An aerial view of the Northrup-Grumman site in Bethpage in April 1999. Credit: Newsday / Ken Spencer

A few years after Grumman Aerospace first acknowledged a measure of responsibility for the significant groundwater pollution in Bethpage, state regulators turned to the company’s own consultants to predict how far it would spread.

The consultants concluded in 2000 that natural processes, coupled with treatments deemed minimal by water providers, would virtually eliminate the toxic plume and the need for a costlier cleanup.

The state’s Department of Environmental Conservation added a cover letter and adopted the report as its own, making it a critical guide to long-term decision-making.

The future did not work out exactly as predicted. Today, concentrations of the most troubling plume contaminant — the carcinogenic metal degreaser trichloroethylene, or TCE — are hundreds of times worse at numerous locations.

The wildly inaccurate projection epitomized how state environmental officials long acted hand-in-glove with Grumman and its successor, Northrop Grumman, in ways that served to limit corporate blame and expenses.

Together, they chronically underestimated what has become Long Island’s biggest mass of groundwater contamination and failed to curtail it almost anywhere beyond the original 600-acre Grumman complex.

There was simply no political will to adequately resource this issue.

Anthony Sabino, Bethpage Water District counsel

Newly uncovered documents show that the state dismissed tackling the plume more decisively from the start of the official cleanup process, in 1990. It continued endorsing lowball predictions even as a key Northrop Grumman manager sounded internal warnings that the pollution had expanded far more than expected.

“Sadly, the plume could have been substantially contained 30 years ago,” said Anthony Sabino, a retired attorney who battled polluters and regulators for more than two decades as Bethpage Water District counsel. “What we are facing is the complete failure of the state under many commissioners and project managers.

“There was simply no political will to adequately resource this issue.”

The state, reversing its longtime approach, recently approved a $585 million remediation, featuring the first full plume containment effort. It mirrors what local water districts essentially called for from the beginning, when the problem’s scope — and cost of fixing it — was far less.

The plan calls for Northrop Grumman and the U.S. Navy, the other responsible party as owner of about 100 acres of the old Grumman site, to foot the bill. Both have argued the plan is not scientifically based.

A new day?

While Grumman made no mea culpa, the 1990s dawned with the company displaying a new cooperation with both regulators and water providers.

In 1990, it quietly agreed to give the Bethpage Water District $1.7 million for the first system it installed to remove contaminants from its public wells. At the same time, the company was expanding a similar effort on its own property.

By 1998, that on-site containment network grew to include a barrier of five extraction wells that pump and treat 5.5 million gallons per day of contaminated water.

Throughout the ’90s and early 2000s, Northrop Grumman was following the state environmental Superfund process for industrial pollution sites, with little outward sign of obstinance.

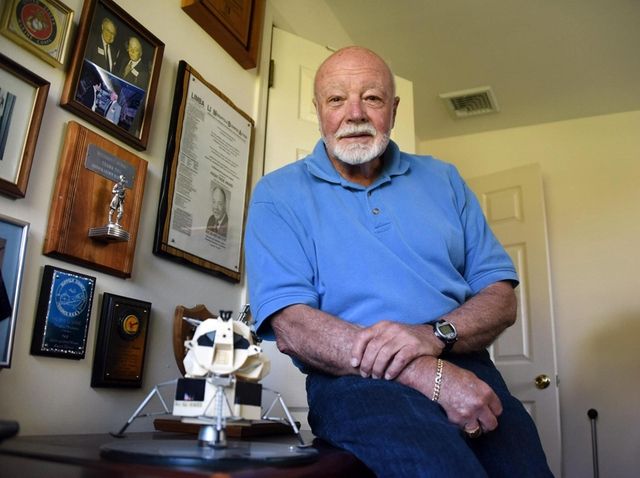

“We were lockstep with the DEC,” said Dick Dunne, Grumman and Northrop Grumman’s government relations and public affairs director between 1991 and 2002, using the acronym for the state’s environmental conservation department. “They were advising us on what we should and shouldn’t do. And we were listening.”

There were limits, however, and they now stand as critical ones.

Early on, Grumman agreed to stop further groundwater contamination from leaving its property. But with the state’s blessing, it essentially left it to the Navy to address the substantial mass that had already escaped.

