Inside internal affairs 2-year investigation into Nassau, Suffolk police uncovered little accountability in 4 deaths, 4 serious injuries

Nassau and Suffolk police imposed little or no discipline in six cases, failed to act against some officers in a seventh, and shielded six officers from possible criminal charges.

The toll uncovered by Newsday’s Inside Internal Affairs project: four people dead and four people seriously injured — their loved ones and the wounded left to live with a shared sense of betrayal.

They are haunted by knowing that actions or inactions by members of Long Island’s two major police forces led to the deaths and injuries:

A homicidal former boyfriend tortured and stabbed to death 24-year-old Jo’Anna Bird after Nassau County police failed to respond to Bird’s repeated calls for protection.

Suffolk Officer Michael Althouse dropped Peter Fedden at home after Fedden had driven a car off a road at an estimated 100 mph, crossed lawns, broke through fences, and hit a car in a driveway. Fedden’s blood-alcohol level was almost twice the legal limit for driving. He got his mother’s car and, again driving at an estimated 100 mph, crashed into a brick building and died.

Two mentally impaired men, Daniel McDonnell and Dainell Simmons, stopped breathing after separate struggles with Suffolk County officers. The officers had provoked both confrontations when trying to take each to a hospital.

Daniel McDonnell and Dainell Simmons in undated photos. Credit: McDonnell family, Simmons family

Two-year-old Riordan Cavooris suffered lasting brain injuries when off-duty Suffolk Officer David Mascarella drove a pickup at an estimated speed of 50 mph into the Cavooris’ family car. Fellow officers shielded him from alcohol testing.

Suffolk Officer Mark Pav fabricated prisoner log entries, making it appear that he had observed the well-being of a female detainee in an open precinct holding area at a time when his partner was sexually assaulting her inside an isolated interview room.

Nassau Officer Anthony DiLeonardo shot and wounded cabdriver Thomas Moroughan in a fit of road rage after a night of dining and drinking in Suffolk County establishments. Suffolk police wrongfully arrested Moroughan.

Off-duty Suffolk Officer Weldon Drayton Jr. drank, drove and crashed into a car driven by 22-year-old Julius Scott. Scott suffered a lasting brain injury.

The loved ones and the injured are also haunted by knowing that the Nassau and Suffolk police departments imposed little or no discipline on officers in six of the eight cases, failed to act against some officers in a seventh, and shielded six officers, including Mascarella, from possible criminal charges.

Mascarella refused to submit to a breath test for alcohol three hours after he rear-ended the Cavooris family car, fracturing 2-year-old Riordan’s skull. Police failed to seek a warrant to test his blood, blocking a drunken-driving investigation and possibly a charge of assaulting Riordan.

Almost two years after the crash, Riordan walks with a leg brace and can’t run or jump.

“There are things we should know that are being withheld from us,” Riordan’s father, Kevin Cavooris, said. “We want to forgive, and we want to live in the moment and not dwell in the past, but it’s impossible to move on until we get the answers that some people have and are not telling us.”

He added: “Riordan deserves answers.”

Suffolk Police Commissioner Rodney K. Harrison has suspended Mascarella without pay and is moving to fire him, a spokeswoman said.

Simmons, who was severely autistic and nonverbal, resisted being detained by the officers who came to his group home to take him to the hospital. After they handcuffed him behind his back, they pinned him to the floor for an estimated nine minutes before he stopped wordlessly wailing and his body went limp.

“No one had one day off. No one was suspended for a half a second. Business as usual,” said his mother, Glynice Simmons. “It’s the family that’s left to pick up the pieces.”

More than a decade of discoveries

By piercing the secrecy that cloaks police discipline on Long Island, the Newsday Inside Internal Affairs project brought to light the disciplinary results of the eight internal affairs investigations — as well as the hidden actions behind them.

To date, the counties have paid $14.8 million to settle lawsuits brought by some of the victims or their survivors. Nassau paid Bird’s family $7.7 million and Moroughan $2 million. Suffolk paid Moroughan an additional $1 million and paid McDonnell’s family $2.25 million, Simmons’ family $1.85 million and Fedden’s $1,500. The suit filed by the sexual assault survivor is pending.

The patterns started with the earliest case history in 2009 and continued into 2022. The events occurred during the administrations of five Suffolk police commissioners.

