Despite progress after hate crime, SCPD and Hispanics struggle with trust

A gang of teens attacked Ecuadorian immigrant Marcelo Lucero in 2008 in a fatal hate crime that led to a federal probe into how Suffolk polices Hispanic communities. Despite progress, the SCPD still struggles to gain trust.

Ten years ago next Thursday, a gang of teenagers attacked Ecuadorian immigrant Marcelo Lucero on a Patchogue street in a fatal hate crime that sparked international outrage because of its casual brutality. Although local officials said the killing was an aberration, court records later showed that “beaner-hopping,” as it was known among these teens and the day laborers they pursued, was a regular pastime.

Even worse, investigators found, Suffolk police had shown little interest in looking into the attacks.

An indictment unsealed two months after Lucero’s killing revealed that in the 13 months before his death, the same teens, in small groups with shifting members, had gone on a spree of violence, assaulting at least 12 other Hispanics, including three men who said they reported the attacks to police but received little follow-up.

Those men were not alone. Scores of Hispanics came forward to say they had been harassed or beaten and that police were, at best, indifferent. The Suffolk police department said it was unaware Hispanics had been targeted, as did then-Suffolk County Executive Steve Levy, who frequently spoke out against illegal immigration.

‘There wasn’t just neglect of the Latino community, there was open hostility.’ -Jonathan M. Smith, ex-U.S. Department of Justice attorney

The complaints had a disturbing similarity: Hispanic men, walking alone usually at night, were set upon, assaulted and frequently robbed. When they reported the attacks to police, they said, officers minimized the incidents or merely filed reports and frequently failed to follow up.

“There wasn’t just neglect of the Latino community, there was open hostility,” said Jonathan M. Smith, a former U.S. Department of Justice attorney who was involved in the case and who now runs a nonprofit civil rights group in Washington.

Lucero’s death and the pattern of attacks spurred the U.S. Justice Department to launch an investigation. In December 2013, it entered into a monitoring agreement with the county that was designed to overhaul police performance in five broad areas and to last three years.

Last month, after more than four years in which Suffolk police failed to reach substantial compliance in any of the target areas, it achieved that goal in two, according to a Justice Department report: combating hate crimes and investigating complaints against its officers. In the other target areas, which include eliminating biased policing, improving translation services and relating better to the community, police showed meaningful progress but still fell short of success, despite years of fits and starts.

The Department of Justice’s progress report for SCPD

Both Suffolk Police Commissioner Geraldine Hart and Chief of Department Stuart Cameron said in an interview that they regarded the Justice Department’s continued monitoring as a positive.

“The goal is not to get the DOJ out of here, the goal is to keep making the department better,” Cameron said.

Despite the progress, the Justice Department’s latest 18-page report included a conclusion that could have been written after Lucero’s death:

“Our conversations with community members continue to reveal a persistent mistrust of SCPD.”

The Justice Department has cited that mistrust repeatedly in earlier reports.

Cameron said it is partly because of cultural differences since many immigrants come from countries where they don’t trust police and because many residents don’t differentiate between county and federal agents.

Still, the Justice Department conclusion was notable for reasons beyond the community’s lingering suspicion. First, the department urged police to build bridges not just for their own sake, but to improve crime fighting by establishing a trust that would lead to tips and cooperation within immigrant communities.

Second, the assessment comes amid Trump administration policies and rhetoric pointed at immigrants living in the country illegally and heightened law enforcement efforts against the vicious Salvadoran gang MS-13. These have led to hundreds more immigrant detentions on Long Island, including more than 30 that have been successfully contested in court.

As the crackdown has brought quiet to streets in immigrant communities, it raises the question of whether it also has fueled a mistrust that undermines the improvements attained through the Justice Department agreement.

“My sense is that the progress has been largely lost,” Smith said. “All the hysteria around MS-13 has driven a deeper wedge.”

‘We are looking for every opportunity that we can, even outside the parameters of the DOJ agreement, to go even further and make sure that we are doing what we can to connect with the community.’ -Geraldine Hart, Suffolk police commissioner

Hart said the department received a $1 million grant to fund gang prevention programs and that the department is utilizing social media for community outreach and has even sent commanding officers to people’s homes.

“We are looking for every opportunity that we can, even outside the parameters of the DOJ agreement, to go even further and make sure that we are doing what we can to connect with the community,” she said.

