In proud Bethpage, years of worry take emotional toll

Grumman’s major role in the community’s history is noted still on this "Welcome to Bethpage" sign on Powell Avenue. Photo credit: Newsday / Steve Pfost

Theirs is a community that once helped put men on the moon. Now Bethpage residents don’t trust the water coming from their taps.

They wonder whether the tomatoes they grow are safe to eat.

For nearly two decades, their kids have not been able to use a baseball field on land donated by the Grumman Aerospace company, which utilized part of it as a toxic waste dump.

Real estate agents say some prospective buyers shy from this community of trim homes and honored schools because of the pollution’s stigma.

Hovering behind all that, in conversations around dining room tables and in community meetings, are fears about whether the contamination has caused cancer.

There’s no proof it has, but residents’ wariness has caused them to question the validity of a state investigation that failed to establish a link.

Concern. Skepticism. Frustration. Beyond its other effects, the toxic legacy of Grumman’s operation has taken an emotional toll on Bethpage and sown deep distrust of the company, the U.S. Navy, which owned part of its site, and government officials.

Northrop Grumman contractors drill to install a monitoring well at William Street and Broadway in Bethpage in February 2015. Photo credit: Barry Sloan

Amid an incomplete cleanup of a toxic mess that state officials and Grumman minimized and even denied for decades, what was long called the “Bethpage plume” has grown to be 4.3 miles long, 2.1 miles wide and as much as 900 feet deep.

Many residents are galled by the name itself, feeling it connotes that the community is responsible for its own misfortune and obscures the pollution’s spread. Treatment is required not only at drinking water wells serving Bethpage, but also for Plainedge, South Farmingdale and North Massapequa, and parts of Levittown, Seaford, Wantagh and Massapequa Park.

“This has nothing to do with our community and its people who are the victims of this environmental disaster,” said Peter Schimmel, 51, a lifelong Bethpage resident.

The state, in official documents, now calls it “the Navy Grumman” plume.

The bitterness is particularly deep because of a sense of betrayal — the company was Bethpage’s paternal corporate anchor and Long Island’s largest employer. But its days hosting community picnics and making military fighters and the Apollo 11 lunar module are long gone.

In 1994, Grumman was acquired by rival defense contractor Northrop and became part of the Northrop Grumman Corp., now headquartered in Virginia. The former 600-acre Bethpage operation, which at its peak employed 20,000, has been reduced to nine acres and 500 workers.

“It’s hard for people to understand you could put a man on the moon, you know, you can do all these things in space, and we’re totally ineffective when it comes to cleaning up the contamination we make here on Earth,” said Sandra D’Arcangelo, 76, a 40-year Bethpage resident and member of a Navy community advisory board. “My community has totally lost confidence in the effective remediation of this site. We have no confidence Grumman or the Navy would do the right thing.”

Grumman planes were on display at the company’s annual picnic in this undated photo, which appeared in Newsday in March 1994. Photo credit: Newsday / Stan Wolfson

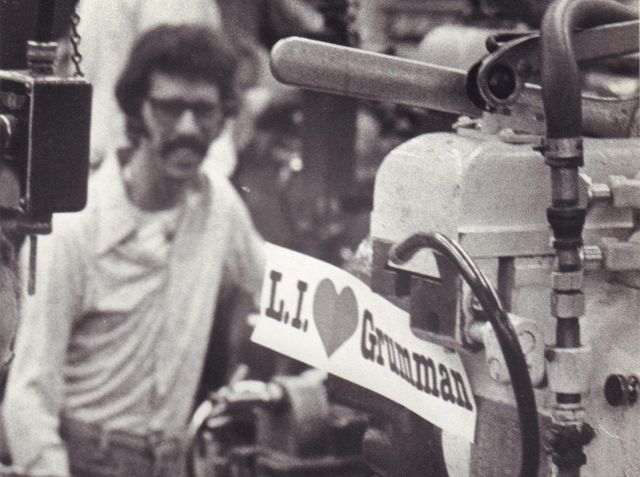

A banner proclaiming Long Island’s love for Grumman is posted on a machine in the milling area of the Bethpage facility in November 1981. Photo credit: Newsday / Daniel Goodrich

Employee cars fill a parking lot at Grumman Plant 5 in January 1975. The company employed more than 20,000 people during its heyday on Long Island. Photo Credit: Newsday / Jim Peppler

The most common pollution concern in Bethpage is about drinking water, primarily the prevalence of trichloroethylene, or TCE, a carcinogenic solvent that Grumman used to degrease metal parts. But contamination has also been found in soil at Bethpage Community Park. Vapor pollution has seeped into basements, leading the Navy to install treatment systems. And there was enough toxic soil in one neighborhood for the state to order the dirt removed from 30 homes’ yards.

