Grumman's corporate headquarters in Bethpage in January 1984. Photo credit: Newsday / Robert Gurecki

The year 1976 looms large in the decadeslong saga of the massive toxic plume beneath Bethpage.

That June, Grumman Aerospace not only received a confidential assessment that groundwater contamination was spreading from its sprawling facility, but options on how to tackle the budding crisis.

It chose the least aggressive approach, short of one labeled “Do Nothing.”

When the problem finally emerged publicly, the company continued withholding critical information and maintaining it wasn’t culpable. Today the pollution threatens water supplies for a quarter-million residents of southeastern Nassau County.

Grumman, then Long Island’s biggest employer and a political power, got plenty of help. Throughout 1976, state and local regulators minimized the hazards at the 600-acre site even while advising Grumman to switch its drinking water supply to public wells. And for years after that, the officials falsely blamed another manufacturer for the bulk of the contamination.

This pattern continued into 1990, after proof of Grumman’s responsibility became unavoidable. It was so well established that two federal judges ruled in recent years that Grumman should have informed its insurers of it earlier and that, partly as a result, the insurers wouldn’t have to cover liabilities from the environmental debacle.

If you’re going to do the minimum you have to do to be in compliance, you get a four-mile-long and two-mile-wide plume.

Richard Humann, president and CEO of H2M architects + engineers of Melville

In 2014, U.S. District Court Judge Katherine B. Forrest relied on internal corporate documents, including the June 1976 confidential assessment from Grumman’s consultant that showed the depth of the company’s knowledge and role.

Just last September, a second district court judge, Lorna G. Schofield, focused even more on the consultant memo as she ruled that the insurers wouldn’t have to cover claims in a newer class-action lawsuit by residents who blame health ailments on the contamination.

“The company’s notice obligation arose by June 1976,” Schofield wrote. “By that time, Grumman knew from regulator and consultant reports that the groundwater was contaminated, Grumman was a likely source of contamination, the contamination could pose health risks, Grumman should look for an alternative drinking water supply other than the facility wells, and finally [that] even aggressive remedial measures may not wholly abate the contamination.”

As consequential as this behavior was for the insurer, it was all the more so for Bethpage and surrounding communities. Years were lost while the plume, and health fears from it, grew.

Northrop Grumman declined multiple Newsday requests for interviews. In the first insurance case, however, it said Grumman not only believed that the other manufacturer was to blame, but that after testing conducted between 1977 and 1980, “regulators believed that no additional investigation of the Bethpage facility was warranted.”

Forrest and Schofield both said any thought that Grumman believed at the time that another company was the cause of the pollution was “unreasonable,” with Schofield further noting that regulators “consistently identified Grumman as a source.”

Since beginning its cleanup efforts, Northrop Grumman says it has spent more than $200 million. Its efforts have largely focused on pollution containment systems on its original properties. That has left local taxpayers and the U.S. Navy — which owned a sixth of Grumman’s site — to pay for most of the public supply treatments that have been installed over the last 25 years.

“If you’re going to do the minimum you have to do to be in compliance, you get a four-mile-long and two-mile-wide plume,” said Richard Humann, president and CEO of H2M architects + engineers of Melville, the Bethpage Water District’s longtime environmental consultant.

Four options

The stage was set for the critical events of 1976 in the waning days of the year before.

That November, the Nassau County Health Department completed a two-year study on contamination of some of Grumman’s 13 private water wells, a probe that began after complaints from employees about taste and odor problems in the drinking water. The company, in response, had shut several of the wells.

Despite information that pointed to Grumman as a significant cause, the county focused its report on the Hooker Chemical Co. of Hicksville. Hooker abutted Grumman and produced the carcinogenic compound vinyl chloride, which state tests measured in Grumman’s wells at as much as 50 parts per billion.

Mentioned several pages into the report was the discovery of another carcinogen, trichloroethylene, or TCE, a degreaser used by Grumman for decades. In one well its presence reached 500 parts per billion. TCE is now the most prevalent of two dozen plume contaminants.

The health department’s findings weren’t publicly released, but at the department’s request, Grumman tasked Geraghty & Miller, an environmental consulting firm, to assess the problem.

