The plume: What’s in it, and what’s being done

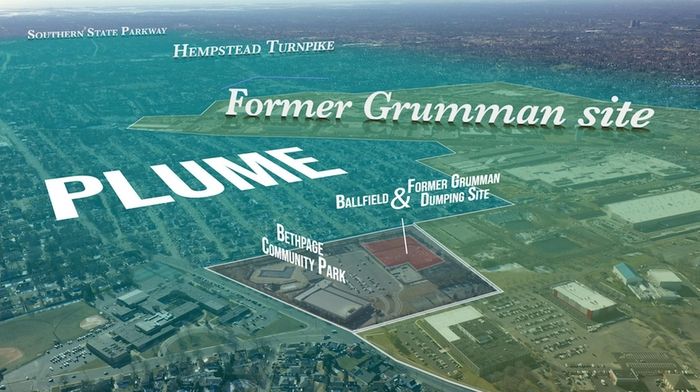

Map shows Grumman property and a representation of the plume's spread. Graphic by Jeffrey Basinger / Photo by Yeong Ung-Yang.

Long Island’s largest and most complex mass of groundwater pollution begins as two contaminant concentrations 50 feet below ground in Bethpage.

One starts from the western portion of the old Grumman Aerospace and U.S. Navy complex. The other originates from the east beneath Bethpage Community Park, once a Grumman waste site. They commingle beneath the southern portion of the former 600-acre manufacturing site to form a single plume.

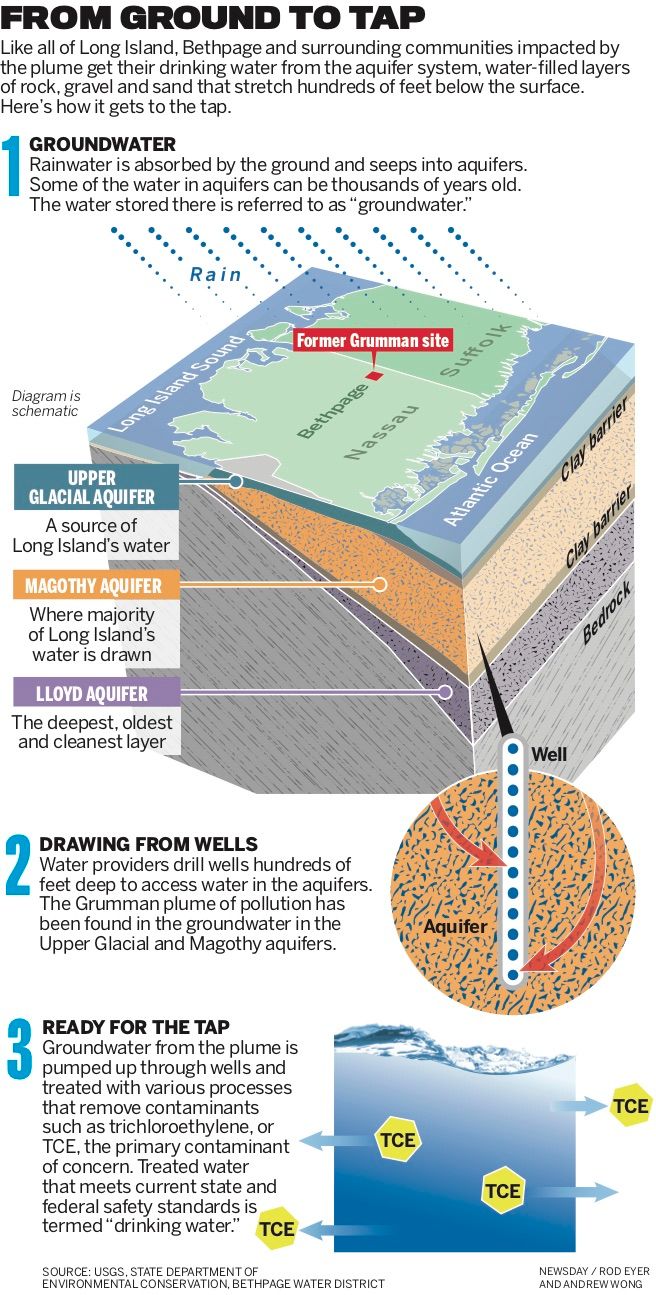

Indistinguishable in taste, texture or smell from uncontaminated water, the plume spreads roughly south or southeast at about a foot per day between the grains of sand and gravel bits that make up the region’s aquifer system. The flow is influenced by the makeup of the soil and the action of wells that pump drinking water and treat the pollution.

It now extends south 4.3 miles from the former Grumman site, with its leading edge past the Southern State Parkway. It stretches 2.1 miles wide toward Levittown and Bethpage Parkway, and goes as much as 900 feet deep until it runs into a layer of clay that separates it from the Lloyd aquifer, Long Island’s deepest and cleanest source of water.