Suffolk District Attorney Timothy Sini served as police commissioner during a spree of violence attributed to MS-13 from January 2016 through October 2017 during which at least 16 youths were killed in Suffolk alone. Sini said the department had built bridges to the community by cracking down on MS-13. Making arrests and ramping up policing yielded tips from residents that helped solve murders and prevent other gang crimes — including the attempted abduction of a teenage boy MS-13 had targeted for death.

“Do we have a perfect operation? Of course not,” he said.

“I think that, by and large, the police department before me and after me does a tremendous job. And I think it can always improve,” he said.

But those in the immigrant community who have experienced waves of detentions still feel wary, said Patrick Young, program director of CARECEN, a nonprofit immigrant-rights group that provides counseling and legal services. “People are just frightened of them now,” he said of police.

Suffolk history

The county’s relationship with its burgeoning Latino population is one filled with twists, turns and points of friction.

A 1983 federal civil rights lawsuit cited the county for discriminating against women and minorities, including Hispanics, in hiring and promotion. Suffolk, along with Nassau, which was also named, agreed to a federal consent order that required it to pay $500,000 in damages, create a new hiring test and employ job-seekers who were discriminated against in past tests.

The consent decree is still in effect. As of October, roughly 10 percent of Suffolk’s sworn officers were Hispanic, according to police statistics.

Three years after that lawsuit, the county’s relationship with its Hispanic population took a different direction. In 1986, Democrats in the Suffolk County Legislature, responding to a newly passed national law that required employers to verify the legal status of employees, pushed the county to accept people fleeing civil wars in Central America. It officially designated the county a place of sanctuary for refugees, who had begun to settle in Brentwood and surrounding communities, where there were plenty of jobs for unskilled workers.

Then, as the population of immigrants grew to more than 7,000, attitudes shifted. By 1993, the sanctuary resolution was reversed.

By the mid-2000s, Levy’s rhetoric was grabbing headlines. He said foreign women who had children in the United States were having “anchor babies” and once joked at a roast that he’d have to deport “the guys back there in the kitchen.”

Early in his administration, Levy proposed deputizing county police as immigration agents, which would have allowed them to question people about their immigration status and detain and deport them, an idea that was criticized at the time by Jeff Frayler, then-president of Suffolk Police Benevolent Association.

"Right now, we’re giving a significant portion of the minority community reasons to distrust the police," he told Newsday.

In an interview, Levy, a lawyer who also writes a column for the Conservative online publication Newsmax, disputed persistent criticism that he stoked intolerance, saying it was a myth “perpetrated by the media.”

He said his statements reflected the concerns of taxpayers dealing with immigrants living here illegally in overcrowded housing and competing for work as cheaper labor.

“You had house after house with dozens of people in them, and no one was doing a darn thing about it,” Levy said. “People were seeing their neighborhoods turned upside-down, and it wasn’t racial. It was density.”

Challenged at the time on his rhetoric and policies, Levy stood firm. “The public is in agreement with me,” he declared.

He was right. When Levy ran for re-election in 2007, he won with 96 percent of the vote, as a Democrat endorsed by Republicans.

A deadly attack

On Nov. 8, 2008, Lucero’s murder changed the political landscape.

Lucero, 37, was set upon near the Patchogue train station by seven teenagers he had never met in an assault that was shocking not just for its randomness, but because of the casual way in which the teenagers described attacking local Hispanics, according to police statements.

It was nothing more than a pastime, one of the teens, Anthony Hartford, 17, told police. “The last time I went out jumping beaners was Monday, Nov. 3, 2008 . . . I don’t go out doing this very often, maybe only once a week.”

Jeffrey Conroy, 17, who later was convicted of fatally stabbing Lucero, asked police, “Is this going to be a problem with wrestling season?” Another teen in the group asked if he would have to miss the Giants game.

There had been talk within the Hispanic community of unprovoked attacks before Lucero’s killing. After his death, the stories became public.

‘This was a kettle ready to boil over.’ – The Rev. Dwight Lee Wolter, who presided over Lucero’s funeral at the Congregational Church of Patchogue

The Rev. Dwight Lee Wolter, who presided over Lucero’s funeral at the Congregational Church of Patchogue, set aside a room in his church with a translator, where Hispanics could come forward to tell their stories to officials. More than 50 people showed up, and they gave such searing accounts of abuse — not just by roving gangs, but by landlords and employers — that the translator couldn’t stop crying, Wolter said. Woven throughout their accounts were reports of police indifference.

“This was a kettle ready to boil over,” Wolter recalled.

