Will Long Island Diners survive for the next generation?

Buffeted by changing tastes, increased costs and "cooler" competition, could diners eventually join the soda fountain and the automat in history?

Retired special education teacher Diane Sherman of Riverhead has spent much of her life going to diners. She grew up in Centereach, where back in the ’50s, the sleepy town only had a diner and a gas station. “It was a treat for us,” she said. “We’d always celebrate birthdays at the diner.”

When she was old enough to venture out on her own, it was almost always to a diner. As a young woman, Sherman sang in a wedding band, Sweet Ecstasy, and “if we were playing the South Shore, we’d always wind up at the [old] Oconee in Bay Shore at 2 in the morning for eggs and coffee.”

Now Sherman, 63, finds herself at Sunny’s Riverhead Diner & Grill four or five mornings a week, where she always takes the same seat at the end of the counter. “They see me walk in and they pour my coffee,” she said. “Look, I can make breakfast at home — I’m a pretty good cook. But I like connecting with my community, and that’s why I go to Sunny’s. Every town needs a diner.”

Once, pretty much every town on Long Island had a diner, but now, as they grapple with changing tastes, increased costs and competition from other restaurants, the question becomes: Are diners in danger of going the way of the soda fountain and the automat?

There are still about 100 diners in Nassau and Suffolk counties, one of the largest concentrations in the country according to diner expert Richard J.S. Gutman, but that’s about 40 fewer than there were in 1990, according to Newsday data. The two oldest (Sunny’s in Riverhead, built in 1932, and the Cutchogue Diner, 1941) retain the modest “dining car” style that characterized the prewar era, but most Long Island diners are sprawling structures built from the 1960s to the 1980s. The Island’s newest, the double-decker Landmark in Roslyn, opened in 2009, replacing the old Landmark built in 1964. While some have been renovated, not one new diner has been built on Long Island in the last 10 years, as far as Lou Tiglias, a partner at the Landmark, knows. The recent shuttering of such long-standing establishments as the Golden Dolphin in Huntington, Empress in East Meadow and the Corinthian in Central Islip, along with the teardowns of others to make room for banks and drugstores raises the specter of an industry in decline.

“We are in trouble,” Tiglias said, enumerating three major challenges diners are facing: Competition from trendy fast-casual restaurants, a labor shortage and increasing property values.

The classic diner

Whether clad in stainless steel, flagstone or stucco, diners hold a special place in the hearts of Long Islanders. More than places to eat, this is where toddlers get buckled into their first booster seats, teens congregate after sports practice, college kids on break return on their first night home and seniors on a budget rely on the early-bird special. And more than a few post-burial luncheons are held in the side dining room.

Watch Now: Feed Me TV

Where Have All the Diners Gone

Watch Now: Feed Me TV

Where Have All the Diners Gone

Long Islanders instinctively know what distinguishes diners from other restaurants, but defining them is a little trickier. Gutman, the author of “American Diner Then and Now” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), says a “true” diner is one that was prefabricated in a factory and moved to its location as a free-standing building. Luncheonettes and coffee shops were consciously copying the style of diners when they established themselves in locations that could not accommodate a diner — the middle of a village block, for example, or a strip mall.

For the diner customer and owners, though, its meaning comes from the experience it provides.

“Good food, good service — and they have everything,” is how Cynthia Compierchio of Medford summed up the diner experience. She grew up eating at the Peter Pan Diner, the fieldstone-clad diner tucked into the complicated interchange where Howells Road meets Sunrise Highway in Bay Shore, first with her parents and then while dating her future husband, Anthony. Now she and her 16-year-old son, Anthony, frequent the Metropolis Diner, a gleaming structure set among modest strip malls on Route 112 in Medford.

“Everything” is indeed what diner owners strive for. “You can get everything from an English muffin to a sirloin steak at any time of the day,” is how Peter Georgatos, co-owner of the Premier Diner in Commack, put it.