Over time, that plume has continued spreading through Bethpage to threaten public water supplies serving communities including South Farmingdale and North Massapequa, as well as parts of Levittown, Seaford and Wantagh.

Dick Dunne, at his West Islip home in June 2019 with a small replica of the lunar module, worked for Grumman in the 1960s and ’70s and was the government relations and public affairs director for the company between 1991 and 2002. Photo credit: Danielle Silverman

In 1994, four years after its first agreement with the Bethpage Water District, Grumman paid it $1.8 million for a second contaminant removal system.

Counting maintenance and other associated costs, the company estimates it has paid $5.4 million to the Bethpage district for the two public treatment systems that decontaminate water before it reaches taps.

That compares to more than $40 million for public well treatments paid by the Navy, which also operates the only completed off-site system that extracts contaminants from the plume. (Northrop Grumman hopes to open its first in early 2021.)

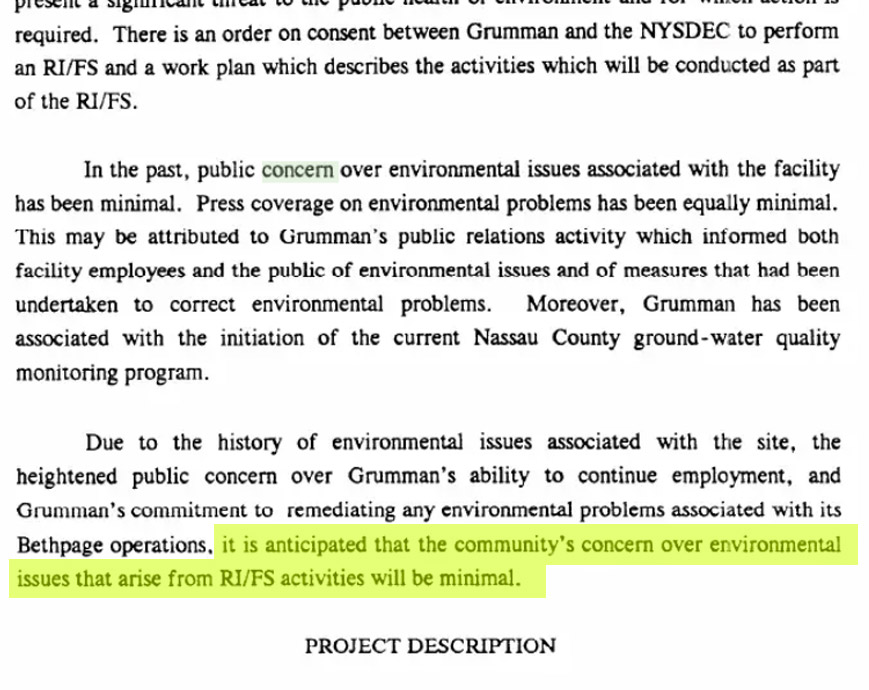

For a long time, few in Bethpage knew much of this sort of detail, and Grumman predicted that it could avoid any public outcry in the future.

“In the past, public concern over environmental issues associated with the facility has been minimal,” Grumman’s consultants, Geraghty & Miller, wrote to the state in July 1990, concluding that “heightened public concern over the company’s ability to continue employment” — it still had more than 18,000 workers — was one reason “it is anticipated that the community’s concern over environmental issues that arise … will be minimal.”

“… it is anticipated that the community’s concern over environmental issues … will be minimal.”

1990 citizen participation plan from a Grumman consultant to the state See full document‘Aligned’ with Grumman

The relationship between Grumman and the state was sympathetic from the outset of the Superfund process that governs state environmental cleanup efforts. This was the case even after Grumman was bought by Northrop Corp. in 1994 and its presence and workforce on Long Island shrank dramatically.

Referring to state environmental officials, Stan Carey, superintendent of the Massapequa Water District — the next water provider in the path of the plume — observed, “The people running the remedial program almost seemed like, at times, that they were aligned with the Navy and Grumman.”

To chart the extent of the state’s rulings favorable to the company, Newsday reviewed thousands of pages of documents from the voluminous reports issued in compliance with Superfund regulations.

