Lone Bethpage cancer study leaves unanswered questions

Protesters greet people arriving at Bethpage High School for a state Department of Environmental Conservation meeting in June 2012 to discuss plans to clean groundwater at Bethpage Community Park. Photo credit: Newsday / Daniel Goodrich

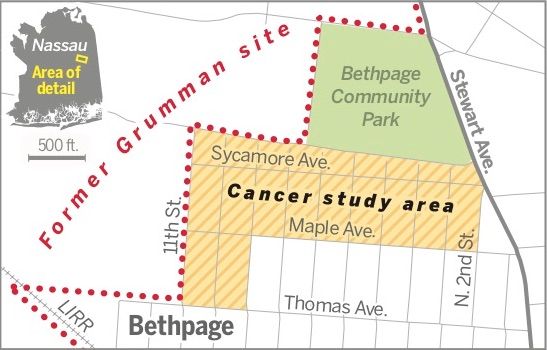

It was toxic soil vapor seeping into a handful of homes, not the massive groundwater plume emanating from the old Grumman property, that triggered Bethpage’s lone community cancer study.

After a three-year investigation, state health officials in 2013 found no higher overall cancer rates in a 20-block area closest to the former Grumman and Navy property, although they also noted the scientific limitations that make linking residential cancer clusters and pollution nearly impossible.

The cancer study did find that within a one-block area, all those diagnosed with cancer were younger than expected. But it concluded that even so, it was too small an area to provide a clear indication of an unusual pattern.

The debate over the strengths and weaknesses of the study — what to make of it and whether a more thorough investigation could have determined more — lingers in a community that for decades has believed it experiences a disproportionate share of cancer.

At its heart, the community is asking a seemingly simple question: Has the pollution in the water, soil and air caused illness there?

Answering that question through science is maddeningly elusive.

Calls for a study

The state has repeatedly counseled residents not to worry because all Bethpage drinking water is treated to government standards and is therefore safe to drink. Similarly, living over the underground water pollution “plume” hundreds of feet below poses no risk to the public, officials said.

Any study, however, that could support or debunk findings like the state’s confronts the scientific difficulty of tying an individual case of cancer to a specific source, an extreme rarity in almost any situation, experts said. Finding clusters of cancers is hard enough; linking those to a pollution source is rarer still.

The Bethpage study took form after the Navy in 2008 found vapors of the solvent trichloroethylene, or TCE, and two other chemical solvents in soil around its property, which Grumman operated. Further testing found contamination had reached a nearby neighborhood.

Credit: Newsday / Andrew Wong

The Navy installed air purification units at 14 homes, as well as a system to extract and contain soil vapors on its property.

Inside a handful of homes, the levels of the solvents were above state limits meant to protect human health.

By 2009, the clamor for a state cancer study had become intense. One resident provided a list of nearly 80 people diagnosed with cancer or lupus since the early 1960s. Community members made a map stuck with color-coded pins matched to different diagnoses and compiled a list of Bethpage High School graduates and parents stricken with cancer.

Edward Mangano, then a county legislator from Bethpage, and then-state Sen. Carl Marcellino asked the state to conduct a survey.

In April 2009, the state Department of Health’s Cancer Surveillance Program began evaluating cancer cases and possible environmental exposures. It relied on the state’s Cancer Registry — a database of all cases of cancer diagnosed or treated in New York State, tied to patients’ addresses.

No ‘unusual patterns’

The state released its finding of no higher overall rates in January 2013.

Using photographs of the community map and lists of cancer cases gathered by neighbors, the study found the citizens’ evidence inadequate.

Of the nearly 80 cases of cancer reported by residents, researchers could only confirm eight with the state’s database. Working off two photographs of the map, the study authors said that only “some of the names were visible.” A list attached with the map — provided by unnamed residents to the Navy, which passed it to the state — included streets and blocks where people had been diagnosed with cancer and were grouped by cancer type, but it did not include names.

“Much of the information that would have been useful for a more complete cancer evaluation was not available,” the state report said. “The information that was available did not indicate any unusual patterns of cancer.”

The state concluded other evidence was unpersuasive.

Five cases of breast cancer among 1979 and 1980 graduates of Bethpage High School were higher than the two cases that would be expected, for example. But the increase wasn’t statistically significant and could have been by chance, the study determined.

The information that was available did not indicate any unusual patterns of cancer.

Department of Health’s Cancer Surveillance Program report

But the state also decided to look at possible exposure to pollution in the area. Toxic vapor in homes justified taking an additional look at cancer rates, using the state’s database to drill down on specific areas, it determined.

In particular, researchers focused on blocks within the neighborhood known as the “Number Streets” that includes homes on 11th Street, where TCE and other chemical vapors had been found.

In the 19-block L-shaped area, south of Bethpage Community Park and east of the Navy-owned land, the study found 88 cases of invasive malignant cancers from 1976 to 2009.

