The Long Islanders who helped take America to the moon

In the late 1950s, America’s chief arch-nemesis was the Soviet Union. Americans wanted to beat the Soviets at everything, including space exploration. Both countries were building systems to send into space and be brought back to Earth. Then, in October 1957, the Soviets launched Sputnik, a satellite that successfully orbited Earth.

The Soviets had one-upped America.

“NASA announced Grumman has won the lunar module. And of course Bethpage went berserk.”— Sam Koeppel

Four years later, in 1961, President John F. Kennedy raised the stakes in America’s space race with the Soviets. Appearing on national television, Kennedy declared that Americans would put a man on the moon before the 1960s ended. His proclamation lit a fuse under everyone interested in space exploration, including the executives at Grumman, an aerospace and defense technology company.

The company officially joined the race by submitting a bid proposal to build a moon spacecraft. Grumman was one of many companies competing for the NASA contract.

Sam Koeppel, 87, of Floral Park, was the technical editor who massaged every word of the company’s bid proposal. He still remembers how particular NASA was about how the proposal should be submitted.

“They didn’t want all the heavy detail of a lot of books,” said Koeppel, who has been a museum docent for 15 years and worked at Grumman for 23 years. “They wanted 50 pages answering 20 questions specifically on certain things that NASA wanted to know about. Labor Day 1962, we delivered the proposal after a strenuous six weeks.”

In November 1962, the good news came.

Koeppel and other Grummanites said they believe the company won because they pitched a unique method for getting astronauts to the moon called lunar orbit rendezvous.

The celebrations were short-lived, as the real work was about to begin. The president had issued a challenge, time was running out and no one at Grumman had ever built a spacecraft.

Kennedy made his declaration “in May 1961 and we all counted and it was only 8 1⁄2 years and we hadn’t really even gotten a sketch yet,” Koeppel said.

“It actually got to a point where we were working so many hours that people were leaving their [work] areas filthy because we didn’t have an opportunity to do the cleaning.”— Mike Lisa

Grummanites desperately wanted to meet Kennedy’s deadline, so they worked long hours week after week.

Mike Lisa, 75, of Hicksville was an environmental test engineer on the team. One of his most vivid memories was the 50-hour workweeks. Working on the spacecraft was fun and everyone enjoyed the overtime pay, Lisa said, but the long days eventually caught NASA’s attention.

“It got to a point where NASA came down,” said Lisa, who worked for Grumman for 36 years until retiring in 2009. “I’ll never forget this — NASA came down and said ‘Hey, we know you guys have a goal, but you’ve got to get this place straightened out.’ ”