These began after Grumman signed an agreement with the state in October 1990 to develop a Remedial Investigation/Feasibility Study, known as an RI/FS, to probe the extent of the mess and how best to treat it. That would lead to a binding cleanup plan, known as a Record of Decision.

The alliances, disputes and road to half measures began at the start.

Some parties deeply involved in the crisis immediately argued that containing the plume was the fundamental issue. At a December 1990 public hearing on the study, Sabino said he’d “declare war” on regulators if they didn’t fully investigate the groundwater contamination and try to stop its spread.

But the state dismissed that premise.

It said in a 1991 reply to his and other public comments that a full plume containment “would be a waste of time and money.”

“It could make matters worse,” the state wrote. “For example, a public supply well which otherwise would not be impacted by the plume, could become contaminated (i.e. – the plume could be deflected.)”

In their reply, they also dismissed, as not “finely tuned,” the only study that had mapped the spread of contaminants from Grumman’s property. Up until that point, the 1986 finding by Nassau County and the U.S. Geological Survey had been considered a landmark — so significant that it caused the state to elevate the site’s Superfund risk level, kicking off the remedial process.

Richard Humann, president and CEO of H2M architects + engineers of Melville, speaks to the Oyster Bay Town Board about the plume in February. Photo credit: Howard Schnapp

The decision not to seek full containment reverberated for decades.

“That was a fatal-flaw decision,” said Richard Humann, president and CEO of H2M architects + engineers of Melville, a longtime environmental consultant for the Bethpage Water District. He called it “a conclusion reached with insufficient information,” one that “set the stage for a series of underestimates and a series of minimizing what the potentials could be.”

‘Not considered’ a source

In early 1992, the state issued a fact sheet that made clear the focus of its first formal cleanup plan would be the contaminated soil on the Grumman and Navy grounds, not the plume spreading beyond their borders.

“An offsite groundwater investigation(s) will also be performed (as a separate phase) if it is determined that more data are necessary to complete” the study, the state wrote.

Who would conduct the study? “The RI/FS will be performed by Geraghty & Miller Inc., a local environmental services firm with over 30 years of experience,” officials wrote, without noting the company had worked for Grumman for years.

Geraghty & Miller would become part of Arcadis Inc., an international environmental firm that continues to work for Northrop Grumman.

The state’s Record of Decision, released in March 1995, called mainly for the newly formed Northrop Grumman company to install soil contaminant removal systems on its property, including one near a massive storage tank that had leaked TCE into the ground during the 1970s. The Navy, under a report specific to its property, was required to take similar action.

But the most telling details in the 1995 Grumman decision came from some of the dozens of questions gathered from the public during the hearings the year before.

“Why is a consultant working for Grumman developing a remedy for addressing the groundwater contamination?” one person asked.

The state replied that Grumman was required to hire a qualified consultant and that Geraghty & Miller fit that description. It added that state environmental officials would approve all findings.

“Had a remedy been put in place several years ago, how much less pollution would have migrated off-site, and how much less of a problem would we be facing today?”

“Certainly, additional contamination has migrated off site over the past few years,” officials wrote in response. “However, in the opinion of the NYSDEC, the overall magnitude of the problem has not increased significantly.”

A question posed in another comment was understandable to anyone who had spent time in Bethpage: “Have there been any investigations of properties formerly owned by Grumman (e.g., Bethpage Community Park)?”

The 18-acre plot, on the eastern edge of the company’s grounds, had been gifted to the Town of Oyster Bay by Grumman in 1962. It opened two years later as a sparkling focal point of suburban life, one that eventually included a swimming pool, playground, ice skating rink and ballfield where generations of children gathered.

“You met everybody in town. Everybody went to the ice rink. Everybody went to the pool. Everybody played sports in the park,” recalled Mark Comerford, 67, a Bethpage native. “I basically grew up at that park.”

The state’s confidence in the safety of the park was evident in its response to the public comment. “A direct investigation of the Bethpage Community Park was not conducted,” the state wrote, noting that groundwater monitoring wells had been installed immediately south of the site. “Based upon the current data, the Park is not considered to be a source area.”

A year earlier, the Navy had taken a single sample inside the park as part of a wider investigation into whether soil with the toxic industrial compound polychlorinated biphenyl, or PCB, had blown off its original site. It only tested for the carcinogen, however, at a depth of up to 6 inches and did not find enough to trigger further testing or public disclosure.