Covering all the bases at all hours requires an encyclopedic menu. Laminated and spiral bound, a typical diner menu clocks in at more than 200 items, including eggs, pancakes, waffles, hot and cold cereal, burgers, sandwiches (hot and cold, open-faced and closed), pasta and Parms, souvlaki and moussaka, steaks and chops and fish, ice cream and fountain drinks plus a colorful array of prominently displayed cakes and pastries. Portions are large, prices reasonable. The dining rooms are brightly lit with a variety of seating options — counter, tables and booths. Service is quick, servers wear uniforms and no one will give you a hard time if all you want is a cup of coffee.

Diners: A history

Contrary to common belief, diners did not get their start as retired railroad dining cars. Richard J.S. Gutman, author of “American Diner Then and Now,” who has spent a career dispelling this myth, explained that the original diners were simple lunch wagons pulled by horses. “They were the food trucks of the 19th century,” he said.

Eventually, the wagons evolved into semi-permanent structures that were produced by about a score of companies all over the country. Most of them have gone out of business, but not DeRaffele Manufacturing Co. in New Rochelle. Phil DeRaffele, the 91-year-old son of founder Angelo, estimates that his company has built more than 70 diners on Long Island.

Diner owners, often lacking the funds to buy real estate, would lease a piece of vacant land, dig a foundation, and then the manufacturer would slide the diner into position. (Over the years, many diner owners were able to purchase their properties; others continue to own the buildings but not the land they stand on.)

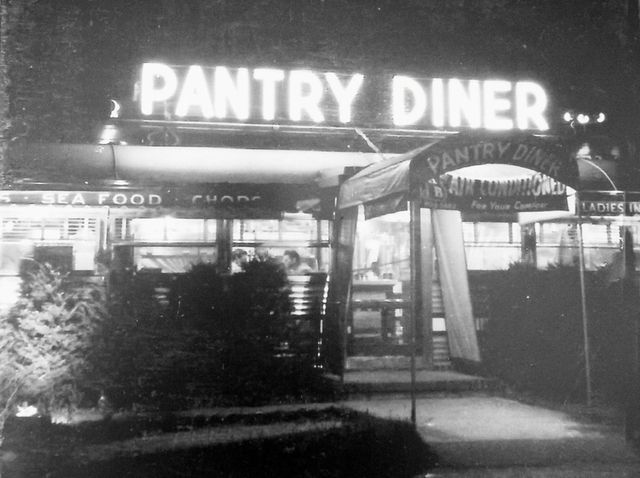

Originally manufacturers adapted the sleek look of railroad dining cars to their single-unit designs. Rockville Centre’s first Pantry Diner, a shiny stainless-steel box, was slid into position at the corner of Merrick and Long Beach Roads in 1949. In 1958, the original 40-seat unit was dragged away and owner Teddy Pagonis replaced it with a 90-seat unit. His daughter Jean Mavroudis recalled, “on the canopy it said ‘Good Food. Fine Service. Ladies invited.’ and I do remember women in mink stoles coming into the diner.”