Based on Newsday’s information, former prosecutors said officers’ conduct in six cases may have been grounds not just for discipline but also for criminal charges, including criminally negligent homicide, assault with a gun, assault with a car, drunken driving, official misconduct and filing a false document.

Former prosecutors also said the investigations into the deaths of McDonnell and Simmons by Suffolk detectives and the district attorney’s office appear to have been designed to clear officers of possible wrongdoing.

‘In both cases, it was clear that the intent was to protect the officers involved, and that, to me, subverts justice.’

Melba Pearson, director of prosecution projects for Florida International University’s Gordon Institute for Public PolicyCredit: Bryan Cereijo

“In both cases, it was clear that the intent was to protect the officers involved, and that, to me, subverts justice,” said Melba Pearson, who served for 16 years as a prosecutor in Miami-Dade County, Florida.

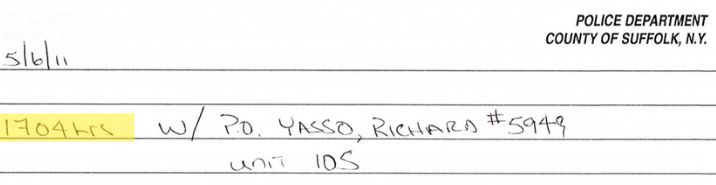

“The big commonality is you’ve got the police investigating themselves, and I think both of these situations are prime examples about why that’s not a best practice,” said Fred Klein, a Hofstra Law School assistant professor and former chief of the major offenses bureau of the Nassau County DA’s office.

In four cases, officials of Nassau and Suffolk Police Benevolent Associations helped protect officers from investigations or punishment.

At the highest level, former Commissioner Lawrence Mulvey told Newsday that the Nassau PBA exerted political muscle on then-County Executive Edward Mangano to reduce the discipline imposed on officers who failed to protect Bird from the ex-boyfriend who killed her.

“The PBA thought the discipline I had in mind [plea offers] was too harsh and behind the scenes they had Mangano’s ear. The process of negotiating plea agreements lingered and dragged on until I retired,” Mulvey wrote in an email, adding that his frustrations sped up his decision to retire.

Mulvey said he had wanted to suspend some officers for four months. Newsday confirmed that the department substantiated charges against 14 officers and limited punishment to loss of as little as four hours of sick and vacation time to a high of 24 days of accrued sick and vacation time.

In an interview, former Nassau PBA President James Carver denied negotiating discipline with Mangano. Imprisoned in connection with a bribery scheme, Mangano declined to comment through his attorney.

Five of the officers investigated for their actions leading up to Bird’s killing have been promoted. Two are now president and financial secretary of the PBA. The IA report shows no indication that internal affairs held top commanders accountable.

More overtly, Suffolk PBA delegates drove two officers — Mascarella and Drayton — away from the scenes of the car crashes that injured Riordan Cavooris and Scott, in effect buying time for any possible alcohol in the officers’ systems to dissipate.

As happened with Mascarella, Drayton later refused a breath test and escaped an arrest with the potential for a court-ordered blood test. His punishment was the loss of four days of accrued time off.

‘My life was worth four sick days?’

Julius ScottScott was left unable to focus because of brain injuries and could not work for more than four years. He learned for the first time about Drayton’s punishment through Newsday.

“My life was worth four sick days?” he said in response.

In the road rage case, a high-ranking member of the Suffolk police brass directed the department’s internal affairs commander to remove from a report evidence that supported misconduct charges against two sergeants responsible for investigating the shooting of cabbie Moroughan.

The commander told Newsday that he refused and believes his stance prompted a transfer out of IA.

While internal affairs scrutinized the case, the lead IA sergeant won election as a trustee of the Superior Officers Association, the union representing sergeants. She recommended no charges against the two sergeants.

Suffolk internal affairs missed an 18-month deadline for filing charges against officers in three cases, exempting them from discipline in Moroughan’s wrongful arrest, the death of McDonnell and the filing of a false document by Pav, the partner of the officer who sexually assaulted a woman inside the precinct and was sentenced to a year in federal prison.

‘I was in a precinct. I couldn’t trust anybody. It was horrible.’

Sexual assault survivor“I was in a precinct. I couldn’t trust anybody. It was horrible,” the woman recalled, breaking into tears. “I should have been able to have at least one person that I could have depended on, and I couldn’t.”