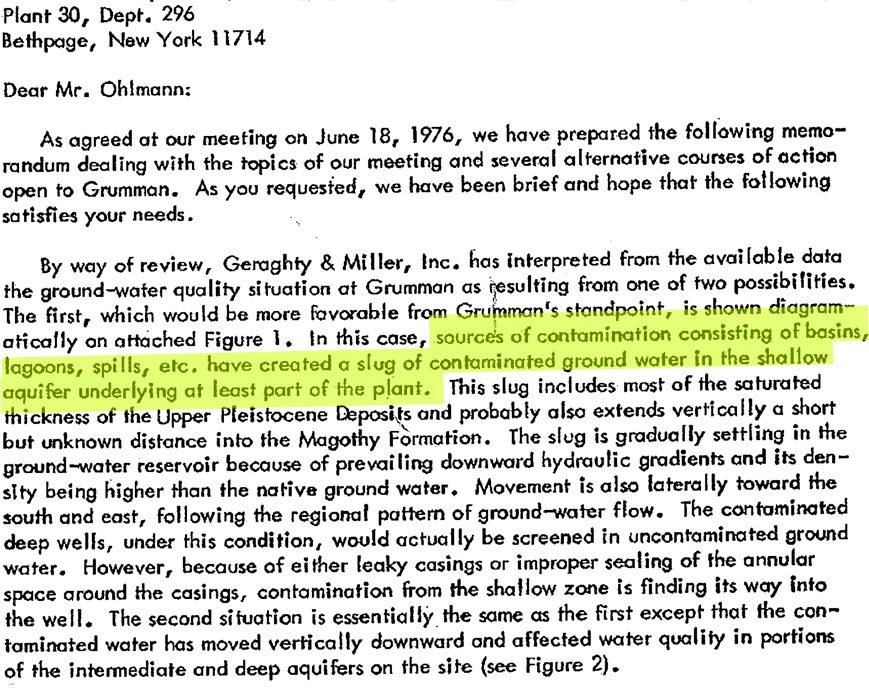

In June 1976, the firm produced the confidential memo, central to the two insurance suits, that tracked the contamination’s significance. It was one of several documents submitted in the first case that was supposed to be sealed and kept secret but that Newsday discovered were not.

To start, the consultant found on Grumman’s property “sources of contamination consisting of basins, lagoons, spills, etc.” While not explicitly naming Grumman as the cause, it noted no other possibilities — and in an attached rendering depicted some of those sources as part of the company’s facility.

Geraghty & Miller warned that contamination had formed into a “slug” in the groundwater below Grumman’s plant. At minimum, it was sinking below the shallowest portion of Long Island’s aquifer — a water-filled layer of rock, gravel and sand that is its sole source of drinking water. The mass was moving toward the next deepest level of the aquifer, which provides the bulk of the Island’s drinkable water.

Most ominously, the firm wrote, “Trace concentrations of contaminants in pumped water may not be indicative of the severity of the overall problem.”

It presented four options:

- “Do Nothing,” which it noted had “no immediate cost” but risked further worsening of the water supply.

- Switch Grumman’s drinking water from its contaminated private wells to the Bethpage Water District’s, with tainted water pumped only for industrial purposes.

- Abandon contaminated wells and drill new ones, with the drawback that these “may also become contaminated in time.”

- Conduct “a ground water investigation,” which while “costly” could identify sources of contamination “so that they can be eliminated,” as well as “provide information on location, direction and rate of movement of slug of contaminated water.”

“It would be unwise for Grumman not to carry out some studies on the source and extent of the contamination,” Geraghty & Miller wrote.

Nonetheless, the report recommended, and Grumman accepted, the second option. That allowed the company to protect its 20,000 workers from drinking any more tainted water but essentially avoided the larger issue: determining the magnitude of the problem and how to fix it.

The scenario left open the risk that, untracked and unabated, the contamination could grow exponentially — as it did. The consultant predicted what that could mean with acute accuracy:

- “Slug may spread both laterally and vertically beneath the property”

- “Neighboring wells may become contaminated over the long term”

- “Further contamination may take place from sources not presently detected”

Schofield’s 2019 ruling cited the memo, as well as the county’s 1975 report, as a benchmark: “The totality of these facts shows that by June 1976, Grumman reasonably understood that it could be responsible for a ‘severe’ contamination spreading into the local water supply.”

A secret exposed

Sal Greco Jr., then a Bethpage Water District commissioner, vividly remembers the phone call he received at home on a Sunday morning in 1976 from Dean Cassell, a Grumman vice president.

“His conversation, basically, was that his employees were getting sick from drinking their water,” Greco, now 81, said recently, recalling the problems as digestive. “So, he said, ‘We have to hook up to the Bethpage water system.’”

After the county report and Geraghty & Miller’s memo, Grumman discretely started switching its private drinking water supply to Bethpage’s. The company had 13 wells, the district nine.

Cassell, now deceased, didn’t mention internal company warnings that the contamination was spreading in the aquifer, Greco said. That would have alarmed the water district.

But by mid-1976, others with more information were already showing plenty of disquiet. Nassau County, knowing the level of toxic compounds in Grumman wells, reached out to the federal Environmental Protection Agency for guidance.

In its response that August, the EPA focused less on vinyl chloride and more on the extreme levels of TCE that had been identified further down in Nassau’s 1975 report. Citing the imminent banning of the chemical in food processing, such as decaffeinated coffee, where levels averaged roughly 60 parts per billion, the agency observed that “a water supply containing 500 [parts per billion of] TCE would, on this basis, be definitely unsuited for drinking purposes.”

“… we would recommend that this water not be used for drinking purposes unless suitably treated.”

1977 Nassau County Health Department chronology of Grumman contamination See full documentGrumman, as it had for wells with elevated ammonia and nitrate levels, closed those with the worst TCE problems.

And, as before, it initially kept this action from the public.