The contamination was first identified in the groundwater in the 1940s. The pollution has required treatment at 11 wells that provide drinking water for Bethpage, Plainedge, South Farmingdale, North Massapequa and parts of Levittown, Seaford, Wantagh and Massapequa Park. It threatens another 16 public drinking water wells. In total, 250,000 Nassau residents get their water from affected wells or those in the path of the plume.

All drinking water pumped from the plume is treated to remove contaminants before it reaches people’s faucets. Almost without fail, the water has met government standards for safety for more than 40 years. The one exception was in September 2007, when a relay switch failed for 11 days on a treatment system. The district found 10 times the drinking water standard for the carcinogen trichloroethylene, also known as TCE or trichloroethene. The well, though, was only used intermittently for about 15 hours to meet high demand.

The state has said there’s no risk to living or working above the polluted groundwater.

New York State’s Department of Environmental Conservation first designated the site for cleanup in 1983 under the state’s Superfund program, which identifies former hazardous waste sites and manages their cleanup. In 1987, the state elevated the Grumman facility to a “level 2” Superfund site, which means it presents a “significant threat to public health or the environment.”

TCE is “known to be a human carcinogen,” according to the federal Department of Health and Human Services.The state has listed two dozen “contaminants of concern” for cleanup within the plume. Thirteen chemicals and metals are designated by federal agencies as carcinogens, likely carcinogens or suspected carcinogens.

They include solvents used to clean and degrease airplane and lunar module parts, additives used to make those solvents last longer and metals used in plating.

By far the most prevalent contaminant is TCE. It was used by Grumman as a solvent for parts. It has been found in untreated groundwater outside the former Grumman boundaries at levels of 13,700 parts per billion, 2,740 times higher than the drinking water standard of 5 parts per billion. (TCE levels of 58,000 parts per billion have been found in groundwater directly beneath former Grumman operations.)

The chemical is “known to be a human carcinogen,” according to the federal Department of Health and Human Services. Scientists have linked exposure to kidney and liver cancers, malignant lymphoma, testicular cancer, immune system diseases and developmental effects such as spontaneous abortion, small birth weight and congenital heart and central nervous system defects.

TCE, which in its pure form has a sweet smell, had been stored in a leaky 4,000-gallon tank at one of the Grumman plants.

The contamination also was caused by Grumman’s disposal and routine housekeeping practices. Chemicals have been found in old cesspools, dry wells and storage areas, as well as unlined pits where wastewater was dried into sludge and workers discarded dirty rags.

Besides TCE, the two most common plume contaminants are tetrachloroethene, also known as PCE or PERC, used as a solvent to clean aircraft parts; and cis-1,2-Dichloroethene, or cis-1,2-DCE, also found in solvents.

Thermal wells, which extract contamination from the soil, are visible on the ballfield at Bethpage Community Park in September 2019. The ballfield has been closed since toxic chemicals were discovered in 2002. Photo credit: Steve Pfost

Discovered in soil at the former Grumman site has been one contaminant not found in the groundwater — the now banned industrial compound polychlorinated biphenyl, or PCB. Soil has also been contaminated with volatile organic compounds like TCE and chromium, which was a metal plating agent.

One chemical the district is still working to remove is the likely carcinogen 1,4-dioxane, used by Grumman as a solvent stabilizer. It has been found in Bethpage Water District drinking water wells at levels up to 15 times higher than the state’s proposed standard.

The district began operating in October a treatment system for 1,4-dioxane in the first of its six affected wells. State health officials say 1,4-dioxane poses a slightly elevated risk of cancer after long-term exposure.

Northrop Grumman, which acquired Grumman in 1994, has for more than 20 years operated treatment wells at its former facility to remove contamination and prevent it from spreading further. The state estimates 200,000 pounds of contaminants, or 18,000 gallons, have been removed from the plume. It also estimates that another 200,000 pounds of contaminants remain.

In December 2009, Northrop Grumman began operating another set of wells to contain pollution coming from the eastern plume at Bethpage Community Park. The state estimates it has removed approximately 2,200 pounds of contamination.

Since 2009, the Navy has operated the only groundwater treatment wells outside the former facility grounds aimed at removing an area of the plume with a high concentration of contaminants. The system treats about 1.4 million gallons of water per day and has removed more than 11,000 pounds of contamination.

Northrop Grumman and the Navy are each constructing other treatment systems in Bethpage at “hotspots” that have elevated contamination levels. They are scheduled to open in 2021 and 2020, respectively. But they have resisted efforts to contain the plume as it continues to spread toward the Great South Bay.

The state has approved a $585 million plan to use a series of 24 wells and treatment systems to stop the plume from spreading and clean the underground water. It would cost $241 million to construct, plus millions more each year to maintain and operate. It would take 110 years to clean the entire groundwater plume to 5 parts per billion of contamination or less.

The Navy and Northrop Grumman have opposed the plan, saying it’s not feasible and that the public can be protected by treating water before it reaches faucets.