Asked about Pav’s escape from discipline, the woman said that punishing him — as well as his supervisors and other officers who refused her request to go to a hospital — would have forced a look at the responsibility of “everyone that was in the precinct in that shift.”

“If they held more than one officer accountable for this, they’d have to admit that it was them,” she said.

A contract clause negotiated by the PBA blocked the SCPD from firing an officer: Althouse, who dropped Fedden off at home after a 100-mph crash.

The department charged Althouse with misconduct for failing to perform sobriety testing on Peter Fedden after the first of Fedden’s crashes.

Fedden, a deli owner, was a favorite of officers because he provided them meals for next to nothing. Without notifying a dispatcher that he was transporting a civilian, as required by regulations, Althouse drove Fedden home from the crash. Within minutes, Fedden crashed again at 100 mph, this time fatally at the wheel of his mother’s car.

An autopsy showed that Fedden’s blood-alcohol level was twice the legal limit for driving.

Facing potential termination by the police commissioner, Althouse shifted his case to an arbitrator, as allowed by the union contract.

Police regulations required Althouse to perform sobriety testing. Still, the arbitrator dismissed the misconduct charge, citing Althouse’s statement that he saw no evidence Fedden was drunk. The arbitrator limited the department to counseling Althouse about the need to notify a dispatcher before transporting a civilian.

Internal affairs secrets

The Nassau and Suffolk police departments kept the outcomes of internal affairs investigations secret even from the victims of alleged police misconduct.

One example: More than a decade after Leonardo Valdez-Cruz fatally stabbed Jo’Anna Bird, Newsday informed the family about the contents of a 781-page internal affairs report about police failures to protect Bird.

“I wanted them to open up the internal affairs report because I never got a chance to see it,” said Bird’s mother, Sharon Dorsett. “And I feel that me being her mother and everything she went through, and we went through, I had the right to see it, as her mother, to know what was in it.”

‘I feel that me being her mother…I had the right to see [the Internal Affairs report].’

Sharon Dorsett, mother of Jo’Anna BirdCredit: Newsday/Jeffrey Basinger

The Inside Internal Affairs project has been the product of a two-year investigation. The time and effort were necessary because the Nassau and Suffolk police departments asserted that most police disciplinary records are, by law, sealed from public view.

The departments maintained their stances despite the repeal in 2020 of a half-century-old law, known as 50-a, that barred release of the documents. The state legislature and then-Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo acted after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

When Newsday requested access to officers’ disciplinary records under the state Freedom of Information Law, Nassau Police Commissioner Patrick Ryder responded that state law still kept the majority of the documents secret — whether or not internal affairs had substantiated charges against an officer.

The Suffolk Department, led initially by Geraldine Hart and now by Harrison, agreed to release records relating only to substantiated charges — limiting Newsday’s view into its internal affairs process to only two cases.

The department partially redacted the documents and delayed providing them for as long as 18 months.

Newsday is pressing lawsuits against both departments with the goal of establishing that the public has a right to review how Long Island’s police forces police themselves.

Denied internal affairs records, Inside Internal Affairs reporters built case histories by delving into court cases that alleged misconduct by Nassau and Suffolk officers, seeking documents from the families of people who had been killed or injured, obtaining documents through those with knowledge of the cases and filing public record requests with agencies independent of the police departments.

In one instance, USA Today asked the Nassau County District Attorney’s Office for seemingly unrelated records. The response included a 781-page internal affairs report about Jo’Anna Bird’s death.

Newsday had long sought the document, including through court actions. In contrast to the police department, the district attorney’s office stated that the law mandated the report’s release.

USA Today partnered with Newsday. Each produced its own report about the case.

The former commander of the Suffolk County Police Department’s Internal Affairs Bureau spoke for the first time publicly about his tenure in IA. He said that he was ordered to reform the unit but was then denied enough staff to sufficiently investigate cases.

Former Suffolk Insp. Michael Caldarelli also said he met resistance after substantiating misconduct findings in an investigation of McDonnell’s death, as well as in the Moroughan case.

‘There are people who seem to feel that internal affairs should be functioning as an organ of defense…By definition, that’s corruption.’

Michael CaldarelliCredit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

“It’s clear to me there are people who seem to feel that internal affairs should be functioning as an organ of defense,” he said. “It cannot be that way. By definition, that’s corruption.”