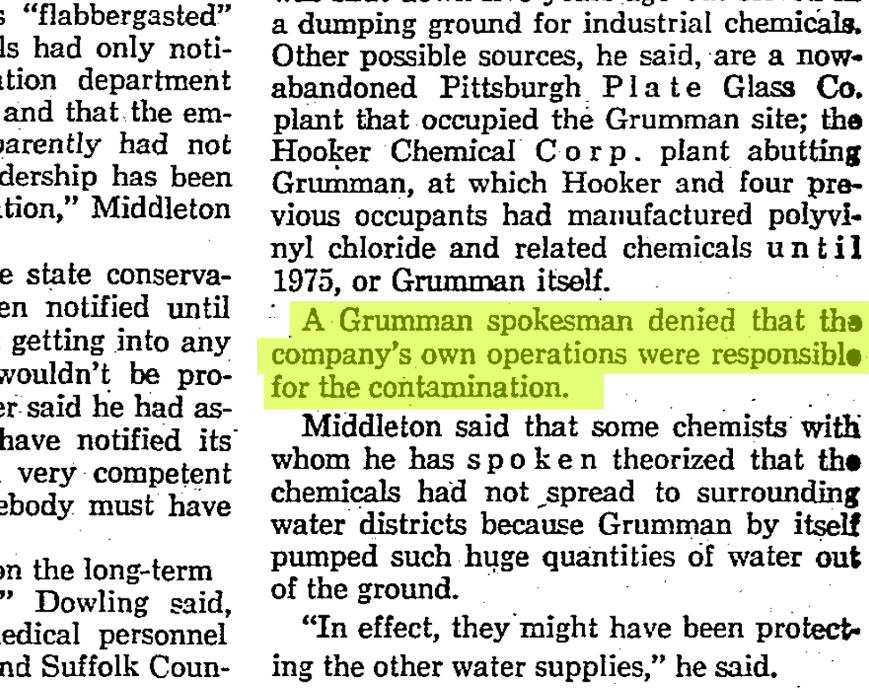

Full disclosure came three months after the EPA’s advisory, when an article in the Albany Times-Union newspaper revealed that “small amounts of the toxic chemical polyvinyl chloride have been found in some municipal and private water systems on Nassau County, Long Island.”

A day later, Newsday reported that not only did officials find polyvinyl chloride (later corrected to vinyl chloride) at Grumman, but also TCE at the 500 parts per billion level.

Newsday offered the company’s first public comment on the pollution, after a state official speculated that it could be among the possible culprits: “A Grumman spokesman denied the company’s own operations were responsible for the contamination.”

“A Grumman spokesman denied that the company’s own operations were responsible for the contamination.”

Newsday edition Nov. 28, 1976 See full article

“…sources of contamination consisting of basins, lagoons, spills, etc. have created a slug of contaminated groundwater in the shallow aquifer underlying at least part of the plant.”

1976 internal consultant memo to Grumman See full documentGrumman then posted a notice to employees that began, “Contrary to implications in the media on November 27 and 28, drinking water in the Bethpage complex has consistently met the drinking water standards under the State Public Health Law.” The causes of the concern — TCE and vinyl chloride — were not covered by the law until the next year.

The response belatedly noted the company’s abandoning of wells but didn’t mention the high TCE levels found in some.

After this initial disclosure, then-state Assemb. Lewis Yevoli (D-Old Bethpage) recalled speaking to a colleague who had been conversing in an Albany bar with state laboratory technicians. His concern was captured in stark language.

“The sample showed the water was so bad — he used their term — that he told me, you could take the paint off furniture,” said Yevoli, 81, who served in the Assembly until 1991.

He helped convene an Assembly public hearing on the contamination that found “local officials had been derelict” in protecting the water supply.

“As long as I was involved in those days, they never admitted that they caused the problem,” Yevoli said of Grumman. “It turned out to be far more serious than anyone realized.”

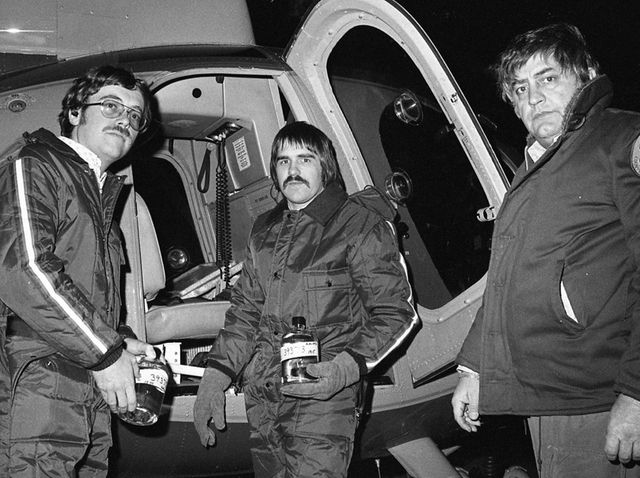

Randy Braun and Bob Cibulskis of the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s Surveillance and Analysis Division load water samples from the Grumman Corp. plant in Bethpage onto a Nassau County police helicopter piloted by Frank Madonna in December 1976. Photo credit: Newsday / Jim Peppler

