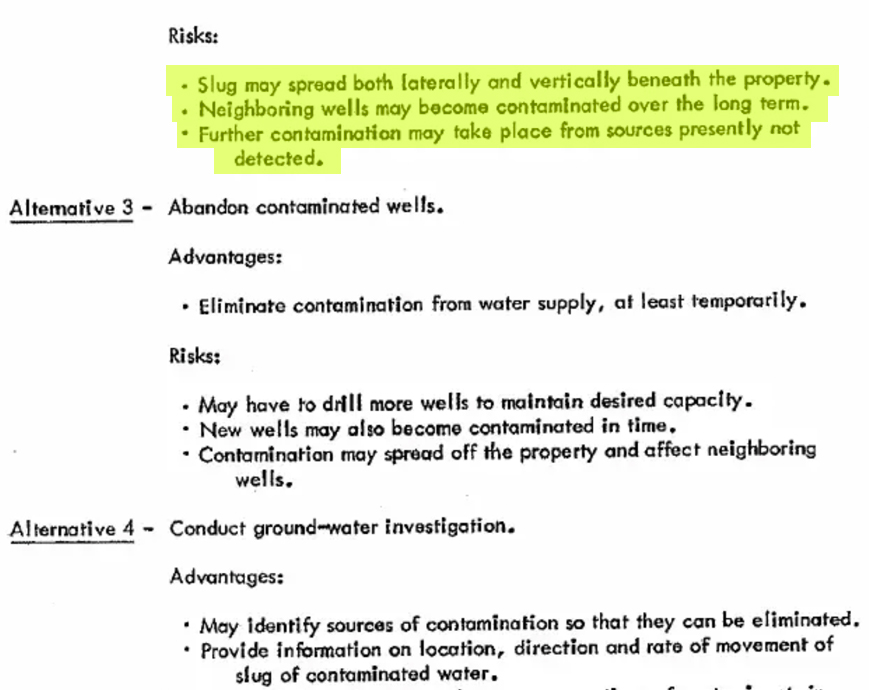

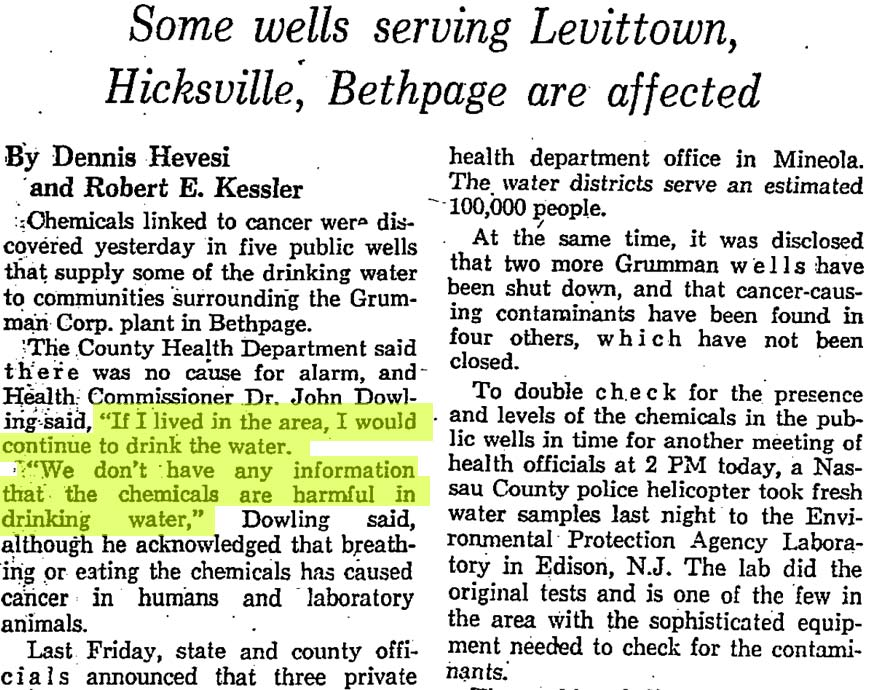

On Dec. 2, 1976, the Bethpage Water District received the first results showing that one of its public wells was contaminated with TCE. Readings would reach as high as 60 parts per billion, above the soon-to-be-approved state limit of 50.

The well had only been intermittently used in the months before, but Bethpage residents had still been drinking its untreated water for years. That morning, state, local and federal officials, including Nassau County Health Commissioner John Dowling, met with Grumman representatives to discuss the pollution’s spread from the company grounds into the community.