The Bethpage School District has spent $250,000 drilling its own wells to test groundwater and install vapor barriers around schools. It’s found some elevated levels of radium in water around buildings and radon, the gas it breaks down into, in unoccupied school basements. The state for years maintained that the elevated levels are likely naturally occurring, but radium was also used in luminescent paint on aircraft dials and gauges.

Occasionally, heavy equipment will turn up in residential streets, drilling down thousands of feet for another sample of the plume.

Grumman and the Navy, which owned a sixth of Grumman’s site, have spent extensively on contaminant extraction and testing and have joined government officials in trying to reassure the public of the water’s safety. The Bethpage Water District has repeatedly certified that the water is safe to drink once it reaches the tap.

But they’ve been met with a lot of skepticism, and health experts say that’s not unreasonable. The variety of contaminants in the plume and potential sources of exposure make it understandable that Bethpage residents ask questions. Drinking water standards continue to tighten as scientists learn more about chemicals’ long-term effects. How multiple contaminants interact and impact human health is poorly understood.

It’s very reasonable for the community to want some answers regarding what may be happening to their health.

Dr. Ken Spaeth, division chief of occupational and environmental medicine at Northwell Health and Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine

“It’s certainly among the most significant community exposures that I’ve seen,” said Dr. Ken Spaeth, division chief of occupational and environmental medicine at Northwell Health and Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine. “The combination, the range of different types of contaminants and the toxicological profile of many of them all add up to a very concerning situation.

“It’s very reasonable for the community to want some answers regarding what may be happening to their health.”

A suburb under a cloud

At the peak of Grumman’s operations, Bethpage brimmed with patriotism. The company built the Apollo Lunar Module. Equipment sits on the moon stamped “Made in Bethpage, New York.”

Grumman donated generously to the local Rotary Club and gave out turkeys at Christmas to employees. The roar of jet engine tests on Saturday mornings was a small price to pay — particularly when the company contributed up to $16 million a year in school property taxes.

Even without the company’s massive presence, Bethpage and surrounding hamlets served by the local water district convey a quiet American success story. They make up an archetypal suburb of 33,000 residents spread over leafy neighborhoods of single-family homes, neat lawns and strip malls dotted with pizza places, hair salons and dry cleaners. Broadway serves as Main Street for Bethpage, the unincorporated area within the Town of Oyster Bay.

Workers assemble Grumman Wildcats in Bethpage in October 1942. Photo credit: AP

Neighbors know each other, crime is low, schools are strong. The U.S. Department of Education honored Bethpage High School in September for academic excellence, one of three schools cited on Long Island.

Even the water was once a source of pride. At state fairs and Long Island malls, the Bethpage Water District won multiple blind taste tests against other water providers. A sign entering town once announced, “Welcome to Bethpage, Home of New York State’s Best Tasting Drinking Water.”

But tucked into the residential neighborhoods are visual markers of Bethpage’s problem.

At three water district well sites, metal “air stripping” towers that look like grain silos rise as high as 60 feet. Water from the plume trickles down over golf-ball-sized materials to disperse it into fine droplets, while air is forced upward to evaporate volatile organic compounds.

A Bethpage Water District treatment plant on Sophia Street. Photo credit: Newsday / Yeong-Ung Yang

The sites also include storage tanks holding 20,000 pounds of crushed carbon to absorb contamination — acting like giant Brita filters.

At the district’s Plant 6, where TCE contamination first closed a well in 1976, the water district has been constructing a $19.5 million building with an advanced system designed to remove 1,4-dioxane, a newly regulated contaminant once used to stabilize solvents like TCE.

Still, as far back as 1992, a Navy community relations plan reported that residents were concerned that contamination from the Navy and Grumman “may be a factor in the development of cancer.”

The report noted that, “As a result of their concerns, many residents who were interviewed stated that they were drinking and/or cooking with bottled water rather than municipal water from groundwater sources.”

‘What is it then?’

