Battling the coronavirus inside one Long Island hospital.

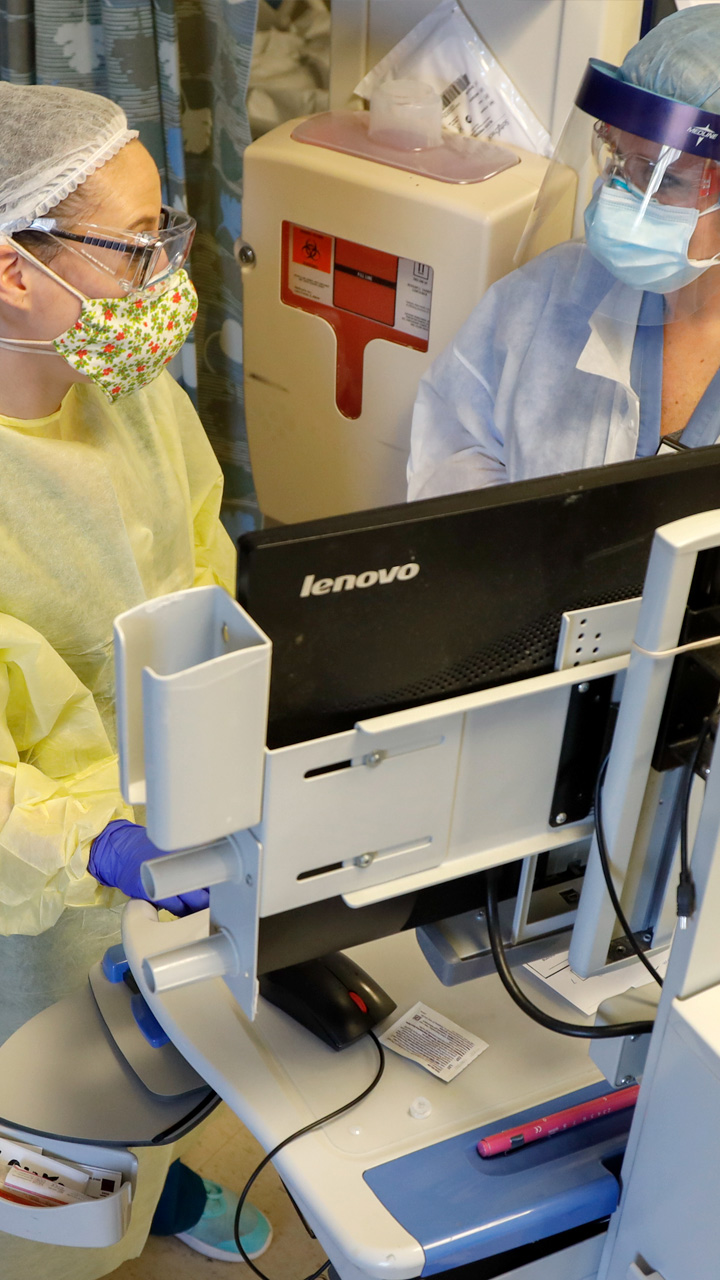

They are clad in protective gowns, gloves, face masks and shields. Beneath their coverings and professionalism, their emotions in life-and-death situations are impossible to read.

And despite their unending best efforts, death is a constant presence, never more intimately than for nurses called on to wrap bodies every day.

In the darkest moments, hope comes in the form of a Beatles song over the loudspeaker — “Here Comes the Sun” means their tireless work has allowed another patient to go home.

At the heart of the coronavirus pandemic, the staff of Mount Sinai South Nassau Hospital in Oceanside share their struggles, fears and hopes with embedded Newsday journalists.