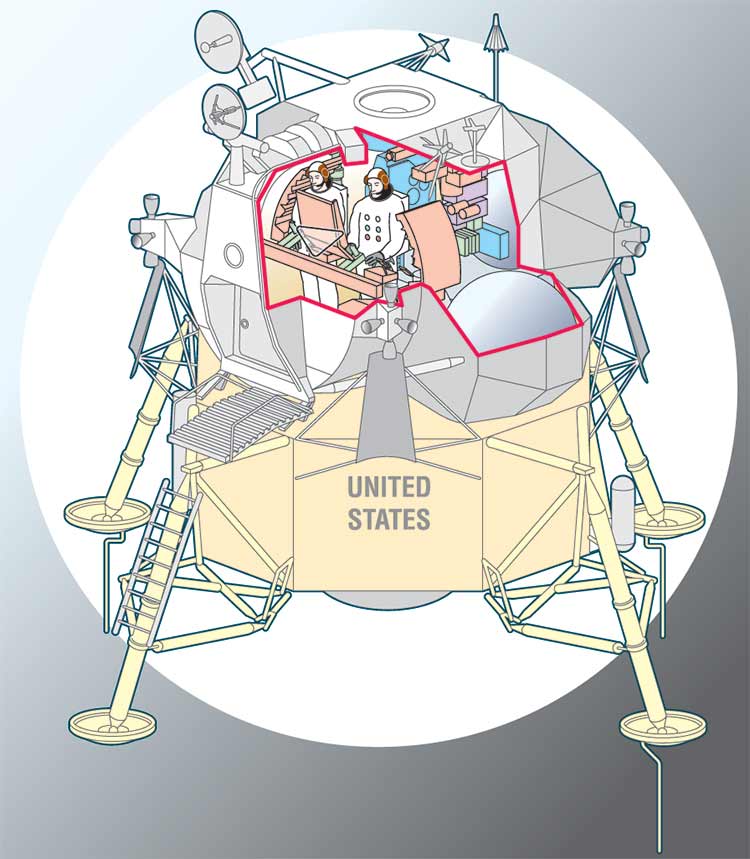

Most of the spacecraft design work centered on using lightweight materials. That’s because a heavier spacecraft would require more fuel and NASA was hoping to save money on fuel costs, the Grummanites said.

With every addition or modification to the spacecraft, Ernest Finamore, 91, who worked for Grumman for 45 years and then became a museum volunteer in 1999, was in charge of inspecting it. He checked the tubes used for the hydraulic system. He checked all the electrical wires and the connectors attached to them. And when he was finished, he had to call a Navy engineer who would double-check his work.

This back-and-forth went on for months. Finamore and his team did quality assurance while Gran worked on a team that calculated how much fuel was needed for the spacecraft to complete different maneuvers.

Finally, the work was finished and out came the spacecraft — all 8,650 pounds of it. The Grummanites had beaten Kennedy’s deadline with time to spare.

Newsday / Rod Eyer

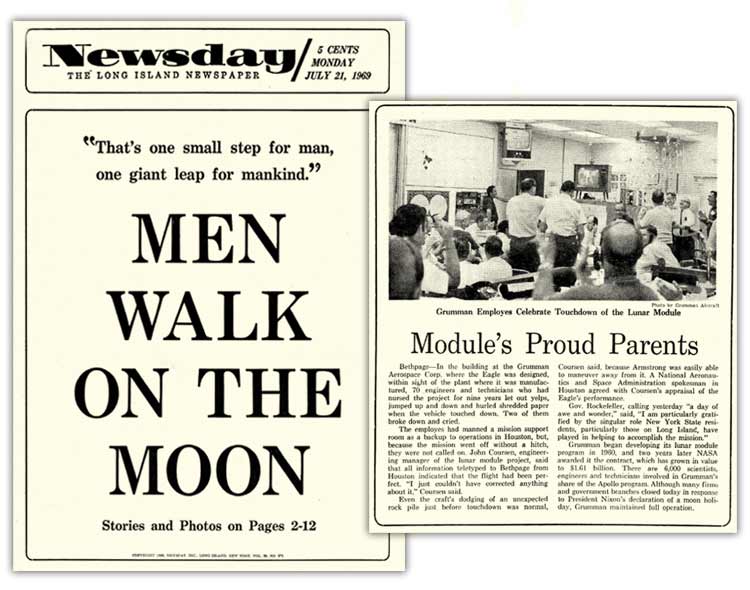

The module was shipped to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where it was launched into space. It landed on the moon on July 20, 1969. The event aired on national television and captivated the world’s attention.

As it touched down, Grummanites watched with excitement and a hint of nervousness.

Armstrong and Aldrin’s famous trip marked the end of a job well done for the Bethpage Grummanites. In 1969, Newsday reported that two Grumman employees broke down and cried during the moon landing.

“We were not only amazed at what was going on, we were worried that something [ wrong ] would happen.”— Alan Contessa

No matter what role you had or how little you were involved, everyone from the lunar module team watched the men land with the same thoughts racing through their minds, said Contessa, 70, of St. James, who was a Grumman thermal insulation technician and worked for the company for three years.

“There was a little nervousness going on,” he said. “We were sweating it out. Nobody wanted to be the guy who made the mistake that screwed this up.”

How I became a Grummanite

Mike Lisa, assistant manager of volunteer services for the Cradle of Aviation Museum

After graduating college I had worked for Hazeltine Corporation. That’s located in Greenlawn. I was doing IFF engineering, which is Identification Friend or Foe. I did that for about two years, then I started to hear about Grumman.