Many of the beating victims came in with yellow pieces of paper, copies of police reports they had filed. The assaults were each listed as an “incident,” never a hate crime, Wolter said.

The year before, in 2007, only one anti-Hispanic hate crime had been reported in Suffolk County.

“It was a different attitude, or they just never followed up,” Lucero’s brother, Joselo, said in a recent interview of the police.

All seven teenagers charged in connection with Lucero’s killing were convicted of charges from first-degree assault to first-degree manslaughter as a hate crime. Their sentences ranged from five to 25 years.

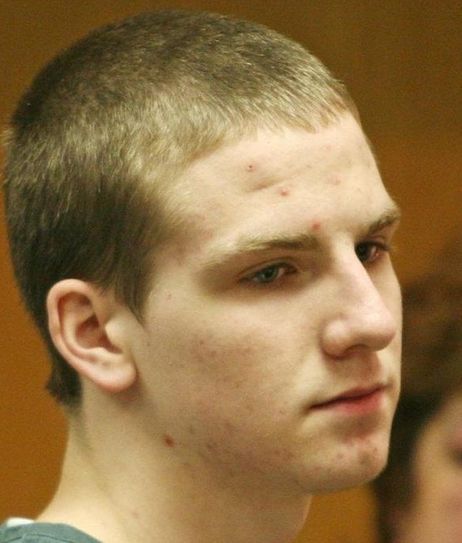

The ‘Patchogue 7’

He was 17 at the time of the attack.

His role in the crime/convictionsHe was convicted of first-degree manslaughter as a hate crime for fatally stabbing Marcelo Lucero. (While testifying at his trial, he said it was another teen, Christopher Overton, who was the killer.) He was also convicted of second-degree attempted assault as a hate crime in attacks on three other Hispanic men, including Lucero’s friend Angel Loja, first-degree gang assault and fourth-degree conspiracy.

StatusCurrently in prison serving a 25-year sentence. He will be eligible for parole on April 9, 2030.

2 2 Jordan Dasch

He was 17 at the time of the attack.

His role in the crime/convictionsHe pleaded guilty to first-degree gang assault and fourth-degree conspiracy in the Lucero attack. He also pleaded guilty to second-degree assault as a hate crime and second-degree attempted assault as a hate crime in connection with two other attacks earlier that day.

StatusReleased from prison on Aug. 26, 2015, on parole after serving almost five years of his seven-year sentence.

3 3Anthony Hartford

He was 17 at the time of the attack.

His role in the crime/convictionsHe pleaded guilty to first-degree gang assault in the Lucero attack and to four counts of second-degree attempted assault as a hate crime for attacks on four other Hispanic men.

StatusReleased from prison on Dec. 31, 2014, on parole after serving four years and three months of his seven-year sentence.

4 4Christopher Overton

He was 16 at the time of the attack.

His role in the crime/convictionsJeffrey Conroy tried unsuccessfully to blame Overton for the stabbing of Lucero. Overton pleaded guilty to first-degree gang assault in connection to Lucero’s death, fourth-degree conspiracy and second-degree attempted assault as a hate crime in attacks on two other Latino men. At the time of Lucero’s death, Overton was on probation awaiting sentencing for his role in a 2007 home invasion that ended in an East Patchogue man’s death.

StatusSentenced to six years in prison, with five years of supervised release, according to a NYS Department of Correctional and Community Supervision spokesman. He was paroled on Nov. 4, 2014, violated his parole and sent back to prison on Dec. 4, 2015. He was released again on parole on April 18, 2016, and will remain on supervised released until Nov. 4, 2019.

5 5Jose Pacheco

He was 17 at the time of the attack.

His role in the crime/convictionsHe pleaded guilty to first-degree gang assault in connection to the Lucero killing. He also pleaded guilty to fourth-degree conspiracy and three counts of second-degree attempted assault as a hate crime for attacks against other Latinos.

StatusReleased from prison on Nov. 5, 2014, on parole after serving four years of his seven-year sentence.

6 6Nicholas Hausch

He was 17 at the time of the attack.

His role in the crime/convictionsHe pleaded guilty to first-degree gang assault and fourth-degree conspiracy for his role in the Lucero attack. He also pleaded guilty to second-degree assault as a hate crime and second-degree attempted assault as a hate crime in connection with attacks on two other Hispanic men.

StatusHe was released from prison on July 9, 2014, on parole after serving three years and eight months of his five-year-sentence.

7 7Kevin Shea

He was 17 at the time of the attack.