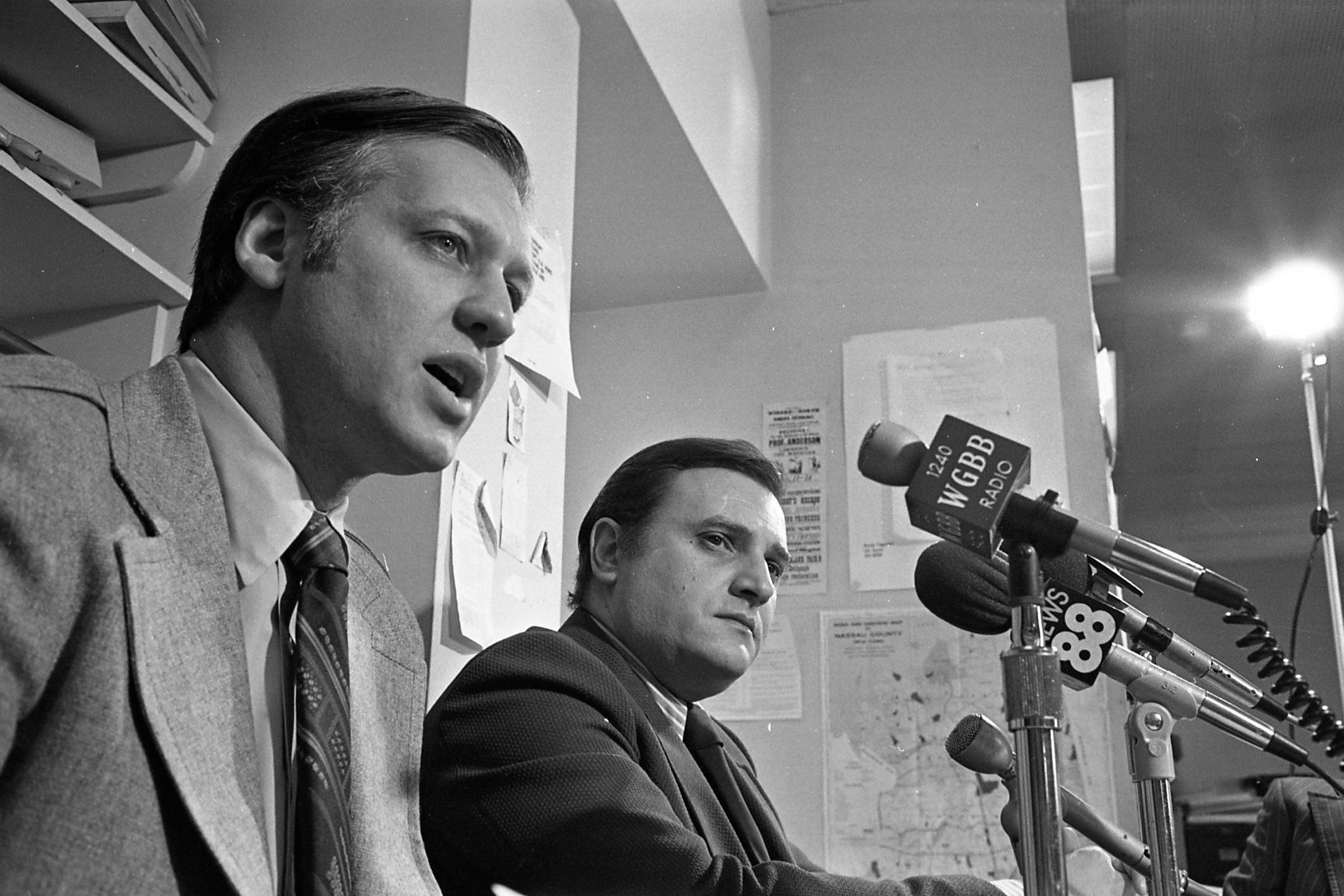

Assembs. Alan Hevesi, left, and Louis Yevoli at a news conference on Dec. 9, 1976, in Mineola. Yevoli helped convene an Assembly public hearing on contamination. Photo credit: Newsday / George Rubei

Privately, other officials were expressing alarm, too — although the public would hardly know it.

On Dec. 2, 1976, with the crisis at Grumman now in full view, company consultants huddled behind closed doors with state, county and federal representatives. According to notes produced by Geraghty & Miller, a dispute broke out between the EPA and the state. The EPA warned, according to the handwritten notes, “Don’t drink the water,” prompting a state official to disagree, and the EPA to repeat its concern: “no basis for levels that are acceptable.”

The same day, the now-deceased county health commissioner, John Dowling, who was listed as being present for the meeting, stated publicly: “If I lived in the area, I would continue to drink the water. We don’t have any information that the chemicals are harmful in drinking water.”

Clout at apex

That Grumman had a seat at the table among regulators showed its stature as Long Island’s economic powerhouse and a sophisticated political player.

Before political action committees were commonplace, Grumman had one of the nation’s largest. Its corporate PAC gave heavily — nearly $300,000 in the 1980 federal elections alone — to all kinds of candidates, including members of congressional committees overseeing defense spending.