It was really strange because Grumman was only one block from my house and I never, ever thought I’d be working for this place. Their planes used to fly over the house and I said, “You know, it’s about time.” So I went ahead and put in an application into Grumman and I was hired.

I was hired as an instrumentation environmental engineer, which was extremely interesting. It gave me the opportunity to crawl all over these spacecrafts and test probably 75 percent of the structures that make up the craft. And when I’m saying test, we used to go into a thing called the stress-to-overstress. The idea was to put them on shakers — these were electromechanical devices — and we’d actually shake the daylights out of them until they cracked or broke. And the idea was to find out exactly how much these things can take. Will they take the trip to the moon? What happens if we have a rough landing? But after a while, working with the instrumentation test group, I was asked to take over the environmental engineering test group.

That’s where we did quite a bit of testing as far as high-vacuum testing, vibration testing, salt spray testing, acceleration, deceleration, all those crazy things. I worked on the LEM throughout its entire life span, which was, for me, from 1963 to around 1972.

After that, my stint with the space program, I then went into corporate and I got involved in real estate, acquisitions, breaking down departments, reducing the work staff. I did that until 36 years passed.

Alan Contessa, Lunar Module Restoration Volunteer at the Cradle of Aviation Museum

In 1966, I was 19 years old, single and in good health. That’s what you call draft bait — ’cause we had a draft back then. Vietnam was going hot and heavy and I knew I was going to be drafted by the Army, so I joined the Air Force. I figured it was the safe way to go. As luck would have it, I got a medical discharge after being in the Air Force for less than a month.

Now I was home, my military obligation was complete and I needed a job. So I walked into Plant 28, which is on South Oyster Bay Road, and just walked in off the street and applied for a job at Grumman. And I was hired.

I was hired to make ground support cables, which meant crimping pins on the ends of these cables that they hook up. You can imagine the cables you need for electrical supply to spacecraft or a rocket. It was a very boring thing to sit there crimping pins and doing that sort of thing. So I actually quit.

I gave two weeks’ notice. I was going to move on somewhere. But on the last day, I changed my mind and said, “Is it all right if I stay?” They said, “Fine. You can stay.” About a week later, they transferred me out of that department. I guess they wanted to get rid of me, and into the upholstery department where they were making the thermal insulation for the lunar module.

So it was kind of a crazy way to get there. That was a total new world, to see people in smocks, hats, gloves, crinkling up insulation in a clean room. The lead man who was there, who was a dear friend of mine for years after this program, he could see the look in our eyes from me and a friend who came there. He said, “Guys, give it a chance. It’s not a bad job.”

So, we said, “OK. We’ll stay.” And the rest is history.

I wound up going to Plant 5 working on the LEM. I went to Houston for a year. I was in Cape Kennedy before the Apollo 11 launch to do an emergency update of the insulation, which had to be done on the launchpad on top of the Saturn 5 rocket.

For a guy who kind of fell into this, it was pretty good. That’s how I got into this.

Sam Koeppel of Floral Park

I graduated from Brooklyn Polytechnic in 1951 as an aeronautical engineer. At the same time, I had become interested in writing for the newspaper and so, by that time, I had also become the editor of the college newspaper — The Reporter. That was the name of the paper, which won an All-American award that year.

I took a job with the United States Navy in Pennsylvania working on, believe it or not, F-6F Hellcats, which is a Grumman airplane, modifying them for drone targets after World War II. All of those airplanes were turned into pilotless drones to be shot down by Marine pilots in training. They were the first drones I ever saw.

I stayed there a little over a year and then was hired by Republic Aviation in Farmingdale, except that the office that I was hired to was in the Dun & Bradstreet Building in New York City where the F105 was being designed on the top two floors — not far from where the old World Trade Center was.

I became a wing designer and after 13 months there, the Army didn’t give me any more deferments. They grabbed me and put me in the infantry in Fort Dix, and I wound up two years in the Army. Most of that was spent at Picatinny Arsenal in New Jersey, which now does not exist anymore. That was an ammunition test and design center.

On discharge, I went to Sperry Gyroscope Company here on Long Island as a technical writer and wrote the operating manuals for autopilot systems that were being built by Sperry Gyroscope Company. From there, after Sperry lost many contracts, a neighbor of mine told me to come in and say hello to Grumman, which I did and I was hired in the presentations department as an editor in August of 1960.