His role in the crime/convictionsHe admitted to punching Marcelo Lucero in the face before the victim was fatally stabbed and to involvement in assaults on three Hispanic men including Lucero’s friend Angel Loja. He pleaded guilty to first-degree gang assault, second-degree attempted assault as a hate crime and fourth-degree conspiracy.

StatusReleased from prison on Sept. 11, 2015, on parole after serving five years of his original eight-year sentence.

Click on a number to learn more about each of the young men convicted in the Lucero attack. Photo credit: James Carbone

All have been released but Conroy, who was sentenced to 25 years and is imprisoned at the Clinton Correctional Facility, not far from the Canadian border. Tall and trim, with short-cropped hair, he became angry when a Newsday reporter visited him unannounced, and he refused to be interviewed.

The others did not respond to requests for interviews.

Justice Department steps in

Armed with the complaints from the Hispanic community, activists petitioned the Justice Department to intervene. In 2009, the department’s civil rights division started an investigation.

As investigators began their work, a different kind of violence hit the community hard.

In February 2010, four MS-13 members, believing that 19-year-old Vanessa Argueta had shown “disrespect” by sending rival gang members to attack one of them, lured her to a vacant lot in Central Islip. According to federal prosecutors, she had brought along her 2-year-old son, Diego Torres, because she couldn’t find a baby-sitter. The killers shot her in the head and chest as Diego cried and clutched the leg of one of them. They then shot him, reasoning that if they let him live, he would one day seek revenge, the prosecutors alleged.

Their killers were caught and convicted. Three of the four were sentenced to life in prison, and the fourth was sentenced to 45 years.

Though the hate crime that felled Lucero and the gang violence that claimed Argueta and her son may not appear connected, the Justice Department took note of both types of crime in a September 2011 letter to Levy. It outlined ways in which the department should handle hate crimes and, with an eye toward the growing gang problem, urged police to establish gang prevention units at the precinct level where they would be most directly involved with the community.

The letter provided recommendations aimed at improving the department overall.

“This is not just about police legitimacy and the legitimacy of the law,” said Christy Lopez, a former Justice Department lawyer who led civil rights investigations into police departments across the country and negotiated the Ferguson, Mo., settlement in 2015 after the fatal shooting a year earlier of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, by a police officer. “It’s about the effectiveness of policing.”

In December 2013, the county and Justice Department agreed that the department would monitor Suffolk police for three years. But because the department has failed to reach substantial compliance, the monitoring has continued, as the Hispanic community in Suffolk has expanded to more than 270,000, or 18 percent of the county’s population, according to the U.S. Census.

In the seven assessments that followed, the federal monitors provided a rare and detailed look at the internal workings of a suburban police force struggling to change its culture and connect with a wary community it has committed to serving better.

Over the years, according to the Justice Department assessments, monitors found “disturbing patterns” in Internal Affairs investigations of police misconduct. They were plagued by long delays — in some cases, more than two years. In addition, community members told “troubling stories” about being rebuffed when they tried to file complaints against police.

In 2016, the department’s anti-bias training program was suspended because it was riddled with problems, with instructors undermining it with an “us against them” mentality. One instructor told her class, “I know this frustrates you, but this is what we have to do.”

‘SCPD has demonstrated little to no involvement by the patrol and investigative units in community and problem-oriented policing.’ – Department of Justice report in December 2015

Several reports faulted the department for failing to fully engage the community — or its own officers — in its efforts. “SCPD has demonstrated little to no involvement by the patrol and investigative units in community and problem-oriented policing,” the monitors said in a December 2015 report.

The lack of translation services and interpreters has been a particular problem. A report last year noted that officers on patrol had such difficulty using the department phones to link non-English speakers to translation services that they began using their own cellphones instead.

But federal monitors have cited meaningful improvements, as well. In the last six months, the department has reached substantial compliance in two areas: tracking hate crimes and hate incidents, and investigating allegations of police misconduct.

The police department achieved success in the hate-crime category by overhauling its training and launching a reliable system for mapping hate crimes — a critical tool for preventing deaths like Lucero’s. Federal monitors applauded the department’s decision to make the mapping data public “to bolster transparency.”

As for police misconduct, the department has gone beyond the requirements of the monitoring agreement. In addition to reducing delays in completing Internal Affairs investigations — the average investigation now lasts 91 days — police have implemented a policy to keep complainants apprised of the status of their complaints.