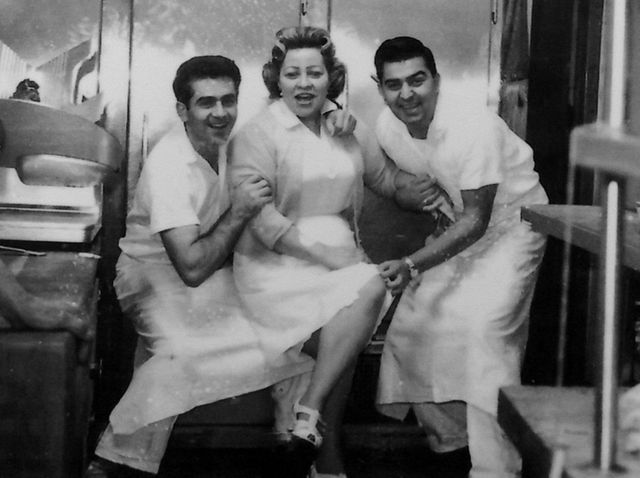

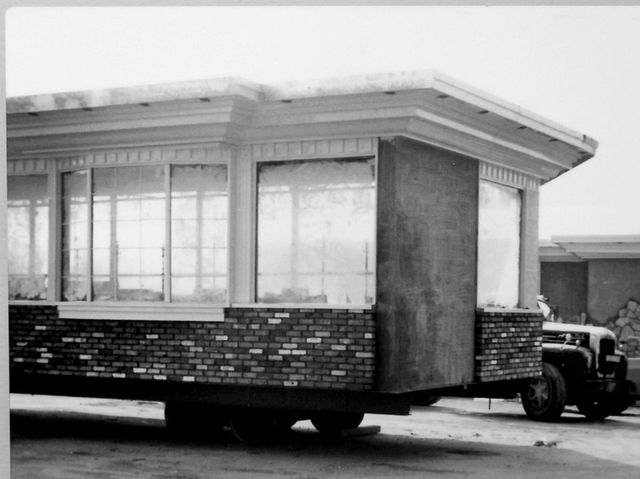

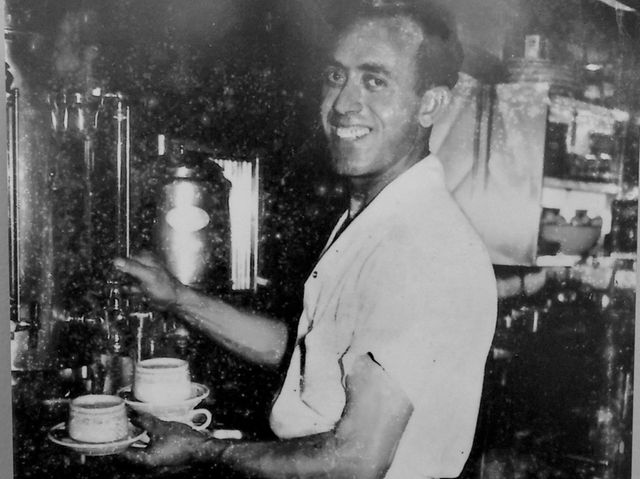

Clockwise: Pantry Diner in Rockville Centre; George Tsotsos (griddleman), Jeannie Coco (waitress) and Pete K. (soda fountain area) at Pantry Diner in 1968; Pantry Diner in 1973. It came in 7 sections which were then assembled on location; The ribbon cutting ceremony for the grand opening of the 1973 Pantry Diner; The original Pantry Diner; Teddy Pagonis, the original owner of Pantry Diner. Credit: Pantry Diner

In 1973, the 90-seater was hauled upstate and in its place DeRaffele erected a brick-and-stone structure that had been manufactured, in seven pieces, in New Rochelle. “It took about three months for them to assemble it,” Jean recalled.

Diner aficionados can date a diner from its style. After the war, DeRaffele pioneered the look of the new suburban diner. The Peter Pan in Bay Shore was an icon of this style: a multiunit structure accommodating 150 patrons that still had a stainless-steel exterior but much larger windows. (It has since been remodeled.) DeRaffele’s chief designer, Tom Ravo, said that as diners began to proliferate, some local governments objected to their flashy look. “They wanted diners whose style blended in more with the town.” Diner manufacturers responded with the “Mediterranean” style (red-tiled roofs, big arched windows, stone walls) and the “Colonial” style, whose brick walls, whites column and trim and coach lights suited small-town America.

Diner manufacturers helped many owners to finance their ventures. When the loan was paid, the owner could trade it in for a new model. Or he could expand, adding more units to the original one to form the huge diner with a big kitchen and multiple dining rooms. The diner manufacturers provided stylistic updates and so, with a little exterior work, the diner could evolve from stainless splendor to Colonial charm to Mediterranean magnificence to postmodern pizzazz.