Newsday sought to interview each of the officers named in the Inside Internal Affairs project, including by telephone, email and letters. Several declined to comment on the record when reached directly. The majority did not respond. Attorneys for some of the officers issued statements defending their conduct. Those statements, included here, were made for the stories’ original publication, as were the comments of experts, victims and loved ones.

Ryder declined interview requests. Harrison, who took over the department this year, declined, or did not respond to, interview requests. He issued brief written statements about the cases in which Officers Drayton and Mascarella refused to take breath tests after driving crashes. Those statements are reflected later in this story.

Flawed investigations protect officers

The Inside Internal Affairs project gathered perspectives on the police actions detailed by the case histories from a cumulative total of 40 experts in criminal law, police and correction procedures, police discipline, mental health and alcohol enforcement.

These experts included former prosecutors, former police officers, commanders and detectives, criminal defense lawyers, former leaders of correction systems, a judge who monitored a police disciplinary system, psychiatrists and the chief health officer of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. Almost half of the experts taught about their fields at colleges or universities.

Those with law enforcement backgrounds evaluated Newsday’s case histories based on how thoroughly police and prosecutors conducted investigations and on whether evidence suggested disciplinary or criminal charges may have been warranted against officers.

Pearson, the former Miami-Dade County prosecutor, said a full police and grand jury investigation had the potential to support criminally negligent homicide charges stemming from Simmons’ death. She cited the fact that officers pinned him to the floor in a partially prone position that risked suffocation for nine minutes.

“You have a situation here where the person was nonverbal and could not beg for their life. So, all he could do was push and twist and pull,” she said, adding that “officers are trained: They’re only supposed to leave people in that position for short amounts of time because of the fact that they’re not able to breathe.”

Klein, the former Nassau assistant district attorney, said the information did not indicate that the officers had been grossly negligent, a necessity for a criminal charge.

“Here, you’ve got police officers who were doing their jobs, maybe not in the best way possible, maybe with a lack of training, but they’re doing their jobs,” he said, adding, “Given the nature of these struggles where it’s second by second, you don’t have a lot of time to think about it, it’s very hard to make out that a police officer doing their job in a struggle, which is basically justified, is grossly deviating from what a reasonable person would do.”

Instead, Klein saw the possibility of holding a Suffolk sergeant criminally responsible for failing to give McDonnell, who suffered a psychiatric episode in a police holding cell, the medications he relied on to control bipolar disorder. Suffolk police regulations required officers to help a prisoner obtain medications and to verify prescriptions, or to transport the prisoner to a hospital.

Police arrested McDonnell on a misdemeanor charge. His mother brought two CVS pill bottles with damaged labels to the precinct. The sergeant chose not to dispense the medications, did not log that he had received them, and did not send McDonnell to a hospital.

Detainees in nearby cells wrote in sworn statements that McDonnell pleaded for the medications. In the morning, McDonnell stripped naked and stuffed the toilet in his cell with clothing.

A lieutenant testified that he was concerned McDonnell could attempt suicide. He ordered officers to remove McDonnell from the cell for transportation to a hospital — generating a struggle that proved fatal.

“There’s no reason why the desk sergeant couldn’t call CVS and say, ‘Did you prescribe this medication for this man?’ and provide it to him. I mean, the cops are supposed to protect and serve and not ignore and neglect,” Klein said. “To me, if there’s any criminality in that encounter, it was that. Maybe official misconduct, maybe reckless endangerment on the part of the sergeant.”

Pearson and Klein both said the evidence as collected did not show grounds for criminally charging the officers who subdued McDonnell.

Still, law enforcement experts described the police homicide investigation into whether officers were criminally responsible for McDonnell’s death in terms such as “a sham” and “cursory.”

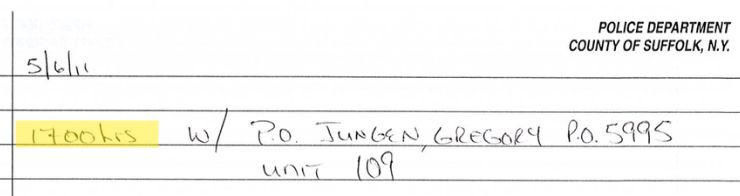

Homicide Det. Ronald Leli led the investigation. He interviewed the officers who struggled with McDonnell at the precinct, often in the presence of an attorney affiliated with the Suffolk County Police Benevolent Association.

Leli’s notes show that he completed interviews with 11 of the officers in a total of 50 minutes, finishing one in two minutes, according to his notes. Often, he wrote only that the officers had confirmed the accuracy of their written reports, referred to as supplemental or “supp” reports, and had given him copies.