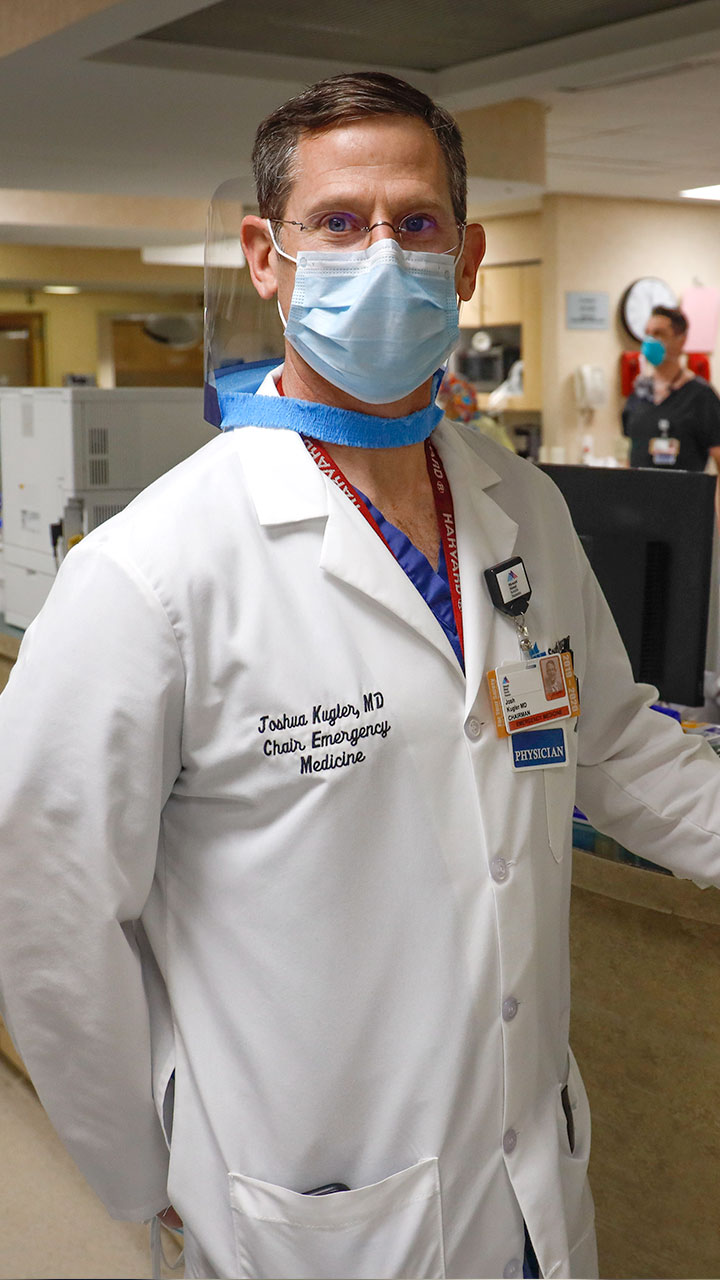

The rapid response call goes out when an ambulance pulls up with a patient who has “coded” on the way to the hospital. His life hangs in the balance while a team coalesces to intubate the man and start oxygen flowing to his lungs. Dr. Kugler observes and explains.

Amid an influx of infectious patients, Chief of the Emergency Department Dr. Joshua Kugler says, “there is no non-COVID area” in the ER or almost the entire 455-bed hospital. He and his staff move efficiently as ambulances deliver desperately ill people to a treatment area well over capacity.

WATCH NOWSeven months pregnant, chief physician assistant Courtney Ciesla plans to care for patients until she goes into labor in the same hospital.

WATCH NOWMany on the medical staff say they most fear bringing the virus home and infecting loved ones. Dr. Eugene Perepada, 37, likely infected both his wife and his 6-week-old baby, sending the infant to the hospital for two days. Both have since recovered.

With a steady progression of coronavirus symptoms, Dr. Perepada says he was afraid of dying. But, homebound while recovering, he felt guilty for leaving his friends and colleagues to work without him.

He grew up on a farm in Melville and served in the military — now Dr. Kugler is the chief of the emergency department. He recalls how his department saw six deaths on a single day, April 7.

The “velocity,” the acceleration of coronavirus-positive patients arriving at the hospital, was unprecedented. He hopes the curve is flattening.

There is no downtime for emergency staff. Even pictures fall short in conveying their fight against the pandemic, or the battles waged across the hospital.

The number of patients alone — some in medically induced comas, some crying out for air — overwhelms the senses. The beeping of monitors, swirling motion and chatter make it difficult for an outsider to focus in any one direction. But compassion anchors humanity in the chaos.

Patients often die alone because visitors are barred from entering. Others have difficulty staying in touch with loved ones or cannot because they are unconscious. Doctors and nurses communicate with families through video chats, in dire cases to show the severity of their loved-one’s condition. Sometimes aggressive intervention would be futile.

WATCH NOWDuring long, stressful hours, the staff searches for moments of hope and morale-boosting reminders that their work is paying off in lives saved.

Suddenly, a clip of the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun” offers 20 seconds of hope as the hospital discharges a COVID-19 patient.

WATCH NOWWhile the Emergency Department’s patient load has declined, the Intensive Care Unit is still pushed to the brink. Here, almost every patient is on a ventilator, many in medically induced comas.

WATCH NOWElzbieta Zanio worked in the cardiac catheterization ward, where doctors inserted catheters to diagnose and treat heart conditions. “Your eyes are open your entire shift” she says, as she’s never cared for such intensively ill patients.

There were 18 patients in this ICU. All needed the support of ventilators to breathe and most were sedated into induced comas. One also needed a tracheostomy, where a tube is placed through the neck into the windpipe.

Dr. Scott Roethle, who lives in a Kansas City suburb, says he was inspired by his Christian faith to treat patients at the epicenter of the pandemic.

WATCH NOWHe says his wife wasn’t afraid that he was heading into a dangerous assignment. Her biggest concern: being left for two weeks to take care of their four children alone.

A patient is connected to life-sustaining devices providing blood pressure medication, antibiotics, sedation, feeding and assistance breathing.

The medical team’s movements appear well choreographed as they work together to move and treat infected patients.