Locally, its influence was omnipresent. “We know that local candidates are going to support Grumman. It’s ridiculous to think they’re going to vote against things that Grumman stands for,” the PAC chairman, Robert E. Watkins, told The New York Times.

George Hochbrueckner, a former congressman from Suffolk County who worked at Grumman facilities in the 1960s and early ’70s, said he understood why officials were deferential.

“They had the clout because they had the employees,” said Hochbrueckner, nicknamed “the Grumman congressman.” “Politically, they were hard to beat up on.”

That sway was hardly equaled by Hooker, even before its toxic dumping caused the 1978 evacuation of Love Canal near Niagara Falls.

There was no doubt Hooker was responsible for the vinyl chloride found at Grumman. But that opened the way for the blame officials placed on the company for the entire contamination crisis, TCE included, though Hooker used the chemical minimally compared to Grumman.

The Hooker Chemical Co. in Hicksville, shown in December 1976, was cited by regulators as the primary source of the contamination at the time. Photo credit: Newsday / John H. Cornell, Jr.

For a decade, the weaknesses of the case were overlooked. Although the lower levels of vinyl chloride in Grumman’s wells had to have come from Hooker — Grumman didn’t use the chemical — in at least one key instance the TCE could not have. Not only did the company dwarf Hooker in sheer size and sheer volume of TCE use, but, as Grumman’s own consultants noted in 1978, at least one of its tainted wells was north of the Hooker plant, away from the flow of area groundwater.

No Hooker representatives were listed as having attended the Dec. 2 meeting between government and Grumman officials. In the Geraghty & Miller notes, Francis Padar, Nassau’s director of environmental health, is quoted as saying, “may be only Hooker as source.”

For more than a decade after, regulators offered up Hooker as the poster child for Bethpage contamination, with Grumman doing nothing evident in news reports or available documents to dispute that.

Regulators, however, sometimes suggested that Grumman wasn’t completely blameless. Padar once did so himself. He issued a little-noticed public statement in December 1976 that named the polluting solvents found at Grumman and offering that the company may have had partial responsibility in putting them into the water.

But a Newsday article that same month captured the message that got through most clearly: “Most public officials speculate that the Hooker Chemical plant in Hicksville, which adjoins Grumman, is the source of the pollution.”