According to his notes, for example, Leli interviewed one officer starting at 5 p.m. His notes read in full: “Supp reflects incident. Supp turned over.”

Four minutes later, according to the notes, Leli started to interview a different officer. The notes read: “Supp reflects incident. Supp turned over.”

5 p.m.: Leli recorded interview start.Detective notes

5:04 p.m: Leli recorded next interview start.Detective notes

A sergeant’s interview extended for half an hour, the sergeant estimated in testimony. He testified that detectives never asked about the force used to subdue McDonnell.

In his case report, Leli encapsulated the fatal struggle in three sentences.

Commenting on the notes showing that many of the detectives’ interviews lasted just minutes, Gary Raney, a former Idaho sheriff, said:

“What I saw was indicative that this investigation was probably a sham. Simply, if you compared it against a homicide investigation where the potential suspect was not a law enforcement officer, you would never see an interview in a criminal case that only lasted two minutes for somebody who was directly involved in the potential cause of death. That is just unheard of.”

He added in an email: “The criminal investigation violated generally accepted investigative practices and shows a bias to absolve the officers.”

The investigation was ‘very lacking and cursory.’

Ayanna Sorett, former assistant Manhattan district attorneyCredit: Newsday/Jeffrey Basinger via Zoom

Ayanna Sorett, who served for 15 years as an assistant Manhattan district attorney, called the investigation “very lacking and cursory.”

“There certainly was enough that warranted a thorough and full investigation,” said Sorett, who spoke to Newsday before her appointment to a position in New York City Mayor Eric Adams’ administration. “And I can definitely see bringing this before a grand jury after a thorough and full investigation” to determine potential criminal charges.

Thomas Spota, then the Suffolk district attorney, failed to conduct a grand jury investigation into McDonnell’s death, leaving as a last word Det. Leli’s finding that there had been no criminality.

Klein said: “Why wouldn’t you let the members of the public [on a grand jury] determine if crimes are committed, make that decision as to whether the negligence rose to the level of criminality? Why does the homicide detective get to make that decision? To me, that’s just not the way to be running a homicide investigation.”

Spota’s office did put the Simmons case before a grand jury, but the experts who viewed summaries of lawsuit testimony compiled by Newsday and an interview of one witness concluded that the presentation appeared geared to return no indictment against the officers.

Most prominently, they noted that the district attorney’s office did not call before the grand jury the medical examiner who performed Simmons’ autopsy and had concluded that chest compression had contributed to his death.

‘It may very well be a smoking gun showing that this case was presented with the idea of not obtaining an indictment.’

Fred Klein, former chief of the major offenses bureau of the Nassau DA’s officeCredit: Newsday/John Paraskevas

When the grand jury took testimony, Dr. Maura DeJoseph had taken a new job in Connecticut. Testifying in the family’s lawsuit, she said that she was not asked to appear before the panel.

Instead, the district attorney’s office called Dr. Michael Caplan, the county’s chief medical examiner, who did not work in Suffolk at the time of Simmons’ death, did not participate in the autopsy and had not consulted with DeJoseph about her findings.

The lead police investigator, Det. Sgt. Edward Fandrey, testified that Caplan was “more aligned” with Fandrey in believing Simmons’ own physical exertion had caused him to die.

Speaking about the DA’s failure to call DeJoseph, Klein said, “It may very well be a smoking gun showing that this case was presented with the idea of not obtaining an indictment.”

Officers refuse blood-alcohol tests

A security camera captured the crash that fractured Riordan’s skull. Credit: St. James Star via SCPD

A full investigation of the crash injury that fractured 2-year-old Riordan Cavooris’ skull into puzzle-like pieces may have resulted in charging Mascarella with drunken driving and assault for causing a serious injury by allegedly driving while intoxicated, the experts said.

A sergeant at the scene and precinct officers failed to ask Mascarella to submit to a preliminary breath test, known as a PBT. The test entails breathing into a cellphone-sized device that produces an approximate alcohol reading.

After a detective told a sergeant that he wanted Mascarella to undergo a PBT, the sergeant notified a Suffolk County Police Benevolent Association delegate, who drove Mascarella away from investigators to South Shore University Hospital, 15 miles away.