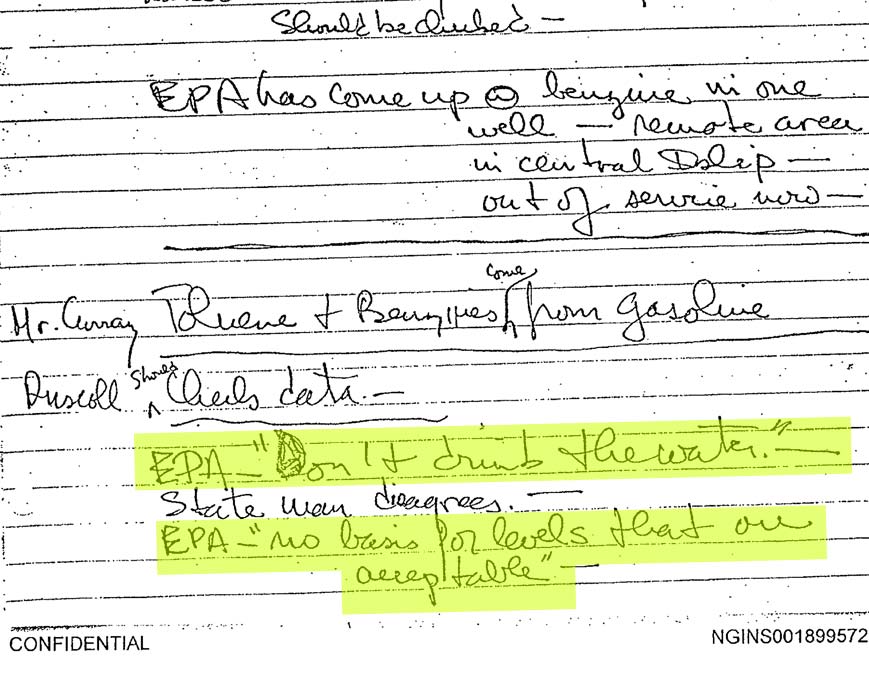

The meeting and its attendees were documented in confidential handwritten notes to Grumman by Geraghty & Miller, another of the Century Insurance documents.

It recorded a sharp disagreement between representatives of the federal Environmental Protection Agency and those of the state environmental department:

EPA — “Don’t drink the water”

State [illegible] disagrees

EPA — “no basis for levels that are acceptable”

“If I lived in the area, I would continue to drink the water. We don’t have any information that the chemicals are harmful in drinking water.”

Newsday, Dec. 3, 1976 See full article

“EPA – ‘Don’t drink the water.'”

“EPA – ‘no basis for levels that are acceptable.'”

Confidential memo detailing Dec. 2, 1976, meeting about Grumman contamination See full documentDowling, who is now deceased, told Newsday later that day: “If I lived in the area, I would continue to drink the water. We don’t have any information that the chemicals are harmful in drinking water.”

It was only last year that the New York Department of Health stated for the first time that levels of TCE in Bethpage public water before 1976 were high enough to harm people’s health.

3. ‘NO QUESTION REGARDING LIABILITY’

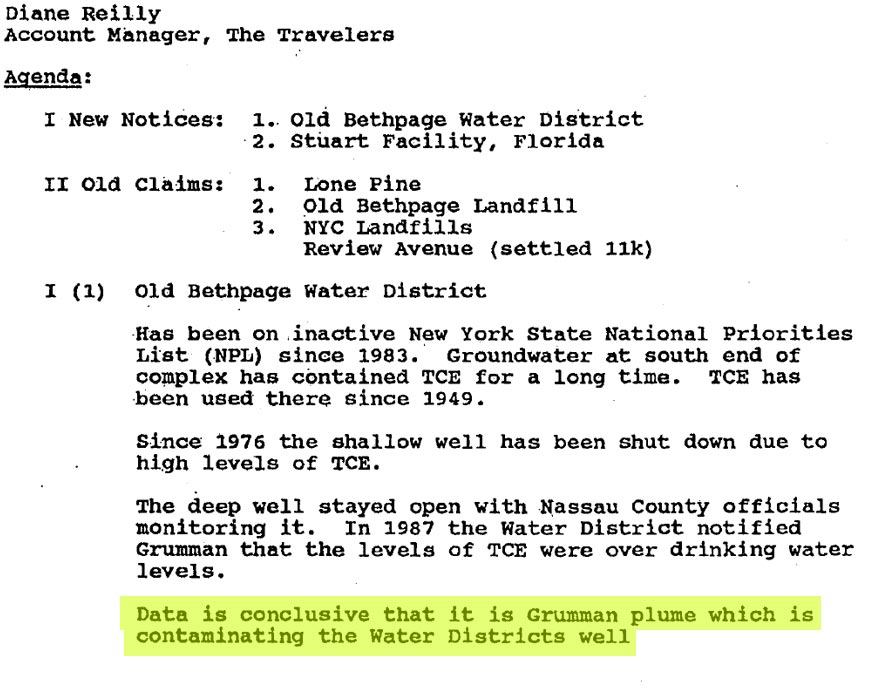

By August 1989, the Bethpage Water District had privately notified Grumman that a second of its public wells had been polluted with TCE. A company executive, along with an engineer, a lawyer and an insurance manager, huddled with Travelers representatives to discuss a possible settlement.