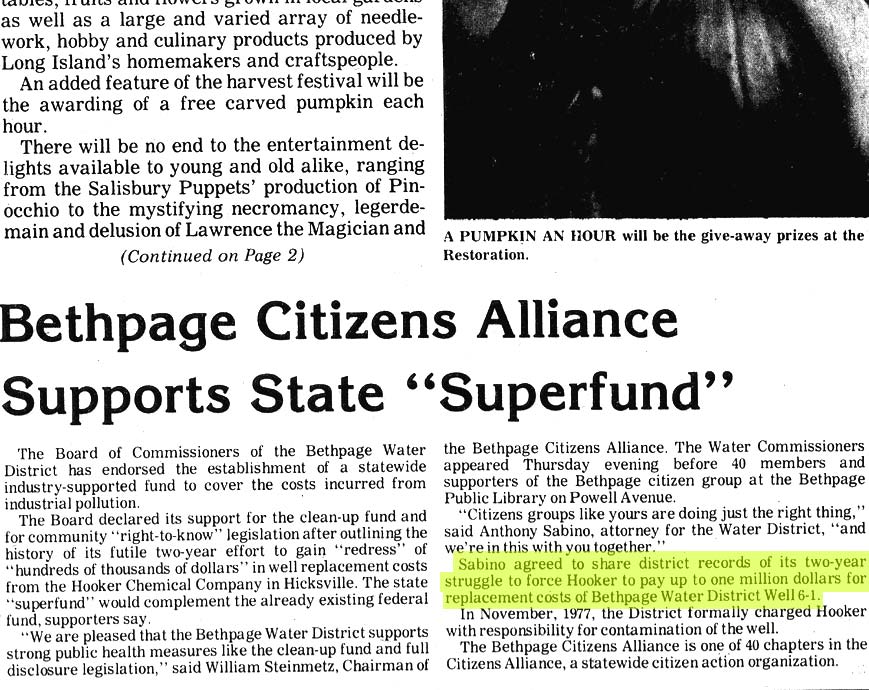

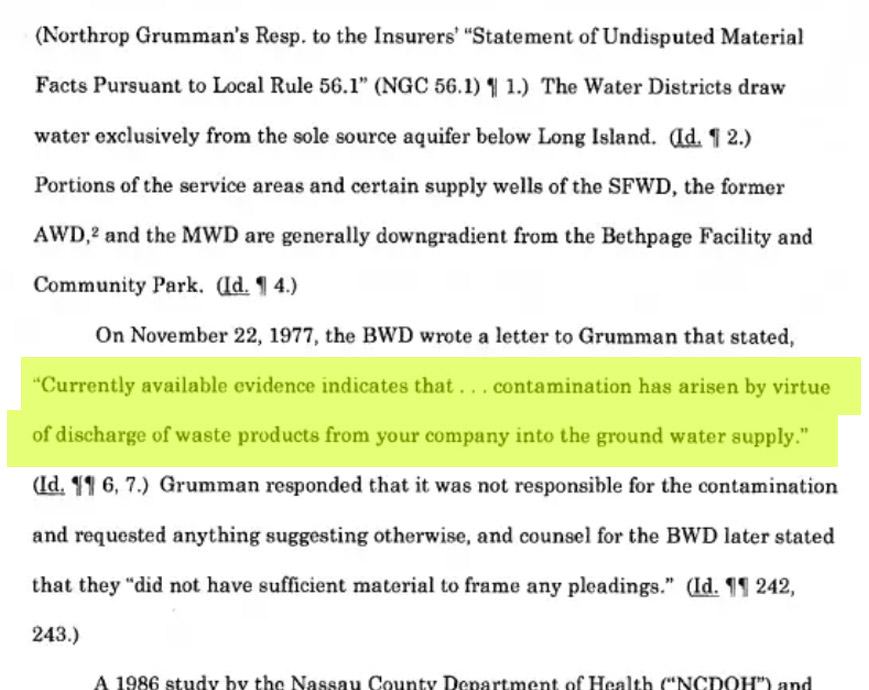

On Dec. 3, 1976, the Bethpage Water District shut its first public supply well due to TCE contamination. In a 1977 letter, cited in the insurance cases but never publicized, it formally blamed Grumman, writing, “currently available evidence indicates that … contamination has arisen by virtue of discharge of waste products from your company into the ground water supply.”

“It was very simple: We knew Grumman was responsible,” Greco, a district commissioner until 2003, said recently.

Northrop Grumman said in a filing with one of the insurance cases that the water district simply “dropped the subject.”

And when the district counsel, Anthony Sabino, spoke to the Bethpage Tribune in 1981, he blamed only Hooker. For the first time, the paper reported, he was sharing “district records of its two-year struggle to force Hooker to pay up to one million dollars for replacement costs” of the contaminated well.

“Sabino agreed to share district records of its two-year struggle to force Hooker to pay up to one million dollars for replacement costs of Bethpage Water District Well 6-1.”

Bethpage Tribune, October 1981 See full article

“Currently available evidence indicates that … contamination has arisen by virtue of discharge of waste products from your company [Grumman] into the ground water supply.”

A 1977 Bethpage Water District letter to Grumman, summarized in a 2014 federal court decision See full documentSabino recalled that the district at the time was taking its cues from the state, which decided to go after Hooker, rather than Grumman. Hooker, he explained, had already moved its operations from the area and therefore was an easier target.

“So the state tried to put the arm on Hooker,” Sabino said, noting that the Bethpage Water District “assisted because we did not care where remediation funds came from.”

“Don’t let anyone tell you Hooker was a major contributor to current issues.”

‘Anomalous spike’

In 1979, the state sued Hooker for dumping the vinyl chloride — and TCE — that polluted Grumman’s wells. Then-DEC regional director Donald Middleton declared to Newsday: “If it was in Grumman wells, it was theirs [Hooker’s].”

He credited Grumman with stopping the spread of contaminants by continually extracting tainted water from its property and using it for industrial purposes.

“We’re just lucky that Grumman is pumping enough water out of the ground to supply a small city, or the chemicals might be spreading through the Island’s water supply,” said Middleton, who did not respond to requests for comment.

Donald Middleton was the regional director of the State Department of Environmental Conservation in the late 1970s. He’s shown here at an event in West Sayville in February 1977. Photo credit: Newsday / Mitch Turner

While public officials stood by Grumman, it took up its own cause by carefully cherry-picking information it held privately.

In a 1982 public presentation, titled “Grumman and Long Island’s Groundwater: Protecting Future Resources,” the company included examples from a 1978 Geraghty & Miller report on plant industrial wastewater sampling.

The featured page showed that, at midnight, 4 a.m. and 8 a.m., Grumman was discharging an average of no more than four pounds per day of TCE back into the groundwater.

The presentation noted Geraghty & Miller’s conclusion that, “independent of the time of day,” the industrial wastewaters Grumman was putting back into the ground were cleaner than what they pumped out.

The company, however, omitted the prior page of sampling results, which Newsday culled from the full 1978 report left unsealed in the first Travelers Insurance case.

Two days earlier at 4 p.m., during peak plant production, Grumman discharged an average of 17.17 pounds per day of TCE back into the groundwater. That would equal more than a gallon of pure TCE, enough to contaminate 292 million gallons of groundwater, according to a filing by one of the company’s former insurers.

The filing called the omission “a further attempt to deflect blame for the widespread groundwater contamination.” Northrop Grumman said in the insurance case that the reading was an “anomalous spike.”

The full 1978 report contained another detail left out of the public presentation: The consultants attributed the levels of chemicals found to Grumman’s own “housekeeping practices (spills, cleanup of equipment, etc.)”

In the late ’70s, the state could have believed, as Middleton proclaimed, that Grumman’s extensive pumping of industrial wastewater was saving the day, containing the pollution in the shallowest parts of the aquifer. But 30 years later, the company acknowledged that its pumping had the opposite effect.

In a 2009 presentation, Northrop Grumman wrote that it had actually “distributed [contamination] laterally and vertically throughout the region.”