At the hospital, Officer Kevin Wustenhoff falsely reported to a supervisor that he had given Mascarella the PBT and that Mascarella had passed it, according to a law enforcement source with knowledge of the case. Wustenhoff then retracted the account, the source said.

Three hours after the crash, Deputy Insp. Mark Fisher asked Mascarella to take a PBT. Mascarella refused.

When drivers say no to a PBT, police typically take them into custody for more sophisticated testing, including asking a judge to issue a warrant for blood testing. Fisher issued a traffic ticket to Mascarella.

Police failed to notify the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office on the night of the crash that an officer had been involved in an unexplained, high-speed, rear-end crash, had seriously injured a 2-year-old and had refused a breath test. The omission prevented the DA from considering whether to seek a warrant to test Mascarella’s blood, ruling out a possible vehicular assault prosecution.

“I know based on what I have seen, they did not do a diligent, reasonable, defensible investigation,” said John Bandler, a former state trooper who served as a prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office for 13 years.

‘They did not do a diligent, reasonable, defensible investigation.’

Former state trooper and prosecutor John BandlerCredit: Newsday/Reece T. Williams

In addition to suspending Mascarella without pay, Harrison suspended Wustenhoff without pay for 45 days. The department permitted him to stay on the payroll until 2025, when he will be eligible to retire with a 50% pension that he could begin collecting immediately. He was paid $176,177 in 2021.

Mascarella’s lawyer, William Petrillo, asserted that the DA’s investigation “correctly concluded that no crime was committed.” He stated that “alcohol was not a factor” in the crash.

Wustenhoff’s lawyer, Anthony LaPinta, called the account that Wustenhoff falsely reported that Mascarella had passed a PBT “incorrect.”

In an email, Harrison stated that he is establishing policies aimed at preventing police from giving special treatment to off-duty officers. He declined to comment on the specifics of the case. A spokesperson wrote that Harrison is moving to terminate Mascarella.

Former DA Timothy Sini and his successor, Ray Tierney, wrote in emailed statements that the police investigation failed to collect the evidence necessary to determine whether Mascarella had been drinking.

After the crash that left Julius Scott with a lasting brain injury, a PBA delegate drove Drayton, also an off-duty Suffolk officer, away from the scene, as happened for Mascarella.

Drayton, who served as a volunteer firefighter, consumed alcohol at a charity fundraising event. A fire call came in. While racing to the scene, he crashed into a car that Scott was driving. As happened with Mascarella, he refused to submit to a PBT.

“He should have been arrested,” said Jonathan Damashek, a vehicular accident legal expert.

After a 10-month public records request push, Newsday obtained a heavily blacked-out copy of the IA report. The lead investigator, Lt. Peter Ervolina, recommended that the department substantiate a charge of conduct unbecoming against Drayton for refusing the breath test.

Drayton demanded arbitration. Four years after the crash, he accepted Ervolina’s finding with a penalty of losing four days of accrued time off.

Between the time the department filed the charge and the time that Drayton accepted the punishment, then-Commissioner Sini commended Drayton for making the most drunken driving arrests in the First Precinct.

In 2021, the police department paid Drayton $285,000, according to payroll records. Five months after Newsday published the case history, the department transferred Drayton to administrative duties. In an emailed statement, Harrison described the case as “deeply disturbing.”

Scott has been left unable to focus because of brain injuries. He could not work for more than four years and now works for Walmart. He settled a lawsuit against the Central Islip Fire Department for $180,000.

‘Cover-up of a cover-up’

DiLeonardo, the officer who shot cabdriver Moroughan in a road rage encounter, could have been charged with assault for opening fire without cause after a night of dining and drinking, the experts said.

“He should have been arrested that night,” said Philip Stinson, a former police officer and Bowling Green State University criminal justice professor.

An officer and a detective separately noticed the smell of alcohol around DiLeonardo, fellow off-duty officer Edward Bienz and their companions that night. An emergency room doctor noted the odor of alcohol on DiLeonardo at the hospital.

The lead sergeant at the scene told internal affairs that he did not subject DiLeonardo to alcohol testing because he detected no evidence that DiLeonardo had been drinking.

At the hospital, a second sergeant ordered detectives to take a statement from Moroughan while he was sedated with painkillers. They emerged from his room with a statement in which Moroughan purportedly confessed to aiming his car at DiLeonardo, giving DiLeonardo cause to open fire.