Skaters at the ice rink at Bethpage Community Park in December 1996. Photo credit: Newsday / Jim Peppler

Though soil cleanup on Grumman’s property was its focus, the state signaled in the 1995 decision that it would look deeper into the spread of the plume. “A groundwater model has to be developed,” it wrote.

Then, launching a six-year process that mirrored the one just completed, the state and the Northrop Grumman consultants issued a new round of reports specific to the plume. Most notable was another company-authored feasibility study and a second Record of Decision.

During this time, the plume grew by nearly a mile, down past Hempstead Turnpike.

Meanwhile, the company and the Navy agreed, in what a federal judge later called an “informal ‘handshake agreement,'” to divide responsibilities for what was to come.

Northrop Grumman, after funding the Bethpage Water District’s first two public supply treatment systems, focused its efforts on completing and operating its large on-site containment system, part of what it says has been a $200-million remediation commitment over the past 30 years.

The Navy in 1995 paid $1.9 million for Bethpage’s third contaminant removal system. Against a backdrop in which the state and consultants for the company were predicting minimal future plume impacts, the Navy also agreed to fund any similar treatments that might be required, whether off-site containment wells or further public treatments.

To date, the Navy has accrued costs of more than $45 million for the public contaminant removal systems. Its total costs come to more than $130 million, a Navy spokeswoman said.

Public underestimation, private alarm

In October 2000, the state released the feasibility study that led to its plan for dealing with the growing plume.

It serves as a flashing warning sign for how the spread and severity of contamination were profoundly misjudged.

To start, Arcadis estimated that it would take at least three decades for the plume to reach further public water supplies.

It took one.

The report stated that TCE-contaminated groundwater at one public Bethpage well would be reduced to state drinking standards of 5 parts per billion by 2012. Instead, the levels increased to 83 parts — and in 2019 stood at 349.

Perhaps most inaccurately, the feasibility study stated that any portion of the plume not cleaned up by treatment systems proposed or already in place would “undergo natural attenuation.” That meant that the toxic chemicals would ultimately dilute or be removed through various organic physical, chemical or biological processes. As the state determined in 2019, after reversing its approach to the crisis, “it is clear that natural attenuation alone in these areas would not significantly contribute to attaining groundwater quality standards.”

On their own, the feasibility study’s botched projections are glaring enough. They stand out even more when contrasted with the internal alarms set off, almost simultaneously, within Northrop Grumman.

On Oct. 30, 2000, two weeks after the Arcadis report, Larry Leskovjan, then manager of Northrop Grumman’s environmental, safety, health and medical operations, alerted colleagues in an internal memo of a “recent discovery that the contaminant plume has progressed much more closely to the South Farmingdale Water District supply wells than expected.”

The memo is cited in a 2014 decision by U.S. District Court Judge Katherine B. Forrest finding that Grumman’s former insurers would not have to cover environmental damage claims against Grumman, in part because the company kept it in the dark about its exposure.

Leskovjan added that data “strongly suggest[s] that this plume originated from Northrop Grumman property.” The admission was one the company still hadn’t quite made publicly, even as it acknowledged some responsibility to state regulators.

A month later, according to Forrest’s ruling, the company confirmed Leskovjan’s warnings at a meeting with representatives of the Aqua Water District, a private provider (now known as New York American Water) with wells serving Seaford and Wantagh. Northrop Grumman revealed, Forrest wrote, that it “knew that contamination emanating from its Bethpage facility … was expected to eventually contaminate the drinking water supplies of both” that district and South Farmingdale.

In an email three months later, Leskovjan said the water districts were concerned “as a result of recently developed information that indicates [Grumman’s] groundwater plume extends much farther than anticipated.” He later noted that it was his “understanding in 2001 that Northrop Grumman potentially might be responsible for costs associated with insuring a clean water supply” to those districts, Forrest wrote.

The Navy, however, under its “handshake” deal with Northrop Grumman, was the one that ultimately paid those costs — nearly $28 million, according to its records.

Lack of urgency

Leskovjan’s warnings were not truly reflected in the state’s March 2001 Record of Decision on the groundwater plume, its first formal plan for remediating the contamination outside the former Grumman plant.