Earlier Justice Department assessments credited Sini with revamping the Internal Affairs Bureau by adding staff, training and higher-ranking officers.

Still, between 2013 and 2017, there were at least 134 complaints about biased policing, racial profiling or civil rights violations involving Suffolk police. None of the complaints was substantiated by Internal Affairs investigators, according to data obtained through a Freedom of Information request in a lawsuit alleging police bias.

In response to a question from Newsday, the department issued a statement saying that the Justice Department did not find any of its investigations deficient.

Smith, the former Justice Department attorney, said the failure to substantiate any complaints of biased policing is “a huge red flag.”

The question of what happens at traffic stops has been particularly vexing for Suffolk police. A Newsday investigation last year found that Hispanics and other minority group members were arrested nearly five times more than whites on Long Island on charges like resisting arrest and a variety of drug offenses that typically stem from traffic pullovers. Experts told Newsday the charges were the result of the suburban equivalent of “stop-and-frisk.”

Data analysis is critical in determining what factor bias plays in these stops, but Suffolk police have experienced years of failure in being able to track the encounters.

In 2017, Suffolk police scrapped a data system developed by an outside vendor because it generated thousands of incomplete entries. But when they replaced it with their own software, the system failed on its first day. Patrol officers repeatedly complained that it was unwieldy and took too long to complete.

In the most recent assessment released in October, federal monitors noted that police have implemented a robust data collection system that is projected to yield its first comprehensive results in a year.

Nonetheless, community advocates remain skeptical and question whether technical changes and policy directives trickled down to the rank and file. The DOJ monitoring has been “a force for good and change,” said Walter Barrientos, a consultant for the Brentwood-based advocacy group Make the Road New York. While the department made some strides “on paper,” he said the average Latino immigrant still receives poor treatment from police.

Joselo Lucero, who worked at a dry cleaner with his brother, became an immigrant advocate after Marcelo’s murder. Once shy about public speaking, he now does so in memory of his brother. He said he is frustrated by the pace of change and the discourse at community meetings hosted by federal monitors, which he regularly attends.

“We listen to them, and you know, they listen to us,” he said. “But I don’t see it that way really. They don’t listen to us. Every time it’s like, ‘We are looking into it, we are going to find out.’”

‘If community members are afraid to go to the police because they feel that immigration could end up being informed, that is going to affect their ability to report cases to the police.’ – Nadia Marin-Molina, advocate

One longtime Hispanic advocate, Nadia Marin-Molina, who organized day laborers in the early 2000s, said it’s “disappointing” to see some of the same issues being debated, intensified by the federal government’s aggressive campaign against illegal immigration.

“If community members are afraid to go to the police because they feel that immigration could end up being informed, that is going to affect their ability to report cases to the police. All of these things are connected,” said Marin-Molina, now associate director of the New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health. She said, as a result, a “difficult climate” remains concerning interactions with police “for the immigrant community in general.”

Focus on MS-13

By 2016, a convulsion of MS-13 violence wracked Suffolk County. First, there were disappearances, which attracted little public attention. Three Hispanic youths, all teenagers from Brentwood, went missing in February, April and June. Then came the double murder that turned all sights on MS-13.

The murders of 15-year-old Kayla Cuevas and 16-year-old Nisa Mickens, whose mutilated bodies were found in Brentwood in September 2016, became national news and galvanized the police department to crack down on MS-13. The killings, by machete and baseball bat, jolted the public consciousness.

Sini said police waged an all-out effort, assigning officers to specific gang members, who were targeted for arrest and for whatever intelligence they could provide.

“We are coming for you,” he declared at a news conference in March 2017 in Brentwood, where he stood in front of five rows of uniformed cops and recruits, a police helicopter, an armored SWAT vehicle and K-9 unit dogs.

The next month, police found the mutilated bodies of four young Hispanic males, ranging in age from 16 to 20, in a park opposite the Central Islip Recreational Center. They all had been murdered the day before, according to police. Their bodies were found after gang members sent text messages to their families.

Law enforcement agencies at every level struck back. Since then, 235 alleged MS-13 gang members have been arrested. More than 20 have been indicted on racketeering charges, including conspiracy to commit murder.

Progress, but issues remain

Today, the MS-13 gang graffiti once so apparent in Brentwood and Central Islip has been painted over. Children can be seen outside playing in the evening, and the schools have quieted. Police figures show crime down by 20 percent to 30 percent.

“In my opinion, it’s a great thing that they’re taking all these people out,” said Elkin Lorenzo, of Huntington Station.