Police arrested Moroughan. Three months later, the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office, then led by Thomas Spota, asked a judge to dismiss charges against Moroughan. At the same time, Spota chose not to ask a grand jury whether DiLeonardo should be charged with assault.

Sgt. Kelly Lynch, assigned to internal affairs, investigated Moroughan’s wrongful arrest. She focused on the actions of two sergeants, the accident scene supervisor and a sergeant who ordered detectives to take Moroughan’s hospital statement.

Lynch won election as a trustee of the Superior Officers Association, the union that represents sergeants, while working in internal affairs.

She recommended filing no charges.

Caldarelli, the internal affairs commanding officer, overruled Lynch and substantiated charges against the sergeants. By then, IA had missed the 18-month charging deadline.

Still, Caldarelli wrote a report that included his findings. Then-Chief of Detectives William Madigan summoned him to a meeting. There, Caldarelli said, Madigan ordered him to remove from the report evidence that was crucial to supporting the charges.

Notations on Caldarelli’s report show that Madigan wrote “Delete” and “Out” beside key passages in the document.

“It’s a cover-up of a cover-up,” said Bennet Gershman, a Pace University Law School professor and former federal prosecutor.

In a Newsday interview, Madigan denied that he ordered Caldarelli to delete material or change his findings.

SCPD transferred Caldarelli out of IA after a two-year tenure that he described as “Kafkaesque.” The SCPD found that all charges against the sergeants were “unfounded.”

The Nassau County Police Department internal affairs unit concluded that DiLeonardo had committed 11 unlawful acts, including assault and criminal use of a firearm. The NCPD dismissed DiLeonardo.

Bienz lost 20 days of pay. He has since been promoted twice to lieutenant.

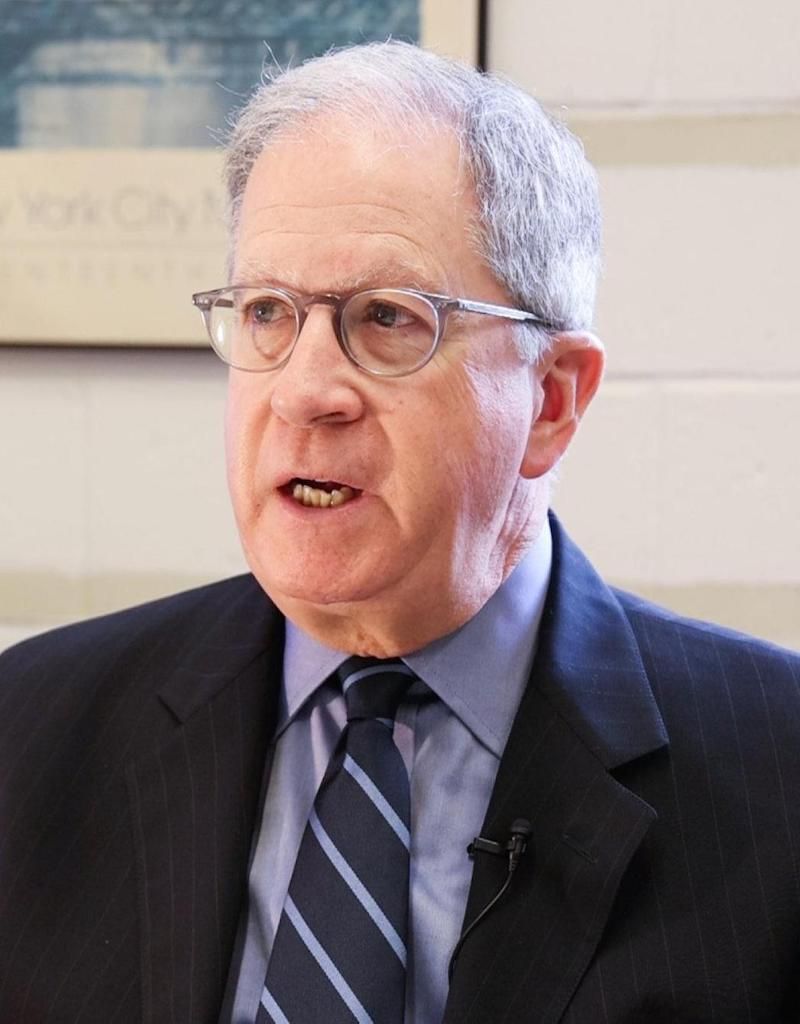

Fabricated log entries

Newsday’s case summary about events surrounding the sexual assaults inside the First Precinct prompted Cheryl Bader, a Fordham University Law School professor and former federal prosecutor, to respond that an investigation may have resulted in charging Pav, the officer who fabricated log entries, with offering a false instrument for filing, a misdemeanor.