Even though the plume now covered about 2,000 acres, with its southern edge crossing Hempstead Turnpike, the state did not call for the urgent action local officials wanted.

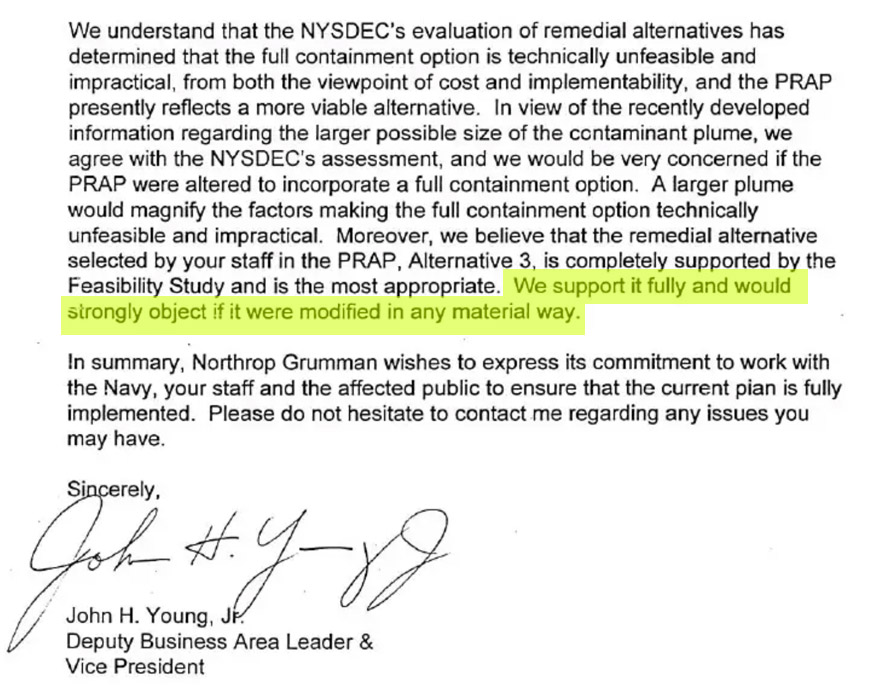

“We support it fully and would strongly object if it were modified in any material way.”

2001 letter from Grumman to state DEC See full documentEstimated to cost $33.6 million, the plan recommended three primary components: continuation of Northrop Grumman’s on-site containment, continuation of the drinking water treatments at public wells in Bethpage and a single new off-site contaminant removal system 4,500 feet south of a former company dumping site, to be funded and run by the Navy.

The unchosen alternatives were far more aggressive. At roughly double the cost, one called for a bank of pollutant extraction wells to rid the groundwater of toxic chemcials as they reached the outermost points of the plume.

The state, however, concluded that permitting and property acquisition would be “difficult to implement” and that building the extensive apparatuses required would be “impractical.” The Navy echoed these conclusions two years later in its own Record of Decision, which it was required to file as a federal department.

One foot per day, it travels …. It was Hempstead Turnpike. Now it’s the Southern State Parkway. Where’s it going to be next?

John Caruso, Town of Oyster Bay public works official

Had any of the alternatives been chosen, local water providers say, the plume could have been largely contained not far south of Hempstead Turnpike, lowering the likelihood that further public wells would have been affected.

“One foot per day, it travels,” said John Caruso, a Town of Oyster Bay public works official who has studied the contamination since he helped Nassau County develop the first plume map in the 1980s.

“It was Hempstead Turnpike. Now it’s the Southern State Parkway,” Caruso said. “Where’s it going to be next?”

The state’s approach, however, was heartily backed by Northrop Grumman and the Navy.

“We support it fully and would strongly object if it were modified in any material way,” John H. Young Jr., a Northrop Grumman vice president, wrote to the state in early 2001. “We would be very concerned if the [proposed plan] were altered to incorporate a full containment option.”

In its own Record of Decision, the Navy concluded, “It is not economically or technically feasible to contain and treat all the contaminated groundwater that has migrated from the [Navy] site to groundwater quality standards.”

A year later, reality hit hard through an unexpected discovery.