But based on the average cancer rates in the state, outside of New York City, 107 cancer cases would have been predicted.

The report said, “uncertainties with population estimation may have led to an overestimate of the number of cases expected. Still, the calculations provide no evidence that the total number of cancers or the number of cases of any individual cancer was greater than expected in the study areas.”

The other area examined was a single block directly east of the former Navy site — between 11th and 10th streets, and Sycamore and Maple avenues — where chemical vapors had been found in or under six homes at levels above state standards.

In that block, six people were diagnosed with “invasive malignant” cancer between 1976 and 2009, including the types of cancers linked to chemicals found there . Still, the number was only slightly higher than the five that would have been predicted based on state averages, and not statistically significant, the report said.

The analysis found one concerning feature below the topline number: All those diagnosed with cancer were in their mid-20s to early 50s, younger than average for the different cancers.

“The number of cancers diagnosed in people under age 55 was greater than the number expected,” according to the report, which didn’t specify the statistically predictive number. “This difference was statistically significant, meaning that it was not likely to occur by chance.”

The report concluded that “due to the limited size of this one-block area, however, these results do not provide a clear indication of an unusual pattern of cancers.”

In a question-and-answer website released with the study, the state Department of Health said no follow-up was warranted.

‘They didn’t speak to anybody’

The results left many residents disappointed and frustrated that the state didn’t go beyond its database and knock on doors.

“They didn’t speak to anybody,” said Jeanne O’Connor, who co-founded a group that has collected 2,000 cancer cases in the hope of prompting another state study. She said the effort has become overwhelming, and the group has shifted its efforts to expanding awareness.

“They needed a bigger sampling area,” said Mangano, who later served as Nassau County executive from 2010 to 2017 and is appealing his 2019 conviction on federal corruption charges.

He said exposure went beyond the 20-block area studied and included people who were exposed for decades at Bethpage Community Park. Mangano had requested that the state examine a larger area.

The state, however, said larger areas, outside the blocks with the highest exposure levels, can often dilute results, making a cancer connection less likely. It also said its Cancer Registry is highly accurate, as certified by a national association of registries. And door-to-door surveys can be unreliable, with some residents unwilling to share information or unaware of previous residents’ diagnoses, according to the state.

The state Department of Health, like most federal and state agencies around the country that have attempted studies, has never tied a residential cancer cluster to chemical exposure in the environment.

Just three community cancer clusters nationally have been linked with environmental exposures such as water or air pollution, according to a 2012 paper that reviewed 567 cancer cluster investigations over the previous 20 years. They included cases of childhood leukemia in Woburn, Massachusetts, from TCE and childhood cancers in Toms River, New Jersey, from industrial pollution. Just one cancer cluster in a coastal South Carolina community with lung cancer and a history of work at a nearby shipyard with asbestos had been tied to a more definitive “established cause.”

Tough to draw a link

Part of the reason for the paucity is the difficulty of the science. Most cancers can’t be traced to a single specific cause. Additionally, cancer can take five to 40 years after exposure to develop, in which time people move and can be difficult to track. Influences such as age, race and lifestyle can affect cancer rates.

“Very often what we find is that while cancer levels are elevated, they’re not definitively linked,” said Brad Hutton, deputy commissioner for the state Department of Health, in an interview last year.

Critics say part of the problem is that state regulators tend to downplay risks and dangers in an effort not to alarm the public, but even they say studies can raise false expectations.

This type of study is not capable of demonstrating any cause-and-effect relationships.

2013 state cancer report

Dr. Howard Freed, who from 2008 to 2012 was director of the department’s Center for Environmental Health, said when there’s doubt the state minimizes risks in an effort not to cause a panic.

Freed headed the division responsible for the evaluation of the health effects of man-made chemicals.

In an email to Newsday, he wrote: “New York DOH has always emphasized scientific uncertainty over what many others see are clear warnings of real risk to the public,” adding, “Routine reassurance cannot be justified in the face of our profound scientific ignorance about the health effects of long-term exposure to toxins in drinking water.”

After reviewing the state’s Bethpage cancer study, Freed said the state appeared too quick to dismiss the community’s list of cancer cases and maps because of incomplete information, rather than trying to go back and get more data.

“It strikes me as not aggressive or a good-faith effort to try to substantiate people’s concerns,” he said in an interview. “If there’s information out there and they don’t seek it — to me it’s not effective.”

Yet Freed said another health study would be a “terrible idea.”

The state should “do what it can now to protect the public, and not wait for conclusive proof of harm, especially when such proof is unlikely to become available in the foreseeable future,” he said.

The state’s report itself laid out its limitations.

“This type of study is not capable of demonstrating any cause-and-effect relationships,” it stated. “At the current level of understanding, it is not possible to separate out all possible causes to determine the role of environmental factors in causing cancers in a small geographic area.”