After two breast cancer diagnoses and uterine cancer, Maryann Levtchenko, 68, got genetic testing to see if she was predisposed to the diseases. She wasn’t.

“So maybe I do need to tell my story, because what is it then? It makes me question my whole life,” said Levtchenko, who is part of a pending 2016 class-action lawsuit against Northrop Grumman.

Levtchenko and her husband moved to Bethpage in 1975 and raised two kids, spending summers at Bethpage Community Park.

She adored the community and still does, she said from her living room, where she handed visitors bottled water.

“The unfortunate thing — I love it here,” Levtchenko said. “It’s a safe neighborhood, everybody knows one another. Everybody’s caring.”

She and her husband are retired, she said. But they stayed.

Deanna Gianni, left, Stephen Campagne and his sister, Pamela Carlucci, talk in January about Bethpage’s water and their concerns about health effects from Grumman pollution. Photo credit: Chris Ware

Still, Levtchenko believes something in the tap water, which she drank until only recent years, made her sick. She counts cases of multiple myeloma on her street and thinks about four parents of her son’s group of six friends who died of cancer when the kids were in school.

“It was like a Bethpage flare,” she said.

Cancer, a generic term for more than 100 separate diseases, is frightfully common across New York. One of every two men and one of every three women will likely be diagnosed with a cancer during their lifetimes, according to the state Department of Health. New York’s cancer rate is the fifth highest in the country, according to the state Department of Health.

Still, Bethpage residents feel that cancer cases are more prevalent here.

A few blocks away from Levtchenko, Pamela Carlucci, 68, a breast cancer survivor, took a photo of smiling neighbors off her refrigerator and started pointing.

“Cancer, cancer, cancer, cancer,” Carlucci said.

She and neighbors sat around her dining room table, counting at least 15 families with cancer among 29 nearby houses. Some of those households have seen numerous cases. For instance, Carlucci’s son, Philip, died of brain cancer at age 30 in 2007.

“It’s our own Love Canal,” Carlucci said, referring to the western New York neighborhood abandoned in the late 1970s after it was found to be inundated with industrial contamination.

“We all had gardens, my goodness. We grew eggplants, peppers, tomatoes, parsley,” said Deanna Gianni, 79, whose husband, Joseph, a mechanic, died of stomach cancer at age 74 in 2011.

Edward Mangano, the former Nassau County legislator and county executive who lives a mile and a half from Bethpage Community Park, remembers growing concerns about Grumman pollution in the 1980s and 1990s.

The issue hit home when his brother was diagnosed with multiple myeloma at age 36.

“Can you eat tomatoes you grow in the backyard? That was the number one question at every meeting,” said Mangano, who served as county executive from 2010 until 2017 and is appealing his 2019 conviction on federal corruption charges.

Homes are selling, but residents wonder if they’d get more if not for the pollution.

“I find it very difficult to show properties here,” Barbara Ciminera, a real estate broker, wrote in comments to the state about its latest cleanup plan. “People just don’t want to see anything here while this is going on.”

Real estate agents will sometimes ask Bethpage Water District representatives to stop by open houses to reassure prospective buyers.

“They’ll call the district and say, ‘We’re having an open house on Saturday. Do you think you can come by from 12 to 2 in case anyone has any questions?’” said district superintendent Michael Boufis.

I don’t think I know anybody that drinks water out of the tap.

Stephen Campagne, a Bethpage resident

Compounding residents’ fears is that the water’s taste, once a source of pride, has diminished, unrelated to the Grumman pollution.

In 2010, the state, citing bioterrorism concerns, removed the district’s waiver that allowed it not to use chlorine.

District tries to reassure

In the foyers of some homes, delivery jugs of bottled water still pile up.

“I don’t think I know anybody that drinks water out of the tap,” said Carlucci’s brother, Stephen Campagne, 65, a retired Con Edison worker who has lived in Bethpage since 1980.

Even the water district acknowledges that many residents haul cases of bottled water home.

“King Kullen, 3 for $9.99, they’re on every cart that walks out,” said district commissioner John Coumatos, a Bethpage restaurant owner.

At meetings, street fairs and festivals, the district repeats the mantra that it treats and tests plume water above drinking standards — and that tap water is more scrutinized than what is bottled.

“We try to tell the consumers the water’s fine. We fight it every day. Fight it every day,” Coumatos said.