Humann, the Bethpage Water District consultant, said the volume and depth of Grumman’s pumping likely accelerated the pollution’s spread by repeatedly extracting and returning it to the aquifer.

A slow reckoning

As national and state awareness of environmental hazards grew, Grumman’s governmental relationships became less effective.

In 1979, the state established a list of hazardous waste disposal sites, the beginning of its Superfund program to identify and clean industrial contamination. Grumman eventually made the list — one of the company’s drying beds for wastewater sludge alone handled 1,300 tons per year, the state reported in 1980.

Formal notice came in December 1983, when the state warned the company in a letter that it was a “potentially responsible party” for cleaning up pollution at its Bethpage facility and “may be responsible for the release or threatened release of hazardous substances.”

Because the state said it had insufficient data on Grumman’s practices, the effects were minimal — almost no action was required.

But the discoveries kept escalating.

In 1986, the Navy acknowledged that “large volumes of hazardous wastes were stored” on the 100-acre piece of the Grumman site that it owned but that the company operated — and that they were kept, until 1978, “without comprehensive containment safeguards.”

That same year, Nassau public works officials were investigating a countywide water shortage and drilled a series of wells. Near Grumman, they found something other than a “water quantity problem.”

They discovered the plume.

“While public relations was making it a quantity problem, we did a model that proved it wasn’t,” John Caruso, who worked for the county at the time, said in an interview.

The county asked for help from the U.S. Geological Survey. Together, they developed the first formal mapping of the contaminants spreading from Grumman’s site and found them moving in much the way the company’s consultants had predicted a decade before.

John Caruso, a Town of Oyster Bay public works deputy, speaks about groundwater contamination in June 2012, when he was a Massapequa Water District commissioner. Photo credit: Daniel Goodrich

“A groundwater plume was found to be sinking and moving south southeast,” the report warned.

“If we would have started [the cleanup] back then,” said Caruso, a former Massapequa Water District commissioner who now serves as an Oyster Bay town public works deputy, “it wouldn’t be what it is now.”

In December 1986, state officials met privately with Grumman and requested that the company investigate whether it had contaminated area water. An internal Grumman memo summarizing the meeting stated that the request “could be the first step leading to a very serious and expensive liability, if it were determined Grumman contributed contaminants to the groundwater and a cleanup of some kind was required.”