Since I had a degree and was one of the few editors that did have a degree, I was assigned as an engineering writer to assist the preliminary design group headed by, at that time, Tom Kelly. From there on, I spent the next two years working with all the preliminary reports that led to the proposal for the LEM.

Richard J. Gran

When I graduated from college in 1961, I had a degree in electrical engineering — bachelor’s, of course. I wanted to go on and study some more, but I also didn’t know exactly what kind of engineering I wanted to do, so I ended up working for a year at Brookhaven National Laboratory.

I lived in Farmingdale, and that was a one-hour commute one way. It was really wearing me down. But I got a chance to design a control system. And what a control system is — you know what you want to do and you have to figure out a way of forcing it to happen. That’s a control system. And I liked it. It was really fun. I had never done an honest-to-goodness control system. You build it and you see it work and say, “Wow, that was really neat.”

I realized that I was not probably going to see another control system design at Brookhaven again because it was not what they specialized in, obviously. So I left Brookhaven and I came to work at Grumman. I lived in Farmingdale; not even a five-minute drive to get to Grumman instead of an hour one way. I started designing little servomechanisms for the A-6 airplane. Did that for about nine, 10 months, then decided I wanted to do something more advanced.

I had heard about a group called Dynamic Analysis. They did all of the engineering design, which required sophisticated mathematics basically — structural vibration, dynamic guidance for guiding a vehicle, navigation and control.

So I went over and I interviewed with a fella named Ralph Whitman and he liked me and immediately assigned me to the LEM because they had just lost a person working on the LEM. So, literally, overnight, I went from being a servomechanism designer to an employee of the LEM. Initially, I was calculating the amount of fuel the jets would use when they made a turn to do what was called an alignment maneuver.

Ernest Finamore

My father, Antonio, worked in Plant No. 1 for about a year in 1942, forming sheet metal parts on a hydraulic press.

Just before Christmas of that year, Pop injured his arm while working the big press. Now he had no job and no income, with a wife and six children at home. Mom had a part-time job making dresses on a Singer sewing machine.

At that time, I was the oldest and, at 16, I delivered newspapers and the Saturday Evening Post magazine. I was also a Sunday afternoon golf caddie at Bethpage golf course. On Thursday evenings, I worked at John Pizzuti’s restaurant by the Plant No. 1 gate. We served spaghetti dinners to the Grumman night crew. I made 28 cents an hour.

About two weeks later, Mr. Tom Rozzi, the new Grumman security chief and a neighborhood friend, came to the house to check up on Dad and his financial situation. Tom and my parents agreed to take me out of high school and Tom would hire me to work at Grumman.

On Feb. 22, 1943, I turned 17 years old and they let me leave school with a nice letter of recommendation as to my mechanical ability and integrity.

On March 8, 1943, I entered Plant 2 and learned how to buck rivets on the tail section of the TBF Avenger. They paid me 69 cents an hour. I worked until December. On January 4, 1944, I joined the U.S. Navy with five other friends, because we didn’t want to be drafted into the Army.

I returned to Grumman in July of ’46 and worked until the January 1947 postwar layoff. I was rehired in March 1948 and worked through all phases of major installations of engines, propellers, fuel tanks and flight controls. Because I had earned my private airplane pilot’s license (via the Grumvet Flyers Club at Plant 4), Grumman promoted me to plane captain on production test flights in April 1948.

For 3 1⁄2 years, I flew as mechanic and co-pilot in the Albatross amphibian and the S2F submarine hunter with the Grumman test pilots. In 1956, they promoted me to the inspection department. I inspected detail parts, minor and major assemblies and final engineering and test on the A-6E, EA-6B, F-14, E-2C Hawkeye, and I spent six years on lunar modules numbers 5 to 13.

For the past 14 years, as a museum docent, I show and tell about the lunar modules and moon landings at the Cradle of Aviation Museum on Wednesdays.

We still have six Grumman retirees who do aircraft restoration and build exhibits for the Cradle, on Tuesdays.