Another memo that was meant to be sealed offered a blunt summary of the closed-door discussion: “Data is conclusive that it is Grumman plume which is contaminating the [Bethpage] Water Districts [sic] well.”

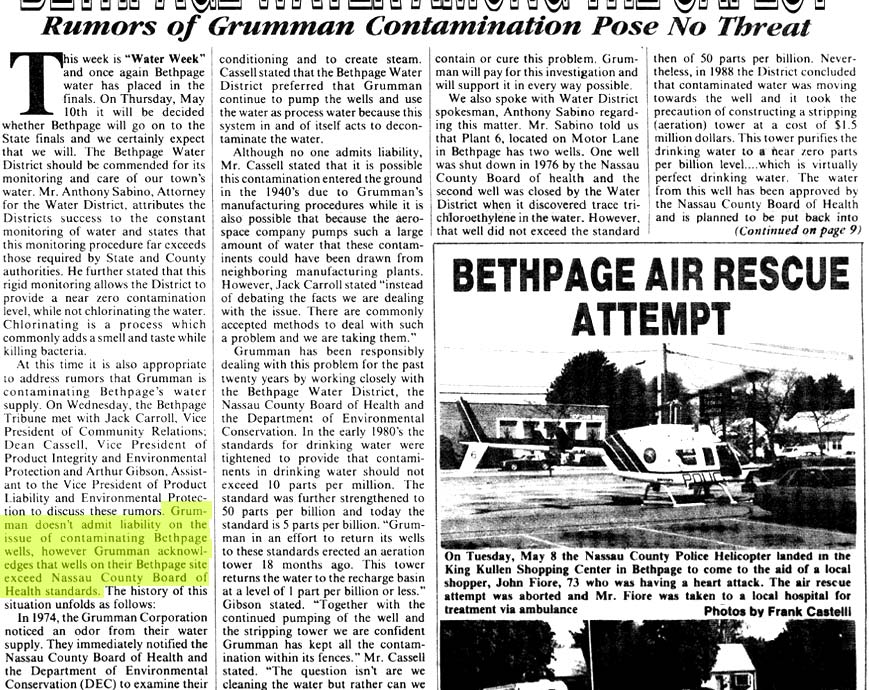

“Grumman doesn’t admit liability on the issue of contaminating Bethpage wells, however Grumman acknowledges that wells on their Bethpage site exceed Nassau County Board of Health standards.”

Bethpage Tribune, May 1990 See full article

“Data is conclusive that it is Grumman plume which is contaminating the Water Districts well….No question regarding liability…”

1989 memo summarizing internal meeting between Grumman and its insurer See full documentIt later underscored the point: “No question regarding liability as there are no other direct parties [that] appear to have contributed to contamination yet.”

Grumman didn’t come out of the meeting and acknowledge its role.

In fact, a few months later it did the opposite. One of the executives who attended the meeting was among a group of top Grumman officials that spoke to a community newspaper. They told it the company didn’t admit liability for the contamination.

The headline on the May 1990 story: “Bethpage Water Among the Safest: Rumors of Grumman Contamination Pose No Threat.”

Emerging in Newsday’s investigation, document by document and incident by incident, is the secret history of an environmental disaster that could have been contained long ago and a public that should have known more.

Reporters/writers: Paul LaRocco and David M. Schwartz Project editor: Martin Gottlieb Additional editing: Doug Dutton Project manager: Heather Doyle Video director, editor: Jeffrey Basinger Video producers: Basinger and Robert Cassidy Videographers: Basinger, Shelby Knowles, Howard Schnapp, Chris Ware and Yeong-Ung Yang Photo editors: John Keating and Oswaldo Jimenez Motion Graphics: Basinger Digital design/UX: Matthew Cassella and James Stewart Additional project management: Joe Diglio Social media: Anahita Pardiwalla Research: Caroline Curtin, Dorothy Levin and Laura Mann Copy editing: Don Bruce Graphics: Andrew Wong and Basinger Print design: Seth Mates