The Greek connection

On Long Island, almost all diners are owned by Greek-Americans. Experts have debated the outsize role Greeks play in the local diner business. Author Richard Gutman, who lives in Boston and approaches his subject with a national perspective, said that in other parts of the country, Greeks are well represented among diner owners, but do not dominate. He also acknowledged that the New York metropolitan area is the country’s diner epicenter and one in which the Greeks are the major players. But there is no hard data on the phenomenon.

Modern challenges

Competition comes from all sides. “These new breakfast places — Maureen’s, Toast, Hatch — they are going after what’s most profitable in our business: Breakfast,” Tiglias said. At lunch and dinner, the diner must contend with any number of-the-moment fast-casual chains.

One arena in which diners used to be unchallenged was late-night/early morning food service. But this business has drastically decreased. “In the old days,” he said, “there was a ‘movie break’ around 11:30 p.m. and then another one, a ‘bar break’ after the bars closed, anywhere from 2 to 5 in the morning.” But Tiglias theorizes that DUI laws have curtailed Long Islanders’ desire to cruise around in the wee hours, and with the internet providing entertainment for the couch-bound, going out is no longer a necessity. These days, only a handful of Long Island’s diners remain open 24 hours.

Darren Tristano, CEO of CHD-Expert North America, a data-analysis firm that specializes in the food service industry, said that millennials and Generation Z are looking for contemporary experiences and are willing to pay more for them. Enter gastropubs and Instagram-worthy dessert bars.

Tiffany Salazar, a 28-year-old nurse from Lake Grove, and Raj Kumar, 30, a medical student from New Hyde Park, are frequent patrons of the Lake Grove Diner, but Salazar conceded that they’re in the minority among their peers when it comes to diners. Her friends think diners “are for old people,” she said, and prefer the food and the experience at a place like Chipotle.

Not only are fast-casual chains currently “cooler,” they are far less expensive to operate than diners. Food is often prepared in central commissaries so there’s no need for trained cooks on site, observed Tiglias. “It’s order-at-the-counter so they don’t have to pay waiters, it’s all served on paper plates so they don’t have to pay dishwashers,” he said.

These labor costs are at the heart of the diner’s struggle to survive.

“Our biggest challenge is we can’t find help,” said Georgatos, who has been working in diners since 1971. “The second generation–our children–don’t want to go into the business. And many of the young people find the work too hard. In the old days, someone would stop in once a week and ask if I have a job for them. That hasn’t happened in five years.”

Eleven miles due south of the Landmark, Tommy Mavroudis is preparing his Pantry Diner in Rockville Centre for the future. He is the grandson of the Pantry’s original owner, Teddy Pagonis, and is determined to continue the family’s legacy.

“I grew up here,” he said. “It was my grandparents’ and then my parents’ business. For the last 25 years I always thought about what I would do differently if I could.”

In 2011, he got his chance when the diner was destroyed in a fire. “My initial thought was to get the place open ASAP before my customers went somewhere else,” he said. But there were new building codes and other regulations and that slowed the process down. I realized that it was the perfect opportunity to build what I had been dreaming about.”

Mavroudis rethought the menu, the design and the service. It took seven years, but in 2018, the Pantry Diner reopened with a smaller menu and with a policy of no tips. (Customers rebelled, he said, and tips were reinstated after a few months.) The sleek décor features dark wood floors and tables, Edison light bulbs and instead of a counter, a bar.

”We don’t care whether they call it a diner or a restaurant,” said Patricia Francis, a frequent patron. “We still love it.”