Cuevas’ mother, the late Evelyn Rodriguez, said in an interview shortly before her death in September that police are looked at in a far more favorable way today. Residents “know they’re being heard,” she said.

But such sentiments are tempered by complaints reminiscent of those from the Lucero era.

Carlota Moran, the mother of one victim murdered in a machete attack, told the nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica in a story that ran in Newsday that police said her son, Miguel Moran, 15, had probably gone into New York City with friends and not to worry. The mother also said it was her daughter, not police, who discovered text messages that suggested Miguel had been lured into the woods on the night he was killed.

Hart said, as a mother, she sympathized with Carlota Moran’s anguish and said the department began an extensive investigation into Miguel’s disappearance immediately after he was reported missing.

Several other families of murdered children have complained of police indifference and callousness, raising questions about whether a more aggressive response to those cases could have prevented some of the gang’s later violence.

A former Salvadoran police officer said in an interview with Newsday that his missing daughter was grilled by a detective as if she were a gang associate, not a crime victim, when she was found disheveled and disoriented by the railroad tracks in Brentwood after what he described as "two or three" days of captivity by an MS-13 clique. The father secretly recorded a video, obtained by ProPublica, of the detective telling the teen, “You think we’re as dumb as the kids you hang out with? You think this is all a joke?”

Hart and Cameron said they opened an investigation immediately after the nine-minute video was posted online. They said they are trying to obtain the entire video, which is more than an hour and was made in 2016, but have not gotten it yet.

According to a Justice Department report, a Latino mother complained that she was kept waiting three hours when she came with her 8-year-old son to report that he was sexually molested. Police officials said the time it takes to get an appropriate investigator on a case can vary.

In other Newsday interviews, three young men from Bay Shore alleged they were beaten by cops in January 2018 — but never charged with a crime — after they tried to outrun a car that turned out to be an undercover vehicle, called 911 for help and were surrounded by patrol cars.

The young men — Angel Rivera, 19, and his friends, Yan Simas, 21, and Mario Vitagliano, 19 — said two cops, shouting racial epithets, punched Simas and Rivera, and a third yanked Vitagliano out of the car, handcuffed him and slammed his head onto the ice.

Then police searched the car and found nothing and let them go. They said were never told why they were stopped.

‘You teach your kid to do everything right and he does, and then the police abuse him when he’s doing nothing wrong.’ – Tina Rosario, mother of a teen who said he was beaten by police

Like Rodriguez, Rivera’s mother, Tina Rosario, was a supporter of police, but she said she remains traumatized by the incident and has filed a notice of claim signaling her intent to sue the department.

“You teach your kid to do everything right and he does, and then the police abuse him when he’s doing nothing wrong,” she said.

Since the incident, Rivera said he has been questioned twice by police — once when they pulled him over as he was driving and another time when he had been sitting in his car in a McDonald’s parking lot — without being charged with anything.

Hart said the department had opened an internal investigation into the January 2018 incident but said she could not comment on it because it is still open.

Federal changes

Since Marcelo Lucero’s death 10 years ago, the Department of Justice has been the most prominent and persistent prod for change in the Suffolk police force.

And despite the tough criticism they have often received, Suffolk police officials say the Justice Department monitoring has been good for the department.

But Trump administration officials see agreements like Suffolk’s differently.

U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, in a February 2017 speech to the national attorneys-general association, said that they hurt departments’ crime fighting and that the government would back away from using them.

“We need, so far as we can, in my view, to help police departments get better, not diminish their effectiveness,” he said. “I’m afraid we’ve done some of that. So we’re going to try to pull back on this, and I don’t think it’s wrong or mean or insensitive to civil rights or human rights.”

Lopez, the ex-Justice Department civil rights lawyer who is now a visiting law professor at Georgetown University, said she’s spoken with former colleagues at the Justice Department, and, “Everyone feels they have had the rug pulled out from under them.”

She added, “If you are going to go through the entire process of a federal investigation and a settlement agreement, you want to fix the culture.”

Those issues aside, Joselo Lucero said he knows what he sees on the street. “If something is working,” he said, “don’t you think we would have more cooperation with the regular people approaching the police?”

In Queens, he said, some police actually give residents their personal cellphone numbers and residents use them.

“You have that here?” he said. “I don’t think so.”

With Michael O’Keeffe and Stefanie Dazio

Part 1:

Part 1: Part 2:

Part 2: Part 3:

Part 3: Read More

Read More