John Coumatos, a Bethpage Water District commissioner, stands behind the quality of water that comes out of Bethpage taps. Photo credit: Newsday / Yeong-Ung Yang

It’s an uphill battle.

“Grumman’s caused that situation,” Coumatos said about the distrust of public water. Rebuilding trust will take time, he said. “You can’t pay enough money to take care of that.”

Bethpage Water District has just 12 full-time employees.

With that small staff, the district has had to fight for more aggressive cleanup while reassuring the public. And the list of concerns has only grown to include 1,4-dioxane as well as radium. The discovery of radium at elevated levels in 2012 led to the district shutting down one of its nine public supply wells.

Experts said the mounting disclosure of potential risk factors in Bethpage adds to the inclination for residents to connect cancers to pollution.

“A person who already believes that chemicals which have leached into our groundwater cause cancer is very prone to seek out and favor stories and information which confirm this belief,” said Dr. Curtis W. Reisinger, a clinical psychologist at Northwell Health.

Authors of the only state cancer study in Bethpage, which found in 2013 no evidence of higher rates, described their results as “scientifically appropriate and as informative as existing data will allow.”

Yet, Reisinger asked, “Are we so wrong to think the causes are environmental?”

“From a certain sense we can’t blame people for looking for external causes. And if you live on Long Island and you’re programmed pretty much cognitively, psychologically to look for causes other than genetics, it makes a lot of sense that — maybe it is the environment,” he said. “That’s what science is saying now, maybe the environment is responsible for a lot of this stuff.”

More than 1,000 current and former Bethpage-area residents have joined class action or personal injury suits about health effects from the pollution that stemmed from Grumman’s historic operations, lawyers said.

The Melville personal injury law firm Napoli Shkolnik represents most of those people, including Carlucci and Levtchenko, in the ongoing suits against Northrop Grumman, as well as the Town of Oyster Bay, which owns the Community Park property.

“My experience in environmental cases is that, fundamentally, not only the polluters — but the community politics — want to downplay the risks associated with any sort of contamination,” said Paul J. Napoli, a partner in the firm. “The polluters, because of liability, and the local politics because they don’t want to create hysteria.”

‘We’re tired’

At the former Grumman site on Grumman Road, about two dozen people came to a town community center last November to hear Navy representatives give an update on the cleanup, as required by federal law.

Bethpage resident Gina McGovern speaks at a public hearing on the state Department of Environmental Conservation’s $585 million groundwater cleanup plan in June 2019. Photo credit: John Roca

Northrop Grumman sent representatives to the meeting, according to the Navy, but they didn’t speak or publicly identify themselves. Northrop Grumman is mandated by the state to conduct its own public meetings about its cleanup.

The meeting, with bottled water provided upfront, quickly became a forum for residents to vent their frustration.

A dozen state and Navy officials and consultants sat off to one side, with the Navy’s highlighting ongoing cleanup initiatives and others they plan to start soon.

But the Navy’s project manager also affirmed that it would oppose the state’s more ambitious plan to fully stop the plume’s spread.

Instead, the manager, Brian Murray, said while some of the plume would continue to spread, under the Navy’s current plan it would concentrate on removing the highest toxic concentrations in the expectation the rest would naturally dilute, dissipate and break down.

Water district officials who have watched the plume spread for decades said the hope was illusory.

“Your solution to pollution is dilution,” said Teri Black, a real estate agent and Bethpage Water District commissioner. “I was glad I was sitting. It is unacceptable.”

Richard Catalano, 61, of Seaford, a human resources manager whose home sits above the plume, criticized the pace of action.

“It’s a disgrace what the Navy’s done!” he shouted.

Gina McGovern, a teacher and Bethpage resident, at one point interrupted: “I realize I’m talking out of turn and I apologize to all of you. But I’ve been sitting in these chairs for 20 years. I had to get babysitters when I first started. My youngest is out of college now. You know how much time in my life I spent sitting on these chairs, listening to the Navy discuss how they’re drilling holes?” she said.

David Sobolow, a volunteer co-chair of the Navy advisory board, noted Grumman’s absence among the presenters. “With all due respect, the Navy is the one that’s here trying to solve the problem.”

After the meeting, McGovern explained her anger. “The whole town is just — you can see the frustration level. We’re tired. We’re tired of trying to be nice. We’re tired of trying to be polite.”