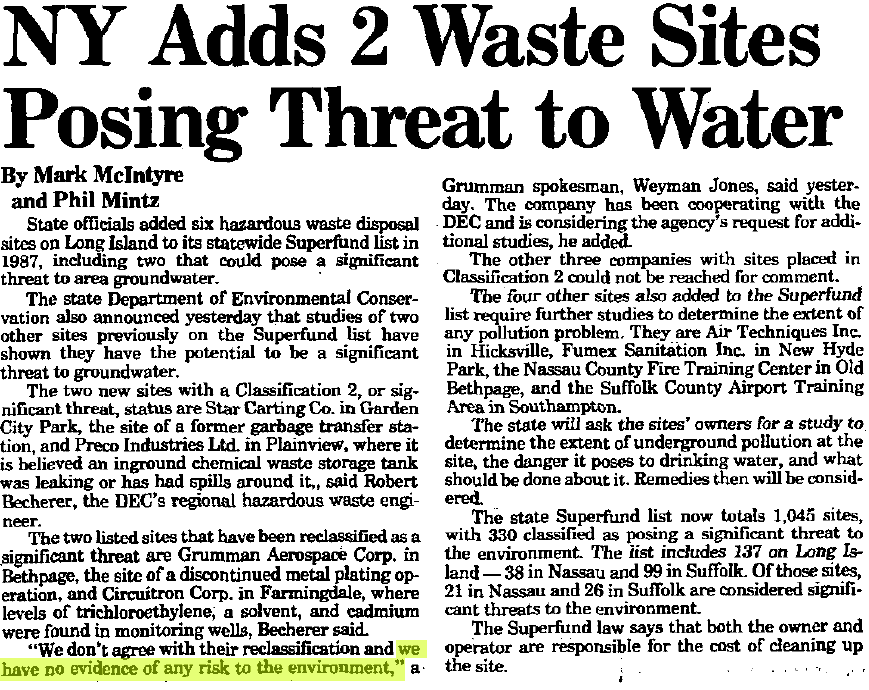

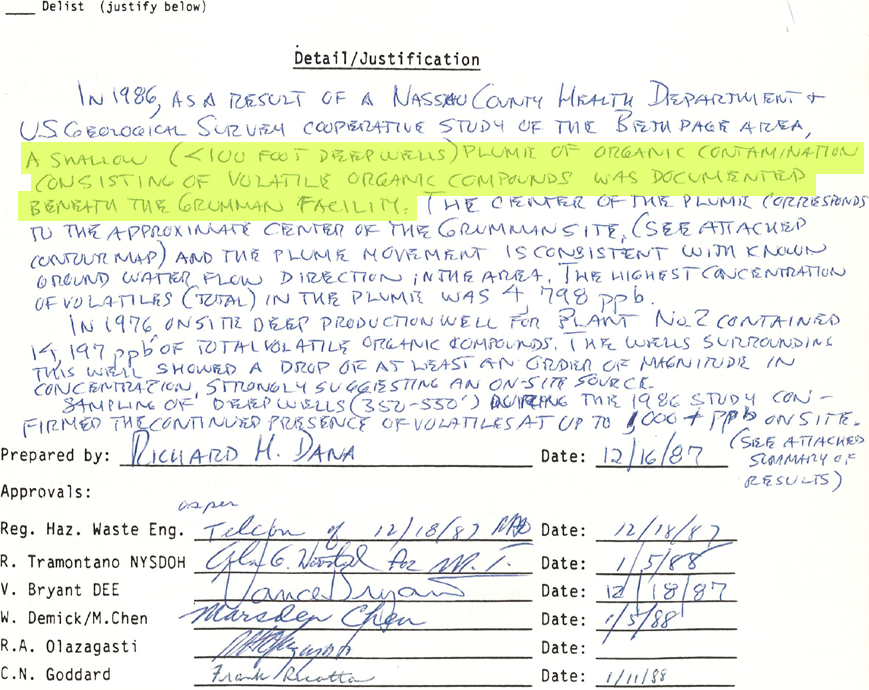

Exactly a year later, the state changed its Superfund designation of the company’s Bethpage facility, elevating the risk level: “The reason for the change is as follows: hazardous waste disposal confirmed, groundwater standards have been contravened.”

This forced action from Grumman for the first time. The state reported discovery of TCE levels within the plume on the company’s site at as high as 810 parts per billion, attaching a hand-drawn map that provides the contamination’s earliest known visual representation, with data “strongly suggesting an onsite source.” Those levels would later rise, in some of the untreated, raw groundwater, to the tens of thousands.

Then-company spokesman Weyman Jones responded in Newsday in March 1988: “We don’t agree with their reclassification and we have no evidence of any risk to the environment.”

“…we have no evidence of any risk to the environment.”

– Weyman Jones, then-Grumman spokesman

Newsday, March 3, 1988 See full article

“A shallow … plume of organic contamination consisting of volatile organic compounds was documented beneath the Grumman facility.”

1987 state department of environmental conservation report See full documentThat year the Bethpage Water District privately told company officials that the second of its public supply wells was contaminated with TCE.

A private reckoning approached.

The company launched its first contamination study of the site that would be overseen by outside regulators. Later in 1988, it confirmed that rather than the vinyl chloride produced by Hooker, TCE and a similar compound, tetrachloroethene, also known as PCE, were the most prevalent contaminants in nearby groundwater.

All silent

Grumman, however, again remained quiet as it took its first remedial steps.

In March 1989, internally acknowledging the situation’s gravity, it opened its first on-site installation to remove contaminants.

By August, the company was deep into private negotiations with the water district. The district wanted money to erect its first similar device, called an air stripper, for TCE-contaminated wells.

That was the backdrop for an Aug. 16, 1989, meeting between a Grumman executive, engineer, attorney and insurance manager and Travelers, the company’s insurers. It was summarized in a particularly consequential Travelers memo, labeled “PRIVILEGED & CONFIDENTIAL” and left unsealed.

The summary began by outlining a brief history of Grumman’s TCE use in an unprecedented way: “Groundwater at south end of [Grumman] complex has contained TCE for a long time. TCE has been used there since 1949,” it reads, building up to: “Data is conclusive that it is Grumman plume which is contaminating the [Bethpage] Water Districts [sic] well.”

After noting that the district wanted $1.3 million from Grumman, the memo emphasized: “No question regarding liability as there are no other direct parties [that] appear to have contributed to contamination yet.”

It was a remarkable conclusion after Grumman’s years of challenging the extent of — and its responsibility for — the pollution.

But it was a private one, still out of the eyes of a public that had watched the company contest efforts to lay the problem at its door.

Instead of debating the facts, we are dealing with the issue.

Jack Carroll, Grumman official, to the Bethpage Tribune in 1990

Instead of a public admission, in May 1990 one of the Grumman officials present for the insurance meeting joined a group interview with the weekly Bethpage Tribune that directly contradicted the memo’s conclusion.

The paper summed up the interview this way: “Grumman doesn’t admit liability on the issue of contaminating Bethpage wells, however Grumman acknowledges that wells on their Bethpage site exceed Nassau County Board of Health standards.”

According to the article, Cassell, Grumman’s vice president of product integrity and environmental protection, further suggested that the contamination either entered the ground in the 1940s through Grumman’s operations or that the company’s pumping may have inadvertently drawn it in from neighboring manufacturing plants.

Another company official, Jack Carroll, added, “Instead of debating the facts, we are dealing with the issue.”

The headline accompanying the story was “BETHPAGE WATER AMONG THE SAFEST; Rumors of Grumman Contamination Pose No Threat.”

This was a last refrain from Grumman’s era of open denial.

Over the next quarter century, it was replaced by a far larger commitment to extracting pollutants from its original property but also by fighting some of the most aggressive measures to address the plume as it spread.

And in that effort, Grumman was often joined by regulators.