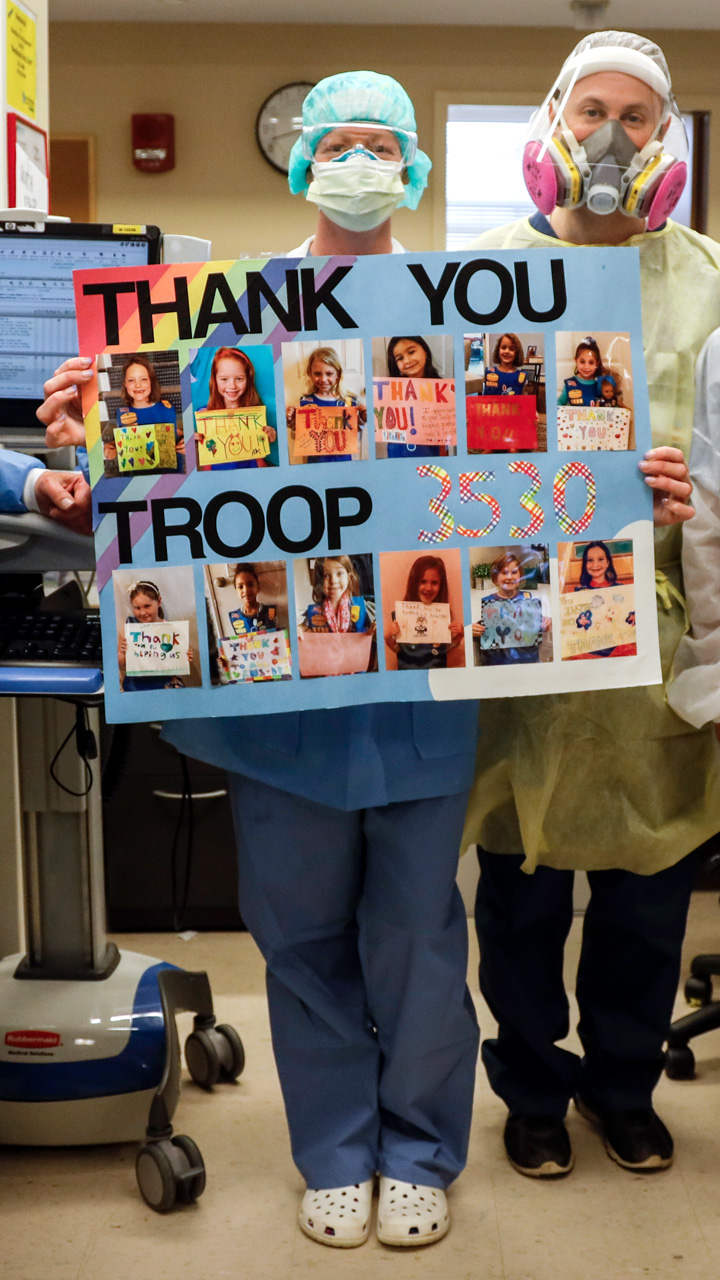

While observing the ICU, we’re reminded of the community support that Mount Sinai South Nassau employees talk about regularly. Restaurants deliver free meals and area residents donate personal protective equipment. Letters, cards and messages pour in.

Without proven therapies to stem COVID-19, patients’ success is not always in the hands of the hospital staff. The hospital morgue can hold up to 12 bodies. After it hit capacity, the hospital opened three external morgue containers in a parking lot.

Forty-four bodies awaited a medical examiner at the time we visited the hospital.

Nurse manager Nydia White and nurse educator Katie DeMelis tend to the body of a patient who succumbed to COVID-19.

They clean with a delicate touch, extract lines that had once sustained life and wrap the body in a double-layered white sheet and bag.

WATCH NOWAfter a death, nurses review a patient’s information, including religion. Some faiths have strictures about preparing corpses. Typically, nurses cross and tape a decedent’s arms and legs before wrapping the body in a white sheet. They refrain, for example, if the person was Orthodox Jewish. In Orthodox practice, after a body is covered in a sheet, volunteers from designated burial societies prepare the body by ritually cleansing and dressing.

The hospital had recorded 238 COVID-positive deaths as of April 17.

Debbie Rifenbury, 61, says she’s glad she quit smoking 39 years ago. She is one of only 28 COVID-positive patients to come off ventilators as of April 17.

WATCH NOWRifenbury, like others who recover from more severe cases of COVID-19, will have a long road to full recovery. The disease can ravage the lungs, causing lasting damage, but Rifenbury is determined. “I will survive and I will get better,” she says.

When she’s well enough to be discharged, the hospital staff will celebrate her exit with 20 seconds of “Here Comes the Sun.”

Visuals and text: Jeffrey Basinger Additional reporting: David Olson Project editors: Don Hudson, Arthur Browne Associate producers: Robert Cassidy, Seth Mates Digital design/UX: Matthew Cassella, Anthony Carrozzo and James Stewart Development: TC McCarthy Digital Quality Assurance: Pradeep Bhatee Additional project management: Heather Doyle Social media: Anahita Pardiwalla Copy editing: Bob Shields, Doug Dutton and Don Bruce Print design: Seth Mates