In a changing real estate market, diners are caught on the horns of yet another dilemma: The land might bring in more money if it housed another type of business. “The footprint of the diner, it fits a more lucrative businesses,” said John Golfidis, a real estate agent for Realty Connect in Woodbury. The classic diner, he explained, is a free-standing building in a high-traffic area — the kind of location that also suits banks, drugstores and restaurant chains. Diner operators who lease their land (about 70 percent, according to Golfidis), may find themselves out of luck after their leases expire and their landlords seek to replace them with a large-chain or bank tenant.

For operators who own their land, an offer from that chain or bank can be tempting. That’s why the Jericho Diner is now a CVS, the Liberty Diner in Farmingdale is a TD Bank, the Merrick Townhouse is an HSBC, the Syosset House is a Panera and the East Bay Diner moved to Seaford from Bellmore, where it was replaced by a Red Robin.

Evolving to survive

In the end, each diner must find its own way to face the future. While diners such as the Landmark and the Pantry are trying major innovations, others are reworking the formula. Sheryl Morson and her husband, John Drakopoulos, sold the original Mitchell’s Diner in 2015 to a real estate developer who turned it into a Bank of America. But earlier this year they opened another Mitchell’s Diner, a block north of the old location. No longer a free-standing stainless-and-neon palace, it occupies the first floor of a modest office building and accommodates 58 patrons, as opposed to the old 168. But walk inside and it is unmistakably a diner.

Some diners are expanding service beyond their walls as home delivery apps such as GrubHub and DoorDash mean they can deliver food. All a diner needs to fulfill such orders are takeout containers, plasticware and plastic bags. Ronkonkoma-based Marathon Foodservice supplies most of the diners on Long Island, said Alex Kekatos, chief financial officer of the business his father founded. And he has seen a big increase in the amount of such paper products he is delivering to them. “In today’s market,” he said, “if you’re not delivering or you don’t have some type of to-go business, you’re missing out.”

In the last decade, the Landmark has upped its healthy-food game. “This diner has really healthy stuff,” said customer Jeanine Addario of Roslyn. “Huge salads, almond milk, soups that aren’t salty. They make French toast with egg whites and have a gluten-free menu.” That has made her a lunch regular.

At the Premier Diner in Commack, Georgatos and his wife, Helen, have made quality food their calling card. “We make our own gravies from our own stock,” he said, plus bread and pancake batter. A veteran of the Hunts Point produce market, he is bullish on vegetables, opting for super select cucumbers and Sunkist 140 lemons. Still, Georgatos has long-term doubts. “I don’t give diners too long — maybe 20 years,” he said.

Left: Waitress Brittney Lynch serves diners at the Premier Diner in Commack on Nov. 14, 2018. (Photo credit: Thomas A. Ferrara) Top: Greek salad with chicken is served at the Premier Diner in Commack. (Photo credit: Thomas A. Ferrara) Bottom: Pumpkin-pecan pancakes topped with powdered sugar and a side of cinnamon dusted whipped cream at the Premier Diner. (Photo credit: Daniel Brennan)

It’s a sobering vision of the future and, for many Long Islanders, an inconceivable one. Who wants breakfast choices dictated by fast food chains? Who wants to drive along Sunrise Highway in the wee hours, searching in vain for a stack of pancakes?

Riverhead’s Diane Sherman had a hard time imagining how she’d start her day if Sunny’s weren’t there. “I suppose I could stop at the local bagel shop,” she said, “but it’s not the same. It’s just not that feeling of family.”

Diner expert Gutman is not worried. “I’ve been hearing for 50 years that the diner is in decline,” he said, “but it’s the nature of the business that individual diners come and go. The institution of the diner has been here for well over a century and it has changed to keep up with what people like to eat. There is no way the diner will disappear.”

Credits

Reporters: Erica Marcus, Tory N. Parrish, Lisa Irizarry | Editors: Alison Bernicker, Jessica Damiano, Marjorie Robins, Shawna VanNess, Jeffrey Williams | Photo editor: Hillary Raskin | Research: Dorothy Levin | Design: Anthony Carrozzo, Seth Mates