The law “certainly can capture the conduct here because prosecutors can establish that Pav knew that the [log] was false,” Bader said, adding, “A jury would be outraged by this.”

Rebecca Roiphe, a New York Law School professor and former Manhattan assistant district attorney, said Pav’s actions appeared to violate the law but may not have warranted prosecution. A decision would really “rest on whether he’s just being an unquestioning, good friend, or whether he actually suspects that there’s something bad going on.”

Newsday obtained Internal Affairs records that show no evidence that Suffolk police considered a possible criminal charge against Pav. His lawyer, Anthony LaPinta, characterized Pav’s actions as “record-keeping mistakes” unrelated to McCoy’s crime.

Without a recorded cause, Pav and his partner, former Officer McCoy, pulled over a car as it left a parking lot in Wyandanch, a predominantly Black community. The driver and his passenger, a woman, are Black. Pav and McCoy are white.

Without cause, they asked the woman to identify herself and discovered outstanding warrants for noncriminal offenses. Pav and McCoy released the driver and brought her to the precinct, starting 24 hours in custody.

Pav left the woman alone with McCoy, who brought her to an interview room, closed the door and forced her to perform oral sex.

“My choice was to either put my life in danger and tell him, ‘No,’ or just to do it and live to tell somebody,” the woman said.

The metal table where the woman was handcuffed and the interview room where she was sexually assaulted at the First Precinct. Credit: Exhibits in federal civil rights lawsuit

A few hours later, Pav and McCoy together returned the woman to the interview room for the stated reason of asking her to help with undercover marijuana buys.

Pav left McCoy and the woman in the room. McCoy again forced her to perform oral sex. When his head turned, she spit onto her lavender sweater to collect his DNA.

Suffolk police regulations required officers to observe the well-being of prisoners at least every half-hour and to record their observations on activity logs. Pav backdated an incomplete log with nine false entries, some recording that he had observed the woman during the period when McCoy assaulted her.

The woman was convinced that she could not trust the Suffolk police to investigate her two sexual assaults.

“I couldn’t chalk this up to being like, ‘Oh this is this one guy,”’ she said. “It was to a point where it was like, ‘No, this is a system,’ like they’re leaving his man alone in this room to do what he’s doing to me.”

She turned her DNA-laden sweater over to the FBI. Agents arrested McCoy, starting the 18-month clock for filing disciplinary charges. Federal prosecutors asked internal affairs to delay a disciplinary investigation while their criminal investigation of McCoy was underway.

Federal prosecutors charged McCoy with a single count of depriving the woman of her civil rights. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to a year in prison.

While concluding that Pav had violated four departmental rules and procedures, IAB absolved him of more serious misconduct — characterizing the prisoner log fabrications as “neglected … timely arrest log entries” — and missed an 18-month deadline for filing charges that can lead to discipline.

He received only counseling.

A supervisor concluded that Pav could be an asset to the department by showing “how precarious it can be to unnecessarily deviate from routine procedures.”

The woman believes that Suffolk police evaded holding a wider circle of officers accountable, including supervisors.

“Everyone’s walking past this room, this guy’s in here with this woman by himself for extended periods of time, and he keeps bringing her back there,” she said. “No one’s looking at that. They’re comfortable for a reason. This is a group effort.”

MORE COVERAGE

Reporters: Paul LaRocco, Sandra Peddie, David M. Schwartz

Editors: Arthur Browne, Keith Herbert

Photo and video: Jeffrey Basinger, James Carbone, Bryan Cereijo, Joseph D. Sullivan, John Paraskevas, Alejandra Villa Loarca, Heather Walsh, Reece T. Williams

Senior multimedia producer and video editor: Jeffrey Basinger

Script production: Jeffrey Basinger, Arthur Browne, Keith Herbert, Robert Cassidy, Paul LaRocco, Sandra Peddie, David M. Schwartz

Photo editor: John Keating

Digital project manager and producer: Heather Doyle

Digital design/UX: James Stewart

Social media editors: Gabriella Vukelić, Priscila Korb

Print design: Jessica Asbury

QA: Sumeet Kaur